Branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism plays a significant role in many biological activities beyond protein synthesis. Spore germination initiates the first stage of vegetative growth, which is critical for the virulence of pathogenic fungi. In this study, we demonstrated that the keto-acid reductoisomerase MrILVC, a key enzyme for BCAA biosynthesis, from the insect-pathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii is associated with conidial germination and fungal pathogenicity. Surprisingly, the germination of the ΔMrilvC mutant was restored when supplemented with the intermediates of BCAA metabolism rather than three BCAAs. The result was significantly different from that of plant-pathogenic fungi. Therefore, this report highlights that the intermediates in BCAA biosynthesis are indispensable for conidial germination of M. robertsii.

KEYWORDS: branched-chain amino acid, intermediates, conidial germination, Metarhizium robertsii

ABSTRACT

Metarhizium spp. are well-known biocontrol agents used worldwide to control different insect pests. Keto-acid reductoisomerase (ILVC) is a key enzyme for branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) biosynthesis, and it regulates many physiological activities. However, its functions in insect-pathogenic fungi are poorly understood. In this work, we identified MrilvC in M. robertsii and dissected its roles in fungal growth, conidiation, germination, destruxin biosynthesis, environmental stress response, and insecticidal virulence. BCAA metabolism affects conidial yields and germination. However, BCAAs cannot recover the conidial germination of an MrilvC-deficient strain. Further feeding assays with intermediates showed that some conidia of the ΔMrilvC mutant start to germinate. Therefore, it is the germination defect that causes the complete failures of conidial penetration and pathogenicity in the ΔMrilvC mutant. In conclusion, we found intermediates in BCAA biosynthesis are indispensable for Metarhizium robertsii conidial germination. This study will advance our understanding of the fungal germination mechanism.

IMPORTANCE Branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism plays a significant role in many biological activities beyond protein synthesis. Spore germination initiates the first stage of vegetative growth, which is critical for the virulence of pathogenic fungi. In this study, we demonstrated that the keto-acid reductoisomerase MrILVC, a key enzyme for BCAA biosynthesis, from the insect-pathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii is associated with conidial germination and fungal pathogenicity. Surprisingly, the germination of the ΔMrilvC mutant was restored when supplemented with the intermediates of BCAA metabolism rather than three BCAAs. The result was significantly different from that of plant-pathogenic fungi. Therefore, this report highlights that the intermediates in BCAA biosynthesis are indispensable for conidial germination of M. robertsii.

INTRODUCTION

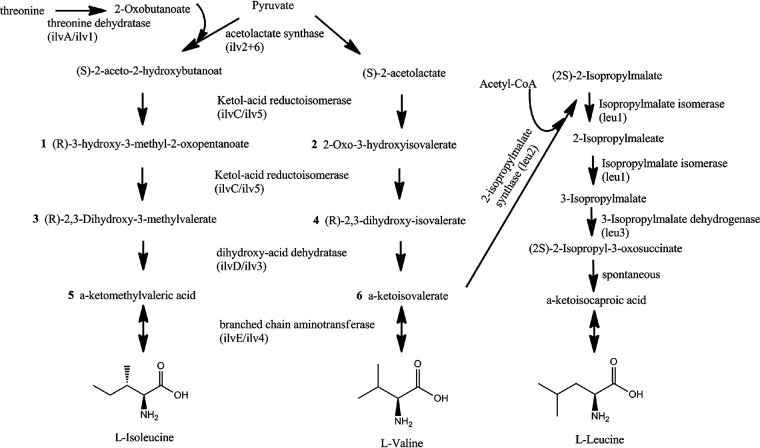

Amino acid metabolism plays an important role in the growth, development, and reproduction of animals, plants, and microorganisms. Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) consist of isoleucine (Ile), leucine (Leu), and valine (Val) and account for about 18% of amino acids and 63% of hydrophobic amino acids in proteins of many organisms (1). BCAAs are de novo synthesized in bacteria, fungi, and plants. Animals do not synthesize BCAAs but can absorb them from their diet. Thus, BCAA synthesis enzymes have been successfully targeted for herbicides, fungicides, and antimicrobial agents (2–4). Ile and Val are biosynthesized by the same enzymes in two parallel pathways (Fig. 1). These reaction steps are catalyzed by acetolactate synthases (AHAS, ILV2, and ILV6), ketol-acid reductoisomerase (KARI, ILVC, or ILV5), dihydroxy-acid dehydratase (DHAD, ILVD, or ILV3), and branched-chain aminotransferase (BCAT and ILVE). Ile and Val each have only one pathway, whereas Leu can be either created through pyruvate or synthesized from Val by reverse reaction of BCAT (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Biosynthesis routes of BCAAs. Abbreviations of the enzyme-coding genes are given in brackets. The pathway was modified according to the KEGG database (18).

BCAAs and various catabolic products not only serve as nutrients but also act as signaling molecules in mediating protein synthesis and metabolic homeostasis and playing roles in pathophysiology (1, 5). Threonine deaminase ILV1, the first enzyme in the biosynthesis of Ile, is essential for morphogenesis, appressorium formation, invasive hyphal growth, and pathogenicity in the plant-pathogenic fungi Magnaporthe oryzae (6) and Fusarium graminearum (7). Likewise, the acetolactate synthase Ilv2 and Ilv6 deletion mutants of M. oryzae (8) and F. graminearum (9) are defective in mycelial growth, conidial morphogenesis, appressorial penetration, and fungal pathogenicity. Studies of ketol-acid reductoisomerase ILV5 (10) and dihydroxy-acid dehydratase ILV3 (11) showed that they are crucial for BCAA biosynthesis, deoxynivalenol production, and full virulence of F. graminearum. Moreover, isopropylmalate dehydrogenase LEU2 (12) and isopropylmalate isomerase LEU1 (13), which catalyze the first two reactions of Leu biosynthesis, are both essential for fungal vegetative growth, conidiogenesis, and pathogenicity.

Although BCAA metabolism was fully investigated in plant-pathogenic fungi, its functions in entomopathogenic fungus are still uncharted. The majority of Metarhizium species are entomopathogens that act as regulators of insect populations in nature (14). Metarhizium spp. are well-known biocontrol agents used worldwide to control different insect pests, with particular success in controlling spittlebugs on alfalfa and sugarcane in Brazil and plague locusts in Africa, as well as mosquito vectors of malaria (15). This work aimed to unveil the effects of ILVC on fungal growth, germination, destruxin (DTX) production, environmental stress responses, and virulence in M. robertsii, a fungus model for investigating the mechanisms of pathogenesis for insect and multiple lifestyle transitions.

RESULTS

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of MrilvC in M. robertsii.

