Abstract

Background

Vitamin D supplementation lowers exacerbation frequency in severe vitamin D-deficient patients with COPD. Data regarding the effect of vitamin D on elastin degradation are lacking. Based on the vitamin's anti-inflammatory properties, we hypothesised that vitamin D supplementation reduces elastin degradation, particularly in vitamin D-deficient COPD patients. We assessed the effect of vitamin D status and supplementation on elastin degradation by measuring plasma desmosine, a biomarker of elastin degradation.

Methods

Desmosine was measured every 4 months in plasma of 142 vitamin D-naïve COPD patients from the Leuven vitamin D intervention trial (100 000 IU vitamin D3 supplementation every 4 weeks for 1 year).

Results

No significant association was found between baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and desmosine levels. No significant difference in desmosine change over time was found between the placebo and intervention group during the course of the trial. In the intervention arm, an unexpected inverse association was found between desmosine change and baseline 25(OH)D levels (p=0.005).

Conclusions

Vitamin D supplementation did not have a significant overall effect on elastin degradation compared to placebo. Contrary to our hypothesis, the intervention decelerated elastin degradation in vitamin D-sufficient COPD patients and not in vitamin D-deficient subjects.

Short abstract

Vitamin D supplementation does not have a significant overall effect on elastin degradation. Vitamin D decelerates elastin degradation in vitamin D-sufficient, but not in vitamin D-deficient, COPD patients. https://bit.ly/2A9H9P7

Introduction

The pathogenesis of COPD is characterised by chronic inflammation and an imbalance in elastase/anti-elastase activity leading to accelerated elastin degradation and emphysema. Although tobacco smoke exposure has been clearly linked to the risk of COPD, not all smokers will develop irreversible airway obstruction. Factors other than smoking – such as genetic and environmental factors – must therefore be implicated. Different studies have suggested a role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis of COPD [1–3].

Vitamin D is either exogenously obtained from food or endogenously produced in the skin through sun (UV-B) exposure [4]. In the liver, vitamin D is hydroxylated into 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), which is used for serum measurements because of its long half-life of 2–3 weeks [4]. To become biologically active, 25(OH)D requires an additional hydroxylation step in the kidneys by 1-α-hydroxylase, an enzyme that is also present in different inflammatory and epithelial cells [4]. The latter autocrine and paracrine activation has been linked to a variety of non-calcemic effects of vitamin D, which include anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative properties. The vast pool of epidemiological data linking vitamin D deficiency – defined as a serum 25(OH)D level below 20 ng.mL−1 (=50 nmol.L−1) – to many infectious and chronic inflammatory diseases including COPD is in line with these mechanistic functions [4]. Vitamin D deficiency is a proven risk factor for COPD and is associated with increasing disease severity [5]. A recent meta-analysis also demonstrated that vitamin D supplementation substantially reduces exacerbation frequency in severe vitamin D-deficient (i.e. <10 ng.mL−1) COPD patients [6]. Furthermore, murine data demonstrated that low vitamin D status enhances the onset of COPD-like characteristics already after 6 weeks of cigarette smoke exposure [3]. Furthermore, vitamin D deficiency accelerates and aggravates the development of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema, which is potentially related to enhanced elastin breakdown [3].

Elastin is a unique protein providing elasticity, resilience and deformability to dynamic tissues, such as lungs and vasculature [7]. Elastin is an absolute requirement for both ventilation and circulation [7]. Elastogenesis starts with the synthesis of tropoelastin, which is subsequently secreted in the extracellular matrix and aligned with other monomers to form fibres [7]. These tropoelastin-polymers have to be cross-linked with each other by the enzyme lysyl oxidase in order to obtain elasticity and longevity [7]. During this cross-linking process, two amino acids, desmosine and isodesmosine (DES), are formed that are unique to cross-linked elastin [8]. Degradation of cross-linked elastin fibres in lungs and blood vessels by elastases can be quantified by measuring blood levels of DES [8]. Research has shown that plasma (p)DES levels are elevated in patients with COPD compared to age- and smoking-matched controls [8]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that pDES is a predictor of mortality in patients with COPD [8]. We therefore regard elastin degradation as an attractive biomarker for COPD and, potentially, as a novel therapeutic target.

Since vitamin D has anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, antiprotease and antimicrobial properties [9], we hypothesised that vitamin D supplementation in COPD patients might reduce the rate of elastin degradation, particularly in vitamin D-deficient subjects. In order to test this hypothesis, we measured pDES in patients with COPD from the Leuven vitamin D-randomised controlled trial before, during and at the end of the intervention period.

