Abstract

Background

American Indians (AIs) live with historical trauma, or the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding that is passed from one generation to the next in response to the loss of lives and culture. Psychological consequences of historical trauma may contribute to health disparities.

Purpose

Here, we investigate whether historical trauma predicts changes in psychological stress associated with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in AI adults. Based on the stress-sensitization theory, we hypothesize that greater historical trauma will predict greater increases in levels of psychological stress from before the onset of the pandemic to after. Method: Our analytic sample consisted of 205 AI adults. We measured historical trauma and levels of psychological stress before and after the onset of the pandemic.

Results

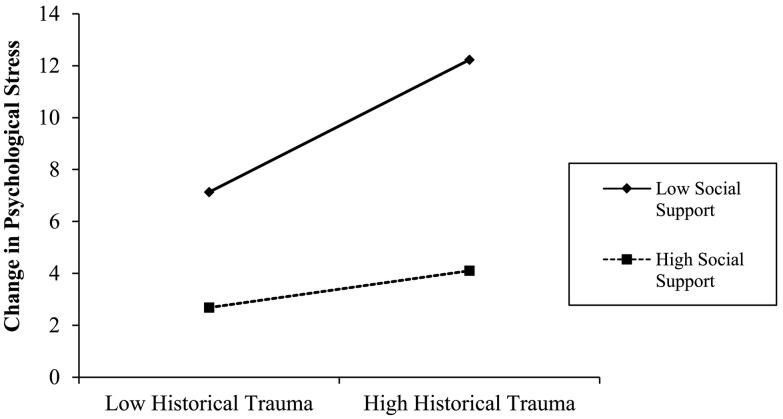

Using hierarchical regression models controlling for age, biological sex, income, symptoms of depression and anxiety, psychological stress at Time 1, COVID-19 specific stress, and childhood trauma, we found that greater historical trauma preceding the pandemic predicted greater increases in psychological stress (β = 0.38, t = 5.17 p < .01, ΔR2 = 0.12), and levels of social support interacted with historical trauma to predict changes in psychological stress (β = −0.19, t = −3.34, p = .001, ΔR2 = 0.04). The relationship between historical trauma and changes in stress was significant for individuals with low levels of social support.

Conclusions

Historical trauma may contribute to AI mental health disparities, through heightened psychological stress responses to life stressors and social support appears to moderate this relationship.

Keywords: American Indians, COVID-19 pandemic, Historical trauma, Psychological stress, Social support

Highlights

-

•

In American Indians, historical loss predicts stress responses to a life event

-

•

Relationship between historical trauma and stress is moderated by social support

-

•

Relationship is independent of demographics, early trauma, anxiety and depression

1. Introduction

In addition to high rates of psychological stress and trauma across the life-span [[1], [2], [3], [4]], American Indians (AIs) also experience historical trauma, which is defined as the emotional and psychological injury both over the life span and across generations resulting from massive group trauma for a group of people who share an identity or circumstance [[5], [6], [7]]. For over 500 years, AIs have endured various forms of genocide and colonization imposed by European and American policy. As an example, AIs were systematically and forcibly removed from their families and homes and placed in boarding schools that were designed to force assimilation and eradicate the AI way of life, traditions and culture [8]. Historical losses—the loss of language, land, culture, and loved ones—are a direct product of such policies enforced by the United States government, and prior research indicates that the experience of these losses and the frequency with which AIs think about these losses predicts physical and mental health and substance use [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. A broad constellation of responses to these multigenerational traumas has been observed and is referred to as the historical trauma response [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]].

Mounting evidence indicates that historical trauma and its psychological sequelae may contribute to enduring health disparities. As a population, AIs have disproportionately high incidence of chronic mental and physical health conditions [[15], [16], [17], [18]], and researchers have hypothesized that historical trauma may account for a significant portion of high incidence of mental health disorders [19,20]. While there is considerable research in other racial and ethnic groups indicating that patterns of responses to life stressors may contribute to health and disease risk [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]] less is known about how these responses may contribute to enduring health disparities in AIs and whether historical loss may inform the degree to which life events affect levels of psychological stress. This is important since levels of psychological stress predict subsequent depressive symptoms and risk for mental health conditions [[22], [23], [24], [25], [26]].

