Abstract

Background

The number of opioid-involved overdose deaths in the United States remains a national crisis. The HEALing Communities Study (HCS) will test whether Communities That HEAL (CTH), a community-engaged intervention, can decrease opioid-involved deaths in intervention communities (n = 33), relative to wait-list communities (n = 34), from four states. The CTH intervention seeks to facilitate widespread implementation of three evidence-based practices (EBPs) with the potential to reduce opioid-involved overdose fatalities: overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND), effective delivery of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and safer opioid analgesic prescribing. A key challenge was delineating an EBP implementation approach useful for all HCS communities.

Methods

A workgroup composed of EBP experts from HCS research sites used literature reviews and expert consensus to: 1) compile strategies and associated resources for implementing EBPs primarily targeting individuals 18 and older; and 2) determine allowable community flexibility in EBP implementation. The workgroup developed the Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA) to organize EBP strategies and resources to facilitate EBP implementation.

Conclusions

The ORCCA includes required and recommended EBP strategies, priority populations, and community settings. Each EBP has a “menu” of strategies from which communities can select and implement with a minimum of five strategies required: one for OEND, three for MOUD, and one for prescription opioid safety. Identification and engagement of high-risk populations in OEND and MOUD is an ORCCArequirement. To ensure CTH has community-wide impact, implementation of at least one EBP strategy is required in healthcare, behavioral health, and criminal justice settings, with communities identifying particular organizations to engage in HCS-facilitated EBP implementation.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, Overdose, Continuum of care, Naloxone, Medication, Retention, Prescription opioid safety, Evidence-based practice, Helping to end addiction long-term, HEALing communities study

1. Background

The high number of deaths from opioids has been declared a public health crisis in the United States (Gostin et al., 2017). More than 450,000 people died from an opioid overdose from 1999 to 2018, with nearly 47,000 deaths in 2018 alone (Wilson et al., 2020). The Helping End Addictions Long Term (HEALing) Healing Communities Study (HCS), jointly supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), will test the ability of the Communities That HEAL (CTH) intervention to decrease opioid-involved deaths in communities from four research sites, located in Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. The CTH intervention follows a community engagement framework, modeled in part on the evidence-based Communities That Care model, which assists communities in adopting evidence based practices (EBPs) to prevent drug use (Hawkins et al., 2009). The CTH intervention seeks to promote a common vision, shared goals, and tailored strategies to mobilize HCS communities to adopt and implement EBPs using a stepwise community change process integrating three components: 1) community engagement; 2) the Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA); and 3) communication campaigns to increase awareness and demand for EBPs and to reduce stigma (The HEALing Communities Study Consortium, 2020).

To reduce opioid-involved overdose fatalities, three EBPs, primarily targeting individuals 18 and older, will be promoted as part of the ORCCA: 1) overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND); 2) effective delivery of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including agonist / partial agonist medication; and 3) prescription opioid safety. Naloxone is an opioid overdose antidote that works by blocking and displacing opioid agonists at the mu opioid receptor within seconds after administration. OEND was developed as a harm-reduction strategy by communities of people who use opioids and advocacy agencies in the late 1990s empowering people who use drugs and their social networks to rescue people who overdose (Dettmer et al., 2001; Maxwell et al., 2006). While no community-level randomized controlled trials have been completed, several quasi-experimental studies have demonstrated that opioid-involved overdose death rates and emergency department visits have decreased in communities where people receive OEND compared to those that do not (Bird et al., 2016; Clark et al., 2014; Coffin et al., 2016; Giglio et al., 2015; McDonald and Strang, 2016; Walley et al., 2013b). As a result, OEND is recommended as a key strategy to address opioid overdose by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2018), the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2014), the American Medical Association (American Medical Association, 2018), the American Society of Addiction Medicine (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2016), and the American Pharmacists Association (American Pharmacists Association, 2019). In July 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that it is requiring opioid pain medicine and MOUD labeling to be updated to include the recommendation that health care professionals discuss the availability of naloxone with patients and caregivers as a routine part of prescribing the medications (Food and Drug Administration, 2020).

Methadone and buprenorphine, two of the three FDA-approved medications for treating opioid use disorder (OUD), decrease all-cause and overdose mortality for persons with OUD (Larochelle et al., 2018; Pearce et al., 2020; Sordo et al., 2017). There is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about the impact of naltrexone (specifically, extended-release naltrexone), the third FDA-approved medication for treating OUD, on mortality reduction (Jarvis et al., 2018; Larochelle et al., 2018). A meta-analysis of cohort studies including 122,885 people treated with methadone found overdose mortality rates of 2.6 per 1000 person years for individuals in methadone treatment compared to 12.7 for those without treatment (Sordo et al., 2017). A meta-analysis of cohort studies including 15,831 people treated with buprenorphine revealed overdose mortality rates of 1.4 per 1000 person-years for individuals being treated with buprenorphine compared to 4.6 for individuals not in treatment (Sordo et al., 2017). A recent cohort study of 55,247 individuals receiving methadone or buprenorphine found that the risk of death when not taking MOUD was 2.1 times the risk of death when taking MOUD (Pearce et al., 2020). Notably, the relative risk of death while not taking MOUD increased to 3.4 times that when taking MOUD after illicit fentanyl became more widespread (Pearce et al., 2020). In addition, a study of 17,568 opioid-involved overdose survivors found that methadone and buprenorphine were associated with decreased all-cause and opioid overdose mortality in the first year after the nonfatal overdose (Larochelle et al., 2018). Despite evidence indicating the effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of OUD and reduction of opioid-involved overdose events, they are widely underutilized. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) estimates that 2.1 million Americans have OUD, yet fewer than 20 % of those individuals receive addiction care in a given year (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019a; Wu et al., 2016). In a cohort of opioid overdose survivors, fewer than one-third received any MOUD within a year of the overdose event (Larochelle et al., 2018). Further, protection against overdose depends on adherence to MOUD but rates of MOUD discontinuation are high (Samples et al., 2018; Wakeman et al., 2020) with risk of overdose increasing after MOUD discontinuation (Wakeman et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020). There are multiple reasons for this treatment gap (Williams et al., 2018) including the failure of EBPs to penetrate community settings that encounter people at the highest risk for overdose.

Increased opioid analgesic prescribing beginning in the 1990s played a well-documented role in fomenting the U.S. opioid epidemic. In 2001, the Joint Commission introduced standards to improve care of patients with pain (Phillips, 2000), and pain became recognized as the 5th vital sign (Veterans Health Administration, 2000). Aggressive marketing of opioids followed, promising relief from pain while minimizing adverse effects associated with opioid analgesics (Van Zee, 2009). By 2012, use of opioid analgesics was widespread, with an average of 81 opioid analgesic prescriptions dispensed per 100 persons in the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020b). As opioid analgesic prescribing surged, the prevalence of OUD and opioid overdose increased (Paulozzi et al., 2011). In response to the OUD and opioid overdose crisis, policies to curb prescription opioid use and diversion were implemented. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs, state-mandated programs that collect and report information on the dispensing of controlled substances, are now established in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Their implementation has been associated with decreased opioid prescribing, reductions in high-risk prescribing practices, and fewer episodes of “doctor-shopping” (Strickler et al., 2019). In 2016, in an effort to promote safer use of opioid analgesics, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain (Dowell et al., 2016). Key points in the guideline include recommendations to use non-pharmacologic and non-opioid therapies as 1st line treatment for chronic pain, to use caution when escalating opioid doses or prescribing high-risk drug combinations, and to limit the duration of opioid therapy for acute pain. As efforts to prevent OUD and overdose continue, strategies to reduce unnecessary prescribing and limit excess opioid analgesics in communities remain important.

