ELKS1 controls mast cell degranulation by regulating the transcription of Stxbp2 and Syntaxin 4 via Kdm2b stabilization.

Abstract

ELKS1 is a protein with proposed roles in regulated exocytosis in neurons and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling in cancer cells. However, how these two potential roles come together under physiological settings remain unknown. Since both regulated exocytosis and NF-κB signaling are determinants of mast cell (MC) functions, we generated mice lacking ELKS1 in connective tissue MCs (Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre) and found that while ELKS1 is dispensable for NF-κB–mediated cytokine production, it is essential for MC degranulation both in vivo and in vitro. Impaired degranulation was caused by reduced transcription of Syntaxin 4 (STX4) and Syntaxin binding protein 2 (Stxpb2), resulting from a lack of ELKS1-mediated stabilization of lysine-specific demethylase 2B (Kdm2b), which is an essential regulator of STX4 and Stxbp2 transcription. These results suggest a transcriptional role for active-zone proteins like ELKS1 and suggest that they may regulate exocytosis through a novel mechanism involving transcription of key exocytosis proteins.

INTRODUCTION

The transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is a master regulator of inflammation and many other physiological processes (1–5). Activation of NF-κB by more than 500 physiological stimuli is reliant on the stimulus-dependent activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex (1, 3). Given that inflammation is the underlying cause of many human ailments, blocking unwanted activity of the IKK complex has been a major focus of academic laboratories and pharmaceutical companies (1, 2). To this end, identification of the proteins that constitute and regulate the IKK complex has been a major effort through the past two decades (6). ELKS1 (also known as ERC1 or Rab6IP2) was identified using mass spectrometry as an essential component of the IKK complex and was implicated in the activation of NF-κB pathway in response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling (7). Apart from various cell-surface receptor–mediated activation pathways, NF-κB can also be activated by DNA damaging agents, which initiate NF-κB activation from the nucleus. ELKS1 was found to regulate DNA damage-induced NF-κB activation via binding to K-63 ubiquitin chains (8, 9), a mechanism distinct from that used by ELKS1 to activate NF-κB by stimuli that originate in the cytoplasmic or cellular membranes. Unlike other essential components of the IKK complex such as IKK1, IKK2, and NEMO (mice null for any of these components die around embryonic day 12.5 due to liver apoptosis) (10), the physiological role of ELKS1 in regulating NF-κB and inflammation has not been documented, largely due to very early embryonic lethality of ELKS1 whole-body knockout (KO) mice (11). In vivo roles of ELKS1 have confounded the dissection of its physiological functions in NF-κB activation and inflammation. One such role of ELKS1 is its importance in organizing the presynaptic active zones of neurons, wherein it plays a critical structural role in calcium-dependent release of neurotransmitters, a process of regulated exocytosis (12). Regulated exocytosis is a conserved process in which the membranes of cytoplasmic organelles fuse with the plasma membrane to secrete specific products that are segregated in the organelle lumen to the extracellular space in response to stimuli (13, 14). Deletion of ELKS1 in cultured hippocampal neurons after synapse establishment was shown to result in impaired neurotransmitter release at inhibitory synapses and reduction in single action potential–triggered Ca2+ influx at inhibitory nerve terminals (11). Together with other active zone proteins, such as regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis 1 (RIM1), Munc13-1, bassoon presynaptic cytomatrix protein (Bassoon), and Liprin-α, ELKS1 has been shown to mediate the exocytosis of neurotransmitters by presynaptic neurons (15). ELKS1 was also implicated in exocytosis processes in many different cell types besides presynaptic neurons (16–20). For instance, Ohara-Imaizumi et al. (20) showed that pancreatic β cell–specific ELKS1-KO mice had reduced first-phase insulin secretion after glucose stimulation in vivo and showed that ELKS1 directly interacted with the voltage-dependent calcium channel to mediate insulin secretion. Another study by Nomura et al. (17) demonstrated that knockdown of ELKS1 by small interfering RNA in RBL-2H3 (rat basophilic leukemia cell line) resulted in diminished degranulation, whereas overexpression of ELKS1 in these cells led to a significantly enhanced degranulation, suggesting a general role of ELKS1 in regulated exocytosis. Given these confounding factors and the very early embryonic lethality of ELKS1 null mice, in which cell type do we test the physiological roles of ELKS1 in inflammation and NF-κB signaling?

Mast cells (MCs) are innate immune cells that have the high-affinity receptors for immunoglobulin E (IgE), FcεRI, and therefore are considered the major effector cells of type I hypersensitivity reactions (21). MCs reside throughout the body but are particularly abundant in barrier tissues such as the skin and mucosae where they are involved in protection against pathogens and parasites and support wound healing (21, 22). The cytoplasm of MCs contains preformed secretory granules that store potent bioactive molecules, e.g., histamine, tryptase, chymase, and enzymes such as β-hexosaminidase (21, 23, 24). Cross-linking of the FcεRI on MCs initiated by binding of IgE plus antigen is an imminent signal for the regulated exocytosis of preformed secretory granules (early-phase response) (21, 23–25). Hours after stimulation, MCs also de novo synthesize an array of cytokines and chemokines mediated by NF-κB transcription factors (23), and these cytokines and chemokines are secreted through constitutive exocytosis (late-phase response) (21–25). Both of these phases of IgE-induced responses in MCs must be tightly regulated as aberrant early- and late-phase responses are key events in the pathogenesis of allergic diseases (21). Although ELKS1 has previously been suggested to regulate degranulation in the RBL-2H3 cell line, which shows MC-like characteristics (17), the physiological role of ELKS1 in MC function and response, if any, has not been studied in vivo thus far. Furthermore, since ELKS1 has also been proposed to regulate NF-κB signaling in several human cancer cell lines (7), it is unclear whether ELKS1 is involved in regulating both early and late responses in primary MCs. Since MCs undergo both early (degranulation) and late (NF-κB–mediated cytokine transcription) responses upon FcεRI-mediated activation, MCs provide us with a unique system to investigate the proposed functions of ELKS1 in regulated exocytosis and NF-κB–mediated inflammatory response within the same cell type simultaneously. To analyze the physiological role of ELKS1, we generate MC-specific deletion of ELKS1 using Mcpt5-Cre mice. We show that active zone proteins like ELKS1 can regulate exocytosis through a novel mechanism involving transcription of other key exocytosis proteins. The role of ELKS1 in the active zones of neurons is largely considered to be that of a structural protein that holds the other proteins together. Our findings, which depart from the current view largely based on studies from neurons, could be immensely useful to (i) further evaluate whether ELKS1 can also regulate transcription of other active zone proteins in most secretory cells and (ii) assess whether other active zone proteins also work by transcriptionally regulating key components of the secretory machinery in cells where exocytosis is regulated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Generation and characterization of mice with MC-specific deletion of ELKS1

To investigate the in vivo role(s) of ELKS1 specifically in MCs, we generated mice bearing MC-specific deletion of ELKS1 (Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice) by crossing Elks1f/f mice (11) with mice expressing the Cre recombinase under the control of the MC protease 5 promoter (Mcpt5-Cre mice), which drives Cre transcription predominantly in the skin and peritoneal cavity MCs (fig. S1, A and B) (26). Unlike whole-body deletion of ELKS1, which results in embryonic lethality (11), Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice did not result in embryonic lethality (fig. S1C). Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice exhibited normal gross physiology and were born in Mendelian ratios (fig. S1C). Mcpt5-Cre is known to efficiently inactivate genes in connective tissue MCs such as skin-resident MCs but not in mucosal type MCs (27). Therefore, we isolated peritoneal cells from Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice and Elks1f/f littermate controls and cultured and expanded them into peritoneal cell–derived MCs (PCMCs), which are mature MCs that retain the key functional and phenotypic features of the parent cells in vivo (28). We confirmed that Mcpt5-Cre efficiently depletes ELKS1 in PCMCs, both at mRNA and protein levels (fig. S1, D and E). However, Mcpt5-Cre is less efficient in deleting ELKS1 in bone marrow–derived MCs (BMMCs) (fig. S2, A and B), in line with the previous literature showing that the connective tissue MCs but not mucosal MCs were efficiently depleted in the small intestine and stomach of Mcpt5-Cre+ iDTR+ mice (27). ELKS1 deficiency did not impair the proliferation of PCMCs (fig. S1F) nor affect the purity of both cultured PCMCs and BMMCs (fig. S1G and fig. S2C).

