Abstract

The current COVID-19 pandemic is the most severe pandemic of the 21st century, on track to having a rising death toll. Beyond causing respiratory distress, COVID-19 may also cause mortality by way of suicide. The pathways by which emerging viral disease outbreaks (EVDOs) and suicide are related are complex and not entirely understood. We aimed to systematically review the evidence on the association between EVDOs and suicidal behaviors and/or ideation.

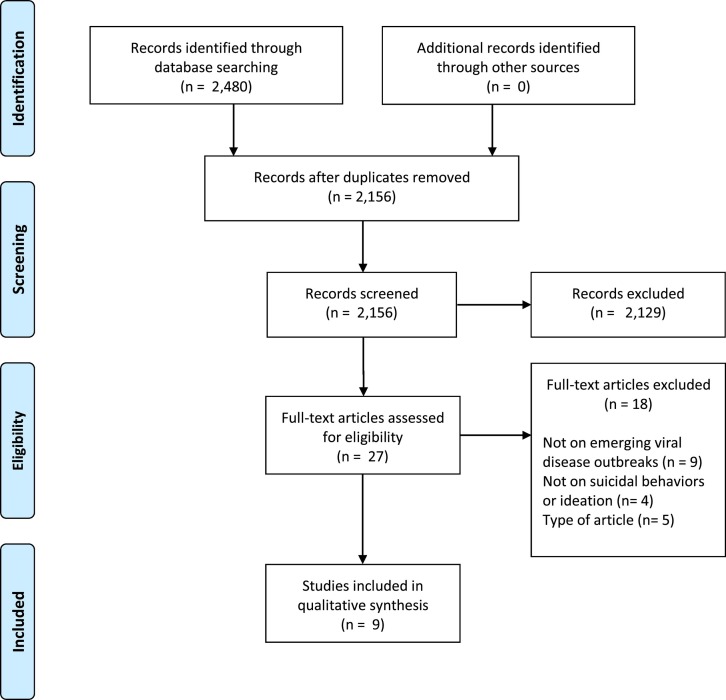

An electronic search was conducted using five databases: Medline, Embase, Web of Science, PsycINFO and Scopus in April 2020. A rapid systematic review was carried out, which involved separately and independently extracting quantitative data of selected articles.

The electronic search yielded 2480 articles, of which 9 met the inclusion criteria. Most of the data were collected in Hong Kong (n = 3) and the USA (n = 3). Four studies reported a slight but significant increase in deaths by suicide during EVDOs. The increase in deaths by suicide was mainly reported during the peak epidemic and in older adults. Psychosocial factors such as the fear of being infected by the virus or social isolation related to quarantine measures were the most prominent factors associated with deaths by suicide during EVDOs.

Overall, we found scarce and weak evidence for an increased risk of deaths by suicide during EVDOs. Our results inform the need to orient public health policies toward suicide prevention strategies targeting the psychosocial effects of EVDOs. High-quality research on suicide risk and prevention are warranted during the current pandemic.

Highlights

-

•

Few studies assessed the association between suicidal behaviors or ideation and emerging viral outbreaks.

-

•

The literature reports weak evidence for increased suicide rates during emerging viral outbreaks.

-

•

Psychosocial factors are associated with deaths by suicide during emerging viral outbreaks.

-

•

Suicide prevention strategies are needed during emerging viral outbreaks.

1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), also known as the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), first appeared in Wuhan, China, in November 2019 (Spiteri et al., 2020). Since then, COVID-19 has spread across the world, on all continents, leading The World Health Organization to officially declare the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic (Spiteri et al., 2020). Currently, there have been more than 850,000 reported deaths from COVID-19 infection and more than 25,000,000 reported cases worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is thus considered to be the most severe pandemic of the 21st century, on track to having a rising death toll.

Beyond causing respiratory symptoms and distress that lead to death, COVID-19 may also cause direct and indirect mortality by way of suicide (Chevance et al., 2020; Gunnell et al., 2020; Reger et al., 2020). On March and April 2020, the first cases of COVID-19-related suicides were reported in India and Bangladesh when two men who feared having contracted the disease took their own lives (Goyal et al., 2020; Mamun and Griffiths, 2020). Moreover, recent editorials hypothesized an increased suicide risk associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (Gunnell et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Klomek, 2017) and previous studies informed the putative association between viral infectious diseases and deaths by suicide (Catalan et al., 2011; Lund-Sørensen et al., 2016). A nationwide Danish study for example reported a significant and strong association between viral infection during hospitalization and deaths by suicide, with the number of days treated for infection being associated with elevated risk for suicide in a dose-response fashion (Lund-Sørensen et al., 2016). However, the pathways by which emerging viral disease outbreaks (EVDOs) and suicide may be related are complex and not entirely understood.

