Abstract

Coronaviruses have caused serious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreaks, and only remdesivir has been recently indicated for the treatment of COVID-19. In the line of therapeutic options for SARS and MERS, this study aims to summarize the current clinical evidence of treatment options for COVID-19. In general, the combination of antibiotics, ribavirin, and corticosteroids was considered as a standard treatment for patients with SARS. The addition of this conventional treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir, interferon, and convalescent plasma showed potential clinical improvement. For patients with MERS, ribavirin, lopinavir/ritonavir, interferon, and convalescent plasma were continuously recommended. However, a high-dose of corticosteroid was suggested for severe cases only. The use of lopinavir/ritonavir and convalescent plasma was commonly reported. There was limited evidence for the effect of corticosteroids, other antiviral drugs like ribavirin, and favipiravir. Monoclonal antibody of tocilizumab and antimalarial agents of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine were also introduced. Among antibiotics for infection therapy, azithromycin was suggested. In conclusion, this study showed the up-to-date evidence of treatment options for COVID-19 that is helpful for the therapy selection and the development of further guidelines and recommendations. Updates of on-going clinical trials and observational studies may confirm the current findings.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS, MERS, Treatment, Evidence-based medicine

Introduction

The outbreak of new coronavirus (as termed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2]) has posed a threatened condition for global health. Since the first case was reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019, it has spread to 215 countries all over the world with more than one million cases and 56,986 deaths by April 4, 2020. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is speedily expanded, and flows of investigations are tensely ongoing. Sanders et al. has reported a comprehensive review of repurposed and investigational drugs as well as adjunctive therapies for the treatment of COVID-19 [1]. The interim guidelines on antiviral therapy for COVID-19 have been also recently published [2]. Given that not all of the drugs that have in vitro and in vivo are benefit on humans [3], we take our focus on clinical evidence only. Additionally, since the increasing number of publications regarding COVID-19, new updates are required for appropriate information. In particular, remdesivir has been recently approved for the treatment of COVID-19 in many countries. The reminder of adverse events for treatment of antimalarial drugs was also covered in our study [4]. Furthermore, for studies that examined the effect of the same treatment on the same disease outcome, we applied a random-effects model to obtain the pooled estimate of the association. Therefore, in this review, we highlighted some of the latest information of SARS-CoV-2, compared to that of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and SARS-CoV, and provided recommendations for COVID-19 management from multiple points of view.

Virology

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) belongs to the subgenus sarbecovirus of betacoronavirus. Full-genome sequencing and phylogenetic profiling analysis revealed that shared 79.6% and 50% sequence identity to 2 types of human coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV respectively [5]. Notably, it is highly similar to bat corona virus (BatCoV) RaTG13 with 96.1% sharing genome sequence identity [6]. This finding suggested that bats are likely the primary source of the COVID-19 virus. On the other hand, given the fact that the structure of the receptor-binding domain of S protein of 2019-nCoV is 99% similar to that of coronavirus isolated from pangolin, it is hypothesized that pangolin is also possible reservoir hosts of SARS-CoV-2 [7].

The SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to use angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as functional receptors for cell entry [6]. This is relatively similar to previous findings of the way SARS-CoV attack the human body [8]. Moreover, recent studies have found that the modified S protein of SARS-CoV-2 has a significantly higher affinity for ACE2 and is 10- to 20-fold more likely to bind to ACE2 in human cells than the S protein of the previous SARS-CoV [9]. This higher affinity may give the easier human-to-human spread of the virus and consequently contribute to a higher estimated transmission rate (R0) for SARS-CoV-2 than the previous SARS virus. The Ro of SAR-CoV-2 is between 1.4 and 2.5, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) statement [10] and between 2.24 and 3.58 in other research. For comparison, the R0 for SARS is 1.3 and that of MERS was 2 in the early stage of pandemics.

A recent genetic analysis of 103 SARS-CoV-2 genomes revealed that there are two major types of viruses, namely L and S [11]. The L type, which might be more aggressive, is accounted for 70% and the percentage of S type, considered as an ancestral and less aggressive version, is 30%. The research also suggested that human intervention may affect virus evolution and emphasized the need for more comprehensive data of genomes sequences and clinical characteristics.

Clinical features

1. Incubation

The incubation period for SAR-CoV is thought to be between 2 - 10 days [12] and for MERS-CoV is typically approximately 5 days (range 2 - 14 days) [13]. The median incubation period of COVID-19 was estimated to be within a range of 2 – 14 days, though it might be extended by 24 days [14]. It is concerned that the longer time of incubation may lead to a high rate of asymptomatic and may also facilitate the spread of infection. On the other hand, shorter incubation periods have associated with greater severity as well as a higher risk of death in coronavirus infections [15,16]. However, no statistically significant difference is founded in incubation times amongst SARS‐CoV‐2, SARS‐CoV, and MERS‐CoV mainly because of the limitation of available data [17].

2. Presentation

It was stated that many cases are likely asymptomatic, and the presentation of symptoms has a varied spectrum from mild to extremely severe [18]. The largest cohort of more than 44,000 persons with COVID-19 from China indicated that the degree of illness can range from mild to critical [19]. The rates for mild to moderate and severe are 81% and 14% respectively [19]. Critical symptoms including respiratory failure, shock, or multi-organ system dysfunction accounted for 5% and about 49% of these critical cases lead to death [19].

Fever and cough were the most common symptoms whereas gastrointestinal symptoms and headache are less presented [20]. Similar findings were confirmed by an analysis of 1,099 laboratory-confirmed cases, which showed that fever was observed in 87.9% of cases and cough in 67.7% [21]. In severe and critical cases, patients with SARS-CoV-2 may develop acute respiratory distress syndromes with cytokine storms and become worsen in a short period [22]. These would lead to multiple organ failure and death without appropriate intervention [23].

The current case fatal rate (CFR) for COVID-19 is 2.6% base on a summary report from more than 72,528 confirmed cases in China [23] and is 3.4% according to the announcement of WHO in March 2020 [24]. Even though this number is lower than that of SARS and MERS, which are 9.6% and 34.4%, respectively, COVID-19 still has caused more total deaths due to the emerging number of cases. Severe illness and the poor outcome can occur in any health condition of any age, but it is mainly associated with old age or underlying medical co-morbidities, including, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic lung disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease.

Treatment options for SARS-CoV infection

Stockman et al. systematically reviewed the effect of anti-viral agents, corticosteroids, interferon (IFN) type I, and convalescent plasma or immunoglobulin [25]. However, the efficacy and safety of agents have been controversial. While some individual studies reported possible harmful effects, the others have still been inconclusive. In the current study, we shifted our interest into the treatment plan for patients who were hospitalized and diagnosed with SARS.

