Abstract

The stringent response is characterized by the synthesis of the alarmone (p)ppGpp. The phenotypic consequences resulting from (p)ppGpp accumulation vary among species, and for several pathogenic bacteria, it has been shown that the activation of the stringent response strongly affects biofilm formation and maintenance. In Staphylococcus aureus, (p)ppGpp can be synthesized by the RelA/SpoT homolog Rel upon amino acid deprivation or by the two small alarmone synthetases RelP and RelQ under cell wall stress. We found that relP and relQ increase biofilm formation under cell wall stress conditions induced by a subinhibitory vancomycin concentration. However, the effect of (p)ppGpp on biofilm formation is independent of the regulators CodY and Agr. Biofilms formed by the strain HG001 or its (p)ppGpp-defective mutants are mainly composed of extracellular DNA and proteins. Furthermore, the induction of the RelPQ-mediated stringent response contributes to biofilm-related antibiotic tolerance. The proposed (p)ppGpp-inhibiting peptide DJK-5 shows bactericidal and biofilm-inhibitory activity. However, a non-(p)ppGpp-producing strain is even more vulnerable to DJK-5. This strongly argues against the assumption that DJK-5 acts via (p)ppGpp inhibition. In summary, RelP and RelQ play a major role in biofilm formation and maintenance under cell wall stress conditions.

Keywords: stringent response, (p)ppGpp, biofilm, Staphylococcus aureus, cell wall stress

Introduction

Biofilms are sessile microbial communities attached to surfaces and embedded in an extracellular matrix. Biofilm-forming staphylococci cause many device-related or chronic infections (Kong et al., 2006; O’Gara, 2007; Speziale et al., 2014; Mccarthy et al., 2015; Paharik and Horswill, 2016; Figueiredo et al., 2017; Moormeier and Bayles, 2017; Arciola et al., 2018; Otto, 2018). Depending on the composition of the biofilm matrix, staphylococcal biofilms are classified as ica-dependent or ica-independent (O’Gara, 2007). Ica-dependent biofilms are characterized by polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) also known as poly-N-acetyl glucosamine (PNAG), which is synthesized by enzymes encoded by the icaADBC operon (Götz, 2002). In ica-independent biofilms, proteins (Speziale et al., 2014) and extracellular nucleic acids (eDNA) (Moormeier and Bayles, 2017) are the main matrix components. Biofilm formation is a three-step process that includes initial attachment to the surface, biofilm maturation due to intercellular aggregation and bacterial cell detachment. Detachment is mediated by the enzymatic degradation of matrix components by proteases, nucleases or a group of small amphiphilic α-helical peptides, known as phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) (Otto, 2018).

The nature and extent of biofilms are highly variable between different strains and growth conditions. Mounting evidence suggests that subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations can promote biofilm formation (Rachid et al., 2000; Kaplan et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2018; Ranieri et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2020) by inducing eDNA release and thus shifting the composition of the biofilm matrix toward a higher eDNA content (Brunskill and Bayles, 1996; Mlynek et al., 2016; Schilcher et al., 2016). Multiple regulatory mechanisms are involved in the molecular switch from a planktonic to a biofilm lifestyle, such as transcriptional regulation via SarA, SaeRS, CodY or the quorum-sensing system Agr (Kong et al., 2006; Boles and Horswill, 2008; Beenken et al., 2010; Stenz et al., 2011; Cue et al., 2012; Mrak et al., 2012; Abdelhady et al., 2014; Atwood et al., 2015; Paharik and Horswill, 2016).

