Abstract

The role of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) as a chemo-preventive and adjuvant therapeutic agent for cancers is generating attention. Mounting evidence indicates that aspirin reduces the incidence and mortality of certain obesity-related cancers, particularly colorectal cancer. In endometrial cancer, previous studies examining the effect of aspirin remain inconsistent as to the reduction in the risk of endometrial cancer. While some evidence indicates protective effects in obese women, other studies have showed a potential deleterious effect of these medications on endometrial cancer outcomes. However, exposure measurement across studies has been inconsistent in recording dose, duration, and frequency of use; thus making comparisons difficult. In this article, we review the evidence for the association between endometrial cancer and obesity, the pharmacological differences between regular- and low-dose aspirin, as well as the potential anti-tumor mechanism of aspirin, supporting a possible therapeutic effect on endometrial cancer. A proposed mechanism behind decreased cancer mortality in endometrial cancer may be a result of inhibition of metastasis via platelet inactivation and possible prostaglandin E2 suppression by aspirin. Additionally, aspirin use in particular may have a secondary benefit for obesity-related comorbidities including cardiovascular disease in women with endometrial cancer. Although aspirin-related bleeding needs to be considered as a possible adverse effect, the benefits of aspirin therapy may exceed the potential risk in women with endometrial cancer. The current evidence reviewed herein has resulted in conflicting findings regarding the potential effect on endometrial cancer outcomes, thus indicating that future studies in this area are needed to resolve the effects of aspirin on endometrial cancer survival, particularly to identify specific populations that might benefit from aspirin use.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, Aspirin, Risk, Survival, Review

1. Introduction

Aspirin in its medicinal form has been used for its analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties for over a century [1]. Following elucidation of the anti-platelet effects of aspirin, the beneficial effects of low-dose aspirin for the primary and secondary prevention of cardio-vascular disease (CVD) have been established [2]. Recently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended “initiating low-dose aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD and colorectal cancer in adults aged 50 to 59 years who have a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk, are not at increased risk for bleeding, have a life expectancy of at least 10 years, and are willing to take low-dose aspirin daily for at least 10 years” [3]. While there is extensive evidence supporting the long-term use of aspirin for colorectal cancer prevention [4,5], evidence is building for decreasing overall risk and risk of metastasis in other malignancies such as esophageal and stomach cancer [4–7].

It is important to note that there are few studies focusing specifically on endometrial cancer, and caution should be taken in extrapolating results from other solid tumor types with varying histology to an individual disease. As such, the objective of this paper is to review current mechanistic and clinical evidence surrounding the effects of aspirin use on endometrial cancer risk and outcomes.

Endometrial cancer continues to be the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, with >61,000 newly diagnosed cases projected in 2017 [8]. Although the mortality rate in endometrial cancer patients is generally low, the survival rate for obese patients or those with metastatic or recurrent disease is significantly lower [9,10]. Established risk factors of endometrial cancer include obesity, unopposed estrogen therapy, tamoxifen use, nulliparity, polycystic ovarian syndrome, Lynch syndrome, early menarche, late menopause, and insulin resistance [9,11].

Over the last three decades, endometrial cancer has been commonly classified into two pathogenic types, although a lack of consensus for assigning these histotypes and the increasing ability to define tumor genotype is leading to a more precise molecular classification system [12]. Type I tumors are more common, generally arise in the setting of hyperestrogenism, are composed of low-grade endometrioid carcinoma, and carry an excellent prognosis [13]. Type II tumors, without clearly defined risk factors, are mainly represented by serous and clear cell carcinomas with an overall poor prognosis [12,14]. Endometrial cancer and colorectal cancer have many features in common, including risk factors, histopathologic progression from pre-cancerous lesion to carcinoma, as well as certain genetic mutations and microsatellite instability events [12,15]. These similarities lead to the hypothesis that some colorectal cancer findings, such as risk reduction with the use of aspirin, might be applicable to endometrial cancer.

2. Obesity, inflammation, and endometrial cancer

Obesity, the abnormal or excessive accumulation of body fat, is defined epidemiologically as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 among adults, and is an important risk factor for many chronic diseases, including type II diabetes, CVD, several cancers, and premature mortality [16]. Adipose tissue is a complex endocrine organ that secretes a variety of both anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines classified as adipokines, which contribute to a state of chronic systemic inflammation [11]. Chronic inflammation associated with obesity has been known to be a major factor contributing to progression of many cancers [11]. In this proposed mechanism, obesity stimulates inflammatory pathways that promote tumor development, mainly by release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These inflammatory cytokines then enhance angiogenesis, induce cell proliferation, suppress the immune system, and generate reactive oxygen species leading to DNA damage [17].

Obesity is also a well-established endometrial cancer risk factor. Incidence rates of endometrial cancer have steadily increased in the past two decades in parallel with the pandemic increase in the proportion of obesity in the United States [18]. Across all cancer sites, increased BMI and obesity is most strongly associated with endometrial cancer incidence and mortality [9–11,18].

The association between BMI and endometrial cancer is more prominent for type I endometrial cancer than type II endometrial cancer [14, 19]. Traditionally, unopposed estrogen has been thought to be the primary oncogenic mechanism for the development of type I endometrial cancer in obese women [11]. Adipose tissue contains the aromatase enzyme, which peripherally converts circulating androgens, primarily androstenedione, into excess estrogen. This causes continued stimulation of the endometrium, resulting in endometrial hyperplasia, which can subsequently progress to invasive cancer. Aromatase expression in the intra-tumoral stroma, further contributes to intra-tumoral estrogen biosynthesis in endometrial carcinoma [20]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) production is stimulated by 17β-estradiol in endometrial cancer cells and induces aromatase expression in intra-tumoral stromal cells, promoting further E2 synthesis. This positive feedback loop further stimulates tumor cells.

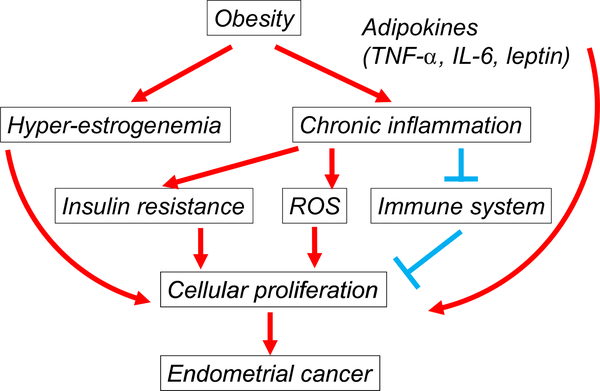

Recent studies have elucidated that chronic inflammation related to obesity can be an important alternative mechanism of endometrial oncogenesis (Fig. 1) [21,22]. Inflammation contributes to the development of endometrial cancer in conjunction with estrogen exposure. Elevated serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, and C-reactive protein (CRP) are associated with inflammation, and CRP in particular has been consistently associated with a statistically increased risk of endometrial cancer [22,23]. Chronic systemic inflammation associated with obesity augments the development of insulin resistance and chronic hyper-insulinemia, independent risk factors for the development of endometrial cancer [11]. The activation of pro-inflammatory pathways induced by TNF-α, over-expressed in adipose tissue, leads to a state of insulin resistance. The direct association between estrogen receptors and cell surface receptors, including insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGFR-1) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), induces activation of many signaling pathways including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway that promotes breast cancer cell growth and tumor progression [24]. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is known to be over-activated in a large fraction of endometrial cancers, due to loss of the tumor suppressor gene phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN). PTEN inactivation or loss is observed in >40% of type I endometrial cancers [11]. Leptin, a protein secreted from white adipose tissue, has been known to stimulate the proliferation of various types of cancer cells including endometrial cancer via multiple signal transduction pathways [25]. Leptin-induced functional activation of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 is related to Janus-activated kinase 2 (JAK2)/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and PI3K/AKT-dependent, indicating that COX-2/prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) signaling may be a critical pathway of endometrial carcinogenesis in the setting of obesity [25]. Thus, suppression of obesity-related inflammation and subsequent reduction in PGE2, as would theoretically be achieved with use of aspirin, could be a promising strategy for the treatment of endometrial cancer.

Fig. 1.

Impact of obesity in endometrial cancer progression. Excess estrogen from peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogen, mainly androstenedione in adipose tissue, causes continued stimulation of the endometrium to develop endometrial cancer. Adipose tissue also secretes a variety of both anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines classified as adipokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and leptin), which cause a state of chronic systemic inflammation. Chronic inflammation promotes cellular proliferation, mainly by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, enhancing insulin resistance, suppressing the immune system, and generating reactive oxygen species for DNA damage. Abbreviations: TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-6, Interleukin-6; and ROS, reactive oxygen species.