Ribavirin which is a guanosine analogue has been demonstrated to have antiviral activity against a broad range of DNA and RNA viruses [26]. In clinical practice, it has been mostly used in the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection, chronic hepatitis C infection, viral hemorrhagic fevers, and several other severe and life-threatening viral infections [26]. In a prospective cohort study on the Hong Kong population, initial SARS patients were given antibiotics for pneumonia and oseltamivir for influenza infection [27]. If the fever remained after 2 days from hospitalization, patients were given ribavirin in the combination with a low dose of prednisolone or hydrocortisone. High dose of methylprednisolone for 3 consecutive doses up to 6 doses were given after day 3 - 4 if fever persisted or lung shadow increased. Ribavirin and a low dose of corticosteroid were continuously given up to a max of 12 days until the resolution of lung opacity was completed. The combination of broad-spectrum antibiotics, ribavirin, and corticosteroids was also used to treat patients in other observational studies [28,29].

In clinical practice, it might be difficult to distinguish patients with SARS infection and non-SARS community-acquired pneumonia, suspected SARS cases were normally initiated to be given antibiotics to support the confirmation of SARS cases with non-response to the antibiotic therapy, and to ensure the completed eradication of any bacteria [30,31]. Empirical therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics such as fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin) and macrolides (azithromycin [AZM] or clarithromycin) were recommended [30,31]. Antibiotics could be used for a longer duration of two to six days to follow the effect on the overall clinical improvement, fever, or radiographic evidence of disease and confirm there was no evidence of pneumonia infection detected by serologic analysis and urinary antigen detection [32,33]. Antibiotics could be also given until there was a confirmed diagnosis of SARS or during the 14-day treatment course [29]. Ribavirin was offered at the dose of 8 mg/kg every 8 hours for intravenous route or 1.2 g every 8 hours by oral [32]. While intravenous corticosteroids with a normal dose (hydrocortisone 4 mg/kg daily, or 200 mg every 8 h for 10 days) were followed by oral corticosteroids with a decreasing maintenance dose (methyl prednisolone 240 to 320 mg daily, or prednisolone 1 mg/kg for 5 days, 0.5 mg/kg for 3 days, and 0.25 mg/kg for 3 days) in most of the studies [28,33], the reverse order was provided in a prospective study of 138 patients [27]. A recent meta-analysis of 13 trials reported that corticosteroids significantly decreased the mortality risk by 42% among patients with severe pneumonia (RR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.40 - 0.84), but not among patients without severe pneumonia (RR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.45 - 2.00) [34]. However, overall mortality reduction was not achieved for adjunct corticosteroid among patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia in a meta-analysis using individual patient data [35]. Given that the efficacy data for the comparison effect between intervention and control groups was unavailable, corticosteroids were not routinely given together with ribavirin in a retrospective study of 229 Singapore SARS cases [36]. Administering ribavirin was observed to be not associated with the risk of death (RR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.44 - 2.42), after adjusting for sex, age, lactate dehydrogenase, corticosteroid and antibiotic use [36].

It was reported in the WHO meeting that an anti-HIV drug named lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) could have the mortality risk reduction among patients with SARS. There were no deaths among 34 patients who received LPV/r combined with ribavirin, whereas 10% of 690 patients who received ribavirin alone had died at the 30 days from the onset of symptoms [37]. However, the mortality rate was not significantly different between two groups (P = 0.052). In another retrospective matched cohort study of Hong Kong SARS patients, the standard treatment of ribavirin and corticosteroid was provided to patients at the initial time of SARS confirmation [38]. LPV/r (lopinavir 400mg and ritonavir 100 mg every 12 hours) was added to standard treatment as initial therapy, or it was given without ribavirin as a rescue therapy [38]. Combination with LPV/r as the initial therapy significantly reduced the mortality on day 21, compared with ribavirin and corticosteroids alone (1/44 death in LPV/r arm and 99/634 deaths in the control arm, P <0.05) [38]. A similar treatment plan was conducted in another retrospective study of 152 patients [39]. The risk of acute respiratory stress syndrome or death was significantly lower in LPV/r group than control group (2.4% vs. 28.8%, P <0.05) [39].

Interferons (IFNs) have been known as important glycoprotein that can inhibit viral replication [40]. In an open-label study of 22 SARS patients, oral prednisone 50 mg or intravenous methylprednisolone 40 mg was given every 12 hours [41]. IFN alfa-1 was provided with an increasing dose from 9 μg/d to 15 9 μg/d during 2 to 10 days of the treatment [42]. A combination of IFN alfa-1 and corticosteroid significantly decreased disease-related impaired oxygen saturation and creatinine kinase levels, compared with corticosteroid alone [42].

A retrospective study reported the effect of convalescent plasma in 80 SARS patients [43]. Patients were given convalescent at the volume of 279.3 ml (range, 160 – 640 ml), which is similar to the volume giving to patients with Ebola hemorrhagic fever [43]. The treatment with convalescent plasma plus methylprednisolone before day 14 showed a better outcome than those given after day 14 (58.3% vs. 15.6%, P <0.001) but the mortality was comparable (6.3% vs. 21.9%, P = 0.08) [43]. In another retrospective study, the discharge rate by day 22 in patients treated with convalescent plasma at the volume of 200 – 400 ml significantly higher than those treated with corticosteroids (77.8% vs. 23%, P = 0.004) [44]. Furthermore, immunoglobulin also had potential treatment effects in severe SARS patients in some studies [45,46].

Treatment options for MERS-CoV infection

Given the effectiveness of agents that were used in the treatment of SARS, Momattin et al. suggested the therapeutic schedule for oral ribavirin, LPN/r, peginterferon alfa-2a, and convalescent plasma as possible therapies for patients diagnosed with MERS [47]. Ribavirin was suggested with the dose adjustment (2,000 mg loading dose then 1,200 mg every 8 hours for 4 days, then 600 mg every 8 hours for 4 - 6 days) [47] but the doses were still higher than those given to SARS patients. A similar treatment schedule with SARS for LPV/r (lopinavir 400 mg/ ritonavir 100 mg twice daily for 10 days) with or without ribavirin was proposed [47]. According to the guidance of the Korean Society of Infectious Disease and Korean Society for Antimicrobial Therapy, antiviral drugs were recommended to be administered as soon as possible for 10 to 14 days [48]. Additionally, pegylated IFN alfa-2a 1.5 μg/kg once per week for 2 weeks was considered to administer MERS patients [47]. The combination of ribavirin and IFN was often observed in retrospective studies [49,50]. In a cohort study of 44 Saudi Arabia patients, the survival rate after 14 days in the intervention group (oral ribavirin for 8 - 10 days and subcutaneous pegylated IFN alfa-2a 180 μg per week for 2 weeks) was significantly higher than the comparison group (70% vs. 29%, P = 0.004), but no change after 28 days [49]. The mortality in patients treated with IFN alfa-2a and those treated with IFN beta-1a was comparable (85% vs. 64%, P = 0.24) [50]. Furthermore, convalescent plasma 300 - 500 ml could be given to patients with severe MERS infection that was refractory to antiviral drugs [47,48]. Moreover, high-dose methylprednisolone could be used when the fever persisted, respiratory failure or radiological findings worsened and a step-down dosing schedule was recommended [48].