The stress sensitization model proposes that individuals who have higher levels of childhood adversity have a lower tolerance to stress, which increases risk of developing psychopathology when exposed to subsequent stressful events [[27], [28], [29]]. For example, previous exposure to trauma predicts higher post-disaster traumatic stress levels in children who have experienced a natural disaster [30]. Additionally, when examining those who have had similar levels of life stress over the past year, individuals exposed to greater childhood adversity report higher levels of perceived stress [31] and higher levels of childhood adversity have been associated with higher emotional responses to life events [32].

A body of research demonstrates that trauma experienced in an ancestral generation is associated with adverse health outcomes in future generations [[33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]] through its' impact on the developmental experience. Conching & Thayer (2019) [39] propose two pathways explaining how historical trauma may increase exposure to trauma during the developmental experience. One pathway focuses on biological pathways through which historical trauma may affect outcomes, positing that historical trauma exerts epigenetic effects during prenatal and postnatal periods. The second pathway involves more direct exposure to trauma at the individual level. Populations that have experienced higher levels of historical trauma are more likely to be exposed to trauma throughout the life course [[40], [41], [42], [43]]. Therefore, higher historical loss and/or trauma may increase childhood trauma during development [39]. This line of work suggests higher adversity and trauma may increase perceptions of stress to future events. However, the stress sensitization model has not been extensively explored an AIs, and it is unknown whether similar relationships would be observed for historical loss.

The stress buffering hypothesis posits that during periods of high stress, interpersonal social support enhances an individual's ability to cope and reduces responses to stress [44]. Social support has been especially effective in the context of stress or adversity [45,46]. Indeed, in AIs, evidence suggests social support can buffer the negative effects of childhood trauma [47], improve psychosocial functioning in those undergoing addiction treatment [48], increase resilience [49] and increase life satisfaction [50]. Across other racial and ethnic groups, social support is known to reduce the degree to which life events affect psychological stress [51,52]. While this relationship has not been investigated in AIs, previous research using data from interviews with older AI adults indicates that social support associates with lower levels of traumatic stress [53].

Infectious disease outbreaks are known to elicit psychological responses [54,55], including increased levels of psychological stress [56,57]. On March 11, 2020, the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was named a pandemic. Six days later, it was acknowledged as a national emergency in the United States. While individuals may experience stress directly related to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also possible that the circumstances may make individuals feel less able to manage overall and they may find their lives less controllable and feel overloaded. The present dataset includes measures of perceived psychological stress before the pandemic and during the pandemic. Based on the described bodies of work, we hypothesize that in AI adults, historical loss will inform changes in psychological stress following the onset of the pandemic, with higher frequency of thinking about historical losses predicting greater increases in levels of psychological stress. Further, we hypothesize that perceived levels of social support may moderate this relationship.

2. Methods

AI participants from a previous cross-sectional survey study provided their email addresses for participation in possible follow-up studies. These participants were drawn from a Qualtrics research panel and from previous investigations which were advertised nationally through social media sites targeting AI adults. After receiving Institutional Review Board approval, we contacted all 300 of these participants. Out of these participants, we had a sample of 210 interested AI adults. We excluded five of these participants from our analyses who did not have historical loss data, thus giving us an analytic sample of 205. All participants provided written informed consent online before beginning the surveys. Time 1 data was collected in the final week of February 2020. The second wave of data reported here was collected during the final week of April and the first week of May 2020. Participants were given $10 Amazon gift cards for their completion of each survey. To be eligible for participation, participants had to self-identify as American Indian and be over the age of 18. All surveys were administered online using the Qualtrics platform. Surveys administered at Time 1 included demographic questions, measures of psychological stress, historical loss, symptoms of depression and anxiety, sleep, emotion regulation, alcohol behaviors, measures of socioeconomic status across the life-span and, measures of early life experiences. At the second wave of data collection, participants provided the zip code of their current residence and repeated measures of psychological stress, depression and anxiety. We also administered questions about COVID-19 specific stress, social distancing behaviors, and measures of changes in behaviors in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Measures

3.1. Historical loss

We used the Historical Loss Scale (HLS) [38], a standardized measure that assesses the frequency with which Indigenous individuals think about the losses to their culture, land and people as a result of European colonization. The HLS includes 12 items. Participants are asked to indicate the frequency with which they think about the described losses. Participants provide their response using a 6-point scale, anchored by (1) several times a day and (6) never. Each response is reverse-scored and a composite score is calculated as the sum of each of these responses. Previous work indicates that the 12 items can be adequately explained by a single latent factor [38]. Cronbach's alpha for the HLS was 0.95.