Through BLASTP searches of the genome sequences of M. robertsii, we identified that MAA_03009 (GenBank accession number XP_007819198.1) shares high amino acid sequence homology with F. graminearum FgIlv5 (10) (XP_011319056.1, 86.9% identity). The putative encoding gene was annotated as MrilvC, and it is 1,513 bp in length and has four predicted introns. MrilvC encodes 401 amino acids.

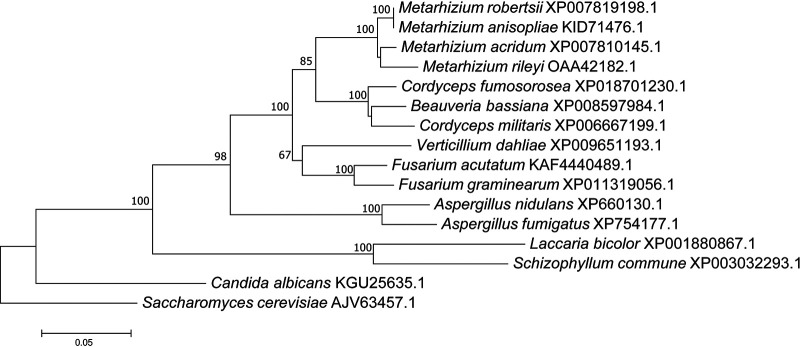

A phylogenetic tree of ILVC proteins from Metarhizium spp. and related fungal species was constructed with Saccharomyces cerevisiae as an outgroup. All ILVC proteins from the genus Metarhizium fell into an independent group (100% bootstrap value) (Fig. 2). These Metarhizium ILVC proteins are closely related to ILVC proteins from Cordycipitaceae fungi, including Beauveria bassiana, Cordyceps militaris, and C. fumosorosea (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic tree constructed with different fungal ILVC proteins. Bootstrap values greater than 50% are indicated on the tree. Numbers at the nodes indicate the bootstrap values. The bar markers indicate genetic distances, which are proportional to the number of amino acid substitutions.

BCAA metabolism contributes to mycelial growth, and MrilvC deficiency can be rescued by exogenous supplementation of Ile and Val.

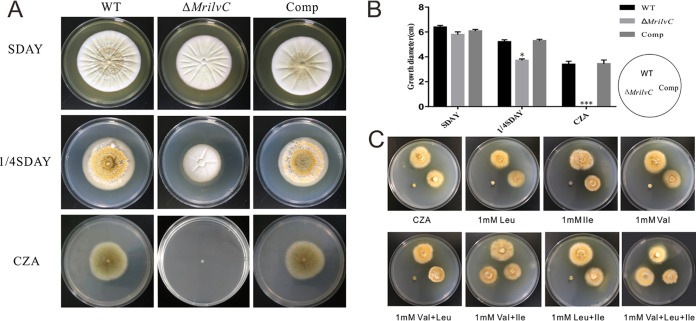

Deletion of MrilvC resulted in BCAA auxotrophy in M. robertsii. Wild-type (WT), MrilvC-deficient (ΔMrilvC), and complemented (Comp) strains were grown on SDAY (40 g glucose, 10 g peptone, 10 g yeast extract powder, and 15 g agar for 1 liter) plates. After being cultured for 5 days, a 4-mm mycelial plug from each plate was transferred to SDAY, 1/4 SDAY, and CZA (3 g NaNO3, 1 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g KCl, 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O, 30 g sucrose, and 15 g agar for 1 liter) plates for 14 days. As shown in Fig. 3A, the ΔMrilvC mutant was unable to grow on CZA plates containing no amino acids. However, it could grow on 1/4 SDAY medium despite the colony being smaller than that of the WT (Fig. 3B). When placed on full-nutrition SDAY plates, the auxotrophy was fully recovered. The complemented strain showed no significant differences from the WT on different media.

FIG 3.

Fungal growth of ΔMrilvC mutant using different media. (A) Comparison of the ΔMrilvC mutant with WT and Comp strains in colony morphology. (B) The colony diameters were measured and subjected to statistical analysis. (C) Exogenous Val and Ile could restore the growth defect of the MrilvC mutant on CZA plates. Error bars represent standard deviations. Significance of the differences was analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001). Bars denote standard errors from three repeated experiments.

BCAAs include three amino acids; we further determined whether individual or multiple amino acid starvation is important to fungal growth. Ile, Leu, or Val (1 mM) was separately added to CZA medium, and the results showed that the ΔMrilvC mutant could not grow on them. Likewise, exogenous supplementation of Val and Leu or Leu and Ile had the same results, whereas Val and Ile, or all three amino acids, could rescue the growth defect of the ΔMrilvC mutant (Fig. 3C). Leu is not essential, which is due to the reverse reaction of Val to α-ketoisovalerate, a precursor of Leu, catalyzed by BCAT (Fig. 1). These results suggested that MrilvC plays a crucial role in fungal growth, and the supplementation of two amino acids (Val and Ile) is enough to restore the growth impairment of the ΔMrilvC mutant, which is consistent with the observation of the ΔFgIlv5 mutant in F. graminearum (10).

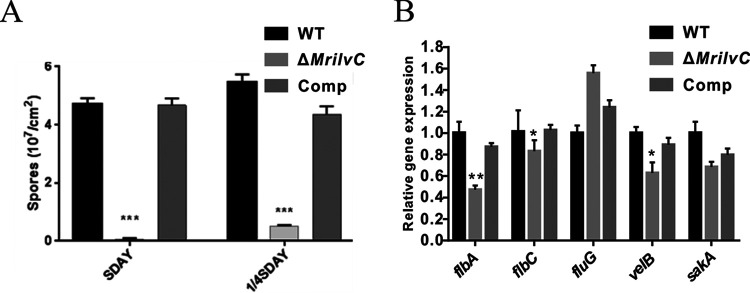

BCAA metabolism affects conidial yields and germination.