For several bacterial species, it has been demonstrated that the activation of the stringent response also affects biofilm formation (Balzer and Mclean, 2002; Taylor et al., 2002; Lemos et al., 2004; Aberg et al., 2006; Chavez De Paz et al., 2012; He et al., 2012; Sugisaki et al., 2013; De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2014; Azriel et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016; Diaz-Salazar et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Colomer-Winter et al., 2018, 2019). The stringent response is characterized by the synthesis of guanosine-tetra-phosphate (ppGpp) and guanosine-penta-phosphate (pppGpp), collectively referred to as (p)ppGpp. The accumulation of (p)ppGpp affects gene expression, protein translation, enzyme activation and replication (Wu and Xie, 2009; Liu et al., 2015; Steinchen and Bange, 2016; Bennison et al., 2019). In many pathogenic bacteria, (p)ppGpp determines virulence or antibiotic tolerance/persistence (Dalebroux et al., 2010; Hauryliuk et al., 2015; Harms et al., 2016; Wood and Song, 2020). Staphylococcus aureus harbors three genes encoding (p)ppGpp synthetases, Rel, RelP, and RelQ (Wolz et al., 2010). The (p)ppGpp synthetase activity of the bifunctional Rel enzyme can be induced by tRNA-synthetase inhibitors such as mupirocin or serine-hydroxamate or by amino acid deprivation (Geiger et al., 2010). Rel usually shows strong hydrolase activity, which is essential to detoxify (p)ppGpp produced by RelP or RelQ (Gratani et al., 2018). RelP and RelQ only contain a synthase domain (Geiger et al., 2014) and are part of the VraRS cell wall stress regulon (Kuroda et al., 2003). Thus, they are transcriptionally induced (e.g., after vancomycin treatment) and contribute to tolerance toward cell wall-active antibiotics such as ampicillin or vancomycin (Geiger et al., 2014).

There is some evidence that the stringent response might trigger biofilm formation in S. aureus based on the observation that treatment with mupirocin (Sritharadol et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2020) or serine hydroxamate (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2014) results in increased biofilm formation. Moreover, the anti-biofilm peptides IDR-1018 and DJK-5 have been suggested to directly interact with (p)ppGpp, preventing its signaling effects and, thus, biofilm formation (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2014, 2015).

Here, we aimed to investigate the role of the stringent response mediated by the two small alarmone synthetases RelP and RelQ in biofilm formation. Under cell wall stress conditions induced by a subinhibitory vancomycin concentration, both RelP and RelQ are crucial for biofilm development. Moreover, (p)ppGpp synthesis prevents biofilm eradication by vancomycin. (p)ppGpp-mediated biofilm formation was shown to be independent of the major stringent response mediator CodY and the main biofilm regulator Agr. The anti-biofilm peptide DJK-5 could prevent biofilm formation of wild type and (p)ppGpp-defective mutants. However, the (p)ppGpp0 strain is even more vulnerable to DJK-5. Thus, DKJ-5 does not act on biofilm formation via (p)ppGpp inhibition.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. For overnight cultures, the strains were grown with appropriate antibiotics (10 μg/ml erythromycin, 100 μg/ml spectinomycin) at 37°C and 200 rpm. For biofilm analyses, the following media were used: chemically defined medium (CDM; Pohl et al., 2009), tryptic soy broth (TSB, Oxoid) with 3% NaCl and 0.5% glucose, and BM2 glucose [0.4% (w/v) glucose, 62 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 7 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 10 mM FeSO4, 0.5% casamino acids] (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2014).

Strain Construction

For relP complementation, the pCG833 plasmid was constructed. The complete relP operon with its native promoter was amplified by PCR using the primers pCG833gibfor and pCG833gibrev and cloned via Gibson assembly into the BamHI-digested integration vector pCG3. The oligonucleotides used in these procedures are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Due to showing toxicity in E. coli, the plasmid was directly transformed into S. aureus Cyl316 by electroporation. The integration of the plasmid into the genome was verified by PCR using the scv1, scv21, pCG3intfor and pCG3intrev oligonucleotides followed by sequencing. The integrated plasmid was transduced into the target strains using Φ11 phage.

For relQ complementation, the pCG216 plasmid was constructed. relQ with its native promoter was amplified by PCR with the primers BamHrelQkompl-for and BamHrelQkomp-rev and ligated with the BamHI-digested pCG3 vector backbone. The plasmid was verified by PCR with relQdigfor and relQdigrev. The plasmid was transformed into Cyl316 and verified by PCR using the primers relQfor and relQrev for integration of the plasmid. The integrated plasmid was then transduced via phage Φ11 in the target strains.

codY and agr mutations were transduced into the (p)ppGpp strain using the lysates of RN4220-21 (Pohl et al., 2009) and RN6911 (Kornblum et al., 1990), respectively.

Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) and Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination

For CFU measurements, biofilm-grown bacteria (24 h, 37°C) were resuspended by thorough pipetting. The bacterial suspension (biofilm resolved and planktonic) was serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 10 μl aliquots were spotted onto TSA plates for CFU determination. The MIC was determined by serial microdilution and E-tests.

Biofilm Assay

For the static biofilm assay, 1 ml medium was inoculated in a 24-well polystyrene cell culture plate (Greiner) to obtain an OD600 of 0.05. After 24 h of static incubation at 37°C, the wells were washed twice with 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, Gibco). The biofilm was dried at 40°C for 30 min. For biofilm staining, 200 μl of crystal violet (80 μg/ml in distilled water) was added to the wells, followed by incubation at RT for 5 min. The wells were then washed twice with 1 ml distilled water and dried at 40°C for 30 min. Biofilm quantification was performed by A600 determination (microplate reader, Tecan Infinite 200 and Tecan Spark). To account for the different distributions of biofilms within a single well, measurements were performed 100 times within one well, and the average was calculated. If required, a sub-inhibitory concentration of vancomycin (0.78 μg/ml) or 5 μg/ml of the anti-biofilm peptide DJK-5 (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2015) were added. To test the biofilm eradication capacity, preformed biofilms (37°C, 8 h) were incubated for an additional 16 h in the presence of vancomycin at concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 μg/ml. Biofilm staining and CFU determination were performed as described above.

Biofilm Composition

Biofilms were washed twice with PBS and treated with 1 mg/ml proteinase K (AppliChem, 37°C, 4 h), 0.1 mg/ml DNase (Sigma-Aldrich, 37°C, 4 h) or with 40 mM sodium periodate (NaIO4) (24 h, 4°C). The biofilms were then washed twice with PBS, dried and stained as described above.

Results

(p)ppGpp Synthetases Show no Significant Effect on Biofilm Formation Under Non-stress Conditions