Methods

Subjects

The parent study was a single-centre (University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium), double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial, in which 182 COPD patients received either high-dose vitamin D (100 000 IU of vitamin D3) supplementation or placebo every 4 weeks for 1 year [1]. The study was approved by the local ethics review committee of the University Hospitals Leuven (S50722; EudraCT number: 2007-004755-11) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00666367). The 142 vitamin D-naïve participants from the Leuven vitamin D intervention trial were included in our ancillary study (table 1). Forty participants were excluded from our current study, as they were already using vitamin D supplementation at study entry. Details of the Leuven vitamin D intervention trial have been previously published [1].

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Vitamin D group | Placebo group | p-value |

|

Subjects n Men |

71 59 (83) |

71 62 (87) |

0.482 |

| Age years | 68±9 | 68±8 | 0.649 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current smokers | 13 (18) | 16 (23) | 0.288 |

| FEV1 L | 1.25±0.45 | 1.22±0.44 | 0.635 |

| FEV1 % pred | 45±16 | 43±14 | 0.508 |

| FVC L | 2.82±0.80 | 2.95±0.88 | 0.377 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.44±0.12 | 0.42±0.11 | 0.239 |

| DLCO % pred | 48±17 | 50±16 | 0.538 |

| GOLD stage | |||

| I | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.319 |

| II | 21 (30) | 19 (27) | 0.715 |

| III | 32 (45) | 38 (54) | 0.317 |

| IV | 17 (24) | 14 (20) | 0.546 |

Baseline characteristics of vitamin D and placebo groups at randomisation. Both groups were matched for all given variables. Data are presented as n (%) or mean±sd, unless otherwise stated. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Plasma desmosine measurements

The rate of elastin degradation was quantified by measuring pDES levels. Subjects with highest pDES concentrations were assumed to have the highest rates of elastin degradation. Isodesmosine and desmosine fractions were measured separately by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry as previously described using deuterium-labelled desmosine as an internal standard [10, 11]. Coefficient of variations of intra- and inter-assay imprecision were <10%; lower limit of quantification 0.2 ng.mL−1 and assay linearity up to 20 ng.mL−1. pDES levels were presented as the sum of isodesmosine and desmosine fractions. After randomisation, follow-up visits occurred every 4 months (at 4, 8 and 12 months). Blood was drawn independently from vitamin D intake. Blood samples were available from 142 patients at baseline, from 133 patients at 4 months, from 129 patients at 8 months and from 116 patients at 12 months. The plasma samples had been frozen at −80°C for 6 to 7 years. It is unlikely that the storage time influenced pDES concentrations given the extreme stability of DES.

Other serum measurements

Serum 25(OH)D levels were measured at baseline and after 12 months. Total serum 25(OH)D levels were measured in multiple batches by radioimmunoassay (DiaSorin, Brussels, Belgium) according to the standard protocol. These are mean values of duplicate measures. Levels were expressed in ng.mL−1 (conversion factor for nmol.L−1: 2.5).

Furthermore, serum calcium and phosphate levels were measured every 4 months to monitor safety of vitamin D supplementation.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were undertaken using SPSS Software (version 24, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Univariate linear regression analysis was used to assess associations between variables corrected for age as covariate. Repeated measurements linear mixed model analysis was used to determine pDES change during the course of the study measured at baseline, 4, 8 and 12 months, also corrected for age. A p<0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Baseline vitamin D status and desmosine

