Abstract

Purpose:

To understand patients’ qualitative experiences with the SEE (Support, Educate, Empower) personalized glaucoma coaching program, provide a richer understanding of the components of the intervention that were useful in eliciting behavior change, and understand how to improve the SEE Program.

Design:

A concurrent mixed-methods process analysis.

Participants:

Thirty-nine patients with a diagnosis of any kind of glaucoma or ocular hypertension who were ≥ age 40, taking ≥ 1 glaucoma medication, spoke English, self-administered their eye drops and had poor glaucoma medication adherence (defined as taking ≤80% of prescribed medication doses assessed via electronic medication adherence monitors) who completed the 7-month SEE Program.

Methods:

All participants who completed the study were interviewed in-person using a semi-structured interview guide after the intervention. Coders conducted qualitative analysis of transcribed interviews using Grounded Theory. Participants were then stratified into groups based on change in adherence, and thematic differences between groups were examined.

Main Outcome Measure:

Themes that emerged from interviews categorized by number of participants who expressed a theme and the number of representative citations.

Results:

Participants expressed positive views toward the program overall (95%, n=37/39). They perceived program components as working together to improve their medication adherence. Interactions with the glaucoma coach (38 participants, 184 citations), motivation to aid personal change (38 participants, 157 citations), personalized glaucoma education (38 participants, 149 citations) and the electronic reminders and hearing their adherence score (37 participants, 90 citations) were most commonly cited by participants as helpful program elements contributing to improved adherence. Patients expressed a desire for personalized education to be a standard part of glaucoma care. Participants who demonstrated more improvement in adherence had a more trusting attitude toward the adherence score and a greater magnitude of perceived personal need to improve adherence.

Conclusions:

Participants reported a highly positive response to the in-person glaucoma education and motivational interviewing intervention used in conjunction with automated adherence reminders.

Precis

In semi-structured interviews after a 7-month glaucoma self-management support program, participants cited interactions with the glaucoma coach most frequently as contributing to improved adherence, followed by personalized education, feedback on adherence percentage and reminders.

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide1. In the United States alone, at least 3 million people will be affected by glaucoma in the year 20202. Though medication has been shown to reduce vision loss,3 nearly half of all glaucoma patients fail to take at least 75% of prescribed doses.4 Patients often do not refill a second prescription,5 schedule a follow-up visit,6 or maintain adherence to treatment over time.7,8 This poor adherence is associated with disease progression.9,10 Interventions to improve adherence must be leveraged to improve patient outcomes.

As pressure to reduce the cost of medical care grows,11 the delivery of healthcare through technology, or eHealth, has gained popularity as a cost-effective, efficient solution because it does not require health care provider time.12 However, technology-mediated educational interventions alone have thus far had limited effectiveness in improving medication adherence.13 For glaucoma patients, interventions that included only educational materials did not improve adherence,14,15 even when web-based and personalized.16

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a patient-centered counseling technique used to facilitate positive health behavior change. It has been successful in changing health behaviors in a wide range of conditions ranging from tobacco abuse to diabetes to poor medication adherence among the elderly.17 MI is defined as “a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change.”18 MI is consistent with the principles of Self Determination Theory (SDT), which asserts that positive health behaviors are enhanced in an environment that supports autonomy and confidence.19,20 MI works through SDT to lay the groundwork of support for patient-motivated change. To this end, we created the Support, Educate, Empower (SEE) personalized glaucoma coaching program for patients with poor adherence. In the seven-month SEE Program, health educator, social worker or ophthalmic technicians trained as glaucoma coaches used an eHealth tool to deliver personalized education (e.g. based on each person’s diagnosis, test results, physician’s recommendations) and MI-based counseling to guide patients to identify their barriers to optimal adherence and brainstorm solutions collaboratively.21

In the SEE Program pilot study, we collected both quantitative outcome data (electronically monitored medication adherence before and during program participation) and qualitative process data (interviews after SEE Program participation). Qualitative data provides essential insights into patient perspectives.22 Consistent with our patient-centered approach, we used the qualitative data collected in semi-structured interviews after SEE Program participation to: 1) understand patients’ experience with the SEE Program; 2) provide a richer understanding of the components of the intervention that were useful in eliciting behavior change; and 3) understand how to improve the SEE Program.

Methods

Study population

Patients at the University of Michigan Health System with a diagnosis of glaucoma, glaucoma suspect or ocular hypertension, age ≥ 40, taking ≥ 1 glaucoma medication were included in recruitment between December 2016 and August 2018. Those who had cognitive impairment or severe mental illness (defined as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or a major depressive episode with psychotic features), did not speak English or opted out of recruitment were excluded. Patients who did not opt out were called and asked to assess their glaucoma medication adherence via self-report through two validated questionnaires: an 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale adapted for glaucoma23,24 and the Chang adherence scale.25 as well as a pre-screening questionnaire verifying exclusion and inclusion criteria. Those self-reporting poor adherence (defined as a score ≤6 on the Morisky scale and <95% on the Chang scale) and who instilled their own eye drops were invited to participate in the study. The first phase of the study consisted of an eligibility assessment period during which medication adherence was monitored electronically for three months. Those whose adherence was ≤80% were included in the SEE Program pilot study.

Adherence monitoring

Participants stored each of their glaucoma medications in individual AdhereTech electronic medication monitors, which look like large pill bottles (AdhereTech, New York, USA).21 A date and time stamp were recorded when participants opened monitors to access their medications. When a participant opened the monitor within a specified time window (dependent on the participants’ prescribed dose schedule), this counted as an adherence event.21 Adherence scores were calculated by taking the total number of doses of an individual medication over a specific time frame, divided by the total number of doses of that medication prescribed. Participants prescribed more than one medication received a score representing their average adherence score for all of their medications. Adherence improvement was defined as the difference in mean adherence score between the three-month baseline period and the seven-month program period. Outcomes on adherence are reported elsewhere; here we use change in adherence rates at posttest to stratify the sample into level of response.

SEE Program

The SEE Program has been described in detail previously.21 In brief, participants attended an initial visit to turn on medication alerts and reminders followed by three in-person visits conducted by a glaucoma coach to deliver personally tailored education about the person’s disease, doctor’s treatment recommendations and barriers to optimal self-care outside of regularly-scheduled glaucoma care appointments over 7 months. The glaucoma coach followed up with participants over the phone five times between the in-person sessions to share the participant’s adherence score, check in about their action plan for improving adherence, and troubleshoot any issues that may have arisen. In-person and phone MI-based counseling sessions totaled approximately 130 min for each participant. All participants received information about how to call the glaucoma coach if they needed help, how to access the personalized educational materials online and they received a printed copy of their action plan at the end of each in-person session. The three glaucoma coaches were an ophthalmic technician, a social worker and a health educator (three total coaches) trained through an 16 h glaucoma-specific MI training program.26

