Abstract

Objectives

Traditional Doppler measures have been used to predict cognitive performance in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. Novel measures, such as carotid plaque strain indices (CPSI), have shown associations with cognitive performance. We hypothesized that lower mean middle cerebral artery (MCA) velocities, higher bulb-internal carotid artery (ICA) velocities, MCA pulsatility index (PI) and CPSIs would be associated with poorer cognitive performance in individuals with advanced atherosclerosis.

Methods

Neurocognitive testing, carotid ultrasound, transcranial Doppler and carotid strain imaging were performed on 40 patients scheduled for carotid endarterectomy. Kendall tau correlations were used to examine relationships between cognitive tests and surgical side maximum peak systolic velocity (PSV) (from bulb, proximal, mid or distal ICA), mean MCA velocity and PI and maximum CPSI (axial, lateral and shear strain indices used to characterize plaque deformations with arterial pulsation). Cognitive measures included age adjusted indices of verbal fluency, verbal and visual learning/memory, psychomotor speed, auditory attention/working memory, visuospatial construction, and mental flexibility.

Results

Participants were median age 71.0 (interquartile range [IQR] 9.75) years, 26 male (65%) and 14 female (35%). Traditional Doppler parameters, PSV, mean MCA velocity and MCA PI did not predict cognitive performance (p values all >0.05). Maximum CPSIs were significantly associated with cognitive performance (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Traditional velocity measurements of maximum bulb-ICA PSV, mean MCA velocity and PI were not associated with cognitive performance in patients with advanced atherosclerotic disease; however, maximum CPSIs were associated with cognitive performance. These findings suggest cognition may be associated with unstable plaque rather than blood flow.

Keywords: Carotid artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, vascular imaging/diagnostics

Introduction

Traditional Doppler measures such as mean blood flow velocity of the middle cerebral artery (MCA), pulsatility index (PI) of the cerebral arteries, peak systolic velocity (PSV) of the internal carotid artery (ICA), and cerebrovascular reactivity have been associated with cognitive performance and dementia.1–11 The mean velocity of blood flow in the MCA has been shown to be lower in individuals with Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia when compared with age matched controls.8, 9 The PI of the middle MCA has also been shown to be elevated in patients with Alzheimer dementia and vascular dementia compared to age matched controls, 6, 8, 9 and cerebral vascular pathology has been seen in patients with Alzheimer disease.12 Thus, it is hypothesized that increased vascular resistance downstream to the MCA is associated with decreased flow (manifested as lower mean velocity in the MCA) and increased vascular resistance (depicted as an increased PI).6, 8, 9 While this phenomenon of hemodynamic changes (lower mean flow velocity and increased resistance measured with the PI) have been explored in patients with disease and compared to healthy controls, these parameters have not been well described in individuals with advanced carotid atherosclerosis to characterize changes in cognition. Thus, we sought to explore the relationships of the surgical side Doppler velocities in the most stenotic segment of the vessel (carotid bulb to ICA [proximal, mid and distal] and flow in the ipsilateral MCA). We hypothesized that if traditional Doppler parameters were associated with cognition, these hemodynamic measures may be an additional tool for assessing symptomology in individuals with asymptomatic carotid stenosis. We hypothesized that lower mean MCA velocities, higher bulb-ICA velocities and higher MCA PI would be associated with poorer cognitive performance in individuals with advanced atherosclerosis (> 60% stenosis and scheduled for clinically indicated carotid endarterectomy based on asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis (ACAS)13 and the North American Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET)14 criteria). We also hypothesized that traditional Doppler measurements would perform similar to novel approaches of evaluating carotid plaque strain indices (CPSIs), where we have previously demonstrated that higher strain indices are associated with poorer cognitive performance.15–18

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were individuals enrolled in the Structural Stability of Carotid Plaque and Symptomatology study (R01 NS064034, PI: R. Dempsey, funded by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). From 2010–2018, 40 participants underwent neurocognitive testing, transcranial Doppler examination (for hemodynamic assessment and to monitor for high intensity transient signals [HITS]), a clinical carotid Doppler examination and carotid strain imaging performed on their surgical side. All 40 participants were scheduled for clinically indicated carotid endarterectomy based on ACAS and NASCET criteria. This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Boards. All patients provided informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Neurocognitive Testing

Each participant was administered the National Institute of Neurological Disorders (NINDS) and Canadian Stroke Network (CSN) 60-minute test battery. The NINDS-CSN battery is specifically designed for stroke patients to assess their executive function/attention, speeded psychomotor, verbal and nonverbal memory, language, and visuospatial skills. The entire test battery with accompanying citations is shown in Table 1 and these tests have been previously described.19 Incorporated in the statistical analyses were the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 4th edition (WAIS-IV) Information subtest for verbal semantic information, the Controlled Oral Word Association Test for verbal fluency,20,21 the, WAIS-IV Digit Symbol Test22 for psychomotor speed, Trail Making Test B,23 for speeded mental flexibility, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT)24 total learning test for verbal learning and delayed verbal memory,24 the WAIS-IV Block Design Test22 for visuospatial construction, the WAIS-IV Digit Span Test for auditory attention/working memory, and the Rey Complex Figure Delayed Recall Test25 for delayed visual memory.The Wechsler Adult Intelligence scale 4th edition (WAIS-IV) Digit Symbol Coding Test and Block Design Test are reported as scaled scores (mean=10, sd=3), T-scores (mean = 50, sd = 10) are reported for all other cognitive tests.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological Tests by Domain