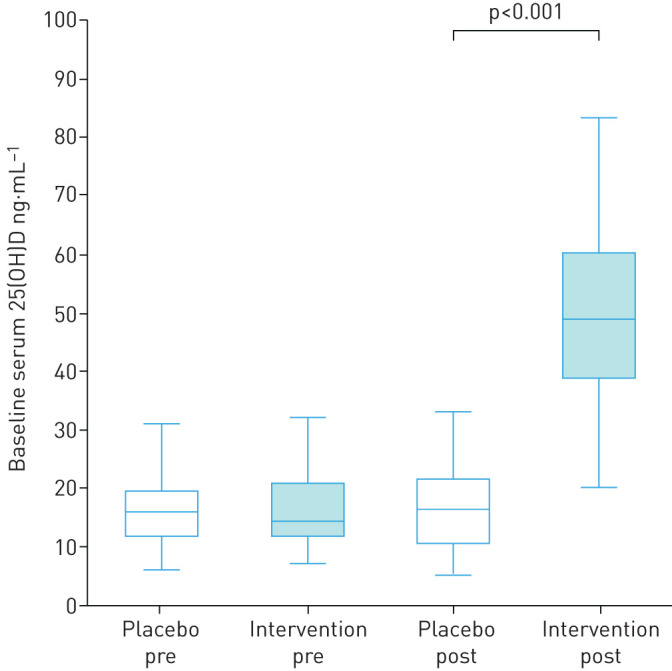

No significant difference in 25(OH)D levels was found between placebo and intervention groups at baseline. As expected, 25(OH)D levels were significantly higher in the intervention arm compared to the placebo arm at 12 months (p<0.001; figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

25(OH)D levels in placebo and intervention groups at baseline and 12 months. Boxplots (5th percentile, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile and 95th percentile) showing serum 25(OH) levels (ng.mL−1) at baseline (pre; n=71 in both groups) and 12 months (post; n=61 in placebo arm and n=56 in intervention arm). No significant difference in serum 25(OH)D levels was found between the placebo and intervention arm at baseline. 25(OH)D levels were significantly higher in the intervention arm compared to the placebo arm at 12 months (p<0.001).

A significant positive association was found between age and pDES levels (p<0.0005), and all pDES levels were therefore corrected for this variable.

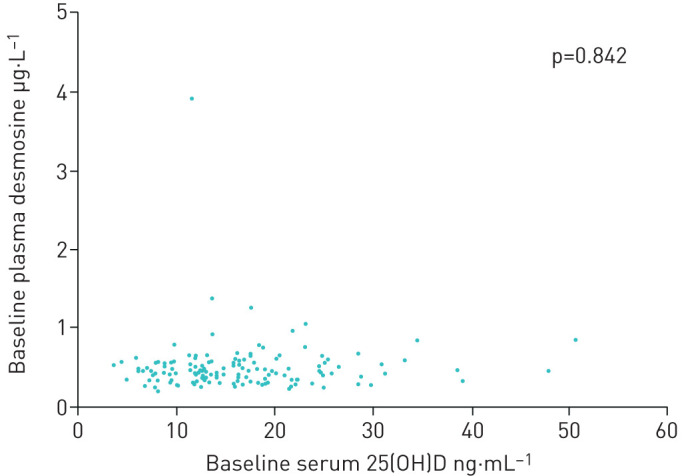

At baseline, no association was demonstrated between serum 25(OH)D and pDES levels (p=0.842; figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Association between 25(OH)D levels and desmosine at baseline. Scatter plot showing the relationship between baseline serum 25(OH) levels (ng.mL−1) and plasma desmosine levels (µg.L−1). No significant relationship was found (p=0.842). All 142 patients from both the placebo and intervention group were included at baseline.

Desmosine change during the study

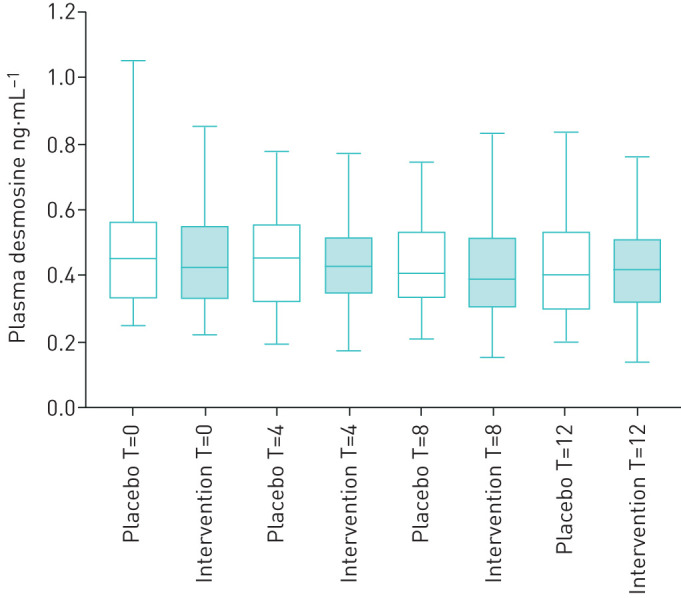

No significant difference in pDES levels was found between the placebo and intervention arm at any of the four time points (0, 4, 8 and 12 months; figure 3). No significant effect of vitamin D supplementation on pDES change was found during the course of the study compared to placebo using linear mixed model analysis (p=0.853).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of vitamin D and placebo on desmosine levels. Boxplots (5th percentile, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile and 95th percentile) showing plasma desmosine levels (µg.L−1) in placebo and intervention arms at four time points: baseline (T=0), 4 months (T=4), 8 months (T=8) and 12 months (T=12). No significant difference in plasma desmosine levels was found between the placebo and intervention arm at any of the four time points.