Participant feedback

Semi-structured in-person exit interviews were conducted at the conclusion of the active portion of the SEE Program among all 39 participants who completed the intervention. A research assistant conducted the semi-structured interviews using an interview guide with 12 open-ended questions that took approximately 30 minutes in total (Supplement 1). These questions elicited information regarding each participant’s thoughts regarding SEE content, interactions with the glaucoma coach, logistical preferences, and overall feedback. Five closed-ended questions assessing: (1) preference for in-person sessions vs. phone calls, (2) if participants would have preferred SEE appointments to be scheduled in combination with regular glaucoma care, (3) if participants referred to their printed copy of the adherence plan developed with the counselor outside of sessions, (4) if participants visited the on-line educational materials outside of sessions, and (5) if participants called the glaucoma coach outside of scheduled sessions. Not all participants were asked all of the closed ended questions because these questions were added to the interview guide in an iterative fashion; when a participant brought up an important element of feedback, we subsequently incorporated it into the interview guide to ask the rest of the participants. Interview sessions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Qualitative analysis

Analysis followed a concurrent mixed-methods approach.27 Qualitative analysis of transcribed interviews was guided by Grounded Theory (GT), an inductive process of generating theories, beginning with qualitative data.28–30 Coders followed a stepwise approach typical of GT:31,32 (1) familiarization, (2) open coding, (3) axial coding, (4) focused coding, and (5) theory building. Once transcripts had been coded, they were stratified into groups based on amount of adherence change and re-analyzed for qualitative differences between groups.

Three coders read interview transcripts during the familiarization stage, aiming to become familiar with the context and general interview topics. Coders determined that thematic saturation, the point at which additional interviews provided no new themes, was reached after reading ten interviews.33 Open coding involved identification of reoccurring concepts from ten semi-structured interviews. Instances of these concepts were identified and subsequently, during axial coding, relationships between these concepts were considered. Twelve core concepts encompassing related concepts were discussed and identified during focused coding. Two coders then worked separately to organize sections of all transcripts into these concepts, coming together to resolve inconsistencies in coding and develop sub-categories (PM, VE). A third party (PANC) was included where inconsistencies could not be resolved between coders. Coders engaged in memo writing throughout all stages, creating written records of their thought processes to track thought processes toward informing hypotheses. The transcripts were coded and analyzed using standard content analysis methods with Nvivo 12.0 (QRS International Pty Ltd., Victoria, Australia) software.

Finally, theory building involved a review of coders’ memos, as well as subcategorization of coded data. This allowed development of theories by comparing hypotheses generated throughout coding. After coding, interview transcripts were stratified into four groups, based on the participants’ adherence improvement. These groups were: Adherence Declined (relative change in adherence < 0%), No Improvement (relative increase in adherence < 5%), Slight Improvement (5% < relative increase in adherence < 20%), Considerable Improvement (relative increase in adherence > 20%). Differences in theme prevalence between these subgroups were examined, and a joint display was created (CH) Fisher’s exact tests and Kruskal Wallis tests were conducted to identify demographic differences between groups.

Consent and permissions

Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM00112614). The trial adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Eligible participants were assessed for willingness to participate in the study. Written informed consent was obtained at the first study visit. The trial was registered at Clinical-Trials.gov (ID #NCT03159247).

Results

Study sample

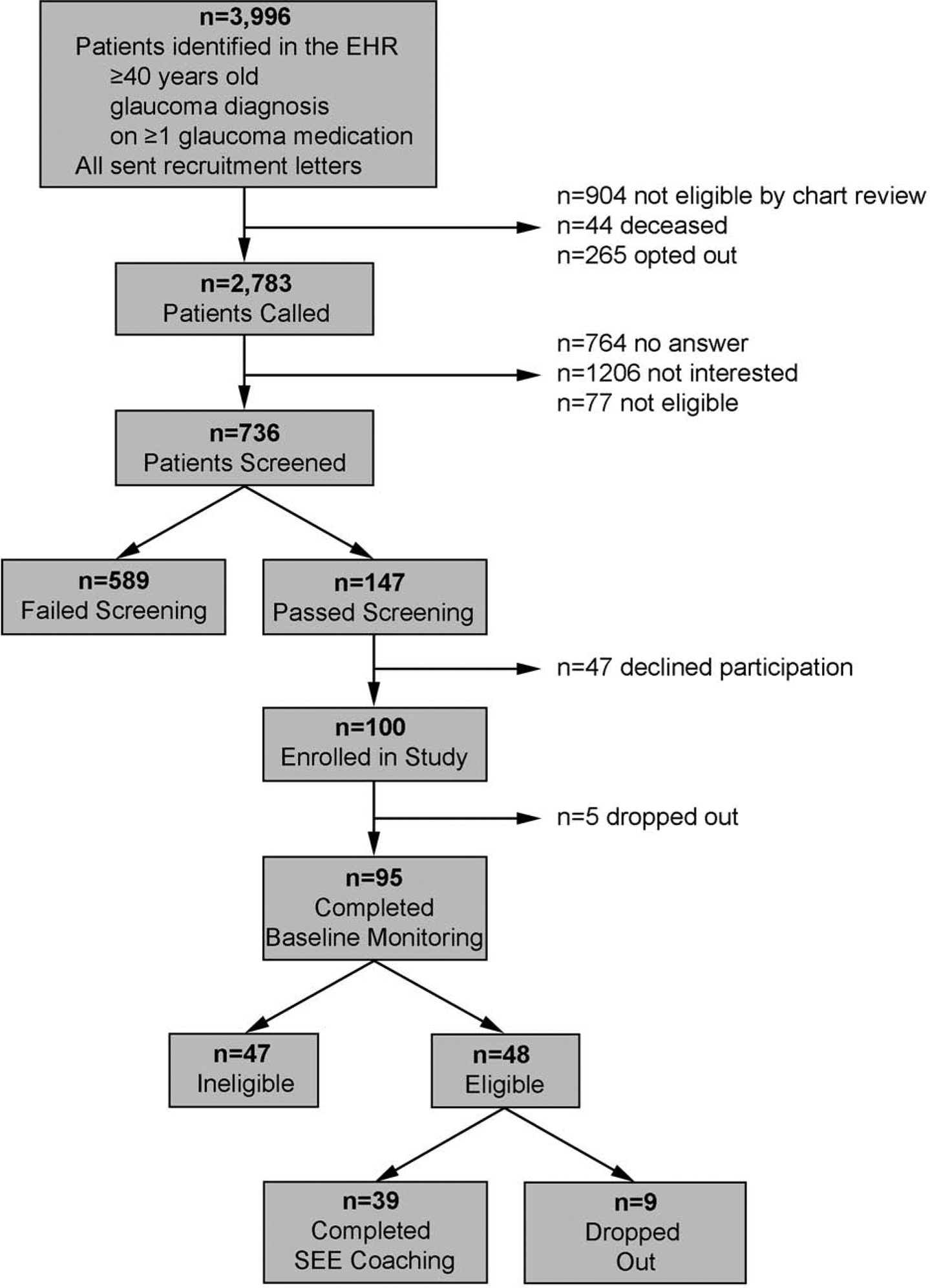

One hundred patients met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the baseline study visit (Figure1). After the baseline study visit, medication adherence was monitored electronically for three months and those whose median adherence score was ≤80% were eligible to participate in the SEE Program pilot study. Ninety-five participants completed the three months of baseline adherence monitoring and 48 were eligible to participate in the SEE Program pilot study. Of the 48 eligible participants, 39 completed the program (18.8% attrition rate) and participated in the semi-structured interviews. (Figure 1) Participants’ mean baseline adherence score was 59.9% (standard deviation, SD = 18.5%), and mean intervention adherence was 81.3% (SD = 17.6%). Further demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Participant Recruitment and Participation (CONSORT Diagram) EHR, Electronic Health Record; SEE, Support Educate Empower

Table 1.