3.2. Social support

We used the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 [58] to obtain a measure of the perceived availability of others to talk to about one's problems, which is measured using the appraisal subscale of the ISEL-12. The appraisal subscale is comprised of 4 items including “I feel that there is no one I can share my most private worries and fears with,” and “When I need suggestions on how to deal with a personal problem, I know someone I can turn to.” Participants used a 4-point scale to indicate the degree to which they agreed with each of the 4 statements (0 = definitely false, 1 = probably false, 2 = probably true, and 3 = definitely true). Negatively framed items were reverse scored and a total score was created by summing responses to each item. The scale was administered at Time 1, before the onset of the pandemic.

3.3. Psychological stress

We used the Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10) as a measure of general perceived psychological stress [59]. The PSS-10 is the most widely used instrument for measuring subjective psychological stress. It is a measure of the degree to which situations in an individual's life are appraised as stressful. It focuses on how unpredictable, uncontrollable and overloaded individuals find their lives. Participants respond to each of the 10 questions using a scale of 0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = fairly often, and 4 = very often. PSS-10 scores are obtained by reverse scoring responses on the 4 positively stated items and then summing across all 10 items. The scale was administered at Time 1, before the onset of pandemic, and Time 2, one month after declaration of the pandemic. Cronbach's alpha for the PSS-10 at time 1 was 0.81 and 0.79 at Time 2.

3.4. COVID-19 specific stress

As a measure of psychological stress, specific to COVID-19, participants responded to the following question at Time 2, “How stressed do you feel when you think about the Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic?” using a 7-point scale anchored with (1) not at all stressed and (7) extremely stressed. This question was given to participants at Time 2.

3.5. Symptoms of depression and anxiety

We used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) as a measure of current symptoms of depression and anxiety at Time 1 [60]. The HADS has 14 items, 7 items comprise a depression subscale, and 7 items comprise an anxiety subscale. Individuals respond to each item using a four-point response category (0–3), with possible scores ranging from 0 to 21 for depression and 0–21 for anxiety. Cronbach's alpha was 0.88 for the anxiety subscale and 0.86 for the depression subscale.

3.6. Early life trauma

As a measure of childhood adversity, we used the Risky Families Questionnaire (RFQ) [61]. The RFQ is a 13-item self-report instrument which asks participants to report how frequently certain events occurred in their homes during the ages of 5–15 years of age utilizing a 5-point Likert Scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very often). Example questions include “How often would you say there was quarreling, arguing or shouting between your parents?” and “How often did a parent or other adult in the house push, grab, shove or slap you?” This scale was administered at Time 1. The Cronbach alpha in this sample was 0.92.

3.7. Annual income

Participants reported their annual household income on a scale from 1 (below US$20,000), 2(US$20,000–$40,000), 3(US$40,001-60,000), 4(US$60,001-80,000), 5(US$80,001-100,000) and 6 (US$100,001 and above) [62,63]. This measure was administered at Time 1.

3.8. Covid-19 financial burden

We asked participants, “Has the COVID-19 pandemic been a financial burden to you and/or your family? Participants could respond, “Yes,” “No,” or “Unsure.” This measure was administered at Time 2.

4. Data analyses

Statistical Analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 24; IBM, Armonk, NY). Continuous covariates were centered with z-scores prior to being used in analyses. Participant gender was coded as 1 = female, 2 = male. Initial Pearson product-moment correlation analyses were performed to determine bivariate associations between demographic variables, symptoms of depression and anxiety, historical loss, social support, psychological stress before the pandemic and changes in psychological stress from time 1 to time 2. Next, hierarchical linear regression models were used to test our hypotheses. We first examined the relationship between historical loss and changes in psychological stress. Next, we created an interaction term and tested whether levels of social support moderated the relationship. To further probe this interaction, we used the Johnson-Neyman technique [54] to identify specific values of historical trauma for which the relationship between social support and changes in psychological stress was statistically significant.