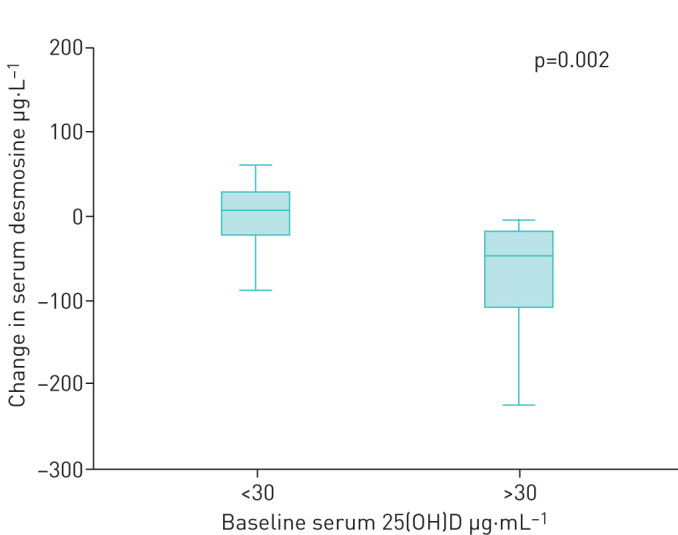

In the supplementation arm, a significant inverse interaction was found between baseline serum 25(OH)D levels and pDES change during the course of the study using linear mixed model analysis (p=0.005). In other words, whereas pDES levels slightly increased during the course of the study in vitamin D-supplemented subjects with lower baseline 25(OH)D levels, pDES levels significantly decreased in those with higher baseline 25(OH)D levels.

In the placebo arm, no significant effect of baseline serum 25(OH)D levels on pDES change during the course of the study was found using linear mixed model analysis (p=0.720). In the supplementation arm there was a significant decrease in plasma desmosine when comparing the group with serum 25(OH)D >30 ng·mL−1 to the group with a baseline 25(OH)D <30 ng·mL−1, 0.007 ng·L−1 versus −0.802 ng·L−1 (p=0.002) (figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of baseline 25(OH)D levels on desmosine change after vitamin D supplementation. Boxplots (5th percentile, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile and 95th percentile) showing the change in plasma desmosine levels (µg.L−1) over the course of the study and serum 25(OH)D levels (ng.mL−1) at baseline. A significant inverse correlation was found between the groups (p=0.002).

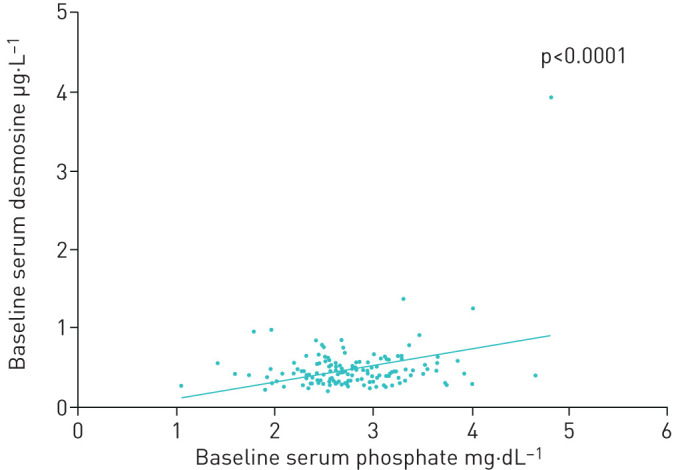

Baseline calcium, phosphate and desmosine

Vitamin D supplementation did not significantly influence serum calcium and phosphate levels. No significant association between baseline serum calcium and pDES levels was found in the total study group (p=0.230). A significant association between baseline serum phosphate and pDES levels was found, independent from the intervention (p<0.0001; figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Association between phosphate and desmosine levels at baseline. Scatterplot showing the association between baseline serum phosphate (mg.dL−1) and plasma desmosine levels (µg.L−1). All 142 patients from both the placebo and intervention group were included. A significant positive association was found between both variables (p<0.0001). Plasma desmosine = −0.739 + (age)*0.008 − (baseline serum phosphate)*0.233 (η2=0.157 and adjusted η2=0.145).

