Key Points

Question

Is cigarette smoking associated with changes in specific neurodegenerative biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid?

Findings

In this case-control study of 191 adult men in China, active smoking was associated with at-risk biomarkers for Alzheimer disease, as indicated by higher β-amyloid 42 levels.

Meaning

The results of this study broaden our understanding of the association of cigarette smoking with neurodegenerative disorders.

This case-control study investigates the association of cigarette smoking with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation, oxidation, and neuroprotection.

Abstract

Importance

Cigarette smoking has been associated with risk of neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer disease. The association between smoking and biomarkers of changes in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is not fully understood.

Objective

To investigate the association of cigarette smoking with CSF biomarkers of neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation, oxidation, and neuroprotection.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this case-control study of 191 adult men in China, biomarkers in the CSF of participants with and without significant cigarette exposure were examined. Participants who did not smoke and had no history of substance use disorder or dependence were assigned to the nonsmoking group. The active smoking group included participants who consumed at least 10 cigarettes per day for 1 year. Five-milliliter samples of CSF were obtained from routine lumbar puncture conducted before anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Data collection took place from September 2014 to January 2016, and analysis took place from January to February 2016.

Exposures

Cigarette smoking.

Main Outcomes and Measures

CSF levels of β-amyloid 42 (Aβ42), which has diagnostic specificity for Alzheimer disease, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), total superoxide dismutase (SOD), and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) were measured. Sociodemographic data and history of smoking were obtained.

Results

Of 191 participants, 87 (45.5%) were included in the active smoking group and 104 (54.4%) in the nonsmoking group. Compared with the active smoking group, the nonsmoking group was younger (mean [SD] age, 34.4 [10.5] years vs 29.6 [9.5] years; P = .01), had more education (mean [SD] duration of education, 11.9 [3.1] years vs 13.2 [2.6] years; P = .001), and had lower body mass index (mean [SD], 25.9 [3.6] vs 24.9 [4.0]; P = .005). Comparing the nonsmoking group with the smoking group, mean (SD) CSF levels of Aβ42 (38.0 [25.9] pg/mL vs 52.8 [16.5] pg/mL; P < .001) and TNFα (23.0 [2.5] pg/mL vs 28.0 [2.0] pg/mL; P < .001) were significantly lower, while BDNF (23.1 [3.9] pg/mL vs 13.8 [2.7] pg/mL; P < .001), total SOD (15.7 [2.6] U/L vs 13.9 [2.4] U/L; P < .001), total NOS (28.3 [7.2] U/L vs 14.7 [5.6] U/L; P < .001), inducible NOS (16.0 [5.4] U/L vs 10.3 [2.7] U/L; P < .001), and constitutive NOS (12.4 [6.9] U/mL vs 4.4 [3.9] U/mL) were higher. In addition, in participants in the smoking group who were aged 40 years or older, total SOD levels were negatively correlated with Aβ42 levels (r = −0.57; P = .02). In those who smoked at least 20 cigarettes per day, TNFα levels were positively correlated with Aβ42 levels (r = 0.51; P = .006). The association of TNFα with Aβ42 production was stronger than that of total SOD with Aβ42 production (z = −4.38; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This case-control study found that cigarette smoking was associated with at-risk biomarkers for Alzheimer disease, as indicated by higher Aβ42 levels, excessive oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and impaired neuroprotection found in the CSF of participants in the active smoking group.

Introduction

Evidence from epidemiological studies and meta-analyses have indicated that cigarette smoking is significantly associated with the risk of neurodegenerative disorders,1,2,3 including Alzheimer disease (AD) and dementia. It has been reported that heavy smoking is associated with a greater than 100% increase in risk of dementia and AD after 2 decades of exposure.4 With memory loss and cognitive deficit, AD is among the most devastating brain disorders for older individuals.5 It will affect approximately 100 million people worldwide by 2050.6 Nevertheless, the risk factors and the pathophysiology of AD have not been fully understood.

