Abstract

Purpose of Review

To identify factors associated with obesity in veterans of the recent, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) war conflicts.

Recent Findings

Over 44% OEF/OIF/OND veterans are obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2), which exceeds the national obesity prevalence rate of 39% in people younger than 45. Obesity increases morbidity, risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D), and mortality as well as decreases quality of life. A scoping review method was used to identify factors associated with obesity in young veterans. Military exposures, such as multiple deployments and exposure to combat, contribute to challenges in re-integration to civilian life in all veterans. Factors that contribute to increased risk for obesity include changes in eating patterns/eating disorders, changes in physical activity, physical disability, and psychological comorbidity. These conditions can contribute to a rapid weight gain trajectory, changes in metabolism, and obesity.

Summary

Young veterans face considerable challenges related to obesity risk. Further research is needed to better understand young veterans’ experiences and health needs in order to adapt or expand existing programs and improve access, engagement, and metabolic outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Obesity, Young veterans, OEF/OIF/OND, Mental health, Transition to civilian life

Introduction

Since the terrorist attacks of 9/11/2001, our all-volunteer military service members have experienced the longest mobilization of troops to theaters of war in recent history. These conflicts encompassed three major military eras: (1) Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), the US military’s operation in Afghanistan between October 2001 and December 2014; (2) Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) the conflict in Iraq between March 2003 and August 2010; and (3) Operation New Dawn (OND), the shift in US military engagement into an advisory and rebuilding role, officially ending in December 2011 [1]. Over 2.7 million men and women have served during these war conflicts—with over 5.4 million individual deployments [2]—and over 1.2 million users of the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) healthcare system [3].

The impact of military experience on human health and behavior can be profound. Serving in the military, deploying to overseas missions, participating in combat operations, sustaining trauma and/or serious physical and/or mental injuries, and ultimately reintegrating back into civilian life can contribute to a host of health burdens that often persist for a lifetime [4–7]. Due to the severity and ongoing nature of the OEF/OIF/OND conflicts, over 75% of enlisted service members experienced multiple deployments to combat zones, with over 40,000 troops having spent more than 36 months of service time in war [8]. More time spent in combat zones increases the likelihood of suffering a debilitating impact on both physical and mental health [4, 9].

According to the 2017 VHA healthcare utilization report, the top three medical concerns for enrolled OEF/OIF/OND veterans are (1) Diseases of Musculoskeletal System Connective Tissue (62.3%), (2) Symptoms, Signs and Ill-Defined Conditions (58.7%), (3) Mental Disorders (58.1%), and (4) Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases (39%) [3]. Obesity in the OEF/OIF/OND veteran cohort is another growing source of concern for the VHA [10–14]. Current prevalence of obesity [body mass index (BMI) of over 30] in OEF/OIF/OND veterans is estimated at 42.1–44% [13, 14]. Prevalence of overweight and obesity is 75–84% in this cohort [12, 15]. These high rates of obesity at a young age are cause for considerable concern, as obesity is associated with numerous health risks such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease, and reduced quality of life [16]. According to 2013–2014 statistics, approximately 4.8% of veterans between age 22–44 are diagnosed with T2D [17], but prevalence of T2D is expected to rise as this young veteran cohort ages. Therefore, prevention and management of obesity in OEF/OIF/OND veterans are critically important.

Obesity—and its associated health consequences—is a result of a complex interaction between individual, social, and environmental factors. For example, comorbid mental health conditions—especially post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression—have been linked to obesity in both civilian [18] and veteran populations [19, 20]. Deployment stress, exposure to combat, sustaining injuries, and trauma—unique characteristics of military service—are often antecedents of mental health conditions, which subsequently can increase risk for obesity. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to review the literature on factors associated with obesity in veterans of recent war conflicts and discuss strategies that can help mitigate further burden of obesity as well as the prevention of T2D in younger veterans.

Design

A scoping review of the literature was used as it allows for the inclusion of studies of different methodologies, purposive and systematic sampling, and rigorous data reduction and display to synthesize results [21, 22] .The process included (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies by an iterative literature search and the assistance of the medical librarian; (3) selecting studies that met inclusion criteria; (4) charting the data by systematically extracting and organizing data in tables; (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results; and (6) identifying conclusions and clinical and research implications. We followed the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [23].

Methods

Our research question was what are the factors associated with obesity in OEF/OIF/OND veterans? An iterative and strategic computerized search was conducted on four scientific databases (Ovid Medline and EMBASE, CINAHL and PsychINFO) from October 2001 to April 2019, spanning the years of the OEF/OIF/OND conflicts. Search terms included veterans, obesity, post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD, depression, anxiety, TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury), MST (Military Sexual Trauma), eating disorders, binge eating, deployment and Iraq and Afghanistan. We used purposive sampling to provide an overview of the factors associated with obesity studied in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Once factors were identified, we conducted systematic searches to identify all relevant studies. We also handsearched reference lists. Inclusion criteria were (1) sample of OIF/OEF/OND veterans (both men and women), (2) conditions, symptoms, or experiences associated with obesity, (3) study results available as full text, (4) and written in English. Studies that did not discuss obesity, reported on older veteran cohorts or on ex-military members from other countries, were excluded.

Articles were extracted and combined into an online reference management software, EndNote [24]. Duplicate copies were removed. One author read the titles and abstracts of each article, excluded ineligible papers, and identified relevant studies for full text review. This was cross-checked by another author. A total of 24 articles included data on factors associated with obesity, and pertinent data was extracted that included author, date of publication, study purpose and design, sample characteristics, study characteristics, outcomes, and main findings related to obesity. Studies were organized by each factor in order to compare and synthesize results.