First, EVDOs are associated with psychosocial and emotional aspects (e.g., fear of infection, stigma of being diagnosed with infection, cancellation of “non-emergency” hospitalizations) that may drive risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Reger et al., 2020). The social distancing and quarantine measures that have been enacted to curb the spread of the disease have resulted in increased loneliness, anxiety, stress, and depression in the general population (Rajkumar, 2020; Wang et al., 2020). EVDOs also result in economic downturns, causing unemployment and general instability that has been associated with numerous health problems, including increased deaths by suicide (Oyesanya et al., 2015). Second, viruses exhibit neurotrophic properties and can cause severe neurological damage and nervous diseases (e.g., toxic infectious encephalopathy) that cause mental disorders (Toovey, 2008; Wu et al., 2020). In some cases, viral infections can cause disorientation, dysphoria, confusion, and delirium, which in turn lead to suicidal ideation and behaviors (Chevance et al., 2020; Reger et al., 2020; Severance et al., 2011).

These factors taken together likely increase risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors during EVDOs; however, to our knowledge, there has been no review of literature published on the topic thus far. In the current context, it is imperative to systematically review past research in order to prevent the negative impacts of the emerging pandemic and do as much as possible to reduce all deaths that are linked to the outbreak, including death by suicide. A rapid systematic review on the topic is thus urgently needed, to immediately inform prevention strategies during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of our study was to systematically review the evidence on the association between EVDOs and suicidal ideation and behaviors.

2. Methods

2.1. Systematic research

The review protocol was based on the PRISMA guideline for systematic reviews (Liberati et al., 2009) and previous rapid reviews (Tricco et al., 2015). The search was conducted between April 7th and April 11th 2020, on the five following databases: Medline, Embase, Web of Science, PsycINFO and Scopus, using the following search terms, grouped into three categories as follows:

(a) (suicid* OR self-harm OR self-injury OR self-destruct* OR DSH OR self-poison* OR self-mutilat* OR self-inflict*),

b) (pandemic* OR epidemic* OR outbreak), and.

c) (coronavirus OR influenza OR infectious OR infection OR virus OR viral OR MERS-CoV OR SARS OR Ebola OR Zika OR Chikungunya OR H1N1 OR H5N1 OR lockdown OR quarantine).

To ensure the exhaustivity of the search and the relevance of the algorithm, a pilot electronic search was performed between April 3rd and April 6th, 2020. The results of the pilot search were reviewed and the search terms and algorithm were further refined. Moreover, the electronic search was supplemented with a manual search using the reference lists of relevant publications. Corresponding authors of articles were contacted if necessary.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were (a) articles published in peer-review journals in the English, French or German language; (b) articles published since inception until April 7th, 2020; (c) articles assessing the prevalence or incidence of suicidal ideation and/or suicide attempts and/or deaths by suicide; (d) articles assessing these outcomes during or in the aftermath of an EVDO. No geographic or age restrictions were applied for the electronic research. Regarding the methodology of articles, editorials, correspondences, systematic reviews and single case reports were excluded.

Based on the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA) (Posner et al., 2007; Turecki and Brent, 2016), we differentiated suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors, which were defined as a) suicide attempts and b) deaths by suicide.

2.3. Selection process

Two authors (EL and MS) performed the electronic search on April 7th, 2020. The studies identified through the databases were then subjected to three selection filters between April 8th and 11th, depending on the titles, abstracts, and a comprehensive full-text reading of each selected paper thereafter. At each stage, the two authors independently screened all the selected articles, and identified those for which available data (title for the first stage, abstract for the second and then full-text) were consistent with the inclusion criteria of the review. After each stage, the two authors discussed their selections and agreed upon the articles to retain. When discrepancies arose, the choice to include or exclude an article was discussed with other co-authors (JB and HO).

2.4. Quality of reporting evaluation

Two authors (EL and MS) assessed the quality of included studies according to the STROBE statement (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)(von Elm et al., 2007). The level of quality was as follows: very good quality (26–32); good quality (20–26); average quality (14–20); and poor quality (<14).