Discussion

We investigated the effects of serum 25(OH)D levels and high-dose vitamin D supplementation on the rate of elastin degradation in patients with COPD. Baseline serum 25(OH)D levels did not associate with elastin degradation markers. Vitamin D supplementation did not reduce elastin degradation in the whole study population compared to placebo, although a significant and unexpected association was found in the intervention arm between higher baseline serum 25(OH)D levels and a deceleration of elastin degradation during the course of the study.

Vitamin D has anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects [9], which could potentially dampen the rate of elastin degradation. Systemic inflammation in COPD is associated with higher circulating DES levels [8]. Furthermore, reactive oxygen species have the potential to oxidise and consequently weaken DES cross-links leading to accelerated elastin degradation [12]. We therefore speculated that vitamin D supplementation could favourably shift the elastase/anti-elastase balance and protect against elastin degradation. However, we did not observe a deceleration of elastin degradation in the total intervention arm. In order to test our hypothesis that vitamin D-deficient COPD patients would particularly benefit from vitamin D supplementation, we explored the association between pDES change during the course of the intervention period and baseline 25(OH)D levels. Whereas we had expected to find a positive association in the intervention arm between baseline serum 25(OH)D levels and pDES change, we found the opposite. It may suggest that higher serum 25(OH)D levels are needed to obtain any protective effect of vitamin supplementation on elastin degradation. Obviously, these 25(OH)D levels >50 ng.mL−1 were only reached in patients with normal baseline levels. Additional trials are therefore needed to clarify whether the inverse correlation between baseline 25(OH)D and pDES change is real.

There is an apparent paradox given that vitamin D supplementation decreased exacerbation frequency in vitamin D-deficient participants [1], whereas our post hoc analysis revealed that the intervention had accelerated elastin degradation in these subjects. We suspect that exogenous vitamin D might have both favourable and unfavourable effects in patients with COPD. The reducing effect on exacerbation frequency and elastin degradation is probably due to vitamin D's anti-inflammatory properties. The enhancing effect of vitamin D supplementation on elastin degradation might potentially be explained by a transient rise in calcium levels with bolus administration [13]. Intermittent high-dose bolus interventions result in a sharp rise in serum 25(OH)D levels to often supra-physiological concentrations at the time of administration [14], which have been associated with hypercalcaemia and even mortality [15, 16]. The buoyant effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation on elastin's calcium content is much more pronounced than the transient rise in blood calcium levels [17]. This phenomenon was demonstrated in rats treated with extremely high-dose vitamin D [17]. Aortic tissue calcium content was raised ∼15 times, whereas the calcium concentration in the rats' serum was minimally affected [17]. Vitamin D supplementation also caused >50% reduction of aortic DES content in this animal model, illustrating the close relationship between vitamin D, elastin calcification and elastin degradation [17]. The calcifying effect of extremely high-dose vitamin D is not unique to the vasculature. Tissue calcium levels in rats' lungs were also much higher in the vitamin D than in the control group [18]. The effect of vitamin D on elastin degradation in the lungs was unfortunately not assessed in this animal study [18]; however, we would expect a similar reduction of pulmonary DES levels. Although we did not observe a difference in serum calcium levels at any time during follow-up, a calcifying effect of transient elevation of serum calcium levels following vitamin D boluses may explain our negative observations as blood samples were collected independently from drug intake [13]. In addition to this, there are also reasons to assume that bolus administrations not only have more unfavourable effects, but also less favourable effects than daily vitamin D supplementation. In particular, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that the protective effect against infections was only obtained with daily dose interventions and not with pulses of vitamin D supplements [19]. Other studies with daily dose interventions in vitamin D-deficient COPD patients are warranted.

