Abstract

Bruxism, specifically sleep bruxism (SB), is a worldwide discussed topic in the literature; however, there is insufficient evidence to define and support a standard approach for the treatment of SB. The purpose of this overview was to map the evidence from systematic reviews (SR), examining the effects of interventions to improve chronic pain related to bruxism. The methodological quality of SRs was assessed using the AMSTAR-2 tool. We conducted a comprehensive literature search in April 2020, in the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, MEDLINE, LILACS, BBO, and Epistemonikos. Nine SRs with critically low to high methodological quality were included. Considering the main findings, botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) showed a significant pain and sleep bruxism frequency reduction when compared to placebo or conventional treatment (behavioral therapy, occlusal splints, and drugs), after 6 and 12 months. Occlusal splints combined to muscle massage showed some benefit in pain reduction. There was no difference in pain and bruxism frequency between biofeedback therapy and an inactive control group. Regarding drug therapy, there is no difference when amitriptyline, bromocriptine, clonidine, propranolol, and levodopa were compared to placebo. In conclusion, there is some evidence to support the use of occlusal splints plus massage, and BTX-A to reduce chronic pain related to SB. No evidence was provided to support the recommendation of biofeedback therapy and drug therapy. There is still a need for more methodologically rigorous randomized clinical trials (RCT) to be conducted on the efficacy and safety of different therapies for SB.

Keywords: sleep bruxism, pain management, evidence-based dentistry

Introduction

Bruxism can be classified as sleep bruxism (SB), which is defined as a masticatory muscle activity during sleep, characterized as rhythmic (phasic) or non-rhythmic (tonic) movements. This activity is not observed in healthy individuals.1

Pain in the mandible muscles, sensibility in the masseter and temporal muscle regions, morning headaches, and fatigue are commonly reported in individuals with SB. However, the relationship between SB and chronic pain reporting is difficult to evaluate. The main limitation of this association is that the nature of pain is not specified and, therefore, a multitude of complaints can be included. The interaction between bruxism and chronic pain cannot be extrapolated to causality or consequence. Central pathophysiological mechanisms are considered to play an important role in SB. Additionally, psychological factors, such as stress and anxiety, seem to exacerbate the symptoms of SB.2,3

The standard reference for SB diagnosis is polysomnography (PSG) with audio-video recordings. Other methods that measure the activity of masticatory muscles during sleep are PSG without audio-video recordings or electromyography (EMG) recorded with portable devices.4 SB criteria include one or more signs: tooth-grinding sounds during sleep, tooth wear, jaw-muscle pain or fatigue. Furthermore, pain intensity can be assessed by a visual analog scale (VAS).5

There are several treatment approaches for this disease, but the common target being muscle relaxation. Studies suggest that the treatment can be conducted with oral appliance, which seems to be effective in reducing SB activity, with a better resolution with devices that provide a large extension of the mandibular advancement. The most usual pharmacological approaches are botulinum toxin, clonazepam, and clonidine, which can improve SB symptoms when compared to placebo. The potential benefit of biofeedback and cognitive-behavioral approaches to SB management is not fully supported.6 Electrical stimulation in the masseter muscle seems to be effective in reducing pain. However, there is insufficient evidence to define and support a standard approach for the treatment of SB.

Therefore, it is necessary to identify and map the higher level of evidence in the literature in order to define the best strategies to manage bruxism in the clinical setting. Numerous SRs on treatment for bruxism have been conducted in the last years, but a comprehensive evidence synthesis and critical appraisal is yet missing. Thus, the purpose of this study was to map the evidence from SRs examining the effects of interventions to improve chronic pain in individuals with bruxism.

Methods

This overview of systematic reviews (SR) was conducted following the guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 7 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of systematic reviews PRISMA statement throughout this manuscript.8

Criteria for Considering Reviews for Inclusion

Types of Reviews

All SRs (with or without meta-analysis) of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were included. To minimize the risk of bias, SRs involving non-randomized controlled study (NRS) designs were included only if the data from RCTs were presented (or available) separately.