In order to promote OEND, effective delivery of MOUD, and safer opioid prescribing the study team developed an approach to EBP implementation with utility for all participating communities, which vary widely in their current EBP implementation, access to resources including needed workforce, and perceived acceptability of various EBPs. This paper describes the framework developed to guide EBP selection and implementation strategies contained in the Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach.

2. Methods/design

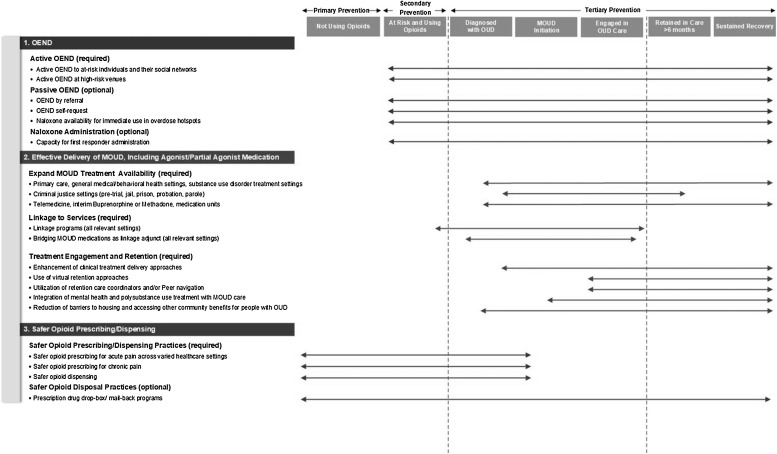

For each EBP component of the CTH intervention, a workgroup consisting of EBP experts from each research site was established to develop an approach that would include standardization requirements across communities, while also providing enough flexibility to meet the varying needs of the 67 HCS communities. A significant reduction in opioid-involved overdose deaths will require widespread implementation of OEND, effective delivery of MOUD, and prescription opioid safety efforts. Therefore, effective implementation of strategies for each of these three EBPs is an HCS goal. The first task undertaken by this workgroup was developing a framework for organizing the targeted EBPs and potential strategies for their implementation. The Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA), shown in Fig. 1 , was adapted from the Cascades of Care for OUD developed by Williams and colleagues (Williams et al., 2018). Cascades of Care emphasizes four domains: Prevention, Identification, Treatment, and Remission. The ORCCA places greater emphasis on the HCS-goal of implementing EBP strategies that will reduce opioid-involved overdose fatalities and demonstrates how overdose reduction strategies overlap across a continuum of care rather than being discrete steps. The workgroup then developed the ORCCA’s required elements and a companion Technical Assistance Guide referencing existing resources to assist communities with implementation. Based on research literature and expert consensus, the ORCCA includes required and recommended community settings, priority populations, EBPs, and implementation strategies.

Fig. 1.

The HEALing Communities Study Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA) with Sample strategies.

2.1. Required community settings

In order to ensure the CTH intervention has impact across multiple sectors interacting with individuals at high risk for an opioid-involved overdose and across the care continuum, each community is required to implement at least one of the EBPs within each of three community settings: 1) healthcare; 2) behavioral health; and 3) criminal justice. Healthcare settings include outpatient healthcare centers, pre-hospital providers, emergency departments and urgent care, hospitals, primary care settings, and pharmacies. Behavioral health includes substance use disorder and mental health treatment centers and social service agencies. Criminal justice includes pre-trial, jails, probation, parole, drug and problem-solving courts, police and “narcotics” task forces, halfway houses, community-based correctional facilities, and department of youth services. Communities provide a rationale for not engaging all three community settings.

2.2. High risk populations

Most people with OUD in the U.S. are not enrolled in effective treatment (Williams et al., 2018). Any individual misusing opioids or with OUD is at risk for opioid-involved overdose death, particularly if not engaged in MOUD. A substantial proportion of people who die from opioid-involved overdose have had no interaction with the healthcare system in the previous year (Larochelle et al., 2019). Thus, reducing overdose deaths will require engaging people who currently are not accessing overdose prevention or OUD treatment services. This reality is the justification for an ORCCA requirement to identify and intervene with high-risk populations. Individuals who are at highest risk for overdose, such as those who have overdosed or those who recently were treated in a withdrawal management program (colloquially referred to as “detox”), do not typically access MOUD (Larochelle et al., 2018; Walley et al., 2020). Specific factors that further elevate the risk of overdose among those using opioids include: 1) having had a prior opioid overdose (Caudarella et al., 2016; Darke et al., 2011; Larochelle et al., 2018; Larochelle et al., 2019; Winhusen et al., 2016); 2) having reduced opioid tolerance (e.g., completing medically supervised or “socially” managed withdrawal, or release from an institutional setting such as jail, residential treatment, hospital) (Binswanger et al., 2007; Larochelle et al., 2019; Merrall et al., 2010; Strang et al., 2003; Walley et al., 2020); 3) using other substances (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines, stimulants) (Brugal et al., 2002; Cho et al., 2020; Gladden et al., 2019; Larochelle et al., 2019; Park et al., 2020, 2015; Sun et al., 2017); 4) having a concomitant major mental illness (e.g., major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders) (O’Driscoll et al., 2001; Pabayo et al., 2013; Tobin and Latkin, 2003; Wines et al., 2007); 5) having a concomitant major medical illness (e.g., cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, COPD, asthma, sleep apnea, congestive heart failure; infections related to drug use) (Bosilkovska et al., 2012; Green et al., 2012; Jolley et al., 2015; Larochelle et al., 2019; Vu et al., 2018); and/or 6) injecting drugs (Bazazi et al., 2015; Brugal et al., 2002).

In developing the ORCCA, the workgroup delineated three approaches to identifying high risk populations (See Table 1 ). These approaches include: 1) identification within criminal justice settings and venues where high-risk populations seek services (Green et al., 2018; Malta et al., 2019; Park-Lee et al., 2016; Suffoletto and Zeigler, 2020; Weiner et al., 2020), 2) field-based outreach including point-of-contact for emergency response (, Bagley et al., 2019; Waye et al., 2019), and 3) the use of surveillance or other existing data sources to locate individuals likely needing intervention (Formica et al., 2018; Merrick et al., 2016). In the first approach, EBPs are incorporated into services at venues where people at high-risk may be present. The second approach includes real-time community outreach to high-risk venues and individuals. The third approach includes identifying newly emerging risk groups utilizing overdose surveillance data. In addition to defining populations at high risk for overdose, the ORCCA also identifies populations that would likely warrant tailoring EBP strategy implementation. These groups include adolescents (Bagley et al., 2020; Chatterjee et al., 2019; Lyons et al., 2019), pregnant and post-partum women (Goldman-Mellor and Margerison, 2019; Nielsen et al., 2020), homeless populations (Bartholomew et al., 2020; Doran et al., 2018; Magwood et al., 2020), rural populations without transportation (Arcury et al., 2005; Bunting et al., 2018) and other factors related to poverty (Snider et al., 2019; Song, 2017), veterans (Lin et al., 2019; Mudumbai et al., 2019), non-English speaking and immigrant populations (Salas-Wright et al., 2014; Singhal et al., 2016), racial and ethnic minorities (Barocas et al., 2019; Lippold et al., 2019), people with mental health disorders (Turner and Liang, 2015) and mental/physical disabilities (Burch et al., 2015; West et al., 2009), people involved in transactional sex (Goldenberg et al., 2020; Marchand et al., 2012), and people who have chronic pain (Bohnert et al., 2011; Dunn et al., 2010; James et al., 2019). As one of the HCS requirements, communities will record the high-risk populations and community venues included in the selected EBP strategies.

Table 1.

Identification of populations at heightened risk for opioid-involved overdose death.

| Identification locations |

Sample methods/resources |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes. SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; EMS = Emergency medical services; ED = Emergency department.