ELKS1 positively regulates IgE-mediated degranulation but not inflammatory cytokine gene expression in PCMCs

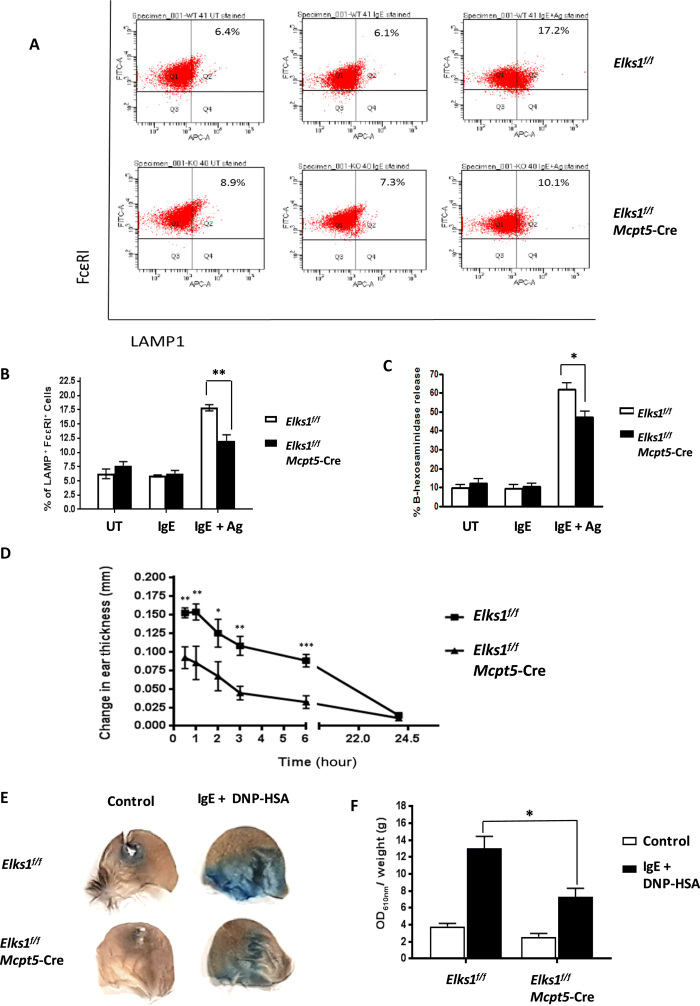

To study the roles of ELKS1 in PCMCs, we first tested whether ELKS1 deficiency leads to any defects in IgE-mediated degranulation. To this end, we sensitized PCMCs with anti-dinitrophenyl (DNP) IgE overnight and then activated them with DNP–bovine serum albumin (BSA). We next measured the proportion of PCMCs within the Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control populations with cell-surface lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1 or CD107a) which indicates granule movement to the plasma membrane. Upon DNP-BSA–mediated activation, Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs had significantly less cell-surface LAMP1 staining compared to Elks1f/f control PCMCs, suggesting a critical role of ELKS1 in the degranulation process (Fig. 1, A and B). Consistent with this, release of β-hexosaminidase enzyme located in MC secretory granules was significantly reduced in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs upon DNP-BSA stimulation (Fig. 1C). Since ELKS1 has previously been shown to be involved in NF-κB activation by TNFα (7), we then investigated whether ELKS1 deficiency leads to any defect in activation-induced transcription of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines. However, unlike with degranulation, we observed no significant differences in the transcriptional induction of NF-κB–dependent inflammatory genes such as TNFα, interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL1), and CCL2 between Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs (fig. S2D). We also observed comparable dynamics in the activation of several signal transduction pathways such as p38, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and NF-κB known to be involved in de novo mediator synthesis in MCs between Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs (fig. S2E). Note that cytokine response and degranulation are independent events, as shown in numerous other studies (29–32). The role of different IKK complex subunits, including IKK2 and NEMO in MC functions, has been implicated in the study by Peschke et al. (32), which showed no difference in MC degranulation ex vivo and immediate phase anaphylactic [passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA)] response in vivo between IKK2f/f (WT) mice and IKK2f/f Mcpt5-Cre (IKK2-KO) mice. However, both IKK2 and NEMO were important for cytokine transcription and translation in PCMCs ex vivo, and mice lacking IKK2 or NEMO in their connective tissue MCs had impaired late-phase response due to reduced MC-derived pro-inflammatory cytokines after allergen challenge in vivo (32). Similarly, previous finding by Suzuki and Verma (33) demonstrated defect in late-phase allergic reactions in IKK2-KO MC-reconstituted, MC-deficient WBB6F1-Kitw/Kitw-v (W/Wv) mice as compared to WT MC-reconstituted W/Wv mice in vivo. In this study, using the Mcpt5-Cre mice to specifically delete ELKS1 in PCMCs, we find that ELKS1 regulates FcεRI-induced degranulation but not transcription of cytokines and chemokines in MCs. In agreement with the findings from Peschke et al. (32), which shows that IKK complex regulates only late responses in MCs, we believe that ELKS1 has no IKK complex–dependent role in NF-κB activation in MCs, and functional association of ELKS1 with IKKs is restricted to contexts such as DNA damage (9), which activate NF-κB via a very distinct mechanism (34).

Fig. 1. ELKS1 is required for MC degranulation.

(A) PCMCs derived from Elks1f/f and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice, respectively, were sensitized with anti–DNP-IgE (0.5 μg/ml) overnight and stimulated with DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml) for 30 min. Degranulation was assessed by cell-surface LAMP1 and FcεRI expressions using flow cytometry. Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 3; **P < 0.01. (B) Bar chart representation of flow cytometry results from (A). (C) Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs were sensitized with anti–DNP-IgE (0.5 μg/ml) overnight and stimulated with DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml) for 1 hour. Degranulation was assessed by beta-hexosaminidase release assay. Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 5; *P < 0.05. (D) Elks1f/f and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice were intradermally injected with anti–DNP-IgE (SPE-7, 100 ng) in the right ear pinna and an equal volume of HMEM-Pipes vehicle in the left ear pinna. Sixteen hours later, DNP-HSA (200 μg in 100 μl) was intravenously injected, and the increase in ear thickness was recorded at intervals between 0 and 24 hours later. n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. (E) Evans blue dye extravasation from ear of Elks1f/f and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice 30 min after intravenous DNP-HSA (containing 1% Evans blue) administration. Picture showing ear pinnae of Elks1f/f and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice. (F) Evans blue dye extravasation from (E) was quantified by an optical density at 610 nm (OD610nm)/weight. n = 3; *P < 0.05. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; APC-A, allophycocyanin-A; UT, untreated.

Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice show impaired anaphylactic response in vivo

To investigate the in vivo role of ELKS1 in MC responses, we studied PCA response in a cohort of control and ELKS1-KO mice. To this end, we sensitized Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control mice by intradermally injecting DNP-IgE into their ear pinnae. One day later, we induced MC activation by tail vein injection of DNP–human serum albumin (HSA). In line with our ex vivo results, control mice exhibited marked increases in ear thickness in the hours following DNP-HSA injection, indicating the release of preformed mediators from skin-resident MCs, while the ears of Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice swelled significantly less (Fig. 1D). Similarly, after DNP-HSA injection, the extravasation of Evan’s blue dye was significantly less in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice compared to controls, indicating reduced vascular leakage in the absence of ELKS1 (Fig. 1, E and F). However, there were comparable numbers of skin-resident MCs in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control mice, as determined by toluidine blue staining of their ear skin tissue (fig. S3A), suggesting that the observed differences in PCA were not due to a reduction in MC numbers in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice. Together, ELKS1 is necessary for normal skin MC degranulation in response to DNP-HSA injection in these mice.