3. Aspirin pharmacology and mechanisms of action

Aspirin exerts its anti-inflammatory effects primarily via inhibition of COX, a key enzyme responsible for prostaglandin biosynthesis from arachidonic acid (AA) (Fig. 2). Two major isoforms of COX, COX-1 and COX-2, catalyze the conversion of AA to prostanoids which are then metabolized by tissue-specific synthases to different prostanoids including PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, thromboxane A2 (TXA2) and prostacyclin [26]. Released prostanoids regulate different functions through interaction with G-protein coupled receptors. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in most tissues and is highly expressed in platelets, where it is involved with platelet activation via the generation of TXA2, and in gastric epithelial cells where it protects gastric mucosa via the generation of PGE2. COX-2 is expressed in several tissues and is induced in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to PGE2 production. Aspirin irreversibly inactivates both COX-1 and COX-2 and has several different pharmacological effects. These range from anti-platelet action at low doses to anti-inflammatory action at high doses. These effects are dependent on drug availability in the target tissue, and recovery of COX activity can only occur through de novo enzyme synthesis [27].

Fig. 2.

Aspirin: mechanism of action against cyclooxygenase pathway. Aspirin exerts its anti-inflammatory effects mainly by inhibiting COX, a key enzyme responsible for PG biosynthesis from AA. Two major isoforms of COX, COX-1 and COX-2, catalyze the conversion of AA to prostanoids which are metabolized by tissue-specific synthases to different prostanoids. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in most tissues and is highly expressed in platelets, where it is involved with platelet activation via the generation of TXA2, and gastric epithelial cells where it protects gastric mucosa via the generation of PGE2. COX-2 is expressed in several tissues and is induced in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can lead to PGE2 production. Aspirin irreversibly inactivates both COX-1 and COX-2 and has several different pharmacological effects ranging from anti-platelet action at low doses to anti-inflammatory action at high doses is dependent on drug availability in the target tissue and recovery of COX activity through de novo enzyme synthesis. Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; PG, prostaglandin; COX, cyclooxygenase; TXA2, thromboxane A2; and GI, gastrointestinal.

Aspirin affects cells containing COX-2 via acetylation of vascular COX-2 by redirecting the catalytic activity of COX-2 away from the generation of prostaglandin or thromboxane intermediates and towards the production of intermediates of 15-epimeric lipoxin A4, also known as aspirin triggered 15-epi-lipoxin A4 (ATL) [27]. ATL functions as a local endogenous anti-inflammatory mediator. Although resolution of inflammation has traditionally been thought to be due to a passive gradual decrease in signaling via inflammatory mediators, it has recently been shown to be a tightly regulated active process involving ATL [28]. ATL is classified into a larger group of “immune-resolvents” which have been shown in both in vitro and in vivo to be responsible for inflammation resolution [28,29]. In a recent double-blinded randomised clinical trial, ATL was demonstrated to be increased in the setting of daily aspirin therapy among healthy volunteers [30]. Notably, there was no difference in ATL level regardless of daily dose (81–650 mg) [30]. ATL may account in part for aspirin’s anti-tumor effect, which is distinct from the inhibitory effect of aspirin on platelet activity.

Aspirin irreversibly inactivates both COX-1 and COX-2 but is metabolized rapidly during its first pass through the liver, resulting in a very short half-life of 15–20 min [27]. The degree of inactivation is dependent on recovery of COX activity via de novo enzyme synthesis in the target cells. This inactivation of COX activity can be rapidly reversed by new protein synthesis in proliferating cells. Thus, in order to maintain a sustained inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes in nucleated cells, frequent (3–4 times per day) large doses (around 2000 mg/day) are needed [31].

The adequate dosage of aspirin required for the sustained inhibition of COX-2 is greater than that of low-dose aspirin. After long-term dosing with low-dose aspirin (100 mg/day), peak plasma concentrations of acetylsalicylic acid and salicylic acid in the systemic circulation amount only to 3.0 and 30 μM, respectively, which are not sufficient for the activation of the COX-independent pathways [32]. This concentration is insufficient to cause adequate and sustained acetylation of COX-2, as COX-2 is rapidly synthesized in proliferating cells. Moreover, the short half-life of aspirin makes it difficult to maintain a prolonged inhibitory effect. Therefore, the primary chemo-preventive function of aspirin is unlikely to be via the COX-2 pathway [7,31,33,34].

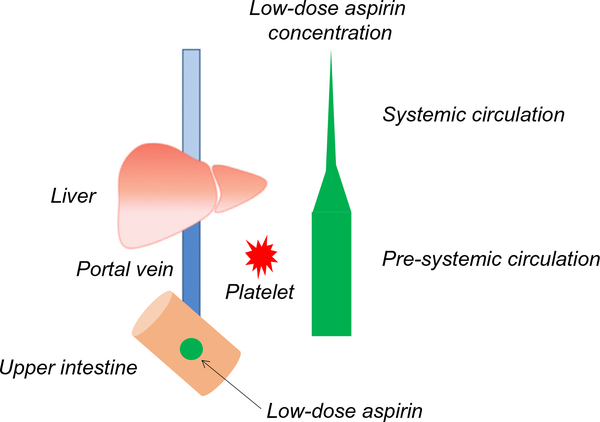

However, COX-1 activity in platelets, which are non-nucleated cells that cannot synthesize new enzyme, can be suppressed by daily low-dose aspirin. Aspirin affects platelet COX-1 activity with an IC50 value (concentration which inhibits by 50% the activity of COXs) of 18 μM in human whole blood [31]. Moreover, platelets pass through the portal (pre-systemic) circulation where the aspirin concentration is much higher than that in systemic circulation [27,35]. Inhibition of platelet COX-1 activity has been detected prior to aspirin reaching the systemic circulation [27], indicating that enzyme inhibition occurs in the portal (pre-systemic) circulation (Fig. 3). Enhanced platelet activation in patients with colorectal cancer has been demonstrated to be cumulatively inhibited by aspirin 50 mg daily for 5 consecutive days [36]. These findings indicate that daily administration of low-dose aspirin is sufficient to inactivate COX in non-nucleated cells, such as mature platelets.

Fig. 3.

Low-dose aspirin: decrease in plasma concentration after the first pass through the liver. Aspirin concentration is significantly different between pre-systemic circulation and systemic circulation. Low-dose aspirin (green circle) is absorbed in the upper intestine and circulated to the liver via portal vein. Low-dose aspirin concentration decreases after it is metabolized in the liver and further is diluted in the systemic circulation. The low-dose aspirin plasma concentration in the portal vein is sufficient for the inactivation of the platelet COX-1. Low-dose aspirin concentration is represented by the width of the green bar.

Although several COX-independent pathways have demonstrated anti-cancer effects in vitro studies, micromolar concentrations of aspirin are hypothesized to exert these effects based on the pharmacokinetic features of aspirin [1,32,37–39]. For example, inhibition of NF-kB signaling and Wnt/β-catenin signaling and the acetylation of extra-COX proteins have been suggested to play a role in the chemo-preventive effects of aspirin; however, these pathways have not yet been demonstrated to be clinically relevant [31].

More clinical data is available on low-dose aspirin compared to higher dose regimens based on its frequency of use for prevention of CVD. However, it is known that higher doses of aspirin have different physiologic effects than low-dose aspirin [40]. For example, the risk of peptic ulcers and bleeding increases with higher doses; however the optimal dose for chemo-preventive effects of aspirin even in colorectal cancer is not well established [40]. With regard to endometrial cancer, aspirin has been shown in vitro to exert dose-dependent inhibition of endometrial adenocarcinoma cells as well as to induce apoptosis and reduce the expression of B-cell lymphoma 2 (bcl-2), with larger doses having a more significant effect [41]; however, as discussed below, this observation has not been confirmed clinically.

4. PGE2 and endometrial cancer

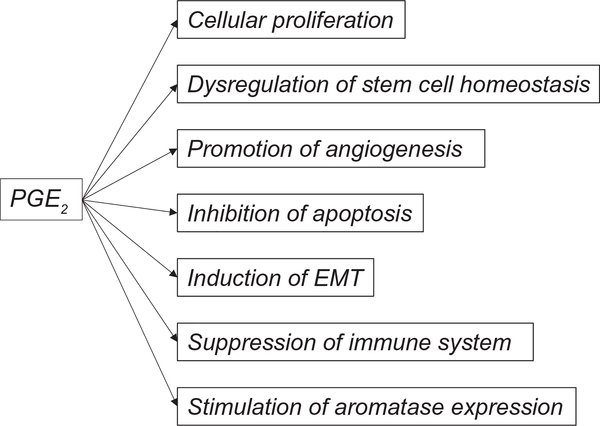

PGE2 is known to enhance cellular proliferation, promote angiogenesis, inhibit apoptosis, stimulate invasive behavior, and to induce the transition from epithelial to mesenchymal (EMT) phenotype. Additionally, it acts to regulate stem cell homeostasis, and to suppress the immune response (Fig. 4) [42]. Multiple studies have reported that PGE2 is associated with the pathogenesis of malignancy, and several studies have associated PGE2 with hormone dependent malignancies including endometrial and breast cancers [43,44]. Secreted PGE2 acts in either an autocrine or paracrine manner through four cognate G-protein coupled receptors, EP1 to EP4. PGE2 is up-regulated by the pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α or IL-1β [45]. It has been demonstrated that overexpression of COX-2 reduces the rate of apoptosis, increases the invasiveness of malignant cells, and promotes angiogenesis in colon cancer cells [46]. The most accepted anti-cancer action of aspirin is mediated through COX-2/PGE2 inhibition. Regular use of aspirin reduced the risk of colorectal cancer that over-expresses COX-2 but not the risk of colorectal cancer with weak or absent expression of COX-2 [38]. This indicates that COX-2/PGE2 may play an important role in oncogenesis.