Types of Participants

SRs that evaluated any type of treatment to improve pain in adults with bruxism (sleep or awake) were considered eligible. SRs that included studies involving children were included only if data were presented separately. SRs that assessed both bruxism and temporomandibular disorders (TMD) or those including patients with any developmental dysfunctions were excluded.

Types of Interventions

Any type of intervention used on the management of bruxism, compared to placebo, no treatment or another active intervention.

Types of Outcomes

Primary outcomes were any validated measures of pain (such as a visual analogue scale – VAS) and any adverse events arising from interventions. Secondary outcomes included patient-reported clinical symptoms (such as teeth grinding and jaw stiffness), patient preference, number of bruxism episodes, sleep disturbance indexes, and quality of life. Any time point reported in SRs was considered.

Searching for Systematic Reviews

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in April 2020 with no restriction regarding date, language or status of the publication. Sensitive search strategies (Supplementary File 1) were developed for the following databases:

• Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials – CENTRAL (via Wiley);

• EMBASE (via Elsevier);

• MEDLINE (via PubMed);

• Literatura Latino Americana em Ciências da Saúde e do Caribe – LILACS (via Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde - BVS), Bibliografia Brasileira de Odontologia – BBO (via BVS);

• Epistemonikos (systematic review repository)

We also screened the reference lists of all included SRs, and other relevant publications, to identify additional, potentially relevant, studies.

Selecting Systematic Reviews for Inclusion

All titles and abstracts retrieved from the search were assessed for eligibility by two review authors independently (ALCM and ACRTH), using the software Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org/).9 Potentially relevant SRs were selected for full-text reading, and those that fulfilled the predetermined inclusion criteria were included in this overview. Discrepancies were solved by a third author (SKB).

Data Extraction

Two authors (ALCM and ACRTH) independently extracted data from included SRs and a third author (LM) solved any discrepancies. Data were extracted from SRs using a standardized data extraction form including details on participants’ characteristics (total number of participants, age, diagnosis criteria), number and design of primary studies included, intervention(s), comparator(s), outcomes assessed, assessment of methodological quality/risk of bias of primary studies, quantitative outcome data (meta-analysis or a summary of individual studies results) and the assessment of the certainty of evidence (GRADE approach – Grading of Recommendations, Assessments, Developments and Evaluations). Missing or inadequately reported data from SRs were collected directly from the underlying primary studies.10,11

Data Synthesis

Data from meta-analyses, or individual RCTs, were summarized narratively as described by SRs. The trials included in each review were mapped to identify the presence of overlap i.e. primary studies included in more than one eligible SR. The number of overlapping trials was summarized and the results from these studies were presented individually to avoid double counting of outcome data.7,12 Missing numerical data were collected from underlying RCTs and, when possible (data available), the estimated treatment effects were calculated (mean difference for continuous outcome and risk ratio for dichotomous outcome, with 95% confidence interval), by using the Revman 5.4 software.13

Assessing Methodological Quality of Included Systematic Reviews

Two authors (ALCM and SBK) independently assessed the methodological quality and risk of bias of SRs using the AMSTAR-2 tool (Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews).14 AMSTAR-2 provides guidance to rate the overall confidence in the results of a review in critically low (more than one critical failure); low (a critical failure); moderate (more than one non-critical failure) and high (none or non-critical failure). The certainty of the body of evidence was generated through the checklist available on the AMSTAR-2 website (http://amstar.ca/Amstar_Checklist.php).