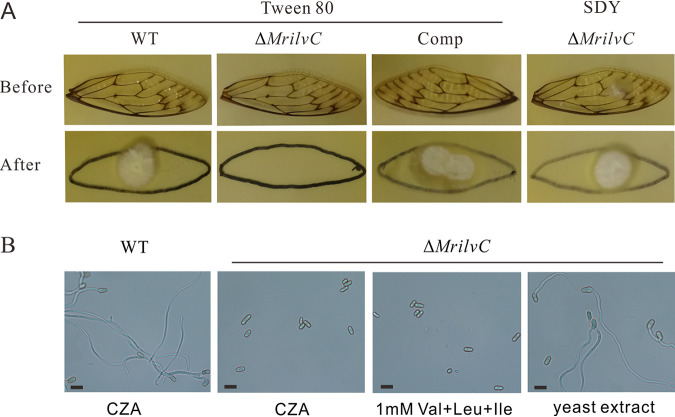

As a result of the growth defect of ΔMrilvC on CZA medium, fungal conidiogenesis was measured on SDAY and 1/4 SDAY plates. In contrast to the WT and complemented transformant, conidial yields of the ΔMrilvC mutant were dramatically decreased (Fig. 4A). Additional gene expression analysis showed that most conidiation-related genes (19, 41, 42) were downregulated (Fig. 4B). To investigate the effect of BCAA metabolism on fungal penetration, we used the wings from cicada (Cryptotympana atrata) to simulate insect cuticle. Spores were dripped on cicada wings placed on SDAY plates and grown for 3 days to allow penetration. Once the fungus has penetrated the wings, colonies would be formed after removing the wings. The results revealed that ΔMrilvC conidia failed to penetrate the insect cuticle, in contrast to WT and Comp conidia (Fig. 5A). However, when ΔMrilvC conidia were prepared by an aqueous solution of SDY (SDAY without agar), their host penetration ability was restored. Hence, BCAA metabolism noticeably influences fungal penetration, which may be due to their failure to germinate on insect cuticle or in nutrient-poor media.

FIG 4.

Deletion of MrilvC leads to decreased conidiogenesis. (A) Conidial yields of different strains cultured on SDAY and 1/4 SDAY for 14 days. (B) The qRT-PCR analysis of sporulation-related genes in 2.5-day SDAY colonies. GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was used as an internal control. Significance of the differences was analyzed by ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Bars denote standard errors from three repeated experiments.

FIG 5.

MrilvC is crucial for conidial germination. (A) ΔMrilvC mutant could not penetrate the wings from cicada. Conidia were inoculated on wings for 3 days (before), then the wings were removed and the remaining plates were cultured for additional 3 days (after). (B) Microscopy observation of conidial morphology at 36 h postinoculation in liquid media. Bar, 5 μm. The penetration and germination tests were repeated three times with similar results.

Although the mycelia of the ΔMrilvC mutant could grow on CZA medium supplied with all three BCAAs, its conidia were still unable to germinate (Fig. 5B). This result was different from the observation that the conidia of the ΔFgIlv5 mutant were able to germinate when cultures were supplemented with Ile and Val in F. graminearum (10), but 1% yeast extract was sufficient to stimulate germination of ΔMrilvC conidia. Thus, Metarhizium and Fusarium may have varied conidial germination mechanisms, and some components in yeast extract may be necessary for germination besides BCAAs.

The intermediates in BCAA biosynthesis are essential for conidial germination.

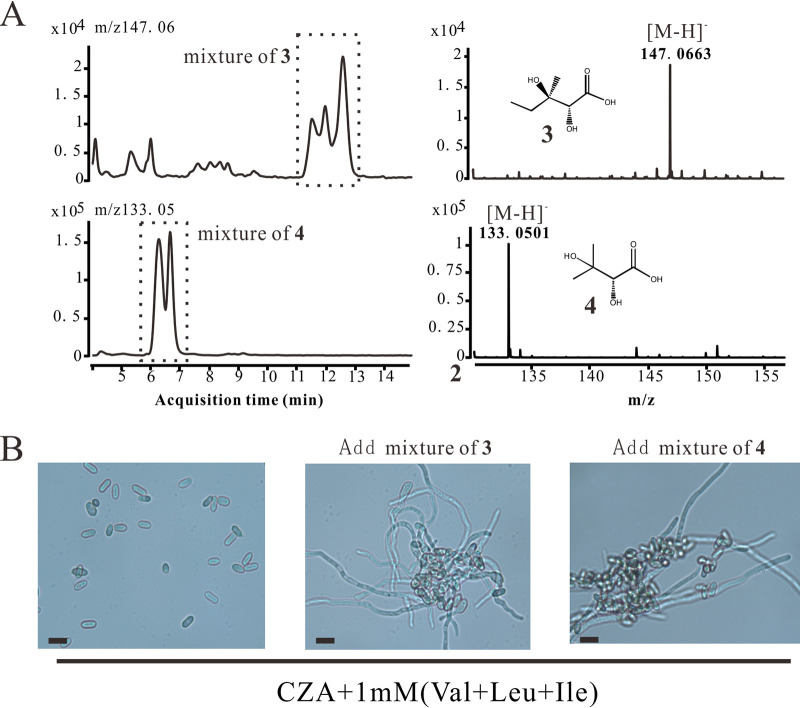

By analysis of the BCAA biosynthetic pathway, we found that six intermediates were missing from the MrilvC-deficient strain, with compound numbers as follows 1, (R)-3-hydroxy-3-methyl-2-oxopentanoate; 2, 2-oxo-3-hydroxyisovalerate; 3, (R)-2,3-dihydroxy-3-methylvalerate; 4, (R)-2,3-dihydroxy-isovalerate; 5, α-ketomethylvaleric acid; and 6, α-ketoisovalerate. Compounds 5 and 6 can be generated by IlvE in the presence of Ile and Val. Considering the results presented above (Fig. 5B), compounds 5 and 6 are not indispensable for conidial germination. Next, the yeast extract was thoroughly screened using high-performance liquid chromatography tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry (HPLC-HRMS) in negative ionization mode (Fig. 6). We only detected putative intermediates 3 and 4 by extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) of m/z 147.0657 ([M−H]− for compound 3, C6H11O4−) and m/z 133.0501 ([M−H]− for compound 4, C5H9O4−), demonstrating that they may play an important role in fungal germination. Unfortunately, no commercial standards were available to identify them. As Fig. 6A showed, there are two isomers of compound 3; they may be mevalonic acid and pantoate. The other isomeric compound of metabolite 4 may be deoxyribose. These isomers are all common primary metabolites in fungi.

FIG 6.

ΔMrilvC mutant is able to germinate with concurrent supplementation with BCAAs and compound 3 (or 4). (A) EIC (left) and mass spectra (right) of compounds 3 and 4. (B) Feeding assay of ΔMrilvC mutant with a mixture of compound 3 or 4. Bar, 5 μm. The feeding experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Of compounds 3 and 4, which one contributes to germination? To this end, we tried to isolate them according to their retention time by HPLC. However, in light of the similar polarity of two intermediates with isomers, we just obtained their respective mixtures. Feeding assays with either of them showed that some conidia of the ΔMrilvC mutant start to germinate (Fig. 6B).