Study sample demographics, overall and by group (n=39 completed and eligible)

| Total (n=39) | Adherence Declined (n=1) | No Improvement (n=6) | Slight Improvement (n=11) | Considerable Improvement (n=21) | P-value* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical Variable | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Education (n=39) | |||||||||||

| <HS or HS | 8 | 20.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 16.7 | 3 | 27.3 | 4 | 19.1 | 0.9 |

| Some College | 12 | 30.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 16.7 | 4 | 36.4 | 7 | 33.3 | |

| College Degree | 8 | 20.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 16.7 | 2 | 18.2 | 5 | 23.8 | |

| Degree | 11 | 28.2 | 1 | 100.0 | 3 | 50.0 | 2 | 18.2 | 5 | 23.8 | |

| Race (n=38) | |||||||||||

| White | 16 | 42.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 50.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 7 | 33.3 | 0.6 |

| Black | 18 | 47.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 50.0 | 3 | 30.0 | 12 | 57.1 | |

| Other | 4 | 10.5 | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 9.5 | |

| Ethnicity (n=32) | |||||||||||

| Hispanic | 1 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.9 | 1.0000 |

| Non-Hispanic | 31 | 96.9 | 1 | 100.0 | 5 | 100.0 | 9 | 100.0 | 16 | 94.1 | |

| Insurance (n=39) | |||||||||||

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.0000 |

| Yes | 39 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 6 | 100.0 | 11 | 100.0 | 21 | 100.0 | |

| Income (n=34) | |||||||||||

| <$25k | 8 | 23.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 3 | 27.3 | 4 | 23.5 | 0.2 |

| $25–$50k | 14 | 41.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 36.4 | 10 | 58.8 | |

| $51–$100k | 7 | 20.6 | 1 | 100.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 2 | 18.2 | 2 | 11.8 | |

| >$100k | 5 | 14.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 2 | 18.2 | 1 | 5.9 | |

| Sex (n=39) | |||||||||||

| Female | 17 | 43.6 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 16.7 | 3 | 27.3 | 12 | 57.1 | 0.1 |

| Male | 22 | 56.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 83.3 | 8 | 72.7 | 9 | 42.9 | |

| Continuous Variable | Mean (SD) | Min, Max | Mean (SD) | Min, Max | Mean (SD) | Min, Max | Mean (SD) | Min, Max | Mean (SD) | Min, Max | P-value** |

| Age (n=39) | 63.4 (10.7) | 41.0, 82.0 | 56.0 (.) | 56.0, 56.0 | 67.0 (9.0) | 52.0, 77.0 | 63.0 (7.9) | 51.0, 74.0 | 63.0 (12.6) | 41.0, 82.0 | 0.7 |

| Baseline Adherence (n=39) | 0.60 (0.18) | 0.13, 0.80 | 0.74 (.) | 0.74, 0.74 | 0.65 (0.25) | 0.13, 0.79 | 0.63 (0.19) | 0.13, 0.80 | 0.56 (0.16) | 0.13, 0.73 | 0.04 |

Fisher’s exact test (excluding category “Adherence Declined” where n=1)

Kruskal Wallis test (excluding category “Adherence Declined” where n=1)

HS, High School; SD, Standard Deviation

Overall attitudes toward the program

When initially queried about experiences with the program as a whole (Supplement 1), nearly all (95%, 37/39) participants expressed positive feelings by using an adjective with positive valence or describing something they gained from the program, most commonly knowledge gained regarding glaucoma and how the program changed their perspective. “It was predominantly a learning experience more than anything else. I didn’t really have a good understanding of glaucoma, nor the seriousness of it or what the end result could be. So it was very much an eye opener for me,” one participant said. Two participants responded neutrally, with factual information about the program.

Participant-perceived program elements aiding adherence

Interactions with the glaucoma coach (38 participants, 184 citations), motivation to aid personal change (38 participants, 157 citations), personalized glaucoma education (38 participants, 149 citations) and the electronic reminders and hearing the adherence score (37 participants, 90 citations) were most commonly cited by participants as the most helpful program elements contributing to improved adherence. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Core concepts coded throughout interview transcripts (n=39)

| Core concept | Subcategory [number of participants who discussed, number of citations] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers (to adherence and program participation) | No barriers to participation [25; 42] | Challenges during the program [26; 51] | Barriers to adherence [24;56] | ||||

| [Discussed by 39 participants; 185 individual thoughts] | “I really didn’t have any [barriers] […] I come here the same day I have a doctor appointment. […] And she’d let me know ahead of time how long the visit is going to be, [and ask] if I want to do it the same day or a different day of my doctor’s appointment.” | “It was also confusing

because the clinic taught us one thing and the doctors talked something

else. So the clinics stress the timing of the bottle […] and the

doctors taught taking the drops before

bedtime.” “Difficult may be is too strong a word [.It was] a little annoying to have […] to drive all the way in.” |

“I knew nothing about it. I

didn’t even know I had it. It was instant, still when I had eye

[indiscernible] [00:09:41] doctor. So it’s that’s - I

learned a lot because it’s not something that’s been

advertised like everybody would talk about hypertensions and diabetes

and all cancer. Very few people will talk about glaucoma. I

didn’t know that thing.” “Yeah I mean I always take a long walk and so it would be an hour or an hour and a half before I would get back and take the meds or you know the drops.” “Sometimes I remember, ‘Oh yeah I haven’t done it yet,’ but in the moment I could be in the bathroom, or I’m away from my bottle and I could not do it. And by the time I have, I’ve forgotten about it.” |

||||

| Attitudes | Positive [33; 103] | Negative [9;16] | |||||

| [39 participants; 156 thoughts] | “It was predominantly a

learning experience more than anything else. I didn’t really have

a good understanding of glaucoma nor the seriousness of it or what the

end result could be. So it was very much an eye opener for

me.” “[The program] gave me more knowledge care of myself.” knowledge about my glaucoma and it puts me on a better footing and how to ta |

“My feeling I think eventually became that that was not really all that necessary for me. I’m not sure that was her goal so we had maybe a difference of opinion, but she didn’t really or I didn’t feel forced into it you know. You know I’m dealing with somebody who doesn’t agree with me all the time.” | |||||

| Objective measures | Adherence score [38; 65] | Intraocular pressure [11; 14] | |||||

| [39 participants; 86 thoughts] | “When I got better to 80 percent, that

was helpful because it’s like, ‘Okay, I’m getting

better;’ and then to get a 100 is like ‘Okay, yeah,

I’m getting it.” “Mostly I thought I was doing better than I was. So it is another motivation thing to see it. It’s kind of a competitive thing too like I’m only doing 87%, that’s not good, I need to do more. And then the next time when it will be higher, I will be like woohoo. […] Really for me it was motivation and thinking about why […] the numbers were the way they were.” |