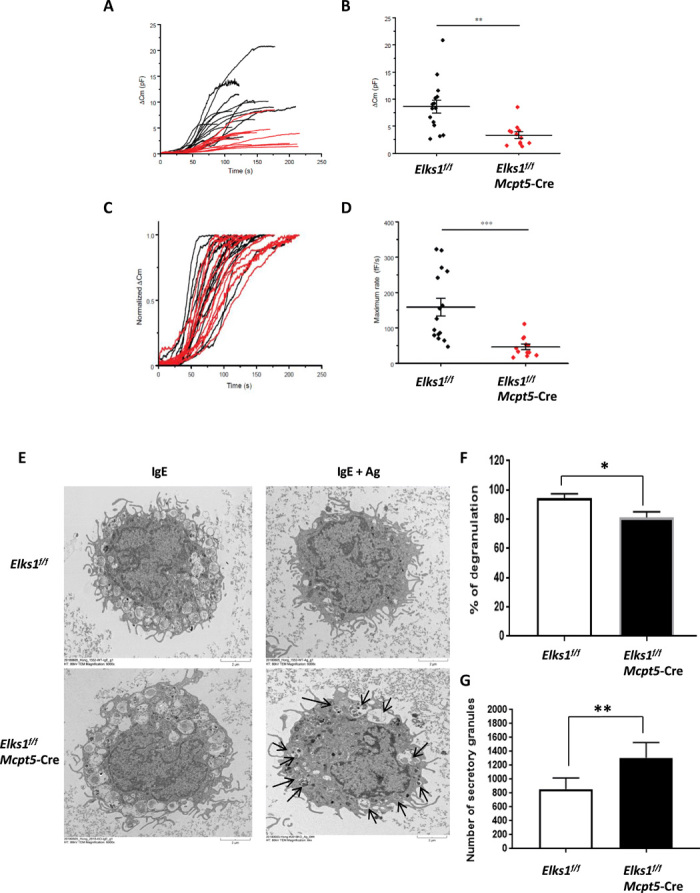

ELKS1 regulates the fusion of secretory granules with the plasma membrane

Having seen the effects of ELKS1 on MCs at the population and organism levels, we next examined the underlying process at the single MC level. We took individual PCMCs and conducted patch-clamp experiments to measure changes in membrane capacitance (Cm), which increases when secretory vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane during exocytosis (35, 36). We observed that after intracellular dialysis of guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTP-γ-S) and calcium (Ca2+) through the patch pipette, both the cumulative Cm change (ΔCm) and the amplitude of ΔCm were significantly reduced in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs by about 50% as compared to Elks1f/f control PCMCs (Fig. 2, A and B). We then normalized the ΔCm to calculate the maximum rate of exocytosis (a rate between 40 and 60% of total ΔCm) (Fig. 2C), corresponding to the steepest part of each curve of Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs (Fig. 2D). These calculations show that, besides having less total exocytosis (Fig. 2, A and B), Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs have a significantly slower rate of degranulation than Elks1f/f control PCMCs (Fig. 2, C and D). Therefore, these results suggested that ELKS1 positively regulates the amount and rate of secretory vesicles fusion with the plasma membrane in PCMCs. At the ultrastructural level, electron microscopy (EM) of anti–DNP-IgE–sensitized/DNP-BSA–activated PCMCs showed that markedly more secretory granules were retained in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs compared to controls (Fig. 2, E and F). Furthermore, we saw that Elks1f/fMcpt5-Cre PCMCs also harbored more secretory granules when unstimulated (Fig. 2G), suggesting that the absence of ELKS1 induced a defect in secretion of granules, not in their generation. Together, these results from electrophysiology and EM reiterate that ELKS1 is a positive regulator of MC degranulation and that defective degranulation in the absence of ELKS1 has physiological consequences (Fig. 1, D to F).

Fig. 2. ELKS1 regulates the extent and rate of MC degranulation.

(A) Raw traces show the cumulative Cm from Elks1f/f control (black) and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs (red). Total ΔCm was recorded from Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs until it reached the maximum with intracellular dialysis of GTP-γ-S and Ca2+. Whole-cell mode was done at time 0 (control, n = 15, black; Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre, n = 12, red). (B) Maximum ΔCms were measured from Elks1f/f control (black) (8.61 ± 1.23 pF) and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre (in red) (3.36 ± 0.58 pF). (C) ΔCms were normalized to estimate the rate of degranulation from the same traces of (A). (D) The maximum degranulation rate was quantified from Elks1f/f control (black) and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs (red). The averaged maximum rate was estimated between 40 and 60% of maximum ΔCm in Elks1f/f control (158.73 ± 25.27 fF/s) and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre (46.24 ± 7.99fF/s) PCMCs. Statistical analyses were conducted using two-way t test, and P values are represented by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). (E) PCMCs derived from Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control mice were sensitized with anti–DNP-IgE (0.5 μg/ml) overnight, stimulated with DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml) for 30 min, and analyzed by EM. Scale bars, 2 μm. Images showing the secretory granules within the Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs with or without anti–DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA stimulation. Solid arrows pointing at secretory granules retained within the Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMC after stimulation. (F) The number of secretory granules were counted in each EM picture, and percentage of degranulation was calculated (as described in Materials and Methods) and plotted (i.e., percentage of degranulation = 100% indicates that no secretory granule is retained in the MC after stimulation). Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 3; *P < 0.05. (G) The number of secretory granules in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs without stimulation was counted in EM images. Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 3; **P < 0.01.