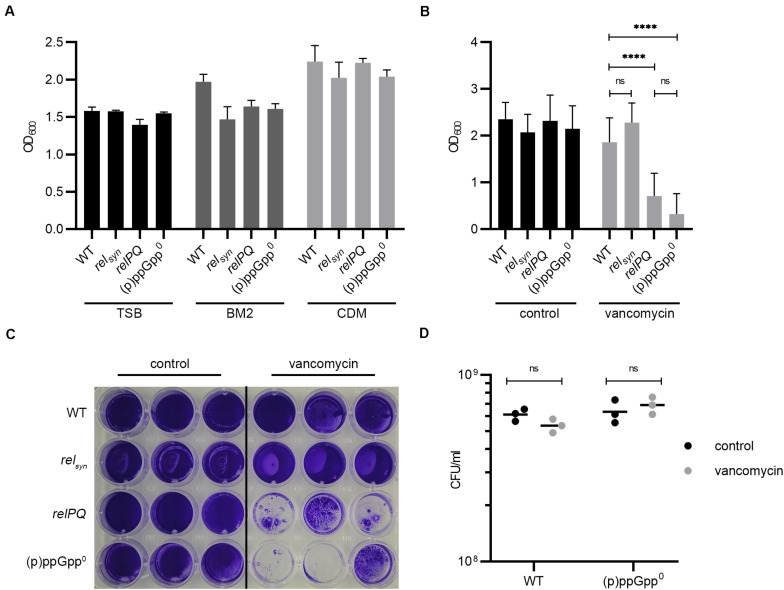

Recently, it was proposed that the stringent response facilitates biofilm formation in several pathogens, including S. aureus (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2014). However, basal medium 2 (BM2) used in this study allowed hardly any S. aureus growth, resulting in a final OD600 below 1 after overnight growth. Therefore, we first analyzed the impact of (p)ppGpp on biofilm formation using different media. These media included tryptic soy broth (TSB) with the addition of 0.5% glucose and 3% NaCl, which is widely used for S. aureus biofilm analyses (Lade et al., 2019), and CDM (Pohl et al., 2009), used to define the stringent response phenotype in S. aureus. For discrimination between the Rel- and RelP/RelQ-mediated stringent response, a relsyn mutant (mutation in the synthetase domain, leaving hydrolase activity unaltered), a relP, relQ double mutant and a (p)ppGpp0 mutant in which all three synthetases were non-functional were included in the analysis. Independent of the (p)ppGpp synthetases, all strains showed the strongest biofilm formation in CDM. Interestingly, in the prototypic biofilm medium TSB, biofilm formation was lower than in CDM (Figure 1A). However, no significant difference in biofilm formation was observed between the different strains in either medium. In BM2, a trend toward a slightly higher biofilm-forming capacity in the wild type compared to the mutant strains was observed, indicating that under these nutrient-limited conditions, the stringent response might be slightly activated. Thus, (p)ppGpp synthetases have no or little influence on the biofilm formation ability under non-stressed conditions.

FIGURE 1.

(p)ppGpp synthases effect biofilm formation under cell wall stress conditions. (A) Biofilm formation in TSB (+3% NaCl, +0.5% glucose), BM2 and CDM after 24 h. (B) Biofilm formation under uninduced and vancomycin-stress (subinhibitory vancomycin 0.78 μg/ml) conditions in CDM after 24 h. Three separate experiments were performed with biological triplicates each. Error bars represent the standard deviation, statistical significance based on ordinary one-way ANOVA (ns: not significant, ****: P < 0.0001). (C) Representative plate stained with crystal violet. (D) CFU was determined from resolved biofilm and planktonic bacteria after 24 h of static incubation.

RelP and RelQ Regulate Biofilm Formation Under Cell Wall Stress

Subinhibitory concentrations of vancomycin were shown to transcriptionally activate relP and relQ (Geiger et al., 2014). We thus speculated that the vancomycin-induced stringent response may interfere with biofilm formation. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) (1 μg/ml) of vancomycin in planktonically grown bacteria did not differ between the analyzed strains. At a subinhibitory concentration of vancomycin (0.78 μg/ml), the relPQ double mutant and the (p)ppGpp0 mutant showed significantly reduced biofilm formation compared to the wild type and the relsyn mutant (Figures 1B,C). Under vancomycin treatment, the wild type formed an almost uniform thick layer of biofilm. In contrast, the relPQ mutant and the (p)ppGpp0 strain showed significantly decreased biofilm formation, with some cell aggregates remaining after the washing procedure (Figures 1B,C). The bacterial survival of the tested strains was not impaired by the subinhibitory concentrations of vancomycin (Figure 1D). Thus, the RelP- and/or RelQ-dependent changes in biofilm formation were not due to growth inhibition or bacterial killing.