“I do whatever I can to keep the pressures low whatever happens it’s going to happen you know. I’m worried about my eyes 10 years from now and I could be run over by a truck on my way to my car.“ | |||||

| Counselor | |||||||

| [38 participants; 184 thoughts] | “It sticks with you when

somebody can help you and you can understand what she’s talking

about and now it kind of gets into your head.” “She had alternates, [the counselor]. When I said, ‘[counselor’s name], when I tried that, it didn’t really work.’ She would always have an alternate for me to try.” “She answered a lot of questions that I didn’t think was even a question, so we just started talking about glaucoma and the things that I found out are more about glaucoma.” “When I come here, you know when you come to someone and someone makes you feel valuable it really helps you a lot and so she may come here, she would make me feel at home.” “It wasn’t a strict doctor-patient relationship. It was comfortable. It was, she wasn’t overbearing, telling we do it like this, we find these things were better form. It was on me. It was my decisions.” “She’s one of those educators that doesn’t make you feel like an idiot because you don’t know it…” “The very first time I met her when I came in. She did everything she could to make me feel comfortable, to very much go over what the objectives and the goal of the thing, of this program was. And we’ve had, you know, some personal dialogue around, you know, personally what’s going on with, personally what was going on with her. And for her to open herself up to a stranger like that was a powerful.” “Having [the counselor] around meant a little more time to take a doctor’s statement and kind of expound on it.” |

||||||

| Personal Change | |||||||

| [38 participants; 157 thoughts] | “When I was first

diagnosed, it just didn’t – there was no click in my head.

[…] Throughout the study, I’ve really come to understand

this is something I can take ownership in and how I can take care of

myself […] This was all information provided to me during my

visits to the doctors. But it just in this context – it clicked

so much better.” “I’m more aware now than I was before. Before it was sort of like it’s something that you do it whatever. And I may not have been doing that and just because it didn’t have the – how should I say the same before so now, that’s one of the things that I think about, you know. I really think that as people aged, things like taking medications or whatever becomes sort of a – they run the black burn or you’re just trying to get through today or whatever.” “Sometimes I just didn’t feel like doing it until I got into the program and we started talking about the importance of doing it and seeing the video and seeing what [can happen] […] It helped a lot [to see] what I need to do if I wanted keep the vision that I have in my eye.” “The study really, really changed it helped me develop those skills to like take my drops because prior to the study, I would forget my drops 99% of the time. […] Afterwards, I feel like I never forget.” |

||||||

| Education | |||||||

| [38 participants; 149 thoughts] | “I never knew the severity

of glaucoma that I don’t know how I got it or where it came from,

but I do know that the sight I’ve lost, I can’t get back.

And to continue to have sight, I must follow a regimen of taking care of

my eyes. So, the eye study has been like a total reminder to me, which

was very good.” “When I come in for my eye checkups, they really don’t go into glaucoma. They just look at the pressure in my eyes and dilate them and run their tests but they don’t give you a lot of other information.” “I really felt like doctor was making something up. And if it was all presented with that initial diagnosis as part of the office visit, it would be most helpful. […] ‘I’m giving you this material and then here, […] you might want to take this home, study it further, come to an understanding of it, and then maybe, how’s it going on the phone’.” “When you sit an old guy down like me and say you got glaucoma or, you know, your pressure is getting greater, slap that video in front of me or have at some later day, you know, to come for glaucoma orientation […] When I first learned about the glaucoma it would have been great to say, you know, I’m going to go ahead and sit with [the counselor] for a minute. She’s going to […] fill in the blanks for you, the questions you have.” |

||||||

| Bottles and reminders | Positive [28; 47] | Negative [4; 6] | |||||

| [37 participants; 90 thoughts] | “The bottles really help

because they blink and then I got reminders and texts and all that stuff

so like it helped and, you know, now it’s like 7 o’clock,

9 o’clock to take my medicine because if not these lights are

going to blink.” “I think having those battles on the bathroom counter [was the most helpful part of the program], you know, because they’re bigger than the bottles and then they were protected. They weren’t just on the floor so I would see them every day.” “I used to use my phone before, but sometimes you never check - you would never have your phone on you.” “At first, I found the bottle and the light and the alarm to be just annoying as can be. But my compliance was way down then. I’m not even sure I was hitting 75%, so it was getting me into the habit of using my eye drops, I found very intrusive. But it was something that I absolutely needed to do and I wasn’t doing.” |

“I told her I am going to go on vacation, so I am not taking the bottles because it takes up too much space but […] they are just big. […] When you are packing a suitcase, it’s like I don’t want to deal with.” | |||||

| Phone calls | |||||||

| [37 participants; 64 thoughts] | “Sure, [the phone calls were helpful]. I mean, they were both easy to talk to when we have the phone calls. It was useful to make contact and see how it was going. To see if I was following through on my – on the suggestions we agreed on.” | ||||||

| Eye drop instillation | |||||||

| [33 participants; 96 thoughts] | “I used to put it on my

eyelid and then take it but Lori showed me all the stuff that you

don’t have to do that, you can just take, you know, take it and

just let’s put it on your hands and let it drop without your eyes

drop touching your lids. So that nice.” “She helped me put my eye drops in, and I was doing those and made suggestions how she thinks and you know that would be easier for me, there’s a way for me to do it or it felt good.” “I would carry the bottle in my pocket so if I’m not around this I can still take.” “I wasn’t ever sure whether, you know, how much was coming out of the bottle and she said well, you know, you might try to let using the eye drops when you’re lying down. So, you know, we are trying that – we talked about whether that worked.” |

||||||

| Suggestions | |||||||

| [28 participants; 53 thoughts] | “[The program should include] more about how people progress with glaucoma. […] I don’t know that you could really do that because I would love to know what I’m I going to be like in five years or 10 years.” | ||||||

| Social support | Positive [16; 22] | Neutral [6; 6] | Negative [4;4] | ||||

| [25 participants; 32 thoughts] | “My wife would say, who’s texting you. Oh my bottle is reminding me that I have – I showed it to a lot of my friends too.” | “Unfortunately, I don’t have any close family that’s still living. So, there’s not a lot for me to involve. […] If I had a significant other, I program].” would like to bring them in just so they can see what’s going on.” | “My wife knew I didn’t take [my drops] a long time and she was critical of that. […] So, she didn’t need to be involved with the details [of the | ||||

| Fear | |||||||

| [24 participants; 42 thoughts] | “She showed me a video of

how you lose your peripheral vision. And I never knew that. It scared me

to death because I’m the only driver in the

house.” “Now, I see what went wrong with some of the pictures and videos that I have seen on the program. I can see more of [what] happens. [You] start losing sections in your eyesight, not noticing things. So I [am] more […] anxious and I want to make sure that I keep taking the [drops].” “When I was presented with the photos and the video and realized how much worse it could get it could [get] if I don’t [do] something about it, so my motivation of controlling it or at least complying with medication is lot stronger.” |

||||||

Relationship with the glaucoma coach and motivation to aid change

Most participants mentioned at least one interaction with the glaucoma coach that they felt contributed to improving their adherence. Participants referred to the glaucoma coach as a “friend,” “accountability partner,” and “second mom,” among other descriptors. The glaucoma coach’s rapport and non-judgmental responses were discussed frequently as important in allowing participants to be honest about their struggles with adherence and eye care-related questions. “It wasn’t a strict doctor-patient relationship. It was comfortable. […] She wasn’t overbearing, telling me to do it like this. […] It was on me. It was my decisions.” (Table 2)

Participants identified multiple aspects of their interactions with the glaucoma coach as helpful including education through conversation, brainstorming solutions to adherence barriers, and follow-up phone calls. “She also wouldn’t let you get away with it just to see it one time. She’d phone and she’d talk to you […] until the next session,” one participant recalled. The majority of participants stated that they utilized solutions developed in partnership with the glaucoma coach addressing their adherence barriers, such as forgetting to administer eye drops during the day.

