Scholars (including in this issue of AJPH) have debated which interventions limit the spread of health misinformation on social media, including promoting high-quality information, removing misinformation from platforms, and inoculating people against misinformation by bolstering news, information, and health literacy. Unfortunately, these preventative solutions cannot eliminate health misinformation, necessitating strategies that respond to misinformation to limit its pernicious influence on public attitudes and behaviors.

Corrections—the presentation of information designed to rebut an inaccurate claim or a misperception—are an important treatment for misinformation. Despite the relative stickiness of misinformation, corrections are typically effective in reducing beliefs in health misinformation, although they are less so as issues become more polarized or beliefs become embedded in an individual’s self-concept.1,2

CORRECTION ON SOCIAL MEDIA

On social media, in contrast to individually directed private communication, there are two targets for any corrective message: (1) the person sharing the misinformation, and (2) the community of individuals seeing the misinformation or the correction. These two targets may have different levels of resistance to correction. Someone posting misinformation is likely quite committed to that position, and cognitive dissonance makes it difficult for that poster to alter his or her beliefs after publicly sharing them. However, even people sharing misinformation can be corrected, especially when correction comes from a close tie.3

The second target of a correction on social media is the audience—those who witness a correction on social media but are not directly targeted or engaged in the interaction. This can occur, for example, when individuals see someone who is sharing misinformation being corrected by another user or an expert organization; it could also extend to corrective messages offered in response to commonly held misperceptions without targeting a misinformation post directly. Those watching from afar are likely less affected by cognitive dissonance, as their identity is not directly under threat, and thus more amenable to correction. We refer to this phenomenon as “observational correction.”4,5 Research has consistently documented the ability of observational correction to reduce health misperceptions, including correction from a variety of sources—algorithms within the platform, expert organizations, and other social media users—on different platforms and on a wide range of health topics.4–6

BEST PRACTICES

Research has identified a number of best practices for engaging in observational correction on social media. First, citing highly credible factual information with links to expert sources is important, especially for users offering corrections.1,6 Expert sources themselves are more effective in correcting misinformation than users are, and engaging in such corrections on social media does not appear to negatively affect their credibility.5 Sharing corrections that counter personal or political interest can enhance trust and thus effectiveness, so considering trusted sources among a target audience is essential.

Second, offering a coherent alternative explanation for the misinformation boosts the power of corrections.1,2 Corrections can state what is false and provide an explanation for why it is false (which may include the origins of the misinformation) to have stronger impacts. For example, you could debunk the myth that cutting sugar from your diet will cure cancer by explaining that sugar and diet are linked to cancer risk, but not to its treatment.

Third, multiple corrections reinforce the message, leading to reduced misperceptions.1,5 Repetition is a classic communication strategy and may be necessary when users correct.5

Finally, misinformation should be corrected early, before misperceptions are entrenched.4 Once misperceptions are ingrained and associated with one’s identity, motivated reasoning to protect those beliefs becomes more likely, leading people to dismiss corrective information. Although early corrections may prevent misperceptions from being created, they should avoid drawing attention to uncommon misperceptions and must be transparent about the amount of expert consensus and evidence that exists on a topic.7

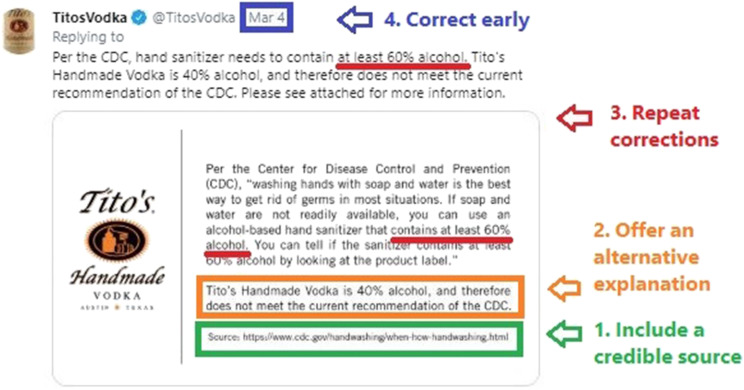

We offer one example of best practices for observational correction in the context of COVID-19 in Figure 1, wherein Tito’s Vodka rapidly responds to an individual claiming she or he used their vodka to make hand sanitizer. The Tito’s Vodka correction includes an unusual source debunking against their self-interest, citing a credible expert in the health domain, explaining why the myth is inaccurate, and repeating the accurate information.