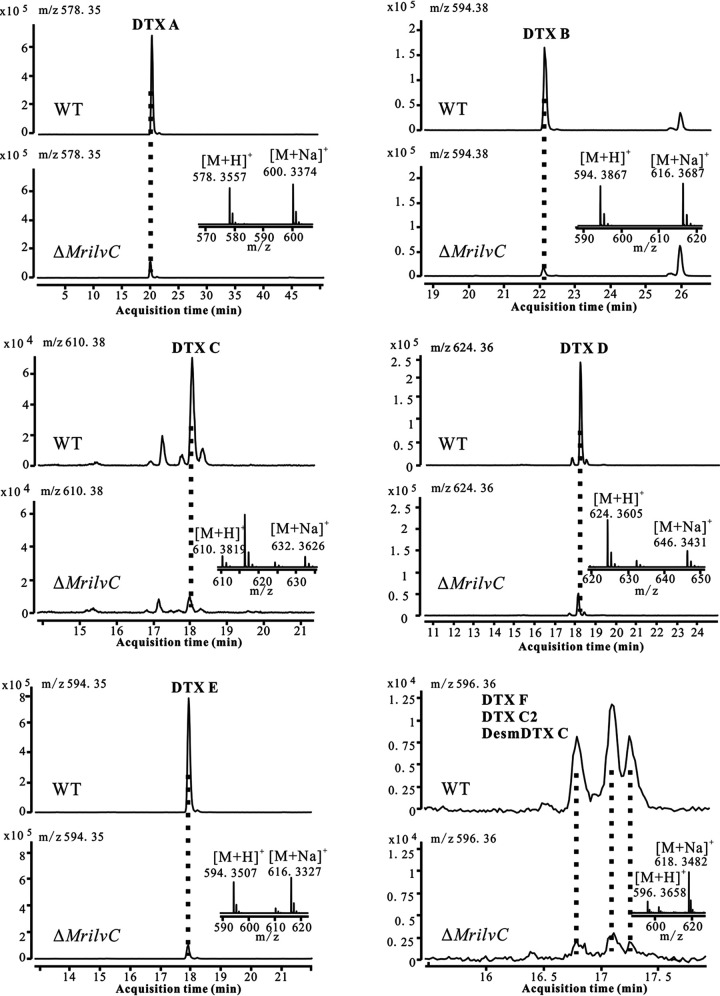

Disruption of MrilvC reduces the production of destruxins.

DTXs have been known as insecticidal agents and are mainly isolated from Metarhizium spp. More than 40 DTXs have been identified so far (20). They are cyclic hexadepsipeptides comprising five amino acid units and a hydroxy acid. For DTX A to F, the sequence of amino acids is proline, Ile, N-methylvaline (N-MeVal), N-methylalanine, and β-alanine, in which two BCAAs are included in the structures. To probe the role of MrilvC in DTXs, the WT and gene-deficient strains were cultured in SDY medium, and their mycelial extracts were analyzed by HPLC-HRMS. The results showed that six DTXs (A to F) and two isomers of DTX F were all significantly decreased in the ΔMrilvC mutant (Fig. 7). Our data indicate that BCAA metabolism has an important effect on the biosynthesis of DTXs.

FIG 7.

EIC and mass spectra for DTXs A to F. The retention times of DTXs A to E were 20.06 min, 22.19 min, 18.03 min, 18.11 min, and 17.96 min, respectively. DTX F and its two isomers were eluted as three peaks (16.83 min, 17.13 min, and 17.27 min).

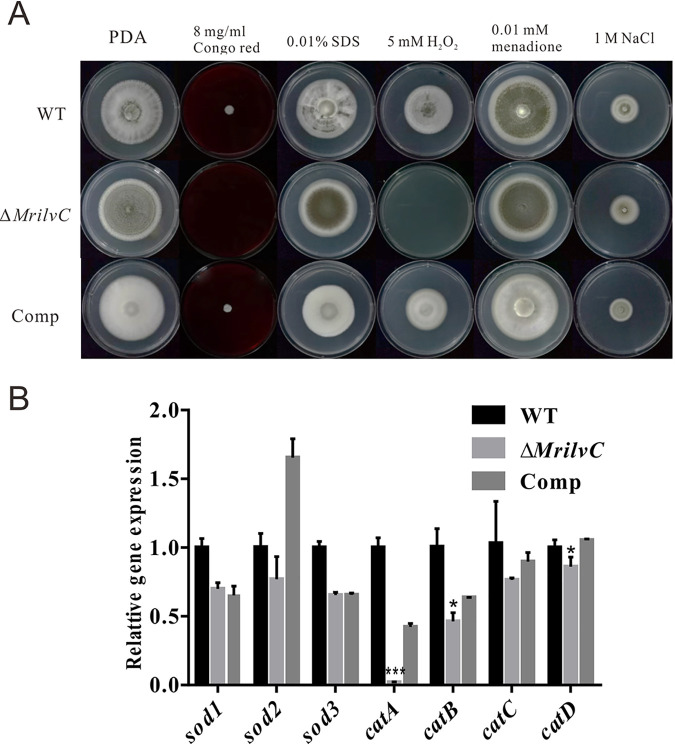

BCAA metabolism is crucial for fungal cell wall integrity as well as for resistance to oxidative stress.

We determined the contribution of MrilvC in enforcing fungal cell wall and membrane integrity. Corresponding results revealed that Congo red (cell wall inhibitor) but not SDS (cell membrane disrupter) has an inhibitory effect on the growth of the ΔMrilvC mutant (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the gene deletion mutant displayed sensitivity toward oxidative stress mediated by H2O2 instead of menadione. Lack of MrilvC had no adverse effect on osmotic stress caused by NaCl. Although the ΔMrilvC mutant is tolerant of menadione, our quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) results indicated that three antioxidative enzymes (21, 22, 43) have lower transcript expression levels than WT and Comp strains (Fig. 8B).

FIG 8.

Phenotypes of the mutants under various stress conditions. (A) Colony morphology of ΔMrilvC mutant compared with that of WT and Comp strains on PDA amended with compounds causing various cellular stresses. (B) Relative expression profiles of selected antioxidant genes (Sod, superoxide dismutase; Cat, catalase). GAPDH was used as an internal control. Significance of the differences was analyzed by ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001). Bars denote standard errors from three repeated experiments.

Deletion of MrilvC impairs fungal full virulence.

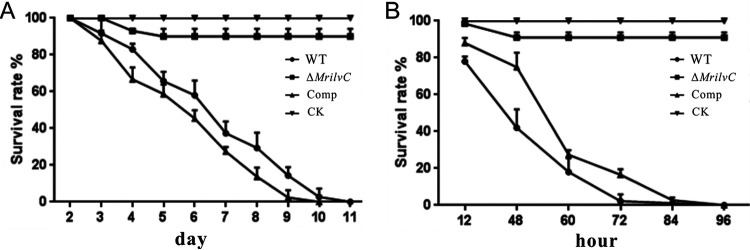

To examine whether MrilvC is involved in fungal pathogenicity, we performed insect bioassays by both immersion and injection of wax moth larvae with conidial suspensions of WT, ΔMrilvC, and Comp strains. The results indicated that, in contrast to the WT and Comp strains, the MrilvC-deficient mutant lost its ability to kill insects in topical infection and injection assays (Fig. 9). Thus, MrilvC is required for the full virulence of M. robertsii.