| Domain | Ability | Test |

|---|---|---|

| Executive/Activation | Semantic Fluency | Animal Naming45,46 |

| Phonemic Fluency | Controlled Oral Word Association Test20, 21 | |

| Association/Speeded Psychomotor | Motor Sequencing | Trail Making Test (TMT A/B)23 |

| Psychomotor Speed | Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 4th edition (WAIS-IV) Digit Symbol Coding22 | |

| Language | Object Naming | Boston Naming Test (2nd Ed—short form)47,48 |

| General Knowledge | WAIS-IV Information22 | |

| Visuospatial | Figure Reproduction | Rey Complex Figure (Copy)25 |

| Visuospatial Construction | WAIS-IV: Block Design22 | |

| Learning and Memory | Verbal | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised: Total Learning24 |

| Visual | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised: Delayed free recall)24 | |

| Rey Complex Figure-Delayed Recall 25 | ||

Neuropsychological tests performed for this study to examine cognitive performance.

Transcranial Doppler

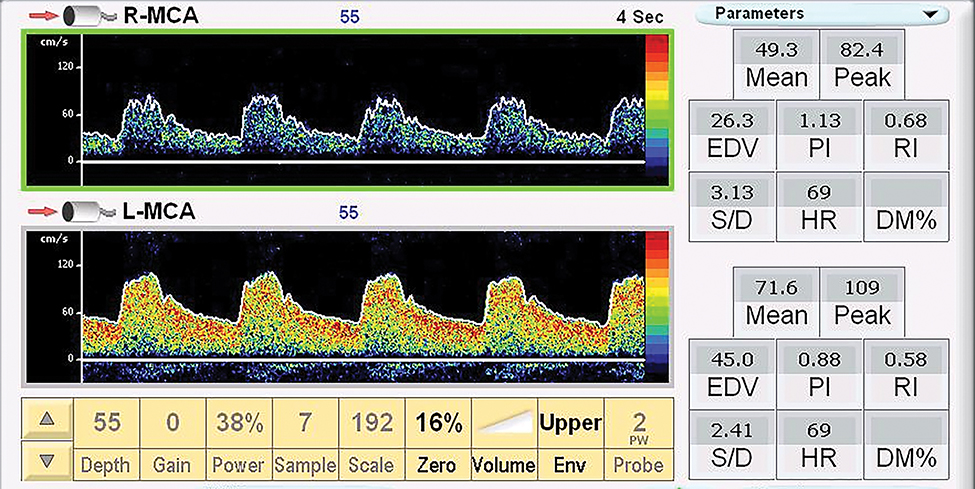

Patients were placed in the supine position with a transducer fixation device (helmet) placed on the head. Two, 2.0 MHz transducers were attached to the fixation device and placed over the trans-temporal window. The right and left MCA Doppler signals were identified and sampled at a depth between 45 and 60 mm. The PSV, mean velocity, end diastolic velocity, PI, resistive index (RI) and systolic to diastolic ratio in the MCA were acquired. The mean blood flow is the time average velocity of the envelope (maximal velocity) over one cardiac cycle.26 PI and RI were calculated from the Doppler signal. PI (unitless, Gosling PI) was calculated as follows: PI = (PSV – End diastolic velocity[EDV])/mean velocity) mean blood flow is the time average velocity of the envelope (maximal velocity) over one cardiac cycle.26 Resistance index (Pourcelot Resistance Index) was calculated: RI = (PSV – EDV) / PSV.26 Systolic to Diastolic ratio was calculated as the PSV / minimal diastolic velocity. These measures were calculated with the auto Doppler function on the transcranial Doppler system utilizing the peak envelope. All transcranial Doppler examinations were performed with a SONARA Digital Bilateral Systems transcranial Doppler system (Natus Neurology, Inc, Middleton, WI, USA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trancranial Doppler Signal form the Middle Cerebral Arteries.

Doppler sample in the right and left middle cerebral arteries (R-MCA, LMCA). * Mean = mean velocity cm/s, Peak = peak systolic velocity cm/s, EDV = end diastolic velocity cm/s, PI = pulsatility index, RI = resistive index, S/D = systolic/diastolic ratio, HR = heart rate.