Cigarette smoking exacerbates amyloid pathology in an animal model of AD.7 The measurement of β-amyloid 42 (Aβ42) levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has diagnostic specificity for AD.8,9,10 Human studies have demonstrated that high CSF Aβ42 levels are strongly associated with AD and mild cognitive impairment due to AD.11 The primary hypothesis for AD development suggests that Aβ42 promotes plaque formation, accompanied with oxidative stress, cortical inflammation, and neuronal loss,12,13 while the abnormal deposition of protein aggregation causes neurotoxicity, cell death, and neurodegeneration.14,15 Furthermore, individuals with mild cognitive impairment showed increased brain oxidative damage before the onset of symptomatic dementia.16 It is understood that the combined effects of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation lead to the accumulation of Aβ,17 and antioxidant supplement application might slow down functional decline in patients with AD.18 Animal models suggest a direct and causal relationship between increased Aβ, reduced superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, and oxidative damage in AD.19 The reaction of nitric oxide and superoxide anion might be responsible for the cellular damage in neurodegenerative disorders, which is a widely accepted explanation of AD.20,21 Nitric oxide is associated with cognitive function,20 and it plays an obligatory role in neuroprotection in the central nervous system (CNS).22 Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) catalyzes nitric oxide formation and accelerates reactions that reduce oxidation. Purified NOS directly catalyzes the generation of oxygen radicals.23 NOS is upregulated in patients with AD, suggesting that these enzymes are instrumental in the pathogenesis of this disease.24 Cigarette smoking has been associated with increased production of reactive oxygen species,25,26 stimulating pro-inflammatory gene transcription and the release of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), which is associated with further increases in Aβ formation.27,28

Increased levels of reactive oxygen species and neuroinflammation are associated with decreases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression.29,30,31,32 Previous studies have suggested that lower concentrations of CSF BDNF are associated with the progression from mild cognitive impairment to AD.33 The neurotrophin BDNF has been shown to protect against future occurrence of dementia and AD and to decrease the risk of dementia in some human studies.34,35,36 Nevertheless, cigarette smoking showed different associations with BDNF levels in human and animal studies.37,38 The present study was conducted to investigate the CSF levels of Aβ42, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neuroprotection in individuals who actively smoke and to further explore the association of cigarette smoking with AD.

Methods

Study Design

This case-control study was conducted following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Inner Mongolian Medical University and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.39 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and no financial compensation was provided to the participants. The cases were defined as individuals who actively smoke, and controls were matched individuals who do not smoke.

Participants

Cigarette smoking is common; however, the association of cigarette smoking with AD is unclear, and it is difficult to collect CSF. Therefore, a sample size of more than 70 participants per group represents a relatively large sample.

Because there are few women who smoke in China,40 very few women were recruited to the active smoking group. Therefore, a total of 191 men in China who were scheduled for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery were recruited from September 2014 to January 2016. Overall, 87 actively smoked, while 104 did not. The active smoking group was further divided into a young subgroup (ie, aged <40 years) and a midlife subgroup (ie, aged ≥40 years), according to the standard diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association. In addition, those with moderate tobacco use (ie, <20 cigarettes/day) were compared with those with heavy tobacco use (≥20 cigarettes/day), according to World Health Organization criteria.

Sociodemographic data, including age and years of education, were collected. Clinical data, such as history of substance use disorders and dependence, were obtained according to self-report and confirmed by next of kin and family members. Patients with a family history of psychosis and neurological diseases or systemic or CNS diseases, determined by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, were excluded.

Participants without a history of any substance use disorder or dependence, including cigarettes, were assigned to nonsmoking group. The active smoking group included participants who consumed at least 10 cigarettes per day for 1 year. Few participants had history of alcohol use disorder, and all participants had no other psychiatric disorders according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition).

Assessments, Biological Sample Collection, and Laboratory Tests

Smoking-related information was obtained from those who actively smoked, including age at smoking onset, years of active smoking, mean number of cigarettes smoked per day, and maximum number of cigarettes smoked per day. Lumbar puncture is part of standard clinical practice for patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstructive surgery. Lumbar puncture was performed in the morning before surgery by a licensed anesthetist, and a 5-mL CSF sample was obtained via intrathecal collection. The time between assessment and lumbar puncture was less than 24 hours. Each CSF sample was then distributed in ten 0.5-mL tubes and immediately frozen at –80 °C for storage.

CSF levels of Aβ42 and BDNF were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals and Cloud-clone, respectively); TNFα, radioimmunoassay kits (DIAsource ImmunoAssays); and total SOD and NOS, spectrophotometric kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). Laboratory technicians were masked to clinical data.

Statistical Analysis

General demographic and clinical data as well as raw biomarker data were compared between groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Analysis of covariance was used for continuous variables to assess the differences between groups. Pearson correlation and partial correlation analysis were performed to test continuous variables and smoking status, adjusted for the covariate of years of education.