Results

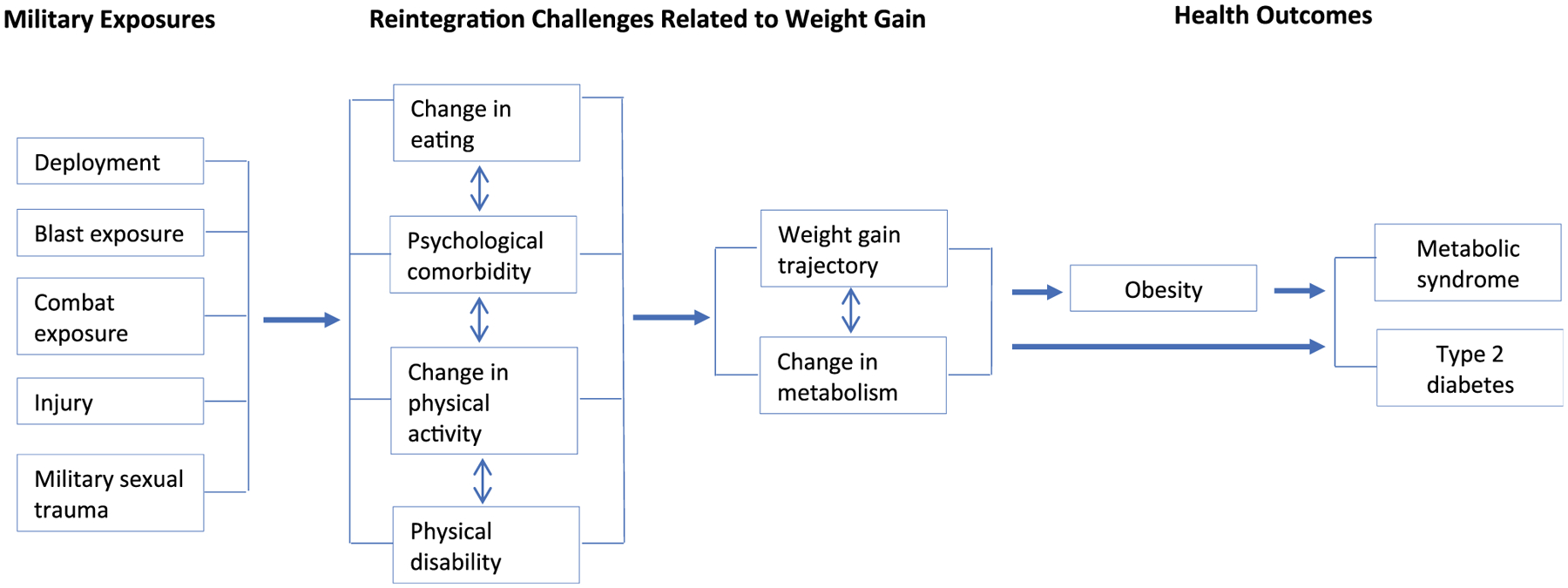

Factors associated with obesity in OEF/OIF/OND veterans resultant from military exposures are identified in Fig. 1. Military exposures [e.g., number of deployments, blast and combat exposure, injury, and military sexual trauma (MST)] are factors that influence health and re-integration to civilian life. Re-integration challenges that can contribute to rapid weight gain and changes in glucose metabolism include changes in eating patterns/eating disorders, pscyhological comordities, changes in physical activity, and physical disabilty [25]. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and T2D are serious sequelae that can then occur in young veterans. These factors will be discussed in more detail.

Fig. 1.

Factors associated with obesity in young veterans

Military Exposures

Multiple deployments to international conflicts increase deployment stress in service members and the likelihood of exposure to combat and military blasts, which can lead to injury (such as a TBI) as well as increased risk for the development of psychological sequelae (PTSD and depression in particular) and physical disability [5]. Although high casualty was observed on the OEF/OIF/OND military fronts, more service members survived compared to previous wars and higher numbers returned to civilian life wounded [26].

Trauma during military service can also stem from non-combat-related events—such as MST. In recent research, MST has been shown to negatively impact adjustment to civilian life and eating [27], as well as increase the incidence of obesity [28, 29]. In a 2016 meta-analysis, the prevalence of MSTwas estimated at 15.7% in all veterans [30]. In 2010 data, MST was found to be 15.8% in a sample of OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 125,729) [31], but by 2017, another retrospective data analysis on this veteran cohort (n = 595,525) reported the prevalence of MST (as diagnosed in VHA medical record) to be as high as 31% [32]. Gender differences were reported in a nationally representative cohort of OEF/OIF/OND veterans with young women veterans experiencing more MST than men (14% vs. 1%) [28]. Having a positive screen for MST increased the odds of being obese by close to 30% in women [OR 1.29 (1.23–1.36)], and by 13% in men in this national cohort of veterans [OR = 1.13 (1.08–1.19)] [33]. Female veterans diagnosed with MST were also more likely to be obese versus those without MST in two studies conducted on OEF/OIF/OND veterans [29, 34]. While the link between MST and obesity has not been fully determined, psychological sequelae such as eating disorders or PTSD may be contributing factors.

Changes in Eating Patterns and Eating Disorders

Continuation of unhealthy eating habits developed in active duty (e.g., intaking large amounts of food) may also continue upon reintegrating into civilian life; however, there is limited research in young veterans with respect to eating patterns and obesity. Eating disorders (ED), which include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder (BED) [35], have been examined in relation to obesity in young veterans [36]. In a longitudinal analysis in OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 595,012), the prevalence of BED—as measured by ICD-9 medical diagnosis—increased from 0.1% in the first year after leaving the military, to 0.2% after 5 years of discharging from service [32]. Another in a cross-sectional analysis of returning OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 332), 8.4% met BED criteria as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire [37].