Fig. 4.

PGE2 promotes cancer progression. PGE2 is a known factor for enhancement of cellular proliferation, promotion of angiogenesis, inhibition of apoptosis, stimulation of invasion, induction of the transition from EMT, regulation of stem cell homeostasis, and suppression of immune response. PGE2 also stimulates aromatase expression and thereby regulates estrogen production. Abbreviations: PG, prostaglandin; and EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Malignant endometrial cells have enhanced levels of COX-2 and PGE2 [43,47]. High COX-2 expression has also been associated with increasing endometrial cancer grade and depth of myometrial tumor invasion, and patients with COX-2-positive tumors show a trend towards shorter disease-free survival than those with COX-2-negative tumors [48]. It has also been suggested that PGE2 participates in tumorigenesis of endometrial cancers [49]. Malignant endometrial epithelial cells secrete PGE2 that regulates endometrial cancer cell function in an autocrine/paracrine manner via the EP2/EP4 receptors. This induces COX-2 expression in normal endometrial stromal cells in a paracrine fashion [43]. PGE2 signaling may promote endometrial tumorigenesis by inactivation of tuberin following its phosphorylation via the AKT signaling pathway [49].

Recently, PGE2 was demonstrated to promote proliferation and invasion by enhancing small ubiquitin-related modifier 1 activity via the EP4 receptor in endometrial cancer [47]. These findings support that functional activation of PGE2 is associated with progression of endometrial cancer. In addition to the aforementioned effects, PGE2 also stimulates aromatase expression and thereby upregulates estrogen production in breast cancer [50]. A positive correlation is observed between COX-2 and aromatase expression in type I endometrial cancer [51]. Specifically, in post-menopausal obese women, the primary source of estrogen comes from peripheral adipose tissue due to the increased levels of aromatase found in adipose tissue; thus, inhibition of PGE2 by aspirin results in reduced estrogen biosynthesis and provides a potential protective mechanism in estrogen receptor-positive endometrial cancer. These findings show that PGE2 is not only a poor prognostic factor for endometrial cancer but also may play a role in endometrial cancer progression.

Selective inhibition of platelet COX-1 has been found to prevent an increase in PGE2 biosynthesis and the induction of gene expression modifications associated with EMT, a critical event during tumor metastasis [35,52,53]. In lung adenocarcinoma cells, addition of pretreated platelets with low-dose aspirin to the cells prevented a platelet-induced increase in cytosolic calcium and subsequent calcium-mediated activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2, which yields the COX-2 substrate and PGE2, but does not alter the expression of COX-2 [35]. These results indicate that inhibition of platelet activation with low-dose aspirin reduced calcium mobilization in the tumor cells, thereby inhibiting synthesis of PGE2. These phenomena in colon and lung cancers may be generalizable to other adenocarcinomas, including endometrial cancer [5]. Moreover, low-dose aspirin reduced systemic basal PGE2 biosynthesis by 55% in healthy female volunteers [35]. The range of this reduction was comparable to that caused by a “non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) dose” in lung cancer, which has also demonstrated an anti-tumor effect [54].

5. Platelet relevance in endometrial cancer

Platelets are integral to the process of metastasis. The formation of platelet aggregates surrounding circulating tumor cells protects them from elimination by immune cells, promoting their arrest at the endothelium and preventing extravasation [55]. Activated platelets release a wide repertoire of mediators, including TXA2 and PGE2, α-granule contents (such as angiogenic factors, anti-angiogenic factors, growth factors, proteases and many cytokines), and different types of vesicles (exosomes) [1,31]. Thus, the released mediators contribute to the crosstalk among platelets, cancer cells, and other cells of the tumor microenvironment to induce several signaling pathways associated with phenotypic switch of the cellular compartment of the stromal environment. These events may create a tissue microenvironment that supports progression of endometrial carcinoma.

Adherence of platelets to colon and lung cancer cells induces activation of both the platelets and the cancer cells, and increases the biosynthesis of PGE2 from both cell types [35]. This crosstalk also provides cancer cells with high metastatic capacity. Following co-culture of human colon carcinoma cells with human platelets, they acquired a more aggressive phenotype by induction of mesenchymal-like cancer cells and stimulated platelet aggregation [52]. Platelet COX-1 inhibition by aspirin administration to mice, previously injected with platelet primed carcinoma cells, prevented the increased rate of metastasis as well as the enhanced production of TXA2 and PGE2 [52]. Moreover, suppression of platelet COX-1 with low-dose aspirin treatment averted the stem cell mimicry of cancer cells and inhibited the gene expression modifications associated with EMT [52].

In the early stages of colorectal neoplasia, it is hypothesized that COX-1 inhibition in platelets by low-dose aspirin may suppress the induction of COX-2/PGE2 in adjacent nucleated cells of the intestinal mucosa [1]. The same mechanism may be applicable to endometrial cancer as endometrial and colorectal cancers have many features in common. Platelet activation induced by chronic inflammation in endometrial cancer might trigger downstream signaling events leading to reduced apoptosis, enhanced cellular proliferation and angiogenesis. The inhibition of platelet activation by low-dose aspirin may indirectly suppress the induction of COX-2 in adjacent nucleated cells of the endometrium during oncogenesis. Therefore, the indirect inhibition of PGE2 biosynthesis combined with inhibition of platelet activation may synergistically suppress tumor progression.

Thrombocytosis is associated with a poor prognosis in many malignancies including endometrial cancer [56,57]. It appears that in ovarian cancer, paraneoplastic thrombocytosis, which is caused by a paracrine circuit of thrombopoietic cytokines from the primary tumor and host tissues, aggressively promotes tumor progression [56]. This process is mediated by hepatic thrombopoietin synthesis that is stimulated by excessive tumor-derived IL-6, and leads to increased numbers and activation of platelets. Increased platelets in turn promote tumor growth, creating a feed-forward loop. Plasma levels of thrombopoietin and IL-6 were significantly elevated in ovarian cancer patients with thrombocytosis as compared with those who did not [56]. Pre-clinical models suggest that indirect reduction in IL-6 by inhibition of platelet activation may have therapeutic potential [56], and a positive relationship between endometrial cancer, which shares some genomic features between uterine serous carcinoma and serous ovarian carcinoma, and IL-6 has been suggested [20,58]. Because paraneoplastic thrombocytosis plays a pivotal role in tumor progression via the IL-6 pathway, indirect suppression of IL-6 by low-dose aspirin may also contribute to anti-tumor effects in endometrial cancer. Thrombocytosis has been shown to be an independent predictor of decreased survival outcome in ovarian clear cell carcinoma, and this pathway warrants further study in clear cell type endometrial cancer [59]. Taken together, a direct inhibition of activated platelet by low-dose aspirin may contribute to suppression of tumor progression.

Preoperative thrombocytosis in women with endometrial cancer is associated with advanced disease and poor disease-specific survival [55]. Mean platelet volume (MPV) is commonly used as one of the parameters of platelet activation in order to evaluate both inflammatory processes and malignancies. Platelets with larger MPV are thought to have granules containing more mediators [60]. MPV and other platelet activation parameters have previously been correlated with the severity of endometrial pathology [61]. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is released by activated platelets, and regulates a variety of cellular processes including cell proliferation, transformation, and migration. It is frequently up-regulated in endometrial cancer, and is associated with aggressive features and poor prognosis [62]. These findings indicate that platelet activation is correlated with the severity of endometrial cancer and precursor lesions and thus, inhibition of platelet activation by low-dose aspirin may contribute importantly to improved survival of patients with endometrial cancer.