2.3. Development of ORCCA menu and EBP strategies

Subgroups were established for each of the three EBPs to assemble strategies and resources contained in the ORCCA. These subgroups created a forum for networking and collaboration among investigators with specific content expertise. Subgroups drafted each respective menu (OEND, MOUD, and safer opioid prescribing) and their Technical Assistance Guide subsections. Based on the likelihood of overdose reduction, the subgroups made recommendations on which strategies should be required and which should be optional. For example, the OEND subgroup recommended that “active” distribution of OEND be required, because it was concluded that reducing overdose on a community level required OEND being pro-actively provided to high-risk populations. It would not be enough to “passively” make it available regardless of overdose risk. Each subgroup reviewed the literature and completed online searches (e.g., SAMHSA website) for resources and toolkits. Upon completion of each subgroup’s section, the full workgroup convened to vote and approve the ORCCA.

2.4. The ORCCA menus

2.4.1. Overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND)

Naloxone reverses an opioid overdose if administered quickly. Overdose prevention education and broad community access to naloxone is associated with reduced opioid-involved overdose death (Bird et al., 2016; Clark et al., 2014; Giglio et al., 2015; McDonald and Strang, 2016; Walley et al., 2013b). OEND includes clear, direct messages about how to prevent opioid overdose and rescue a person who is overdosing to empower trainees to respond to overdoses. OEND can be successfully implemented at multiple venues among diverse populations. The OEND menu (see Table 2 ) includes three sub-menus: a) active OEND, which is required; b) passive OEND, which is optional; and c) naloxone administration, which is optional. The following sections describe the rationale and evidence for the OEND submenus.

-

a)

Active OEND

Table 2.

Strategies and sample resources to increase opioid overdose prevention education and naloxone distribution (OEND).

| Strategies | Sample Resources |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Active OEND for at-risk individuals and their social networks (Bagley et al., 2018, 2015; Behar et al., 2015; Coe and Walsh, 2015; Coffin and Sullivan, 2013; Commonwealth Medicine: University of Massachusetts Medical School, 2018; Doe-Simkins et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2014; McAuley et al., 2015; Mueller et al., 2015; Simmons et al., 2018; Vissman et al., 2017; Voss et al., 2013; Walley et al., 2013a) Active OEND at high-risk venues: Criminal Justice settings (Binswanger et al., 2007; Merrall et al., 2010; Vissman et al., 2017; Vissman et al., 2020) Syringe service program (Bennett et al., 2018) Emergency departments and acute care hospitals (Dwyer et al., 2015) “Leave behind” programs at sites of overdose (Bagley et al., 2019; Formica et al., 2018) Mental Health/Addiction treatment programs (Walley et al., 2013a) |

General Overview/Introduction to Active OEND

|

|

|

| OEND by referral (e.g. prescription to fill at pharmacy (Green et al., 2015; Guy et al., 2019; Mueller et al., 2015), referral to OEND dispensing program (Coffin et al., 2016; Sohn et al., 2019) | General Resources/Toolkits for OEND by referral and OEND by self-request

o Kentucky

|

| OEND self-request (e.g. at pharmacy, community meeting or public health department) (Jones et al., 2016) | |

| Naloxone availability for immediate use in overdose hotspots (NaloxBox, 2020; Salerno et al., 2018) | NaloxBox (mounted supply of naloxone) (NaloxBox, 2020) Prevent & Protect Safety Policy (Prevent and Protect, 2020) Health Resources in Action: Overdose Response Training (Health Resources in Action, 2017) |

|

|

| Capacity for first responder administration (Davis et al., 2015, 2014a; Davis et al., 2014b; Rando et al., 2015) | General Resources/Toolkits

|

Footnotes. OEND = Opioid overdose prevention education and naloxone distribution; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DAWN = Deaths avoided with naloxone.

Active OEND is proactive and targeted towards high-risk populations and their social networks or venues where high risk populations are likely to be found. Active OEND is a required ORCCA menu element because the best evidence for reducing overdose via OEND has been shown among communities that pro-actively make OEND accessible to those at high risk for overdose (Walley et al., 2013b) including people released from incarceration (Bird et al., 2016), and people with chronic pain treated with chronic opioid therapy through community health centers (Coffin et al., 2016). Opioid overdose education typically includes education about overdose risk factors and how to recognize and respond to an overdose, including naloxone administration; training can be provided in a variety of formats including in-person or on-line. Active OEND examples include: syringe service program workers providing OEND to people who inject opioids (Doe-Simkins et al., 2014; Walley et al., 2013b; Wheeler et al., 2015); emergency department staff providing OEND to patients seen for opioid-use complications (Dwyer et al., 2015; Gunn et al., 2018); and equipping people released from incarceration with naloxone (Bird et al., 2016; Wenger et al., 2019).

-

b)

Passive OEND

Passive OEND increases OEND access to individuals referred by other providers and those seeking OEND on their own and makes naloxone available for immediate use in overdose hotspots. As an optional ORCCA submenu, passive OEND strategies are encouraged but not required because their impact is unlikely to be adequate to reduce overdose deaths compared to active OEND strategies. Examples of passive OEND include distributing naloxone at a community meeting or making naloxone available at a pharmacy without a prescription (Jones et al., 2019; Pollini et al., 2020; Sohn et al., 2019), for example through pharmacy standing orders (Abouk et al., 2019; Davis and Carr, 2017; Evoy et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018). This submenu also includes publicly available naloxone for emergency use where overdoses commonly occur, such as public restrooms (Capraro and Rebola, 2018).

-

c)

Naloxone administration

The naloxone administration submenu focuses on increasing capacity for opioid overdose response and rescue by first responders such as police (Wagner et al., 2016) and fire and emergency medical technicians (Davis et al., 2015, 2014a; Davis et al., 2014b; Rando et al., 2015). In these programs, first responders are trained in overdose response and equipped with naloxone, so they have the capacity to administer naloxone when called. They do not distribute naloxone to others in the community. This is also an optional menu item because the impact is unlikely to be adequate to reduce overdose deaths compared to active OEND.

2.4.2. Effective delivery of MOUD, including agonist / partial agonist medication

MOUD decreases the risk of opioid-involved death (Larochelle et al., 2018; Pearce et al., 2020; Sordo et al., 2017) but is widely underutilized (Volkow and Wargo, 2018; Williams et al., 2018). Barriers to improved MOUD utilization include inadequate treatment availability, failure to identify and engage high-risk populations in MOUD, and poor treatment retention (Morgan et al., 2018; Samples et al., 2018). Accordingly, the MOUD menu (Table 3 ) is composed of three sub-menus: a) expand MOUD treatment availability; b) interventions to link people in need to MOUD; and c) MOUD engagement and retention. It is required that communities choose at least one strategy from each of the three MOUD submenus. Evidence for decreasing mortality is strongest for methadone and buprenorphine. Therefore, communities are required to choose strategies that expand access to, and improve retention in, treatment with these medications. Strategies that focus on naltrexone are optional since this medication has less evidence for reducing opioid-involved overdose (Larochelle et al., 2018), although clinical trials suggest extended-release injection naltrexone can be effective for relapse prevention if adherence is secured (Lee et al., 2016, 2018; Tanum et al., 2017). The following sections describe the rationale and evidence for the three required submenus within the MOUD menu.

-

a)

Expand MOUD treatment availability (capacity building)

Table 3.