Gender differences in ED have also been evaluated [32]. In one study (n = 662), a BED diagnosis was documented in 1.2% of women and 0.4% in men, but interestingly, 18.6% of women and 7.9% of men self-reported an eating disorder, indicating that ED may be an underdiagnosed conditions in OEF/OIF/OND veterans contributing to obesity [32].

Although scientific debate behind the emotional regulatory drive of ED continues, it is suggested that mental health comorbidities play a role in the development of ED, which have been associated with obesity [36]. According to one analysis in OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 332), the odds of a BED diagnosis was increased in those with PTSD [OR = 3.37 (1.34–8.46)] [38], as well as in those with elevated depressive symptoms [OR = 7.53 (2.69–21.04)] [37]. In another study (n = 593,739) of young veterans, having one mental health condition (such as PTSD or depression) increased the odds of ED by over 11 times [39]. Lastly, OEF/OIF/OND veterans with ED were also most likely to have PTSD as documented in their medical chart (46.3% of women with PTSD vs. 23.3% of women without PTSD; 40% of men with PTSD vs. 29.7% of men without PTSD) [32]. A positive screen for MST also doubled the risk of ED diagnosis (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) year 1 = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.64–2.50; year 5 AOR = 1.90, 95% CI = 1.53–2.36) [32] further indicating the impact on trauma and mental health on the development of ED. Lastly, young veterans with a BMI over 30 reported greater emotional eating when stressed [40], providing further evidence of the link between mental health conditions and obesity in young veterans.

Psychological Conditions

Mental health conditions, such as PTSD and depressive disorders, are common in OEF/OIF/OND veterans and have been associated with increased risk for obesity. Over 58% of OEF/OIF/OND veterans using the VHA system in 2015 sought mental health treatment, of which, 32% were treated for PTSD and 26% were treated for depressive disorders [3]. Other mental health conditions that occur in veterans include anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and substance use disorder [12].

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PTSD is a mental health condition that may result from trauma due to deployment stressors, combat exposure, or MST [19, 20, 41, 42]. In particular, those who served in the Army and Marine branches of the military, and who were exposed to frequent deployments, combat operations and lengthier service times in war zones have been found to be at higher risk for PTSD [4].

A 2015 meta-analysis on PTSD in OEF/OIF/OND veterans reported a prevalence between 5.8–41.3%, with an estimated cumulative average rate of 23.1% (∓8.4 %) across all VAs [43]. PTSD prevalence rates in OEF/OIF/OND veterans demonstrated a steady increase in recent years (2.1%/year) [43]. Gender differences in PTSD diagnosis in OEF/OIF/OND veterans have been reported with a higher prevalence of the condition in men (15 [16]–38.4% [12] compared to 11 [16]–30.8% in women [12]). A higher prevalence of PTSD in racial/ethnic minorities compared to Caucasians has also been reported [15, 28].

While the prevalence of obesity within OEF/OIF/OND veterans diagnosed with PTSD has ranged between 11.5 and 12.5% [14, 44], young OEF/OIF/OND veterans affected by PTSD consistently stay in the highest risk group for higher BMI [10, 12, 41]. A significant association between PTSD and obesity was demonstrated in a case-control study comparing combat experienced OEF/OIF/OND veterans with or without PTSD [45••]. This was corroborated in a longitudinal analysis concluding that new onset and chronic/persistent PTSD significantly increased the odds of rapid weight gain (> 10% over 6 years) in veterans compared to those without PTSD [46]. Authors of this study suggested underlying neuroendocrine and autonomic nervous system dysregulation, eating disorders, comorbid substance abuse, and adjuvant pharmacotherapy as possible mechanisms of action leading to excessive weight gain [14, 46].

Research on gender differences in the PTSD-obesity risk association has been conflicting. In one study, the prevalence of obesity in OEF/OIF/OND veterans with PTSD was 25.5% in women and 35.4% in men, after adjusting for demographic and military exposures such as combat experience [12]. In other studies, a higher proportion of women veterans with PTSD were obese compared to men (42% vs. 32%) [29] and (16.9% vs. 12.5%) [44].

Depressive Symptoms and Disorders

The prevalence of moderate to severe depressive symptoms in OEF/OIF/OND veterans has been reported to be approximately 26% in those who utilize the VHA health care system [47]. Per VHA healthcare utilization reports, risk factors for depressive disorders (as identified from diagnostic coding in medical chart review) from military service has been attributed to the stressors of combat and deployment as well as to MST [48]. Gender differences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans with depressive disorders have been reported. In a retrospective chart review of OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 792,663), a depression diagnosis was reported in 30.4% of women and 22.9% in men [49]. In a smaller sample of Connecticut OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 1129), a depression diagnosis was reported in 48% of women versus 39% of men [28]. In a more recent analysis of OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 267,305), smaller but still different rates of diagnosed depressive disorders in women (15.1%) versus 10.8% of men were reported [16].

Depression has been reported to be a risk factor for obesity in both civilian [50] and veteran research [10, 12, 28]. This has been confirmed in OEF/OIF/OND veterans with higher rates of depressive disorders who are obese compared to those with normal body weight (15.5% vs. 10.3%) [14]. In addition, young veterans with increased depressive symptoms had a clinically significant weight gain (≥ 10% of body weight gain) at higher rates than those without depressive symptoms [51].