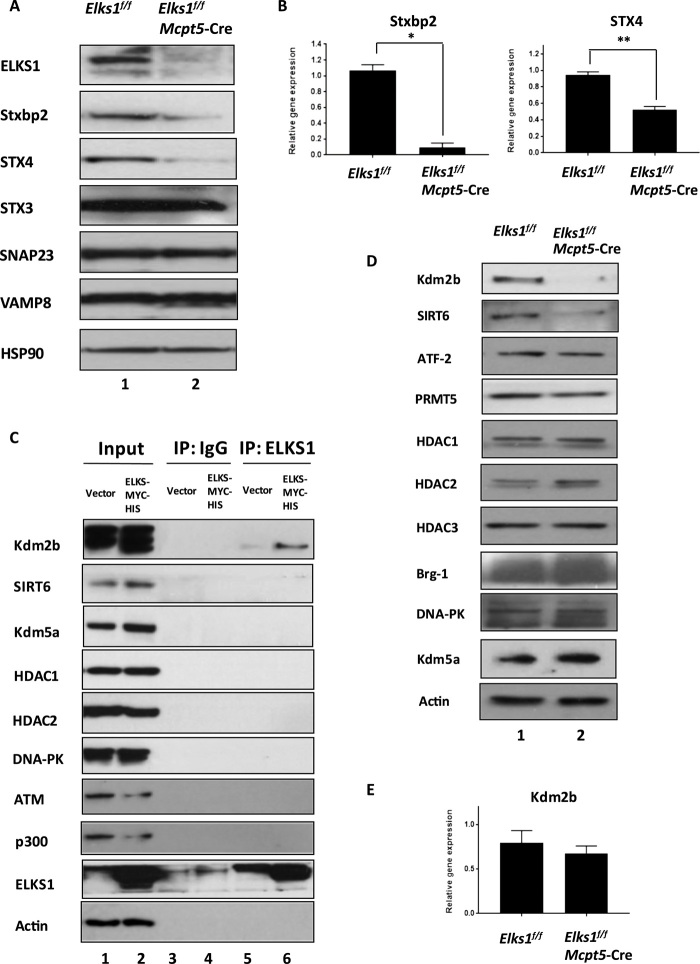

ELKS1 regulates the expression of Stxbp2 and Syntaxin 4 genes

Degranulation is not a spontaneous event, and similar to regulated exocytosis in other cell types (such as the release of neurotransmitters in neurons), it requires the association of soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins, vesicular SNARE (v-SNARE), and target SNARE (t-SNARE) to form a ternary SNARE complex that catalyzes membrane fusion. Members within the SNARE complex vary depending on the cell types (37). In MCs, the t-SNAREs include STX3, STX4, and SNAP23 (37), while the v-SNARE is VAMP8 (30). Sander et al. (38) have previously demonstrated that significantly less histamine was released from FcεRI-stimulated mature MCs isolated from human intestinal tissue after inhibiting these SNARE proteins with neutralizing antibodies, indicating their critical role in MC degranulation. In addition, the formation and function of SNARE complex required for MC degranulation are also regulated by several accessory proteins such as Stxbp2 (39, 40), and Gutierrez et al. (36) demonstrated the failure of regulated exocytosis in Stxbp2-deficient MC ex vivo, accompanied by less systemic anaphylactic response in MC-specific Stxbp2 KO mice, suggesting an indispensable role of Stxbp2 in MC degranulation in vivo. Therefore, we next analyzed whether deletion of ELKS1 alters the protein levels of SNARE complex members, including STX4, VAMP8, SNAP23, and Stxbp2, which are critical for MC degranulation (41). Unexpectedly, unlike in the cultured hippocampal neurons and pancreatic islets where deletion of ELKS1 did not alter the protein expressions of other active zone proteins (11, 20), our Western blot analysis showed specific reduction of Stxbp2 and STX4 proteins in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs compared to Elks1f/f control PCMCs under unstimulated condition (Fig. 3A). These effects were directly mediated by the lack of ELKS1, as ectopic ELKS1 expression enhanced the expressions of Stxbp2 and STX4 (fig. S3C). Unexpectedly, the reduction in protein levels of Stxbp2 and STX4 was also paralleled by reduced levels of mRNA for these genes in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs (Fig. 3B). These results hinted that ELKS1-mediated control of Stxbp2 and STX4 proteins in MC could be a result of transcriptional changes of Stxbp2 and STX4 genes, possibly regulated by ELKS1. Although several lines of evidence have previously shown that ELKS1 is crucial for the regulated exocytosis process via direct interaction with Bassoon, Piccolo, and RIM1 and indirect interaction with Munc13-1 to promote the assembly of the active zone in neuronal cells (42–44), while ELKS1 involves in the insulin secretion through directly interacting with voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels at the vascular side of the β cell plasma membrane (20), ELKS1 has been shown to control gene transcription of SNARE proteins in MCs in this study.

Fig. 3. ELKS1 regulates Stxbp2 and Syntaxin 4 expressions.

(A) Western blot analysis showing the protein levels of Stxbp2, STX4, SNAP23, VAMP8, STX3, and ELKS1 in PCMCs derived from Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control mice, respectively. HSP90 was used as a loading control (representative of three mice from each group). (B) Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of Stxbp2 and STX4 mRNA expressions in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs. Values were normalized to β-actin expression levels and then to levels in Elks1f/f MCs. Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 3; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. (C) Ectopic expression of ELKS-MYC-HIS in HEK-293T cells and immunoprecipitation (IP) of ELKS1 with lysate probing using the indicated antibodies. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Western blot analysis of the protein levels of chromatin remodelers in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs. β-Actin was used as a loading control (representative of three mice from each group). (E) RT-PCR analysis of Kdm2b expression in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs. Values were normalized to β-actin expression levels and then to levels in Elks1f/f MCs. Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 3.

ELKS1 binds to Kdm2b and inhibits ubiquitination of Kdm2b, which controls the expression of Stxbp2 and STX4

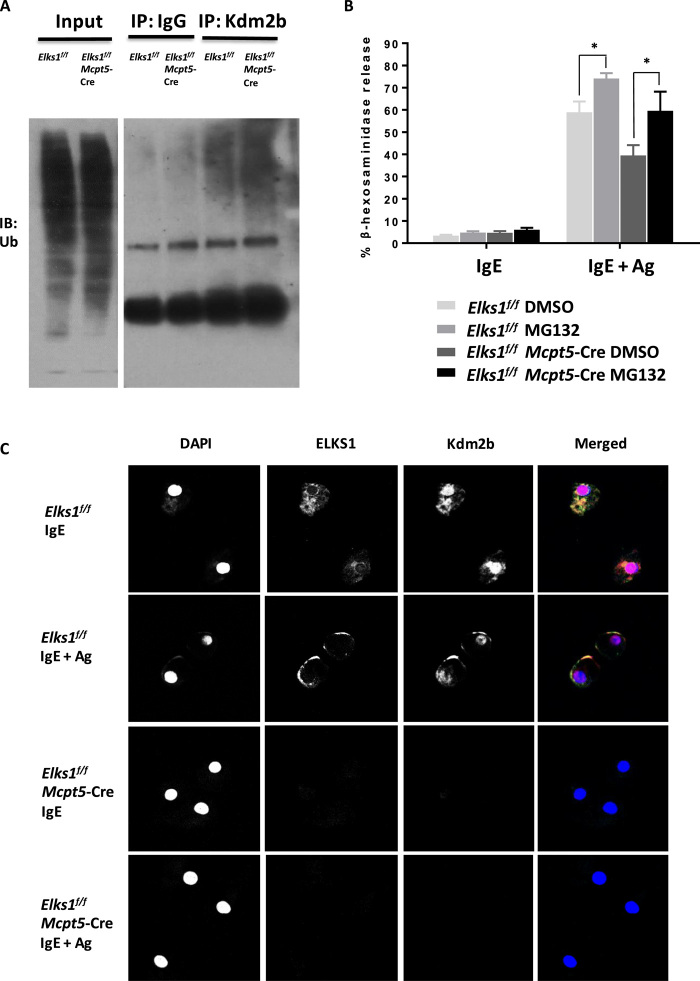

We then asked how ELKS1 could be regulating SNARE complex protein gene transcription in cells. We first ectopically expressed ELKS1-MYC-HIS in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK-293T) cells and carried out immunoprecipitation to screen for interactions between ELKS1 and a panel of chromatin remodelers (Fig. 3C). Ectopic ELKS1 was found to specifically associate with endogenous Kdm2b, and ectopic expression of ELKS1 led to up-regulated expressions of Kdm2b, SIRT6, and Kdm5a (Fig. 3C). Detection of endogenous ELKS1 and endogenous Kdm2b interaction was weak due to existing reagents. In reverse, when we conducted immunoprecipitation with Kdm2b, we again detected ELKS1 as a specific interaction partner (fig. S3D), confirming this interaction. Having identified Kdm2b as ELKS1 interaction partner in HEK-293T cells, we measured its protein expression level in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs and found it to be much lower comparing to Elks1f/f control cells (Fig. 3D). The protein level of SIRT6 was also much lower in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs compared to control PCMCs, while the levels of the other chromatin remodelers tested were comparable between Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs and control PCMCs (Fig. 3D). There is no significant difference in the gene expression levels of Kdm2b, SIRT6, and Kdm5a between Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs (Fig. 3E and fig. S3B), suggesting that ELKS1 might stabilize the protein levels of a few key chromatin regulators, and investigation into this role of ELKS1 will be important for future studies. In HEK-293T cells, ELKS1 has been shown to interact with ubiquitin following genotoxic stress (8, 9); therefore, we hypothesized that ELKS1 may protect Kdm2b from degradation perhaps via blocking its ubiquitination. BMMCs derived from Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice had enhanced ubiquitination of Kdm2b as compared to Elks1f/f control BMMCs (Fig. 4A), and blocking ubiquitination with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 rescued the reduced Kdm2b protein level in Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs (fig. S4A). In addition, blocking ubiquitination with MG132 before DNP-BSA stimulation of PCMCs significantly enhanced degranulation (Fig. 4B). Since the reduced Kdm2b levels in ELKS1-deficient PCMCs were rescued by MG132, this would suggest that at least K-48 polyubiquitin chains are involved in its modification as they have been implicated in proteasomal degradation (45). Using computational analysis, we predicted that several E3 ubiquitin ligases might interact with Kdm2b (table S1). Hence, ELKS1 might inhibit the ubiquitination of Kdm2b through blocking the binding of E3 ligase to Kdm2b. However, further experiments are required to verify the exact E3 ligase(s) involved and also to determine whether ELKS1 promotes deubiquitination of Kdm2b in addition to blocking the K-48 ubiquitination of Kdm2b. Together, these results suggest that ELKS1 interacts with Kdm2b to block its ubiquitination and that Kdm2b may directly or indirectly control the gene expression of STX4 and Stxbp2, which eventually regulates MC degranulation.