Participants also explained how the interactions with the glaucoma coach aided in their motivation to improve their glaucoma medication taking behavior. “When I was first diagnosed, it just didn’t - there was no click in my head. […] Throughout the study, I’ve really come to understand this is something I can take ownership in and how I can take care of myself […] This was all information provided to me during my visits to the doctors. But it just in this context - it clicked so much better.” (Table 2)

Thirty-seven (of 39) participants found phones calls with the glaucoma coach helpful while two did not say anything distinctly positive. For many they served as a reminder to keep medication adherence in mind and provided space to troubleshoot adherence strategies and ask questions. Many went on to talk about how helpful it was to have an on-going conversation in-person and over the phone about the different strategies they were using to improve their adherence. “Because you got the basic information […] and you put me on road. Now I had to follow the road and if there was a decision to make, either I did it on my own or I did it and before I got too far down the road I come in and seen one of you and, ‘Hey that’s not a good idea I want to do it this way,’ so then I’ll modify my plan.” (Table 2)

Given how helpful participants found the phone calls, we queried 35 participants about whether they would prefer having all of the visits as phone visits rather than in-person sessions with the glaucoma coach. Most participants (74%, 26 out of 35 queried) stated that they preferred in-person counseling (Table 3). “I don’t think I would have made the effort on the phone call to get my computer […] loaded up and everything [to view the on-line material]. […The video] was really so impactful for me […so the program] would have […] been less successful.” Four of the participants went on to comment on the importance of an initial in-person session, with one stating, “Especially in the beginning [in-person is great] when you’re trying to establish a relationship.”

Table 3.

Closed-ended question responses*

| Question | Yes | No | Ambivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preference for some in-person counseling visits | 26 | 2 | 7 |

| Preference for counseling sessions in conjunction with routine glaucoma care | 8 | 12 | 10 |

| Recalled receiving the plan page | 31 | 3 | |

| Referred to the printed plan page outside of sessions | 10 | 24 | |

| Visited eyeGuide website outside of sessions | 8 | 28 | |

| Called the counselor outside of sessions | 16 | 14 |

N does not add up to 39 in each case as not all participants were asked all closed ended questions

Sixteen participants discussed calling the glaucoma coach outside of regularly-scheduled sessions, often to discuss new barriers to adherence (Table 3). Others mentioned that they did not feel the need to call the glaucoma coach because they could wait until the next session if a question arose. “I was comfortable with the information and knew I was going to get to see her again,” said one participant. Twelve participants cited specific examples of how the glaucoma coach acted as a healthcare navigator in helping resolve concerns with pharmacies or clinic. For example, one participant noted that having the glaucoma coach’s help “[g]etting the prescriptions worked out and facilitating appointments with the eye doctor [was the biggest contributor to my improvement in adherence].”

Time also arose as an often-discussed factor in participant conceptualization of the program and the glaucoma coach’s role. Seven of 39 participants cited specific examples of how education from the glaucoma coach felt less rushed or more comprehensive than that from their physician, stating that this bolstered their ability to understand their diagnosis. “I always felt that she was a good sounding partner. You know you always can’t talk to your doctor because they are just too busy […] it was really nice to have that support.” Similarly, nine participants said that the ease of re-scheduling appointments prevented scheduling from becoming burdensome in participating in the SEE program. (Table 2)

Education

The grand majority of participants (97%, 38/39) felt that the program increased their understanding of glaucoma, and many reflected on how newfound knowledge enhanced their motivation to adhere to their medications. “I really learned a lot about glaucoma and about my role in it,” one participant reflected. “Before it was just […] this vague disease that I had to deal with and that I was going to go blind […]. Now I’ve got a lot more understanding of what it is, what I can do, what’s going on.” Another stated, “I have more respect for glaucoma and for what it does. […] I think every patient should go through that program. Specially […] I learned that the brain fills in [the blind spots in the visual field]. […] That was kind of a dramatic revelation for me.”

Participants commonly discussed three educational elements from the in-person sessions as crucial to the program: (1) conversations with the glaucoma coach, (2) an audio-visual display simulating vision loss from glaucoma, and (3) coaching on how to instill eye drops. “There are questions that I had not thought to ask my doctor, but that have gotten answered and have created more incentive to be faithful and scheduled about my medications,” one participant stated. Another commented, “Getting a simulation view of a street and seeing how [uncontrolled] glaucoma might affect your vision. It was kind of the blank out spot that was really creepy. It’s like I got to do whatever I can to avoid this.” About eye drop coaching, one recalled, “When I first started, I would put my eye drops in but I wasn’t doing them the way I was supposed to. So they told me how to correctly do the right way. So after that I just didn’t have any problems.” (Table 2)

An important theme that emerged was that participants felt that the personalized didactic components of the program should be included as a standard part of glaucoma care. “[Before the SEE program] I really felt like doctor was making something up. And if [the SEE program personalized educational information] was all presented with that initial diagnosis as part of the office visit, it would be most helpful. […] ‘I’m giving you this material and then here, […] you might want to take this home, study it further, come to an understanding of it, and then maybe, [it would be helpful if the office called back to check in and ask] ‘how’s it going?’ on the phone.’” Although four participants stated that they began the program believing that they did not require glaucoma education, three of these same participants commented on the value of watching the vision loss simulation, and felt that participation in the program made a positive impact in their motivation to adhere to medications. As one stated, “I’ve had glaucoma for so long and I’m a nurse, so I think the combo made me feel like I had a lot of knowledge about it. But I think when it showed examples of […] what it’s like as you’re getting worse with your glaucoma, or talked about things, that just reminds you how important it is to be really great with your medications.” (Table 2)

Electronic reminders and adherence score

About two-thirds of participants (72%, 28/39) stated that the medication monitor’s reminder lights, in combination with text message reminders, enhanced their adherence. “The combination of the bottle and the phone calls are what kept me on track.” Multiple participants mentioned plans to purchase bottles that had built-in alarms or set up reminders on their phones at the conclusion of the program. Comments about the reminder lights on the medication monitors were overwhelmingly positive. Text messages received specifically negative commentary by three participants. “Texts didn’t do it for me but that’s also because I’m not really a text, phone kind of person. […] It might work better for the young people who are growing up with the cell phone in their hands from birth.” (Table 2) Participants also saw the bottle reminders as in integral part of the SEE Program - one participant even remarked that “it’s not just the bottle reminding me, it’s like [the glaucoma coach is] reminding me.”