Similar to the research on obesity and PTSD, gender differences in the depression-obesity association have been reported to affect women more than men. In a retrospective analysis (n = 496,722), depression was positively associated with increased weight gain in female veterans but not in men [12]. This was echoed by another analysis of OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 267,305), showing increased risk for obesity in women veterans with depression versus men with depression (HR = 1.17 [1.09–1.27] in women vs. 1.01 [0.95–1.08] in men) [16].

Other Mental Health Conditions

Other mental health conditions in young veterans include anxiety disorders, alcohol use disorder, substance abuse, and suicidal ideations. In a sample of OEF/OIF veterans (n = 303,223), the prevalence of diagnosed PTSD was 24%, depression 53%, anxiety disorder 29%, adjustment disorder 26%, alcohol use disorder 22%, and substance abuse 10%, indicating the range of mental health challenges in this population [44]. After adjustment for covariates including tobacco use, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, veterans with a mental health diagnosis had signficantly higher rates of obesity [44]. These results were confirmed in a subsequent study (n = 496,722), with those with mental health conditions more likely to belong to higher BMI risk groups after adjusting for covariates, including anti-psychotic medications [12]. Lastly, mean BMI in young veterans with comorbid suicidal ideations and PTSD (n = 130) was 29.50 (SD 4.87), with BMI moderating the association between PTSD symptoms and SI [52].

Changes in Physical Activity

While research on the physical activity of young veterans during re-integration to civilian life is limited, the high levels of physical activity and endurance training in military life is unlikely to continue after active duty. In one study, only 59% of a sample of OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 266) met physical activity recommendations (> 150 min/week moderate-to-vigorous exercise) [53], and 28.6% did not engage in exercise at all [54]. Depression and somatic symptom severity were correlated with decreasing odds of meeting weekly recommended exercise [54].

Physical Disability

Physical disability as a result of combat exposure is another possible contributing factor to obesity in young veterans. Approximately 70–77% of combat-related wounds were sustained from explosive blasts during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars [38, 55]. According to one report, almost half of army soldiers experienced multiple explosive blasts within 10 m of distance (about 33 ft), which could impair brain cells over time even without immediate loss of consciousness [56]. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the most common outcome of these injuries, and a leading cause of impairments, disability, and death amongst Iraqi and Afghanistan veterans [57, 58].

Research on the relationship between physical disability and obesity in young veterans is limited and confounded by other comorbities. In a sample of OEF/OIF/OND veterans with TBI (n = 450), comorbid PTSD was present in 80% of the sample [59]. Mean BMI was 28.39 (SD 4.62), indicating the high likelihood of being overweight or obese when suffering from TBI and PTSD. Chronic pain and PTSD have also been studied in OEF/OIF/OND veterans with respect to obesity, as chronic pain prevalence is over 40% in returning OEF/OIF/OND veterans [60]. In one study (n = 5,242), comorbid PTSD was more prevalent in those who reported persistent pain (33.6% vs 6% in those with no pain), and similarly, comorbid obesity was more prevalent in those with persistent pain (48.8% with pain were obese, vs. 37.9% w/o pain) [61, 62]. Additional data shows that those with comorbid PTSD have higher pain severity and disability and than those without PTSD [63]. Thus, physical disabilities in combination with PTSD increase risk for obesity [46, 64••].

Reintegration and Weight Gain Trajectories

Concerning weight gain trajectories on recently discharged OEF/OIF/OND veterans have been reported as veterans reintegrate into civilian life. In a large prospective study (n = 38,686), veterans gained twice as much weight compared to active service members (1.2–1.3 kg/year vs. 0.6 kg/year) during the first 3 years of separating from the military [51]. Similar trends in weight gain trajectories were observed in an even larger sample of recently discharged OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 496,722) using latent class trajectory analysis and identifying weight gain clusters [12]. In a third study following OEF/OIF/OND veterans (n = 42,200) over 6 years post-military discharge, a mean weight increase of 4.1 kg was reported [14]. These trends are especially of concern, as annual weight gain trajectories reported in the general population resemble more of those seen in active military personnel (0.55 kg/year for men; and 0.52 kg/year for women [65].

While research on young veterans has consistently demon strated that men have a higher risk for overweight or obesity compared to women [16], and male veterans in general enter the VHA system with higher BMIs then women [15], OEF/OIF/OND women veterans demonstrate a higher risk for clinically significant weight gain after completion of active military service. In a study conducted in 2011, female veterans experienced a steeper increase in BMIs over 6 years compared to men (annual BMI change of 0.5 to 4.8 kg in women vs. 0.7 to 2.8 kg in men) [15]. This was confirmed with 2013 data, also showing that the mean weight increase in female veterans was + 6.3 kg vs. + 5.7 kg in men within 6 years of separation from the military [51].

Older age, minority race/ethnicity, less education, higher BMI at the time of discharge from service, and having deployment experience with combat exposure were additional risk factors for rapid weight gain upon transition back to civilian life [15]. Comorbid mental health diagnosis also was associated with a weight gain trajectory during adjustment to civilian life [46, 64••].

Physiologic Changes in Metabolism

Metabolic risks of obesity have been studied in OEF/OIF/OND combat veterans with and without PTSD [n = 166, 100% men, mean duration of PTSD diagnosis 5.9 years (SD = 2.3)] [45••]. The impact of PTSD on endocrine system pathology was evaluated and measured with the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), a method for evaluating β-cell function and IR via fasting glucose [66]. Veterans with PTSD had significantly higher BMI (mean = 29.9 [SD 5.0] kg/m2) than those without PTSD (mean BMI = 28.4 [SD 4.8]; p = 0.04) [45••]. Of this sample, 47% of veterans with PTSD had abnormal IR (HOMA-IR > 3) compared to 25% of controls (no PTSD). This variance was further pronounced in those with HOMA-IR > 5, where 28% of cases compared to 10% of controls had abnormal IR levels [45••]. Proinflammatory biomarkers were all higher in cases versus controls showcasing a cascade of complex pathological impact and inflammatory reactions in those with PTSD, which prior research indicates to be driving mechanisms to obesity risk and development [45••].

