Abstract

Background

Splenic rupture is an emergency condition and a vast number of cases are secondary to trauma. Several underlying pathologies have also been associated with splenic rupture, such as hematological diseases, malignancies, and infectious and inflammatory diseases.

Case presentation

The patient was a 52-year-old man who referred to the Poursina Hospital in Rasht while complaining of abdominal pain from the day before hospitalization. The patient reported a history of lethargy, fever, and nausea. In the examinations performed, there was a brief tenderness in the patient’s epigastrium. The patient was monitored and about 12 h after hospitalization, ill appearance, respiratory (respiratory distress) symptoms, and high fever were reported for the patient. According to the examination, the patient was immediately transferred to the operating room and underwent laparotomy. During the operation, contrary to our expectations, a lot of blood (about 1000 cc) was observed in the patient’s abdomen. After blood suctioning, the left upper quadrant (LUQ) was bleeding and the rupture of the spleen could also be observed. Therefore, a splenectomy was performed. In the examinations performed for the patient, the patient’s rtPCR test confirmed COVID-19.

Conclusion

The evaluation of the spontaneous splenic rupture (SSR) in our case shows that this type of risk should also be considered in patients with COVID-19 who refer to medical centers with abdominal pain, and if more cases are reported, the correctness of this process can be commented on.

Keywords: Case report, Surgery, Spleen, COVID-19

Background

Splenic rupture is an emergency condition and a vast number of cases are secondary to trauma. Several underlying pathologies have also been associated with splenic rupture, such as hematological diseases, malignancies, and infectious and inflammatory diseases [1–3]. Atraumatic splenic rupture (ASR) is rare [1, 2]. Splenic rupture is not considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in the absence of trauma, the results of which may be catastrophic [4].

The diagnosis of splenic rupture is a clinical finding confirmed by either Computed tomography scan (CT scan) or laparotomy (in hemodynamically unstable patients). Several grading systems have been established for splenic rupture based on CT scan or ultrasound findings and each has been found to be effective in contributing to management and decision making [4].

However, there has been a tremendous amount of case reports of atraumatic splenic rupture, there are not any comprehensive assessment to reveal the incidence rate, causes, specific symptoms, available management methods, and the prognosis [3].

Case presentation

The patient was a 52-year-old man who referred to the Poursina Hospital in Rasht while complaining of abdominal pain from the day before hospitalization. The patient reported a history of tiredness, fever, and nausea. In the examinations performed, there was a brief tenderness in the patient’s epigastrium. The patient’s initial pressure was 80.120 with a pulse rate of 95. The patient’s fever was not detected upon arrival. For the patient, an upright abdominal radiograph, abdominal and pelvic ultrasounds, and blood tests including CBC,BUN,Cr,PT,PTT,INR,LFT,Amylase,Lipase,LDH were requested.