Fig. 4. Loss of ELKS1 leads to enhanced Kdm2b ubiquitination.

(A) Immunoprecipitation of Kdm2b (or IgG control) followed by Western blot analysis for ubiquitination (Ub) using Elks1f/f and Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre–derived BMMCs. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs were sensitized with anti–DNP-IgE (0.5 μg/ml) overnight and treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (25 μM), or not, for 3 hours before stimulation with DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml) for 1 hour. Degranulation was assessed by beta-hexosaminidase release assay. Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 3; *P < 0.05. (C) Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs were sensitized with anti–DNP-IgE (0.5 μg/ml) overnight and stimulated with DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml) for 15 min before localization of ELKS1 (green), Kdm2b (red), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) were analyzed using confocal microscopy. Representative single optical sections and merged images are shown (63× oil lens, ZEISS LSM800 confocal microscope). IB, immunoblot; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

To further study the role of ELKS1 in membrane fusion and the interaction of ELKS1 with Kdm2b and Stxbp2, we investigated the localization of ELKS1, Kdm2b, and Stxbp2 in PCMCs. Confocal analysis shows that ELKS1 is located in the cytoplasm in unstimulated cells and moves toward the plasma membrane after stimulation with anti–DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA, whereas Kdm2b is localized in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm where it interacts with ELKS1 (Fig. 4C). Stxbp2 is mainly located in the cytoplasm when both unstimulated and stimulated (fig. S4B). Consistent with our previous results in Fig. 3 (A and D), Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre PCMCs had almost undetectable levels of Kdm2b (Fig. 4C) and Stxbp2 (fig. S4B). Together, these results suggest that the presence of ELKS1 blocks ubiquitination of Kdm2b, which, in turn, enables optimal levels of transcription of STX4 and Stxbp2 that are required for MC degranulation.

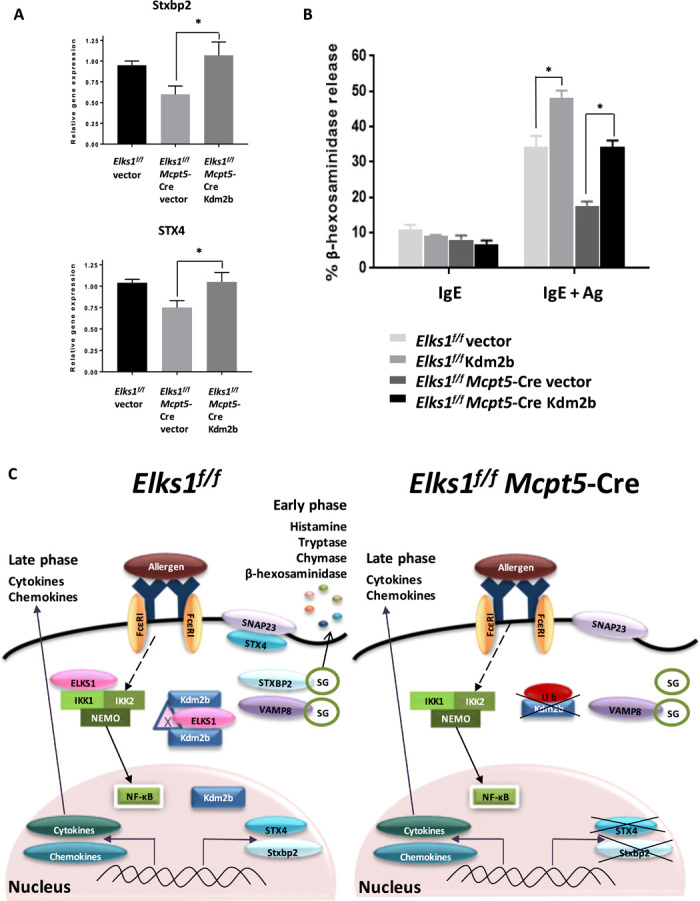

To directly evaluate the role of Kdm2b in regulating transcription of STX4 and Stxbp2 genes, we reconstituted Kdm2b in PCMCs and measured the effects on expression of Stxbp2 and STX4 and degranulation. Reconstitution of Kdm2b restored the transcription of Stxbp2 and STX4 mRNA (Fig. 5A). Reconstitution of Kdm2b also restored MC degranulation, as measured by β-hexosaminidase release following anti–DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA stimulation (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, transcription of Stxbp2 and STX4 was inhibited after PCMCs were treated with pan-selective demethylase inhibitor, JIB-04, a small molecule that specifically inhibits the demethylase activity of the Jumonji family of KDMs (46), including that of Kdm2b (fig. S4C). Kdm2b consists of four functional domains, including the N-terminal JmjC domain that is responsible for the demethylation of H3K36me2, the CxxC zinc-finger domain for DNA binding that specifically recognizes CpG islands, the PHD domain that acts as an E3 ligase or as a histone modification reader domain, and the F-box domain that acts as a linker protein between a target protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase (47). As the JIB-04 inhibitor specifically inhibits the demethylase activity of Kdm2b (46), this might suggest that the JmjC domain of Kdm2b, which is responsible for the H3K36me2 demethylation, is involved in the transcription of Stxbp2 and STX4, and further experiments are needed to confirm this using deletion constructs. Together, these results suggest that ELKS1 might interact with Kdm2b as a signal transducer preceding epigenetic modification that initiates gene transcription of STX4 and Stxbp2, which are required for degranulation in PCMCs. These results also suggest that levels and localization of Kdm2b are regulated by ELKS1 in MCs.

Fig. 5. ELKS1 regulates degranulation in MCs through Kdm2b.

(A) Control PCMCs derived from Elks1f/f mice were transfected with vector (as control), and PCMCs derived from Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice were transfected with vector or Kdm2b, and then mRNA expression of Stxbp2 and STX4 mRNA was analyzed. Values were normalized to β-actin and then to levels in control PCMCs transfected with vector. Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 3; *P < 0.05. (B) Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control PCMCs were derived from Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre and Elks1f/f control mice, respectively, and transfection was performed as indicated in (A). Cells were sensitized with anti–DNP-IgE (0.5 μg/ml) overnight and stimulated with DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml) for 1 hour. Degranulation was assessed by β-hexosaminidase assay. Bar, mean; error bar, SEM. n = 3; *P < 0.05. (C) Model depicting the mechanism of ELKS1 regulation of degranulation in PCMCs. In Elks1f/f control PCMCs, ELKS1 interacts with Kdm2b to protect it from ubiquitination and therefore degradation. This interaction between ELKS1 and Kdm2b might involve an adaptor protein, Protein X. Further experiment will be needed to identify this protein. The presence of Kdm2b in the nucleus enables transcription of Stxbp2 and STX4, which are key proteins for MC degranulation. In the absence of ELKS1 in PCMCs, there is an enhanced ubiquitination and degradation of Kdm2b, which lead to much lower levels of Stxbp2 and STX4 transcription. In this case, the reduced gene and, thereby, protein expressions of Stxbp2 and STX4 result in impaired degranulation in these Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre MCs. Late-phase cytokine response mediated by NF-κB is not affected in these Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre MCs.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Secretion is a universal process in living organisms and is essential for diverse biological processes and functions (14, 48). Secretion can be classified into two main pathways, constitutive exocytosis and regulated exocytosis (14, 48). Constitutive exocytosis is a feature of all eukaryotic cells (14, 48), and newly formed cellular products are secreted with varying rates as they are synthesized (35). On the contrary, regulated exocytosis is used by specialized secretory cells such as neurons for the release of neurotransmitters, pancreatic islet β cells for insulin secretion, and MCs for the release of histamine and other inflammatory molecules (49). During regulated exocytosis, measured number of secretory granules with preformed cellular products undergo complex fusion events with the plasma membrane to release appropriate granular content to the cell exterior upon receiving relevant biochemical or electrical stimulation (35, 41, 48). Dysregulation of regulated exocytosis can lead to diseases, for example, the kinetics of insulin secretion is severely distorted in type 2 diabetes (50), while excessive exocytosis from MCs may result in anaphylaxis (48). Since the regulated exocytosis pathways in different cell types share many common core components, for instance, they all use cytoskeleton proteins for transport of vesicles and the SNARE proteins for membrane fusion (49), understanding the regulated exocytotic machinery in one secretory cell has been used to gain insights into the mechanism of secretion in the other secretory cells. Despite being essential for numerous biological processes, the precise molecular mechanism for regulated exocytosis has not been fully elucidated in MCs. Lessons learnt from the active zones of neurons are used to identify and characterize proteins and events that regulate exocytosis in other cell types including MCs (17, 20).