Carotid Ultrasound

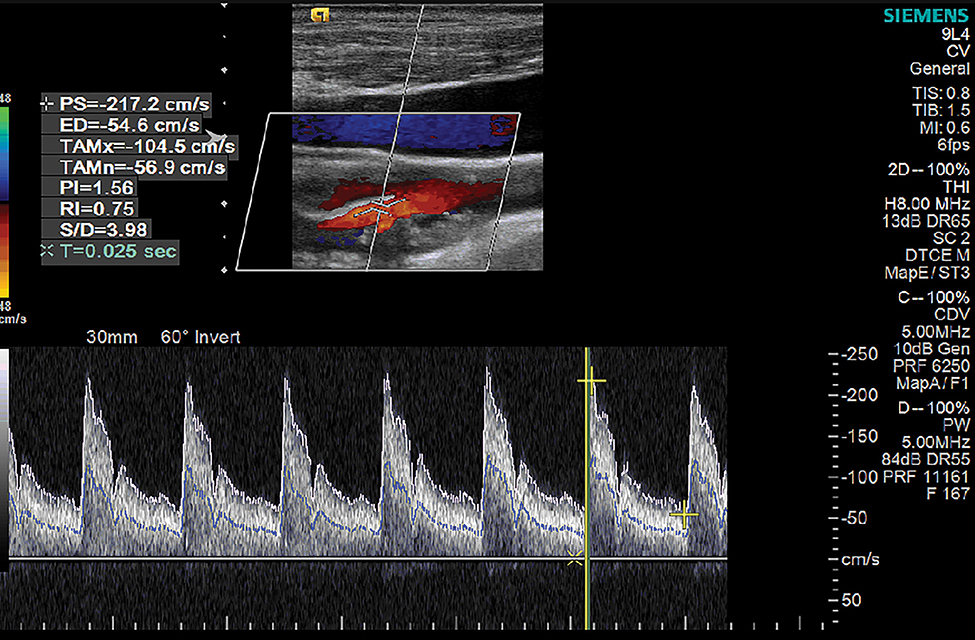

B-mode, pulsed wave Doppler, and color flow Doppler images of the bilateral common carotid, internal, and external carotid arteries were acquired with a 9L4 linear array transducer and an Acuson S2000 ultrasound system (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc, Malvern, PA, USA). Pulsed-wave Doppler was utilized to measure blood flow velocities. The Doppler sample volume was placed in the center of the vessel, and all samples were acquired at an angle of 60 degrees or less. Peak systolic and end diastolic velocities were recorded in the proximal, mid and distal segments of the common and internal carotid arteries, carotid bulb and external carotid arteries. Pulsatility index (PI), RI and systolic to diastolic ratio measurements were measured at each previously mentioned vessel segment (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Internal Carotid Artery Doppler.

Doppler sample in the internal carotid artery. Peak systolic (PS) velocity −217.2 cm/s, end diastolic velocity (ED) 54.6 cm/s. Temporal average max (TAMx) = −104.5 cm/s, temporal average mean (TAMn) = −56.9 cm/s, pulsatility index = 1.56, resistive index = 0.75, systolic/diastolic (S/D) ratio = 3.98, acceleration time (T) = 0.025 seconds.