FIG 9.

Insect bioassays. (A) Survival of wax moth larvae after topical infection. (B) Survival of wax moth larvae following injection. CK, control insects were treated with 0.05% Tween 80. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

BCAAs and their catabolic products not only serve as substrates for proteins and secondary metabolites synthesis but also act as signaling molecules (1, 23). In this study, the ΔMrilvC mutant was BCAA auxotrophic, and exogenous Val and Ile could compensate for the defective growth of the MrilvC-deficient mutant on CZA (poor nutrition) medium. However, although the growth defects of the ΔMrilvC mutant can be fully rescued on SDAY (rich nutrition) plates, the conidial yields of the ΔMrilvC mutant were remarkably decreased. Moreover, in contrast to results on SDAY, the ΔMrilvC mutant exhibited a higher conidiogenesis on 1/4 SDAY. These results demonstrated that the low sporulation may not be due to the depletion of BCAAs. In fact, our gene expression analysis revealed the downregulation of most conidiation-related genes.

Surprisingly, the ΔMrilvC mutant failed to germinate on CZA complemented with three BCAAs, which is opposite the result of a previous study in F. graminearum (10). The components of host wings are mainly fatty acids, esters, peptides, glucose, and a few amino acids (24, 25). Therefore, the failure of germination reasonably explained why the ΔMrilvC mutant could not penetrate the wings from cicada. The germination of ΔMrilvC was recovered in SDY or 1% yeast extract, which implied that some metabolites in yeast extract are essential for germination.

By analysis of BCAA biosynthesis and HPLC purification, we harvested the mixtures of intermediates 3 and 4, and the isomers in compound 3 do not overlap that in compound 4. Feeding assays showed that some conidia had germinated when adding a mixture of compound 3 or 4. However, the germination rate was low, probably owing to the low concentration of effective metabolites 3 and 4 in mixtures and/or the biotransformations of compounds 3 and 4 to 5 and 6 by MrILVD, respectively. The process of resting conidial active germination, when conditions are favorable, includes isotropic growth (volume swelling), cell polarization, polar tube formation, and hyphal growth (26). Large quantities of transcripts involved in material and energy metabolisms are stored in dormant conidia and are quickly translated to proteins during isotropic growth, resulting in a marked increase in conidial size. After isotropic growth, the polarizome (multiprotein complex) regulates cell polarity through its effects on actin as well as the GTP-binding proteins (27). As a result of polarized growth, the hyphal tip emerges at the site of polarization (germ tube formation). Spitzenkörper (SPK) is a cluster of vesicles with a core rich in ribosomes, chitosomes, actin, and an amorphous matrix. The SPK locates on the tip of hypha and plays a role in hyphal apical growth (28). Thus, it is speculated that the germination defect of the ΔMrilvC mutant occurs in the first two phases. The exact functions of intermediates 3 and 4 in germination deserve further investigation.

Fungal secondary metabolites are regulated by complex metabolisms of substance and energy. Metarhizium fungi produce many secondary metabolites, and DTXs are major toxic compounds that have antifeedant activities against crop pests (29) and cause insect tetanic paralysis (30). Two BCAAs, Ile and Val, are important precursors for DTXs A to F. It was found that the biosynthesis of DTXs is significantly controlled by MrILVC. Likewise, BCAA metabolism also plays a role in red pigment aurofusarin formation in F. graminearum (9–12), although BCAAs are not its precursors. Thus, it is possible that the levels of some other secondary metabolites also have changed in the ΔMrilvC mutant.

During infection, pathogenic fungi endure host-associated stresses, including osmotic and oxidative stresses (31). Cell wall integrity contributes to multistress responses by fortifying the cell wall and repairing cell wall damage after stress (32). Disruption of MrilvC resulted in increased susceptibilities to cell wall inhibitor and H2O2-induced oxidative stress even with sufficient nutrients. However, no obvious changes were observed in cell membrane inhibitor as well as menadione-induced oxidative and osmotic stresses. These phenotypes were partly inconsistent with F. graminearum (10). Further qRT-PCR results showed that the expression levels of three catalase genes were reduced in the ΔMrilvC mutant. From these results, MrilvC has an influence on stress tolerance.

Like BCAA biosynthetic genes in plant-pathogenic fungi, the mutant lacking MrilvC lost virulence against the insect host. The experiment of cuticle infection showed that the conidia from the ΔMrilvC mutant were unable to germinate on the cuticle by microscopic observation. Intriguingly, the mortality of direct injection was similar to that of cuticle infection. Insect hemolymph contains inorganic solutes, amino acids, proteins, and other unknown constituents (33, 34). We inferred that the lack of compounds 3 and 4 in hemolymph leads to the compromise of conidial germination and impairs the full virulence.

In conclusion, beyond the nutrients for protein synthesis, MrilvC plays critical roles in controlling sporulation, conidial germination, DTX production, stress protection, and pathogenesis. Most importantly, we found that the intermediates in BCAA biosynthesis are indispensable for fungal germination in M. robertsii. These results contribute to our knowledge for understanding the relationship of BCAA metabolism with fungal growth, development, and pathogenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strain and maintenance.

M. robertsii strain ARSEF 2575 was selected as the wild type for transformation in this study. The WT and mutant strains were grown on SDAY (40 g glucose, 10 g peptone, 10 g yeast extract powder, and 15 g agar for 1 liter), 1/4 SDAY (SDAY nutrients diluted to 1/4), or CZA (3 g NaNO3, 1 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g KCl, 0.01 g FeSO4·7H2O, 30 g sucrose, and 15 g agar for 1 liter) medium at 25°C. Escherichia coli Top10 and Agrobacterium tumefaciens AGL-1 were used for vector construction and fungal transformation, respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis of ILVCs.

To construct the phylogenetic tree of ILVC proteins, homologous ILVC sequences from different fungal species were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). ILVC sequences were aligned using ClustalX, and then a neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was generated using MEGA 7.0 software (35, 36).

Construction of MrilvC deletion and complement mutants.