In conclusion, our study suggests that ELKS1 interacts with the transcriptional regulator Kdm2b in PCMCs. However, in vitro pulldowns with purified recombinant proteins are needed to determine whether this interaction is direct or it might involve other proteins as adaptors for inhibiting Kdm2b ubiquitination or promoting its de-ubiquitination. Our results show that the interaction between ELKS1 and Kdm2b in MCs is required for normal levels of gene transcription of the SNARE components STX4 and Stxbp2, which are required for degranulation in MCs (Fig. 5C). Despite a proposed role for ELKS1 in NF-κB signaling in immortalized tumor cell lines, we find no evidence for this in MCs. More broadly, these data provide further evidence that ELKS1 has context-dependent functions in different cell types: In MCs, ELKS1 is involved in regulated exocytosis, similar to its role in neurons and pancreatic β cells but through a different mechanism, while in the active zone of neuronal cells, it has a scaffolding function; and in cancer cells treated with TNF, it is involved in NF-κB–mediated signaling. In this study, we have identified a previously unknown role of ELKS1. We have demonstrated here that ELKS1 controls the transcription and, thereby, expression of other genes required for regulated exocytosis through maintaining the stability of the chromatin remodeler Kdm2b in MCs. These findings represent a new avenue in the understanding of both ELKS1 function and MC biology, suggesting ELKS1 as a promising therapeutic target in the treatment of allergy, MC degranulation disorders, and autoimmunity. Furthermore, the findings in this study pose several interesting questions for further research: Does ELKS1 also regulate transcription and/or stability of chromatin remodelers or other active zone proteins in immune/other specialized secretory cells? Do other active zone proteins, like ELKS1, also work by transcriptionally regulating key components of the secretory machinery? This knowledge can be applied to better our understanding of allergies, MC degranulation disorders, and autoimmune conditions where dysregulated exocytosis in MCs underpins serious challenges in human health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

We obtained Elks1f/f mice from T. Südhof (Standford University) (11) and Mcpt5-Cre mice from A. Roers (University of Cologne) (26) and crossed them to generate Elks1f/f Mcpt5-Cre mice. Six- to 12-week-old animals of both sexes were used, and littermate Elks1f/f mice were used as controls in all experiments. All studies using Elks1f/f mice and Mcpt5-Cre mice have been approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Biological Resource Centre in Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) and were performed in compliance with the ethical guidelines.

Isolation and culture of PCMCs

Mouse peritoneum was flushed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and peritoneal cells were isolated and cultured in the presence of mouse IL-3 (30 ng/ml) and mouse stem cell factor (SCF; 30 ng/ml) for 3 weeks, as previously described (28). Cell purity was routinely checked with cell-surface staining of FcεR1 and CD117, and >85% of the cells were double positive.

Generation of BMMCs

Bone marrow cells were isolated from mouse femur and tibias and cultured in plastic dishes in the presence of mouse IL-3 (10 ng/ml) and mouse SCF (10 ng/ml) for 6 to 8 weeks. Cell purity was checked with cell-surface staining of FcεR1 and CD117, and >80% of the cells were double positive.

RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 1 × 106 PCMCs with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and purified with column using the Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin RNA Isolation Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. One microgram of the isolated RNA was used for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis with the Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was then performed using the SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and was run on the CFX96tm Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). Experiments were performed in duplicate for each sample, and the mRNA expression was normalized to the β-actin mRNA.

Western blotting

For total protein extraction, cells were washed with cold PBS and resuspended in TOTEX buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.9), 350 mM NaCl, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (v/v) NP-40, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitors]. Protein concentration was quantified with Bradford Dye (Bio-Rad), and 20 to 30 μg of protein were resolved with SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) and blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBST (PBS with Tween 20) for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies (see table S2) were incubated overnight in a cold room on a rotating platform. Membranes were washed with PBST six times, 10 min each. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (see table S3) were incubated at 1:5000 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were washed with PBST six times, 10 min each, and enhanced chemiluminesence reagent was incubated with membrane for 1 min before images were developed in a dark room.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed with lysis buffer [170 mM NaCl, 50 mM tris (pH 8.0), 0.5% (v/v) NP-40, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, and protease inhibitors] and precleaned with 40 μl of protein sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 1 hour at 4°C. Antibodies were added to the precleared lysates and allowed to bind at 4°C overnight. Antibody-antigen complexes were precipitated by the addition of Protein Sepharose slurry for 2 hours at 4°C and then washed with washing buffer [100 nM NaCl, 200 mM tris (pH 8.0), 0.5% (v/v) NP-40, and protease inhibitors] for six times and eluted in 2× SDS sample buffer before subjected to immunoblotting analysis.

Immunofluorescence

10,000 PCMCs were sensitized with anti–DNP-IgE (0.5 μg/ml; clone SPE-7) (Sigma-Aldrich, D8406) overnight. On the next day, cells were washed with PBS and then stimulated with DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml; Life Technologies, A23018) for 30 min or left untreated. Cells were then cytospun (3 min at 800 rpm) onto glass slides using cytocentrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CytoSpin 4) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. After three washes with PBS and three washes with tris buffer [50 mM tris-HCL (pH 7.4)], cells were permeabilized and blocked with 5% BSA (in the tris buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100) for 30 min. Cells were then washed twice with tris buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated overnight with primary antibodies (see table S4) (diluted in tris buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% BSA) at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Unbound primary antibody was removed by washing the slides with tris/Triton X-100 twice followed by tris buffer. Cells were then probed with secondary antibody (see table S5) (diluted in tris buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5%BSA) for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Slides were then washed six times with tris/Triton X-100, then once with tris buffer, and once with distilled water. Cells were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade Mount with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Thermo Fisher Scientific, P36935) and viewed under the ZEISS LSM800 confocal microscope.

Flow cytometry

For cell-surface labeling, cells were washed with cold PBS and incubated with a blocking antibody for 10 min. Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were diluted 1:100 in PBS and incubated with cells on ice for 20 min. Stained cells were washed with PBS and analyzed on BD LSR II.

β-hexosaminidase assay

PCMCs were sensitized with anti–DNP-IgE (0.5 μg/ml) overnight. On the next day, cells were washed with Tyrode’s buffer, seeded in V-shaped 96-well plates, and incubated with DNP-BSA (10 ng/ml) for 1 hour. Supernatant and lysed cell pellet were collected and incubated with p-NAG (p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-D-glucosamide) substrate for 1 hour. Reaction was stopped with 0.2 M glycine (pH 10.7), and absorbance was measured at 405 nm in spectrophotometer. The percentage of degranulation was calculated using optical density (OD) values.

Passive cutaneous anaphylaxis

Mice were intradermally injected with 100 ng (in 20 μl) of anti–DNP-IgE (SPE-7 clone) diluted in HMEM-Pipes in the right ear and 20 μl of HMEM (Hanks’ minimal essential medium)–Pipes vehicle in the left ear. Sixteen hours later, mice were challenged by intravenous injection with 200 μg of DNP-HSA (in 100 μl of 0.9% saline). Ear thickness was measured with digimatic micrometer (Mitutoyo, 293-240-30 MDC-25PX) before and at intervals after intravenous antigen challenge.