2.5. Data analysis

A systematic review was carried out, which involved separately and independently extracting quantitative data by the two first authors (EL and MS) for each of the outcomes. We extracted from each article the name of the first author, the year of publication, the design of the study, the country of the study, the sample and characteristics of participants and the main results reported by the authors regarding the association between EVDOs and suicidal ideation and behaviors (e.g., prevalence or incidence during the epidemic or post-epidemic periods, risk factors, at-risk populations). The extracted data were then grouped and the evidence was summarized for each outcome. All discrepancies were discussed, and consensus was reached across all authors on the final summary. No meta-analysis was planned as the number of included studies was expected to be low and their outcomes heterogeneous.

3. Results

The electronic search yielded a total of 2480 articles. After removal of duplicates and the application of selection filters, 9 articles (Wasserman, 1992; Smith, 1995; Huang et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010; Okusaga et al., 2011; Keita et al., 2017; Harrington et al., 2018) met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart diagram according to the PRISMA guideline.

3.1. Characteristics of included articles

Most of the data were collected in Hong Kong (n = 3)(Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010) and the USA (n = 3)(Wasserman, 1992; Okusaga et al., 2011; Harrington et al., 2018). All studies were observational, with samples ranging from 66 to 87,486,713. Publication dates ranged from 1992 to 2019. Four of the articles dealt with the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (2003 SARS)(Huang et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010) outbreak, four with influenza outbreaks (Wasserman, 1992; Smith, 1995; Okusaga et al., 2011; Harrington et al., 2018) and one with the 2013–2016 Ebola virus disease in Guinea (Keita et al., 2017). The studies assessed the prevalence of deaths by suicide (n = 5)(Wasserman, 1992; Smith, 1995; Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010) or suicide attempts (n = 4)(Huang et al., 2005; Okusaga et al., 2011; Keita et al., 2017; Harrington et al., 2018). Of them, 5 studies retrospectively assessed the prevalence of deaths by suicide (Wasserman, 1992; Smith, 1995; Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008) or suicide attempts (Huang et al., 2005) during and/or after EVDOs (Okusaga et al., 2011; Harrington et al., 2018). Yip et al. (2010) retrospectively examined the characteristics of SARS-related suicides versus non-SARS-related deaths by suicide that occurred in 2003 in Hong Kong. Only one study longitudinally assessed the presence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a post-epidemic period (Keita et al., 2017). The characteristics of the included studies are displayed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Characteristics, designs and results of the studies included in the systematic review.

| Author (year) | Country | Outbreak | Study design | Population | Sample (n) | Outcome | Main results | Quality⁎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wasserman (1992) | USA | 1918 influenza | Cross-sectional Naturalistic observational study Estimate of suicide rates using the US Bureau of the census and the death registration area data |

Population of the USA | 87,486,713 | Prevalence of deaths by suicide |

|

22 |

| Smith (1995) | UK, Ireland, France | 1889–1893 “Russian” influenza | Cross-sectional Data aggregation cited in papers from others authors |

Population of the UK, Ireland and France | NA | Prevalence of deaths by suicide |

|

9 |

| Huang et al. (2005) | Taïwan | 2003 SARS | Cross-sectional Retrospective chart review of medical records (demographic and clinical characteristics) of emergency department patients, before, during and after the SARS epidemic, in a SARS-dedicated hospital |

Visitors aged over 14 of the emergency Department of the Taipei Veterans General Hospital | 17,586 | Prevalence of SA by drug overdose |

|

22 |

| Chan et al. (2006) | Hong Kong (China) | 2003 SARS | Cross-sectional Naturalistic observational study Comparison of suicide rates between 2003 and the 17 years preceding the SARS epidemic Data comes from the census and statistics Department of the Hong Kong Government |

Population of Hong Kong | NA | Prevalence of deaths by suicide |

|

21 |

| Cheung et al. (2008) | Hong Kong (China) | 2003 SARS | Cross-sectional Naturalistic observational study Comparison of suicide rates between 2003, the 10 years preceding the SARS epidemic and the year just after the SARS epidemic Comparison of socio-demographic, medical and psycho-social data of the people aged over 65 who committed suicide in 2003 in Hong Kong Data based on Coroner's death records |

Population of Hong Kong aged over 65 and people aged over 65 who died by suicide in 2003 in Hong Kong | 321 | Prevalence of deaths by suicide |

|

21 |

| Yip et al. (2010) | Hong Kong (China) |

2003 SARS | Case-control Retrospective chart review of the characteristics attributed to SARS-related suicide deaths, based on the Coroner's court reports |

People aged over 65 who died by suicide in 2003 in Hong Kong | 66 (22 cases – 44 controls) |

Characteristics of SARS-related versus non-SARS-related deaths by suicide |

|

24 |

| Okusaga et al. (2011) | USA | Influenza and coronavirus epidemics | Case-control Examination of influenza A, influenza B or coronavirus seropositivity, in adults with histories of mood disorders, suicidal attempts or healthy adults Participants were recruited into two primary studies about mood disorders and suicidal behavior |