Strategies and sample resources to enhance delivery of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) maintenance treatment.

| Strategies | Sample Resources |

|---|---|

|

|

| Adding/expanding MOUD treatment in primary care, other general medical and behavioral/mental health settings (Brooklyn and Sigmon, 2017; Heinzerling et al., 2016; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine et al., 2019; Townley and Dorr, 2017) and in specialty addiction/ substance use disorder treatment settings and recovery programs (Clark et al., 2010; SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions, 2014) |

|

| Adding/expanding MOUD treatment in Criminal Justice settings (e.g., pre-trial, jail, prison, probation, parole) (Binswanger, 2019; Green et al., 2018; Marsden et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2019; Rich et al., 2015) |

|

| Expanding access to MOUD treatment through telemedicine, interim buprenorphine or methadone, or medication units |

|

|

|

| Linkage Programs (all relevant settings) |

Within (or initiated within) Service Settings

|

| Starting individuals on MOUD as an adjunct to linkage programs (all relevant settings) (Busch et al., 2017; Cushman et al., 2016; D’Onofrio et al., 2015; Gordon et al., 2017; Weinstein et al., 2018; Zaller et al., 2013) |

Within (or initiated within) Service Settings

|

|

|

| Enhancement of clinical delivery approaches that support engagement and retention (Plater-Zyberk et al., 2012; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020) |

|

| Use of virtual retention approaches (e.g., mobile, web, digital therapeutics) (Pear Therapeutics, 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, date unknown) |

|

| Utilize retention care coordinators |

|

| Mental health and polysubstance use treatment integrated into MOUD care (Krawczyk et al., 2017; Sullivan et al., 2010) |

|

| Reducing barriers to housing, transportation, childcare and accessing other community benefits for people with opioid use disorder |

|

Footnotes. MOUD = Medication for opioid use disorder; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; ECHO = Extension for community healthcare outcomes; HRSA = The Health Resources and Services Administration.

Communities must select at least one strategy that expands MOUD treatment availability with buprenorphine or methadone from this submenu. Though each potential strategy includes multiple venues, the ORCCA does not prescribe which venues must be included outside of the overall requirement that communities choose at least one strategy that addresses healthcare, behavioral health, and criminal justice settings across all three main menus. The first submenu strategy is adding and/or expanding MOUD treatment in primary care, other general medical and mental health settings and substance use disorder treatment and recovery programs. Historically in the US, addiction treatment has been isolated from general medical and mental health care settings, and MOUD treatment has been omitted from the care provided in primary care, hospitals (Fanucchi and Lofwall, 2016; Jicha et al., 2019), emergency departments (Hawk et al., 2020), and general mental health (Novak et al., 2019). Furthermore, according to data from the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities, many substance use disorder treatment programs do not provide MOUD (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019c). Specifically, in 2018, the proportion of facilities offering buprenorphine, methadone, and long-acting naltrexone treatment was 33 %, 10 %, and 28 % respectively (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019c). MOUD treatment can be successfully integrated in these settings, increasing capacity and reducing treatment barriers (Blanco and Volkow, 2019; Chou et al., 2016b; Korthuis et al., 2017).

The second submenu strategy is adding and/or expanding MOUD treatment in criminal justice settings. Despite the strong evidence base, MOUD is not commonly provided in criminal justice settings, with only 30 out of 5100 US prisons and jails offering methadone or buprenorphine in 2017 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019e). Incarceration is associated with increased risk of overdose death post-release largely due to loss of tolerance after forced withdrawal during incarceration (Binswanger et al., 2013; Merrall et al., 2010). Improving availability of MOUD in criminal justice settings, including pre-trial, jail, prison, probation, and parole, is a critical opportunity to reduce opioid-involved overdose deaths (Moore et al., 2019).

The third submenu strategy is expanding access to MOUD treatment through telemedicine, interim buprenorphine (Sigmon et al., 2016), interim methadone (Newman, 2014; Schwartz et al., 2006), or medication units (Office of the Federal Register and Government Publishing Office, 2019b). Expanding access to MOUD through telemedicine is especially salient as communities consider ORCCA strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemedicine models for buprenorphine treatment already existed (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018), but guidance from the US Drug Enforcement Agency, SAMHSA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and state regulatory agencies changed rapidly (Harris et al., 2020; Opioid Response Network, 2020; Providers Clinical Support System, 2020a; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020c) to allow greater flexibility of MOUD treatment via telemedicine during the pandemic. For example, the requirement for an in-person visit to begin MOUD was waived and dispensing of medications was allowed for longer periods of time. It is unclear how effective these changes will be or whether they will remain, but telemedicine is part of the OUD treatment landscape and an important tool to support treatment access. “Interim” treatment with methadone or buprenorphine refers to treatment with medication dispensed directly to patients (no prescription given) at licensed opioid treatment programs, which are heavily regulated at a federal and state level and require comprehensive ancillary services (e.g., on-site counseling). When there are waiting lists, these programs may receive regulatory approval to provide medication for up to 180 days while patients await the full array of non-medication services. This is called “interim” treatment and is superior to waiting lists on multiple outcomes including illicit opioid use and treatment retention (Sigmon, 2015). A medication unit is a satellite to a licensed opioid treatment program providing primarily medication dispensing in order to make treatment more accessible to patients (Office of the Federal Register and Government Publishing Office, 2019b). New patients are required to have direct supervision of their daily dispensed medication for the first 90 days of treatment, making travel a barrier to treatment if the program is located far away from the patient. Therefore, medication units are a way to extend the availability of methadone treatment over a wider geographic region.

-

b)

Interventions to link to MOUD

The second submenu focuses on strategies that link people with OUD to MOUD. There are two strategies to choose from: improving linkage to MOUD from venues where persons with OUD may be encountered (e.g., general medical and mental health treatment programs, syringe service programs, and criminal justice settings); and using MOUD initiation as a bridge to longer-term care (starting MOUD at the venue where the patient is encountered in addition to linkage to ongoing MOUD treatment). On-site MOUD initiation strategies are preferred and can occur across multiple community-based settings such as in emergency departments and hospitals where patients may present with complications of untreated OUD such as an opioid overdose or a deep-seated infection related to intravenous injection of opioids. Starting MOUD in these venues is safe, feasible, and can significantly increase likelihood of continuing MOUD treatment (D’Onofrio et al., 2015; Weinstein et al., 2018).

-

c)

MOUD treatment engagement and retention

MOUD treatment retention beyond 6 months is challenging (Samples et al., 2018), but critical to saving lives. Research is clear that MOUD treatment retention is strongly associated with decreased mortality – both from overdose and all-cause mortality, with risk of overdose increasing dramatically after discontinuation of MOUD (Pearce et al., 2020; Wakeman et al., 2020; Walley et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020). Communities must choose at least one of the following five strategies: a) enhancement of clinical delivery approaches to support engagement and retention; b) use of virtual retention approaches; c) retention care coordinators; d) mental health and polysubstance use treatment integrated into MOUD care; and e) reducing barriers to housing, transportation, childcare, and accessing other community benefits for people with OUD. Comprehensive strategies to improve MOUD treatment retention include addressing each individual’s treatment needs, which commonly include treatment for comorbid mental health and non-opioid substance use disorders as well as reducing barriers to resources such as housing, transportation, insurance coverage, food security, childcare, employment and other psychosocial and community services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020d). Shared decision making, case management, legal assistance and advocacy, on-site psychiatric services and psychosocial recovery support, insurance navigation, behavioral interventions such as contingency management for comorbid non-opioid substance use disorders (De Crescenzo et al., 2018), and technology-delivered therapies (Christensen et al., 2014) are some example strategies aimed at improving engagement and retention.