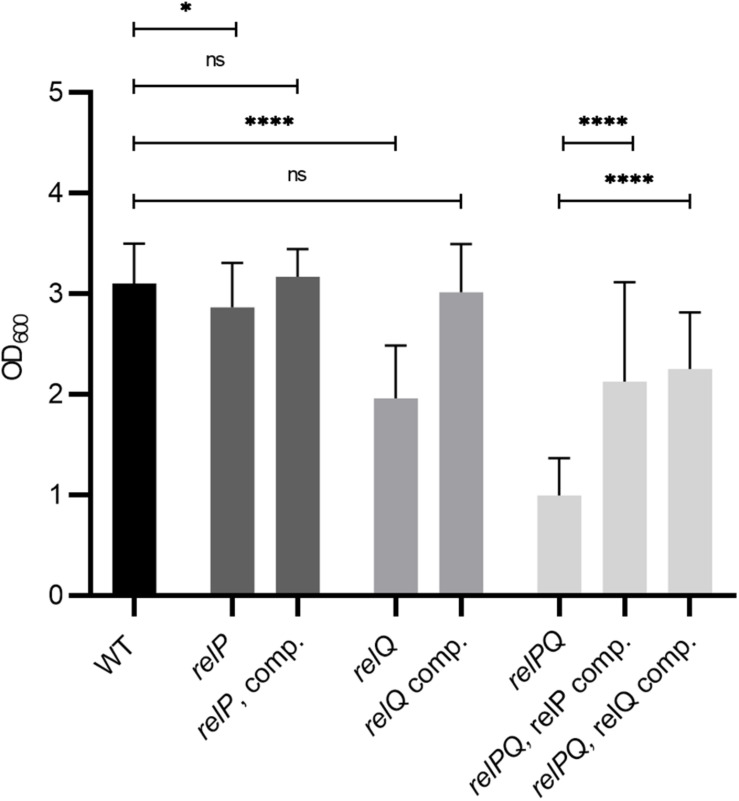

RelP and RelQ Synergistically Affect Biofilm Formation

To determine which of the synthetases impacts biofilm formation under vancomycin conditions, single relP and relQ mutants were analyzed. Both relP and relQ contributed to biofilm formation in the presence of vancomycin. They act synergistically, since the relPQ double mutant showed the lowest biofilm formation (Figure 2). The relPQ double mutant phenotype could be complemented by the integration of either relP or relQ into the chromosome (Figure 2). Thus, the vancomycin-dependent induction of either relP or relQ is sufficient to sustain S. aureus biofilm formation under cell wall stress conditions.

FIGURE 2.

RelP and RelQ affect biofilm formation synergistically. Biofilm formation under vancomycin-stress (0.78 μg/ml vancomycin) in CDM. Strains: HG001 wild type, relP and relQ single mutants, relPQ double mutant and complemented strains. Three separate experiments were performed with biological triplicates each. Error bars represent the standard deviation, statistical significance based on ordinary one-way ANOVA (ns: not significant, *: P < 0.1, ****: P < 0.0001).

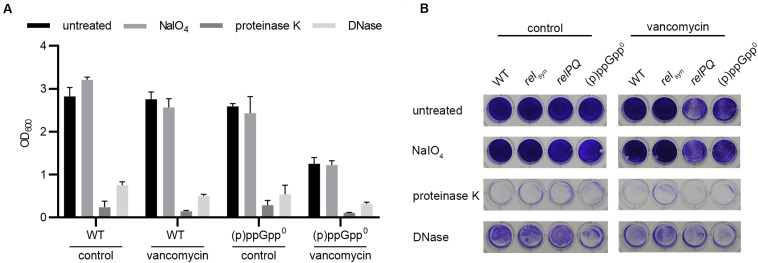

The Biofilm Composition Is Not Affected by the Stringent Response

The biofilm matrix is composed of PIA, proteins or eDNA (O’Gara, 2007; Paharik and Horswill, 2016). We analyzed which matrix components were involved in the observed RelP/Q-dependent biofilm alterations under vancomycin treatment. Preformed biofilms were treated with sodium periodate, proteinase K or DNase to selectively degrade PIA, proteins or eDNA matrix components, respectively (Seidl et al., 2008). Without vancomycin, the biofilms formed by the wild type or (p)ppGpp0 stain were almost completely degraded by proteinase K and DNase treatment, whereas sodium periodate had no effect on the biofilm matrix (Figures 3A,B). To ensure that vancomycin does not impact the biofilm composition, we additionally examined the matrix components after vancomycin treatment. Again, the biofilms consisted almost exclusively of proteins, and eDNA and sodium periodate treatment did not degrade the biofilm matrix. Thus, under the conditions applied here, HG001 forms ica-independent biofilms, and the biofilm composition is not altered by the stringent response.

FIGURE 3.

Biofilm composition is not affected by (p)ppGpp. (A) Preformed biofilms of the wild type and the isogenic (p)ppGpp0 strain were treated with either DNase or proteinase K for 4 h at 37°C or with sodium periodate for 24 h at 4°C. The remaining biofilm was stained with crystal violet and quantified by OD600 measurement. Three separate experiments were performed with biological triplicates each. Error bars represent the standard deviation. (B) Representative plate with wild type, relsyn, relPQ and the (p)ppGpp0 strain stained with crystal violet.