Cases: Adults with exacerbation of mood disorders and SA - controls: Healthy adults | 257 (218 cases - 39 controls) |

Prevalence of seropositivity for viruses in people who attempted suicide |

|

22 |

| Keita et al. (2017) | Guinea | 2013–2016 Ebola virus disease | Cohort Examination of depressive symptoms among survivors of Ebola virus disease Psychological status was investigated through the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale and clinical observations |

People aged over 20 discharged from Ebola treatment centers | 256 | Incidence of SA and suicidal ideation |

|

22 |

| Harrington et al. (2018) | USA | 2009–2013 influenza epidemics | Case-controlRetrospective examination of exposure to oseltamivir or exposure to influenza only in people under 18 with SA Data come from an administrative claims database consisting of 50 million beneficiaries |

Cases: Individuals under 18 who attempted suicide and were infected by influenza virus – Controls: Healthy individuals under 18 | 251 (17 cases – 156 controls) | Prevalence of influenza diagnosis in people who attempted suicide |

|

21 |

UK = United Kingdom; 2003 SARS = 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; SA = suicide attempt.

The quality of studies was assessed with the 32-item STROBE statement, a score of 1 (presence) or 0 (absence) was coded for each item (total score on 32).

3.2. Change in rates of deaths by suicide (n = 4)

The four studies (Wasserman, 1992; Smith, 1995; Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008) reported an increase in deaths by suicide during three different EVDOs (Table 1). Two studies (Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008) reported a slight but significant increase in suicide rates in older adults in Hong Kong during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Wasserman (1992) and Smith (1995) reported increased suicide rates in the general population during two influenza outbreaks, respectively in the USA during the 1918 influenza outbreak and in Europe (United Kingdom, Ireland and France) during the 1889–1894 Russian influenza outbreak.

3.3. Change in rates of suicide attempts (n = 1)

Huang et al. (2005) reported a non-significant increase in emergency department visits for suicide attempts (drug overdoses) during the peak of the 2003 SARS epidemic in Taiwan.

3.4. Time of the outbreak

3.4.1. Epidemic peak (n = 4)

The increase in suicidal behaviors was mainly reported during the peak of the epidemic (Wasserman, 1992; Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008). Chan et al., 2006 and Cheung et al., 2008 found an excess in older adults' suicide rates at time of the epidemic peak of the 2003 SARS outbreak. Wasserman (1992) reported a peak in deaths by suicide in the US general population during the Great Influenza Epidemic occurring at the end of the peak of the flu epidemic in 1919. Huang et al. (2005) reported a non-significant increase in emergency department visits for suicide attempts (drug overdoses) during the peak of the 2003 SARS epidemic in Taiwan.

3.4.2. Late and post-epidemic periods (n = 3)

Cheung et al. (2008) reported the maintenance of higher suicide rates in older adults in the year after the 2003 SARS outbreak. Similarly, Keita et al. (2017) reported the persistence of occurrence of suicide attempts five, eleven, and twelve months after discharge from Ebola Treatment Centers. On the other hand, Huang et al. (2005) found no increase in emergency department visits due to suicide attempts in the late- and post-epidemic period of the 2003 SARS outbreak.

3.5. Sociodemographic characteristics

3.5.1. Age of participants (n = 2)

In the study by Chan et al. (2006), the increase in the rates of suicide was significant for older adults (>65) but not for people under 65 in Hong Kong. One study (Harrington et al., 2018) assessed the association between influenza infection and suicide attempt in people under 18 and found no significant association.

3.5.2. Gender of participants (n = 2)

Chan et al. (2006) found the excess mortality by suicide to be significant for older females but not for older males during the peak of the 2003 SARS outbreak, while Cheung et al. (2008) did not find any gender differences in the same context.

3.5.3. Other characteristics (n = 1)

Yip et al. (2010) found no significant differences in marital (married, single, divorced, widow or lived alone) or in socioeconomic status (employed, unemployed, retired, homemaker or received CSSA) between SARS-related and non-SARS-related suicides.