2.4.3. Prescription opioid safety

Opioid analgesic prescribing practices can increase the risk of long-term opioid use, the development of OUD and opioid-involved overdose deaths. For example, an opioid analgesic prescription is associated with increased risk for OUD in persons with chronic non-cancer pain (Edlund et al., 2014) and the length of an initial opioid prescription for acute pain is a significant predictor of long-term use (Shah et al., 2017). Similarly, high doses of opioids (e.g., >90 morphine milligram equivalents) (Bohnert et al., 2016; Dasgupta et al., 2016), use of extended-release/long-acting opioids (Zedler et al., 2014) and concurrent prescribing of benzodiazepines increase the risk of overdose (Hernandez et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2017). Those with co-occurring mood disorders, other non-opioid substance use disorders, chronic medical conditions, and chronic pain are at heightened risk (Campbell et al., 2018). When prescribed opioids are not properly stored or go unused, the excess supply is a potential source for non-medical use and/or diversion; the majority of persons reporting non-medical use of prescription opioids obtain them from a friend or family member (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019a). Numerous safer opioid prescribing guidelines have been published (Chou et al., 2009; Franklin and American Academy of, 2014; Manchikanti et al., 2012; Nuckols et al., 2014), however, adherence to these guidelines is low (Hildebran et al., 2014; Sekhon et al., 2013; Starrels et al., 2011). Pain management education remains inadequate (Mezei et al., 2011), but is a key strategy to address poor adherence to guideline-based safer opioid prescribing practices. Accordingly, the prescription opioid safety menu (Table 4 ) includes two submenus: a) safer opioid prescribing/ dispensing practices, which is required, and b) safer opioid disposal practices, which is optional.

-

a)

Safer opioid prescribing/dispensing practices

Table 4.

Strategies to Improve Prescription Opioid Safety.

| Strategies | Sample Resources |

|---|---|

|

|

Safer opioid prescribing for acute pain across varied healthcare settings (Baker et al., 2016; Barth et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2017; Guy et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2018; Wunsch et al., 2016)

|

Pain management guidelines

|

Safer opioid prescribing for chronic pain (Barth et al., 2017; Bohnert et al., 2018, 2011; Dunn et al., 2010; Edlund et al., 2014; Gaiennie and Dols, 2018; Gomes et al., 2011; Guy et al., 2017; Jeffery et al., 2019; Liebschutz et al., 2017)

|

Pain management guidelines and toolkits

|

| Safer opioid dispensing (Hartung et al., 2017; Shafer et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2017) |

|

|

|

| Prescription drug drop-box / mail-back programs (Egan et al., 2018; Gray et al., 2015; Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016) |

|

Footnotes. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Communities must select at least one of the following three strategies: 1) safer opioid prescribing for acute pain across healthcare settings, such as inpatient services, emergency departments, outpatient clinics, ambulatory surgery and dental clinics; 2) safer opioid prescribing for chronic pain, including adherence to the CDC guideline recommendations and patient-centered opioid tapering; or 3) safer opioid dispensing. A variety of approaches have been effective in promoting safer opioid prescribing. For example, opioid prescribing changes were observed following implementation of the CDC 2016 chronic pain guidelines (Bohnert et al., 2018). Online and in-person continuing education has been shown to improve knowledge, attitudes, confidence and self-reported clinical practice in safer opioid prescribing (Alford et al., 2016). Academic detailing, an interactive one-on-one educational outreach by a healthcare provider to a prescriber to provide unbiased, evidence-based information to improve patient care, has been applied successfully to improve opioid prescribing behavior (Larson et al., 2018; Voelker and Schauberger, 2018). The utilization of state Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs to assess patients’ controlled substance prescription histories and identify potential risky patterns of opioid use or drug combinations has resulted in reduced multiple-provider episodes (i.e., “doctor shopping”) (Strickler et al., 2020), reduced high-risk opioid prescribing (Strickler et al., 2019), and reduced prescription opioid poisonings (Pauly et al., 2018). Prescriber feedback regarding a patient’s fatal overdose can also change prescriber behavior (Doctor et al., 2018; Volkow and Baler, 2018). Most efforts to promote safer opioid analgesic use have focused on prescriber behavior change. However, pharmacists are the last line of defense against unsafe opioid prescriptions and have a corresponding responsibility to ensure legitimate prescriptions (Office of the Federal Register and Government Publishing Office, 2011).

-

b)

Safer opioid disposal practices (optional)

Providing safe, convenient, and environmentally appropriate ways to dispose of unused prescription opioids can help reduce the excess opioid supply within communities and prevent access by children, adolescents, and other vulnerable individuals. Communities have the option of selecting a strategy to promote safe disposal practices such as the installation of permanent disposal kiosks or the implementation of other disposal programs such as distribution of drug mail-back envelopes. Studies have shown that leftover medication from an opioid prescription is common (Bicket et al., 2017; Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016) and that patient education regarding disposal practices can increase opioid disposal rates (Hasak et al., 2018), although education about disposal is suboptimal (Gregorian et al., 2020). According to a recent study, only 30 % of persons who had received an opioid prescription in the previous two years disposed of their unused opioid medication; however, over 80 % indicated they would be more likely to dispose of opioid medications in the future if disposal kiosks were in a location they visited frequently (Buffington et al., 2019).

2.5. Emerging ORCCA strategies

Because the evidence base will evolve during the course of this study, additional strategies can be added to the menus if any of the following inclusion criteria are met: 1) listed in a registry of EBPs (federal, state, or community) that documents it has been replicated multiple times with positive effects; 2) evidence of its efficacy through, at a minimum, a quasi-experimental design; 3) evidence of its efficacy in reducing opioid-involved overdose death that has been published in a scientific journal; or 4) it has been reviewed and approved by the ORCCA Steering Committee.

2.6. ORCCA technical assistance guide

Upon completion of the ORCCA menus, the subgroups developed a companion Technical Assistance Guide which provides greater detail about the resources included in the ORCCA menus (i.e., the resources listed in the “Sample Resources” column of Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4). The resources compiled in the Guide (e.g., toolkits, publications, websites) are designed to help implement and sustain each EBP and strategy included on an ORCCA menu and provides examples of successful national, state, and local programs. The Guide is considered a “living document” and is updated every six months by a dedicated subgroup spanning the research sites.

3. Discussion

The HCS seeks to facilitate widespread uptake and expansion of three EBPs with the potential to reduce opioid-involved overdose fatalities: 1) OEND; 2) effective delivery of MOUD, including agonist / partial agonist medication; and 3) prescription opioid safety. This paper described the development of the ORCCA, which includes a menu-based approach to organizing strategies and resources for facilitating implementation of these EBPs. The ORCCA includes requirements and recommendations for EBP implementation to help ensure standardization across the research sites. At minimum, five strategies need to be selected to implement the three EBPs: one for OEND, three for MOUD, and one for prescription opioid safety. Based on a literature review and expert consensus, the ORCCA requires identification, and engagement of, high-risk populations in healthcare, behavioral health, and criminal justice settings, which will help ensure both that individuals most in need of services receive them and that implementation of EBPs will be more widespread in communities than could be achieved by allowing implementation within a narrower range of settings.

Importantly, the ORCCA does not prescribe the implementation of any single strategy; rather, it provides flexibility with multiple strategy options for implementing the required EBPs, all of which were chosen based on the scientific evidence. Because each community will vary in the need, feasibility, readiness, desirability, stage of current implementation, and expected impact for specific practices, they will likely differ in their strategies and venues for implementing the three required EBPs. Many of the resources included in the ORCCA menus and Technical Assistance Guide have been developed to directly assist community coalitions, implementation teams, administrators, and practitioners who seek to implement or expand EBPs. In the HCS, the implementation of selected strategies will be a partnership between the community coalitions and the research site team, with the research site providing technical support. A limitation of the approach taken to ORCCA development is that a formal systematic review of the literature, such as that outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Moher et al., 2009), was not completed and, thus, potential strategies that could effectively support EBP implementation may have been missed. A strength of the approach is that, in addition to meeting the needs of the HCS communities, the ORCCA was designed for dissemination to other communities struggling with the opioid crisis should the HCS model prove effective. The flexibility included in the ORCCA, along with the resources included in the ORCCA menus and the Technical Assistance Guide, will increase the ease of implementation, with knowledgeable clinical experts in place of a research team, who partner with coalitions and organizations to select and implement practices that will achieve desired outcomes and foster sustainability.