Current evidence for COVID-19 treatment options

In the line of therapeutic options for SARS and MERS infections, we summarized current evidence of the above-mentioned drugs in the treatment of COVID-19 and discussed the recently recommended treatments.

1. Ribavirin and interferon

Although ribavirin and IFN alfa had been widely used in the outbreak of SASR in Hong Kong, the appropriate dose of ribavirin was recommended to be considered carefully because of its hematologic toxicity [51]. The combination of ribavirin and IFN in an observational study of 349 patients with MERS did not significantly reduce the mortality on day 90 (HR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.73 - 1.44) or enhance MERS clearance (HR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.30 - 1.44) [52,53]. However, intravenous ribavirin 500 mg 2 - 3 times daily and inhaled IFN alfa 5 million U was still suggested as one of the standard treatments according to Chinese guidelines [17,53]. Nevertheless, ribavirin and IFN alfa were not mentioned in other institutional guidelines.

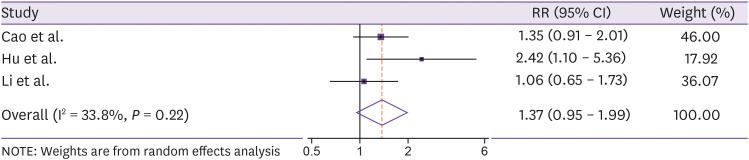

However, findings from a recent multicenter randomized trial in Hong Kong reported that combination of ribavirin 400 mg every 12 h, three doses of 8 million units of IFN beta-1, and LPV/r 400/100 mg was observed to have shorter duration of viral shedding (HR = 4.37, 95% CI = 1.86 - 10.24) and hospital stay (HR = 2.72, 95% CI = 1.20 - 6.13) than the treatment with LPV/r alone [54]. Additionally, adverse events including nausea, diarrhea, increased alanine aminotransferase, hyperbilirubinaemia, sinus bradycardia, and fever were not significantly different between two groups (P >0.05) [54]. However, our pooled estimates of three individual studies [55,56,57] did not find the significant improvement of clinical outcomes among patients treated with LPV/r (pooled RR = 1.37, 95% CI = 0.95 – 1.99, Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Meta-analysis of the association between lopinavir/ritonavir and clinical improvement in COVID-19 patients.

2. Remdesivir

Remdesivir is another anti-hepatitis C virus drug-like ribavirin that can bind to COVID-19 RNA dependent RNA polymerase [58]. It was used in the treatment of the first COVID-19 patient in the United States (US) [51,59]. Intravenous remdesivir was given from day 7 and no adverse reactions were associated with the infusion [59]. Remdesivir was initially used in the treatment for the other three patients during 4 - 10 days until the respiratory symptoms were improved [60]. However, the efficacy and safety of remdesivir have not been confirmed because there was no comparison group and the treatment response might be affected by the probable presence of unmeasured confounding factors such as corticosteroids [60]. Findings from a recent randomized controlled trial of 237 patients from ten centers in China (April 30, 2020) reported remdesivir had no clinical improvement (HR = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.87 - 1.75) than placebo [61]. However, the finding suggested the potential effect of remdesivir vs. placebo among those treated within 10 days of symptoms [61]. Additionally, preliminary data from 1,063 patients participating in the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (April 29, 2020), which was launched by the National Institute Allergy and Infectious Disease in the US, showed that the time to recovery in patients received remdesivir was significantly 31% faster than those received placebo (P <0.001) [62]. The mortality rate in the remdesivir group was 11.6%, compared with 8.0% in the placebo group (P = 0.059) [62]. Consideration of the scientific evidence of efficacy and safety, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization for intravenous remdesivir in the treatment of severe patients in the US since May 1, 2020.

3. Lopinavir/ritonavir

The combination of anti-human immunodeficiency virus drugs - lopinavir and ritonavir - and ribavirin has shown to have some activities against SARS and MERS and become one of the potential therapies for the treatment of COVID-19 [51]. It was reported that the third COVID-19 case of Korea was received LPV/r 400/100 mg twice daily from day 10 to day 19 and the viral load decrease was observed from day 11 [63]. Another case report from China revealed that the addition of LPV/r 800/200 mg daily might be related to the improvement of clinical symptoms after failing with methylprednisolone and IFN therapies [64]. In a report of 18 Singapore cases, five patients were administered LPV/r 400/100 mg twice daily and two of them obtained the viral shedding within 2 days of the treatment [65]. However, only one patient completed the 14-day treatment course due to the progression of adverse events [65].

Recently, Cao et al. conducted a randomized open-label trial of 199 hospitalized patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 to compare the efficacy and safety of oral LPV/r 400/100 mg twice daily plus standard of care vs. standard of care alone [55]. The treatment with LPV/r for 14 days did not show any differences in terms of time to clinical improvement (HR = 1.24, 95% CI = 0.90 - 1.72), but it was 1 day shorter in the LPV/r group (HR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.00 - 1.91) in the modified intention-to-treat analysis [55]. The 28-day mortality was not significantly different between groups (19.2% for LPV/r group vs. 25.0% for control group, P = 0.32) [55]. Despite non-significant findings from the trial, LPV/r is expected to be more effective in patients with COVID-19 [66]. This point was explained by the inclusion of patients with severe infection and substantial tissue damage in the trial, thus, the effect of LPV/r might be higher in the early stage of the disease [66]. Besides, the lack of evidence of drug pharmacokinetic where the virus is replicating did not allow us to know whether LPV/r concentration was high enough to inhibit the viral replication [66].

Data from a retrospective study of 298 Chinese patients showed that the number of patients treated with LPN/r was not different between severe and non-severe patients (84.5% vs. 77.9%, P = 0.288) [67]. In another retrospective study of 323 patients in Wuhan, LPN/r was more given to critical patients (46.2%) than non-critical cases (5.4%) and more administered in unfavorable than favorable outcomes (23.8% vs. 5.0%) [56]. Furthermore, treatment with LPN/r was reported to be independently associated with the prolongation of virial RNA shedding (OR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.10 - 5.36) and earlier provided LPN/r might shorten the viral shedding as well (22 days vs. 28.5 days, P = 0.02) [68]. Findings from the efficacy of lopinavir plus ritonavir and arbidol against novel coronavirus infection (ELACOI) trial also suggested the little benefit improvement of LPV/r in clinical outcomes among non-severe patients, compared with supportive care [57].

LPV/r is recommended at the dose of 400/100 mg twice daily with the administration duration of 5 - 10 days by the Nebraska Medicine and considered as one of the standard treatments according to Chinese guidelines. However, recent report recommended against the use of LPN/r in the treatment of COVID-19, except for the purpose of clinical trial due to the consideration of required dose and non-significant findings from current small trials [69].

Antiviral therapies might be timely given to patients with COVID-19. An observational study of 280 cases showed that patients in the mild group were more likely to be received antiviral therapies of ribavirin and LPV/r earlier than those in the severe group (1.19 ± 0.45 vs. 2.65 ± 1.06 days, P <0.001) [70]. Additionally, time from disease onset to antiviral therapy was positively correlated with the time to disease recovery (r = 0.785, P <0.001) [70].