Interestingly, there is evidence to suggest that vitamin D and K may play synergistic roles in the prevention of elastin calcification and degradation [20]. Matrix Gla protein (MGP) is a potent inhibitor of elastin mineralisation and degradation which requires vitamin K for its activation [21]. A vitamin D-responsive element is found in the promoter of the MGP gene, which has the capacity to upregulate gene expression following vitamin D binding thereby increasing the demand for vitamin K to carboxylate the surplus inactive MGP [22]. Administration of vitamin D may have the potential to induce relative vitamin K deficiency through this mechanism [20]. Recent studies indeed show that vitamin D supplementation reduces vitamin K status [23, 24]. Survival is strongly reduced in kidney transplant recipients who are treated with active vitamin D with low versus high vitamin K status, which is most likely caused by calcifying effects of vitamin D on blood vessels unopposed by sufficient MGP that has been activated by vitamin K [24]. Furthermore, data from our group show the presence of an inverse association between vitamin K status and the rate of elastin degradation [25]. Although we did not assess vitamin K status in our study, it might be that vitamin D-deficient COPD patients also had low baseline vitamin K status and therefore experienced negative effects of vitamin D supplementation on elastin degradation. We hypothesise that vitamin K might potentially negate the alleged adverse effect of vitamin D administration on elastin calcification and degradation.

An interesting observation is the positive association between serum phosphate and pDES levels. Although this correlation should be replicated in an independent cohort before drawing any definitive conclusions, data are available that could potentially explain why phosphate might have an accelerating effect on elastin degradation. Hyperphosphataemia is a well-established risk factor of arterial calcification and mortality in patients with end-stage kidney disease [26]. However, a recent study demonstrated that higher serum phosphate levels are also strongly associated with increased mortality in patients with COPD [27]. Elastocalcinosis is characterised by the accumulation of calcium phosphate (i.e. hydroxyapatite) within the arterial wall. Whereas elastin with little hydroxyapatite is relatively resistant to elastases, the vulnerability to these degrading enzymes increases parallel to the increasing calcium phosphate content causing accelerated elastin degradation [28]. If the positive relationship between serum phosphate and pDES could be replicated, it would form the rationale for an intervention trial to assess the effect of phosphate-reducing interventions on disease progression and rates of elastin degradation in COPD.

One important limitation of our study is the low number of patients with normal to high baseline serum 25(OH)D levels. Interestingly, we observed a favourable pDES decrease during the course of the study in every subject from the intervention arm with a baseline serum 25(OH) level above 30 ng.mL−1. However, due to the paucity of these patients (only five in the intervention arm), we were missing adequate power to determine whether vitamin D supplementation in vitamin D-sufficient patients indeed decelerates elastin degradation. Another limitation may be found in the study population of tertiary care patients in which elastin degradation might be affected by many other factors, such as repeated exacerbations. Additional studies are therefore needed to assess the effects of vitamin D supplementation on pDES levels in a population-based COPD population.

In conclusion, we did not find an effect of serum 25(OH)D levels on the rate of elastin degradation in vitamin D-naïve patients. Contrary to our hypothesis, vitamin D supplementation seems to decelerate elastin degradation in vitamin D-sufficient COPD patients and not in vitamin D-deficient subjects.

Acknowledgements

Part of this article has been presented in abstract form at the European Respiratory Society International Congress on 6 September 2016 in London, UK. The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, were involved at all stages of manuscript development, and have approved the final version.

Footnotes

The original Leuven vitamin D intervention trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with identifier number NCT00666367.

Conflict of interest: R. Janssen has a patent, “Method and compositions to facilitate regeneration and repair of elastin fibers in lungs of patients with COPD” pending and is one of the owners of Desmosine.com (a company that measures the biomarker desmosine for biopharma companies and researchers).

Conflict of interest: J. Serré has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: I. Piscaer has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R. Zaal has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. van Daal has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Mathyssen has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: P. Zanen has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.M.W. van den Ouweland reports that he is one of the owners of Desmosine.com (a company that measures the biomarker desmosine for biopharma and researchers).

Conflict of interest: W. Janssens reports grants from the Flemish Research Funds (FWO) and the Belgian AstraZeneca chair in respiratory pathophysiology during the conduct of the study, and is cofounder of ArtIQ.

Support statement: The original Leuven vitamin D intervention trial was sponsored by the Applied Biomedical Research Program, Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology (IWT-TBM).