Role of funding source

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Healththrough the NIH HEAL Initiative with the following awards: UM1DA049394, UM1DA049406, UM1DA049412, UM1DA049415, and UM1DA049417. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or its NIH HEAL Initiative.

Contributors

Drs. Winhusen, Walley, Fanucchi, Hunt, Lofwall, Freeman, and Chandler contributed to the conceptualization, design, drafting of the manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Drs. Lyons, Brown, Nunes, Saitz, Stambaugh, Alford; Ms. Beers, and Ms. Herron contributed to the conceptualization, design, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Drs. Oga, Roberts, Starrels; Mr. Baker, and Mr. Cook contributed to the design, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Trial registration

Clinical Trials.gov http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Identifier: NCT04111939.

Declaration of Competing Interest

RS reports Alkermes provided injectable naltrexone to Boston University for an NIH-funded study of which he is principal investigator. JS reports receiving research support from the Opioid Post-marketing Requirement Consortiumand having served as a core expert on the 2016 CDC Guideline committee. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abouk R., Pacula R.L., Powell D. Association between state laws facilitating pharmacy distribution of naloxone and risk of fatal overdose. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019;17:805–811. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya M., Chopra D., Hayes C.J., Teeter B., Martin B.C. Cost-effectiveness of intranasal naloxone distribution to high-risk prescription opioid users. Value Health. 2020;23:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addiction Technology Transfer Center Network . 2019. ATTC Motivational Interviewing Training.https://attcnetwork.org/centers/global-attc/products-resources-catalog [Google Scholar]

- Alford D.P., Zisblatt L., Ng P., Hayes S.M., Peloquin S., Hardesty I., White J.L. SCOPE of pain: an evaluation of an opioid risk evaluation and mitigation strategy continuing education program. Pain Med. 2016;17:52–63. doi: 10.1111/pme.12878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry . 2019. 8 Hour and 24 Hour MAT Waiver Training.https://www.aaap.org/clinicians/education-training/mat-waiver-training/ [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, State Targeted Response Technical Assistance Consortium . 2018. Opioid Response Network.https://opioidresponsenetwork.org/ (Accessed May 10, 2019) [Google Scholar]

- American College of Emergency Physicians . 2014. ACEP-ONDCP Webinar on Naloxone.https://www.acep.org/how-we-serve/sections/trauma--injury-prevention/acep-ondcp-webinar-on-naloxone/ [Google Scholar]

- American College of Emergency Physicians . 2020. E-QUAL Opioids Toolkits: Pain Management and Safe Opioid Use.https://www.acep.org/administration/quality/equal/emergency-quality-network-e-qual/e-qual-opioid-initiative/e-qual-opioid-toolkit/ [Google Scholar]

- American College of Emergency Physicians . 2020. Ending the Stigma of Opioid Use Disorder (video)https://www.acep.org/by-medical-focus/mental-health-and-substanc-use-disorders/stigma/ [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association . 2018. Prevention of Opioid Overdose D-95.987.https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/opioids?uri=%2FAMADoc%2Fdirectives.xml-0-2069.xml (Accessed June 18, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- American Pharmacists Association . 2017. APhA Balancing Risk and Access to Opioids: The Role of the Pharmacist (archived)https://web.archive.org/web/20170628110504/http://elearning.pharmacist.com/products/4724/balancing-risk-and-access-to-opioids-the-role-of-the-pharmacist [Google Scholar]

- American Pharmacists Association . 2019. APhA Policy Manual: Opioids.https://www.pharmacist.com/policy-manual?key=opioid (Accessed June 18, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- American Pharmacists Association . 2020. APhA Collaborate for Responsible Opioid Use.http://elearning.pharmacist.com/products/5160/collaborate-for-responsible-opioid-use-home-study [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Cross-Divisional Taskforce on Clinical Responses to the Opioid Crisis . 2019. The Opioid Guide: a Resource for Practicing Psychologists.https://www.apa.org/advocacy/substance-use/opioids/psychologist-guide.pdf (Accessed June 23, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- American Psycihatric Association . 2015. Treating Co-occurring Depression and Opioid Use Disorder: a Case Discussion.https://education.psychiatry.org/Users/ProductDetails.aspx?ActivityID=1361 [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Addiction Medicine . 2016. Public Policy Statement on the Use of Naloxone for the Prevention of Opioid Overdose Deaths.https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/use-of-naloxone-for-the-prevention-of-opioid-overdose-deaths-final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Addiction Medicine . 2019. Live and Online CME.https://www.asam.org/education/live-online-cme [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Addiction Medicine . 2019. Treatment in Correctional Settings Toolkit.https://www.asam.org/advocacy/toolkits/treatment-in-correctional-settings [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Addiction Medicine . 2019. Waiver Qualifying Training.https://www.asam.org/education/live-online-cme/waiver-qualifying-training [Google Scholar]

- Amston Studio LLC . 2019. Buprenorphine Home Induction App.https://apps.apple.com/us/app/buprenorphine-home-induction/id1449302173 [Google Scholar]

- Arcury T.A., Preisser J.S., Gesler W.M., Powers J.M. Access to transportation and health care utilization in a rural region. J. Rural Health. 2005;21:31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J., Beletsky L., Baker P., Abramovitz D., Artamonova I., Clairgue E., Morales M., Mittal M.L., Rocha-Jimenez T., Kerr T., Banuelos A., Strathdee S.A., Cepeda J. Interactive versus video-based training of police to communicate syringe legality to people who inject drugs: the SHIELD study, Mexico, 2015–2016. Am. J. Public Health. 2019;109:921–926. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AVOL KY Inc . 2019. AIDS Volunteers of Kentucky (AVOL KY)https://www.avolky.org/ (Accessed August 16, 2019) [Google Scholar]