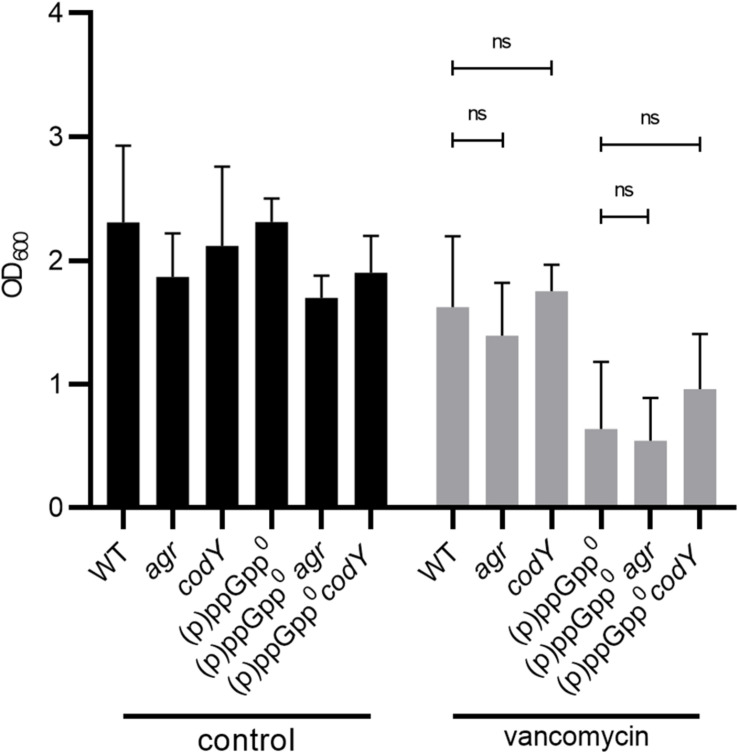

The Stringent Response Induces Biofilm Formation Independent of Agr and CodY

The quorum-sensing system Agr (especially the target genes psm) (Otto, 2018) and the transcriptional regulator CodY (Stenz et al., 2011) have been identified as key controllers of biofilm structure and detachment. (p)ppGpp synthesis results in the derepression of the CodY regulon and upregulation of Agr-dependent psm genes (Geiger et al., 2012). Thus, we hypothesized that Agr and/or CodY activity could interfere with the observed (p)ppGpp-dependent biofilm. However, the mutation of agr or codY did not impact biofilm formation (Figure 4). Thus, under our assay conditions, biofilm formation occurs independent of CodY or Agr. Strain specific effects of Agr (Yarwood et al., 2004) or CodY (Stenz et al., 2011) on biofilm formation were described previously.

FIGURE 4.

Biofilm formation under stringent conditions is independent of CodY and Agr. Biofilm formation under non-stressed and vancomycin-stress (0.78 μg/ml vancomycin) in CDM, 24 h. Three separate experiments were performed with biological triplicates each. Error bars represent the standard deviation, statistical significance based on ordinary one-way ANOVA (ns: P > 0.05).

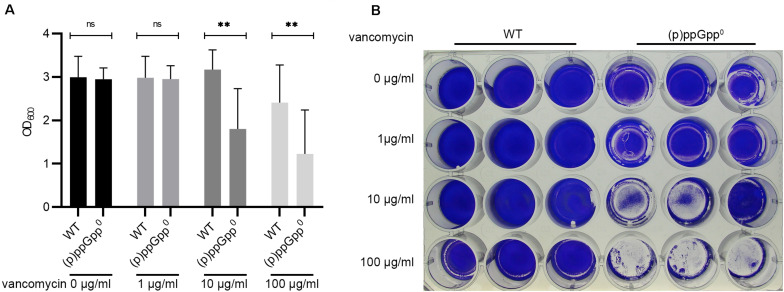

(p)ppGpp Contributes to Biofilm Antibiotic Tolerance

Biofilms are normally more tolerant to high concentrations of antibiotics than planktonic cultures. We hypothesized that the stringent response contributes to biofilm antibiotic tolerance in S. aureus. Therefore, biofilm antibiotic tolerance was compared between the wild type and the isogenic (p)ppGpp0 mutant. Preformed biofilms were exposed to increasing concentrations of vancomycin for 16 h. At the MIC (1 μg/ml for planktonically grown bacteria), vancomycin did not result in biofilm dispersal. However, at concentrations 10- and 100-fold higher than the MIC, the biofilm produced by the (p)ppGpp0 strain was significantly reduced, whereas the biofilm produced by the wild type was more resistant to vancomycin treatment (Figures 5A,B). Thus, (p)ppGpp contributes to biofilm-related antibiotic tolerance.