6. Relevance of aspirin to molecular pathways and other mechanisms in endometrial cancer

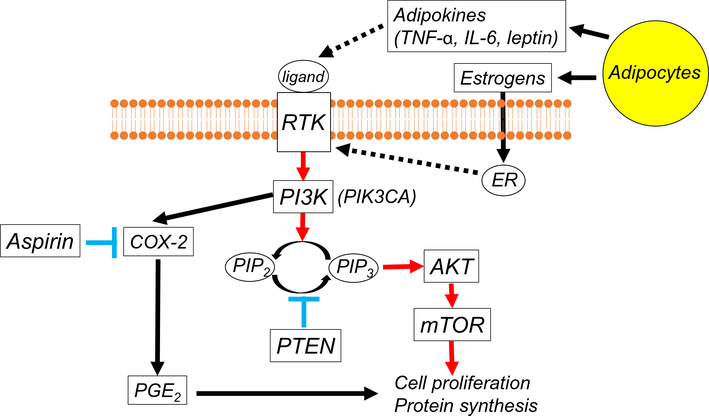

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is frequently hyper-activated in type I endometrial cancer due to the loss of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN [19]. Upregulation of PI3K enhances COX-2 activity and PGE2 synthesis, resulting in proliferation of endometrial cancer cells (Fig. 5) [25]. In a study of colorectal cancer, regular aspirin users had significantly improved overall and disease-specific survival compared to non-users if tumors carried the PIK3CA mutation [63]. Although in vitro aspirin may induce apoptosis through blockade of the PI3K pathway in colorectal cancer [63], the effective concentration of aspirin required to inhibit this pathway is higher than that achieved in vivo with daily low-dose aspirin treatment. Inhibition of platelet activation by low-dose aspirin may indirectly suppress upregulated PGE2 production in endometrial cancer cells. There is currently no study examining an association of PIK3CA mutation and aspirin effects in endometrial cancer, and further study is warranted to see if aspirin use has survival benefits in this population. Given that large fractions of women with endometrial cancer may potentially have an alteration in this pathway, examining the association of aspirin and PIK3CA mutation has a clinical relevance.

Fig. 5.

Aspirin and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in endometrial cancer. The activation of RTK induced by adipokines leads to activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in endometrial cancer. The direct association between ER and RTK also stimulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. The PIK3CA mutations activate the kinase activity of PI3K, which is antagonized by PTEN through its phosphatase function. Up-regulation of PI3K enhances COX-2 activity and PGE2 synthesis in the setting of obesity. Thus, suppression of PGE2 production as would theoretically be achieved with use of aspirin, could be a promising strategy for the treatment of endometrial cancer. Dashed lines represent the suggested pathways in endometrial cancer. Abbreviations: RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; PG, prostaglandin; COX, cyclooxygenase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIK3CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-6, interleukin-6; ER, estrogen receptor; and PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog.

Mucins produced by cancer cells play a critical role in the initial induction of COX-2/PGE2 in the tumor microenvironment. In endometrial cancer patients, tumor-produced mucins are associated with COX-2 induction and immune-suppression [64]. Indirect inhibition of PGE2 by low-dose aspirin may disrupt this feed-forward loop.

TP53 normally suppresses the COX2/PGE2 pathway and is frequently mutated in type II endometrial cancer, leading to a loss of inhibition of this pathway and promotion of tumor growth [19]. In vitro, aspirin at 100 μM demonstrated an anti-cancer effect in breast cancer cells through acetylation of p53, leading to an increase of the protein involved in cell cycle arrest and promotion of apoptosis [39]. A concentration of 100 μM may be more likely to be physiologically achievable compared with that required to inhibit other COX-independent pathways. This pathway may explain the finding that concurrent use of a statin and aspirin improved survival with type II endometrial cancer [65].

Similar to colorectal cancer, mismatch repair (MMR) instability is a frequent molecular finding in endometrial cancer specimens. MMR instability can either originate in the germline, as found in Lynch syndrome, or be somatically acquired and expressed in tumor cells. Functionally, aspirin at millimolar concentrations increased MMR proteins and induced subsequent growth inhibition and apoptosis in MMR-proficient colon cancer cells through COX-independent mechanisms [37]. Aspirin also induces growth inhibition and apoptosis of MMR-deficient colon cancer cells [37]. Thus, it appears that aspirin at millimolar concentrations can inhibit endometrial cancer cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis and changes in the cell cycle, independent of changes in MMR gene expression [66].

Radiation therapy is frequently used as an adjuvant treatment in endometrial cancer. Notably, in our previous study, low-dose aspirin use was associated with improved survival in a subgroup of women who received post-operative whole pelvis radiotherapy [67]. Radiation exposure induces inflammatory changes in the healthy tissues within the radiated field, and such inflammatory changes can therefore cause pro-inflammatory cytokine production that leads to PGE2-driven tumor progression. In this setting, low-dose aspirin may indirectly inhibit the production of PGE2, and block this mechanism of tumor progression as demonstrated in cervical cancer cell lines [68]. Inhibition of TXA2, a vasoconstrictor, as well as inhibition of platelet activation leads to an increase in blood flow and may improve oxygen delivery to the potentially hypoxic tumor cells [69]. This may in turn lead to enhanced generation of radiation-induced reactive oxygen species and may account for the improved outcomes in prostate cancer patients receiving radiation therapy [70].

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), differentiated forms of circulating monocytes in the tissue, appear to be a key mediator of the interaction between host immune cells and cancer cells, and increased accumulation of TAMs in uterine tumors has been demonstrated to be associated with aggressive tumor behaviors and decreased survival outcome of endometrial cancer patients [71,72]. TAMs, once differentiated into polarized M2 macrophages that are a source and target of multiple inflammatory factors, contribute to cancer progression and suppression of anti-tumor immune system [71]. Low-dose aspirin inhibits tumor progression by reducing the number of tumor-associated immune cells including TAMs in neuroblastoma models [73]. There is currently no study investigating an association of aspirin effect and TAMs in endometrial cancer, and further study is warranted to examine this association.

7. Aspirin and endometrial cancer risk

Aspirin and other NSAIDs have been shown to have a clear chemo-preventive effect in colorectal cancer, and there is growing evidence that it functions similarly in other cancers, although risk-benefit profiles remain as yet undetermined [40]. Other malignancies in which there is growing evidence of a beneficial effect of aspirin include other gastrointestinal, breast, lung and prostate cancers [33,74,75]. Randomised control trials (RCTs) have shown that the protective effect of aspirin on the risk of colorectal cancer was greatest in patients after 5 years of aspirin treatment [4]. Other studies confirm that colorectal cancer-specific benefits require a prolonged duration of use from 5 to 10 years [3,40].

Notably, findings of chemo-preventive benefits of aspirin on even colorectal cancer are equivocal when data on women are examined. In six trials of daily low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of vascular events, 3 years of aspirin in women demonstrated a reduction in cancer incidence including uterine tumors [75]. In addition, aspirin reduced the 20-year risk of any fatal colorectal cancer after 5 years of scheduled treatment with 75–300 mg daily dose. No further benefit was demonstrated with doses of aspirin >75 mg daily [4]. However, important to note in interpreting these meta-analyses is that the number of women in the pooled analyses were limited. Additionally, the outcome examined (i.e., mortality secondary to malignancy) is compromised by the inevitable influence of incidence on long-term prospective analyses. Contrary to these findings, results of the large-scale, long-term Women’s Health Study, the only chemo-prevention trial performed exclusively in women, showed no effect of 100 mg alternate-day dosing of aspirin contrasted against placebo on total cancer incidence after a mean duration of 10.1 years [76]. An observational follow-up of the same cohort did show a significant reduction in colorectal cancer after an additional 10 years [77].

Results from observational studies of aspirin and endometrial cancer risk are conflicting. Aspirin has been identified as a potential agent to marginally decrease the risk of endometrial cancer and appears particularly effective in nulliparous and obese patients [33,78–80]. Several studies have specifically examined dosage and frequency of use in addition to duration in relation to endometrial cancer, including our studies [67,81]. In contrast to colorectal cancer where no clear dose-response relationship has been elucidated, an inverse association between aspirin dosage and endometrial cancer incidence has been demonstrated [81]. MMR gene defects (either in germ line or somatic) are a common abnormality in endometrial cancer [19], and a study of patients with these defects reported a large reduction in endometrial cancer incidence with 600 mg aspirin daily [82]. Further investigation to evaluate the chemo-preventive effect of aspirin on endometrial cancer within specific populations may be warranted.