We used analysis of covariance to estimate the association of cigarette smoking with each variable, adjusting for age, years of education, and other biomarkers. To explore the association of SOD and TNFα levels with Aβ42 production, partial correlation was performed, adjusted for years of education. To calculate the difference between the 2 r values, Fisher r-to-z exchange was used, based on the literature.41 All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 20.0 (IBM Corp). Figures were created using Prism version 6 (GraphPad) and R version 3.6.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing). All tests were 2-sided, and the significance threshold was set at P < .05.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Of 191 participants, 87 (45.5%) were included in the active smoking group and 104 (54.4%) in the nonsmoking group. Participants in the nonsmoking group were younger (mean [SD] age, 34.4 [10.5] years vs 29.6 [9.5] years; P = .01), had more education (mean [SD] duration of education, 11.9 [3.1] years vs 13.2 [2.6] years; P = .001), and had lower mean (SD) body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (25.9 [3.6] vs 24.9 [4.0]; P = .005), while no differences were found in terms of clinical characteristics between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Groups.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsmoking group (n = 104) | Active smoking group (n = 87) | ||

| Age, y | 29.6 (9.5) | 34.4 (10.5) | .01 |

| Education, y | 13.2 (2.6) | 11.9 (3.1) | .001 |

| BMI | 24.9 (4.0) | 25.9 (3.6) | .005 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 129.8 (12.8) | 127.6 (13.5) | .25 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 75.2 (9.4) | 76.9 (11.6) | .30 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 50.2 (11.6) | 46.3 (11.6) | .36 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 104.2 (27.0) | 104.2 (23.3) | .89 |

| ALT, U/L | 30.0 (22.8) | 31.5 (22.9) | .70 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 181.5 (38.6) | 185.3 (30.9) | .44 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 159.3 (97.3) | 159.3 (115.0) | .28 |

| GGT, U/L | 40.4 (30.8) | 47.3 (45.6) | .43 |

| AST, U/L | 21.5 (9. 4) | 20.6 (7.4) | .66 |

| CSF Aβ42, pg/mL | 38.0 (25.9) | 52.8(16.5) | <.001 |

| CSF BDNF, pg/mL | 23.1 (3.9) | 13.8 (2.7) | <.001 |

| CSF total SOD, U/mL | 15.7 (2.6) | 13.9 (2.4) | <.001 |

| CSF total NOS, U/mL | 28.3 (7.2) | 14.7 (5.6) | <.001 |

| CSF inducible NOS, U/mL | 16.0 (5.4) | 10.3 (2.7) | <.001 |

| CSF constitutive NOS, U/mL | 12.4 (6.9) | 4.4 (3.9) | <.001 |

| CSF TNFα, pg/mL | 23.0 (2.5) | 28.0 (2.0) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: Aβ42, amyloid beta 42; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CSF, cerebral spinal fluid; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

SI conversion factors: To convert ALT, AST, and GGT to microkatals per liter, multiply by 0.0167; BDNF to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1.0; cholesterol, HDL, and LDL to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; and triglycerides to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113.