References

- 1.Lehouck A, Mathieu C, Carremans C, et al. High doses of vitamin D to reduce exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156: 105–114. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martineau AR, James WY, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D3 supplementation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ViDiCO): a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3: 120–130. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70255-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heulens N, Korf H, Cielen N, et al. Vitamin D deficiency exacerbates COPD-like characteristics in the lungs of cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Respir Res 2015; 16: 110. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0271-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holick MF. Vitamin D Physiology, Molecular Biology and Clinical Applications, Volume 1. 2nd Edn New York, NY, Humana Press, 2013; pp. 3–97. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssens W, Bouillon R, Claes B, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in COPD and correlates with variants in the vitamin D-binding gene. Thorax 2010; 65: 215–220. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.120659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D to prevent exacerbations of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised controlled trials. Thorax 2019; 74: 337–345. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mithieux SM, Weiss AS. Elastin. Adv Protein Chem 2005; 70: 437–461. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70013-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabinovich RA, Miller BE, Wrobel K, et al. Circulating desmosine levels do not predict emphysema progression but are associated with cardiovascular risk and mortality in COPD. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 1365–1373. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01824-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssens W, Decramer M, Mathieu C, et al. Vitamin D and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: hype or reality? Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 804–812. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70102-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma S, Lin YY, Turino GM. Measurements of desmosine and isodesmosine by mass spectrometry in COPD. Chest 2007; 131: 1363–1371. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma S, Turino GM, Hayashi T, et al. Stable deuterium internal standard for the isotope-dilution LC-MS/MS analysis of elastin degradation. Anal Biochem 2013; 440: 158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umeda H, Nkamura F, Suyama K. Oxodesmosine and isooxodesmosine, candidates of oxidative metabolic intermediates of pyridinium cross-links in elastin. Arch Biochem Biophys 2001; 385: 209–219. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cipriani C, Romagnoli E, Scillitani A, et al. Effect of a single dose of 600,000 IU of cholecalciferol on serum salciotropic hormones in young subjects with vitamin D deficiency: a prospective intervention study. J Clin Endocinol Metab 2010; 95: 4771–4777. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilahi M, Armas LA, Heaney RP. Pharmacokinetics of a single, large dose of cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87: 688–691. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martineau AR. Bolus-dose vitamin D and prevention of childhood pneumonia. Lancet 2012; 379: 1373–1375. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60405-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melamed ML, Michos ED, Post W, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 1629–1637. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niederhoffer N, Bobryshev YV, Lartaud-Idjouadiene I, et al. Aortic calcification produced by vitamin D3 plus nicotine. J Vasc Res 1997; 34: 386–398. doi: 10.1159/000159247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price PA, Buckley JR, Williamson MK. The amino bisphosphonate ibandronate prevents vitamin D toxicity and inhibits vitamin D-induced calcification of arteries, cartilage, lungs and kidneys in rats. J Nutr 2001; 131: 2910–2915. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.2910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: individual participant data meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess 2019; 23: 1–44. doi: 10.3310/hta23020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Ballegooijen AJ, Pilz S, Tomaschitz A, et al. The synergistic interplay between vitamins D and K for bone and cardiovascular health: a narrative review. Int J Endocrinol 2017; 2017: 7454376. doi: 10.1155/2017/7454376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schurgers LJ, Uitto J, Reutelingsperger CP. Vitamin K-dependent carboxylation of matrix Gla-protein: a crucial switch to control ectopic mineralization. Trends Mol Med 2013; 19: 217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser JD, Price PA. Induction of matrix Gla protein synthesis during prolonged 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment of osteosarcoma cells. Calcif Tissue Int 1990; 46: 270–279. doi: 10.1007/BF02555007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Ballegooijen AJ, Beulens JWJ, Schurgers LJ, et al. Effect of 6-month vitamin D supplementation on plasma matrix Gla protein in older adults. Nutrients 2019; 11: E231. doi: 10.3390/nu11020231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Ballegooijen AJ, Beulens JWJ, Keyzer CA, et al. Joint association of vitamins D and K status with long-term outcomes in stable kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 706–714. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piscaer I, van den Ouweland JMW, Vermeersch K, et al. Low vitamin K status is associated with increased elastin degradation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med 2019; 8: 1116. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hruska KA, Mathew S, Lund R. Hyperphosphatemia of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2008; 74: 148–157. 10.1038/ki.2008.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campos-Obando N, Lahousse L, Brusselle G. Serum phosphate levels are related to all-cause, cardiovascular and COPD mortality in men. Eur J Epidemiol 2018; 33: 859–871. 10.1007/s10654-018-0407-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basalyga DM, Simionescu DT, Xiong W. Elastin degradation and calcification in an abdominal aorta injury model. Circulation 2004; 110: 3480–3487. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148367.08413.E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]