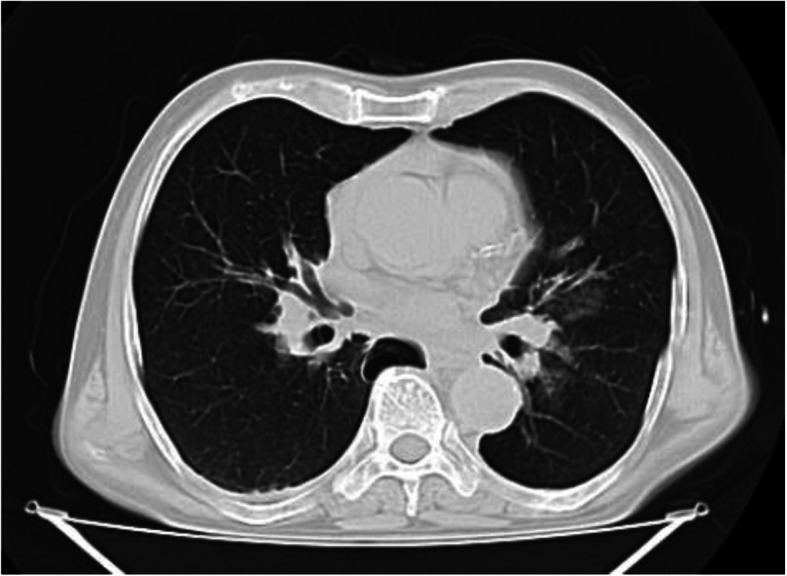

The patient’s upright abdominal radiograph was normal. Perihepatic and perisplenic fluid and gallstones were seen on the patient’s ultrasound. On laboratory findings, White Blood Cells (WBC) = 4000 /μL with 30% lymphocytes were reported. Hemoglobin (Hb) = 11 g/dL and Platelets (PLT) = 245,000 /μL were found. Other findings were normal. No pathological lesion was observed on the patient’s lung CT scan (Fig. 1). A small amount of perihepatic and perisplenic fluid was observed on the patient’s CT scan (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Primary lung CT scan. No pathological lesion was observed on upon arrival lung CT scan of the patient

Fig. 2.

Abdomen view in Primary CT scan. A small amount of perihepatic and perisplenic fluid was observed on the patient’s CT scan

The patient was monitored and about 12 h after hospitalization, ill appearance, respiratory (respiratory distress) symptoms, and high fever were reported for the patient. The patient’s O2Sat was 96%. Due to the exacerbation of the patient’s respiratory symptoms, the CT scan of the lungs was requested again for the patient and the tests were repeated for suspicion of coronavirus.

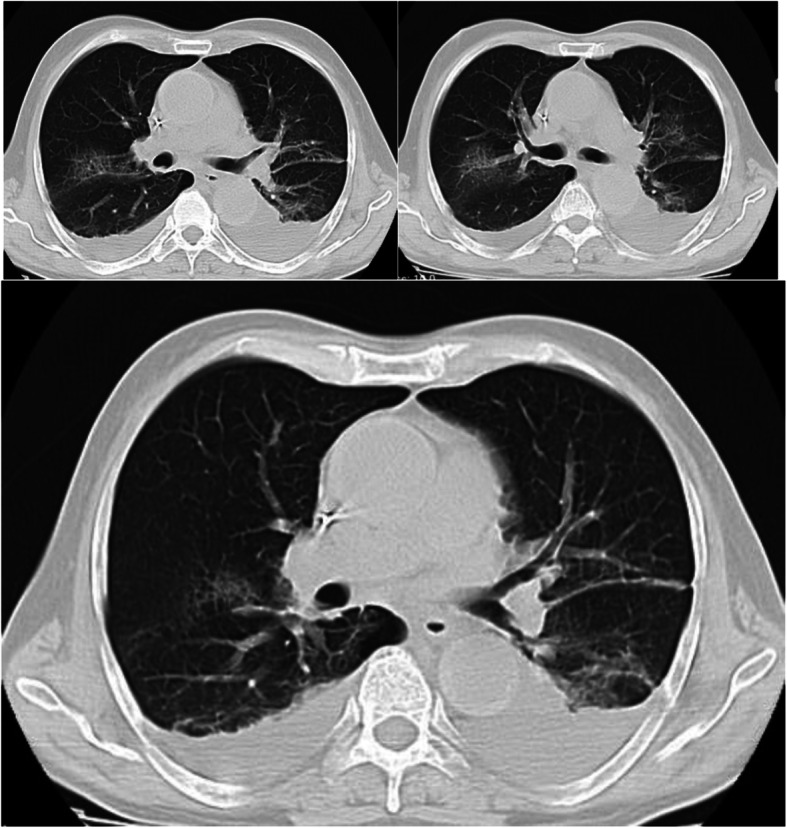

The second CT scan was performed about 18 h after the initial examination. Patchy ground-glass lesions along with bilateral pleural effusion were seen on the CT scan of the patient’s lungs (Fig. 3). A bilateral chest tube was inserted for the patient according to the volume of the fluid, and according to the patient’s CT scan and respiratory symptoms, he was transferred to the specialized COVID-19 unit. In the new blood tests, Hb = 9.5 g/dL, WBC = 4800/μL, and PLT = 195,000 /μL were observed. An extensive fluid collection around the spleen was observed on the CT scan performed for the patient (Fig. 4). The examination of the patient’s abdomen changed significantly about 20 h after the initial examination and became generalized rebound tenderness. However, the patient’s blood pressure was still 70.110 and the pulse rate was 90. According to the examination, the patient was immediately transferred to the operating room and underwent laparotomy. During the operation, contrary to our expectations, a lot of blood (about 1000 cc) was observed in the patient’s abdomen. After blood suctioning, the left upper quadrant was bleeding and the rupture of the spleen could also be observed. Therefore, a splenectomy was performed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Secondary lung CT scan. The second CT scan was performed about 18 h after the initial examination. Patchy ground-glass lesions along with bilateral pleural effusion were seen on the CT scan of the patient’s lungs

Fig. 4.