CSF Biomarkers

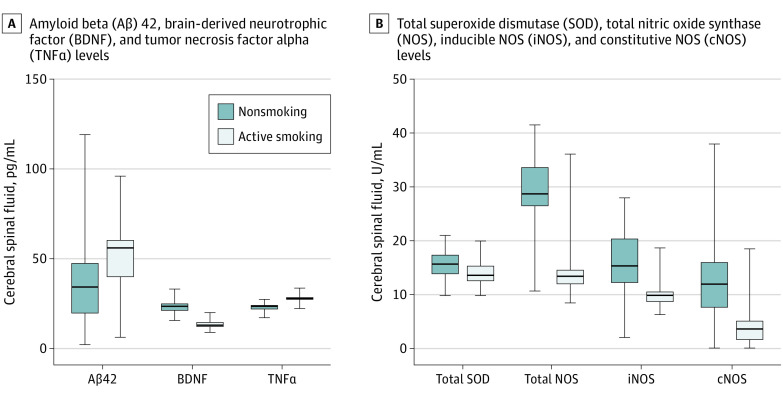

Using analysis of covariance with age, years of education, and other biomarkers as covariates and comparing the nonsmoking group with the active smoking group, mean (SD) CSF levels of TNFα (23.0 [2.5] pg/mL vs 28.0 [2.0] pg/mL; P < .001) and Aβ42 (38.0 [25.9] pg/mL vs 52.8 [16.5] pg/mL; P < .001) were significantly lower in the nonsmoking group. However, BDNF (23.1 [3.9] pg/mL vs 13.8 [2.7] pg/mL; P < .001 [to convert to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1.0]), total SOD (15.7 [2.6] U/L vs 13.9 [2.4] U/L; P < .001), total NOS (28.3 [7.2] U/L vs 14.7 [5.6] U/L; P < .001), inducible NOS (16.0 [5.4] U/L vs 10.3 [2.7] U/L; P < .001), and constitutive NOS levels (12.4 [6.9 U/mL vs 4.4 [3.9] U/mL) were higher in the nonsmoking group (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2. Differences in Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Levels Between Nonsmoking and Active Smoking Group.

| Category | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Dementia related | ||

| Aβ42, pg/mL | –18.5 (–34.4 to –2.6) | .02 |

| Neurotrophin | ||

| BDNF, pg/mL | 9.6 (7.6 to 11.5) | <.001 |

| Oxidation | ||

| Total SOD, U/mL | 2.1 (0.3 to 3.8) | .02 |

| Total NOS, U/mL | 13.1 (8.6 to 17.5) | <.001 |

| Inducible NOS, U/mL | 3.7 (0.7 to 6.8) | .02 |

| Constitutive NOS, U/mL | 11.2 (7.3 to 15.1) | <.001 |

| Neuroinflammation | ||

| TNFα, pg/mL | –4.7 (–6.2 to –3.2) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: Aβ42, β-amyloid 42; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

SI conversion factor: To convert BDNF to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1.0.

Figure 1. Differences in Biomarker Levels in Cerebral Spinal Fluid Between Active Smoking and Nonsmoking Groups.

To convert BDNF to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1.0.

Difference and Correlation in Active Smoking Group

The 87 participants in the active smoking group were divided into young (62 [71.3%]) and midlife (25 [28.7%]) subgroups; 51 (58.6%) were classified as having moderate smoking and 36 (41.4%) as having heavy smoking. There were no differences in CSF levels of BDNF, total SOD, total NOS, inducible NOS, constitutive NOS, and Aβ42 between the young and midlife groups nor between those with moderate and heavy smoking, after adjusting for age, years of education, other biomarkers, and smoking habit (Table 3).

Table 3. Differences in Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Levels Among Subgroups of Active Smoking Group.

| Biomarker | Young vs midlife participantsa | Moderate vs heavy smokingb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | |

| Aβ42, pg/mL | 6.8 (–11.6 to 24.1) | .49 | –1.1 (–15.3 to 13.0) | .87 |

| BDNF, pg/mL | –0.1 (–2.9 to 2.6) | .93 | 0.2 (–1.9 to 2.3) | .87 |

| Total SOD, U/mL | –1.0 (–3.5 to 1.5) | .41 | 0.7 (–1.3 to 2.7) | .50 |

| Total NOS, U/mL | 2.0 (–4.9 to 8.9) | .57 | –0.2 (–5.6 to 5.2) | .94 |

| Inducible NOS, U/mL | 0.9 (–1.7 to 3.6) | .49 | –1.2 (–3.3 to 0.9) | .25 |

| Constitutive NOS, U/mL | –0.2 (–4.2 to 3.9) | .93 | 1.5 (–1.6 to 4.6) | .34 |

| TNFα, pg/mL | 0.6 (–1.5 to 2.7) | .58 | 0.5 (–1.1 to 2.2) | .52 |

Abbreviations: Aβ42, β-amyloid 42; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

SI conversion factor: To convert BDNF to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1.0.

Overall, 62 (71.3%) participants were younger than 40 years and included in the young subgroup, and 25 (28.7%) were included in the midlife subgroup.

Overall, 51 (58.6%) participants smoked fewer than 20 cigarettes a day and were included in the moderate smoking subgroup, and 36 (41.4%) participants were included in the heavy smoking subgroup.