Gene knockout was performed by homologous recombination via Agrobacterium-mediated fungal transformation as previously described (37, 38). Approximately 1-kb flanking sequences were cloned and then inserted into the corresponding sites of the binary vector pDHt-bar (conferring resistance against glufosinate ammonium [GA]) using recombinase (Vazyme, China). Besides GA, the resistant medium was also supplemented with three BCAAs to screen gene-deficient mutants. The full-length sequences (from its promoter to the 3′-untranslated region) of MrilvC were amplified from the genome, and the product was cloned into pDHt-ben plasmid (conferring resistance against benomyl [Ben]) to obtain the complemented mutant. The disruption mutant was confirmed by PCR and RT-PCR (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The complementary strain for single-copy insertion was verified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using genomic DNA. The primers used for mutants are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for gene disruption

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| MrilvC UF | GGGGACAGCTTTCTTGTACAAAGTGGAATGGACCCGACAGTTAC | For construction of gene disruption plasmid |

| MrilvC UR | GGGGACTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGTTGATGAAAGGGATTGG | |

| MrilvC DF | GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGTTTTGCCGTTCGATTGTT | |

| MrilvC DR | GGGGACAACTTTGTATAATAAAGTTGTGCAGTGCTCCATTCCTA | |

| MrilvC TF | TTCCAGCACCAAGCACCAATA | For verification of gene disruption |

| MrilvC TR | GGCGATGCAGTGCGATGAAG | |

| MrilvC SF | CGTACATCGCTGCCAGAC | For verification of gene disruption and single-copy insertion of complementary strain |

| MrilvC SR | CGTTGAGACCGTTATCCC | |

| MrilvC CF | TACTGCTGGCCAAGCTTCGCTCGCTGATGCCGAGTTTG | For construction of gene complementation plasmid |

| MrilvC CR | GCGGTGGCGGCCGCTCTAGAATCTTAGTCTGCCCGTGT |

Underlined sequences are homologous sequences in plasmid pDHT-Bar or pDHT-Ben.

Fungal vegetative growth and amino acid feeding assays.

A 4-mm-diameter agar plug of each strain from the border of a 5-day-old colony on SDAY plates was centrally attached onto different plates. The diameter of each colony was measured at 14 days. To elucidate the effects of BCAAs auxotrophy on mycelial growth, fungal agar plugs were placed on CZA medium (containing exogenous amino acid[s] at a final concentration of 1 mM) and cultured for 5 days.

Evaluations for conidiation, germination, and penetration.

All strains were grown on SDAY plates for 14 days. Conidia were harvested in 0.05% Tween 80 and filtered through absorbent cotton twice to remove hyphae. For fungal sporulation, 100 μl of 1 × 106 conidial suspension was evenly spread on SDAY or 1/4 SDAY plates, and the conidial yields were assessed as described previously (39). Conidial germination was observed at 36 h postinoculation in liquid medium with shaking. For the penetration assay, conidia were diluted to 1 × 105 conidia/ml using 0.05% Tween 80 or SDY medium, and 3 μl was added on the surface of the wings from cicada. After 3 days, the wings were removed and the remaining SDAY plates were further grown for 3 days.

Cellular stress sensitivity test.

An aliquot of 1 μl of conidial suspension (1 × 107 conidia/ml) was inoculated on PDA medium (BD) with various inhibitors: Congo red at 8 mg/ml, SDS at 0.01%, H2O2 at 5 mM, menadione at 0.01 mM, and NaCl at 1 M. Colony morphology was photographed at 14 days during cultivation.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Fungi were cultured on SDAY plates for 2.5 days, and the mycelia were collected for conidiation-related gene expression analysis. For transcriptional analysis of antioxidant genes, 14-day-old colonies from PDA supplemented with 0.01 mM menadione were used. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were synthesized with ReverTra Ace qPCR RT master mix with the gDNA remover kit (Toyobo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time qPCR analysis was performed using qPCR SYBR green master mix (Vazyme, China). For normalization of gene expression levels, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control. Gene amplification was achieved using the Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, USA). The relative transcription levels of genes in mutants compared to the WT were determined via the 2−ΔΔCT method (40). Primer sequences for qRT-PCR are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

List of genes analyzed by qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward and reverse primer sequences (5′→3′) | Annotation | Homologous gene | E value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAA_06313 | ACTCCAAAGGGCATCACG/CAACAAAGCGGCGGAATA | Developmental regulator (FlbA) | AN5893 (XP_663497.1) | 0 | 41 |

| MAA_04342 | CCGATGAGCGAAGGAGTT/TGTAGAATGCGTAGAAGGGA | Transcriptional activator (FlbC) | AN2421 (XP_660025.1) | 2e−80 | |

| MAA_00122 | TGCGGGTTGAATACGG/CTCCACCTCTTTCTCCTTGA | Developmental activator (FluG) | AN4819 (XP_662423.1) | 2e−54 | |

| MAA_01976 | CACGGCGTCACATAATACA/ACTGAGGACCACCGAAAT | Velvet factor (VelB) | AN0363 (XP_002151265.1) | 7e−50 | |

| MAA_05126 | TCGGTCTGGTTTGCTCTG/GAGGTGCTTCAACAACTTCA | MAP kinase (SakA) | AF282891 | 0 | 42 |

| MAA_00836 | TGCCCAGGGTAATGCCA/GCCACCCTTGCCGAGAT | Superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1) | BBA_02311 (XP_008595630.1) | 6e−101 | 43 |

| MAA_04749 | GGGTAGCTTTGACGAGTT/GGTCCTTGGTAGTCACGA | Superoxide dismutase 2 (Sod2) | BBA_09706 (XP_008603025.1) | 9e−114 | |

| MAA_05433 | TGTCACTCGTGCCAACC/AGCCTTGCGATTCTGGT | Superoxide dismutase 3 (Sod3) | BBA_09382 (XP_008602701.1) | 4e−126 | |

| MAA_03203 | GCAATTCCCGTTGTTCTC/CTGCCCTTCAAAGTGGTG | Catalase 1 (CatA) | BBA_06186 (XP_008599505.1) | 0 | |

| MAA_05879 | TGTGCGAGGTGTTGATT/GTCTGTTGATGGGAAGC | Catalase 2 (CatB) | BBA_05603 (XP_008598922.1) | 0 | |

| MAA_10436 | GATCCCGATTACGTCTA/GTGAGCGAGGTGGCAAA | Catalase 3 (CatC) | BBA_09109 (XP_008602428.1) | 0 | |

| MAA_09564 | TGCCCTGAACACCAACT/CGGTAGCCTTCCACTCG | Catalase 4 (CatD) | BBA_09760 (XP_008603079.1) | 0 | |

| MAA_07675 | GACTGCCCGCATTGAGAAG/AGATGGAGGAGTTGGTGTTG | GAPDH | BBA_05480 (XP_008598799.1) | 0 |

Metabolite separation and intermediate feeding assays.