Results

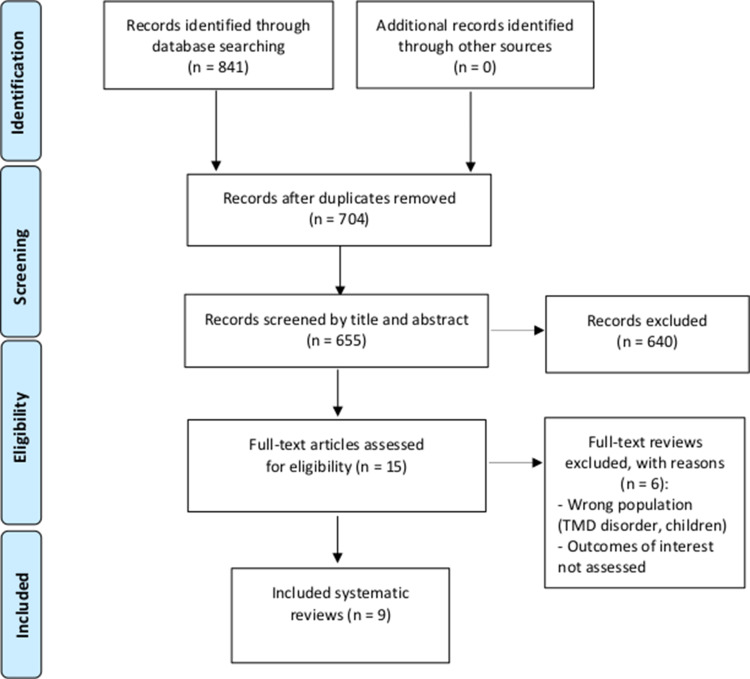

Initial search results retrieved 841 records. After removed 186 duplicates, 655 studies by title and abstracts were screened, of which 15 were considered eligible and the full texts were analyzed. Six SRs were excluded, and the reasons are detailed in the flow diagram. Thus, nine15–23 SRs were included for analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process. (Adapted of an study (8)).

Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews

The main characteristics of the included SRs are presented in Table 1. SRs were published between 2005 and 2019. Four SRs included only RCTs16,18,20,23 as primary study and five included NRSs (before-after studies).15,17,19,21 The number of included primary studies ranged from 2 to 16. Total samples ranged between 32 and 240 participants, and the mean age ranged from 18 to 54 years. The interventions analyzed were botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A), occlusal appliances, biofeedback therapy, and drug therapy.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews

| Author/ Year/ |

Type of Included Studies | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Assessment of Methodological Quality/Risk of Bias | Meta-Analysis | Certainty of Evidence Assessment (GRADE) | AMSTAR −2 Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dela Torre Canales et al, 201715 | 3 RCTs 2 before-after studies |

SB 18 to 45 years (n = 188) |

BTX-A Masseter and/or temporalis muscle, bilaterally. Dose: 20 to 80 IU |

Placebo, Different sites of injection (masseter alone or masseter and temporalis) | Cochrane RoB tool CASP checklist |

No | No | Low quality |

| Fernández-Núñez et al, 201916 | 4 RCTs | SB 20 to 45 years (n = 112) |

BTX-A Masseter and/or temporalis muscle, bilaterally. Dose: 20 to 80 IU |

Placebo, Conventional treatment (behavioral therapy, occlusal splint and drugs) |

Cochrane RoB tool | No | No | Low quality |

| Long et al, 201217 | 2 RCTs 2 before-after studies |

SB 20 to 45 years (n = 57) |

BTX-A Masseter and/or temporalis muscle, bilaterally. Dose: 20 to 80 IU |

Placebo | Cochrane RoB tool | No | No | Low quality |

| Sposito et al, 201418 | 2 RCTs | SB 20 to 45 years (n = 32) |

BTX-A Masseter and/or temporalis muscle, bilaterally. Dose: 20 to 80 IU |

Placebo | Jadad scale | No | No | Critically Low quality |

| Jokubaukas et al, 201719 | 9 RCTs 7 before-after studies |

SB 25.6 to 34.7 years (n = 398) |

Occlusal splints (treatment period ranging from ranging from 1 night to 3 months) |