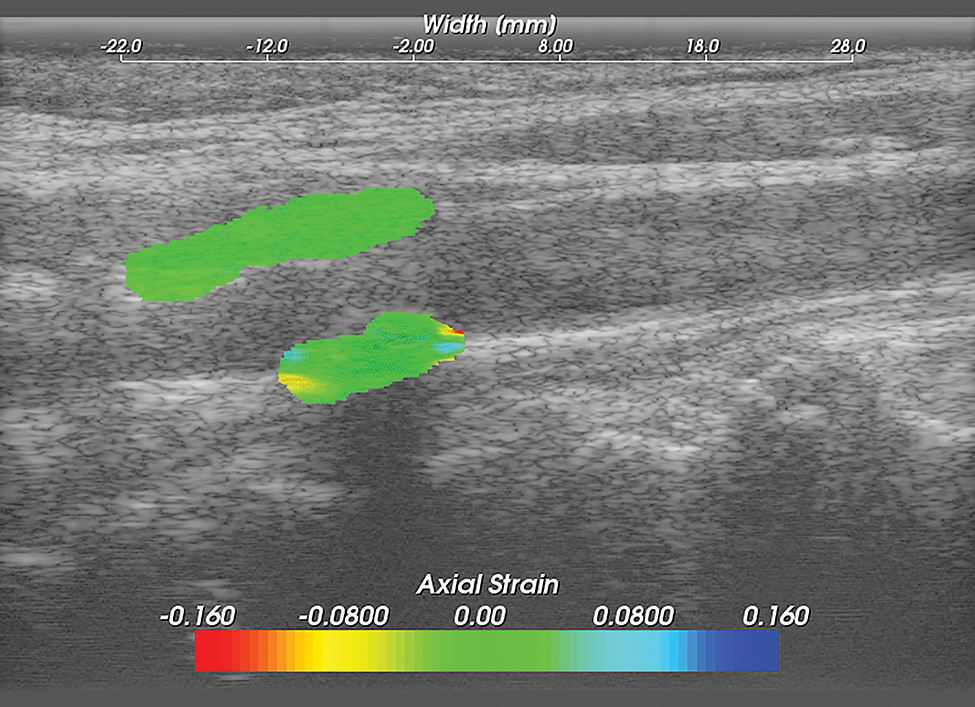

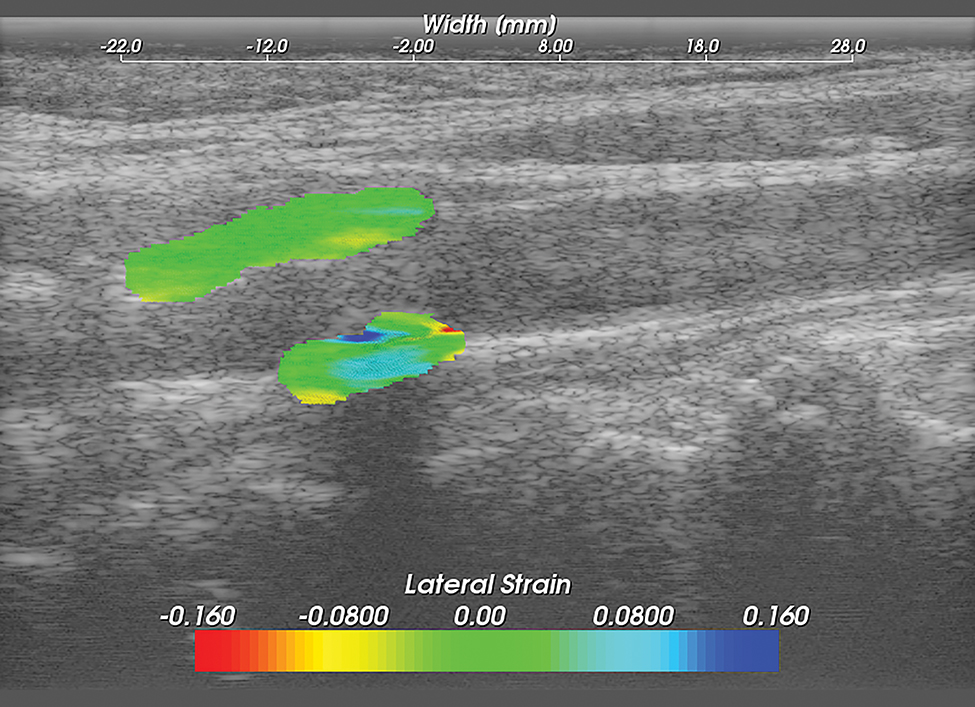

Carotid Strain Imaging

Methods for performing carotid strain imaging have been previously described.15–18, 27, 28 Briefly, Ultrasound radio frequency (RF) echo signal data loops were acquired with an 18L6 linear array transducer and Acuson S2000 ultrasound system (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc, Malvern, PA, USA). RF sampling frequency was 40 MHz. Plaque and adventitia were segmented utilizing the Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit (MITK). Displacement tracking of segmented regions from the end diastolic frame was automatically tracked over two complete cardiac cycles (25 frames/cycle) using a hierarchical block-matching motion tracking algorithm previously developed in our laboratory,27 and currently implemented on a GPU.29 Corresponding strain tensors are computed from the gradient of the respective displacement vectors. Axial, lateral and shear strains are defined as , and , respectively where dy and dx denote axial and lateral displacement vectors. Accumulated axial and lateral displacements vectors defined as: and where and are the incremental axial and lateral displacements estimated at the ith frame, the accumulated displacements and are the accumulated axial and lateral displacements integrated from the 2nd frame to the Nth frame. Accumulated strains can then be calculated as: where , and represents accumulated axial, lateral and shear strains over a cardiac cycle respectively (Figures 3,4,5).

Figure 3. Carotid Axial Strain Image.

Carotid strain image. Axial strain in the segmented region overlaid on the corresponding B-mode.

Figure 4. Carotid Lateral Strain Image.

Carotid strain image. Lateral strain in the segmented region overlaid on the corresponding B-mode.

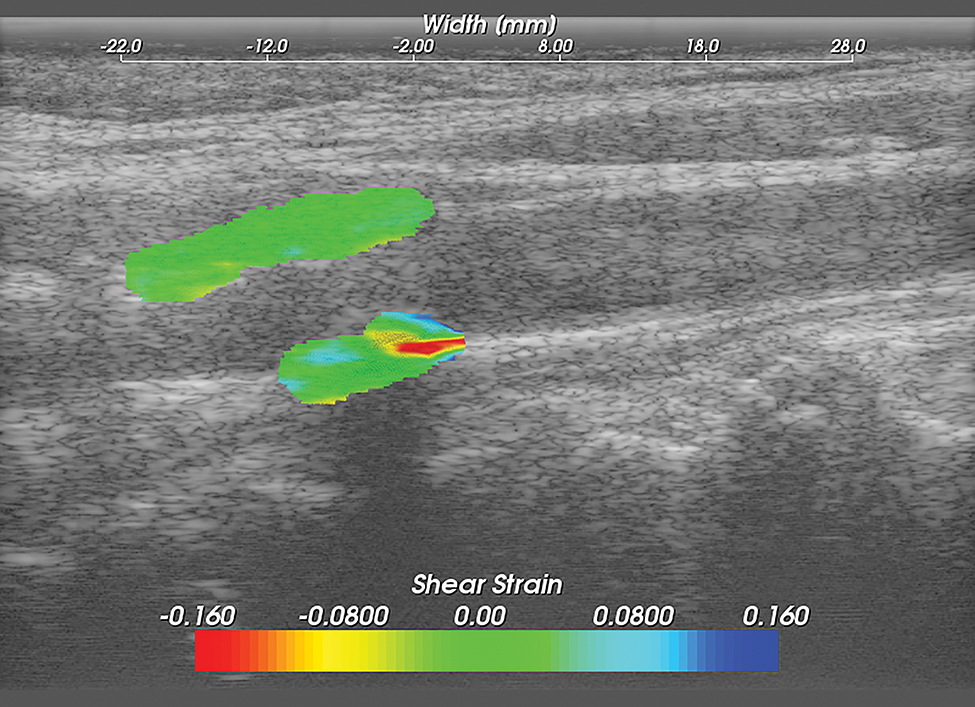

Figure 5. Carotid Shear Strain Image.