3.5.4. Factors associated with suicidal behaviors during emerging viral disease outbreaks (n = 4)

Yip et al. (2010) and Cheung et al. (2008) identified four putative factors associated with SARS-related deaths by suicide: the fear of the infection, the experience of social isolation, the disruption of normal social life and the burden among those with long-term illnesses. The fear of contracting SARS was found to be the most significant risk factor by Yip et al. (2010) and Cheung et al. (2008). Regarding the fear of being infected, unusual concerns about hygiene and reluctance to receive medical care were identified as two factors implicated in death by suicide (Yip et al., 2010). Yip et al. (2010) also reported the role of social disconnection as a risk factor for SARS-related suicides in older adults. Cheung et al. (2008) also identified high severity of chronic physical illness and high dependence as risk factors for suicide in older adults during the 2003 SARS outbreak. On the contrary, Yip et al. (2010) found no significant correlation between the level of dependence, the severity of illness, and SARS-related suicides in older adults.

Regarding psychiatric profiles, Cheung et al. and Yip et al. (2010) found no significant association between previous psychiatric disorders and deaths by suicide in older adults during the SARS 2003 outbreaks. In their case-series analysis, Keita et al. (2017) reported suicidal ideation and attempts associated with post-Ebola depressive disorders.

Regarding antiviral treatments, Harrington et al. (2018) found no significant association between oseltamivir consumption and suicide attempts in people under 18.

3.6. Type of virus

3.6.1. Coronaviruses (n = 2)

Two studies (Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008) reported an increase of suicide rates during the 2003 SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, while Okusaga et al. (2011) found no significant association between coronavirus seropositivity and suicide attempts in the USA.

3.6.2. Influenza viruses (n = 4)

Okusaga et al. (2011) reported a significant and positive association between seropositivity for influenza B and suicide attempt but not for influenza A seropositivity in depressed individuals. Harrington et al. (2018) found no significant association between influenza infection and suicide attempts in people under 18. Wasserman (1992) and Smith (1995) reported increased suicide rates during two influenza pandemics.

3.6.3. Ebola virus (n = 1)

Keita et al. (2017) reported in a case-series analysis of 256 survivors of the Ebola virus disease four cases of people experiencing suicidal ideation (n = 1) or having attempted suicide (n = 3) after their discharge from Ebola Treatment Centers.

3.7. Quality or reporting

The mean score at the STROBE checklist was 20.44 (SD = 4.14). Of the included studies, 8 were rated as good quality (Wasserman, 1992; Huang et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010; Okusaga et al., 2011; Keita et al., 2017; Harrington et al., 2018). The article by Smith (1995) was considered as poor quality as the methodological characteristics of the study (e.g., population, outcome measures, statistical analyses) were not accurately reported.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of findings

We performed the first systematic review on the impact of EVDOs on suicidal ideation and behaviors before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. First, we found the literature on the topic to be scarce but we found some weak evidence to suggest a significant increase in deaths by suicide during EVDOs. Second, older adults were reported to be particularly vulnerable to death by suicide during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Third, psychosocial factors such as the fear of being infected by the virus or social isolation related to quarantine measures were the most prominent factors associated with death by suicide during EVDOs. Fourth, on the contrary, we found only weak evidence to support the hypothesis that the neuropsychiatric symptoms induced by infection may explain the increased rates of suicidal behaviors during EVDOs.

We found scarce and weak evidence that suicidal behaviors increase during EVDOs (Wasserman, 1992; Smith, 1995; Huang et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010; Keita et al., 2017). However, there has been few studies conducted on the topic, especially regarding suicide attempts. Moreover, the strength of the association is relatively low. Indeed, several included studies reported non-significant results (e.g., Huang et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2006; Harrington et al., 2018), and the studies that reported positive results showed relatively small effects. For instance, the estimate IRRs reported by Cheung et al. (2008) and Chan et al. (2006) among older adults ranged from 1.18 to 1.32, which may fall short of being clinically meaningful. However, the findings were consistent across studies and suicide prevention strategies are thus warranted during EVDOs.

4.2. Potential pathways

Psychosocial effects of EVDOs may be regarded as the main risk factors for an increase in suicidal behaviors according to our results. The fear of being infected by the virus was indeed reported in our review to be the most salient reason for suicide attempt during EVDOs (Goyal et al., 2020; Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010), especially among older adults (Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010). This result is consistent with previous studies on emerging infectious diseases, such as HIV (Vuorio et al., 1990; Aro et al., 1994, Aro et al., 1995; Kausch, 2004) or syphilis (Savage, 2014) for which the fear of being infected was also found to be correlated with suicide ideation or attempts. Recently, deaths by suicide associated with the fear of being infected with the virus were reported during the current COVID-19 pandemic (Goyal et al., 2020; Mamun and Griffiths, 2020).