4. Arbidol

In the ELACOI trial, arbidol monotherapy was suggested for the potentially clinical benefit compared with supportive care among patients with the mild or moderate disease [57]. Findings from a retrospective study of 50 patients revealed that arbidol monotherapy might be superior than LPN/r in terms of viral load on day 14 (0.0% in the arbidol group vs. 44.1% in the LPN/r group) and duration of positive RNA test (9.5 days in the arbidol group vs. 11.5 days in the LPN/r group, P <0.01) [71]. Deng et al. reported that the combination of arbidol and LPN/r was associated with an elevated negative conversion rate of the viral test on day 7 (75% vs. 35%, P <0.05) and day 14 (94% vs. 53%, P <0.05) and an improvement of the chest X-rays on day 7 (69% vs. 29%, P <0.05), compared with LPN/r alone [72].

5. Favipiravir

Two recently open-label trials reported findings for the effect of favipiravir on the treatment of COVID-19 [73,74]. In the non-randomized trial of 80 patients in China, favipiravir was found to significantly reduce the viral clearance time (4 vs. 11 days, P <0.001), increase the improvement rate (32/35 vs. 28/45, P = 0.004) for chest imaging with the lower adverse events than LPV/r (4/35 vs. 25/45, P <0.01) [73]. Another randomized trial of 240 patients reported that favipiravir significantly increased the 7-day clinical recovery rate compared with arbidol (70/98 vs. 62/111, P = 0.02) among subgroup of COVID-19 patients without hypertension and diabetes [74]. Favipiravir was also considered for the treatment of COVID-19 by the Japan government.

6. Corticosteroids

Regarding the use of corticosteroids for COVID-19 pneumonia, the Chinese Thoracic Society suggested the low-to-moderate dose of methylprednisolone ≤0.5 - 1 mg/kg per day or equivalent for no more than one week [75]. In contrast, considering the clinical evidence of the possible harmful effect over the benefit of corticosteroids in SARS, MERS, and influenza patients, Russell et al. recommended not to use corticosteroids for the treatment of COVID-19-induced lung injury or shock [76]. However, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine suggested low-dose therapy of intravenous hydrocortisone 200 mg per day for COVID-19 patients with refractory shock [77]. The suggestion was indirectly generalized from a meta-analysis of 22 randomized clinical trials with 7,279 participants for the effect of low dose corticosteroids in patients with septic shock. Although corticosteroids were not significantly associated with either short-term mortality (RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.91 - 1.02) or long-term mortality (RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.90 - 1.02), there were significant shock resolution time, mechanical ventilation, and intensive care unit stay reductions among adults treated with low dose corticosteroids (P <0.0001) [77,78].

The interim guidance of the WHO for the clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection with the suspect of COVID-19 recommended not indicating corticosteroids routinely unless indicated for another reason. This recommendation was raised based on findings from a multicenter study of 309 MERS patients [79]. The 90-day mortality was not significantly different between corticosteroid therapy and control group (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.52 - 1.07) despite the significant virus RNA clearance (HR = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.17 - 0.72) [79]. However, retrospective data from 298 cases in China showed the significantly higher patients treated with corticosteroids in the severity group than the non-severity group (84.5% vs. 17.5%, P <0.001). This might raise the consideration of disease severity among corticosteroid-treated patients [67].

7. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and azithromycin

Antimalarial drugs including chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) have been reported for their antiviral activities against SARS and COVID-19 in-vitro [80]. Cortegiani et al. recently systematically reviewed for current evidence and did not find any clinical data for the efficacy and safety of chloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 [81]. However, the Dutch Center of Disease Control suggested giving chloroquine for adults with severe infection at the dose of 600 mg base, followed by 300 mg after 12 hours on day 1, and 300 mg twice daily from days 2 – 5 [81]. The Italian Society of Infectious and Tropical disease suggested the administration of chloroquine 500 mg twice daily for 10 days [81].

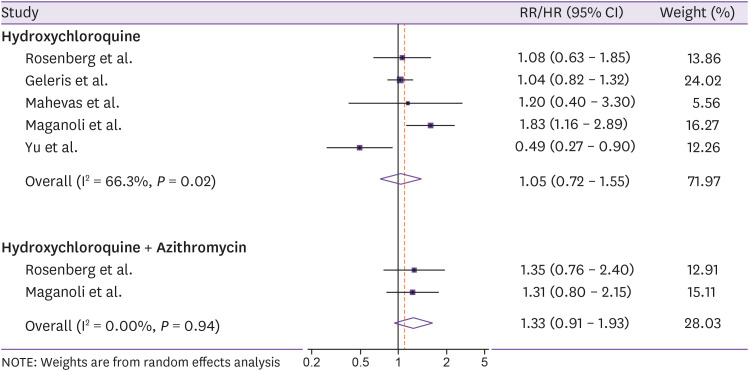

Million et al. reported outcomes from 1,061 French patients receiving HCQ 200 mg three times per day for 10 days in combination with AZM 500 mg daily on day 1 and 250 mg daily for the next 4 days [82]. Administration of HCQ and AZM before complications was safe with 2.4% patients with treatment-related adverse events and the mortality rate of 0.8% [82]. Another retrospective study of 1,438 hospitalized patients in 25 hospitals showed that HCQ alone, AZM alone, and HCQ in combination with AZM did not reduce the mortality, with HRs (95% CIs) of 1.08 (0.63 - 1.85), 0.56 (0.26 - 1.21), and 1.35 (0.76 - 2.40), respectively [83]. Similar findings from a study of 1,376 hospitalized patients in New York were reported, with no association between HCQ administration (600 mg twice on day 1 and 400 mg daily for the next 4 days) and the risk of intubation or death (HR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.82 - 1.32) [84]. Furthermore, routine care data of 181 patients in four French care centers found no effect of HCQ 600 mg/day for 2 days on overall survival (HR = 1.20, 95% CI = 0.40 - 3.30) [85]. In contrast, findings from a retrospective study of 807 patients found that treatment with HCQ was associated with an 83% increased risk of death (HR = 1.83, 95% CI = 1.16 - 2.89), compared with non-HCQ treatment group, whereas the result for the combination of HCQ and AZM remained non-significant (HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 0.80 - 2.15) [86]. However, a significantly higher mortality (18.8% vs. 47.4%, P <0.001) but longer hospitalized duration (15 vs. 8, P <0.05) in patients treated with low dose of HCQ (200 mg twice daily for 7 - 10 days), compared with those who did not, was reported in another retrospective study of 550 Chinese patients [87]. Our pooled estimates of five individual studies [83,84,85,86,87] showed that both HCQ and HCQ combined with AZM did not reduce the risk of mortality, with pooled RRs/HRs (95% CIs) of 1.05 (0.72 - 1.55) and 1.33 (0.91 - 1.93), respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of hydroxychloroquine and hydroxychloroquine combined with azithromycin in relation to the risk of mortality in COVID-19 patients.