Several participants mentioned that because others could see and hear the light and sound alarms on the bottles, they sparked discussion about glaucoma with their social support network. In some cases, these conversations led to participants’ family and/or friends reminding them to adhere to their medications (Table 2).

The medication monitor’s size, which was much larger than a standard eye drop bottle, served as a visual reminder for some participants, preventing them from overlooking or losing their medications. Four participants found the large bottles cumbersome, stating that they could not contain them in a pocket or small bag (Table 2). Another commented on the need for reminders from the glaucoma coach in order to maintain the bottles’ charge.

Thirty-three (of 39) participants felt that the adherence score reported during each counseling session accurately reflected their medication use. Thus, it could serve as a motivator, often by either validating or negating presumed improved adherence. “Really for me it was motivation and thinking about why […] the numbers were the way they were.”

Barriers to SEE Program participation

One third of participants (33%, 13/39) cited specific barriers that they felt made program participation more difficult. Those stated by more than one participant were: travelling to appointments (n=5), scheduling sessions (n=2), confusion regarding drop administration timing (n=2), remembering appointments (n=2), and taking time to attend appointments (n=2).

When asked if they preferred appointments scheduled in conjunction with regularly-scheduled glaucoma care appointments, 12 (of 30 participants queried) preferred separate appointments, eight would have preferred combined appointments, and ten had no preference (Table 3). Two of the five participants who cited travel as a barrier still preferred appointments scheduled separately. Overall, those who preferred separate appointments thought visits would be too long if combined.

A few participants discussed challenges or misunderstandings that became barriers to their program participation. (Table 2) Seven participants mentioned that they did not trust the adherence score, did not understand the way it was calculated, or expressed that it was not an important measurement. “I was feeling like I was getting my drops in every day. It’s just not on schedule.” Two participants expressed negative views of check-in phone calls (one participant stated that they generally do not like phone calls, and the other was frustrated that the call content seemed redundant). One participant reported only attending the sessions because they were receiving payment for attendance.

Resource use

All 39 participants were given a login and password to be able to access all of the educational materials from the SEE Program at any time, but only a minority (20%, 8/39) referred to these materials (Table 3). Four participants mentioned showing the website materials to family members. Many participants cited barriers to using the internet in general, including one participant who did not have a computer. Participants seemed to feel reviewing the educational materials on their own was not an important component of the program. “You know, I’m - I am visually impaired. I don’t use a computer much” one participant stated.

At each counseling session, participants received a printout of their written action plan about concrete next steps to improve their adherence as well as a printout of questions to ask their ophthalmologist. Most participants recalled receiving the plan page (91%, 31 of 34 queried), and ten participants (29%) referred to it regularly; these participants used the page to remember their adherence plan, medication names, and questions for their doctor (Table 3). One participant stated that since the plan page comprised a plan they had created they did not need to be reminded of it.

Comparing experiences between groups stratified by adherence improvement

When grouped based on change in adherence, most participants (n=21) fell into the Considerable Improvement group, with fewer in the Slight Improvement group (n=11), No Improvement (n=6), and Adherence Decline (n=1) groups (Table 4). There was no significant difference in age, education, race, ethnicity, insurance status, income, or sex across the three groups consisting of more than one participant (Table 1). The only significant difference between groups was that those in the Considerable Improvement group had lower baseline adherence (p=0.04) (Table 1).

Table 4.

Adherence change stratification joint display

| Group | Adherence change | Number of participants | Statements regarding anticipated change | Trust in adherence score | Suggestions for improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence Declined | <0% | 1 | “I don’t think I’ve learned a lot more.” | “So, she was telling me I’m only 67%. I’m like, ‘No I’ve been taking it.’” | “I think the program overall is okay. Some of the questionnaires were hard to answer.” |

| No Improvement | 0% to < 5% | 6 | “I had my own routine [for the past 4 years] that worked for me and she stayed with it and it’s been a good, steady and I don’t miss in the days too much. So it worked out for me.” | “I was getting my drops in every day. It’s just not on schedule. So I was maybe a little bit confused about the whole purpose of the whole thing, you know, adhering to the schedule versus just having a sympathetic person to talk to […] I don’t know though if that means that I was not within a couple, an hour or so of the times that we established arbitrarily.” | “The long survey […] Some of them were repeated, same information that they asked but maybe different form.” |

| Slight Improvement | 5% to 20% | 11 | “I walked into this and it was clearly outlined for me, ‘No, we had to do something different.’” | “It’s kind of a competitive […]. I’m only doing 87%, that’s not good, I need to do more. And then the next time when it will be higher, I will be like ‘Woohoo!’ […] Really for me it was motivation and thinking about why it was the way it was. The numbers were the way they were.” | “It’s maybe hard to do this, but let people know some of the real benefits people have had [from participating in the program].” |

| Considerable Improvement | >20% | 21 | “[To improve my adherence] I had to kind of reevaluate my schedule, you know.” | “When I hit my first 100 [% adherence], it’s kind of like okay I can do this. And then it’s kind of motivated me more even to make sure that I take it every single night during my little time window when it’s catching me in compliance.” | “Seemed like I was taken through the physics of it kind of halfway through this year. Maybe doing it earlier would be […] helpful in changing my ways.” |

Many themes were consistent across adherence groups. The main differences between participants in these categories were the attitudes toward the adherence score and the magnitude of perceived need to change their adherence behavior (Table 4).

Participants’ suggestions toward program improvement differed markedly between groups (Table 4). Most participants in the No Improvement group suggested shortening the surveys administered as part of the research process; they did not understand that the surveys were part of the research and not part of the program. The two participants in the No Improvement group with unique suggestions focused on reminders about two aspects of the program: (1) the ability to call the glaucoma coach outside of scheduled sessions and (2) the ability to visit the educational website. In the groups with more adherence improvement, suggestions for strengthening the program were much more in-depth and many focused on specific topics such as including a support group as part of the program, sending reminder emails about the appointments, sending reminders to check the educational content on the website, including family members in the program, seeing the doctor as part of the program and giving a personalized forecast of the chance each participant had of losing eyesight in the future.

As adherence improvement increased across groups, the percentage of participants who trusted the adherence score also increased: 0% (0 of 1 queried) in the Adherence Declined group, 25% (1 of 4 queried) in the No Improvement group, 80% (8 of 10 queried) in the Slight Improvement group, and 90% (19 of 21 queried) in the Considerable Improvement group (p=0.008; Table 4). Self-reported attitude toward personal change differed between groups among those who discussed it. A theme common amongst those demonstrating Considerable Improvement was the idea that from the beginning, the participant planned to change their entire medication routine and create a new schedule, rather than continuing with their established medication routine (Table 4).