Finally, three recent studies evaluated the association between PTSD and the development of metabolic syndrome (MetS) referring to the presence of 3 out of 6 conditions of (1) central obesity, (2) dyslipidemia, (3) hypertension, (4) IR and glucose intolerance (GI), (5) proinflammatory state, and (6) prothrombotic state in OEF/OIF/OND veterans [67]. There was a higher prevalence of MetS amongst young veterans with PTSD compared to veterans without PTSD (21.3% vs. 13%, respectively) [45••], (33.6% vs. 23.1%) [68], and (as high as 36.6% of the cases vs. 26.3% in those without PTSD) [69]. Thus, these findings establish that PTSD is a risk factor for the development of MetS, a comorbid condition with obesity.

Discussion

High rates of overweight and obesity are seen in young veterans increasing their risk for T2D and other obesity-related complications. Factors associated with obesity in OEF/OIF/OND veterans are complex and interrelated, but the evidence outlined in this scoping review suggest future chronic disease incidence and burden will increase as this cohort ages.

Predisposing military exposures and the high prevalence of mental health conditions—particularly PTSD and depression—increase the risk for weight gain and obesity in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. The VHA is fully committed to provide screening and evidence-based treatment modalities for mental health conditions delivered via a holistic healthcare model and innovative modalities to all veterans, including young veterans [70]. While numerous mental health resources are available for veterans, including newer initiatives using positive psychology (Table 1), efforts to assure access and expansion of services for young veterans is needed. More studies are needed that examine the benefits of mental health treatment programs on BMI and physical health (e.g., metabolic syndrome), beyond veterans treated with anti-psychotic medications [71]. Research on the prevention and treatment of MST is also needed.

Table 1.

Mental health resources of veteran health administration

| Organization | Resources |

|---|---|

| Mental Health Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (MH-QUERI) | Identify gaps in mental health care delivery and interventions to address them Support and enhance the implementation of evidence-based practices—and promising clinical practices that address mental health conditions in veterans |

| Defense Centers of Excellence (DCoE) for Psychological Health Resource Center (health.mil) | Principal integrator and authority on psychological health and traumatic brain injury knowledge and standards for Defense Department Maintains 24/7 outreach center to provide psychological health information, resources, and referrals for service members, veterans, and their families |

| National Center for PTSD (PTSD.va.gov) | Research and educational center of excellence on PTSD for veterans and clinicians Provides links to mobile apps on PTSD, mindfulness, problem drinking, anger management, smoking cessation, and moods |

| Veteran Training (Veterantraining.va.gov) | Online anonymous programs on overcoming stressful problems, anger and irritability management, veteran parenting, and sleep |

| Mental Health website (mentalhealth.va.gov) | Resources on depression, traumatic brain injury, military sexual trauma, substance use, suicide prevention, and other conditions |

| National Center for Telehealth and Mobile Health Technology (t2health.dcoe.mil) | Afterdeployment.org—website for self-care solutions to psychological health in veterans. Core project of DCoE for Psychological Health Resource Center |

| Team Red, White & Blue (teamrwb.org) | A community-based non-profit program to develop positive social networks and enhance enrichment outcomes in veterans. Builds leadership and social resilience through strength-based activities. Promotes physical activity, community involvement, and social activities with civilians and veterans with civilians and veterans |

Because mental health conditions impact the behavior and physical health of veterans, greater focus on incorporating and combining these services with obesity prevention within primary care may be needed. In 2007, the VHA established the Primary Care-Mental Health Integration (PCMHI) program, and studies involving veterans and providers have found the program to be a practical approach to improving screening and health outcomes [72]. Ongoing strategies to assess implementation and provider adherence, provide reliable leadership guidance, determine global payment structures, and overcome barriers to integration are needed [72, 73].

Innovative programs, such as the treatment of PTSD with a physical activity program, are also promising approaches to improve both mental health and BMI [74, 75]. Other innovative weight management programs in the VHA have incorporated mental health (such as cognitive behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based stress reduction and weight management) [76]. However, wide-spread implementation of these programs is needed.

The VHA offers several evidence-based programs for weight management (MOVE!) and diabetes prevention (VA-DPP) to all veterans nationally, which have demonstrated significant weight loss in veterans of all ages at 12-month follow-up (Table 2) [77, 78]. However, suboptimal utilization of this valuable resource amongst OEF/OIF/OND veterans has been reported [79]. In one study (n = 24,899), only 4% of eligible young veterans referred to the MOVE! Program completed the recommended 12 visits/year [80]. Moderators of poor attendance included gender (male), a PTSD or depression diagnosis, comorbid pain, and higher baseline BMI [80]. More recently, a TELEMOVE program has been evaluated with promising results in veterans of all ages [81, 82]. Challenges in attendance and implementation of this program have also been reported [82, 83]. Use of mHealth tools may be another strategy for reaching young veterans with obesity prevention and treatment programs. Currently, the VHA offers mHealth tools addressing mental health, parenting for young veterans, and most recently weight management that allow for anonymous and remote access to care (Tables 1 and 2) [84]. Evaluation of mHealth programs in young veterans is needed to improve access, acceptability, and engagement—all factors that contribute to improved outcomes.

Table 2.