A pilot randomized trial enrolled 30 treatment-naïve COVID-19 patients in China and compared the effect of HCQ 400 mg daily for 5 days plus standard of care with the standard of care alone [88]. Preliminary results showed that the negative conversion rate of COVID-19 in swabs, time to virus nucleic acid negative conversion, time to body temperature normalization, radiological progression, and adverse events were comparable between groups (P >0.05) [88]. Another open-label clinical trial of 36 France patients investigated the effect of HCQ 200 mg every 8 hours [89]. It was reported that the day-6 viral cure in HCQ group was significantly higher than the control group (14/20 vs. 2/16, P = 0.001) [89]. Additionally, in the subgroup analysis of patients receiving HCQ, AZM 500 mg on day 1, followed by 250 mg from days 2 - 5 significantly enhanced the effect of HCQ on virus elimination (6/6 vs. 8/14) [89]. The pooled analysis from these studies indicated the non-significant difference between HCQ treatment and the control group in terms of virological cure, death or clinical worsening, and safety, but the lower risk of lung disease progression was observed (OR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.11 - 0.90) [90]. Furthermore, findings from a randomized trial of 62 Chinese patients showed that the addition of HCQ 400 mg/day for 5 days significantly shorten the body temperature recovery time (2.2 days vs. 3.2 days, P = 0.001) and the cough remission (2.0 days vs. 3.1 days, P = 0.002) and improved the pneumonia condition (80.6% vs. 54.8%) [91].

Despite the potential treatment effect, the European Medicines Agency has recently concerned the drug adverse reaction of chloroquine and HCQ on the cardiac, including cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and QT prolongtation [4,92]. Chloroquine, HCQ, and AZM were hypothesized to be able to block the sodium channel that might lead to proarrhythmia and heart failure in COVID-19 patients with myocardial injury and hypoxia [93]. Neuropsychiatric and hepatic disorders such as agitation, insomnia, confusion, psychosis and suicidal ideation, seizures, and blood glucose lowering were observed among patients treated with chloroquine and HCQ [93]. The cardiac arrest among patients treated with HCQ in combination with AZM were observed to be significantly higher than those who received neither drug (OR = 2.13, 95% CI = 1.12 - 4.05) [83]. Additionally, treatment with HCQ, with or without AZM was associated with a risk of hospitalized prolongation [86]. Hence, several clinical trials have been also suspended or stopped in some European countries [4].

8. Convalescent plasma

A meta-analysis of 32 studies showed that convalescent plasma might reduce the mortality rate among patients with coronavirus infection and severe influenza (OR = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.14 - 0.25) [94]. During the outbreak of COVID-19, Shen et al. reported a case series of 5 patients, who were administered 400 ml convalescent plasma between day 10 and day 22 from hospitalization [95]. After the transfusion, viral loads were observed to decrease and be negative and there was an increase of COVID-19-specific antibody [95]. Despite some critical issues, the approach was expected to have the potential utility of passive antibody treatment, especially in the high-risk population [96].

According to the recent report on April 3, 2020, the status of some Korean patients with pneumonia treated with convalescent plasma was confirmed to be improved, such as the decrease of the inflammatory index. Among 19 patients treated with convalescent plasma in Severance Hospital, the clinical outcomes were described for two cases of severe pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome [97]. The administration of convalescent plasma after systemic therapies of LPN/r and HCQ performed the improvement of oxygenation and chest X-rays, and the decrease of inflammatory markers and viral loads [97]. It was suggested by the Korean Association of Internal Medicine that convalescent plasma in the combination with other supportive care had a significant effect on mortality reduction among serious cases among 3.8% MERS patients treated with convalescent plasma. The guidelines for using convalescent plasma for serious cases are being developed by The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with the consults with several experts, including the Korean Society of Blood Transfusion.

9. Protective monoclonal antibody

Recently, tocilizumab, an immunosuppressive drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis has become a promising candidate for COVID-19 treatment. Studies have indicated that there is an association between interleukin (IL)-6 levels and the severity of COVID-19. Though not any clinical study has proved the effects of tocilizumab on COVID-19, this IL-6 receptor blockage might improve the mortality rate in the subgroup patients with cytokine storm syndromes [98]. This is the first drug entered the phase III clinical trial approved by the Food Drug Administration to treat COVID-19 patients. Findings from a study of 20 patients with COVID-19 reported that the combination of tocilizumab and standard of care improved some clinical outcomes such as fever disappearance within a few days, oxygen intake lowering requirement (75.0%), lung opacity absorption (90.5%), lymphocytes increase, and C-reactive protein decrease [99]. However, the effect of tocilizumab was not confirmed because of the lack of the comparison group [99]. Another IL-6 antibody, sarilumab has also gone ahead for a clinical study in severe COVID-19 patients. Given the fact that pulmonary edema caused by exudative inflammation is particular feature of COVID-19 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a potential factor that induces vascular permeability [100], it is suggested that anti-VEGF (bevacizumab) could be a potential drug for treating COVID-19 patients with severe and critical conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study summarized the up-to-date evidence of treatment options for COVID-19 that is helpful for the therapy selection and the development of further guidelines and recommendations. Updates from thousands of on-going clinical trials and observational studies may confirm the current findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

T.H. received supports from the National Cancer Center, Korea (1910330).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest.

- Conceptualization: TH, TTAT.

- Data curation: TH, TTAT.

- Methodology: TH, TTAT.

- Writing - original draft: TH, TTAT.

- Writing - review & editing: TH, TTAT.

References

- 1.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SB, Huh K, Heo JY, Joo EJ, Kim YJ, Choi WS, Kim YJ, Seo YB, Yoon YK, Ku NS, Jeong SJ, Kim SH, Peck KR, Yeom JS. Interim guidelines on antiviral therapy for COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020;52:281–304. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JP, Rees S, Kalindjian SB, Philpott KL. Principles of early drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1239–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Medicines Agency. COVID-19: reminder of the risks of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. [Accessed 14 June 2020]. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/covid-19-reminder-risks-chloroquine-hydroxychloroquine.