FIGURE 1—

Example of Observational Correction Using Best Practices in the Context of COVID-19

REMAINING QUESTIONS FOR RESEARCH

There is substantial evidence that correcting health misinformation on social media is a fruitful strategy for reducing misperceptions among both those sharing misinformation and the community seeing the interaction. However, more research is needed to determine the efficacy of this strategy and to understand its limits.

First, we must consider the related questions of who engages in correction and how to encourage more people to respond to misinformation. Observational correction depends on a critical mass of trusted, willing, and informed correctors, but in general people are reluctant to confront others on social media and may not be equipped with the skills and information necessary to do so. Research should investigate how to develop appropriate social norms or interventions to encourage corrections on social media. Ideally, corrections would come from across the population, representing different demographics, backgrounds, and attributes; this may require targeted interventions to encourage groups who are currently less likely to engage in corrections. Likewise, relevant experts, professionals, and organizations could be incentivized to engage in corrections.

Second, calculated judgments about which misinformation should be prioritized in correction efforts are needed. If the myth being addressed is sufficiently rare or the account comparatively obscure, efforts to debunk the misinformation may heighten awareness of the myth unnecessarily.1 The potential of the misinformation to cause harm, the vulnerability and size of the audience for the post, and the level of evidence and expert consensus on the issue7 should be part of this calculation, but more research is needed into exactly where correction can do the most good.

Third, false corrections—that is, people claiming to correct when they are actually providing misinformation—merit attention. Not everyone correcting misinformation on social media is doing so accurately or in good faith. Right now, we have little understanding of the effects of false corrections. We also need to know more about how people respond when a correction generates debate about the truth.

Fourth, greater coordination between scholars and social media platforms could make correction more effective. This could include platforms working to highlight the visibility of comments that provide debunking materials; for example, prioritizing comments that link to credible health organizations or trustworthy news media sources. Beyond working with researchers to test interventions, platforms might also make appropriately anonymized data available to researchers, allowing greater investigation into the frequency, scope, and type of misinformation and correction occurring on social media.

Finally, many elements of observational correction may vary by platform or by circumstance. Among these are the tone of the correction, whether the correction comes before or after the misinformation, whether it relies on logic- or fact-based appeals, what sorts of visuals it uses, and what types of popularity or credibility cues are available. Each of these is likely to affect how the corrective information is perceived and whether it is accepted by the audience of users witnessing it.

Health misinformation on social media will not be resolved with any single intervention, but encouraging users, experts, and platforms to correct misinformation as they see it on social media may be part of the solution.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See also Chou and Gaysynsky, p. S270.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewandowsky S, Ecker UKH, Seifert CM, Schwarz N, Cook J. Misinformation and its correction: continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2012;13(3):106–131. doi: 10.1177/1529100612451018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter N, Murphy ST. How to unring the bell: a meta-analytic approach to correction of misinformation. Commun Monogr. 2018;85(3):423–441. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2018.1467564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margolin DB, Hannak A, Weber I. Political fact-checking on Twitter: when do corrections have an effect? Polit Commun. 2018;35(2):196–219. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2017.1334018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bode L, Vraga EK. In related news, that was wrong: the correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media. J Commun. 2015;65(4):619–638. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vraga EK, Bode L. Using expert sources to correct health misinformation in social media. Sci Commun. 2017;39(5):621–645. doi: 10.1177/1075547017731776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vraga EK, Bode L. I do not believe you: how providing a source corrects health misperceptions across social media platforms. Inf Commun Soc. 2018;21(10):1337–1353. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1313883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vraga EK, Bode L. Defining misinformation and understanding its bounded nature: using expertise and evidence for describing misinformation. Polit Commun. 2020;37(1):136–144. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2020.1716500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]