8. Aspirin and cancer mortality

Prospective studies (i.e., cohorts or trials) that examine cancer mortality conditioned on incidence are by design limited in their interpretation, as it can be unclear whether an agent associated with reduced mortality implies a reduction in incidence, improvement in survival, or both. There has been few studies examined the dose-dependent effect of aspirin on cancer mortality in various malignancies [4–6,74,75]; although it has been examined in more detail in some studies of endometrial cancer [81,83]. Some have demonstrated that reductions in cancer deaths became apparent after 5 years of treatment, and that the beneficial effects increased with over 20 years of treatment [6,74]. Overall, aspirin reduced cancer deaths by 20%, particularly after 5 years of treatment by 40% [75]. The improved carcinoma mortality with daily aspirin was seen more rapidly than the reduction in the incidence of some of these carcinomas [5,74,75]. This suggests that aspirin acts to reduce the growth and metastasis of these cancers. Aspirin may have a larger effect on adenocarcinomas than on non-adenocarcinoma in solid tumors [5,6]. A prior RCT has shown that the benefit of daily aspirin on lung and esophageal cancer death was confined to adenocarcinomas and the overall benefit on 20-year risk of cancer death was greatest for adenocarcinomas [6]. An overall decreased mortality rate was seen in adenocarcinoma patients receiving treatment, particularly in those without metastasis at diagnosis [5]. These findings may indicate that aspirin improves survival in patients with adenocarcinoma by preventing distant metastasis. Other RCTs showed that this reduced mortality rate due to cancer was unrelated to the dose of aspirin used (75 mg upwards) [4,6]. These findings also indicate that the primary mechanism for the benefits of aspirin for cancer treatment likely involve platelet inactivation, and thus a high dose of aspirin may not be necessary for improved cancer survival.

9. Aspirin and endometrial cancer-specific survival

At present, only four studies have examined the association between aspirin use and cause-specific survival among endometrial cancer patients (Table 1) [65,67,83,84]. A study by Nevadunsky et al. found that use of aspirin in conjunction with a statin was associated with improved survival from non-endometrioid endometrial cancer histologic subtypes (type II) [hazard ratio (HR) 0.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.09–0.70] [65]. Our study reported an association of low-dose aspirin with improved survival outcomes in endometrial adenocarcinoma patients (disease-specific mortality: HR 0.23, 95% CI 0.08–0.64); improved survival was particularly noted in subgroups of women that were young, obese, had low-grade disease, and those that had received postoperative radiotherapy [67]. Contrary to low-dose aspirin use, other NSAIDs use was associated with increased risk of endometrial cancer recurrence and mortality [67]. We also reported results from a recent large-scale nation-wide prospective study (GOG-210) that use of NSAIDs, including aspirin individually, was associated with increased endometrial carcinoma-specific mortality, especially in patients with type I tumors [83]. Specifically, women who used aspirin/NSAIDs for >10 years prior to diagnosis were found to have an approximately two-fold increased risk of endometrial carcinoma-specific mortality relative to non-users (HR 1.92, 95% CI 1.20–3.08). Sanni et al. recently published a large prospective cohort study from the United Kingdom analyzing the impact of low-dose aspirin use following a diagnosis of endometrial cancer on endometrial cancer specific survival. This study found no association between low-dose aspirin use and endometrial cancer specific survival (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.69–1.20) [84].

Table 1.

Studies of aspirin use and endometrial cancer survival.a

| Characteristics | Nevadunsky et al. [65] | Matsuo et al. [67] | Brasky et al. [83] | Sanni et al. [84] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2017 |

| Sample size | n = 983 | n = 1687 | n = 4609 | n = 3058 |

| Site | New York | California/Japan | 62 sites in US | United Kingdom |

| Aspirin definition | N/A | Low-dose (81–100 mg) | Any dose, ≥1 day/week for ≥1 year | Low-dose (81–100 mg) |

| Aspirin use | 15.9% | 9.4% | 41% | 23.5% |

| Aspirin effect | Favor for type II | Favor for type I | Adverse effects in type I | No significant effect |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.25 (0.09–0.70) | 0.23 (0.08–0.64) | 1.92 (1.20–3.08) | 0.91 (0.69–1.20) |

| Age (years)c | 62.7/67.7d | 56 | 23–92 | 70.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean) | 33.1/29.6d | 30.2 | 31.1 | Stratified analysis by BMI |

| Race | (White 39%/Black 31%)b | Asian 54%, Hispanic 34% | White 84% | N/A |

| Black 11.6% | ||||

| Other 3.6% | ||||

| Diabetes | 25.5% | 21.8% | 21.6% | N/A |

| Endometrioid | (60.2%)b | 84.2% | 73.6% | N/A |

| High-grade | 44.9% | 21.5% | 39.7% | 17% |

| Stage IV | 9.7% | 6.5% | 4.4% | 1% |

| Definition of type I cancer | Grade 1–3 endometrioid | Grade 1–2 endometrioid | Grade 1–3 endometrioid | No distinction between type I and II |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; and N/A, not available.

Adopted and modified from reference [67].

Original paper did not have information, and author’s recent paper was used to estimate the number.

Median, mean, or range.

Censored cases and died of endometrial cancer cases, respectively.

Each of these studies was performed in different patient populations with different tumor characteristics; thus complicating their comparison. For example, our study on low-dose aspirin included a younger population, which was split between Japan and the United States, and there was more endometrioid histology, early-stage disease, and low-grade tumors than the other study groups [67]. It is well established that risk and mortality outcomes for endometrial cancer vary among racial subgroups [85]. Table 1 also includes a summary of racial background for the respective study populations. Clearly, more research into endometrial cancer elaborating effects aspirin dose and frequency on specific populations and histologies needs to be done before conclusive therapeutic recommendations can be made. In addition, NSAIDs other than aspirin are often used as analgesia.

10. Harms and overall benefits of aspirin

Aspirin use is associated with an increased risk of bleeding complications. Meta-analysis has indicated that aspirin (75–325 mg/day) use resulted in an approximately 1.7-fold increase in the risk of major bleeding including both intra-cranial and from the gastro-intestinal tract [86]. However, the absolute increase was modest, as 769 patients needed to be treated with aspirin to cause one additional major bleeding episode annually [86]. Other studies of aspirin for primary and secondary prevention of CVDs showed a significant reduction in serious vascular events with a non-significant increase in hemorrhagic stroke [2]. Moreover, the risk of bleeding with aspirin use is dose dependent, with low-dose aspirin posing a lower risk than the regular dose. To maximize benefit over hazard in the treatment of endometrial cancer, co-prescription of a proton-pump inhibitor, screening for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, and eradication of H. pylori infection before starting aspirin may be effective in reducing the incidence of gastro-intestinal bleeding. The presence of H. pylori infection is one of the major risk factors for gastro-intestinal complications and H. pylori eradication therapy is effective in preventing these complications [87]. It is also important to note that the risk of bleeding is highest during the first few months of aspirin use [88]. Careful assessment of risk factors and monitoring for early bleeding episodes as well as their timely treatment may reduce aspirin-related harms. Reducing risk of thromboembolic events may be another benefit of aspirin [89]. In particular, certain populations of women with endometrial cancer carry a disproportionally increased risk of venous thromboembolism that may have potential benefit from aspirin taking for prevention [90].

New products have been developed to overcome some of the potential toxicities of traditional aspirin. Aspirin-phosphatidylcholine (PC), in which aspirin is formulated with PC-enriched soy lecithin and has been awarded a new drug approval (NDA, #203697) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States, not only has improved gastro-intestinal safety profiles but also maintained an anti-neoplastic function [91,92]. The use of aspirin-PC may lower the potential risk of bleeding complications.

Both endometrial cancer and CVDs share many risk factors. Endometrial cancer is strongly correlated with obesity, which is also associated with hypertension and CVDs [93]. Hypertension is the major risk factor for hemorrhagic stroke and these tend to occur mainly in individuals with inadequately treated hypertension. As our study showed, patients with endometrial cancer are more likely to suffer from this comorbidity (40.4%) [67]. It has been shown that low-dose aspirin together with anti-hypertensive drugs significantly reduced major CVDs, while there was no effect on the incidence of stroke or fatal bleeds. Non-fatal major bleeds were twice as common [94]. Ensuring adequate blood pressure control prior to starting aspirin and during aspirin use can minimize this harm. Endometrial cancer patients continue to die of their obesity-related comorbidities including CVDs and diabetes mellitus more than endometrial cancer [10]. Although the evidence is currently conflicting, the potential for a therapeutic effect of low-dose aspirin in women with endometrial cancer could be considered to be greater than the potential harm from aspirin-related bleeding.

Although not yet studied specifically in women with endometrial cancer, data in other malignancies has shown that aspirin initiation is well tolerated in cancer survivors. Furthermore, not only is aspirin tolerated post-diagnosis, but reduction in both all-cause and colorectal cancer-specific mortality has been noted with aspirin use even when initiated following malignancy diagnosis [95,96]. In an analysis of compliance trends among patients with breast and colorectal cancer, it was noted that the probability of continuing prescribed aspirin declined in the 24 months approaching death, but the decision making behind the cessation of aspirin was not explored [97].

In addition, although we have discussed multiple mechanisms via which aspirin is hypothesized to have beneficial effects on oncogenesis of inflammatory tumors, there are also mechanistic insights that potentially explain some of the results showing null or harmful effects of aspirin on endometrial cancer outcomes. Notably, a particular aspirin-triggered lipoxin (ATL), known as LXA4, has been shown to act as an estrogenic substance and has been demonstrated to have in vitro and clinical estrogenic activity on estrogen-responsive endometrial epithelial cell lines [98]. The mitogenic effects of ATL were comparable to those of estradiol on estrogen receptors in murine models [98]. This relatively recently elaborated mechanism still requires further investigation; however, it is an example of an unexpected physiologic effect that could underlie the conflicting data on aspirin in endometrial adenocarcinoma that is accumulating.