- 5.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, Bi Y, Ma X, Zhan F, Wang L, Hu T, Zhou H, Hu Z, Zhou W, Zhao L, Chen J, Meng Y, Wang J, Lin Y, Yuan J, Xie Z, Ma J, Liu WJ, Wang D, Xu W, Holmes EC, Gao GF, Wu G, Chen W, Shi W, Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao K, Zhai J, Feng Y, Zhou N, Zhang X, Zou JJ, Li N, Guo Y, Li X, Shen X, Zhang Z, Shu F, Huang W, Li Y, Zhang Z, Chen RA, Wu YJ, Peng SM, Huang M, Xie WJ, Cai QH, Hou FH, Liu Y, Chen W, Xiao L, Shen Y. Isolation and characterization of 2019-nCoV-like coronavirus from Malayan Pangolins. bioRxiv. 2020 [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greenough TC, Choe H, Farzan M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO) Statement on the first meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) emergency committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV); Geneva, Switzerland; WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang X, Wu C, Li X, Song Y, Yao X, Wu X, Duan Y, Zhang H, Wang Y, Qian Z, Cui J, Lu J. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. 2020;Natl Sci Rev:nwaa036. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lessler J, Reich NG, Brookmeyer R, Perl TM, Nelson KE, Cummings DA. Incubation periods of acute respiratory viral infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:291–300. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JE, Jung S, Kim A, Park JE. MERS transmission and risk factors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:574. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5484-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virlogeux V, Park M, Wu JT, Cowling BJ. Association between severity of MERS-CoV infection and incubation period. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:526–528. doi: 10.3201/eid2203.151437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Virlogeux V, Fang VJ, Wu JT, Ho LM, Peiris JS, Leung GM, Cowling BJ. Brief report: Incubation period duration and severity of clinical disease following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Epidemiology. 2015;26:666–669. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang X, Rayner S, Luo MH. Does SARS-CoV-2 has a longer incubation period than SARS and MERS? J Med Virol. 2020;92:476–478. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization (WHO) Report of the WHO-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Accessed 14 June 2020]. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pd.

- 19.Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145–151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song P, Li W, Xie J, Hou Y, You C. Cytokine storm induced by SARS-CoV-2. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;509:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyström K, Waldenström J, Tang KW, Lagging M. Ribavirin: pharmacology, multiple modes of action and possible future perspectives. Future Virol. 2019;14:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sung JJ, Wu A, Joynt GM, Yuen KY, Lee N, Chan PK, Cockram CS, Ahuja AT, Yu LM, Wong VW, Hui DS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: report of treatment and outcome after a major outbreak. Thorax. 2004;59:414–420. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.014076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peiris JS, Chu CM, Cheng VC, Chan KS, Hung IF, Poon LL, Law KI, Tang BS, Hon TY, Chan CS, Chan KH, Ng JS, Zheng BJ, Ng WL, Lai RW, Guan Y, Yuen KY HKU/UCH SARS Study Group. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan MH, Wong VW, Wong CK, Chan PK, Chu CM, Hui DS, Suen MW, Sung JJ, Chung SS, Lam CW. Serum LD1 isoenzyme and blood lymphocyte subsets as prognostic indicators for severe acute respiratory syndrome. J Intern Med. 2004;255:512–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsang K, Zhong NS. SARS: pharmacotherapy. Respirology. 2003;8(Suppl):S25–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Michael Posey L. Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsui PT, Kwok ML, Yuen H, Lai ST. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: clinical outcome and prognostic correlates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1064–1069. doi: 10.3201/eid0909.030362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, Yee WK, Wang T, Chan-Yeung M, Lam WK, Seto WH, Yam LY, Cheung TM, Wong PC, Lam B, Ip MS, Chan J, Yuen KY, Lai KN. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1977–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stern A, Skalsky K, Avni T, Carrara E, Leibovici L, Paul M. Corticosteroids for pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD007720. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007720.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Briel M, Spoorenberg SMC, Snijders D, Torres A, Fernandez-Serrano S, Meduri GU, Gabarrús A, Blum CA, Confalonieri M, Kasenda B, Siemieniuk RAC, Boersma W, Bos WJW, Christ-Crain M Ovidius Study Group; Capisce Study Group; STEP Study Group. Corticosteroids in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:346–354. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leong HN, Ang B, Earnest A, Teoh C, Xu W, Leo YS. Investigational use of ribavirin in the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome, Singapore, 2003. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:923–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vastag B. Old drugs for a new bug: influenza, HIV drugs enlisted to fight SARS. JAMA. 2003;290:1695–1696. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan KS, Lai ST, Chu CM, Tsui E, Tam CY, Wong MM, Tse MW, Que TL, Peiris JS, Sung J, Wong VC, Yuen KY. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with lopinavir/ritonavir: a multicentre retrospective matched cohort study. Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu CM, Cheng VC, Hung IF, Wong MM, Chan KH, Chan KS, Kao RY, Poon LL, Wong CL, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Yuen KY HKU/UCH SARS Study Group. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fritsch SD, Weichhart T. Effects of interferons and viruses on metabolism. Front Immunol. 2016;7:630. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin FC, Young HA. Interferons: success in anti-viral immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014;25:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loutfy MR, Blatt LM, Siminovitch KA, Ward S, Wolff B, Lho H, Pham DH, Deif H, LaMere EA, Chang M, Kain KC, Farcas GA, Ferguson P, Latchford M, Levy G, Dennis JW, Lai EK, Fish EN. Interferon alfacon-1 plus corticosteroids in severe acute respiratory syndrome: a preliminary study. JAMA. 2003;290:3222–3228. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.24.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng Y, Wong R, Soo YO, Wong WS, Lee CK, Ng MH, Chan P, Wong KC, Leung CB, Cheng G. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in SARS patients in Hong Kong. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:44–46. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soo YO, Cheng Y, Wong R, Hui DS, Lee CK, Tsang KK, Ng MH, Chan P, Cheng G, Sung JJ. Retrospective comparison of convalescent plasma with continuing high-dose methylprednisolone treatment in SARS patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:676–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen CY, Lee CH, Liu CY, Wang JH, Wang LM, Perng RP. Clinical features and outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome and predictive factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68:4–10. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho JC, Wu AY, Lam B, Ooi GC, Khong PL, Ho PL, Chan-Yeung M, Zhong NS, Ko C, Lam WK, Tsang KW. Pentaglobin in steroid-resistant severe acute respiratory syndrome. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:1173–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Momattin H, Mohammed K, Zumla A, Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA. Therapeutic options for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)--possible lessons from a systematic review of SARS-CoV therapy. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e792–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chong YP, Song JY, Seo YB, Choi JP, Shin HS, Rapid Response Team Antiviral treatment guidelines for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Infect Chemother. 2015;47:212–222. doi: 10.3947/ic.2015.47.3.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omrani AS, Saad MM, Baig K, Bahloul A, Abdul-Matin M, Alaidaroos AY, Almakhlafi GA, Albarrak MM, Memish ZA, Albarrak AM. Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a for severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1090–1095. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70920-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shalhoub S, Farahat F, Al-Jiffri A, Simhairi R, Shamma O, Siddiqi N, Mushtaq A. IFN-α2a or IFN-β1a in combination with ribavirin to treat Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus pneumonia: a retrospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2129–2132. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin Y, Yang H, Ji W, Wu W, Chen S, Zhang W, Duan G. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of COVID-19. Viruses. 2020;12:3722. doi: 10.3390/v12040372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arabi YM, Shalhoub S, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, Al-Omari A, Al Qasim E, Jose J, Alraddadi B, Almotairi A, Al Khatib K, Abdulmomen A, Qushmaq I, Sindi AA, Mady A, Solaiman O, Al-Raddadi R, Maghrabi K, Ragab A, Al Mekhlafi GA, Balkhy HH, Al Harthy A, Kharaba A, Gramish JA, Al-Aithan AM, Al-Dawood A, Merson L, Hayden FG, Fowler R. Ribavirin and interferon therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome: a multicenter observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;70:1837–1844. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCreary EK, Pogue JM. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Treatment: A Review of Early and Emerging Options. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa105. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hung IF, Lung KC, Tso EY, Liu R, Chung TW, Chu MY, Ng YY, Lo J, Chan J, Tam AR, Shum HP, Chan V, Wu AK, Sin KM, Leung WS, Law WL, Lung DC, Sin S, Yeung P, Yip CC, Zhang RR, Fung AY, Yan EY, Leung KH, Ip JD, Chu AW, Chan WM, Ng AC, Lee R, Fung K, Yeung A, Wu TC, Chan JW, Yan WW, Chan WM, Chan JF, Lie AK, Tsang OT, Cheng VC, Que TL, Lau CS, Chan KH, To KK, Yuen KY. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, Liu W, Wang J, Fan G, Ruan L, Song B, Cai Y, Wei M, Li X, Xia J, Chen N, Xiang J, Yu T, Bai T, Xie X, Zhang L, Li C, Yuan Y, Chen H, Li H, Huang H, Tu S, Gong F, Liu Y, Wei Y, Dong C, Zhou F, Gu X, Xu J, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Li H, Shang L, Wang K, Li K, Zhou X, Dong X, Qu Z, Lu S, Hu X, Ruan S, Luo S, Wu J, Peng L, Cheng F, Pan L, Zou J, Jia C, Wang J, Liu X, Wang S, Wu X, Ge Q, He J, Zhan H, Qiu F, Guo L, Huang C, Jaki T, Hayden FG, Horby PW, Zhang D, Wang C. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu L, Chen S, Fu Y, Gao Z, Long H, Wang JM, Ren HW, Zuo Y, Li H, Wang J, Xu QB, Yu WX, Liu J, Shao C, Hao JJ, Wang CZ, Ma Y, Wang Z, Yanagihara R, Deng Y. Risk factors associated with clinical outcomes in 323 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa539. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y, Xie Z, Lin W, Cai W, Wen C, Guan Y, Mo X, Wang J, Wang Y, Peng P, Chen X, Hong W, Xiao G, Liu J, Zhang L, Hu F, Li F, Li F, Zhang F, Deng X, Li L. An exploratory randomized controlled study on the efficacy and safety of lopinavir/ritonavir or arbidol treating adult patients hospitalized with mild/moderate COVID-19 (ELACOI) medRxiv. 2020 [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elfiky AA. Anti-HCV, nucleotide inhibitors, repurposing against COVID-19. Life Sci. 2020;248:117477. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, Ericson K, Wilkerson S, Tural A, Diaz G, Cohn A, Fox L, Patel A, Gerber SI, Kim L, Tong S, Lu X, Lindstrom S, Pallansch MA, Weldon WC, Biggs HM, Uyeki TM, Pillai SK Washington State 2019-nCoV Case Investigation Team. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.The COVID-19 investigation team. First 12 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0877-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, Fu S, Gao L, Cheng Z, Lu Q, Hu Y, Luo G, Wang K, Lu Y, Li H, Wang S, Ruan S, Yang C, Mei C, Wang Y, Ding D, Wu F, Tang X, Ye X, Ye Y, Liu B, Yang J, Yin W, Wang A, Fan G, Zhou F, Liu Z, Gu X, Xu J, Shang L, Zhang Y, Cao L, Guo T, Wan Y, Qin H, Jiang Y, Jaki T, Hayden FG, Horby PW, Cao B, Wang C. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Institutes of Health (NIH) NIH clinical trial shows remdesivir accelerates recovery from advanced COVID-19. [Accessed 1 May 2020]. Available at: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-clinical-trial-shows-remdesivir-accelerates-recovery-advanced-covid-19.

