MacroD2, a human macrodomain protein with mono-ADP-ribosyl-hydrolyzing activity, is a single-domain protein containing a deep ADP-ribose-binding groove. Three crystal structures of human MacroD2 in the apo state, in different space groups, were determined at between 1.7 and 1.9 Å resolution. Comparison with a previous crystal structure of MacroD2 in complex with ADP-ribose revealed conformational changes in side chains, potentially facilitating design efforts of a MacroD2 inhibitor.

Keywords: macrodomain, ADP-ribosylation, ADP-ribosyl-hydrolase, crystal forms, apo structure

Abstract

MacroD2 is one of the three human macrodomain proteins characterized by their protein-linked mono-ADP-ribosyl-hydrolyzing activity. MacroD2 is a single-domain protein that contains a deep ADP-ribose-binding groove. In this study, new crystallization conditions for MacroD2 were found and three crystal structures of human MacroD2 in the apo state were solved in space groups P41212, P43212 and P43, and refined at 1.75, 1.90 and 1.70 Å resolution, respectively. Structural comparison of the apo crystal structures with the previously reported crystal structure of MacroD2 in complex with ADP-ribose revealed conformational changes in the side chains of Val101, Ile189 and Phe224 induced by the binding of ADP-ribose in the active site. These conformational variations may potentially facilitate design efforts of a MacroD2 inhibitor.

1. Introduction

Macrodomains are either conserved structural domains that are found in larger proteins or self-standing domains, and consist of a fold comprising mixed α-helices and β-sheets (Rack et al., 2016 ▸). There are two major classes of these enzymes, which are referred to as ADP-ribosylation erasers and binders. Erasers, which are also known as hydrolyzing macrodomains, remove poly-ADP-ribose (PAR) or mono-ADP-ribose (MAR) from the target protein and regulate enzymatic activities in various cellular pathways. Binders or recognizing macrodomains do not hydrolyze the modification, but rather just bind ADP-ribose (ADPr) and affect protein–protein interactions (Rosenthal et al., 2013 ▸).

Three human macrodomain proteins, MacroD1, MacroD2 and TARG1, are known to be able to hydrolyze terminal ADPr linked to glutamate/aspartate residues. In addition, they can hydrolyze O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (OAADPr) and other nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) metabolites to generate free ADPr (Chen et al., 2011 ▸). Subsequently, it has been shown that MacroD2 can also hydrolyze α-NAD+ as a substrate (Stevens et al., 2019 ▸; Wazir et al., 2020 ▸). In addition to hydrolyzing MAR from the target proteins, it has been reported that ADP-ribosylation of RNA and DNA can also be reversed by MacroD1, MacroD2, TARG1, poly-ADP-ribose-glycohydrolase (PARG) and ADP-ribosyl-acceptor-hydrolases (ARHs) (Sakthianandeswaren et al., 2018 ▸; Munnur et al., 2019 ▸; Munnur & Ahel, 2017 ▸).

Three-dimensional structures of ADPr-binding fragments of MacroD1 and MacroD2 have provided evidence that they are closely related at the sequence level (MacroD-type macrodomains), while TARG1 is unique among MAR hydrolases in employing a different catalytic mechanism; it is more closely related to ALC-type macrodomains (Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸; Chen et al., 2011 ▸; Rack et al., 2016 ▸). In human TARG1, hydrolysis progresses via a conserved lysine residue that makes a nucleophilic attack on the C1′′ atom of the distal ribose. This leads to the formation of a lysyl-ADPr intermediate and the release of an unmodified glutamate/aspartate residue. The covalent intermediate is later resolved via a proximal catalytic aspartate residue, releasing ADPr from TARG1 and making it readily available for the next hydrolysis reaction (Sharifi et al., 2013 ▸; Bütepage et al., 2018 ▸). In contrast, MacroD1 and MacroD2 reverse the glutamate/aspartate-linked mono-ADP-ribosylation (MARylation) through a nucleophilic attack by an active-site water molecule and without the formation of protein-linked reaction intermediates (Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸).