Carotid strain image. Shear strain in the segmented region overlaid on the corresponding B-mode.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Kendall tau correlations were used to examine relationships between the cognitive measures and the maximum PSV (PSV; from bulb, proximal, mid or distal ICA), mean MCA velocity and PI (on surgical side) and CPSIs (maximum axial, lateral and shear strain indices used to characterize plaque deformations with arterial pulsation). To determine if contralateral hemodynamics may influence associations with cognitive performance we also computed the average (average of surgical and contralateral non-surgical side) maximum PSV (PSV; from bulb, proximal, mid or distal ICA), average mean MCA velocity and average PI. Kendall tau correlations were also used to examine relationships between the average (average of surgical and contralateral non-surgical side) maximum PSV (PSV; from bulb, proximal, mid or distal ICA), mean MCA velocity and PI. Cognitive measures included age-adjusted indices of verbal fluency, verbal and visual learning/memory, psychomotor speed, auditory attention/working memory, visuospatial construction, and mental flexibility.

Results

Participants

Forty participants enrolled in the Structural Stability of carotid Plaque and Symptomatology study (R01 NS064034, PI: R. Dempsey funded by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) scheduled for clinically indicated carotid endarterectomy underwent neurocognitive testing, comprehensive clinical carotid ultrasound imaging, carotid strain imaging and ipsilateral transcranial Doppler examination in which hemodynamic velocity data was acquired. Participants were median age 71.0 ( IQR 9.75) years, 26 male (65%) and 14 female (35%). Twenty (50%) were symptomatic. Participants also had clinical imaging performed (computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) to determine the percent stenosis prior to surgery. The median stenosis was 70.0 (IQR 10.0) percent. Median score [IQR] performance for each cognitive test (Controlled Oral Word Association Test, 41.00 [10.00]; Trail Making Test B, 44.00 [15.00]; WAISIV Digit Symbol Coding, 9.00 [2.50]; Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised Total Learning, 45.00 [18.25]; Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised Delayed Recall, 44.00 [18.00]; WAIS-IV Block Design, 10.00 [2.5]; and Rey Complex Figure Delayed Recall, 46.00[16.50]), Doppler values (PSV, 194.4 [131.60]; MCA mean velocity, 42.90 [21.50]; and MCA PI, 1.05 [0.36]), and strain values (axial, 17.97 [22.24]; lateral, 12.15 [11.25]; and shear, 20.72 [22.89]) are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Variable |

Median

(IQR) N (%) |

||

| Age (years) | 71 (9.75) | ||

| Female | 14 (35%) | ||

| Percent Stenosis | 70 (10%) | ||

| Symptomatic Patients | 20 (50%) | ||

|

Neurocognitive Tests | |||

| Test | Ability | Median | IQR |

| Controlled Oral Word Association Test | Verbal (phonemic) fluency | 41.00 | 10.00 |

| Trail Making Test -B | Motor sequencing (speeded metal flexibility) | 44.00 | 15.00 |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 4th edition (WAIS-IV) Digit Symbol Coding | Psychomotor speed | 9.00 | 2.50 |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning –

Revised Total Learning |

Verbal learning | 45.00 | 18.25 |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning –

Revised Delayed Recall |

Delayed verbal memory | 44.00 | 18.00 |

| WAIS-IV: Block Design | Visuospatial construction | 10.00 | 2.50 |

| Rey Complex Figure Delayed Recall | Figure reproduction (delayed visual memory) | 46.00 | 16.50 |

| Doppler Velocity and Pulsatility Index | |||

| Variable | Median | Interquartile Range | |

| Surgical side PSV (Highest PSV Bulb, ICA) cm/s | 194.40 | 131.60 | |

| Surgical side MCA mean velocity cm/s | 42.90 | 21.50 | |

| Surgical side MCA PI unitless | 1.05 | 0.36 | |

| Strain | |||

| Variable | Median | Interquartile Range) | |

| Maximum axial % | 17.97 | 22.24 | |

| Maximum lateral % | 12.15 | 11.25 | |

| Maximum shear % | 20.72 | 22.89 | |

ICA=internal carotid artery, MCA=middle cerebral artery, PI=pulsatility index, PSV=peak systolic velocity.

Traditional Doppler Parameters

Traditional Doppler parameters of the highest PSV in the carotid bulb to distal ICA segment, mean velocity in the MCA, and PI in the MCA were not significantly related to cognitive performance in any of the tests (all P > .05). For the surgical side, Kendall tau correlations (r) ranged from −0.02 to −0.14 for the PSV in the bulb–distal ICA segment, −0.01 to 0.20 for the mean MCA velocity, and − 0.02 to 0.12 for the MCA PI (Table 3). The average PSV (bulb to ICA), mean blood flow velocity of the MCA, and mean PI were also not significantly associated with cognitive performance (data not shown; all P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Correlations Cognitive Tests, Traditional Doppler Measures and Strain Indices.

| Cognitive Test | n=Traditional Doppler and Cognition |

Surgical

Side Maximum PSV Kendall Tau Correlation |

Surgical Side MCA Mean Velocity Kendall Tau Correlation |

Surgical Side MCA PI Kendall Tau Correlation |

|||

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | ||

| Verbal fluency (phonemic)* | 40 | −0.09 | 0.433 | −0.12 | 0.303 | 0.08 | 0.475 |

| Psychomotor speed | 40 | −0.09 | 0.444 | 0.03 | 0.814 | −0.08 | 0.509 |

| Speeded mental flexibility* | 39 | −0.05 | 0.654 | 0.09 | 0.403 | −0.02 | 0.875 |

| Verbal learning* | 40 | −0.10 | 0.369 | 0.05 | 0.683 | 0.12 | 0.293 |

| Delayed verbal memory* | 40 | −0.11 | 0.315 | 0.20 | 0.072 | 0.02 | 0.842 |

| Visuospatial construction* | 39 | −0.13 | 0.276 | −0.01 | 0.922 | −0.12 | 0.298 |

| Auditory attention/working memory* | 40 | −0.14 | 0.239 | −0.20 | 0.083 | 0.03 | 0.786 |

| Delayed visual memory* | 39 | −0.02 | 0.828 | 0.09 | 0.417 | −0.10 | 0.396 |

| Maximum Axial Stain | Maximum Lateral Strain | Maximum Shear Strain | |||||

| Cognitive Test | n=Strain and Cognition | Kendall Tau Correlation | Kendall Tau Correlation | Kendall Tau Correlation | |||