- Bagley S.M., Peterson J., Cheng D.M., Jose C., Quinn E., O’Connor P.G., Walley A.Y. Overdose education and naloxone rescue kits for family members of individuals who use opioids: characteristics, motivations, and naloxone use. Subst. Abus. 2015;36:149–154. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.989352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley S.M., Forman L.S., Ruiz S., Cranston K., Walley A.Y. Expanding access to naloxone for family members: the Massachusetts experience. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37:480–486. doi: 10.1111/dar.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley S.M., Larochelle M.R., Xuan Z., Wang N., Patel A., Bernson D., Silverstein M., Hadland S.E., Land T., Samet J.H., Walley A.Y. Characteristics and receipt of medication treatment among young adults who experience a nonfatal opioid-related overdose. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020;75:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley S.M., Schoenberger S.F., Waye K.M., Walley A.Y. A scoping review of post opioid-overdose interventions. Prev. Med. 2019:105813. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J.A., Avorn J., Levin R., Bateman B.T. Opioid prescribing after surgical extraction of teeth in medicaid patients, 2000–2010. JAMA. 2016;315:1653. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow D., Farchione T., Sauer-Zavala S., Murray L., K, E, Bullis J., Bently K., Boettcher H., Cassiello-Robbins C. Oxford Press; New York, NY: 2018. Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Barocas J.A., Wang J., Marshall B.D.L., LaRochelle M.R., Bettano A., Bernson D., Beckwith C.G., Linas B.P., Walley A.Y. Sociodemographic factors and social determinants associated with toxicology confirmed polysubstance opioid-related deaths. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;200:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth K.S., Guille C., McCauley J., Brady K.T. Targeting practitioners: a review of guidelines, training, and policy in pain management. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173:S22–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew T.S., Tookes H.E., Bullock C., Onugha J., Forrest D.W., Feaster D.J. Examining risk behavior and syringe coverage among people who inject drugs accessing a syringe services program: a latent class analysis. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2020;78 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazazi A.R., Zelenev A., Fu J.J., Yee I., Kamarulzaman A., Altice F.L. High prevalence of non-fatal overdose among people who inject drugs in Malaysia: correlates of overdose and implications for overdose prevention from a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2015;26:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar E., Santos G.-M., Wheeler E., Rowe C., Coffin P.O. Brief overdose education is sufficient for naloxone distribution to opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A.S., Bell A., Doe-Simkins M., Elliott L., Pouget E., Davis C. From peers to lay bystanders: findings from a decade of naloxone distribution in Pittsburgh, PA. J. Psychoact. Drugs. 2018;50:240–246. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2018.1430409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicket M.C., Long J.J., Pronovost P.J., Alexander G.C., Wu C.L. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:1066–1071. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger I.A. Opioid use disorder and incarceration - hope for ensuring the continuity of treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:1193–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1900069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger I.A., Stern M.F., Deyo R.A., Heagerty P.J., Cheadle A., Elmore J.G., Koepsell T.D. Release from prison — a high risk of death for former inmates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger I.A., Blatchford P.J., Mueller S.R., Stern M.F. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;159:592–600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird S.M., McAuley A., Perry S., Hunter C. Effectiveness of Scotland’s National Naloxone Programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: a before (2006–10) versus after (2011–13) comparison. Addiction. 2016;111:883–891. doi: 10.1111/add.13265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C., Volkow N.D. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393:1760–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert A.S.B., Valenstein M., Bair M.J., Ganoczy D., McCarthy J.F., Ilgen M.A., Blow F.C. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315–1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert A.S.B., Logan J.E., Ganoczy D., Dowell D. A detailed exploration into the association of prescribed opioid dosage and overdose deaths among patients with chronic pain. Med. Care. 2016;54:435–441. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert A.S.B., Guy G.P., Losby J.L. Opioid prescribing in the United States before and after the centers for disease control and prevention’s 2016 opioid guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169:367–375. doi: 10.7326/M18-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosilkovska M., Walder B., Besson M., Daali Y., Desmeules J. Analgesics in patients with hepatic impairment: pharmacology and clinical implications. Drugs. 2012;72:1645–1669. doi: 10.2165/11635500-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boston Medical Center . 2019. BMC Office Based Addition Treatment Training and Technical Assistance (OBAT TTA)https://www.bmcobat.org/about-us/obat-tta/ [Google Scholar]

- Boston Medical Center . 2019. Massachusetts Office Based Addiction Treatment ECHO (MA OBAT ECHO)https://www.bmcobat.org/project-echo/massachusetts-obat-echo/ [Google Scholar]

- Boston Medical Center . 2019. OBAT Clinical Guidelines.https://www.bmcobat.org/resources/?category=1 [Google Scholar]

- Boston Medical Center . 2019. OBAT Clinical Tools and Forms.https://www.bmcobat.org/resources/?category=4 (Accessed September 18, 2019) [Google Scholar]

- Boston Medical Center . 2018. BMC TTA Addiction Chat Live.https://www.bmcobat.org/news/2018/09/join-our-addiction-chat-live/ [Google Scholar]

- Boston University School of Medicine . 2019. Safer/Competent Opioid Prescribing Education: SCOPE of Pain.https://www.scopeofpain.org/ (Accessed May 22, 2019) [Google Scholar]

- Bounthavong M., Devine E.B., Christopher M.L.D., Harvey M.A., Veenstra D.L., Basu A. Implementation evaluation of academic detailing on naloxone prescribing trends at the United States Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv. Res. 2019;54:1055–1064. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooklyn J.R., Sigmon S.C. Vermont hub-and-Spoke model of care for opioid use disorder: development, implementation, and impact. J. Addict. Med. 2017;11:286–292. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugal M.T., Barrio G., De L.F., Regidor E., Royuela L., Suelves J.M. Factors associated with non-fatal heroin overdose: assessing the effect of frequency and route of heroin administration. Addiction. 2002;97:319–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffington D.E., Lozicki A., Alfieri T., Bond T.C. Understanding factors that contribute to the disposal of unused opioid medication. J. Pain Res. 2019;12:725–732. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S171742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting A.M., Oser C.B., Staton M., Eddens K.S., Knudsen H. Clinician identified barriers to treatment for individuals in Appalachia with opioid use disorder following release from prison: a social ecological approach. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2018;13:23. doi: 10.1186/s13722-018-0124-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch A.E., Morasco B.J., Petry N.M. Patients undergoing substance abuse treatment and receiving financial assistance for a physical disability respond well to contingency management treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2015;58:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Assistance National Training and Technical Assistance Center . 2018. Law Enforcement Naloxone Toolkit.https://bjatta.bja.ojp.gov/tools/naloxone/Naloxone-Background [Google Scholar]

- Busch S.H., Fiellin D.A., Chawarski M.C., Owens P.H., Pantalon M.V., Hawk K., Bernstein S.L., O’Connor P.G., D’Onofrio G. Cost-effectiveness of emergency department-initiated treatment for opioid dependence. Addiction. 2017;112:2002–2010. doi: 10.1111/add.13900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C4 Innovations . 2015. Praxis: Training for MA Addiction Professionals - Opioid Overdose Prevention.https://c4innovates.com/training-technical-assistance/praxis/opioid-overdose-prevention/ [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Health Care Services . 2018. CA Bridge.https://www.bridgetotreatment.org/ (Accessed June 23, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- California Health Care Foundation . 2018. Medication-assisted Treatment in Correctional Settings.https://www.chcf.org/project/medication-assisted-treatment-in-correctional-settings/ [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C.I., Bahorik A.L., VanVeldhuisen P., Weisner C., Rubinstein A.L., Ray G.T. Use of a prescription opioid registry to examine opioid misuse and overdose in an integrated health system. Prev. Med. 2018;110:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capraro G.A., Rebola C.B. The NaloxBox program in Rhode Island: a model for community-access naloxone. Am. J. Public Health. 2018;108:1649–1651. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K. 2008. Computer-Based Training for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT4CBT)http://www.cbt4cbt.com/ (Accessed May 21, 2019) [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K.M., Weiss R.D. The role of behavioral interventions in buprenorphine maintenance treatment: a review. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2017;174:738–747. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K.M., Kiluk B.D., Nich C., Gordon M.A., Portnoy G.A., Marino D.R., Ball S.A. Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy: efficacy and durability of CBT4CBT among cocaine-dependent individuals maintained on methadone. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171:436–444. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J., Zevin B., Lum P.J. Low barrier buprenorphine treatment for persons experiencing homelessness and injecting heroin in San Francisco. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2019;14:20–29. doi: 10.1186/s13722-019-0149-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case Western University School of Medicine . 2019. Intensive Course Series on Controlled Substance Prescribing.https://cwru.cloud-cme.com/default.aspx?p=1000&search=Controlled%20Substance%20Prescribing [Google Scholar]

- Caudarella A., Dong H., Milloy M.J., Kerr T., Wood E., Hayashi K. Non-fatal overdose as a risk factor for subsequent fatal overdose among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Motivation and Change . 2014. What Is CRAFT.https://motivationandchange.com/outpatient-treatment/for-families/craft-overview/ [Google Scholar]