5. Results

Our sample consisted of 205 AI adults (mean age = 53 years, SD = 13 years). 59.8% identified as female, and 40.2% identified as male. The majority of the sample did not live on a tribal reservation (91.5%). Based on collection of zip code of participant residence collected at Time 2, participants resided in 46 different states in the United States, with 11% of participants in Texas, 11% of participants in California, 7% of participants in Oklahoma, and 5% of participants in Florida. Thirty-nine percent of our sample indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had placed a financial burden on themselves or their family. Table 1 presents mean, standard deviation, and range of values for main variables of interest and Table 2 presents bivariate correlations between main variables of interest. At the time of the second wave of data collection, 5 of our participants indicated that they had been diagnosed with COVID-19.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 205).

| Observed Range | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Time 1) | 30–99 | 54.96 | 13.04 |

| Income (Time 1) | 1–6 | 2.96 | 1.72 |

| Anxiety symptoms (Time 1) | 0–21 | 6.96 | 5.22 |

| Depressive symptoms (Time 1) | 0–21 | 5.91 | 4.68 |

| Psychological Stress (Time 1) | 2–30 | 10.74 | 5.43 |

| Covid-19 specific stress (Time 2) | 1–7 | 3.31 | 1.70 |

| Social Support (Time 1) | 2–12 | 7.13 | 2.69 |

| Historical Loss (Time 1) | 12–72 | 29.09 | 16.75 |

| Psychological Stress (Time 2) | 3–39 | 16.13 | 7.50 |

| Change in Psychological Stress (From Time 1 to Time 2) | -5 to +26 | 4.83 | 6.18 |

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations between main variables of interest.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | |||||||||

| 2. Sex | 0.05 | – | ||||||||

| 3. Income | 0.06 | 0.29⁎⁎ | – | |||||||

| 4. Depressive symptoms | −0.25⁎⁎ | −0.13 | −0.24⁎⁎ | – | ||||||

| 5. Anxiety | −0.34⁎⁎ | −0.15⁎ | −0.26⁎⁎ | 0.76⁎⁎ | – | |||||

| 6. Historical Loss (Time 1) | −0.09 | −0.003 | −0.16⁎ | 0.30⁎⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | – | ||||

| 7.ISEL-appraisal (Time 1) | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.25⁎⁎ | – | |||

| 8. COVID specific stress | −0.14⁎⁎ | −0.16⁎ | −0.09 | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | −0.11 | – | ||

| 9. Psychological Stress (Time 1) |

−0.13 |

−0.09 |

−0.08 |

0.12 |

0.16⁎ |

0.32⁎⁎ |

0.04 |

0.06 |

- |

|

| 10. Change in Psychological stress (Time 2) | 0.03 | −0.003 | −0.09 | 0.24⁎⁎ | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | −0.64⁎⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | −0.02 | – |

Note: Sex is coded as Female = 1, Male = 2.

Correlation significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

Correlation significant at the 0.01 level (two tailed).

To test our first hypothesis, we used a hierarchical linear regression model predicting changes in psychological stress from before the pandemic to during the pandemic, with the covariates of age, gender, annual income, symptoms of depression and anxiety, COVID-19 specific stress, psychological stress at Time 1, and early life trauma (as measured by the RFQ) in Block 1. In Block 2, we entered scores on the historical loss scale. Preliminary analyses demonstrated that there were no violations of the assumptions of multicollinearity homoscedasticity, normality, and linearity. In line with our hypothesis, participants who reported more historical loss had greater increases in psychological stress during this time period (β = 0.38, t = 5.17 p < .001, ΔR2 = 0.12; see Table 3 ).1 To test our second hypothesis, in a separate hierarchical regression model, we entered the same covariates, and mean centered historical loss and ISEL-12 appraisal subscale scores. In Block 2, we entered the interaction term between historical loss and the appraisal subscale score. In this regression model, the interaction between historical loss and appraisal was a significant predictor of changes in psychological stress from time 1 to time 2 (β = −0.19, t = −3.34, p = .001, ΔR2 = 0.04). Table 4 presents the full results from this regression model.1 The pattern of this interaction is displayed in Fig. 1 . The Johnson-Neyman Technique revealed that the relationship between historical trauma and changes in psychological stress from before the pandemic to during the pandemic was statistically significant for individuals with scores on the ISEL-12 appraisal subscale of 9 or lower. In other words, for individuals who felt that they had people in their life to turn to for support (i.e. scores above 9 on the ISEL-12 appraisal subscale), historical loss was not a significant predictor of changes in psychological stress in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Using the Johnson-Neyman technique once again [64], we found that the relationship between social support and changes in psychological stress was statistically significant across all values of historical loss.

Table 3.