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | ||

| Verbal fluency (phonemic)* | 40 | −0.20 | 0.081 | −0.22 | 0.046 | −0.14 | 0.202 |

| Psychomotor speed | 40 | −0.40 | <0.001 | −0.25 | 0.031 | −0.35 | 0.003 |

| Speeded mental flexibility* | 39 | −0.35 | 0.002 | −0.29 | 0.010 | −0.35 | 0.002 |

| Verbal learning* | 40 | −0.18 | 0.115 | −0.08 | 0.476 | −0.05 | 0.649 |

| Delayed verbal memory* | 40 | −0.16 | 0.161 | −0.01 | 0.963 | −0.03 | 0.779 |

| Visuospatial construction* | 39 | −0.13 | 0.276 | −0.04 | 0.760 | −0.10 | 0.385 |

| Auditory attention/working memory* | 40 | −0.24 | 0.036 | −0.10 | 0.396 | −0.01 | 0.906 |

| Delayed visual memory* | 39 | −0.20 | 0.077 | −0.12 | 0.276 | −0.22 | 0.050 |

Verbal fluency (phonemic): Controlled Oral Word Association Test; psychomotor speed: Digit Symbol subtest from the WAIS-IV; speeded mental flexibility: Trail Making Test B; verbal learning: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised Total Learning; delayed verbal memory: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised Delayed Recall; visuospatial construction: Block Design Subtest from the WAIS IV; auditory attention/working memory: Digit Span subtest from the WAIS-IV; delayed visual memory: Rey Complex Figure Delayed Recall. Modified with permission from Mitchell C, Wilbrand SM, Cook TD, Meshram NH, Steffel CN, Nye R, Varghese T, Hermann BP and Dempsey RJ. Traditional Doppler Measures Do Not predict Cognition in a Cohort With Advanced Atherosclerosis. Stroke. 50:Suppl_1 abstract WMP47.49

MCA=middle cerebral artery, PI=pulsatility index, PSV=peak systolic velocity.

Carotid Strain Imaging

Maximum strain values were significantly associated with cognitive performance (P < .05; Table 3). Maximum axial strain CPSIs were significantly inversely correlated with WAIS-IV Digit Symbol test performance (r = −0.40; P <0.001), Trail Making Test B (r = −0.35; P = 0.002); and WAIS-IV Digit Span (r = −0.24; P = .036). Maximum lateral strain CPSIs were significantly inversely correlated with the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (r = −0.22; P = .046), WAIS-IV Digit Symbol (r = −0.25; P = .031), and Trail Making Test B (r = −0.29; P = .010), and maximum shear strain CPSIs were significantly correlated with WAIS-IV Digit Symbol (r = −0.35; P = .003), Trail Making Test B (r = −0.35; P = .002), and Rey Complex Figure Delayed Recall (r = −0.22; P = .050) (Table 3).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that traditional Doppler measures such as highest PSV in the bulb to ICA, mean flow velocity of the MCA and PI of the MCA are not indicative of cognitive performance in individuals with advanced atherosclerosis. Axial, lateral and shear strain indices were significantly related to cognitive performance. We have previously hypothesized that CPSIs represent a novel measure for assessing the pulsatility of plaque and that plaques with higher strain are more susceptible to the release of microemboli which may be resulting in brain damage contributing to cognitive decline.15–18, 28, 30, 31

The significance of these results is that measurement of CPSIs in plaques may represent a novel method for following patients and assisting with management in patients with advanced atheroscleriosis.15–18, 28, 30–32 The findings of this study suggest that traditional measures may not be the best way to follow patients with asymptomatic carotid arterial stenosis. While velocity information has been used historically to estimate the percent stenosis,33–35 stenosis alone may not be indicative of brain damage occurring due to the release of microemboli from unstable carotid plaque and thus asymptomatic patients may not be fully asymptomatic in that they may have cognitive symptoms of decline that are not associated with the current clinical examination.

Others have demonstrated that cerebral blood flow diminishes with age and is reduced in patients with Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, vascular cognitive impairment and cognitive decline in non-demented individuals.3, 6, 8, 9, 36–39 However, in many of these studies comparisons were made between healthy controls and patients with disease.3, 6, 39

Our study focused on evaluation of individuals with advanced atherosclerosis to see if Doppler hemodynamics were associated with cognitive function in individuals with advanced disease. Our findings suggest that Doppler measures may not be the best way to identify patients at highest risk for cognitive decline in individuals with advanced carotid atherosclerosis. Others have suggested that hypo perfusion, secondary to high-grade carotid stenosis contributes to cognitive impairment through chronic ischemia.40–42 Since the ICA contributes flow to the MCA, it is proposed that the MCA mean blood flow velocity can be used as an indirect measure for cerebral perfusion and thus, lower MCA mean velocities would be indicative of decreased perfusion.1,6 Increased PIs are thought to represent increased vascular resistance due to damage to small vessels and capillaries.39 Increased MCA PIs have also been associated with increased white matter hyper intensity lesion burden with MRI brain imaging.39 The reason our findings may differ from others is that our study population consisted of individuals with advanced atherosclerosis and not specifically looking for difference between healthy controls or individuals with vascular cognitive impairment– non dementia and individuals without vascular cognitive impairment.