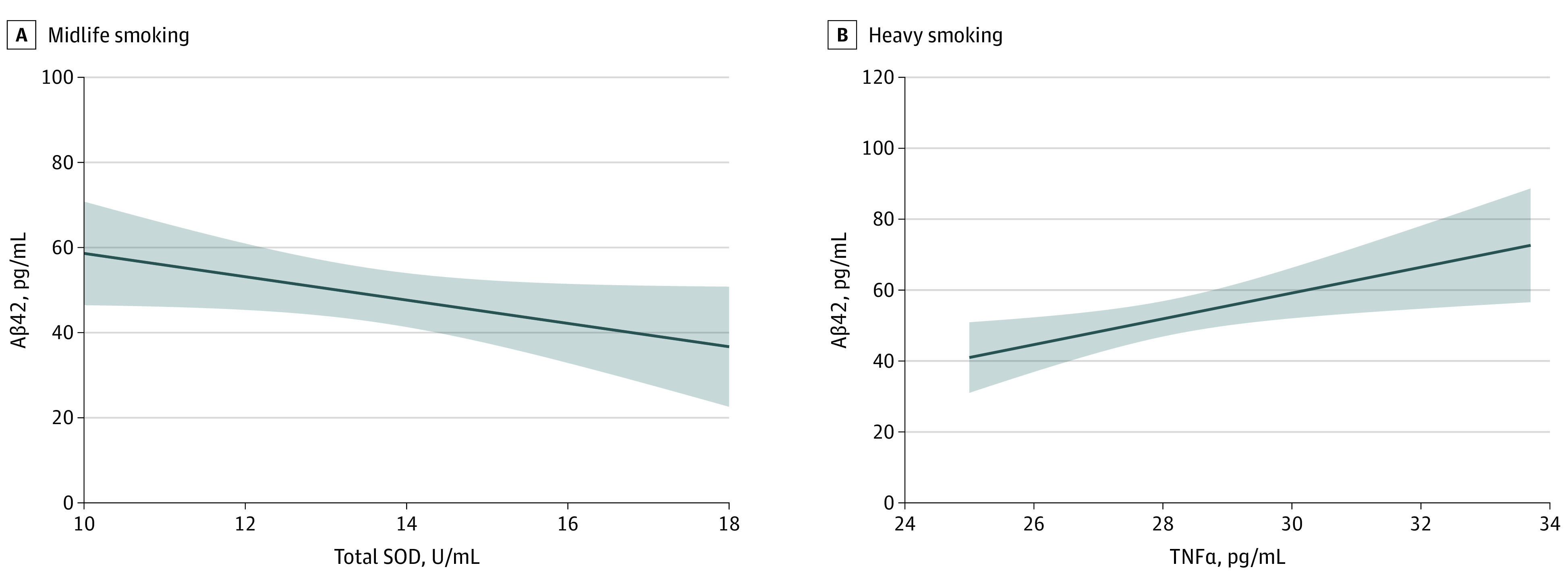

Total SOD levels were negatively correlated with Aβ42 levels (r = −0.57; P = .02) in the midlife group (Figure 2A), and TNFα levels were positively correlated with Aβ42 levels (r = 0.51; P = .006) in those with heavy smoking (Figure 2B), suggesting that the association of TNFα with Aβ42 production was stronger than that of total SOD (z = −4.38; P < .001). There were no significant correlations between AD CSF biomarkers and age at smoking onset, years of cigarettes smoked, mean number of cigarettes smoked per day, and maximum number of cigarettes smoked per day, adjusted for years of education.

Figure 2. Correlation of β-Amyloid 42 (Aβ42) Levels With Total Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) and Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNFα) Levels.

A, The negative correlation of Aβ42 levels with total SOD levels in participants aged 40 years or older who actively smoke (r = −0.57; P = .02). B, The positive correlation of Aβ42 levels with TNFα levels in those who smoke at least 20 cigarettes per day (r = 0.51; P = .006).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first case-control study to investigate the association of cigarette smoking with biomarkers of neurodegeneration, oxidation, and neuroinflammation using CSF. The primary finding was that cigarette smoking was associated with at-risk biomarkers for AD, as shown by higher Aβ42 levels from CSF of participants in the active smoking group. This finding further supports the notion that cigarette smoking is among the risk factors for AD. Rapid changes of CSF Aβ42 levels in older adults with normal cognitive function has indicated the emergence of Aβ42 pathology.42,43 CSF levels of Aβ42 have been shown to have diagnostic accuracy for AD,44 given that changes in these levels are observed years before cognitive decline,45,46,47 allowing for the identification of preclinical AD.48 AD first causes Aβ deposition in the neocortex and later causes tangles in the temporal lobe, sometimes in addition to age-related tangles.49 A large cohort study4 has shown that the risk of dementia and AD is dose-dependent, in that risk increases with the increasing number of cigarettes smoked. Indeed, those with very heavy smoking habits are at the greatest risk of dementia, even decades later in life. Moreover, smoking is a significant risk factor for AD,50 and cigarette smoking increases the severity of some typical abnormalities of AD, including amyloid genesis.7