Abdomen view in Secondary CT scan. An extensive fluid collection around the spleen was observed on the CT scan performed for the patient

Fig. 5.

Appearance of the spleen after splenectomy. The rupture of the spleen could also be observed. Therefore, a splenectomy was performed

In the examinations performed for the patient, the patient’s PCR confirmed COVID-19. The patient was admitted to the ICU after surgery, and within 3 days after surgery, the patient was extubated. The patient’s chest tubes were removed within 1 week after the surgery according to the radiographs performed. After a concomitant treatment for COVID-19 and during a two-week hospital stay, the patient was discharged in good general condition.

During the examinations performed and the history taken several times from the patient and the patient’s companion, no history of the trauma was given and the changes in the patient’s CT scan and the patient’s examinations occurred very quickly.

The LE cell, ANA, and HIV as well as the Monospot, RF and Wright agglutination test were negative. The peripheral blood smear and the Widal agglutination test were negative for malaria and VCA Antibody IgM and IgG were negative for Epstein - Barr virus (EBV).

In the macroscopic study of splenic pathology, a spleen tissue with dimensions of 11× 8 × 5 cm and a weight of 350 g and a laceration with a size of 2 × 2 cm were observed and in the microscopic study, a focally hemorrhagic area was reported.

Discussion and conclusions

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses and the subset of Coronaviridae, ranging from the common cold virus to more serious diseases such as SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 [5, 6].

Depending on the type of coronavirus, the symptoms can range from common cold symptoms to fever, cough, shortness of breath, and acute respiratory problems. The patient may also have a seemingly unexplained cough for several days. Unlike the SARS, the MERS-coronavirus (MERS-CoV) affects not only the respiratory system but also other vital organs in the body, such as the kidneys and the liver. In acute cases, gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea, acute respiratory failure, blood coagulation disorders, and renal failure have also been reported, which may lead to the patient’s need for hemodialysis [5–7].

Some people have no symptoms or only mild symptoms. But in other people, COVID-19 can lead to serious problems such as pneumonia, not getting enough oxygen, and even death [6]. These symptoms are more common in people with other underlying problems, given that coronavirus symptoms and their effects on various organs are currently unknown and under investigation [6, 7].

There are several causes for the atraumatic splenic rupture (ASR):

Infectious causes, blood and metabolic diseases, pathophysiological disorders and iatrogenic conditions along with splenic rupture, Infectious mononucleosis (IM, mono) are the other causes of the atraumatic splenic rupture [4].

A patient with infectious mononucleosis and splenic enlargement (splenomegaly) should be closely monitored. The pathologic splenic rupture is the most common cause of death in patients with infectious mononucleosis [4]. It has been believed that increased intra-abdominal pressure or diaphragmatic contraction during severe coughing, vomiting, and defecation which leads to pressure on the spleen, is the cause of this type of splenic rupture [8]. However, Patel et al. believed that this was primarily the result of a progressive subcapsular hematoma that subsequently ruptured the capsule and caused hemoperitoneum [9]. Splenic rupture is traditionally treated with splenectomy. It is reasonable to avoid the possibility of sudden death as an early complication of splenic rupture and the risk of blood transfusions. Initially, the reconstruction of the spleen was considered as an option, but the difficulty in implementing this technique due to the enlargement and easy rupture of a sick spleen and the increased likelihood of rebleeding made it less desirable [9]. Based on the role of the spleen in immunity and overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI), there is a tendency to conservative management of splenic rupture in hemodynamically stable patients [9]. The survival rate of splenectomy in these patients in articles is close to 100% [10, 11]. Despite the potential death caused by the rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis, the survival benefit is superior to the risk of sepsis due to post-splenectomy infection [10, 11].