- 63.Lim J, Jeon S, Shin HY, Kim MJ, Seong YM, Lee WJ, Choe KW, Kang YM, Lee B, Park SJ. The author's response: Case of the index patient who caused tertiary transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea: the application of lopinavir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia Monitored by quantitative RT-PCR. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e79. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han W, Quan B, Guo Y, Zhang J, Lu Y, Feng G, Wu Q, Fang F, Cheng L, Jiao N, Li X, Chen Q. The course of clinical diagnosis and treatment of a case infected with coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol. 2020;92:461–463. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Young BE, Ong SWX, Kalimuddin S, Low JG, Tan SY, Loh J, Ng OT, Marimuthu K, Ang LW, Mak TM, Lau SK, Anderson DE, Chan KS, Tan TY, Ng TY, Cui L, Said Z, Kurupatham L, Chen MI, Chan M, Vasoo S, Wang LF, Tan BH, Lin RTP, Lee VJM, Leo YS, Lye DC Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research Team. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020;323:1488–1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baden LR, Rubin EJ. Covid-19 - The search for effective therapy. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1851–1852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2005477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cai Q, Huang D, Ou P, Yu H, Zhu Z, Xia Z, Su Y, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Li Z, He Q, Liu L, Fu Y, Chen J. COVID-19 in a designated infectious diseases hospital outside Hubei Province, China. Allergy. 2020;75:1742–1752. doi: 10.1111/all.14309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan D, Liu XY, Zhu YN, Huang L, Dan BT, Zhang GJ, Gao YH. Factors associated with prolonged viral shedding and impact of lopinavir/ritonavir treatment in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2000799. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00799-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 treatment guidelines: Lopinavir/ritonavir and other HIV protease inhibitors. [Accessed 14 June 2020]. Available at: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/antiviral-therapy/lopinavir-ritonavir-and-other-hiv-protease-inhibitors/