Previously, Jankevicius and coworkers solved the structure of MacroD2 in complex with ADPr. They analysed the structural rearrangements upon ligand binding by comparing the complex structure with an apo structure of MacroD1, because crystal structures of human MacroD2 without a ligand bound were not available (Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸). Here, we report apo crystal structures of human MacroD2 in three different crystal forms. Comparison of apo and ADPr-bound MacroD2 structures revealed that despite the fact that the ADPr-binding site is highly pre-formed, some conformational changes in the side chains of the active-site residues occur upon ligand binding. The reported crystal forms will allow ligand-soaking experiments that could facilitate chemical probe and drug-discovery efforts for MAR-hydrolyzing macrodomains.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein production

A human MacroD2 construct (residues 7–243) was cloned into pNH-TrxT vector containing an N-terminal polyhistidine and thioredoxin tag. The recombinant protein was expressed and purified as described previously (Haikarainen et al., 2018 ▸) and a brief summary is provided here. Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells were used for protein expression in Terrific Broth auto-induction medium. The cells were grown until the OD600 reached 1.0 and were then incubated at 18°C for 16 h for protein expression. The protein was purified using nickel-affinity chromatography and the N-terminal tags were removed with TEV protease. The final purification was achieved by size-exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg (GE Healthcare) gel-filtration column pre-equilibrated with gel-filtration buffer [20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 5%(v/v) glycerol, 1 mM TCEP]. The same buffer was also used as a storage buffer for the protein, which was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and placed at −70°C.

2.2. Crystallization

2.2.1. The starting point for crystallization

Screening of crystallization conditions was initiated with the PEG/Ion HT screen (Hampton Research). We used the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion technique at room temperature (RT). A 100 nl drop of 10 mg ml−1 MacroD2 solution was mixed with an equal volume of crystallization solution using a Mosquito pipetting robot (TTP Labtech) and equilibrated against 50 µl crystallization solution.

2.2.2. Optimization

Optimization of the crystallization condition was performed using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion technique supplemented with the streak-seeding method at RT. A 2 µl drop of 8–10 mg ml−1 MacroD2 solution was mixed with an equal volume of the crystallization solution. Homogeneous streak-seeding was performed after a 10 min pre-equilibration of the crystallization drops against 500 µl crystallization solution.

2.3. Data collection and processing

25%(v/v) glycerol was used as a cryoprotectant for the MacroD2 crystals. The crystals were soaked in the cryoprotectant for 2–3 min before flash-cooling with liquid nitrogen. We also supplemented the cryoprotectant with 1–3 mM Bay 11-7085, a small-molecule compound obtained as a screening hit from our recent study (Wazir et al., 2020 ▸). X-ray diffraction data were collected from the crystals on beamlines ID23-1 at ESRF, Grenoble, France and I04-1 at Diamond Light Source (DLS), Oxfordshire, UK. The data were processed and scaled with XDS (Kabsch, 2010 ▸). The data-collection statistics are presented in Table 1 ▸.

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics for the MacroD2 crystal structures.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| PDB code | 6y4y | 6y4z | 6y73 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| X-ray source | Beamline ID23-1, ESRF | Beamline I04-1, DLS | Beamline I04-1, DLS |

| Cryo-solution | 25%(v/v) glycerol | 25%(v/v) glycerol, 3 mM Bay 11-7085 | 25%(v/v) glycerol, 0.2 M ammonium tartrate dibasic pH 6.7, 1 mM Bay 11-7085 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9762 | 0.9762 | 0.91589 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Detector | PILATUS | PILATUS | PILATUS |

| Space group | P41212 | P43212 | P43 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 95.65, 95.65, 258.72 | 95.36, 95.36, 261.92 | 96.78, 96.78, 261.09 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–1.75 (1.80–1.75) | 50–1.90 (1.95–1.90) | 50–1.70 (1.74–1.70) |

| Total No. of reflections | 1472885 (104148) | 1280920 (79871) | 1823516 (136691) |

| No. of unique reflections | 121564 (8864) | 95967 (7009) | 261897 (19354) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 13.27 (1.70) | 18.92 (1.25) | 8.98 (1.41) |

| CC1/2 (%) | 99.8 (70.9) | 100 (74.6) | 99.5 (61.0) |

| R r.i.m. (%) | 11.2 (161.3) | 8.5 (172.9) | 13.3 (124.2) |

| Model bulding and refinement | |||

| R factor (%) | 20.36 | 20.00 | 18.21 |

| R free (%) | 22.76 | 22.80 | 20.31 |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 6881 | 6922 | 13902 |

| Ligands† | 16 | 10 | 88 |

| Water | 517 | 440 | 1603 |

| Total | 7414 | 7372 | 15593 |

| R.m.s.d. | |||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Angles (°) | 1.43 | 1.56 | 1.35 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | |||

| Overall | 37.50 | 43.79 | 32.06 |

| Protein | 36.25 | 45.75 | 26.87 |

| Ligands† | 40.11 | 42.53 | 37.11 |

| Water | 36.24 | 43.10 | 32.22 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||

| Favoured (%) | 98.44 | 98.00 | 98.64 |

| Allowed (%) | 1.56 | 2.00 | 1.36 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Tartrate and glycerol molecules.