Fully adjusted hierarchical linear regression model with historical Loss predicting changes in psychological stress.

| β | p | ΔR2 | Lower CI |

Upper CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||||

| Age | 0.08 | 0.28 | −0.06 | 0.22 | |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.89 | −0.13 | 0.15 | |

| Income | −0.03 | 0.65 | −0.17 | 0.11 | |

| COVID-19 Specific Stress | 0.04 | 0.59 | −0.11 | 0.19 | |

| Perceived Stress (PSS) | −0.13 | 0.07 | −0.26 | 0.01 | |

| Anxiety (HADS) | 0.04 | 0.72 | −0.19 | 0.27 | |

| Depression (HADS) | 0.13 | 0.20 | −0.07 | 0.33 | |

| Childhood Trauma (RFQ) | −0.07 | 0.38 | −0.22 | 0.08 | |

| .08a | |||||

| Step 2 | |||||

| Historical Loss (HLS) | 0.38 | 0.000 | 0.24 | 0.52 | |

| .12b |

Note: a = ΔR2 for Step 1, b = ΔR2 for Step 2.

Table 4.

Fully adjusted hierarchical linear regression model with the interaction between historical loss and social support predicting changes in psychological stress.

| β | p | ΔR2 | Lower CI |

Upper CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | −0.02 | 0.67 | −0.13 | 0.09 | ||

| Gender | 0.00 | 0.95 | −0.10 | 0.11 | ||

| Income | −0.08 | 0.14 | −0.19 | 0.03 | ||

| COVID-19 Specific Stress | 0.05 | 0.41 | −0.07 | 0.17 | ||

| Perceived Stress (PSS) | −0.07 | 0.23 | −0.17 | 0.04 | ||

| Anxiety (HADS) | −0.01 | 0.90 | −0.19 | 0.17 | ||

| Depression (HADS) | 0.10 | 0.23 | −0.06 | 0.25 | ||

| Childhood Trauma (RFQ) | −0.10 | 0.10 | −0.22 | 0.02 | ||

| Social Support (ISEL) | −0.56 | 0.00 | −0.67 | −0.45 | ||

| Historical Loss (HLS) | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.34 | ||

| .45a | ||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Social Support (ISEL) x Historical Loss (HLS) | −0.19 | 0.02 | 0.032 | −0.21 | −0.02 | |

| .04b |

Note: a = ΔR2 for Step 1, b = ΔR2 for Step 2.

Fig. 1.

Pattern of findings from a linear regression model with historical trauma and social support predicting changes in psychological stress from time 1 to time 2. The regression model included age, sex, symptoms of depression and anxiety (Time 1), psychological stress (time 1) and childhood trauma.

6. Discussion

The findings presented here present novel and initial evidence that historical loss in AI adults may shape psychological stress responses to life stressors. Specifically, we found that AI adults who think more frequently about historical loss associated with the colonization and genocide of their people, experienced greater increases in psychological stress from before the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic to one month following the declaration of the pandemic. Interestingly, we found evidence that social support moderates the relationship between historical loss and these changes. Specifically, the relationship between historical loss and changes in psychological stress was significant for AI adults with relatively low levels of perceived social support but not for AI adults with high levels of perceived social support, indicating that social support may dampen psychological stress responses to life events for AI adults, and that the negative implications of historical trauma for psychological stress may only be present in the context of low levels of social support. It is important to note that the interaction we observed was independent of reported depression and anxiety symptoms at Time 1, independent of annual income, and independent of levels of childhood trauma, indicating that the effect of the frequency of thoughts about historical loss on psychological stress response is independent of the effects of depressive symptoms, generalized levels of anxiety, income, and exposure to trauma in childhood.

While previous work indicates that childhood trauma sensitizes individuals to future life stressors [[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]], to our knowledge our findings provide novel evidence that historical trauma may have similar implications in AI adults. Prior work suggests that historical trauma may contribute to disproportionate incidence of mental health disorders in AIs, and AI scholars and elders have indicated that historical losses and associated trauma should be addressed in order to improve AI mental health [[65], [66], [67], [68], [69]]. Our work adds to this literature by suggesting that one pathway through which historical trauma may contribute to poor mental health for AIs is by heightening psychological stress responses to life events. Our findings are also in line with a large body of work highlighting the potential for social support to dampen psychological stress responses to life stressors or events. As noted in our results section, our findings indicate that higher levels of social support are beneficial with regards to changes in psychological stress for all AI adults in our sample, regardless of the degree of reported historical trauma.