The single participant in the No Improvement category expressed mistrust in the medical system overall. They did not feel that the glaucoma coach understood what medications they were on, felt that most of the physicians they had seen did not understand their specific type of glaucoma, and believed the medications were not likely to work. “I can try to adhere to the medication, but I’m not 100% confident that these medications will actually prevent the glaucoma from getting worse. I feel that part is something I don’t have any control of. The medication is - we don’t know enough to really control it anyway.”

Discussion

Understanding participants’ experiences in the SEE personalized glaucoma coaching program is crucial to understand intervention effects and planning future iterations of the program. Participant experiences were nearly entirely positive. They expressed great satisfaction with how the glaucoma coach supported them to improve their adherence. Previously poorly-adherent glaucoma patients reflected on their own change during the program, discussing how they navigated their barriers to adherence and found the motivation to improve through their discussions with the glaucoma coach. Personal change as a concept overlapped heavily with nearly all of the other concepts coded, illustrating how participants saw many of the program’s elements as playing a crucial role in their health behavior change. Overlap of other concepts with one another demonstrates how the value of the program to participants came not just from a single aspect of the program; rather, it came from the different components working in concert.

Participants conveyed how the personal connection with the glaucoma coach, the time set aside for the discussion, the tailored education and solutions and the electronic reminders and monitoring feedback (“knowing their adherence score”) helped them to improve their medication adherence. Those whose medication adherence improved the most were those who were the most highly engaged with the program - they offered the most nuanced feedback and had the most positive attitude about trying to “beat” their last adherence score. Groups that improved the least were much more likely to express a lack of interest in learning or dramatically changing their approach to self-care.

Participants were not only positive in their reception of personalized education, but seven participants expressed a wish for this personalized education to be part of standard glaucoma care. As such, working toward improving glaucoma education should be prioritized. In an observational study of physician encounters with glaucoma patients, physicians spent an average of 5.8 minutes speaking with patients.34 In these sessions, nearly all of the physicians’ questions were closed-ended and fewer than 20% of visits included solicitation of patient questions.34 Another study demonstrated that glaucoma patients and physicians discussed vision-related quality of life at just 13% of visits.35 The present study’s participants echoed these findings, as they contrasted their time-limited conversations with physicians with the more leisurely and personalized SEE program sessions. They expressed that building a partnership and rapport with the glaucoma coach, as well as having ample time to ask questions, enhanced their understanding of glaucoma, their motivation to adhere to medications, and their ability to develop an action plan for improving their adherence.

Currently, there is not enough time in clinic for physicians to provide education, brainstorm solutions to perceived adherence barriers, and coach patients in eye drop use, as well as make the medical and surgical decisions necessary to treat glaucoma. And yet, participants valued these components of the SEE program, expressing that they were critical to improving their medication adherence. In-person appointments with healthcare extenders, such as a glaucoma coach, could increase the eye care system’s capacity to deliver high quality, patient-centered care. Participants, even some who cited travel to appointments as a difficulty, preferred and valued in-person visits with the glaucoma coach. This finding echoes previous work by Sleath and colleagues who found that that glaucoma patients preferred in-person education over education delivered electronically or via printed handouts.36

It is worth noting that participants in the SEE program overwhelmingly indicated that they did not refer to the online or printed resources outside of in-person sessions. Some participants remarked on barriers to internet use, and one directly stated that they would not have watched the educational videos if instructed to do so over the phone. This reflects a national study conducted in 2017 indicating that the majority of adult patients in the United States do not regularly use their online patient portals, and that nonuse could serve to perpetuate healthcare disparities.37 Solely internet-based education will exclude a large proportion of patients.

Healthcare navigation was also an important part of the glaucoma coach’s role in some participants’ experiences. Though this was not the intentional role of the glaucoma coach, participants appreciated this resource. Healthcare navigators can support patient autonomy by being available to help when the patient asks and in a way that supports the patient’s own preferences and choices. Patient navigators have been found to reduce disparities and improve outcomes in oncology care.38 Similarly, they have reduced barriers to care and improved retention in HIV treatment programs.39 As a trusted healthcare provider, an important role for the glaucoma coach in the future will also be to serve as a healthcare navigator, helping patients access prescriptions and appointments if they are having issues.

Previous studies in glaucoma patients have identified electronic adherence reminders and monitoring as effective in improving medication adherence.40,41 Participant perspectives from the SEE program indicate that perhaps incorporating MI and education allowed participants to become motivated to engage with this adherence strategy. Some perceived the electronic reminders as coming directly from the glaucoma coach, therefore enhancing their sense of accountability. Other participants stated that they used electronic reminders prior to the program, but participation in the SEE program still increased these individuals’ adherence scores. Additionally, some participants mentioned how conversations with the glaucoma coach enabled them to find solutions to missing reminders or forgetting bottles at home. While Cook et al.’s 2016 randomized controlled trial found MI alone ineffective in improving medication adherence, and electronic reminders effective, it did not test these approaches in conjunction, and the participants enrolled in the trial had high baseline adherence.42 In our study, using an MI-based approach combined with electronic reminders lead to a large increase in adherence among those with poor adherence at baseline.

Participants’ stories demonstrated how the use of MI evoked behavior change. The MI process involves engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning.18 Engagement refers to the establishment of a collaborative and trusting relationship between participant and clinician; participants referring to the glaucoma coach as their friend or partner, was one indicator of successful engagement. The focus of the sessions was on improving medication adherence, and participants’ engagement in identifying their specific barriers and creating their own plans for overcoming these barriers demonstrates successful focusing by the glaucoma coaches. Participants’ personal change stories and comments on how they were motivated to improve their adherence was evidence of how the glaucoma coach evoked conversation regarding motivation to change. Participants description of their action plan and how they re-assessed their action plan during in-person and over-the-phone follow-up sessions signifies successful use of the planning component of MI.

The few participants who demonstrated less improvement demonstrated less trust and engagement with the program. This lack of trust was particularly evidenced by these participants’ likelihood to state that the adherence score did not matter. Lower engagement was apparent from the limited suggestions that the No Improvement group provided on how to improve the program, whereas other participants had many wonderful ideas for making the program stronger. Ideas for making the program stronger that we are considering for the next iteration of the SEE Program included adding family members in the program, sending reminder emails about appointments and availability of educational contents on the website, and making sure participants know that their doctor is in the loop on barriers that arise to adherence. Another way we will improve the program to better address the needs of participants with low readiness to change will be by giving glaucoma coaches additional training and supervision on techniques to engage those most resistant to behavior change.

There are several limitations to the present study. Nearly one-fifth (19%) of participants who originally enrolled were lost to follow up, a common occurrence in studies with patients poorly adherent to medical recommendations. There were a number of research assistants who conducted the interviews, and this could have led to variability in the information elicited from participants. Three different glaucoma coaches worked on the study at different times, and due to the integral nature of the glaucoma coach to the program, this likely affected participant experiences. This could also represent a strength of the program, however, as participant feedback was positive across the three glaucoma coaches, indicating that glaucoma coach training and the personalized education tool used helped all providers deliver high-quality counseling and education.