For Evans blue dye extravasation experiments, the PCA reaction was carried out, as described above, except that 1% Evans blue dye was also included in the 200 μg of DNP-HSA–specific antigen (in 100 μl of 0.9% saline) during intravenous injection. Thirty minutes after challenge with DNP-HSA (containing 1% Evans blue), mice were euthanized, and whole ear pinnae were collected and weighed. The ear pinnae were diced into pieces in an Eppendorf tube and incubated in 200 μl of formamide overnight at 55°C. The samples were then centrifuged at 16,200g for 10 min. One hundred microliters of supernatant was quantified with a plate reader at OD at 600 nm (51, 52).

Electrophysiology

PCMCs were plated on fibronectin-coated coverslip. The coverslips with cells were transferred to the recording chamber containing external recording solution [136.89 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.493 mM MgCl2, 0.0407 mM MgSO4, 0.441 mM KH2PO4, 0.338 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM Hepes, and 10 mM glucose (pH 7.3); 299 mosm]. Whole-cell recordings were performed with 4- to 6-megohm pipettes coated with a silicone elastomer (Sylgard) and filled with an internal solution contained [135 mM K-gluconate, 7 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM Na2ATP, 0.05 mM Li4GTP-γ-S, 2.5 mM EGTA, 7.5 mM Ca-EGTA mM, and 10 Hepes (pH 7.25); 314 mosm]. Measurements of Cm were made with EPC-10 amplifier controlled by Patch master software (HEKA Elektronik). An 800-Hz sinusoidal, 30-mV peak-to-peak stimulus was applied around a holding potential of −70 mV, and the resultant signal was analyzed using the Lindau-Neher technique to yield Cm and the membrane conductance (Gm) and series conductance (Gs). For each 10-ms sweep, the average value was recorded, yielding a temporal resolution for Cm, Gm, and Gs of ~7 Hz. Cells selected for analysis met the criteria of Gm ≤ 1000 pS and Gs ≥ 40 nS. Total Cm was obtained from recordings of Cm over time, and from the normalized curve, the rates of Cm from 40 to 60% of total Cm were obtained. Individual changes in Cm (Cm differentials) were logged.

Electron microscopy

Cells were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde and 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and embedded in 4% gelatine. Gelatine blocks were then postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, washed in distilled water, and dehydrated in ethanol series and propylenoxide with an overnight en bloc staining with 1% uranyl acetate (in 75% EtOH step). Samples were lastly infiltrated with epoxy resin (EPON), embedded in silicon mound, and polymerized for 3 days at 65°C. Ultrathin (50 nm) sections were cut on UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems) with diamond knife (Diatome), collected on formvar-carbon–coated, 200-mesh copper grids (Pellco), and postcontrasted in uranyl acetate and lead citrate. All samples were analyzed on JEM1010 JEOL EM operating at 80 kV and equipped with bottom-mount SIA model 12C high-resolution full-frame charge-coupled device camera (16 bit, 4K).

