Abstract

In this brief correspondence, we evaluate the potential impact of pivoting from face-to-face supervised to unsupervised home-based exercise programmes to contextualise the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in prostate cancer patients. A meta-analysis was undertaken in fatigue, quality of life, and lean and fat mass outcomes in the four studies included. Our analysis indicates that unsupervised home-based exercise maintains patient-reported outcomes, except for fat mass. In summary, changing to unsupervised exercise is unlikely to provide further benefits on patient-reported and body composition outcomes, but may help maintain initial gains during physical distancing restrictions.

Patient summary

We discuss the potential impacts of transitioning from face-to-face supervised to unsupervised home-based exercise programmes in prostate cancer patients during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Our analysis suggests that patients are likely to maintain patient-reported and body composition benefits from current nonsupervised programmes; however, evolution of exercise delivery to prostate cancer patients is required to continue health and fitness improvement in this group.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, COVID-19, Exercise, Body composition, Patient-reported outcomes

Exercise medicine clinics have had to change their services including those for men with prostate cancer (PCa) due to the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) where face-to-face supervised exercise programmes are required to cease. Unsupervised home-based (ie, off-site) interventions are an alternative method to improve physical activity behaviour in different clinical populations; however, despite being superior to usual care [1], benefits derived from these programmes are modest compared with face-to-face clinic-based programmes and not sustained for prolonged periods in men with PCa at different stages of disease [1], [2]. Moreover, it is undetermined whether a change in programme delivery (ie, face-to-face clinic-based to unsupervised home-based programmes) would preserve clinical outcomes. These outcomes are relevant as the gains achieved with supervised periods of exercise could be significantly reduced, resulting in loss of exercise adaptations and decline in psychological and metabolic health.

In this brief correspondence, we analyse the effects of change from face-to-face supervised to unsupervised home-based exercise programmes on fatigue, quality of life (QoL), and body composition in men with PCa. Although none of the studies were performed during a viral pandemic, we highlight and contextualise our findings to their application for the COVID-19 pandemic, where face-to-face interventions have been restricted. This information will help provide a rationale for the delivery of exercise medicine to PCa patients in clinical practice in the current COVID-19 landscape.

A systematic review was undertaken in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effects of supervised resistance-based exercise programmes with subsequent change to a nonsupervised exercise intervention in PCa patients. Data were extracted from four manuscripts [3], [4], [5], [6] describing three RCTs in men with PCa on androgen suppression therapy (AST) or previously treated with AST, which included fatigue, QoL, and body composition (ie, fat and lean mass) from the completion of face-to-face supervised and unsupervised home-based periods. The study selection procedure and results, and the main characteristics are described in the Supplementary material and provided in Table 1. We undertook a meta-analysis using a random-effect model and the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method. Pooled-effect estimates were obtained from within-group values. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q test and expressed by I2.

Table 1.

Study characteristics: cancer therapy duration, demographic and clinical characteristics, sample size, supervised and nonsupervised exercise prescription, and outcomes assessed.

| Author (year) | Cancer therapy duration | Demographical and clinical characteristics | Face-to-face supervised exercise period | Unsupervised home-based exercise period | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galvão et al (2014) [3] | Previous AST duration of ∼12 mo with time since its cessation of 38 mo | Age: 71.4 yr; II–IV; Previous AST and radiotherapy |

Combined resistance and aerobic training: n = 50, 2 sessions per week for 24 wk; RT: 2–4 sets of 6–12 RM; AT: 20–30 min at 70–85% HR |

24 wk; booklet with detailed information about a home exercise prescription including resistance, aerobic, and flexibility exercises | Fat mass, lean mass, SF-36 a |

| Taaffe et al (2017) [4]b | Minimum exposure to AST of 2 mo and anticipated to receive AST for the subsequent 12 mo | Age: 68.8 yr; Localised and nodal metastases; Gleason score: 7.8; AST AST plus radiotherapy AST plus antiandrogen AST plus surgery |

Combined resistance and aerobic training: n = 54, 2 sessions per week for 24 wk; AT: 20–30 min at 60–85% HR; RT: 2–4 sets of 6–12 RM |

24 wk; home-based programme that recommended 150 min of aerobic exercise per week and resistance exercise using body weight and resistance bands | EORTC QLQ-C30Fatiguec |

| Ndjavera et al (2020) [5] | Patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancer and beginning AST treatment | Age: 72.0 yr; Locally advanced and metastatic patients; Gleason score range from 6 to 10; ASTAST plus radiotherapy |