11. Conclusion

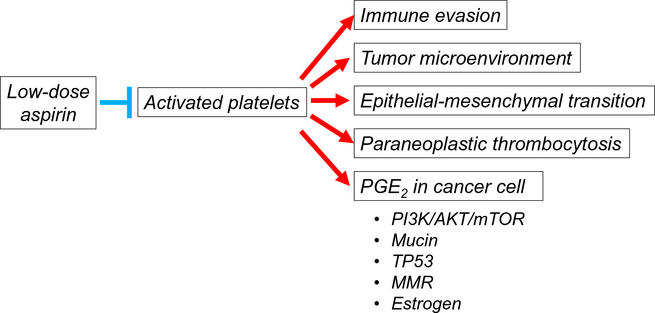

Endometrial cancer is an increasing threat due to the growing prevalence of obesity. Evidence from pre-clinical and clinical studies indicates that aspirin has the potential to improve survival of endometrial cancer through inhibition of activated platelets (Fig. 6). In addition, initiation on aspirin may be of benefit for the obesity-related comorbidities seen in endometrial cancer patients. Although aspirin-related bleeding has to be considered prior to therapy, in most cases, the benefits of low-dose aspirin therapy substantially will exceed the risk. Since the direct evidence to show the benefit of low-dose aspirin on endometrial cancer is scarce, and there is some evidence showing potential increased risk in endometrial cancer outcomes, future studies will be warranted to provide more evidence in this area.

Fig. 6.

Low-dose aspirin: proposed anti-tumor mechanisms in endometrial cancer. Activated platelets are integral to the process of metastasis. Low-dose aspirin treatment inhibits activation of platelet, leading to suppression of tumor-promoting mechanisms. Increase in PGE2 is strongly associated with several pathways which contribute to endometrial cancer progression. Low-dose aspirin treatment may suppress endometrial cancer progression by inhibition of activated platelet. Abbreviations: PG, prostaglandin; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; and MMR, mismatch repair.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Aspirin has been shown to have chemo-preventive effects on colorectal cancer.

Aspirin can suppress platelet activation.

Aspirin can indirectly inhibit prostaglandin E2, an obesity-related inflammatory marker.

Aspirin may improve the survival of women with endometrial adenocarcinoma.

Effects of aspirin on endometrial cancer risk and survival is conflicting.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Brendan H. Grubbs for scientific review of the manuscript.

Funding support: Ensign Endowment for Gynecologic Cancer Research (K.M.), the American Cancer Society Research Professor Award (A.K.S.), and the Frank McGraw Memorial Chair in Cancer Research (A.K.S.).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest in all the authors.

References

- [1].Patrignani P, Patrono C, Aspirin and cancer, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68 (2016) 967–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P, Meade T, Patrono C, Roncaglioni MC, Zanchetti A, Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials, Lancet 373 (2009) 1849–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bibbins-Domingo K, Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement, Ann. Intern. Med. 164 (2016) 836–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Elwin CE, Norrving B, Algra A, Warlow CP, Meade TW, Long-term effect of aspirin on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: 20-year follow-up of five randomised trials, Lancet 376 (2010) 1741–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Price JF, Belch JF, Meade TW, Mehta Z, Effect of daily aspirin on risk of cancer metastasis: a study of incident cancers during randomised controlled trials, Lancet 379 (2012) 1591–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rothwell PM, Fowkes FG, Belch JF, Ogawa H, Warlow CP, Meade TW, Effect of daily aspirin on long-term risk of death due to cancer: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials, Lancet 377 (2011) 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Umar A, Steele VE, Menter DG, Hawk ET, Mechanisms of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in cancer prevention, Semin. Oncol. 43 (2016) 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].The Surveillance E, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute, http://seercancergov/statfacts/html/corphtml 2016, Accessed date: 2 November 2016.