Obesity prevention or treatment resources of Veterans Health Organization

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| MOVE! | National VA weight-management program that focuses on health and wellness, healthy eating, and behavior change. Sixteen group-based sessions at VA site for all overweight/obese veterans |

| TeleMOVE | Remote program developed from MOVE!—daily interaction with in-home messaging to receive content and health professional support |

| MOVE!11 | An 11-item questionnaire to generate an individualized report for self-study or use with primary health provider |

| MOVE!Coach | A 19-week self-guided program via mHealth that covers content in the MOVE! Program |

| Veterans Affairs Diabetes Prevention Program (VA-DPP) | A group-based diabetes prevention program provided for veterans at VA sites |

Lastly, the VHA is known for its comprehensive electronic medical record (EMR) system [85, 86]. Currently, there is a feature that alerts clinicians of recent combat veteran status to prompt early diagnosis and treatment of health conditions. More consistent use of clinical decision support within EMRs can also improve the assessment and management of obesity in clinical settings (e.g., follow-up for referrals to MOVE! Program). Behavioral support could also be provided through the VHA online platform for communication between patients and providers.

There are several limitations to acknowledge in this scoping review. Additional obesity risk factors, such as sleep disorders that may contribute to weight gain and obesity in the general population and older veterans, have not been discussed. In our search on obesity-relevant articles in OEF/OIF/OND veterans, we did not locate any publications on these topics; however, research may have been presented within the context of a study not focused on obesity. Few longitudinal studies have been conducted, limiting our understanding of the mechanisms of risk. Finally, some risk factors for obesity, such as depression and eating disorders, used different measurements (e.g., ICD-9 code or self-report), sample sizes varied, as did the sampling source (e.g., all veterans in this cohort vs. all veterans in this cohort accessing mental health services).

Conclusion

Young veterans face considerable challenges related to obesity risk due to their military service, high prevalence of comorbid mental health conditions, and the stressors of returning to civilian life. We recognize that there are immensely valuable skills and ethos learned during military service that could be incorporated into health promotion programs. Each veteran cohort presents unique strengths and challenges that need to guide health care efforts. Further research on young veterans to better understand their experiences is needed to adapt existing programs, expand effective programs, and develop innovative strategies to improve access, engagement, and health outcomes and reduce risk for metabolic disorders and T2D.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

•• Of major importance

- 1.Dates and Names of Conflicts - Veterans Employment Toolkit. 2015; [updated 20150824. Available from: https://www.va.gov/vetsinworkplace/docs/em_datesNames.asp. Accessed 14 Jun 2019.

- 2.Wenger JW, Wenger JW, O’Connell C, O’Connell C, Cottrell L, Cottrell L. Examination of Recent Deployment Experience Across the Services and Components. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2018. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1928.html. Accessed 9 Jun 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. VA Health Care Utilization by Recent Veterans - Public Health. 2019; [updated 20190226. Available from: https://www.publichealth.va.gov/epidemiology/reports/oefoifond/health-care-utilization/. Accessed 17 Apr 2019.

- 4.Cesur R, Sabia JJ, Tekin E. The psychological costs of war: military combat and mental health. J Health Econ. 2013;32(1):51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmar CR. Mental health impact of Afghanistan and Iraq deployment: meeting the challenge of a new generation of veterans. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(6):493–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramchand R, Rudavsky R, Grant S, Tanielian T, Jaycox L. Prevalence of, risk factors for, and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in military populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(5):37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maguen S, Lucenko BA, Reger MA, Gahm GA, Litz BT, Seal KH, et al. The impact of reported direct and indirect killing on mental health symptoms in Iraq war veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(1): 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baiocchi D, Baiocchi D. Measuring Army Deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan [Product Page]. RAND Corporation; 2013; updated 2013. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR145.html. Accessed 24 Apr 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisen SV, Schultz MR, Glickman ME, Vogt D, Martin JA, Osei-Bonsu PE, et al. Postdeployment resilience as a predictor of mental health in operation enduring freedom/operation iraqi freedom returnees. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):754–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barber J, Bayer L, Pietrzak RH, Sanders KA. Assessment of rates of overweight and obesity and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in a sample of Operation Enduring Freedom/ Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Mil Med. 2011;176(2):151–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stefanovics EA, Potenza MN, Pietrzak RH. The physical and mental health burden of obesity in U.S. veterans: results from the National Health and resilience in veterans study. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maguen S, Madden E, Cohen B, Bertenthal D, Neylan T, Talbot L, et al. The relationship between body mass index and mental health among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(Suppl 2):S563–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, Washington DL, Lee J, Haskell S, et al. The obesity epidemic in the veterans health administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(Suppl 1):11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rush T, LeardMann CA, Crum-Cianflone NF. Obesity and associated adverse health outcomes among US military members and veterans: findings from the millennium cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(7):1582–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberger PH, Ning Y, Brandt C, Allore H, Haskell S. BMI trajectory groups in veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Prev Med. 2011;53(3):149–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haskell SG, Brandt C, Burg M, Bastian L, Driscoll M, Goulet J, et al. Incident cardiovascular risk factors among men and women veterans after return from deployment. Med Care. 2017;55(11): 948–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Sayam S, Shao X, Wang K, Zheng S, Li Y, et al. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among veterans, United States, 2005–2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masodkar K, Johnson J, Peterson MJ. A review of posttraumatic stress disorder and obesity: exploring the link. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vieweg WV, Julius DA, Fernandez A, Tassone DM, Narla SN, Pandurangi AK. Posttraumatic stress disorder in male military veterans with comorbid overweight and obesity: psychotropic, antihypertensive, and metabolic medications. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(1):25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vieweg WV, Julius DA, Bates J, Quinn JF 3rd, Fernandez A, Hasnain M, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for obesity among male military veterans. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(6):483–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arksey HOM. L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.@EndNoteNews. EndNote | Clarivate Analytics: @EndNoteNews; 2019. Available from: https://endnote.com/. Accessed 24 Apr 2019.