- 70.Wu J, Li W, Shi X, Chen Z, Jiang B, Liu J, Wang D, Liu C, Meng Y, Cui L, Yu J, Cao H, Li L. Early antiviral treatment contributes to alleviate the severity and improve the prognosis of patients with novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) J Intern Med. 2020;288:128–138. doi: 10.1111/joim.13063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu Z, Lu Z, Xu T, Chen C, Yang G, Zha T, Lu J, Xue Y. Arbidol monotherapy is superior to lopinavir/ritonavir in treating COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:e21–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deng L, Li C, Zeng Q, Liu X, Li X, Zhang H, Hong Z, Xia J. Arbidol combined with LPV/r versus LPV/r alone against corona virus disease 2019: A retrospective cohort study. J Infect. 2020;81:e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cai Q, Yang M, Liu D, Chen J, Shu D, Xia J, Liao X, Gu Y, Cai Q, Yang Y, Shen C, Li X, Peng L, Huang D, Zhang J, Zhang S, Wang F, Liu J, Chen L, Chen S, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Cao R, Zhong W, Liu Y, Liu L. Experimental treatment with favipiravir for COVID-19: an open-label control study. Engineering (Beijing) 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.007. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen C, Zhang Y, Huang J, Yin P, Cheng Z, Wu J, Chen S, Zhang Y, Chen B, Lu M, Luo Y, Ju L, Zhang J, Wang X. Favipiravir versus arbidol for COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. medRxiv. 2020 [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shang L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Du R, Cao B. On the use of corticosteroids for 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Lancet. 2020;395:683–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395:473–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, Oczkowski S, Levy MM, Derde L, Dzierba A, Du B, Aboodi M, Wunsch H, Cecconi M, Koh Y, Chertow DS, Maitland K, Alshamsi F, Belley-Cote E, Greco M, Laundy M, Morgan JS, Kesecioglu J, McGeer A, Mermel L, Mammen MJ, Alexander PE, Arrington A, Centofanti JE, Citerio G, Baw B, Memish ZA, Hammond N, Hayden FG, Evans L, Rhodes A. Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:854–887. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rygård SL, Butler E, Granholm A, Møller MH, Cohen J, Finfer S, Perner A, Myburgh J, Venkatesh B, Delaney A. Low-dose corticosteroids for adult patients with septic shock: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1003–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, Sindi AA, Almekhlafi GA, Hussein MA, Jose J, Pinto R, Al-Omari A, Kharaba A, Almotairi A, Al Khatib K, Alraddadi B, Shalhoub S, Abdulmomen A, Qushmaq I, Mady A, Solaiman O, Al-Aithan AM, Al-Raddadi R, Ragab A, Balkhy HH, Al Harthy A, Deeb AM, Al Mutairi H, Al-Dawood A, Merson L, Hayden FG, Fowler RA Saudi Critical Care Trial Group. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, Cui C, Huang B, Niu P, Liu X, Zhao L, Dong E, Song C, Zhan S, Lu R, Li H, Tan W, Liu D. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:732–739. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M, Giarratano A, Einav S. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J Crit Care. 2020;57:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Million M, Lagier JC, Gautret P, Colson P, Fournier PE, Amrane S, Hocquart M, Mailhe M, Esteves-Vieira V, Doudier B, Aubry C, Correard F, Giraud-Gatineau A, Roussel Y, Berenger C, Cassir N, Seng P, Zandotti C, Dhiver C, Ravaux I, Tomei C, Eldin C, Tissot-Dupont H, Honoré S, Stein A, Jacquier A, Deharo JC, Chabrière E, Levasseur A, Fenollar F, Rolain JM, Obadia Y, Brouqui P, Drancourt M, La Scola B, Parola P, Raoult D. Early treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: A retrospective analysis of 1061 cases in Marseille, France. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;35:101738. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rosenberg ES, Dufort EM, Udo T, Wilberschied LA, Kumar J, Tesoriero J, Weinberg P, Kirkwood J, Muse A, DeHovitz J, Blog DS, Hutton B, Holtgrave DR, Zucker HA. Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York State. JAMA. 2020;323:2493–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Geleris J, Sun Y, Platt J, Zucker J, Baldwin M, Hripcsak G, Labella A, Manson DK, Kubin C, Barr RG, Sobieszczyk ME, Schluger NW. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2411–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mahévas M, Tran VT, Roumier M, Chabrol A, Paule R, Guillaud C, Fois E, Lepeule R, Szwebel TA, Lescure FX, Schlemmer F, Matignon M, Khellaf M, Crickx E, Terrier B, Morbieu C, Legendre P, Dang J, Schoindre Y, Pawlotsky JM, Michel M, Perrodeau E, Carlier N, Roche N, de Lastours V, Ourghanlian C, Kerneis S, Ménager P, Mouthon L, Audureau E, Ravaud P, Godeau B, Gallien S, Costedoat-Chalumeau N. Clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with covid-19 pneumonia who require oxygen: observational comparative study using routine care data. BMJ. 2020;369:m1844. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Magagnoli J, Narendran S, Pereira F, Cummings T, Hardin JW, Sutton SS, Ambati J. Outcomes of hydroxychloroquine usage in United States veterans hospitalized with Covid-19. Med (N Y) 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2020.06.001. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu B, Li C, Chen P, Zhou N, Wang L, Li J, Jiang H, Wang DW. Low dose of hydroxychloroquine reduces fatality of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;15:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1732-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen J, Liu D, Liu L, Liu P, Xu Q, Xia L, Ling Y, Huang D, Song S, Zhang D, Qian Z, Li T, Shen Y, Lu H. A pilot study of hydroxychloroquine in treatment of patients with moderate COVID-19. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;49:215–219. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, Doudier B, Courjon J, Giordanengo V, Vieira VE, Tissot Dupont H, Honoré S, Colson P, Chabrière E, La Scola B, Rolain JM, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:105949. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sarma P, Kaur H, Kumar H, Mahendru D, Avti P, Bhattacharyya A, Prajapat M, Shekhar N, Kumar S, Singh R, Singh A, Dhibar DP, Prakash A, Medhi B. Virological and clinical cure in Covid-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:776–785. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen Z, Hu J, Zhang Z, Jiang S, Han S, Yan D, Zhuang R, Hu B, Zhang Z. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: results of a randomized clinical trial. medRxiv. 2020 [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bessière F, Roccia H, Delinière A, Charrière R, Chevalier P, Argaud L, Cour M. Assessment of QT intervals in a case series of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection treated with hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with azithromycin in an intensive care unit. JAMA Cardiol. 2020:e201787. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Funck-Brentano C, Salem JE. Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19: why might they be hazardous? Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31174-0. [Epu ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mair-Jenkins J, Saavedra-Campos M, Baillie JK, Cleary P, Khaw FM, Lim WS, Makki S, Rooney KD, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Beck CR Convalescent Plasma Study Group. The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:80–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, Yang Y, Li J, Yuan J, Wang F, Li D, Yang M, Xing L, Wei J, Xiao H, Yang Y, Qu J, Qing L, Chen L, Xu Z, Peng L, Li Y, Zheng H, Chen F, Huang K, Jiang Y, Liu D, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Liu L. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020;323:1582–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roback JD, Guarner J. Convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19: possibilities and challenges. JAMA. 2020;323:1561–1562. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ahn JY, Sohn Y, Lee SH, Cho Y, Hyun JH, Baek YJ, Jeong SJ, Kim JH, Ku NS, Yeom JS, Roh J, Ahn MY, Chin BS, Kim YS, Lee H, Yong D, Kim HO, Kim S, Choi JY. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in two COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e149. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu T, Zhang J, Yang Y, Ma H, Li Z, Zhang J, Cheng J, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Xia Z, Zhang L, Wu G, Yi J. The potential role of IL-6 in monitoring severe case of coronavirus disease 2019. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.15252/emmm.202012421. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xu X, Han M, Li T, Sun W, Wang D, Fu B, Zhou Y, Zheng X, Yang Y, Li X, Zhang X, Pan A, Wei H. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:10970–10975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jeong SJ, Han SH, Kim CO, Choi JY, Kim JM. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody attenuates inflammation and decreases mortality in an experimental model of severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2013;17:R97. doi: 10.1186/cc12742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]