Malaria is another cause of splenic rupture in malaria-prone areas. Most splenic rupture occurs in the acute phase of infection [12, 13]. In people undergoing hemodialysis and receiving heparin, non-traumatic rupture of the spleen has been reported because the edema of the spleen causes a hematoma under the splenic capsule. In people who are under treatment with thrombolytic drugs or taking anticoagulant drugs, a disturbance in the mechanism of homeostasis causes splenic rupture due to minor bumps [14, 15]. According to the above-mentioned discussions, can COVID-19 be another infectious cause of spontaneous splenic rupture (SSR)? Examining this issue requires further investigation and waiting for similar reports.

The evaluation of the spontaneous splenic rupture (SSR) in our case shows that this type of risk should also be considered in patients with COVID-19 who referred to medical centers with abdominal pain, and if more cases are reported, the correctness of this process can be commented on.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- LUQ

Left Upper Quadrant

- rtPCR

real-time Polymerase chain reaction

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SSR

Spontaneous Splenic Rupture

- ASR

Atraumatic Splenic Rupture

- CT scan

Computed tomography scan

- CBC

Complete Blood Count

- BUN

Blood Urea Nitrogen

- Cr

Creatinine

- PT

Prothrombin Time

- PTT

Partial Thromboplastin Time

- INR

International Normalized Ratio

- LFT

Liver Function Test

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- WBC

White Blood Cells

- PLT

Platelets

- HB

Hemoglobin

- O2Sat

Oxygen Saturation

- LE cell

Lupus Erythematosus cell

- ANA

Anti-Nuclear Antibody

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- IgM

Immunoglobulin M

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- VCA Antibody

Viral Capsid Antigen antibody

- Cm

Centimeters

- SARS

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

- MERS

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome

- MERS-CoV

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

- IM

Infectious Mononucleosis

Authors’ contributions

Study conception and design: M M. Acquisition of data: SY. Analysis and interpretation of data: MS M. Drafting of manuscript: A S. Critical revision: M M. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

There has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent to participate: Not applicable

Ethics approval Reg. No: IR99110

Poursina Hospital Surgery Research Center Ethic Committee.

Consent for publication

Satisfaction letter and written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

We know of no conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Al Mashat FM, Sibiany AM, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung KA, Rafaat M. Eruption associated with amoxicillin in a patient with infectious mononucleosis. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:553–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01699_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieberman ME, Levitt MA. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: a case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(1):28–31. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(89)90079-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver H, Kumar V, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture: A rare life-threatening condition; Diagnosed early and managed successfully. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:13–15. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.883739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei X-S, Wang X, Niu Y-R, Ye L-L, Peng W-B, Wang Z-H, Yang W-B, Yang B-H, Zhang J-C, Ma W-L, Wang X-R. Clinical Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Infected Pneumonia with Diarrhea. Rochester, NY; 2020. SSRN 3546120 Check |ssrn = value (help). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3546120.

- 6.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai C-C, Shih T-P, Ko W-C, Tang H-J, Hsueh P-R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. 2020;55(3):105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Won ACM, Ethell A. Spontaneous splenic rupture resulted from infectious mononucleosis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3(3):97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel JM, Rizzolo E, Hinshaw JR. Spontaneous subcapsular splenic hematomas as the only clinical manifestation of infection mononucleosis. JAMA. 1982;247:3243–3244. doi: 10.1001/jama.1982.03320480059027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutkow I. Rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis. Arch Surg. 1978;113:718–720. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1978.01370180060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stockinger ZT. Infectious mononucleosis presenting as spontaneous splenic rupture without other symptoms. Mil Med. 2003;168(9):722–724. doi: 10.1093/milmed/168.9.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiménez BC, Navarro M, Huerga H, López-Vélez R. Spontaneous splenic rupture due to Plasmodium vivax in a traveler: case report and review. J Travel Med. 2007;14:188–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozsoy MF, Oncul O, Pekkafali Z, Pahsa A, Yenen OS. Splenic complications in malaria: report of two cases from Turkey. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:1255–1258. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opatrny K., Jr Hemostasis disorders in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl. 1997;62:S87–S89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zbrog Z, Pawlicki L. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as a cause of death of a patient with uremia. Pol Tyg Lek. 1989;44:232–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.