- 25.Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, Amick MA, Kenna A, Milberg WP, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(1):25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Initial Assessment of Readjustment Needs of Military Personnel V, and Their Families. Returning Home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Preliminary Assessment of Readjustment Needs of Veterans, Service Members, and Their Families. 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220068/. Accessed 14 Jun 2019. [PubMed]

- 27.Gilmore AK, Brignone E, Painter JM, Lehavot K, Fargo J, Suo Y, et al. Military sexual trauma and co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder, depressive disorders, and substance use disorders among returning Afghanistan and Iraq veterans. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26(5):546–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haskell SG, Gordon KS, Mattocks K, Duggal M, Erdos J, Justice A, et al. Gender differences in rates of depression, PTSD, pain, obesity, and military sexual trauma among Connecticut War Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(2):267–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dauterive IE, Copeland LA, Pandey N. Association of military sexual trauma, post-tramautic stress disorder with obesity in female veterans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:S935 https://gi.org/2015/10/13/poster-1935-association-of-military-sexualtrauma-post-traumatic-stress-disorder-with-obesity-in-female-veterans/. Accessed 18 Nov 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson LC. The prevalence of military sexual trauma: a meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19(5):584–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimerling R, Street AE, Pavao J, Smith MW, Cronkite RC, Holmes TH, et al. Military-related sexual trauma among veterans health administration patients returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1409–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blais RK, Brignone E, Maguen S, Carter ME, Fargo JD, Gundlapalli AV. Military sexual trauma is associated with post-deployment eating disorders among Afghanistan and Iraq veterans. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(7):808–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimerling R, Gima K, Smith MW, Street A, Frayne S. The veterans health administration and military sexual trauma. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pandey N, Ashfaq SN, Dauterive EW 3rd, MacCarthy AA, Copeland LA. Military sexual trauma and obesity among women veterans. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2018;27(3):305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eating Disorders. 2019. Available from: https://www.apa.org/topics/eating. Accessed 22 Apr 2019.

- 36.Leehr EJ, Krohmer K, Schag K, Dresler T, Zipfel S, Giel KE. Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity–a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;49:125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoerster KD, Jakupcak M, Hanson R, McFall M, Reiber G, Hall KS, et al. PTSD and depression symptoms are associated with binge eating among US Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Eat Behav. 2015;17:115–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoenfeld AJ, Dunn JC, Bader JO, Belmont PJ Jr. The nature and extent of war injuries sustained by combat specialty personnel killed and wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq, 2003–2011. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(2):287–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maguen S, Cohen B, Cohen G, Madden E, Bertenthal D, Seal K. Eating disorders and psychiatric comorbidity among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22(4):e403–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slane JD, Levine MD, Borrero S, Mattocks KM, Ozier AD, Silliker N, et al. Eating behaviors: prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity, and associations with body mass index among male and female Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Mil Med. 2016;181(11):e1650–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine AB, Levine LM, Levine TB. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cardiometabolic disease. Cardiology. 2014;127(1):1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van den Berk-Clark C, Secrest S, Walls J, Hallberg E, Lustman PJ, Schneider FD, et al. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder and lack of exercise, poor diet, obesity, and co-occuring smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018;37(5):407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fulton JJ, Calhoun PS, Wagner HR, Schry AR, Hair LP, Feeling N, et al. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in operation enduring freedom/operation Iraqi freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans: a meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;31:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen BE, Marmar C, Ren L, Bertenthal D, Seal KH. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with mental health diagnoses in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans using VA health care. JAMA Intern Med. 2009;302(5):489–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.••.Blessing EM, Reus V, Mellon SH, Wolkowitz OM, Flory JD, Bierer L, et al. Biological predictors of insulin resistance associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in young military veterans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;82:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A diagnosis of PTSD in young male Veterans without cardiometabolic disease was associated with increased insulin resistance. Strategies to reduce cardiometabolic risk in this population are indicated.

- 46.LeardMann CA, Woodall KA, Littman AJ, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Smith B, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder predicts future weight change in the millennium cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(4):886–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.US Department of Veterans Affairs VHA. Reports on OEF/OIF/OND Veterans - Public Health. 2019; updated 20190226. Available from: https://www.publichealth.va.gov/epidemiology/reports/oefoifond/index.asp. Accessed 18 Apr 2019.

- 48.Batch BC, Goldstein K, Yancy WS Jr, Sanders LL, Danus S, Grambow SC, et al. Outcome by gender in the veterans health administration motivating overweight/obese veterans everywhere weight management program. J Women’s Health. 2018;27(1):32–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koo KH, Hebenstreit CL, Madden E, Seal KH, Maguen S. Race/ethnicity and gender differences in mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(3):724–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Littman AJ, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Powell TM, Smith TC. Millennium cohort study T. weight change following US military service. Int J Obes. 2013;37(2):244–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kittel JA, DeBeer BB, Kimbrel NA, Matthieu MM, Meyer EC, Gulliver SB, et al. Does body mass index moderate the association between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and suicidal ideation in Iraq/Afghanistan veterans? Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:123–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.NIH Physical Activity Guidelines 2019; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/. Accessed 28 Apr 2019.