Combined resistance and aerobic training: n = 24, 2 sessions per week for 12 wk; AT: 6 bouts of 5 min at 55–85% HR; RT: 2–4 sets of 10 reps at 11–15 RPE |

12 wk; patients were instructed to continue exercising and maintain self-directed levels of physical activity | Fat mass, FACT-P a, FACIT-Fatigue c |

| Newton et al (2019) [6]b | Minimum exposure to AST of 2 mo and anticipated to receive AST for the subsequent 12 mo | Age: 69.0 yr; Localised and nodal metastases; Gleason score: 7.8; AST AST plus radiotherapy AST plus antiandrogen |

Combined resistance and aerobic training:n = 50, 2 sessions per week for 24 wk; AT: 20–30 min at 60–85% HR; RT: 2–4 sets of 6–12 RM | 24 wk; home-based programme that recommended 150 min of aerobic exercise per week and resistance exercise using body weight and resistance bands | Fat mass, lean mass |

AST = androgen suppression therapy; AT = aerobic training; EORTC QLQ-C30 = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30; FACIT = Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy; FACT-P = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Prostate; HR = hear rate; RM = repetitions maximum; RPE = rate of perceived exertion; RT = resistance training; SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Survey.

Included in quality-of-life meta-analysis.

Papers derived from the same trial.

Included in fatigue meta-analysis.

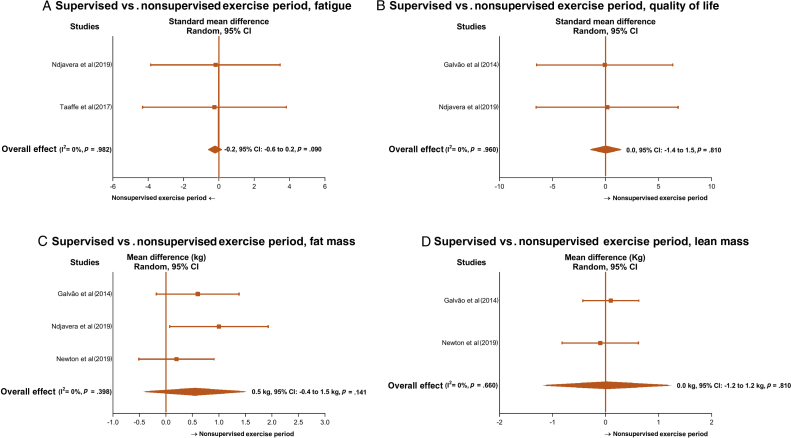

One-third of men undergoing AST experience fatigue due to associated depression, anxiety, pain, and insomnia, resulting in reduced QoL. Despite the maintenance of patient-reported outcomes during unsupervised home-based programmes (Fig. 1A and 1B), issues related to the participants’ baseline levels and programme design may affect the interpretation of our findings. In the included studies, participants mostly presented with low baseline levels of fatigue and high levels of QoL, and this may have attenuated further change from the exercise programme during the unsupervised period. Thus, we may need to consider that fatigue and QoL are likely to be affected during the pandemic period in patients with higher fatigue levels and poor QoL. This concern is not only because of the distress associated with time on AST or fears related to tumour recurrence, but also because of distancing from family and friends, and fears associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, most unsupervised home-based programmes require participants to have a self-controlled physical activity habit. Although this might work for those with regular exercise habits, it is unlikely to be generalised to all patients. Thus, current unsupervised models based on a usual weekly exercise volume (eg, 150 min/wk) or self-directed physical activity may not fit patient needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. A redesigned home-based exercise programme leveraging the rapidly developing technology resources may help facilitate and assist participants in overcoming barriers related to exercise practice, such as lack of self-discipline, safety and monitoring, time, and treatment-related fatigue. Digital health facilitating technology might include the following:

-

1

Wearable biosensors (eg, heart rate, physical activity, steps, and distance)

-

2

Digital exercise prescription platforms providing the exercise programme and instructions, and recording exercises completed on the patient’s smart device or computer

-

3

Video chat with a qualified exercise professional to monitor and support the patient

Fig. 1.

Mean difference and standard mean difference effects of face-to-face exercise programmes compared with unsupervised home-based exercise programmes on (A) fatigue, (B) quality of life, (C) fat mass, and (D) lean mass. Squares represent study-specific estimates and diamonds represent pooled estimates of random-effect meta-analysis. CI = confidence interval.