Our findings also demonstrated that strain measures were associated with cognitive performance. We have previously demonstrated associations of carotid strain imaging with cognitive performance and associations with total white matter hyper intensity lesion volume.15–18, 28, 43 We hypothesize that vascular strain indices are a measure of plaque instability with higher strains associated with plaques that are more likely to release microemboli resulting in brain damage contributing to cognitive decline. Previously we have demonstrated that patients with advanced carotid atherosclerosis had poorer cognitive performance compared to age matched controls demonstrated loss from their premorbid IQ regardless of if they presented with neurologic symptoms (stroke, transient ischemic attack, speech, motor or visual deficits).19 We have also demonstrated that patients with advanced atherosclerosis have similar plaque histopathology findings at the time of carotid endarterectomy suggesting that both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients have plaque features that are similar and capable of releasing microemboli.44 Thus, it becomes imperative to identify new measures, such as CPSIs, to further characterize plaque instability and optimize treatment of carotid atherosclerosis to halt and/or delay the onset of cognitive decline associated with vascular disease.

Limitations

This is a small study (n=40) and did not image control participants. Also, all participants had advanced carotid atherosclerosis and were scheduled for clinically indicated carotid endarterectomy. These individuals may already have altered cerebral hemodynamics based on their advanced disease state. Therefore, it is not known how traditional Doppler measurements for individuals with advanced carotid atherosclerosis in our study would differ with healthy age matched controls. However, the aim of this study was to see if these measures were associated with cognitive performance and if they could they be used to assist with treatment planning to halt or delay vascular cognitive decline. Future work will require larger prospective longitudinal studies with aims developed to evaluate the best noninvasive measurement techniques for following patients and maximizing treatment to halt or delay cognitive decline associated with carotid vascular disease.

In conclusion, traditional velocity measurements of maximum bulb-ICA PSV, mean MCA velocity and PI were not associated with cognitive performance in patients with advanced atherosclerotic disease; however, maximum CPSIs were associated with cognitive performance. Findings suggest that cognition may be associated with unstable plaque (plaques at greater risk for rupture) rather than blood flow in individuals with advanced atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01 NS064034, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F31 HL 141008 and by the National Institutes of Health, under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 HL-007936, from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Cardiovascular Research Center. We gratefully acknowledge the support of NVIDIA Corporation with the donation of the Tesla K40 GPU used for carotid strain imaging. Support for carotid strain imaging research was also provided by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin–Madison with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation. We are grateful to Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., for providing the S2000 Axius Direct Ultrasound Research Interface (URI) and software licenses. The authors would like to thank Megan Evans for her assistance with manuscript preparation and would like to thank all of the participants in this study.

DisclosuresDrs Varghese, Hermann, and Dempsey have a patent (Varghese T, Dempsey RJ, Hermann BP. Characterization of vulnerable plaque using dynamic analysis. US2009/0198129 A1). Dr Mitchell reports other activities with Davies Publishing, Inc, textbook author, Elsevier, Wolters-Kluwer, author textbook chapters, and W. L. Gore & Associates contracted research grants to University of Wisconsin-Madison, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no disclosures.