There are important limitations to note. First, while the data is prospective, the observed relationships are still correlational in nature. As such, causality cannot be inferred. Second, it is possible that participants endured other traumas or stressful events between Time 1 and Time 2 data collection which may not have been related to the COVID-19 pandemic. While we do have a measure of COVID-19 specific stress (which was also positively related to Historical loss), we were most interested in changes in individual's perceptions of how controllable and manageable they found the demands in their overall life in the context of the pandemic. Furthermore, the findings reported here included COVID-19 specific stress as a covariate.

In addition, the majority of participants in this research lived in urban settings and did not live on a tribal reservation. Due to the small number of participants who reported living on a reservation, we were unable to investigate whether place of residence (i.e. on or off a tribal reservation) would affect the pattern of our findings. It is also possible that some of the AI participants in our sample were not aware of the historical losses their people have faced. If this were the case, we believe that they would likely indicate that they never think about the losses that are described in the Historical Loss Scale. It is also possible that some of these individuals are acutely aware of the historical trauma and loss, but never think about these losses. These participants also would have indicated that they never think about the losses described in the Historical Loss Scale. Previous research suggests that American Indian adolescents and children living on tribal reservations are highly aware of the historical trauma faced by their ancestors and that this awareness remained important into late adulthood [13], and a separate investigation found that AIs living in urban setting had significantly higher scores on the historical loss scale compared to AIs living on tribal reservations [70]. Future work should explore whether the degree to which AIs are aware of these historical traumas and losses informs psychological stress responses in a similar manner. Finally, while this research focuses exclusively on the outcome of psychological stress, this is an outcome which is relevant for mental and physical health [15,[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]], and which shapes health behaviors such as substance use and sleep which are implicated in the conditions which disproportionately affect AIs [[71], [72], [73]].

Future work is needed to better understand how historical loss shapes trajectories of psychological stress over time in response to life stressors, and whether historical loss similarly affects the pattern of recovery after the life event or stressor has concluded. Furthermore, subsequent research should focus on how historical loss may shape coping strategies and health behaviors including substance use, sleep, and patterns of social interactions in a way that may contribute to the observed relationships.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National institutes of Health under Award Number U54GM115371. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

We ran the same regression without the 5 individuals who indicated that they had been diagnosed with COVID-19, and the pattern of findings and statistical significance remained unchanged.

References

- 1.Manson S.M., Beals J., Klein S.A. Social Epidemiology of Trauma among 2 American Indian Reservation populations. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95:851–859. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thayer Z., Barbosa-Leiker C., Mcdonell M., Nelson L., Buchwald D., Manson S. Early life trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder and allostatic load in a sample of American Indian adults. Am J Human Biol. 2017;29:3. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beals J., Manson S.M., Croy C., Klein S.A., Whitesell N., Mitchell C.M. Lifetime prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in two American Indian reservation populations. J. Trauma. Stress. 2013;26(4):512–520. doi: 10.1002/jts.21835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullock A., Bell R. Stress, trauma, and coronary heart disease among native Americans. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95(12):2122–2123. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brave Heart M.Y., DeBruyn L.M. The American Indian holocaust: healing historical unresolved grief. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 1998;8(2):56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brave Heart M.Y. The Historical Trauma Response among Natives and its Relationship with substance abuse: a Lakota illustration. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohatt N.V., Thompson A.B., Thai N.D., Tebes J.K. Historical trauma as public narrative: a conceptual review of how history impacts present-day health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014;106:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yellow Horse Brave Heart M, DeBruyn LM The American Indian holocaust: healing historical unresolved grief. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 1998;8(2):56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Running Bear U., Thayer Z., Croy C., Kaufman C., Manson S. The impact of individual and parental American Indian boarding school attendance on chronic physical health of Northern Plains tribes. Fam Community Health. 2019;42(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans-Campbell T. Indian boarding school experience, substance use, and mental health among urban two-Spirit American Indian/Alaska natives. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):421–427. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.701358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heart M.Y., Chase J., Elkins J., Altschul D.B. Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the Americas: concepts, research, and clinical considerations. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):282–290. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gone J.P., Hartmann W.E., Pomerville A., Wendt D.C., Klem S.H., Burrage R.L. The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: a systematic review. Am Psychol. 2019;74(1):20–35. doi: 10.1037/amp0000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitbeck L.B., Walls M.L., Johnson K.D., Morrisseau A.D., McDougall C.M. Depressed affect and historical loss among north American indigenous adolescents. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2009;16(3):16–41. doi: 10.5820/aian.1603.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiechelt S., Gryczynski J., Johnson J.L., Caldwell D. Historical Trauma among urban American Indians: impact on substance abuse and family cohesion. J. Loss Trauma. 2012;17(4):319–336. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2011.616837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Coteau T., Hope D., Anderson J. Anxiety, stress, and health in northern plains native Americans. Behav. Ther. 2003;34(3):365–380. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalala D.E., Trujillo M.H., Hartz G.J., D’Angelo A.J. Indian Health Service; Rockville MD: 1999. Regional differences in Indian health: 1998–1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montana Department of Public Health & Human Services Montana State Health Assessment: A Report on the Health of Montanans. 2019. https://dphhs.mt.gov/Portals/85/ahealthiermontana/2017SHAFinal.pdf Retrieved from.