- Center for Motivation and Change . 2017. The 20 Minute Guide.https://the20minuteguide.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights . 2020. Staying Alive on the Outside Post-incarceration Video.https://www.prisonerhealth.org/videos-and-fact-sheets/overdose/ (Accessed June 22, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Center for Technology and Behavioral Health . 2020. Program Reviews: Synthesizing Current Research on Digital Health Technologies for Substance Use Disorders and Co-occurring Conditions.https://www.c4tbh.org/program-reviews/?f=true&category=mix&commercially_available=mix [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Application of Substance Abuse Technologies . 2019. Promoting Awareness of Motivational Incentives (PAMI)https://www.mycasat.org/courses/pami/ [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2017. Applying CDC’s Guideline for Prescribing Opioids: an Online Training Series for Healthcare Providers.https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/training/online-training.html [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2018. Evidence-based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose: What’s Working in the United States.https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-evidence-based-strategies.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2018. HIV Care Coordination Program (CCP)https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research/interventionresearch/compendium/lrc/cdc-hiv-lrc-hiv-care-coordination-program.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2019. CDC Advises Against Misapplication of the Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain.https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/s0424-advises-misapplication-guideline-prescribing-opioids.html [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2019. Information for Patients.https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/patients/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2019. Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) FAQs.https://www.cdc.gov/ssp/docs/SSP-FAQs.pdf (Accessed June 19, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. CDC Pocket Guide: Tapering Opioids for Chronic Pain.https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/Clinical_Pocket_Guide_Tapering-a.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. U.S. Opioid Prescribing Rate Maps.https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html [Google Scholar]

- Chang A.K., Bijur P.E., Esses D., Barnaby D.P., Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department. JAMA. 2017;318:1661. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A., Larochelle M.R., Xuan Z., Wang N., Bernson D., Silverstein M., Hadland S.E., Land T., Samet J.H., Walley A.Y., Bagley S.M. Non-fatal opioid-related overdoses among adolescents in Massachusetts 2012–2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J., Spence M.M., Niu F., Hui R.L., Gray P., Steinberg S. Risk of overdose with exposure to prescription opioids, benzodiazepines, and non-benzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics in adults: a retrospective cohort study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020;35:696–703. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05545-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou R., Fanciullo G.J., Fine P.G., Adler J.A., Ballantyne J.C., Davies P., Donovan M.I., Fishbain D.A., Foley K.M., Fudin J., Gilson A.M., Kelter A., Mauskop A., O’Connor P.G., Passik S.D., Pasternak G.W., Portenoy R.K., Rich B.A., Roberts R.G., Todd K.H., Miaskowski C., American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines, P Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J. Pain. 2009;10:113–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou R., Gordon D.B., de Leon-Casasola O.A., Rosenberg J.M., Bickler S., Brennan T., Carter T., Cassidy C.L., Chittenden E.H., Degenhardt E., Griffith S., Manworren R., McCarberg B., Montgomery R., Murphy J., Perkal M.F., Suresh S., Sluka K., Strassels S., Thirlby R., Viscusi E., Walco G.A., Warner L., Weisman S.J., Wu C.L. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American pain society, the American society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine, and the American society of anesthesiologists’ committee on regional anesthesia, executive committee, and administrative council. J. Pain. 2016;17:131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou R., Korthuis P., Weimer M., Bougatsos C., Blazina I., Zakher B., Grusing S., Devine B., McCarty D. Medication-assisted treatment models of care for opioid use disorder in primary care settings. AHRQ Technical. 2016 Brief No. 28https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/opioid-use-disorder_technical-brief.pdf(Accessed May 21, 2019) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen D.R., Landes R.D., Jackson L., Marsch L.A., Mancino M.J., Chopra M.P., Bickel W.K. Adding an Internet-delivered treatment to an efficacious treatment package for opioid dependence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014;82:964–972. doi: 10.1037/a0037496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysalis House Inc . 2019. Chrysalis House: Treatment for Women With Substance Use Disorders.http://www.chrysalishouseInc.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Clark L., Haram E., Johnson K., Molfenter T. 2010. Getting Started With Medication-assisted Treatment: With Lessons From Advancing Recovery.http://www.niatx.net/PDF/NIATx-MAT-Toolkit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Clark A.K., Wilder C.M., Winstanley E.L. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J. Addict. Med. 2014;8:153–163. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe M.A., Walsh S.L. Distribution of naloxone for overdose prevention to chronic pain patients. Prev. Med. 2015;80:41–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin P.O., Sullivan S.D. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;158:1–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin P.O., Behar E., Rowe C., Santos G.M., Coffa D., Bald M., Vittinghoff E. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016;165:245–252. doi: 10.7326/M15-2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Medicine: University of Massachusetts Medical School . 2018. Naloxone Information and Resources.https://commed.umassmed.edu/naloxone [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts . 2020. Massachusetts Prescription Awareness Tool (MassPAT)https://www.mass.gov/guides/massachusetts-prescription-awareness-tool-masspat [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C., Lum P. 2017. Integrating Buprenorphine Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care.https://ciswh.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Buprenorphine-Implementation-Manual-for-Primary-Care-Settings-.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cushman P.A., Liebschutz J.M., Anderson B.J., Moreau M.R., Stein M.D. Buprenorphine initiation and linkage to outpatient buprenorphine do not reduce frequency of injection opiate use following hospitalization. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2016;68:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G., O’Connor P.G., Pantalon M.V., Chawarski M.C., Busch S.H., Owens P.H., Bernstein S.L., Fiellin D.A. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:1636–1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S., Mills K.L., Ross J., Teesson M. Rates and correlates of mortality amongst heroin users: findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS), 2001–2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N., Funk M.J., Proescholdbell S., Hirsch A., Ribisl K.M., Marshall S. Cohort study of the impact of high-dose opioid analgesics on overdose mortality. Pain Med. 2016;17:85–98. doi: 10.1111/pme.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C., Carr D. State legal innovations to encourage naloxone dispensing. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2017;57:S180–S184. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C.S., Ruiz S., Glynn P., Picariello G., Walley A.Y. Expanded access to naloxone among firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical technicians in Massachusetts. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:e7–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C.S., Southwell J.K., Niehaus V.R., Walley A.Y., Dailey M.W. Emergency medical services naloxone access: a national systematic legal review. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2014;21:1173–1177. doi: 10.1111/acem.12485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C.S., Carr D., Southwell J.K., Beletsky L. Engaging law enforcement in overdose reversal initiatives: authorization and liability for naloxone administration. Am. J. Public Health. 2015;105:1530–1537. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Crescenzo F., Ciabattini M., D’Alò G.L., De Giorgi R., Del Giovane C., Cassar C., Janiri L., Clark N., Ostacher M.J., Cipriani A. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychosocial interventions for individuals with cocaine and amphetamine addiction: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer K., Saunders B., Strang J. Take home naloxone and the prevention of deaths from opiate overdose: two pilot schemes. BMJ. 2001;322:895–896. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7291.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doctor J.N., Nguyen A., Lev R., Lucas J., Knight T., Zhao H., Menchine M. Opioid prescribing decreases after learning of a patient’s fatal overdose. Science. 2018;361:588–590. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe-Simkins M., Quinn E., Xuan Z., Sorensen-Alawad A., Hackman H., Ozonoff A., Walley A.Y. Overdose rescues by trained and untrained participants and change in opioid use among substance-using participants in overdose education and naloxone distribution programs: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:297. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donofrio G., Degutis L.C. Integrating project ASSERT: a screening, intervention, and referral to treatment program for unhealthy alcohol and drug use into an urban emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2010;17:903–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran K.M., Rahai N., McCormack R.P., Milian J., Shelley D., Rotrosen J., Gelberg L. Substance use and homelessness among emergency department patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell D., Haegerich T., Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2016:65. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dr. Robert Bree Collaborative, Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group . 2017. Dental Guideline on Prescribing Opioids for Acute Pain Management.http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/20171026FINALDentalOpioidRecommendations_Web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dr. Robert Bree Collaborative, Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group . 2018. Prescribing Opioids for Postoperative Pain – Supplemental Guidance.http://agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/FinalSupBreeAMDGPostopPain091318wcover.pdf [Google Scholar]