- [9].Felix AS, Scott McMeekin D, Mutch D, Walker JL, Creasman WT, Cohn DE, Ali S, Moore RG, Downs LS, Ioffe OB, Park KJ, Sherman ME, Brinton LA, Associations between etiologic factors and mortality after endometrial cancer diagnosis: the NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group 210 trial, Gynecol. Oncol. 139 (2015) 70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Papatla K, Huang M, Slomovitz B, The obese endometrial cancer patient: how do we effectively improve morbidity and mortality in this patient population? Ann. Oncol. 27 (2016) 1988–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schmandt RE, Iglesias DA, Co NN, Lu KH, Understanding obesity and endometrial cancer risk: opportunities for prevention, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 205 (2011) 518–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McAlpine JN, Temkin SM, Mackay HJ, Endometrial cancer: not your grandmother’s cancer, Cancer 122 (2016) 2787–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bokhman JV, Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma, Gynecol. Oncol. 15 (1983) 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC, McCann SE, Yu H, Xiang YB, Wolk A, Wentzensen N, Weiss NS, Webb PM, van den Brandt PA, van de Vijver K, Thompson PJ, Strom BL, Spurdle AB, Soslow RA, Shu XO, Schairer C, Sacerdote C, Rohan TE, Robien K, Risch HA, Ricceri F, Rebbeck TR, Rastogi R, Prescott J, Polidoro S, Park Y, Olson SH, Moysich KB, Miller AB, McCullough ML, Matsuno RK, Magliocco AM, Lurie G, Lu L, Lissowska J, Liang X, Lacey JV Jr., Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Hankinson SE, Hakansson N, Goodman MT, Gaudet MM, Garcia-Closas M, Friedenreich CM, Freudenheim JL, Doherty J, De Vivo I, Courneya KS, Cook LS, Chen C, Cerhan JR, Cai H, Brinton LA, Bernstein L, Anderson KE, Anton-Culver H, Schouten LJ, Horn-Ross PL, Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J. Clin. Oncol. 31 (2013) 2607–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP, Colorectal cancer, Lancet 383 (2014) 1490–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ, Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults, N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (2003) 1625–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nieman KM, Romero IL, Van Houten B, Lengyel E, Adipose tissue and adipocytes support tumorigenesis and metastasis, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831 (2013) 1533–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shaw E, Farris M, McNeil J, Friedenreich C, Obesity and endometrial cancer, Recent Results Cancer Res. 208 (2016) 107–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].A Merritt M, Cramer DW, Molecular pathogenesis of endometrial and ovarian cancer, Cancer Biomark 9 (2010) 287–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Che Q, Liu BY, Liao Y, Zhang HJ, Yang TT, He YY, Xia YH, Lu W, He XY, Chen Z, Wang FY, Wan XP, Activation of a positive feedback loop involving IL-6 and aromatase promotes intratumoral 17beta-estradiol biosynthesis in endometrial carcinoma microenvironment, Int. J. Cancer 135 (2014) 282–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Harvey AE, Lashinger LM, Hursting SD, The growing challenge of obesity and cancer: an inflammatory issue, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1229 (2011) 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Friedenreich CM, Langley AR, Speidel TP, Lau DC, Courneya KS, I. Csizmadi, A.M. Magliocco, Y. Yasui, L.S. Cook, Case-control study of inflammatory markers and the risk of endometrial cancer, Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 22 (2013) 374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang T, Rohan TE, Gunter MJ, Xue X, Wactawski-Wende J, Rajpathak SN, Cushman M, Strickler HD, Kaplan RC, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Scherer PE, Ho GYA, Prospective study of inflammation markers and endometrial cancer risk in post-menopausal hormone nonusers, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 20 (2011) 971–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Skandalis SS, Afratis N, Smirlaki G, Nikitovic D, Theocharis AD, Tzanakakis GN, Karamanos NK, Cross-talk between estradiol receptor and EGFR/IGF-IR signaling pathways in estrogen-responsive breast cancers: focus on the role and impact of proteoglycans, Matrix Biol. 35 (2013) 182–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gao J, Tian J, Lv Y, Shi F, Kong F, Shi H, Zhao L, Leptin induces functional activation of cyclooxygenase-2 through JAK2/STAT3, MAPK/ERK, and PI3K/AKT pathways in human endometrial cancer cells, Cancer Sci. 100 (2009) 389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Thorat MA, Cuzick J, Role of aspirin in cancer prevention, Curr. Oncol. Rep. 15 (2013) 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pedersen AK, GA FitzGerald, Dose-related kinetics of aspirin. Presystemic acetylation of platelet cyclooxygenase, N. Engl. J. Med. 311 (1984) 1206–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Levy BD, Clish CB, Schmidt B, Gronert K, Serhan CN, Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: signals in resolution, Nat. Immunol. 2 (2001) 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Romano M, Cianci E, Simiele F, Recchiuti A, Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxins in resolution of inflammation, Eur. J. Pharmacol. 760 (2015) 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chiang N, Bermudez EA, Ridker PM, Hurwitz S, Serhan CN, Aspirin triggers antiinflammatory 15-epi-lipoxin A4 and inhibits thromboxane in a randomized human trial, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 (2004) 15178–15183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dovizio M, Bruno A, Tacconelli S, Patrignani P, Mode of action of aspirin as a chemopreventive agent, Recent Results Cancer Res. 191 (2013) 39–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Patrignani P, Tacconelli S, Piazuelo E, Di Francesco L, Dovizio M, Sostres C, Marcantoni E, Guillem-Llobat P, Del Boccio P, Zucchelli M, Patrono C, Lanas A, Reappraisal of the clinical pharmacology of low-dose aspirin by comparing novel direct and traditional indirect biomarkers of drug action, J. Thromb. Haemost. 12 (2014) 1320–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Verdoodt F, Friis S, Dehlendorff C, Albieri V, Kjaer SK, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, Gynecol. Oncol. 140 (2016) 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Thun MJ, Jacobs EJ, Patrono C, The role of aspirin in cancer prevention, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 9 (2012) 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Boutaud O, Sosa IR, Amin T, Oram D, Adler D, Hwang HS, Crews BC, Milne G, Harris BK, Hoeksema M, Knollmann BC, Lammers PE, Marnett LJ, Massion PP, Oates JA, Inhibition of the biosynthesis of prostaglandin E2 by low-dose aspirin: implications for adenocarcinoma metastasis, Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 9 (2016) 855–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sciulli MG, Filabozzi P, Tacconelli S, Padovano R, Ricciotti E, Capone ML, Grana M, Carnevale V, Patrignani P, Platelet activation in patients with colorectal cancer, Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 72 (2005) 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Goel A, Chang DK, Ricciardiello L, Gasche C, Boland CR, A novel mechanism for aspirin-mediated growth inhibition of human colon cancer cells, Clin. Cancer Res. 9 (2003) 383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS, Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in relation to the expression of COX-2, N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (2007) 2131–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Alfonso LF, Srivenugopal KS, Arumugam TV, Abbruscato TJ, Weidanz JA, Bhat GJ, Aspirin inhibits camptothecin-induced p21CIP1 levels and potentiates apoptosis in human breast cancer cells, Int. J. Oncol. 34 (2009) 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cuzick J, Otto F, Baron JA, Brown PH, Burn J, Greenwald P, Jankowski J, La Vecchia C, Meyskens F, Senn HJ, Thun M, Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for cancer prevention: an international consensus statement, Lancet Oncol. 10 (2009) 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].A Arango H, Icely S, Roberts WS, Cavanagh D, Becker JL, Aspirin effects on endometrial cancer cell growth, Obstet. Gynecol. 97 (2001) 423–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang D, Dubois RN, Eicosanoids and cancer, Nat. Rev. Cancer 10 (2010) 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jabbour HN, Milne SA, Williams AR, Anderson RA, Boddy SC, Expression of COX-2 and PGE synthase and synthesis of PGE(2)in endometrial adenocarcinoma: a possible autocrine/paracrine regulation of neoplastic cell function via EP2/EP4 receptors, Br. J. Cancer 85 (2001) 1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Frasor J, Weaver AE, Pradhan M, Mehta K, Synergistic up-regulation of prostaglandin E synthase expression in breast cancer cells by 17beta-estradiol and proinflammatory cytokines, Endocrinology 149 (2008) 6272–6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tamura M, Sebastian S, Yang S, Gurates B, Ferrer K, Sasano H, Okamura K, Bulun SE, Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin synthesis in endometrial stromal cells by malignant endometrial epithelial cells. A paracrine effect mediated by prostaglandin E2 and nuclear factor-kappa B, J. Biol. Chem. 277 (2002) 26208–26216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsuji S, Sawaoka H, Hori M, DuBois RN, Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells, Cell 93 (1998) 705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ke J, Yang Y, Che Q, Jiang F, Wang H, Chen Z, Zhu M, Tong H, Zhang H, Yan X, Wang X, Wang F, Liu Y, Dai C, Wan X, Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) promotes proliferation and invasion by enhancing SUMO-1 activity via EP4 receptor in endometrial cancer, Tumour Biol. 37 (2016) 12203–12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lambropoulou M, Alexiadis G, Limberis V, Nikolettos N, Tripsianis G, Clinicopathologic and prognostic significance of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in endometrial carcinoma, Histol. Histopathol. 20 (2005) 753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sales KJ, Battersby S, Williams AR, H.N. RA Anderson, Jabbour, Prostaglandin E2 mediates phosphorylation and down-regulation of the tuberous sclerosis-2 tumor suppressor (tuberin) in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells via the Akt signaling pathway,J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (2004) 6112–6118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhao Y, Agarwal VR, Mendelson CR, Simpson ER, Estrogen biosynthesis proximal to a breast tumor is stimulated by PGE2 via cyclic AMP, leading to activation of promoter II of the CYP19 (aromatase) gene, Endocrinology 137 (1996. ) 5739–5742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Jarzabek K, Koda M, Walentowicz-Sadlecka M, Grabiec M, Laudanski P, Wolczynski S, Altered expression of ERs, aromatase, and COX2 connected to estrogen action in type I endometrial cancer biology, Tumour Biol. 34 (2013) 4007–4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Guillem-Llobat P, Dovizio M, Bruno A, Ricciotti E, Cufino V, Sacco A, Grande R, Alberti S, Arena V, Cirillo M, Patrono C, FitzGerald GA, Steinhilber D, Sgambato A, Patrignani P, Aspirin prevents colorectal cancer metastasis in mice by splitting the crosstalk between platelets and tumor cells, Oncotarget 7 (2016) 32462–32477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dovizio M, Maier TJ, Alberti S, Di Francesco L, Marcantoni E, Munch G, John CM, Suess B, Sgambato A, Steinhilber D, Patrignani P, Pharmacological inhibition of platelet-tumor cell cross-talk prevents platelet-induced overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in HT29 human colon carcinoma cells, Mol. Pharmacol. 84 (2013) 25–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Murphey LJ, Williams MK, Sanchez SC, Byrne LM, Csiki I, Oates JA, Johnson DH, Morrow JD, Quantification of the major urinary metabolite of PGE2 by a liquid chromatographic/mass spectrometric assay: determination of cyclooxygenase-specific PGE2 synthesis in healthy humans and those with lung cancer, Anal. Biochem. 