The yeast extract powder was extracted overnight with 60% methanol (MeOH) at room temperature. After removing precipitate by centrifugation, the supernatant was analyzed by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Agilent 1100) tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS; Agilent 6210 TOFMS) system. A reverse-phase C18 column (250 by 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Phenomenex) was used for separation. Chromatographic conditions were included solvents A (water) and B (MeOH with 0.1% formic acid). Samples were eluted with a linear gradient from 5% to 15% B in the first 20 min, with an increase to 100% B at 25 min, followed by 15 min with 100% B; flow rate, 0.8 ml/min. Mass spectrometry parameters were the same as those of a previous study (44), and the data were acquired in negative mode. The intermediates were obtained according to their retention time by HPLC equipped with an automatic collector (Shimadzu LC-20A) using the same column. Finally, the collected fractions were analyzed by HPLC-HRMS to judge their purity. For feeding of the MrilvC deletion mutant with intermediates, conidia were inoculated in 1 ml of CZA (with three BCAAs) together with a mixture of compound 3 or 4 (at a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml) and cultured at 25°C with shaking for 36 h.

DTX extraction and detection.

The WT and ΔMrilvC mutant strains were grown on SDAY for 14 days, and 100 μl of 1 × 106 conidial suspension was inoculated in SDY medium and grown for 7 days with shaking. The mycelia were filtered, washed, and lyophilized. The dried mycelia then were ground into fine powder, and the homogenized samples (30 mg) were extracted with 1 ml of MeOH by ultrasonication for 30 min and kept at 4°C for 12 h. An Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (100 by 10 mm, 2.7 μm) was used for separation, and the elution conditions included solvents A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). Samples were eluted with a linear gradient from 5% to 100% B in the first 30 min, followed by 15 min with 100% B; flow rate, 0.3 ml/min. Mass spectrometry parameters were the same as those described above, and the data were acquired in positive mode. The DTXs A to F were identified by their high-resolution mass spectra (45). As far as we know, there are no isomers of DTXs A to E (molecular formulas are C29H47N5O7, C30H51N5O7, C30H51N5O8, C30H49N5O9, and C29H47N5O8, respectively), whereas two isomers of DTX F (C29H49N5O8), DTX C2 and desmethyldestruxin C (desmDTX C), are present in the metabolome of Metarhizium (16).

Insect bioassays.

Virulence assays were conducted using wax moth (Galleria mellonella) larvae as the insect host. Topical infection and injection were conducted according to previously described methods (17). The mortality was recorded every 12 h or 24 h after the treatments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31972332 and 31772226) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0200400).