The secondary findings demonstrated higher levels of total SOD, total NOS, constitutive NOS, and inducible NOS as well as lower levels of TNFα in CSF of participants in the nonsmoking group, indicating neuroinflammation with excessive oxidative stress in participants in the active smoking group. Smoking-related cerebral oxidative stress might serve as a fundamental mechanism contributing to neurobiological abnormalities.51,52,53

Previous research has revealed that the accumulation of some inflammatory toxins from cigarette smoke induces lung injury,54 eg, lipopolysaccharide,55 which not only disrupts the blood-brain barrier56 but also activates microglia.57 The activated classical microglia can further produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators, which elicit toxic effects on neurons and promote tissue inflammation and damage.58 The gas and particulate phases of cigarette smoking have extremely high concentrations of short-lived and long-lived reactive oxygen species and other oxidizing agents, which have been believed to be associated with the etiology of AD.17 In addition to increased free radical concentrations, cigarette smoking is associated with markedly altered mitochondrial respiratory chain function and the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, released by peripheral and CNS glial cells, which collectively promote significant cerebral oxidative stress.1 Cigarette smoking also affects the immune system and augments the production of TNFα,59 which can increase Aβ burden through the upregulation of β-secretase production.27,28 Overproduction of nitrous oxide in the CNS is thought to play a critical role in the pathology of AD.60 Constitutive NOS consists of endothelial NOS and neuronal NOS. Endothelial NOS activity is inhibited by Aβ in basal phosphorylation,61 and neuronal NOS is inhibited by cigarette smoking.62 During CNS inflammation, the increase in endogenous inflammatory cytokine concentration can induce inducible NOS,63 and a rat model of systemic inflammation64 indicated that increased systemic inducible NOS activity can reverse cognitive deficits. Previous studies have reported that chemicals within cigarette smoke reduce the expression of glial inducible NOS.65 In the present study, we found higher TNFα levels but lower total SOD, total NOS, constitutive NOS, and inducible NOS in the CSF of participants in the active smoking group, which indicates that cigarette smoking increases the risk of AD in different ways.

Other findings of the current study included that total SOD levels were negatively correlated with Aβ42 levels in those who were aged 40 years or older and actively smoked. TNFα levels were positively correlated with Aβ42 levels in those who smoked at least 20 cigarettes a day. Aβ impairs mitochondrial function and energy homeostasis in vivo and may directly interact with mitochondria.66 Normally, Aβ decreases as antioxidant concentrations increase.67 In those who smoke, SOD as an antioxidant in vivo is consumed ceaselessly because of overproduction of oxidants. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated age-related increases of oxidative stress68,69 and reported that heavy smoking in midlife was associated with a 100% increase in the risk of dementia and AD.4 These findings strongly support our finding that total SOD levels were negatively correlated with Aβ42 levels in those who smoked and were aged 40 years or older. TNFα has been shown to increase the Aβ burden through suppression of Aβ clearance,28 which provides an explanation for why TNFα levels were positively correlated with the Aβ42 levels in those with heavy smoking. Importantly, using 2 r value comparisons, we found that the association of TNFα with Aβ42 production was stronger than that of total SOD. This comparison provided indirect evidence that pro-inflammatory TNFα exerted more contribution to the at-risk AD pathogenesis than SOD.

Limitations

There were some limitations for the present study. First, CSF cannot directly reflect neuron changes in AD pathology; nevertheless, it represents biochemical changes in the brain. Second, CSF biomarkers measured in this study are considered risk factors for AD instead of biomarkers related to AD pathology with up-to-date knowledge. Third, participants recruited in this study were patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries instead of healthy individuals, which might be seen as a confounder when interpreting the results.

Conclusions

In this study, cigarette smoking was associated with CSF biomarkers of neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation, and oxidation. These are associated with risk of AD.