- 18.Espey D.K., Jim M.A., Cobb N. Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska natives. Am J Pub Health. 2014;104:303–311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brave Heart M., Chase J., Elkins J., Altschul D.B. Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the Americas: concepts, research, and clinical considerations. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43:282–290. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guenzel N., Trauma Struwe L. Historical. Ethnic experience, and mental health in a sample of urban American Indians. J. Am Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020;26(2):145–156. doi: 10.1177/1078390319888266. (107839031988826–56. Web) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kivimäki M., Steptoe A. Effects of stress on the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018;15(4):215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen S., Janicki-Deverts D., Miller G.E. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685–1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albert M.A., Durazo E.M., Slopen N. Cumulative psychological stress and cardiovascular disease risk in middle aged and older women: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Am. Heart J. 2017;192:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L., Zhao Y., Wang Y. The effects of psychological stress on depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(4):494–504. doi: 10.2174/1570159x1304150831150507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammen C., Kim E.Y., Eberhart N.K., Brennan P.A. Chronic and acute stress and the prediction of major depression in women. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26(8):718–723. doi: 10.1002/da.20571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammen C., Henry R., Daley S.E. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68(5):782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dougherty L.R., Klein D.N., Davila J. A growth curve analysis of the course of dysthymic disorder: the effects of chronic stress and moderation by adverse parent-child relationships and family history. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72(6):1012–1021. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendler K.S., Kuhn J.W., Prescott C.A. Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychol. Med. 2004;34(8):1475–1482. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400265x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuner F., Schauer E., Catani C., Ruf M., Elbert T. Post-tsunami stress: a study of posttraumatic stress disorder in children living in three severely affected regions in Sri Lanka. J. Trauma. Stress. 2006;19(3):339–347. doi: 10.1002/jts.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin K.A., Conron K.J., Koenen K.C., Gilman S.E. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol. Med. 2010;40(10):1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser J.P., van Os J., Portegijs P.J., Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006;61(2):229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brave Heart M.Y., DeBruyn L.M. The American Indian holocaust: healing historical unresolved grief. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 1998;8(2):56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denham A.R. Rethinking historical trauma: narratives of resilience. Transcult Psychiatr. 2008;45:391–414. doi: 10.1177/1363461508094673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma in American Indian/native Alaska communities: a multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23:316–338. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxwell K. Historicizing historical trauma theory: troubling the trans-genera- tional transmission paradigm. Transcult Psychiatr. 2014;51:407–435. doi: 10.1177/1363461514531317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohatt N.V., Thompson A.B., Thai N.D., Tebes J.K. Historical trauma as public narrative: a conceptual review of how history impacts present-day health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014;106:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitbeck L.B., Adams G.W., Hoyt D.R., Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2004;33(3–4):119–130. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027000.77357.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conching A.K.S., Thayer Z. Biological pathways for historical trauma to affect health: a conceptual model focusing on epigenetic modifications. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;230:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boutwell B.B., Nedelec J.L., Winegard B. The prevalence of discrimination across racial groups in contemporary America: results from a nationally representative sample of adults. PLoS One. 2017;12(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183356. Published 2017 Aug 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaiser Family Foundation . Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. Poverty Rate by Race/Ethnicity 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kenney M.K., Singh G.K. Adverse childhood experiences among American Indian/Alaska native children: the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s health. Scientifica (Cairo). 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/7424239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirmayer L.J., Brass G.M., Tait C.L. The mental health of aboriginal peoples: transformations of identity and community. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2000;45(7):607–616. doi: 10.1177/070674370004500702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen S., Wills T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.John-Henderson NA, Stellar JE, Mendoza-Denton R, Francis DD. Socioeconomic status and social support: social support reduces inflammatory reactivity for individuals whose early-life socioeconomic status was low. Psychol. Sci. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Sperry D.M., Widom C.S. Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: a prospective investigation [published correction appears in child abuse Negl. 2015 Sep;47:175-6] Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(6):415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roh S., Burnette C.E., Lee K.H., Lee Y.S., Easton S.D., Lawler M.J. Risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms among American Indian older adults: adverse childhood experiences and social support. Aging Ment. Health. 2015;19(4):371–380. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.938603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chong J., Lopez D. Social networks, support, and psychosocial functioning among American Indian women in treatment. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2005;12(1):62–85. doi: 10.5820/aian.1201.2005.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stumblingbear-Riddle G., Romans J.S. Resilience among urban American Indian adolescents: exploration into the role of culture, self-esteem, subjective well-being and social support. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2012;19(2):1–19. doi: 10.5820/aian.1902.2012.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roh S., Brown-Rice K.A., Lee K.H., Lee Y.S., Yee-Melichar D., Talbot E.P. Attitudes toward mental health services among American Indians by two age groups. Community Ment. Health J. 2015;51(8):970–977. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9859-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viseu J., Leal R., de Jesus S.N., Pinto P., Pechorro P., Greenglass E. Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herbell K., Zauszniewski J.A. Stress experiences and mental health of pregnant women: the mediating role of social support. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2019;40(7):613–620. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2019.1565873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tehee M., Buchwald D., Booth-LaForce C., Omidpanah A., Manson S.M., Goins R.T. Traumatic stress, social support, and health among older American Indians: the native elder care study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(5):908–917. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shah K., Kamrai D., Mekala H., Mann B., Desai K., Patel R.S. Focus on mental health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: applying learnings from the past outbreaks. Cureus. 2020;12:3. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sim K., Huak Chan Y., Nah Chong P., Choon Chua H., Wen Soon S. Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010;68(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiang Y., Yang Y., Li W., Zhang L., Zhang Q., Cheung T., Ng C. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiat. 2020;7:228–229. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng C., Cheung M. Psychological responses to outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome: a prospective, multiple time-point study. J. Pers. 2005;73(1):261–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen S., Mermelstein R., Kamarck T., Hoberman H.M. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason I.G., Sarason B.R., editors. Social Support: Theory, Research, and Applications. Martinus Nijhoff. Holland; The Hague: 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Snaith R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-29. Published 2003 Aug 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Repetti R.L., Taylor S.E., Seeman T.E. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002;128(2):330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kraus M.W., Adler N.E., Chen T.W. Is the association of subjective SES and self-rated health confounded by negative mood? An experimental approach. Health Psychol. 2013;32:138–145. doi: 10.1037/a0027343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.John-Henderson N.A., Stellar J.E., Mendoza-Denton R., Francis D.D. Socioeconomic status and social support: social support reduces inflammatory reactivity for individuals whose early-life socioeconomic status was low. Psychol. Sci. 2015;26(10):1620–1629. doi: 10.1177/0956797615595962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rast P., Rush J., Piccinin A., Hofer S.M. The identification of regions of significance in the effect of multimorbidity on depressive symptoms using longitudinal data: an application of the Johnson-Neyman technique. Gerontology. 2014;60:274–281. doi: 10.1159/000358757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gone J.P. “We never was happy living like a Whiteman”: mental health disparities and the postcolonial predicament in American Indian communities. Am J Comm Psychol. 2007;40(3–4):290–300. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gone J.P. Redressing first nations historical trauma: theorizing mechanisms for indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2013;50(5):683–706. doi: 10.1177/1363461513487669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duran E., Duran B. State University of New York; Albany: 1995. Native American Postcolonial Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kirmayer L., Simpson C., Cargo M. Healing traditions: culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian aboriginal peoples. Australasian Psychiat. 2003;11 (Supplement): S15–S23) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gone J.P., Alcantra C. Identifying effective mental health interventions for American Indians and Alaska natives: a review of the literature. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2007;13(4):356–363. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wiechelt S.A., Gryczynski J., Johnson J.L., Caldwell D. Historical Trauma among urban American Indians: impact on substance abuse and family cohesion. J. Loss Trauma. 2012;17(4):319–336. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steptoe A., Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9(6):360–370. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45. Published 2012 Apr 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hackett R.A., Steptoe A. Psychosocial factors in diabetes and cardiovascular risk. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2016;18(10):95. doi: 10.1007/s11886-016-0771-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Itani O., Jike M., Watanabe N., Kaneita Y. Short sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Med. 2017;32:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]