B.H. conceived and designed the study. F.L. and H.Z. wrote the manuscript, conducted the experiments, and analyzed the data. X.Z., X.X., and Y.L. did parts of the experiments. B.H. and F.H. edited the manuscript and supervised the project. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neinast M, Murashige D, Arany Z. 2019. Branched chain amino acids. Annu Rev Physiol 81:139–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee YT, Cui CJ, Chow EW, Pue N, Lonhienne T, Wang JG, Fraser JA, Guddat LW. 2013. Sulfonylureas have antifungal activity and are potent inhibitors of Candida albicans acetohydroxyacid synthase. J Med Chem 56:210–219. doi: 10.1021/jm301501k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreisberg JF, Ong NT, Krishna A, Joseph TL, Wang J, Ong C, Ooi HA, Sung JC, Siew CC, Chang GC, Biot F, Cuccui J, Wren BW, Chan J, Sivalingam SP, Zhang L-H, Verma C, Tan P. 2013. Growth inhibition of pathogenic bacteria by sulfonylurea herbicides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1513–1517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02327-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amorim Franco TM, Blanchard JS. 2017. Bacterial branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis: structures, mechanisms, and drugability. Biochemistry 56:5849–5865. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang CX, Guo FF. 2013. Branched chain amino acids and metabolic regulation. Chin Sci Bull 58:1228–1235. doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-5681-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Y, Hong L, Tang W, Li L, Wang X, Ma H, Wang Z, Zhang H, Zheng X, Zhang Z. 2014. Threonine deaminase MoIlv1 is important for conidiogenesis and pathogenesis in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Fungal Genet Biol 73:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Xu J, Wang J, Ji F, Yin X, Shi J. 2015. Involvement of threonine deaminase FgIlv1 in isoleucine biosynthesis and full virulence in Fusarium graminearum. Curr Genet 61:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s00294-014-0444-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du Y, Zhang H, Hong L, Wang J, Zheng X, Zhang Z. 2013. Acetolactate synthases MoIlv2 and MoIlv6 are required for infection-related morphogenesis in Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Pathol 14:870–884. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Han Q, Xu J, Wang J, Shi J. 2015. Acetohydroxyacid synthase FgIlv2 and FgIlv6 are involved in BCAA biosynthesis, mycelial and conidial morphogenesis, and full virulence in Fusarium graminearum. Sci Rep 5:16315. doi: 10.1038/srep16315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Wang J, Xu J, Shi J. 2014. FgIlv5 is required for branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis and full virulence in Fusarium graminearum. Microbiology 160:692–702. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.075333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Yu M, Jiang H, Xu J, Shi J. 2019. FgIlv3a is crucial in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis, vegetative differentiation, and virulence in Fusarium graminearum. J Microbiol 57:694–703. doi: 10.1007/s12275-019-9123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Han Q, Wang J, Wang X, Xu J, Shi J. 2016. Two FgLEU2 genes with different roles in leucine biosynthesis and infection-related morphogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS One 11:e0165927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang W, Jiang H, Zheng Q, Chen X, Wang R, Yang S, Zhao G, Liu J, Norvienyeku J, Wang Z. 2019. Isopropylmalate isomerase MoLeu1 orchestrates leucine biosynthesis, fungal development, and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacey LA, Frutos R, Kaya H, Vail P. 2001. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: do they have a future? Biol Control 21:230–248. doi: 10.1006/bcon.2001.0938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kepler RM, Humber RA, Bischoff JF, Rehner SA. 2014. Clarification of generic and species boundaries for Metarhizium and related fungi through multigene phylogenetics. Mycologia 106:811–829. doi: 10.3852/13-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu YJ, Luo FF, Li B, Shang YF, Wang CS. 2016. Metabolic conservation and diversification of Metarhizium species correlate with fungal host-specificity. Front Microbiol 7:2020. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie T, Wang YL, Yu DS, Zhang QL, Zhang TT, Wang ZX, Huang B. 2019. MrSVP, a secreted virulence-associated protein, contributes to thermotolerance and virulence of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii. BMC Microbiol 19:25. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1396-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okuda S, Yamada T, Hamajima M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Bork P, Goto S, Kanehisa M. 2008. KEGG Atlas mapping for global analysis of metabolic pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W423–W426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo JA, Guan YJ, Yu JH. 2006. FluG-dependent asexual development in Aspergillus nidulans occurs via derepression. Genetics 172:1535–1544. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donzelli BGG, Krasnoff SB. 2016. Molecular genetics of secondary chemistry in Metarhizium fungi. Adv Genet 94:365–436. doi: 10.1016/bs.adgen.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huarte-Bonnet C, Juarez MP, Pedrini N. 2015. Oxidative stress in entomopathogenic fungi grown on insect-like hydrocarbons. Curr Genet 61:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s00294-014-0452-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westwater C, Balish E, Schofield DA. 2005. Candida albicans-conditioned medium protects yeast cells from oxidative stress: a possible link between quorum sensing and oxidative stress resistance. Eukaryot Cell 4:1654–1661. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.10.1654-1661.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. 2006. Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms through which branched-chain amino acids mediate translational control of protein synthesis. J Nutr 136:227S–231S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.227S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarrold SL, Moore D, Potter U, Charnley AK. 2007. The contribution of surface waxes to pre-penetration growth of an entomopathogenic fungus on host cuticle. Mycol Res 111:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali S, Huang Z, Ren SX. 2010. The role of diamondback moth cuticle surface compounds in pre-penetration growth of the entomopathogen Isaria fumosoroseus. J Basic Microbiol 50:411–419. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonazzi D, Julien JD, Romao M, Seddiki R, Piel M, Boudaoud A, Minc N. 2014. Symmetry breaking in spore germination relies on an interplay between polar cap stability and spore wall mechanics. Dev Cell 28:534–546. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sephton-Clark PC, Voelz K. 2018. Spore germination of pathogenic filamentous fungi. Adv Appl Microbiol 102:117–157. doi: 10.1016/bs.aambs.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meritxell R. 2013. Tip growth in filamentous fungi: a road trip to the apex. Annu Rev Microbiol 67:587–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amiri B, Ibrahim L, Butt T. 1999. Antifeedant properties of destruxins and their potential use with the entomogenous fungus Metarhizium anisopliae for improved control of crucifer pests. Biocontrol Sci Technol 9:487–498. doi: 10.1080/09583159929451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedras MSC, Irina Zaharia L, Ward DE. 2002. The destruxins: synthesis, biosynthesis, biotransformation, and biological activity. Phytochemistry 59:579–596. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortiz Urquiza A, Keyhani NO. 2015. Stress response signaling and virulence: insights from entomopathogenic fungi. Curr Genet 61:239–249. doi: 10.1007/s00294-014-0439-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Zhu J, Ying SH, Feng MG. 2014. Three mitogen-activated protein kinases required for cell wall integrity contribute greatly to biocontrol potential of a fungal entomopathogen. PLoS One 9:e87948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang CS, Hu G, St. Leger RJ. 2005. Differential gene expression by Metarhizium anisopliae growing in root exudate and host (Manduca sexta) cuticle or hemolymph reveals mechanisms of physiological adaptation. Fungal Genet Biol 42:704–718. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fröbius AC, Kanost MR, Gotz P, Vilcinskas A. 2000. Isolation and characterization of novel inducible serine protease inhibitors from larval hemolymph of the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella. Eur J Biochem 267:2046–2053. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson JT. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform 5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang XQ, Feng P, Yin Y, Bushley K, Spatafora JW, Wang CS. 2018. Cyclosporine biosynthesis in Tolypocladium inflatum benefits fungal adaptation to the environment. mBio 9:e01211-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01211-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia YL, Luo FF, Shang YF, Chen P, Lu YZ, Wang CS. 2017. Fungal cordycepin biosynthesis is coupled with the production of the safeguard molecule pentostatin. Cell Chem Biol 24:1479–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang ZX, Jiang YY, Li YD, Feng JY, Huang B. 2019. MrArk1, an actin-regulating kinase gene, is required for endocytosis and involved in sustaining conidiation capacity and virulence in Metarhizium robertsii. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:4859–4868. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-09836-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Vries RP, Riley R, Wiebenga A, Aguilar-Osorio G, Amillis S, Uchima CA, Anderluh G, Asadollahi M, Askin M, Barry K, Battaglia E, Bayram Ö, Benocci T, Braus-Stromeyer SA, Caldana C, Cánovas D, Cerqueira GC, Chen F, Chen W, Choi C, Clum A, Dos Santos RAC, Damásio A. R d L, Diallinas G, Emri T, Fekete E, Flipphi M, Freyberg S, Gallo A, Gournas C, Habgood R, Hainaut M, Harispe ML, Henrissat B, Hildén KS, Hope R, Hossain A, Karabika E, Karaffa L, Karányi Z, Kraševec N, Kuo A, Kusch H, LaButti K, Lagendijk EL, Lapidus A, Levasseur A, Lindquist E, Lipzen A, Logrieco AF, MacCabe A, Mäkelä MR, Malavazi I, Melin P, Meyer V, Mielnichuk N, Miskei M, Molnár ÁP, Mulé G, Ngan CY, Orejas M, Orosz E, Ouedraogo JP, Overkamp KM, Park H-S, Perrone G, Piumi F, Punt PJ, Ram AFJ, Ramón A, Rauscher S, Record E, Riaño-Pachón DM, Robert V, Röhrig J, Ruller R, Salamov A, Salih NS, Samson RA, Sándor E, Sanguinetti M, Schütze T, Sepčić K, Shelest E, Sherlock G, Sophianopoulou V, Squina FM, Sun H, Susca A, Todd RB, Tsang A, Unkles SE, van de Wiele N, van Rossen-Uffink D, Oliveira JVDC, Vesth TC, Visser J, Yu J-H, Zhou M, Andersen MR, Archer DB, Baker SE, Benoit I, Brakhage AA, Braus GH, Fischer R, Frisvad JC, Goldman GH, Houbraken J, Oakley B, Pócsi I, Scazzocchio C, Seiboth B, vanKuyk PA, Wortman J, Dyer PS, Grigoriev IV. 2017. Comparative genomics reveals high biological diversity and specific adaptations in the industrially and medically important fungal genus Aspergillus. Genome Biol 18:28. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1151-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawasaki L, Sánchez O, Shiozaki K, Aguirre J. 2002. SakA MAP kinase is involved in stress signal transduction, sexual development and spore viability in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol 45:1153–1163. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forlani L, Juárez MP, Lavarías S, Pedrini N. 2014. Toxicological and biochemical response of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana after exposure to deltamethrin. Pest Manag Sci 70:751–756. doi: 10.1002/ps.3583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo FF, Wang Q, Yin CL, Ge YL, Hu FL, Huang B, Zhou H, Bao GH, Wang B, Lu RL, Li ZZ. 2015. Differential metabolic responses of Beauveria bassiana cultured in pupae extracts, root exudates and its interactions with insect and plant. J Invertebr Pathol 130:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arroyo Manzanares N, Diana Di Mavungu J, Garrido Jurado I, Arce L, Vanhaecke L, Quesada Moraga E, De Saeger S. 2017. Analytical strategy for determination of known and unknown destruxins using hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem 409:3347–3357. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0276-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.