334 (2004) 266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jurasz P, Alonso-Escolano D, Radomski MW, Platelet-cancer interactions: mechanisms and pharmacology of tumour cell-induced platelet aggregation, Br. J. Pharmacol. 143 (2004) 819–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Stone RL, Nick AM, McNeish IA, Balkwill F, Han HD, Bottsford-Miller J, Rupairmoole R, Armaiz-Pena GN, Pecot CV, Coward J, Deavers MT, Vasquez HG, Urbauer D, Landen CN, Hu W, Gershenson H, Matsuo K, Shahzad MM, King ER, Tekedereli I, Ozpolat B, Ahn EH, Bond VK, Wang R, Drew AF, Gushiken F, Lamkin D, Collins K, DeGeest K, Lutgendorf SK, Chiu W, Lopez-Berestein G, Afshar-Kharghan V, Sood AK, Paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in ovarian cancer, N. Engl. J. Med. 366 (2012) 610–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Njolstad TS, Engerud H, Werner HM, Salvesen HB, Trovik J, Preoperative anemia, leukocytosis and thrombocytosis identify aggressive endometrial carcinomas, Gynecol. Oncol. 131 (2013) 410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, Robertson AG, Pashtan I, Shen R, Benz CC, Yau C, Laird PW, Ding L, Zhang W, Mills GB, Kucherlapati R, Mardis ER, Levine DA, Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma, Nature 497 (2013) 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Matsuo K, Hasegawa K, Yoshino K, Murakami R, Hisamatsu T, Stone RL, Previs RA, Hansen JM, Ikeda Y, Miyara A, Hiramatsu K, Enomoto T, Fujiwara K, Matsumura N, Konishi I, Roman LD, Gabra H, Fotopoulou C, Sood AK, Venous thromboembolism, interleukin-6 and survival outcomes in patients with advanced ovarian clear cell carcinoma, Eur. J. Cancer 51 (2015) 1978–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Park Y, Schoene N, Harris W, Mean platelet volume as an indicator of platelet activation: methodological issues, Platelets 13 (2002) 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Karateke A, Kaplanoglu M, Baloglu A, Relations of platelet indices with endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 16 (2015) 4905–4908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ding J, Li XM, Liu SL, Zhang Y, Li T, Overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor-D as a poor prognosticator in endometrial cancer, Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 15 (2014) 3741–3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Baba Y, Shima K, Sun R, Nosho K, Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Chan AT, Ogino S, Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival, N. Engl. J. Med. 367 (2012) 1596–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ohno S, Ohno Y, Nakada H, Suzuki N, Soma G, Inoue M, Expression of Tn and sialyl-Tn antigens in endometrial cancer: its relationship with tumor-produced cyclooxygenase-2, tumor-infiltrated lymphocytes and patient prognosis, Anticancer Res. 26 (2006) 4047–4053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Nevadunsky NS, Van Arsdale A, Strickler HD, Spoozak LA, Moadel A, Kaur G, Girda E, Goldberg GL, Einstein MH, Association between statin use and endometrial cancer survival, Obstet. Gynecol. 126 (2015) 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wood NJ, Quinton NA, Burdall S, Sheridan E, Duffy SR, Exploring the potential chemopreventative effect of aspirin and rofecoxib on hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer-like endometrial cancer cells in vitro through mechanisms involving apoptosis, the cell cycle, and mismatch repair gene expression, Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 17 (2007) 447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Matsuo K, Cahoon SS, Yoshihara K, Shida M, Kakuda M, Adachi S, Moeini A, Machida H, Garcia-Sayre J, Ueda Y, Enomoto T, Mikami M, Roman LD, Sood AK, Association of low-dose aspirin and survival of women with endometrial cancer, Obstet. Gynecol. 128 (2016) 127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Jeon YT, Song YC, Kim SH, Wu HG, Kim IH, Park IA, Kim JW, Park NH, Kang SB, Lee HP, Song YS, Influences of cyclooxygenase-1 and −2 expression on the radiosensitivities of human cervical cancer cell lines, Cancer Lett. 256 (2007) 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Goldhaber SZ, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, LaMotte F, Rosner B, Buring JE, Hennekens CH, Low-dose aspirin and subsequent peripheral arterial surgery in the Physicians’ Health Study, Lancet 340 (1992) 143–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Jacobs CD, Chun SG, Yan J, Xie XJ, Pistenmaa DA, Hannan R, Lotan Y, Roehrborn CG, Choe KS, Kim DW, Aspirin improves outcome in high risk prostate cancer patients treated with radiation therapy, Cancer Biol. Ther. 15 (2014) 699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Ugel S, De Sanctis F, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V, Tumor-induced myeloid deviation: when myeloid-derived suppressor cells meet tumor-associated macrophages, J. Clin. Invest. 125 (2015) 3365–3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kubler K, Ayub TH, Weber SK, Zivanovic O, Abramian A, Keyver-Paik MD, Mallmann MR, Kaiser C, Serce NB, Kuhn W, Rudlowski C, Prognostic significance of tumor-associated macrophages in endometrial adenocarcinoma, Gynecol. Oncol. 135 (2014) 176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Carlson LM, Rasmuson A, Idborg H, Segerstrom L, Jakobsson PJ, Sveinbjornsson B, Kogner P, Low-dose aspirin delays an inflammatory tumor progression in vivo in a transgenic mouse model of neuroblastoma, Carcinogenesis 34(2013) 1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Algra AM, Rothwell PM, Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials, Lancet Oncol. 13 (2012) 518–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Rothwell PM, Price JF, Fowkes FG, Zanchetti A, Roncaglioni MC, Tognoni G, Lee R, Belch JF, Wilson M, Mehta Z, Meade TW, Short-term effects of daily aspirin on cancer incidence, mortality, and non-vascular death: analysis of the time course of risks and benefits in 51 randomised controlled trials, Lancet 379 (2012) 1602–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Cook NR, Lee IM, Gaziano JM, Gordon D, Ridker PM, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cancer: the Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial, JAMA 294 (2005) 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Cook NR, Lee IM, Zhang SM, Moorthy MV, Buring JE, Alternate-day, low-dose aspirin and cancer risk: long-term observational follow-up of a randomized trial, Ann. Intern. Med. 159 (2013) 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Brons N, Baandrup L, Dehlendorff C, Kjaer SK, Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of endometrial cancer: a nationwide case-control study, Cancer Causes Control 26 (2015) 973–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Neill AS, Nagle CM, Protani MM, Obermair A, Spurdle AB, Webb PM, Aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol and risk of endometrial cancer: a case-control study, systematic review and meta-analysis, Int. J. Cancer 132 (2013) 1146–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Brasky TM, Cohn DE, Bernardo BM, Aspirin and endometrial cancer risk, Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 17 (2016) 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Brasky TM, Moysich KB, Cohn DE, White E, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and endometrial cancer risk in the VITamins And Lifestyle (VITAL) cohort, Gynecol. Oncol. 128 (2013) 113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Burn J, Gerdes AM, Macrae F, Mecklin JP, Moeslein G, Olschwang S, Eccles D, Evans DG, Maher ER, Bertario L, Bisgaard ML, Dunlop MG, Ho JW, Hodgson SV, Lindblom A, Lubinski J, Morrison PJ, Murday V, Ramesar R, Side L, Scott RJ, Thomas HJ, Vasen HF, Barker G, Crawford G, Elliott F, Movahedi M, Pylvanainen K, Wijnen JT, Fodde R, Lynch HT, Mathers JC, Bishop DT, Long-term effect of aspirin on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial, Lancet 378 (2011) 2081–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Brasky TM, Felix AS, Cohn DE, McMeekin DS, Mutch DG, Creasman WT, Thaker PH, Walker JL, Moore RG, Lele SB, Guntupalli SR, Downs LS, Nagel CI, Boggess JF, Pearl ML, Ioffe OB, Park KJ, Ali S, Brinton LA, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and endometrial carcinoma mortality and recurrence, J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 109 (2017) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Sanni OB, Mc Menamin UC, Cardwell CR, Sharp L, Murray LJ, Coleman HG, Commonly used medications and endometrial cancer survival: a population-based cohort study, Br. J. Cancer 117 (2017) 432–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Fedewa SA, Lerro C, Chase D, Ward EM, Insurance status and racial differences in uterine cancer survival: a study of patients in the National Cancer Database, Gynecol. Oncol. 122 (2011) 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].McQuaid KR, Laine L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of adverse events of low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel in randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Med l2006;119: 624–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Chan FK, To KF, Wu JC, Yung MY, Leung WK, Kwok T, Hui Y, Chan HL, Chan CS, Hui E, Woo J, Sung JJ, Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and risk of peptic ulcers in patients starting long-term treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a randomised trial, Lancet 359 (2002) 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].A Garcia Rodriguez L, Hernandez-Diaz S, de Abajo FJ, Association between aspirin and upper gastrointestinal complications: systematic review of epidemiologic studies, Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52 (2001) 563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Simes J, Becattini C, Agnelli G, Eikelboom JW, Kirby AC, Mister R, Prandoni P, Brighton TA, Aspirin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism: the INSPIRE collaboration, Circulation 130 (2014) 1062–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Matsuo K, Yessaian AA, Lin YG, Pham HQ, Muderspach LI, Liebman HA, Morrow CP, Roman LD, Predictive model of venous thromboembolism in endometrial cancer, Gynecol. Oncol. 128 (2013) 544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Huang Y, Lichtenberger LM, Taylor M, Bottsford-Miller JN, Haemmerle M, Wagner MJ, Lyons Y, Pradeep S, Hu W, Previs RA, Hansen JM, Fang D, Dorniak PL, Filant J, Dial EJ, Shen F, Hatakeyama H, Sood AK, Antitumor and antiangiogenic effects of aspirin-PC in ovarian cancer, Mol. Cancer Ther. 15 (2016) 2894–2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Lim YJ, Dial EJ, Lichtenberger LM, Advent of novel phosphatidylcholine-associated nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with improved gastrointestinal safety, Gut Liver 7 (2013) 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Schmieder RE, Messerli FH, Does obesity influence early target organ damage in hypertensive patients? Circulation 87 (1993) 1482–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlof B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, Menard J, Rahn KH, Wedel H, Westerling S, Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group, Lancet 351 (1998) 1755–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].McCowan C, Munro AJ, Donnan PT, Steele RJ, Use of aspirin post-diagnosis in a cohort of patients with colorectal cancer and its association with all-cause and colorectal cancer specific mortality, Eur. J. Cancer 49 (2013) 1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Li P, Wu H, Zhang H, Shi Y, Xu J, Ye Y, Xia D, Yang J, Cai J, Wu Y, Aspirin use after diagnosis but not prediagnosis improves established colorectal cancer survival: a meta-analysis, Gut 64 (2015) 1419–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Murphy L, Brown C, Smith A, Cranfield F, Sharp L, Visvanathan K, Bennett K, Barron TI, End-of-life prescribing of aspirin in patients with breast or colorectal cancer, BMJ Support. Palliat. Care (2017) in-press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Russell R, Gori I, Pellegrini C, Kumar R, Achtari C, Canny GO, Lipoxin A4 is a novel estrogen receptor modulator, FASEB J. 25 (2011) 4326–4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]