References

- 1.Durazzo TC, Mattsson N, Weiner MW; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Smoking and increased Alzheimer’s disease risk: a review of potential mechanisms. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3)(suppl):S122-S145. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss BP, Rensel MR, Hersh CM. Wellness and the role of comorbidities in multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):999-1017. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0563-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhan Y, Fang F. Smoking and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a mendelian randomization study. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(4):482-484. doi: 10.1002/ana.25443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rusanen M, Kivipelto M, Quesenberry CP Jr, Zhou J, Whitmer RA. Heavy smoking in midlife and long-term risk of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):333-339. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao C, Zhang H, Li H, et al. Geniposide ameliorates cognitive deficits by attenuating the cholinergic defect and amyloidosis in middle-aged Alzheimer model mice. Neuropharmacology. 2017;116:18-29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(3):186-191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreno-Gonzalez I, Estrada LD, Sanchez-Mejias E, Soto C. Smoking exacerbates amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lautner R, Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Apolipoprotein E genotype and the diagnostic accuracy of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(10):1183-1191. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42, Tau, and P-tau: confirmation now realization. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(12):1552-1553. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, et al. Accuracy of brain amyloid detection in clinical practice using cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42: a cross-validation study against amyloid positron emission tomography. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(10):1282-1289. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(7):673-684. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00070-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353-356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds MR, Singh I, Azad TD, et al. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate Aβ-induced oxidative stress and hypercontractility in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:9. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0073-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(5):362-381. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kametani F, Hasegawa M. Reconsideration of amyloid hypothesis and tau hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:25. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Praticò D, Clark CM, Liun F, Rokach J, Lee VY, Trojanowski JQ. Increase of brain oxidative stress in mild cognitive impairment: a possible predictor of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(6):972-976. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.6.972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Islam MT. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction-linked neurodegenerative disorders. Neurol Res. 2017;39(1):73-82. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2016.1251711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dysken MW, Sano M, Asthana S, et al. Effect of vitamin E and memantine on functional decline in Alzheimer disease: the TEAM-AD VA cooperative randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(1):33-44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuessel K, Schäfer S, Bayer TA, et al. Impaired Cu/Zn-SOD activity contributes to increased oxidative damage in APP transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18(1):89-99. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guix FX, Uribesalgo I, Coma M, Muñoz FJ. The physiology and pathophysiology of nitric oxide in the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76(2):126-152. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(1):315-424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calabrese V, Mancuso C, Calvani M, Rizzarelli E, Butterfield DA, Stella AM. Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(10):766-775. doi: 10.1038/nrn2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SM, Byun JS, Jung YD, Kang IC, Choi SY, Lee KY. The effects of oxygen radicals on the activity of nitric oxide synthase and guanylate cyclase. Exp Mol Med. 1998;30(4):221-226. doi: 10.1038/emm.1998.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asiimwe N, Yeo SG, Kim MS, Jung J, Jeong NY. Nitric oxide: exploring the contextual link with Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:7205747. doi: 10.1155/2016/7205747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernard A, Ku JM, Vlahos R, Miller AA. Cigarette smoke extract exacerbates hyperpermeability of cerebral endothelial cells after oxygen glucose deprivation and reoxygenation. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15573. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51728-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad S, Sajja RK, Kaisar MA, et al. Role of Nrf2 and protective effects of metformin against tobacco smoke-induced cerebrovascular toxicity. Redox Biol. 2017;12:58-69. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao YF, Wang BJ, Cheng HT, Kuo LH, Wolfe MS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and interferon-gamma stimulate gamma-secretase-mediated cleavage of amyloid precursor protein through a JNK-dependent MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):49523-49532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402034200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto M, Kiyota T, Horiba M, et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulate amyloid-beta plaque deposition and beta-secretase expression in Swedish mutant APP transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(2):680-692. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapczinski F, Frey BN, Andreazza AC, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, Cunha AB, Post RM. Increased oxidative stress as a mechanism for decreased BDNF levels in acute manic episodes. Braz J Psychiatry. 2008;30(3):243-245. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462008000300011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Netto MB, de Oliveira Junior AN, Goldim M, et al. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly rats. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;73:661-669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lima Giacobbo B, Doorduin J, Klein HC, Dierckx RAJO, Bromberg E, de Vries EFJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in brain disorders: focus on neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(5):3295-3312. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1283-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calabrese F, Rossetti AC, Racagni G, Gass P, Riva MA, Molteni R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a bridge between inflammation and neuroplasticity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:430. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forlenza OV, Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, et al. Lower cerebrospinal fluid concentration of brain-derived neurotrophic factor predicts progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2015;17(3):326-332. doi: 10.1007/s12017-015-8361-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aisen PS. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor and the risk for dementia. JAMA. 2014;311(16):1684-1685. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laske C, Stransky E, Leyhe T, et al. BDNF serum and CSF concentrations in Alzheimer’s disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus and healthy controls. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(5):387-394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinstein G, Beiser AS, Choi SH, et al. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor and the risk for dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(1):55-61. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamal M, Van der Does W, Elzinga BM, Molendijk ML, Penninx BW. Association between smoking, nicotine dependence, and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism with BDNF concentrations in serum. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(3):323-329. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiaoyu W. The exposure to nicotine affects expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) in neonate rats. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(2):289-295. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1934-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma Y, Wen L, Cui W, et al. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence in men and women residing in two provinces in China. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:254. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diedenhofen B, Musch J. cocor: a comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(3):446-452. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toledo JB, Xie SX, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM. Longitudinal change in CSF Tau and Aβ biomarkers for up to 48 months in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(5):659-670. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1151-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blennow K, Mattsson N, Schöll M, Hansson O, Zetterberg H. Amyloid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36(5):297-309. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, et al. ; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network . Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795-804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):119-128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vos SJ, Xiong C, Visser PJ, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and its outcome: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(10):957-965. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70194-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280-292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mungas D, Tractenberg R, Schneider JA, Crane PK, Bennett DA. A 2-process model for neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(2):301-308. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cataldo JK, Prochaska JJ, Glantz SA. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease: an analysis controlling for tobacco industry affiliation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(2):465-480. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swan GE, Lessov-Schlaggar CN. The effects of tobacco smoke and nicotine on cognition and the brain. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17(3):259-273. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9035-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reitz C, den Heijer T, van Duijn C, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Relation between smoking and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: the Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2007;69(10):998-1005. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271395.29695.9a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyas SL, White LR, Petrovitch H, et al. Mid-life smoking and late-life dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(4):589-596. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00156-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeyaseelan S, Chu HW, Young SK, Worthen GS. Transcriptional profiling of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Infect Immun. 2004;72(12):7247-7256. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7247-7256.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hasday JD, Bascom R, Costa JJ, Fitzgerald T, Dubin W. Bacterial endotoxin is an active component of cigarette smoke. Chest. 1999;115(3):829-835. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Banks WA, Gray AM, Erickson MA, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced blood-brain barrier disruption: roles of cyclooxygenase, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and elements of the neurovascular unit. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:223. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0434-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Durafourt BA, Moore CS, Zammit DA, et al. Comparison of polarization properties of human adult microglia and blood-derived macrophages. Glia. 2012;60(5):717-727. doi: 10.1002/glia.22298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meireles M, Marques C, Norberto S, et al. Anthocyanin effects on microglia M1/M2 phenotype: consequence on neuronal fractalkine expression. Behav Brain Res. 2016;305:223-228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arnson Y, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2010;34(3):J258-J265. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lüth HJ, Münch G, Arendt T. Aberrant expression of NOS isoforms in Alzheimer’s disease is structurally related to nitrotyrosine formation. Brain Res. 2002;953(1-2):135-143. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03280-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toda N, Okamura T. Cerebral blood flow regulation by nitric oxide in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;32(3):569-578. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Toda N, Okamura T. Cigarette smoking impairs nitric oxide-mediated cerebral blood flow increase: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Pharmacol Sci. 2016;131(4):223-232. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao ML, Liu JS, He D, Dickson DW, Lee SC. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression is selectively induced in astrocytes isolated from adult human brain. Brain Res. 1998;813(2):402-405. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01023-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eckel B, Ohl F, Bogdanski R, Kochs EF, Blobner M. Cognitive deficits after systemic induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase: a randomised trial in rats. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28(9):655-663. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283497ce1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mazzio EA, Kolta MG, Reams RR, Soliman KF. Inhibitory effects of cigarette smoke on glial inducible nitric oxide synthase and lack of protective properties against oxidative neurotoxins in vitro. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26(1):49-62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, et al. ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2004;304(5669):448-452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng L, Cedazo-Minguez A, Hallbeck M, Jerhammar F, Marcusson J, Terman A. Intracellular distribution of amyloid beta peptide and its relationship to the lysosomal system. Transl Neurodegener. 2012;1(1):19. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-1-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mutlu-Türkoğlu U, Ilhan E, Oztezcan S, Kuru A, Aykaç-Toker G, Uysal M. Age-related increases in plasma malondialdehyde and protein carbonyl levels and lymphocyte DNA damage in elderly subjects. Clin Biochem. 2003;36(5):397-400. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9120(03)00035-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408(6809):239-247. doi: 10.1038/35041687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]