MAD, Different design appliances biofeedback, Behavioural therapy, Massage |

Cochrane RoB tool CASP checklist |

No | No | Low quality |

| Macedo et al, 200520 | 5 RCTs | SB mean 24 to 34.8 years (n = 54) |

Occlusal splints (daily, 2 to 4 weeks of treatment) |

Palatal splint, MAD and TENS | Cochrane RoB tool | Yes | No | High quality |

| Jokubaukas et al, 201821 | 4 RCTs 2 before-after studies |

SB mean 24 to 34.8 years (n = 86) |

Biofeedback therapy (auditory, electrical, and visual stimulus) 1 to 5 nights of treatment |

Inactive, No treatment, Splint, Occlusal adjustment | Cochrane RoB tool | Yes | Yes | Moderate quality |

| Wang et al, 201322 | 6 RCTs 1 before-after study |

SB mean 24 to 34.8 years (n = 240) |

Biofeedback therapy (auditory, electrical and visual stimulus) 1 to 5 nights of treatment |

Inactive, No treatment, Splint, Occlusal adjustment | Cochrane RoB tool | Yes | No | Moderate quality |

| Macedo et al, 201423 | 7 RCTs (crossover) | SB mean 19 to 54 years (n = 80) |

Drug therapy (treatment period: two days to four weeks) |

Placebo, No treatment, Other drugs | Cochrane RoB tool | Yes | No | High quality |

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized clinical trial; SB, sleep bruxism; BTX-A, botulinum toxin type A; VAS, visual analogue scale; CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme before–after study checklist; MD, mean difference; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; TENS, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation; MAD, mandibular advancement device; NR, not reported.

All included SRs presented a small sample size and included patients diagnosed with sleep bruxism. None of them was about awake bruxism.

Five SRs15–19 did not conduct meta-analyses due to the clinical and methodological heterogeneity between included studies. None of the included SRs conducted a subgroup analysis. Sensitivity analysis was performed by two SRs, to analyze possible changes in the meta-analysis results with fixed and random effect models.

The methodological quality of SRs assessed by the AMSTAR-2 tool and was classified as critically low to high (Supplementary File 2). Only four SRs19–21,23 presented the previous registration protocol of systematic review. Most of the included SRs conducted a limited search, with language and date restrictions, and did not search in trial register databases, gray literature, and in the reference lists of included studies.

Five overlap studies were identified, in a total of 36 RCTs included in the SRs (13.8%), two of them on botulinum toxin type A (2 in 5), and three on biofeedback therapy (3 in 10). To avoid duplicated results, we collected and presented the main results from individual studies of each SR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overlapping Primary Studies and Main Results for Each Intervention

| Intervention | Number of SRs | Number of Included RCTs | Number of Overlapping RCTs | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BTX-A | 4 | 5 | 2 |

Compared to placebo, BTX-A presented:

drugs), BTX-A presented:

|

| Occlusal splint | 2 | 14 | 0 |

Compared with palatal splint, occlusal splint presented:

|

| Biofeedback therapy | 2 | 10 | 3 |

Compared to an inactive control, CES presented:

Certainty of evidence: low to moderate |

| Drug therapy | 1 | 7 | 0 |

Compared with placebo, the following drugs showed: Amitriptyline:

|

Abbreviations: BTX-A, botulinum toxin type A; SR, systematic review; MD, mean difference; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; RR, relative risk; TENS, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation; TMJ, temporomandibular joint; MAD, mandibular advancement device; CES, contingent electrical stimulation.

Discussion

Bruxism, specifically sleep bruxism (SB), is a worldwide discussed topic in the literature, and, its forms of treatment.24 Therefore, updates and critical appraisal of existing high-quality evidence are necessary to adequately inform healthcare practitioners. It is interesting to note that even with a large number of published studies, the methodological quality is still low, making the strength of recommendation for SB treatments weak. In this overview, we selected the most used strategies to manage bruxism in the clinical setting based on the results from systematic reviews (SR).