2.4. Structure solution and refinement

The structures were solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 2010 ▸), in which the MacroD2 structure (PDB entry 4iqy; Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸) was used as a search model. Model building and refinement were performed with Coot and REFMAC5, respectively, in CCP4i2 (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸; Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸; Potterton et al., 2018 ▸). The structures were visualized with PyMOL version 1.7.2.1 (Schrödinger). The model-building and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1 ▸.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Crystallization and crystal structures of MacroD2 in three different space groups

MacroD2 was finally crystallized using a solution consisting of 0.2 M ammonium tartrate dibasic pH 6.7, 20%(w/v) PEG 3350 as a precipitant together with the homogeneous streak-seeding technique. Octahedron-shaped crystals were obtained in 24 h and the crystals diffracted to high resolution (1.70–1.90 Å; Fig. 1 ▸ a). Three crystal structures of MacroD2 were solved in space groups P41212 (PDB entry 6y4y), P43212 (PDB entry 6y4z) and P43 (PDB entry 6y73) (Table 1 ▸). The asymmetric units of the structures in space groups P41212 and P43212 contained four molecules, while the asymmetric unit of the structure in space group P43 contained eight molecules. All three structures contained tartrate ions in the interfaces of monomers, where the ions make hydrogen-bond interactions between the protein molecules. There are slight differences in the modelled residues between the crystal structures. The MacroD2 crystal structure in space group P41212 includes residues 9–241, while the structures in space groups P43212 and P43 include residues 7–241 and 8–241, respectively. Residues 48–66 are not visible in the electron-density map and therefore were not modelled in any of the structures. The N-terminal region (residues 7–47) contains loop and helical sections and the macrodomain region (residues 78–228) consists of an α–β–α sandwich with a central six-stranded β-sheet (Figs. 1 ▸ b, 1 ▸ c and 1 ▸ d).

Figure 1.

Results of MacroD2 crystallization and structure determination. (a) Three-dimensional crystals of MacroD2 in a hanging drop. (b, c, d) Ribbon representations of the secondary structures of apo MacroD2 in space groups (b) P41212 (PDB entry 6y4y, chain A; light blue), (c) P43212 (PDB entry 6y4z, chain A; warm pink) and (d) P43 (PDB entry 6y73, chain A; salmon). The N- and C-termini are labelled and the internally missing fragment is presented as a dashed line.

The root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) values for superimposition of the monomers of the asymmetric units are 0.35–0.55 Å for space group P41212 (214–216 Cα atoms), 0.30–0.48 Å for space group P43212 (213–214 Cα atoms) and 0.16–0.58 Å for space group P43 (213–216 Cα atoms), indicating that there are no significant structural differences between the protein molecules in the asymmetric units. Fig. 2 ▸ shows the superimposition of the three crystal forms, demonstrating that all of these individual models are entirely consistent with one another (with an r.m.s.d. of 0.25 Å for 179 Cα atoms). The only exception is the N-terminal elongated α-helix in chain A of the P43212 structure and an extended loop in chain D of the P43 structure. The refined structures exhibit good geometry, with >98% of residues in the favoured region of the Ramachandran plot and no outliers (Table 1 ▸).

Figure 2.

Ribbon representation of the superimposed crystal forms of MacroD2. Secondary structures of the P41212 (PDB entry 6y4y), P43212 (PDB entry 6y4z) and P43 (PDB entry 6y73) structures are coloured light blue, warm pink and salmon red, respectively. The N-terminal elongated α-helix in the P43212 structure and the extended loop in the P43 structures are marked as exceptions.

We used the same MacroD2 construct for both crystallization and inhibitor screening (Wazir et al., 2020 ▸). Immediately after screening, we tried to obtain a complex structure of MacroD2 with a hit compound, Bay 11-7085, by soaking the MacroD2 crystals with the compound. When we subsequently performed quality analysis for the compound by mass spectrometry we did not detect the intact compound, which was likely to be owing to degradation (Wazir et al., 2020 ▸). We also did not see any complete electron density for Bay 11-7085 in the crystal structures. Instead, we only observed smaller electron-density features in the active site of MacroD2, which may or may not be caused by unidentified degradation products of the compound. As we could not fully identify the origin of these electron-density features, we did not build anything into them (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). The presence of the Bay 11-7085 fragments in the P43212 and P43 structures does not induce any disorder or conformational changes in the crystal structures.