The participants’ experience highlights the importance of the patient-coach relationship. the technique of combining tailored, personalized education and motivational interviewing based coaching helped motivate participants to engage with the reminder and feedback system to improve their adherence. This next step is to test the SEE program in a randomized controlled trial and the effect over time on medication adherence as well as on patients’ satisfaction with their glaucoma care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the input from Chamisa MacKenzie, MSW, MPH about motivational interviewing and the statistical advice from Leslie M. Niziol, MS.

Financial Support: Funding Agency: National Eye Institute (K23EY025320, PANC) and Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (PANC). The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict(s) of Interest: The authors have no relevant funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Meeting Consideration: A portion of this material will be presented at the Association for Vision in Research and Ophthalmology Annual Meeting May 3–7, 2020, Baltimore, MD.

References

- 1.Kingman S Glaucoma is second leading cause of blindness globally. World Health Organ Bull World Health Organ Geneva. 2004;82(11):887–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevalence of Open-Angle Glaucoma Among Adults in the United States | Glaucoma | JAMA Ophthalmology | JAMA Network. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/416231. Accessed September 3, 2019.

- 3.Stewart WC, Chorak RP, Hunt HH, Sethuraman G. Factors Associated With Visual Loss in Patients With Advanced Glaucomatous Changes in the Optic Nerve Head. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116(2):176–181. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)71282-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okeke CO, Quigley HA, Jampel HD, et al. Adherence with Topical Glaucoma Medication Monitored Electronically: The Travatan Dosing Aid Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Monane M, et al. Treatment for glaucoma: adherence by the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(5):711–716. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.83.5.711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DS, Nordstrom B, Mozaffari E, Quigley HA. Glaucoma Management among Individuals Enrolled in a Single Comprehensive Insurance Plan. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(9):1500–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz GF, Quigley HA. Adherence and Persistence with Glaucoma Therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(6):S57–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman DS, Quigley HA, Gelb L, et al. Using Pharmacy Claims Data to Study Adherence to Glaucoma Medications: Methodology and Findings of the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study (GAPS). Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2007;48(11):5052. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi GCM, Pasinetti GM, Scudeller L, Radaelli R, Bianchi PE. Do Adherence Rates and Glaucomatous Visual Field Progression Correlate? Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):410–414. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2010.6112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleath B, Blalock S, Covert D, et al. The relationship between glaucoma medication adherence, eye drop technique, and visual field defect severity. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2398–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atun R Transitioning health systems for multimorbidity. The Lancet. 2015;386(9995):721–722. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62254-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rooij T van, Marsh S. eHealth: past and future perspectives. Pers Med. 2016;13(1):57–70. doi: 10.2217/pme.15.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistry N, Keepanasseril A, Wilczynski NL, Nieuwlaat R, Ravall M, Haynes RB. Technology-mediated interventions for enhancing medication adherence. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(e1):e177–e193. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocu047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckers HJM, Webers CAB, Busch MJWM, Brink HMA, Colen TP, Schouten JSAG. Adherence improvement in Dutch glaucoma patients: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2013;91(7):610–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim MC, Watnik MR, Imson KR, Porter SM, Granier AM. Adherence to Glaucoma Medication: The Effect of Interventions and Association With Personality Type. J Glaucoma. 2013;22(6):439. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31824cd0ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lunnela J, Kääriäinen M, Kyngäs H. Web-based intervention for improving adherence of people with glaucoma. J Nurs Healthc Chronic Illn. 2011;3(2):119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-9824.2011.01097.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moral RR, Torres LAP de, Ortega LP, et al. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing to improve therapeutic adherence in patients over 65 years old with chronic diseases: A cluster randomized clinical trial in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(8):977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan RM, Patrick H, Deci EL, Williams GC. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on Self-Determination Theory. :23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Self-Determination Theory Applied to Health Contexts: A Meta-Analysis - Johan Y. Y. Ng, Nikos Ntoumanis, Cecilie Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Edward L. Deci, Richard M. Ryan, Joan L. Duda, Geoffrey C. Williams, 2012. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1745691612447309. Accessed September 3, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Newman-Casey PA, Niziol LM, Mackenzie CK, et al. Personalized behavior change program for glaucoma patients with poor adherence: a pilot interventional cohort study with a pre-post design. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4:128. doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0320-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pope C, Royen P van, Baker R. Qualitative methods in research on healthcare quality. BMJ Qual Saf. 2002;11(2):148–152. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.2.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive Validity of A Medication Adherence Measure in an Outpatient Setting. J Clin Hypertens Greenwich Conn. 2008;10(5):348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Newman-Casey PA, Robin AL, Blachley T, et al. The Most Common Barriers to Glaucoma Medication Adherence: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(7):1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang DS, Friedman DS, Frazier T, Plyler R, Boland MV. Development and Validation of a Predictive Model for Nonadherence with Once-Daily Glaucoma Medications. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1396–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman-Casey PA, Killeen O, Miller S, et al. A Glaucoma-Specific Brief Motivational Interviewing Training Program for Ophthalmology Para-professionals: Assessment of Feasibility and Initial Patient Impact. Health Commun. 2018;0(0):1–9. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1557357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallo J, Lee SY. Mixed Methods in Behavioral Intervention Research. In: Behavioral Intervention Research: Designing, Evaluating, and Implementing. Springer Publishing Company; 2015:200–201. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryant A, Charmaz K. The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London England EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2007. doi: 10.4135/9781848607941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman A, Hadfield M, Chapman C. Qualitative research in healthcare: an introduction to grounded theory using thematic analysis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(3):201–205. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2015.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. 4. paperback printing; New Brunswick: Aldine; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charmaz K, Belgrave LL. Qualitative Interviewing and Grounded Theory Analysis. In: The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft. SAGE; 2012:347–362. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foley G, Timonen V. Using Grounded Theory Method to Capture and Analyze Health Care Experiences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1195–1210. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedman DS, Hahn SR, Quigley HA, et al. Doctor-Patient Communication in Glaucoma Care: Analysis of Videotaped Encounters in Community-Based Office Practice. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(12):2277–2285.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sleath B, Sayner R, Vitko M, et al. Glaucoma patient-provider communication about vision quality-of-life. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sleath B, Davis S, Sayner R, et al. African American Patient Preferences for Glaucoma Education. Optom Vis Sci Off Publ Am Acad Optom. 2017;94(4):482–486. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anthony DL, Campos-Castillo C, Lim PS. Who Isn’t Using Patient Portals And Why? Evidence And Implications From A National Sample Of US Adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(12):1948–1954. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freeman HP. Patient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2006;21(1):NaN–NaN. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV System Navigation: an emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21 Suppl 1:S49–58. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boland MV, Chang DS, Frazier T, Plyler R, Jefferys JL, Friedman DS. Automated Telecommunication-Based Reminders and Adherence With Once-Daily Glaucoma Medication Dosing: The Automated Dosing Reminder Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(7):845–850. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varadaraj V, Friedman DS, Boland MV. Association of an Electronic Health Record-Linked Glaucoma Medical Reminder With Patient Satisfaction. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(3):240–245. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.6066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cook PF, Schmiege SJ, Mansberger SL, et al. Motivational interviewing or reminders for glaucoma medication adherence: Results of a multi-site randomised controlled trial. Psychol Health. 2017;32(2):145–165. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2016.1244537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.