Social isolation was also found in our review to be a significant risk factors for deaths by suicide during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Although none of the included articles directly assessed the impact of lockdown measures on suicidal behaviors, social isolation and loneliness may foster suicidal ideation and attempts in the general population (Calati et al., 2019; Brooks et al., 2020). In a recent narrative review of 40 articles, Calati et al. (2019) reported that objective social isolation and subjective feelings of loneliness are associated with higher suicidal ideation and behaviors. In the same vein, Brooks et al. (2020) reported that quarantine and lockdown measures are associated with poorer mental health status in the general population. However, the effects of social isolation observed in previous EVDOs may be different than the effects of the current pandemic. Indeed, technologies, such as videoconferencing, are now more widely available. Moreover, the quarantine measures are applied to the whole population during the COVID-19 pandemic, while they were only applied to vulnerable groups (e.g., older adults, people with poor health conditions) during the 2003 SARS epidemic (Cheung et al., 2008), which may have been stigmatizing and isolating for those who were forced into quarantine.

Unexpectedly, we found no evidence for an increased risk of deaths by suicide in people with previous psychiatric disorders during EVDOs (Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010). However, this result has to be interpreted with caution as only three studies (Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010; Keita et al., 2017) evaluated the effect of previous psychiatric disorders. People with mental disorders are indeed considered as a vulnerable population during the COVID-19 pandemic (Chevance et al., 2020; Reger et al., 2020), and may still require preventive interventions during lockdown (Chevance et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2020).

4.3. Implications for suicide prevention strategies during EVDOs

Our results indicate the need to design adaptive suicide prevention during EVDOs, focusing on their psychosocial impacts. First, our results may give the impression that practitioners should routinely assess for fear of infection during EVDOs to detect people with higher suicide risk. For example, Ahorsu et al. (2020) recently developed and validated the 7-item Fear of COVID-19 Scale in a sample of 717 Iranian participants. However, there is insufficient evidence to support the clinical utility of such screenings to reduce mental health symptoms (Gilbody et al., 2006; Gilbody et al., 2008; Keshavarz et al., 2013) or prevent suicides (Oyama et al., 2006; Belsher et al., 2019). Thus, it would be premature to integrate these screenings into clinical practice at this point. Second, as emphasized by Reger et al. (2020), social connection plays a key role in suicide prevention, so that the prevention of loneliness induced by quarantine measures should be included in public health policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, brief contact interventions, through phone calls or postcards, appear to be a promising strategy to reduce suicide risk by providing social support and promoting distance-based access to mental health care (Milner et al., 2016). Third, during the 2003 SARS outbreak, older adults were reported as being particularly vulnerable to suicide (Chan et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2010). Thus, mitigating the impact of social isolation and of the fear of infection in older adults are two specific objectives that must be properly addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, two recent systematic reviews reported that the literature on suicide prevention in older adults (Zeppegno et al., 2019) and in nursing homes (Chauliac et al., 2019) is scarce. Psychotherapies for suicide prevention have been tailored for older adults and have been demonstrated to be effective in reducing suicidal behaviors (Zeppegno et al., 2019). Interestingly, telephone helplines providing brief counselling and emotional support have been reported to be effective in preventing suicidal behaviors in older adults in Italy (De Leo et al., 1995, De Leo et al., 2002) and in Hong Kong (Chan et al., 2018). Fourth, regarding the results from Cheung et al. (2008) and Keita et al. (2017) on suicidal behaviors in the post-epidemic periods, prevention strategies must be designed in a long-term fashion and also target people infected by the SARS-CoV-2 as they may exhibit high level of post-traumatic, anxiety and depressive symptoms in the aftermath of the infection (Duan and Zhu, 2020).

4.4. Limitations

Our review has several limitations. First, the number of included articles is low and their quality is heterogeneous. This highlights the scarcity of literature on the topic and the urgent need to collect nationwide and worldwide data on the psychological impact of the current COVID-19 pandemic. In agreement with recent editorials (Gunnell et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2020), our results stress the need to perform high quality research on suicide risk and prevention in the current pandemic context. Second, the included studies were performed in a small number of countries. Suicidal behaviors are known to be shaped by cultural and social contexts, so the generalizability of our conclusions may be hampered. For example, the suicide rate in older adults in Hong Kong was known to be high compared to other countries at the period preceding the 2003 SARS outbreak (Chi et al., 1998). Third, only two studies assessed the long term impact of EVDOs on suicidal ideation and behaviors, so that the evidence on the long-term impact of EVDOs remains poorly understood. Thus, our results only weakly inform what the long-term impact of the current COVID-19 pandemic might be on suicidal behaviors. Fourth, the review did not examine other specific high-risk groups than older adults, so that our results fail to inform targeted suicide prevention strategies. Finally, the between-studies heterogeneity was high regarding quality, design, population, and outcomes and may thus limit the relevance of our results.