References

- 1.Biedert S, Förstl H and Hewer W. The value of transcranial Doppler sonography in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer disease vs multi-infarct dementia. Mol Chem Neuropathol 1993; 19:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caplan GA, Lan Z, Newton L, Kvelde T, McVeigh C, Hill MA. Transcranial Doppler to measure cerebral blood flow in delirium superimposed on Dementia. A cohort study. JAMDA 2014; 15:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claassen JA, Diaz-Arrastia R, Martin-Cook K, Levine BD, Zhang R. Altered cerebral hemodynamics in early Alzheimer disease: a pilot study using transcranial Doppler. J Alzheimers Dis 2009; 17:621–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demarin V and Morovic S. Ultrasound subclinical markers in assessing vascular changes in cognitive decline and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2014; 42 Suppl 3 S259–S266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demarin V, Zavoreo I, Kes VB. Carotid artery disease and cognitive impairment. J Neurol Sci 2012; 322:107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doepp F, Valdueza JM and Schreiber SJ. Transcranial and extracranial ultrasound assessment of cerebral hemodynamics in vascular and Alzheimer’s dementia. Neurol Res 2006; 28:645–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gommer ED, Martens EG, Aalten P, et al. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and controls: evidence for increased peripheral vascular resistance with possible predictive value. J Alzheimers Dis 2012; 30:805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roher AE, Garami Z, Alexandrov AV, et al. Interaction of cardiovascular disease and neurodegeneration: transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Res 2006; 28:672–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roher AE, Garami Z, Tyas SL, et al. Transcranial doppler ultrasound blood flow velocity and pulsatility index as systemic indicators for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7:445–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silvestrini M, Pasqualetti P, Baruffaldi R, et al. Cerebrovascular reactivity and cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer disease. Stroke 2006; 37:1010–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silvestrini M, Vernieri F, Pasqualetti P, et al. Impaired cerebral vasoreactivity and risk of stroke in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA 2000; 283:2122–2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roher AE, Esh C, Rahman A, et al. Atherosclerosis of cerebral arteries in Alzheimer disease. Stroke 2004; 35:2623–2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA 1995; 273:1421–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators, Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Peerless SJ, Ferguson GG, Fox AJ, Rankin RN, Hachinski VC, Wiebers DO, Eliasziw M. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Jackson DC, Mitchell CC, et al. Estimation of ultrasound strain indices in carotid plaque and correlation to cognitive dysfunction. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2014; 5627–5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Jackson DC, Mitchell CC, et al. Classification of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with and without cognitive decline using non-invasive carotid plaque strain indices as biomarkers. Ultrasound Med Biol 2016; 42:909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Jackson DC, Varghese T, et al. Correlation of cognitive function with ultrasound strain indices in carotid plaque. Ultrasound Med Biol 2014; 40:78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Mitchell CC, Varghese T, et al. Improved correlation of strain indices with cognitive dysfunction with inclusion of adventitial layer with carotid plaque. Ultrason Imaging 2016; 38:194–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson DC, Sandoval-Garcia C, Rocque BG, et al. Cognitive deficits in symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid endarterectomy surgical candidates. Arch of Clin Neuropshycol 2016; 31:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benton AL, Hamsher KD and Sivan AB. Multilingual Aphasia Examination: manual of instruction. Iowa City, Iowa: AJA Associates, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ober BA, Dronkers NF, Koss E, Delis DC, Friedland RP. Retrieval from semantic memory in Alzheimer-type dementia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1986; 8:75–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 4th ed. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexander MP, Stuss DT and Fansabedian N. California verbal learning test: performance by patients with focal frontal and non-frontal lesions. Brain 2003; 126:1493–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandt J and Benedict RHB. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: professional manual. Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers JE and Meyers KR. Rey Complex Figure Test and Recognition Trial: professional manual. Odessa, Texas: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natus Neurology Inc. SONARA® Systems and SONARA/tek® Systems User Manual. Middleton, WI: Natus Neurology Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormick M, Varghese T, Wang X, Mitchell C, Kliewer MA, Dempsey RJ. Methods for robust in vivo strain estimation in the carotid artery. Phys Med Biol 2012; 57:7329–7353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meshram NH, Varghese T, Mitchell CC, et al. Quantification of carotid artery plaque stability with multiple region of interest based ultrasound strain indices and relationship with cognition. Phys Med Biol 2017; 62:6341–6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meshram NH and Varghese T. GPU accelerated multilevel Lagrangian carotid strain imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2018; 65:1370–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dempsey RJ, Jackson DC, Wilbrand SM, et al. The preservation of cognition 1 year after carotid endarterectomy in patients with prior cognitive decline. Neurosurgery 2018; 82:322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dempsey RJ, Varghese T, Jackson DC, et al. Carotid atherosclerotic plaque instability and cognition determined by ultrasound-measured plaque strain in asymptomatic patients with significant stenosis. J Neurosurg 2018; 128:111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dempsey RJ, Vemuganti R, Varghese T, Hermann BP. A review of carotid atherosclerosis and vascular cognitive decline. Neurosurgery 2010; 67:484–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant EG, Benson CB, Moneta GL, et al. Carotid artery stenosis: gray-scale and Doppler US diagnosis--Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference. Radiology 2003; 229:340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolaides AN, Shifrin EG, Bradbury A, et al. Angiographic and duplex grading of internal carotid stenosis: can we overcome the confusion? J Endovasc Surg 1996; 3:158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salem MK, Bown MJ, Sayers RD, et al. Identification of patients with a histologically unstable carotid plaque using ultrasonic plaque image analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014; 48:118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabayan B, Jansen S, Oleksik AM, et al. Cerebrovascular hemodynamics in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: A meta-analysis of transcranial Doppler studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11:271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kidwell CS, el-Saden S, Livshits Z, Martin NA, Gleen TC, Saver JL. Transcranial Doppler pulsatility indices as a measure of diffuse small-vessel disease. J Neuroimaging 2001; 11:229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandani A, Bleletsky v, Tamayo A, Munoz C, Spence JD. High-risk asymptomatic carotid stenosis ulceration on 3D ultrasound vs TCD microemboli. Neurology 2011:744–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinciguerra L, Lanza G, Puglisi V, et al. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound in vascular cognitive impairment-no dementia. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0216162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen WH, Jin W, Lyu PY, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis and cognitive impairment in nonstroke patients. Chin Med J 2017; 130:2375–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iadecola C The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 2013; 80:844–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalaria RN. The pathology and pathophysiology of vascular dementia. Neuropharmacology 2018; 134:226–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berman SE, Wang X, Mitchell CC, et al. The relationship between carotid artery plaque stability and white matter ischemic injury. Neuroimage Clin 2015; 9:216–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitchell CC, Wilbrand SM, Kundu B, et al. Transcranial Doppler and microemboli detection: relationships to symptomatic status and histopathology findings. Ultrasound Med Biol 2017; 43:1861–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead Reitan Battery: demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strauss E, Sherman E Spreen O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests (3rd Ed.). New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan EF, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell C, Wilbrand SM, Cook TD, et al. Traditional Doppler Measures Do Not predict Cognition in a Cohort With Advanced Atherosclerosis. Stroke. 50:Suppl_1 abstract WMP47. [Google Scholar]