During face-to-face supervised exercise, studies reported positive effects on body fat (range: –2.6 to –0.6 kg) and lean mass (range: 0.1–0.7 kg) [3], [5], [6]. However, our analysis reveals that PCa patients were more likely to increase fat mass during follow-ups with unsupervised programmes, although lean mass was preserved (Fig. 1C and 1D). Considering the maintenance of physical activity levels and nutritional status reported in those studies [3], [6], our findings suggest that body fat is likely to be increased during COVID-19 restriction, potentially adversely affecting metabolic health and disease prognosis [7]. Although there is evidence that patients on AST may be less likely to develop COVID-19 than PCa patients not receiving AST [8], poor body composition and reduced physical activity levels can contribute to poorer disease prognosis, altering systemic and cellular factors and increasing the incidence of comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension [9]. Thus, our results highlight the need for different exercise strategies such as an adequate increase of exercise stimulus (volume or intensity) to balance energy expenditure during physical activity restrictions or for facilitating intervention delivery as outlined above using different resources such as exercise smartphone Apps and online programmes (eg, telehealth). This may help provide instructions and feedback to help maintain patient motivation during the outbreak and avoid physical inactivity. Therefore, a higher exercise stimulus and increased contact with patients are likely to help maintain exercise adherence and counteract expected weight gain during self-quarantine [10].

In summary, despite the relatively small number of studies and patients in our meta-analysis, the direction of our results and the change of habits during the lockdown [10] are a concern when viewed in the context of the current worldwide situation. Changing from face-to-face to unsupervised self-directed home-based exercise programmes is unlikely to provide further benefits on fatigue, QoL, and body composition in patients with PCa during physical distancing restrictions, but may help with maintenance. Therefore, use of various technologies to keep patients motivated during self-quarantine and an increase in exercise stimulus to counteract physical distancing restrictions are some of our suggestions for the current COVID-19 landscape to avoid physical inactivity. These measures are necessary to guarantee the continuation of appropriate and targeted exercise medicine delivery to PCa patients.

Author contributions: Pedro Lopez had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Lopez, Taaffe, Newton, Galvão.

Acquisition of data: Lopez.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Lopez, Taaffe, Newton, Spry, Shannon, Frydenberg, Saad, Galvão.

Drafting of the manuscript: Lopez, Taaffe, Newton, Spry, Shannon, Frydenberg, Saad, Galvão.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Lopez, Taaffe, Newton, Spry, Shannon, Frydenberg, Saad, Galvão.

Statistical analysis: Lopez.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: None.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Pedro Lopez certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: Pedro Lopez is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence (CRE) in Prostate Cancer Survivorship Scholarship. Daniel A. Galvão and Robert U. Newton are funded by an NHMRC CRE in Prostate Cancer Survivorship. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation. Sponsors were not involved in the study design, analysis or interpretation of data, manuscript writing, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2020.09.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Buffart L.M., Kalter J., Sweegers M.G. Effects and moderators of exercise on quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 34 RCTs. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galvão D.A., Newton R.U., Girgis A. Randomized controlled trial of a peer led multimodal intervention for men with prostate cancer to increase exercise participation. Psychooncology. 2018;27:199–207. doi: 10.1002/pon.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galvão D.A., Spry N., Denham J. A multicentre year-long randomised controlled trial of exercise training targeting physical functioning in men with prostate cancer previously treated with androgen suppression and radiation from TROG 03.04 RADAR. Eur Urol. 2014;65:856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taaffe D.R., Newton R.U., Spry N. Effects of different exercise modalities on fatigue in prostate cancer patients undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: a year-long randomised controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2017;72:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ndjavera W., Orange S.T., O’Doherty A.F. Exercise-induced attenuation of treatment side-effects in patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancer beginning androgen-deprivation therapy: a randomised controlled trial. BJU Int. 2020;125:28–37. doi: 10.1111/bju.14922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton R.U., Galvão D.A., Spry N. Exercise mode specificity for preserving spine and hip bone mineral density in prostate cancer patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:607–614. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King A.J., Burke L.M., Halson S.L., Hawley J.A. The challenge of maintaining metabolic health during a global pandemic. Sports Med. 2020;50:1233–1241. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01295-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montopoli M., Zumerle S., Vettor R. Androgen-deprivation therapies for prostate cancer and risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2: a population-based study (N = 4532) Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1040–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith M.R., Saad F., Egerdie B. Sarcopenia during androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3271–3276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zachary Z., Brianna F., Brianna L. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.