3.2. Comparison of the MacroD2 apo and ADPr-complex structures

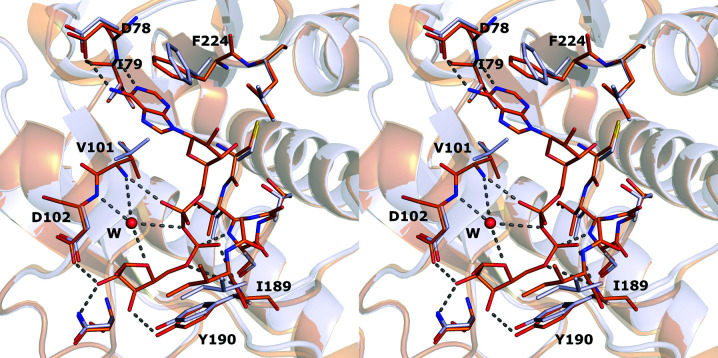

To obtain insight into the substrate binding and to reveal possible conformational changes, we compared our MacroD2 structures with the ADPr-bound MacroD2 complex structure (PDB entry 4iqy; Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸). Since the conformations of the active-site residues in all three of our structures were identical, we used the apo structure (PDB entry 6y4y) for this analysis. The superimposition (r.m.s.d. of 0.24 Å for 181 Cα atoms) shows that the apo structure closely matches the complex structure (Fig. 3 ▸). It also reveals that Val101, Ile189 and Phe224 adopt different conformations in the absence of the ligand. Another difference is the activated water molecule, which is only observed in the MacroD2–ADPr complex structure. As summarized previously by Jankevicius and coworkers, this activated H2O molecule makes a nucleophilic attack on the C1′′ atom of the distal ribose during hydrolysis (Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸). The water molecule is located in a cleft between loops 1 and 2 and also forms hydrogen-bond interactions between the ADPr distal ribose and α-phosphate. The arrangement of the active-site loops is essentially identical in both structures, indicating that the binding site is highly pre-formed and that the binding of ADPr does not cause major conformational changes in the protein binding site.

Figure 3.

Superimposition of MacroD2 crystal structures: the MacroD2–ADPr complex structure (PDB entry 4iqy; Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸; orange) and ligand-free MacroD2 (PDB entry 6y4y; light blue). ADPr and its surrounding residues are shown as sticks. The labelled residues are important for the catalytic activity of the enzyme. Hydrogen bonds are presented as dashed lines. W is the catalytic water molecule in the MacroD2–ADPr complex.

3.3. Comparison of MacroD1 and MacroD2 crystal structures

Structural analysis of MacroD2 in complex with ADPr (PDB entry 4iqy; Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸) revealed that it is extensively homologous to the previously reported MacroD1 structure (PDB entry 2x47; Chen et al., 2011 ▸). Both macrodomains have similar N-terminal regions arranged as an elongated chain comprising helical segments and a short β-strand, and a macrodomain region comprised of an α–β–α sandwich with a central six-stranded β-sheet (Chen et al., 2011 ▸; Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸). Because this structural information may also aid in the structure-based design of inhibitors of hydrolyzing macrodomains, we analysed the structures of ligand-free MacroD1 and MacroD2 (PDB entry 6y4y; Fig. 4 ▸ a).

Figure 4.

Crystal structure comparison of MacroD2 (PDB entry 6y4y) and MacroD1 (PDB entry 2x47; Chen et al., 2011 ▸) catalytic fragments showing their mono-ADP-ribosyl-hydrolase functions. The MacroD2 structure is in light blue and ligand-free MacroD1 is in cyan. The ADPr in the MacroD2–ADPr structure is coloured orange (PDB entry 4iqy; Jankevicius et al., 2013 ▸). (a) Overall view of the superimposition of apo MacroD2 and MacroD1. Unstructured loops are denoted by dashed lines. (b) The conformational difference of loop 2 between MacroD1 and MacroD2 is indicated by a black arrow. ADPr and its surrounding residues are shown as sticks. The labelled residues are important for the catalytic activities of these enzymes. Hydrogen bonds are presented as dashed lines.