The methodological assessment with the AMSTAR-2 tool showed a variety quality of the included SRs, ranging from critically low to high. Only two reviews were classified as high quality due to the methodological rigor proposed by Cochrane. The risk of bias of primary included studies was predominantly unclear to low risk of bias, presenting methodological flaws mainly regarding the lack of randomization and allocation concealment description, as well as blinding of participants and outcome assessors. None of the systematic reviews assessed the certainty of the body of evidence with the GRADE approach, which limits the confidence in the clinical recommendations based on these findings.

Taking the results of all included SRs together, the main findings showed that botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) seems to improve pain relief at chewing and sleep bruxism episodes when compared to placebo, after 3 to 6 months of follow up. When compared to conventional treatments (behavioral therapy, occlusal splints, drugs), BTX-A presented significant pain reduction, after 6 and 12 months. Considering different BTX-A injections on masseter alone versus masseter and temporalis, no difference in morning jaw stiffness and subjective bruxism events was described after 1 month.15–18

When occlusal splint was compared with palatal splint, there are no differences in arousal index, after 2 to 4 weeks of treatment, and, in the number of bruxism episodes per hour sleep. However, a higher proportion of participants reported preference by occlusal splints when compared to mandibular advancement devices. A qualitative review showed the effectiveness of occlusal splint in bruxism signs and symptoms was consistent; however, although with longer follow‐up time.6 Additionally, occlusal splint combined with muscle massage improves the intensity of bruxism signs and symptoms when compared to massage alone.19,20

Botulinum toxin reduces the intensity of muscle contraction15–18 for a period of 4–6 months so it has a palliative effect. After this period, it loses its effect and the muscle returns to normal activity. It is important to note that this treatment does not solve the cause of bruxism.15–18 It is necessary to take these factors into account before indicating this therapeutic option for the patient. It is important to note those effects of continuous reapplication on effects or changes in the muscle structure and function. Is there any damage? It needs further evaluation. Is there an impairment in muscle function in the long run? There are doubts that clinical studies should evaluate in the future in order to better subsidize the indication of this palliative therapeutic resource with lots of limitations.

When biofeedback therapy was compared to inactive control, there was no difference in number of painful muscles, self-reported pain, muscle tension, maximum pain-free jaw opening and also no difference in bruxism frequency during sleep after 6-week treatment.20,21

The literature reports that despite clinical trials and case reports showing positive results for biofeedback, scientific evidence is still insufficient.22

The results of this overview seem to indicate that pharmacological treatments are not an interesting therapeutic option. It must be remembered that in the long term it can cause dependence and in addition are associated with adverse side effects. Regarding drug therapy, there was no difference when amitriptyline, bromocriptine, clonidine, propranolol, or levodopa were compared to placebo.21,22

For the treatment of bruxism, the first choice should be based on safe and conservative treatments.

Occlusal plaque seems to be an acceptable and safe treatment alternative in the short and medium term, however it is not a definitive treatment for this pathology.20 It is necessary to carry out more randomized clinical studies, with a long follow-up time and with representative samples, in order to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the treatments proposed for the control and management of bruxism.20

On the other hand, there was no significant report of adverse events resulting from the interventions. This fact seems to demonstrate the probable safety of the treatments for SB. However, long-term follow-ups have not been assessed by primary studies and, therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution.

Our overview drew similar conclusions to other recent umbrella reviews regarding the effects of different intervention options for pain reduction in SB.6,24,25 The benefits of occlusal devices have also been reported, as well as the absence of evidence to recommend any other treatment such as BTX-A, medication, biofeedback and psychological interventions.