- 54.Hoerster KD, Jakupcak M, McFall M, Unutzer J, Nelson KM. Mental health and somatic symptom severity are associated with reduced physical activity among US Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Prev Med. 2012;55(5):450–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Belmont PJ Jr, Goodman GP, Zacchilli M, Posner M, Evans C, Owens BD. Incidence and epidemiology of combat injuries sustained during “the surge” portion of operation Iraqi freedom by a U.S. Army brigade combat team. J Trauma. 2010;68(1):204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(5):453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kontos AP, Kotwal RS, Elbin RJ, Lutz RH, Forsten RD, Benson PJ, et al. Residual effects of combat-related mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(8):680–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ling G, Bandak F, Armonda R, Grant G, Ecklund J. Explosive blast neurotrauma. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(6):815–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26(3):e1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cifu DX, Taylor BC, Carne WF, Bidelspach D, Sayer NA, Scholten J, et al. Traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and pain diagnoses in OIF/OEF/OND veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Higgins DM, Kerns RD, Brandt CA, Haskell SG, Bathulapalli H, Gilliam W, et al. Persistent pain and comorbidity among operation enduring freedom/operation Iraqi freedom/operation new Dawn veterans. Pain Med. 2014;15(5):782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Higgins D, Buta E, Heapy A, Driscoll M, Kerns R, Masheb R, et al. The relationship among BMI, pain intensity, and musculoskeletal diagnoses. J Pain. 2016;17(4):S28. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Outcalt SD, Ang DC, Wu J, Sargent C, Yu Z, Bair MJ. Pain experience of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(4):559–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.••.Buta E, Masheb R, Gueorguieva R, Bathulapalli H, Brandt CA, Goulet JL. Posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis and gender are associated with accelerated weight gain trajectories in veterans during the post-deployment period. Eat Behav. 2018;29:8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A PTSD diagnosis was correlated with higher weight gain trajectories post-deployment in both women and men, with a slightly stronger association in women. Screening and treatment of psychological comorbitity is needed as well as weight management services young Veterans.

- 65.Malhotra R, Ostbye T, Riley CM, Finkelstein EA. Young adult weight trajectories through midlife by body mass category. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(9):1923–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wallace T, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C, National Heart L, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):e13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolf EJ, Miller DR, Logue MW, Sumner J, Stoop TB, Leritz EC, et al. Contributions of polygenic risk for obesity to PTSD-related metabolic syndrome and cortical thickness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolf EJ, Bovin MJ, Green JD, Mitchell KS, Stoop TB, Barretto KM, et al. Longitudinal associations between post-traumatic stress disorder and metabolic syndrome severity. Psychol Med. 2016;46(10):2215–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.An Introduction to Recharge for Whole Health - Whole Health For Life 2018; updated 20181003. Available from: https://www.va.gov/PATIENTCENTEREDCARE/Veteran-Handouts/An_Introduction_to_Recharge_for_Whole_Health.asp. Accessed 29 Apr 2019.

- 71.Kilbourne AM, Barbaresso MM, Lai Z, Nord KM, Bramlet M, Goodrich DE, et al. Improving physical health in patients with chronic mental disorders: twelve-month results from a randomized controlled collaborative care trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(1): 129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pomerantz AS, Sayers SL. Primary care-mental health integration in healthcare in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guerrero AP, Takesue CL, Medeiros JH, Duran AA, Humphry JW, Lunsford RM, et al. Primary care integration of psychiatric and behavioral health services: a primer for providers and case report of local implementation. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(6): 147–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whitworth JW, Ciccolo JT. Exercise and post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans: a systematic review. Mil Med. 2016;181(9):953–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldstein LA, Mehling WE, Metzler TJ, Cohen BE, Barnes DE, Choucroun GJ, et al. Veterans group exercise: a randomized pilot trial of an integrative exercise program for veterans with posttraumatic stress. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stanton MV, Matsuura J, Fairchild JK, Lohnberg JA, Bayley PJ. Mindfulness as a weight loss treatment for veterans. Front Nutr. 2016;3:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moin T, Damschroder LJ, AuYoung M, Maciejewski ML, Datta SK, Weinreb JE, et al. Diabetes prevention program translation in the veterans health administration. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(1):70–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maciejewski ML, Shepherd-Banigan M, Raffa SD, Weidenbacher HJ. Systematic review of behavioral weight management program MOVE! For veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(5):704–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kahwati LC, Lewis MA, Kane H, Williams PA, Nerz P, Jones KR, et al. Best practices in the veterans health Administration’s MOVE! Weight management program. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(5):457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maguen S, Hoerster KD, Littman AJ, Klingaman EA, Evans-Hudnall G, Holleman R, et al. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with PTSD participate less in VA’s weight loss program than those without PTSD. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Skoyen JA, Rutledge T, Wiese JA, Woods GN. Evaluation of TeleMOVE: a Telehealth Weight Reduction Intervention for Veterans with Obesity. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(4):628–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rutledge T, Skoyen JA, Wiese JA, Ober KM, Woods GN. A comparison of MOVE! Versus TeleMOVE programs for weight loss in veterans with obesity. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2017;11(3):344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Goodrich DE, Lowery JC, Burns JA, Richardson CR. The phased implementation of a National Telehealth Weight Management Program for veterans: mixed-methods program evaluation. JMIR Diabetes. 2018;3(3):e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weingardt KR, Greene CJ. New electronic tools for veterans. N C Med J. 2015;76(5):332–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.VA EHR Modernization - EHRM Fact Sheet 2019; Available from: https://www.ehrm.va.gov/resources/factsheet. Accessed 1 May 2019.

- 86.EHRIntelligence. EHR and the VA: Part I - History: @EHRIntel; 2012; updated 2012-04-19. Available from: https://ehrintelligence.com/news/ehr-and-the-va-part-i-history. Accessed 1 May 2019.