As stated previously, there are no major differences in the ADPr-binding site of MacroD2 with and without ligand, and it is highly pre-formed. However, this is not the case in MacroD1 as loop 2 near the active site is in an open conformation in apo MacroD1. Despite the fact that the structure of the MacroD1–ADPr complex is not available, it is likely that Phe272 in MacroD1, which corresponds to Tyr190 in MacroD2, moves by almost 13 Å upon ligand binding to tightly coordinate the distal ribose of ADPr (Fig. 4 ▸ b). The orientation of Phe224 in MacroD1 has to also change to provide π-stacking interactions with the adenosine moiety of ADPr. These conformational changes upon substrate binding, together with the water molecule coordinated between the ADPr and the protein, are the key features of the ligand-binding site and are important for the MAR-hydrolyzing function of these enzymes.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we have found a new crystallization condition for MacroD2 that shows a pre-formed active site, where only small conformational changes occur in the residues upon ADPr binding. This apo form of MacroD2 found in all of the three different crystal forms can be utilized effectively for binding studies, as major conformational changes in the crystal are not required to accommodate the ligand. Co-crystal structures with ligands could further assist in exploring the cellular roles of the ADP-ribosyl-hydrolyzing macrodomains.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: MacroD2, P41212, 6y4y

PDB reference: P43212, 6y4z

PDB reference: P43, 6y73

Supplementary Figures. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X20011309/ow5023sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members at both the ESRF and DLS synchrotron-radiation facilities. We also thank Dr Teemu Haikarainen for help in cloning and purification of the MacroD2 expression construct. The use of the facilities and expertise of the Biocenter Oulu Structural Biology core facility, a member of Biocenter Finland, Instruct-ERIC Centre Finland and FINStruct, is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Sigrid Juséliuksen Säätiö grant . Academy of Finland, Terveyden Tutkimuksen Toimikunta grants 287063 and 294085.

References

- Bütepage, M., Preisinger, C., von Kriegsheim, A., Scheufen, A., Lausberg, E., Li, J., Kappes, F., Feederle, R., Ernst, S., Eckei, L., Krieg, S., Müller-Newen, G., Rossetti, G., Feijs, K. L. H., Verheugd, P. & Lüscher, B. (2018). Sci. Rep. 8, 6748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen, D., Vollmar, M., Rossi, M. N., Phillips, C., Kraehenbuehl, R., Slade, D., Mehrotra, P. V., von Delft, F., Crosthwaite, S. K., Gileadi, O., Denu, J. M. & Ahel, I. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 13261–13271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haikarainen, T., Maksimainen, M. M., Obaji, E. & Lehtiö, L. (2018). SLAS Discov. 23, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jankevicius, G., Hassler, M., Golia, B., Rybin, V., Zacharias, M., Timinszky, G. & Ladurner, A. G. (2013). Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 508–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Munnur, D. & Ahel, I. (2017). FEBS J. 284, 4002–4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Munnur, D., Bartlett, E., Mikolčević, P., Kirby, I. T., Rack, J. G. M., Mikoč, A., Cohen, M. S. & Ahel, I. (2019). Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 5658–5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Potterton, L., Agirre, J., Ballard, C., Cowtan, K., Dodson, E., Evans, P. R., Jenkins, H. T., Keegan, R., Krissinel, E., Stevenson, K., Lebedev, A., McNicholas, S. J., Nicholls, R. A., Noble, M., Pannu, N. S., Roth, C., Sheldrick, G., Skubak, P., Turkenburg, J., Uski, V., von Delft, F., Waterman, D., Wilson, K., Winn, M. & Wojdyr, M. (2018). Acta Cryst. D74, 68–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rack, J. G. M., Perina, D. & Ahel, I. (2016). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 85, 431–454. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, F., Feijs, K. L. H., Frugier, E., Bonalli, M., Forst, A. H., Imhof, R., Winkler, H. C., Fischer, D., Caflisch, A., Hassa, P. O., Lüscher, B. & Hottiger, M. O. (2013). Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 502–507. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sakthianandeswaren, A., Parsons, M. J., Mouradov, D. & Sieber, O. M. (2018). Oncotarget, 9, 33056–33058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, R., Morra, R., Appel, C. D., Tallis, M., Chioza, B., Jankevicius, G., Simpson, M. A., Matic, I., Ozkan, E., Golia, B., Schellenberg, M. J., Weston, R., Williams, J. G., Rossi, M. N., Galehdari, H., Krahn, J., Wan, A., Trembath, R. C., Crosby, A. H., Ahel, D., Hay, R., Ladurner, A. G., Timinszky, G., Williams, R. S. & Ahel, I. (2013). EMBO J. 32, 1225–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stevens, L. A., Kato, J., Kasamatsu, A., Oda, H., Lee, D.-Y. & Moss, J. (2019). ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 2576–2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wazir, S., Maksimainen, M. M., Alanen, H. I., Galera-Prat, A. & Lehtiö, L. (2020). SLAS Discov., https://doi.org/10.1177/2472555220928911.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: MacroD2, P41212, 6y4y

PDB reference: P43212, 6y4z

PDB reference: P43, 6y73

Supplementary Figures. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X20011309/ow5023sup1.pdf