This overview carried out a comprehensive search in different databases and analyzed nine SRs, involving a total of 56 primary clinical studies. We identified five overlapping studies, mainly on BTX-A reviews. The results of these primary studies were summarized and presented once, to avoid unnecessary duplication of information. However, it is important to emphasize that SRs should be conducted when there is a need to update an issue or in the case of a new or different clinical question.12

Conclusion

Based on systematic reviews with critically low to high methodological quality, there is some evidence to support the use of occlusal splints combined to muscle massage and botulinum toxin type A to reduce chronic pain related to sleep bruxism. No evidence was provided to support the recommendation of biofeedback therapy and drug therapy. There is still a need for more methodologically rigorous RCTs to be conducted on the efficacy and safety of different therapies for SB.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lobbezoo F, Ahlberg J, Raphael KG, et al. International consensus on the assessment of bruxism: report of a work in progress. J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45(11):837–844. doi: 10.1111/joor.12663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoury S, Carra MC, Huynh N, Montplaisir J, Lavigne GL. Sleep bruxism-tooth grinding prevalence, characteristics, and familial aggregation: a large cross-sectional survey and polysomnographic validation. Sleep. 2016;39(11):2049–2056. doi: 10.5665/sleep.6242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen ML, Araujo P, Frange C, Tufik S. Sleep disturbance and pain: a tale of two common problems. Chest. 2018;154(5):1249–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guarda-Nardini L, Manfredini D, Salamone M, Salmaso L, Tonello S, Ferronato G. Efficacy of botulinum toxin in treating myofascial pain in bruxers: a controlled placebo pilot study. Cranio. 2008;26(2):126–135. doi: 10.1179/crn.2008.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jadhao VA, Lokhande N, Habbu SG, Sewane S, Dongare S, Goyal N. Efficacy of botulinum toxin in treating myofascial pain and occlusal force characteristics of masticatory muscles in bruxism. Indian J Dent Res. 2017;28(5):493–497. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_125_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manfredini D, Ahlberg J, Winocur E, Lobbezoo F. Management of sleep bruxism in adults: a qualitative systematic literature review. J Oral Rehabil. 2015;42(11):862–874. doi: 10.1111/joor.12322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: overviews of reviews In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0 (Updated March 2020). Cochrane; 2020. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed August22, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj. 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollock M, Fernandes R, Becker L, Featherstone R, Hartling L. What guidance is available for researchers conducting overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions? A scoping review and qualitative metasummary. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0367-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballard M, Montgomery P. Risk of bias in overviews of reviews: a scoping review of methodological guidance and four-item checklist. Res Synth Methods. 2017;8(1):92–108. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pieper D, Antoine S, Mathes T, Neugebauer E, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (Revman) [Computer Program]. Version 5.2.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DelaTorre CG, Câmara-Souza MB, Do Amaral CF, Garcia R, Manfredini D. Is there enough evidence to use botulinum toxin injections for bruxism management? A systematic literature review. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-Núñez T, Amghar-Maach S, Gay-Escoda C. Efficacy of botulinum toxin in the treatment of bruxism: systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24(4):e416–e424. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long H, Liao Z, Wang Y, Liao L, Lai W. Efficacy of botulinum toxins on bruxism: an evidence-based review. Int Dent J. 2012;62:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00085.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sposito MMM, Teixeira SAFT. Botulinum Toxin A for bruxism: a systematic review. Acta Fisiatr. 2014;21(4):201–204. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jokubauskas L, Baltrušaitytė A, Pileičikienė G. Oral appliances for managing sleep bruxism in adults: a systematic review from 2007 to 2017. J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45(1):81–95. doi: 10.1111/joor.12558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva CR, Saconato MA, Prado GF, Türp JC, Türp JC. Occlusal splints for treating sleep bruxism (tooth grinding). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005514.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jokubauskas L, Baltrušaitytė A. Efficacy of biofeedback therapy on sleep bruxism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45:485–495. doi: 10.1111/joor.12628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L-F, Long H, Deng M, et al. Biofeedback treatment for sleep bruxism: a systematic review. Sleep Breath. 2014;18:235–242. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0871-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macedo CR, Macedo EC, Torloni MR, Silva AB, Prado GF. Pharmacotherapy for sleep bruxism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005578.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beddis H, Pemberton M, Davies S. Sleep bruxism: an overview for clinicians. Br Dent J. 2018;225(6):497–501. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melo G, Duarte J, Pauletto P, et al. Bruxism: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(7):666–690. doi: 10.1111/joor.12801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]