5. Conclusion

While the literature on the impact of EVDOs on suicidal ideation and behaviors was found to be scarce, the existing literature shows weak evidence for an increased risk of deaths by suicide during viral outbreaks, especially during the peak epidemics. The pathways by which EVDOs and suicide are related remain not entirely understood, but their psychosocial effects may be regarded as the main risk factors. Public health and suicide prevention strategies must target the most vulnerable populations that struggle the most to adapt to EVDOs.

Footnotes

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Ahorsu D.K., Lin C.Y., Imani V., Saffari M., Griffiths M.D., Pakpour A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict, published online March. 2020;27:2020. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro A.R., Jallinoja P.T., Henriksson M.M., Lönnqvist J.K. Fear of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and fear of other illness in suicide. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1994;90:65–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro A.R., Henriksson M., Leinikki P., Lönnqvist J. Fear of AIDS and suicide in Finland: a review. AIDS Care. 1995;7:5187–5197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsher B.E., Smolenski D.J., Pruitt L.D., Bush N.E., Beech E.H., Workman D.E., Morgan R.L., Evatt D.P., Tucker J., Skopp N.A. Prediction models for suicide attempts and deaths: a systematic review and simulation. JAMA Psych. 2019;76:642–651. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calati R., Ferrari C., Brittner M., Oasi O., Olié E., Carvalho A.F., Courtet P. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: a narrative review of the literature. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;245:653–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan J., Harding R., Sibley E., Clucas C., Croome N., Sherrn L. HIV infection and mental health: suicidal behaviour--systematic review. Psychol Health Med. 2011;16:588–611. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.582125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S.M., Chiu F.K., Lam C.W., Leung P.Y., Conwell Y. Elderly suicide and the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:113–118. doi: 10.1002/gps.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C.H., Wong H.K., Yip P.S. Exploring the use of telephone helpline pertaining to older adult suicide prevention: a Hong Kong experience. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;236:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauliac N., Leaune E., Gardette V., Poulet E., Duclos A. Suicide prevention interventions for older people in nursing homes and long-term care facilities: a systematic review. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2019;891988719892343 doi: 10.1177/0891988719892343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung Y.T., Chau P.H., Yip P.S. A revisit on older adults suicides and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:1231–1238. doi: 10.1002/gps.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevance A., Gourion D., Hoertel N., Llorca P.-M., Thomas P., Bocher R., Moro M.-R., Laprevote V., Benyamina A., Fossati P., Masson M., Leaune E., Leboyer M., Gaillard R. 2020. Ensuring mental health care during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in France: a narrative review. Encephale, published online March 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi I., Yip P.S., Yu G.K., Halliday P. A study of elderly suicides in Hong Kong. Crisis. 1998;19:35–46. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.19.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D., Carollo G., Dello Buono M. Lower suicide rates associated with a Tele-help/Tele-check service for the elderly at home. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152:632–634. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D., Dello Buono M., Dwyer J. Suicide among the elderly: the long-term impact of a telephone support and assessment intervention in northern Italy. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2002;181:226–229. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L., Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:300–302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S., Sheldon T., Wessely S. Should we screen for depression? BMJ. 2006;332:1027–1030. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7548.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S., Sheldon T., House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2008;178:997–1003. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal K., Chauhan P., Chhikara K., Gupta P., Singh M.P. Fear of COVID 2019: first suicidal case in India ! Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;49:101989. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D., Appleby L., Arensman E., Hawton K., John A., Kapur N., Khan M., O’Connor R.C., Pirkis J., COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:468–471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington R., Adimadhyam S., Lee T.A., Schumock G.T., Antoon J.W. The relationship between oseltamivir and suicide in pediatric patients. Ann. Fam. Med. 2018;16:145–148. doi: 10.1370/afm.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., Ballard C., Christensen H., Cohen Silver R., Everall I., Ford T., John A., Kabir T., King K., Madan I., Michie S., Przybylski A.K., Shafran R., Sweeney A., Worthman C.M., Yardley L., Cowan K., Cope C., Hotopf M., Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.C., Yen D.H., Huang H.H., Kao W.F., Wang L.M., Huang C.I., Lee C.H. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreaks on the use of emergency department medical resources. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68:254–259. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70146-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausch O. Irrational fear of AIDS associated with suicidal behavior. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2004;10:266–271. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keita M.M., Taverne B., Sy Savané S., March L., Doukoure M., Sow M.S., Touré A., Etard J.F., Barry M., Delaporte E., PostEboGui Study Group Depressive symptoms among survivors of Ebola virus disease in Conakry (Guinea): preliminary results of the PostEboGui cohort. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:127. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz H., Fitzpatrick-Lewis D., Streiner D.L., Maureen R., Ali U., Shannon H.S., Raina P. Screening for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open. 2013;1:E159–E167. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20130030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomek A.B. Suicide prevention during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;7:390. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30142-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund-Sørensen H., Benros M.E., Madsen T., Sørensen H.J., Eaton W.W., Postolache T.T., Nordentoft M., Erlangsen A. A nationwide cohort study of the association between hospitalization with infection and risk of death by suicide. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;2016(73):912–919. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun M.A., Griffiths M.D. First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51:102073. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner A., Spittal M.J., Kapur N., Witt K., Pirkis J., Carter G. Mechanisms of brief contact interventions in clinical populations: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:194. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0896-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okusaga O., Yolken R.H., Langenberg P., Lapidus M., Arling T.A., Dickerson F.B., Scrandis D.A., Severance E., Cabassa J.A., Balis T., Postolache T.T. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;130:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama H., Goto M., Fujita M., Shibuya H., Sakashita T. Preventing elderly suicide through primary care by community-based screening for depression in rural Japan. Crisis. 2006;27:58–65. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.27.2.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyesanya M., Lopez-Morinigo J., Dutta R. Systematic review of suicide in economic recession. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5:243–254. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K., Oquendo M.A., Gould M., Stanley B., Davies M. Columbia classification algorithm of suicide assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1035–1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger M.A., Stanley I.H., Joiner T.E. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019 - A perfect storm? JAMA Psych. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060. published online April 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage G.H. Fear of syphilis and suicide. 1914. Practitioner. 2014;258:37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severance E.G., Dickerson F.B., Viscidi R.P., Bossis I., Stallings C.R., Origoni A.E., Sullens A., Yolken R.H. Coronavirus immunoreactivity in individuals with a recent onset of psychotic symptoms. Schizophr. Bull. 2011;37:101–107. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith F.B. The Russian Influenza in the United Kingdom, 1889-1894. Soc History Med. 1995;8:55–73. doi: 10.1093/shm/8.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiteri G., Fielding J., Diercke M., Campese C., Enouf V., Gaymard A., Bella A., Sognamiglio P., Sierra Moros M.J., Riutort A.N., Demina Y.V., Mahieu R., Broas M., Bengnér M., Buda S., Schilling J., Filleul L., Lepoutre A., Saura C., Mailles A., Levy-Bruhl D., Coignard B., Bernard-Stoecklin S., Behillil S., van der Werf S., Valette M., Lina B., Riccardo F., Nicastri E., Casas I., Larrauri A., Salom Castell M., Pozo F., Maksyutov R.A., Martin C., Van Ranst M., Bossuyt N., Siira L., Sane J., Tegmark-Wisell K., Palmérus M., Broberg E.K., Beauté J., Jorgensen P., Bundle N., Pereyaslov D., Adlhoch C., Pukkila J., Pebody R., Olsen S., Ciancio B.C. First cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the WHO European Region, 24 January to 21 February 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020:25(9). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toovey S. Influenza-associated central nervous system dysfunction: a literature review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2008;6:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A.C., Antony J., Zarin W., Strifler L., Ghassemi M., Ivory J., Perrier L., Hutton B., Moher D., Straus S.E. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13:224. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turecki G., Brent D.A. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet. 2016;387:1227–1239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P., STROBE Initiative The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuorio K.A., Aärelä E., Lehtinen V. Eight cases of patients with unfounded fear of AIDS. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 1990;20:405–411. doi: 10.2190/GVPC-EXK6-LF35-PBCJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. 17. pii: E1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman I.M. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910-1920. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22:240–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019): weekly epidemiological update. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Accessed September 4, 2020.

- Wu Y., Xu X., Chen Z., Duan J., Hashimoto K., Yang L., Liu C., Yang C. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. published online March 30. pii: S0889–1591(20)30357–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H., Chen J.H., Xu Y.F. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip P.S., Cheung Y.T., Chau P.H., Law Y.W. The impact of epidemic outbreak: the case of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis. 2010;31:86–92. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeppegno P., Gattoni E., Mastrangelo M., Gramaglia C., Sarchiapone M. Psychosocial suicide prevention interventions in the elderly: a mini-review of the literature. Front. Psychol. 2019;9:2713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]