Secretory granules were identified by their typical homogeneous and electron-dense core content and scored by manual counting from random equatorial cross sections of cells. Twenty-three to 26 cells were analyzed for each sample. The percentage of degranulation for PCMCs from each mouse was calculated using the following equation: 100 − (mean of secretory granules in IgE/Ag stimulated / mean of secretory granules in IgE sensitized × 100).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Roers for Mcpt5-Cre mice. We thank G. Cildir for the help with the transfer of mice from Duke-NUS to A*STAR at the beginning of the study. We also thank the Advanced Molecular Pathology Laboratory for the help with toluidine blue staining and D. Liebl for the help with EM. We thank A. F. Lopez, G. Cildir, K. H. Yip, and S. Chen for the valuable discussion in the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank L. Robinson of Insight Editing London for the constructive review of the manuscript. Funding: This work was supported by the Singapore National Research Foundation, under its Competitive Research Programme (NRF-CRP17-2017-02), Joint Council Office grant (BMSI/15-800003-SBIC-00E), and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore (A*STAR). H.Y.L. is supported by the SINGA scholarship from A*STAR. Author contributions: V.T. conceived the study. H.Y.L., S.A., H.G.B., C.C.W., and S.J. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. H.Y.L. and V.T. wrote the manuscript with editorial input from all co-authors. Competing interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Bennett J., Capece D., Begalli F., Verzella D., D'Andrea D., Tornatore L., Franzoso G., NF-κB in the crosshairs: Rethinking an old riddle. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 95, 108–112 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begalli F., Bennett J., Capece D., Verzella D., D'Andrea D., Tornatore L., Franzoso G., Unlocking the NF-κB conundrum: Embracing complexity to achieve specificity. Biomedicine 5, 50 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capece D., D'Andrea D., Verzella D., Tornatore L., Begalli F., Bennett J., Zazzeroni F., Franzoso G., Turning an old GADDget into a troublemaker. Cell Death Differ. 25, 640–642 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khattar E., Maung K. Z. Y., Chew C. L., Ghosh A., Mok M. M. H., Lee P., Zhang J., Chor W. H. J., Cildir G., Wang C. Q., Mohd-Ismail N. K., Chin D. W. L., Lee S. C., Yang H., Shin Y.-J., Nam D.-H., Chen L., Kumar A. P., Deng L. W., Ikawa M., Gunaratne J., Osato M., Tergaonkar V., Rap1 regulates hematopoietic stem cell survival and affects oncogenesis and response to chemotherapy. Nat. Commun. 10, 5349 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chew C. L., Conos S. A., Unal B., Tergaonkar V., Noncoding RNAs: Master regulators of inflammatory signaling. Trends Mol. Med. 24, 66–84 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Israël A., The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-κB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000158 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigala J. L. D., Bottero V., Young D. B., Shevchenko A., Mercurio F., Verma I. M., Activation of transcription factor NF-κB requiries ELKS, an IκB kinase regulatory subunit. Science 304, 1963–1967 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Z.-H., Shi Y., Tibbetts R. S., Miyamoto S., Molecular linkage between the kinase ATM and NF-κB signaling in response to genotoxic stimuli. Science 311, 1141–1146 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Z.-H., Wong E. T., Shi Y., Niu J., Chen Z., Miyamoto S., Tergaonkar V., ATM- and NEMO-dependent ELKS ubiquitination coordinates TAK1-mediated IKK activation in response to genotoxic stress. Mol. Cell 40, 75–86 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Donato J. A., Mercurio F., Karin M., NF-κB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 246, 379–400 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C., Bickford L. S., Held R. G., Nyitrai H., Südhof T. C., Kaeser P. S., The active zone protein family ELKS supports Ca2+ influx at nerve terminals of inhibitory hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 34, 12289–12303 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Südhof T. C., The presynaptic active zone. Neuron 75, 11–25 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chieregatti E., Meldolesi J., Regulated exocytosis: New organelles for non-secretory purposes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 181–187 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W.-h., Probes for monitoring regulated exocytosis. Cell Calcium 64, 65–71 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Held R. G., Kaeser P. S., ELKS active zone proteins as multitasking scaffolds for secretion. Open Biol. 8, 170258 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue E., Deguchi-Tawarada M., Takao-Rikitsu E., Inoue M., Kitajima I., Ohtsuka T., Takai Y., ELKS, a protein structurally related to the active zone protein CAST, is involved in Ca2+−dependent exocytosis from PC12 cells. Genes Cells 11, 659–672 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nomura H., Ohtsuka T., Tadokoro S., Tanaka M., Hirashima N., Involvement of ELKS, an active zone protein, in exocytotic release from RBL-2H3 cells. Cell. Immunol. 258, 204–211 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grigoriev I., Yu K. L., Martinez-Sanchez E., Serra-Marques A., Smal I., Meijering E., Demmers J., Peränen J., Pasterkamp R. J., van der Sluijs P., Hoogenraad C. C., Akhmanova A., Rab6, Rab8, and MICAL3 cooperate in controlling docking and fusion of exocytotic carriers. Curr. Biol. 21, 967–974 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Astro V., Chiaretti S., Magistrati E., Fivaz M., de Curtis I., Liprin-α1, ERC1 and LL5 define polarized and dynamic structures that are implicated in cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 127, 3862–3876 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohara-Imaizumi M., Aoyagi K., Yamauchi H., Yoshida M., Mori M. X., Hida Y., Tran H. N., Ohkura M., Abe M., Akimoto Y., Nakamichi Y., Nishiwaki C., Kawakami H., Hara K., Sakimura K., Nagamatsu S., Mori Y., Nakai J., Kakei M., Ohtsuka T., ELKS/voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel-β subunit module regulates polarized Ca2+ influx in pancreatic β cells. Cell Rep. 26, 1213–1226.e7 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galli S. J., Tsai M., Mast cells in allergy and infection: Versatile effector and regulatory cells in innate and adaptive immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 1843–1851 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cildir G., Pant H., Lopez A. F., Tergaonkar V., The transcriptional program, functional heterogeneity, and clinical targeting of mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 214, 2491–2506 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam H. Y., Tergaonkar V., Ahn K. S., Mechanism of allergen specific immunotherapy on allergic rhinitis and food allergies. Biosci. Rep. 40, BSR20200256 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monticelli S., Leoni C., Epigenetic and transcriptional control of mast cell responses. F1000Res. 6, 2064 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cildir G., Toubia J., Yip K. H., Zhou M., Pant H., Hissaria P., Zhang J., Hong W., Robinson N., Grimbaldeston M. A., Lopez A. F., Tergaonkar V., Genome-wide analyses of chromatin state in human mast cells reveal molecular drivers and mediators of allergic and inflammatory diseases. Immunity 51, 949–965.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scholten J., Hartmann K., Gerbaulet A., Krieg T., Müller W., Testa G., Roers A., Mast cell-specific Cre/loxP-mediated recombination in vivo. Transgenic Res. 17, 307–315 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudeck A., Dudeck J., Scholten J., Petzold A., Surianarayanan S., Köhler A., Peschke K., Vöhringer D., Waskow C., Krieg T., Müller W., Waisman A., Hartmann K., Gunzer M., Roers A., Mast cells are key promoters of contact allergy that mediate the adjuvant effects of haptens. Immunity 34, 973–984 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malbec O., Roget K., Schiffer C., Iannascoli B., Dumas A. R., Arock M., Daëron M., Peritoneal cell-derived mast cells: An in vitro model of mature serosal-type mouse mast cells. J. Immunol. 178, 6465–6475 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y. J., Chen W., Carrigan S. O., Chen W.-M., Roth K., Akiyama T., Inoue J.-i., Marshall J. S., Berman J. N., Lin T.-J., TRAF6 specifically contributes to FcϵRI-mediated cytokine production but not mast cell degranulation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32110–32118 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tiwari N., Wang C.-C., Brochetta C., Ke G., Vita F., Qi Z., Rivera J., Soranzo M. R., Zabucchi G., Hong W., Blank U., VAMP-8 segregates mast cell-preformed mediator exocytosis from cytokine trafficking pathways. Blood 111, 3665–3674 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Föger N., Jenckel A., Orinska Z., Lee K.-H., Chan A. C., Bulfone-Paus S., Differential regulation of mast cell degranulation versus cytokine secretion by the actin regulatory proteins Coronin1a and Coronin1b. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1777–1787 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peschke K., Weitzmann A., Heger K., Behrendt R., Schubert N., Scholten J., Voehringer D., Hartmann K., Dudeck A., Schmidt-Supprian M., Roers A., IκB kinase 2 is essential for IgE-induced mast cell de novo cytokine production but not for degranulation. Cell Rep. 8, 1300–1307 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki K., Verma I. M., Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 by IκB kinase 2 regulates mast cell degranulation. Cell 134, 485–495 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyamoto S., Nuclear initiated NF-κB signaling: NEMO and ATM take center stage. Cell Res. 21, 116–130 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodarte E. M., Ramos M. A., Davalos A. J., Moreira D. C., Moreno D. S., Cardenas E. I., Rodarte A. I., Petrova Y., Molina S., Rendon L. E., Sanchez E., Breaux K., Tortoriello A., Manllo J., Gonzalez E. A., Tuvim M. J., Dickey B. F., Burns A. R., Heidelberger R., Adachi R., Munc13 proteins control regulated exocytosis in mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 345–358 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutierrez B. A., Chavez M. A., Rodarte A. I., Ramos M. A., Dominguez A., Petrova Y., Davalos A. J., Costa R. M., Elizondo R., Tuvim M. J., Dickey B. F., Burns A. R., Heidelberger R., Adachi R., Munc18-2, but not Munc18-1 or Munc18-3, controls compound and single-vesicle–regulated exocytosis in mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 7148–7159 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorentz A., Baumann A., Vitte J., Blank U., The SNARE machinery in mast cell secretion. Front. Immunol. 3, 143 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sander L. E., Frank S. P. C., Bolat S., Blank U., Galli T., Bigalke H., Bischoff S. C., Lorentz A., Vesicle associated membrane protein (VAMP)-7 and VAMP-8, but not VAMP-2 or VAMP-3, are required for activation-induced degranulation of mature human mast cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 855–863 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin-Verdeaux S., Pombo I., Iannascoli B., Roa M., Varin-Blank N., Rivera J., Blank U., Evidence of a role for Munc 18-2 and microtubules in mast cell granule exocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 116, 325–334 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bin N.-R., Jung C. H., Piggott C., Sugita S., Crucial role of the hydrophobic pocket region of Munc18 protein in mast cell degranulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 4610–4615 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woska J. R. Jr., Gillespie M. E., SNARE complex-mediated degranulation in mast cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 16, 649–656 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kittel R. J., Wichmann C., Rasse T. M., Fouquet W., Schmidt M., Schmid A., Schmid A., Wagh D. A., Pawlu C., Kellner R. R., Willig K. I., Hell S. W., Buchner E., Heckmann M., Sigrist S. J., Bruchpilot promotes active zone assembly, Ca2+ channel clustering, and vesicle release. Science 312, 1051–1054 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagh D. A., Rasse T. M., Asan E., Hofbauer A., Schwenkert I., Dürrbeck H., Buchner S., Dabauvalle M.-C., Schmidt M., Qin G., Wichmann C., Kittel R., Sigrist S. J., Buchner E., Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in Drosophila. Neuron 49, 833–844 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y., Liu X., Biederer T., Südhof T. C., A family of RIM-binding proteins regulated by alternative splicing: Implications for the genesis of synaptic active zones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 14464–14469 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suresh B., Lee J., Kim K.-S., Ramakrishna S., The importance of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in cellular reprogramming. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 6705927 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang L., Chang J., Varghese D., Dellinger M., Kumar S., Best A. M., Ruiz J., Bruick R., Peña-Llopis S., Xu J., Babinski D. J., Frantz D. E., Brekken R. A., Quinn A. M., Simeonov A., Easmon J., Martinez E. D., A small molecule modulates Jumonji histone demethylase activity and selectively inhibits cancer growth. Nat. Commun. 4, 2035 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan M., Yang X., Wang H., Shao Q., The critical role of histone lysine demethylase KDM2B in cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 10, 2222–2233 (2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crivellato E., Nico B., Gallo V. P., Ribatti D., Cell secretion mediated by granule-associated vesicle transport: A glimpse at evolution. Anat. Rec. 293, 1115–1124 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bombardier J. P., Munson M., Three steps forward, two steps back: Mechanistic insights into the assembly and disassembly of the SNARE complex. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 29, 66–71 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheu L., Pasyk E. A., Ji J., Huang X., Gao X., Varoqueaux F., Brose N., Gaisano H. Y., Regulation of insulin exocytosis by Munc13-1. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27556–27563 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ovary Z., Passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in the mouse. J. Immunol. 81, 355–357 (1958). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiang Z., Möller C., Nilsson G., Readministration of IgE is required for repeated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in mice. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 141, 168–171 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.