FIGURE 5.

(p)ppGpp contributes to biofilm related antibiotic tolerance. (A) Preformed biofilms (8 h) were exposed to increasing concentrations of vancomycin for 16 h. Three separate experiments were performed with biological triplicates each. Error bars represent the standard deviation, statistical significance based on ordinary one-way ANOVA (ns: not significant, **: P < 0.01). (B) Representative plate stained with crystal violet.

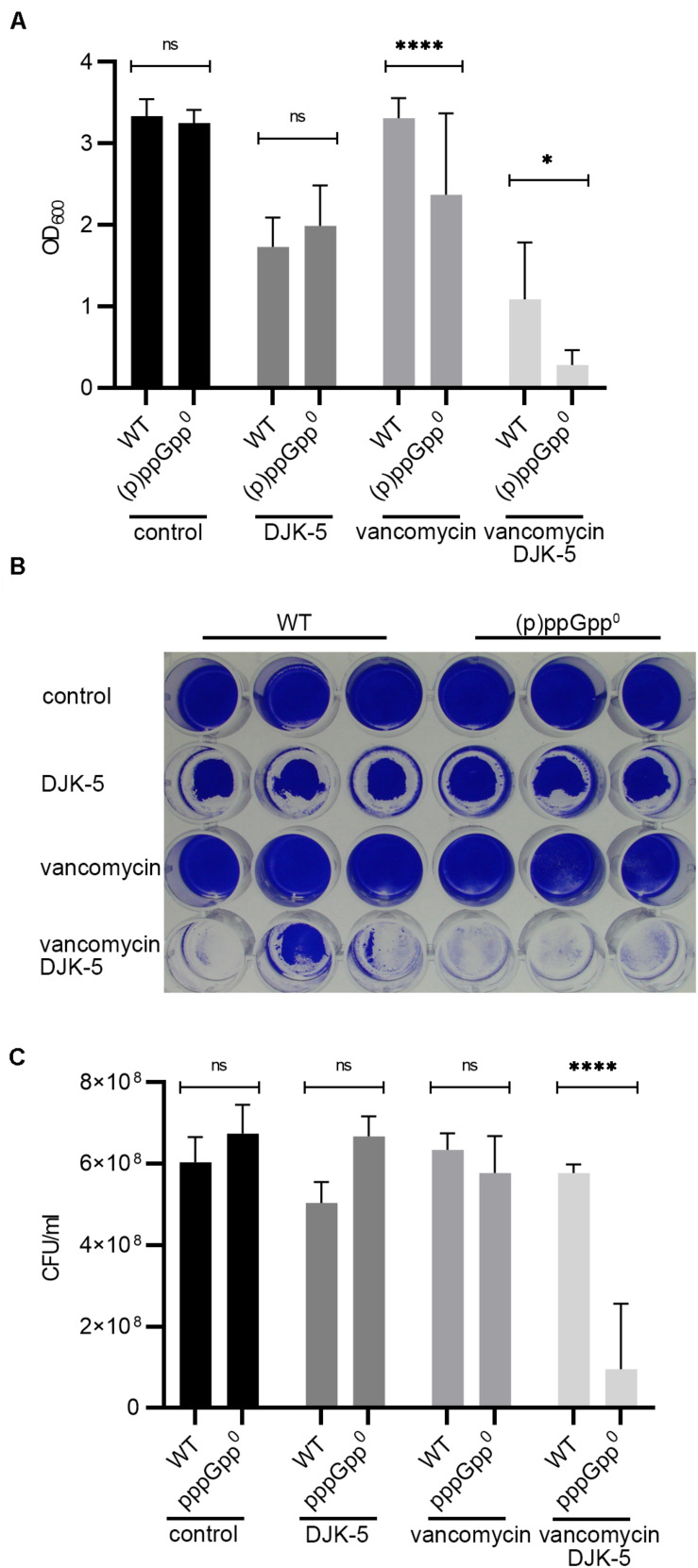

The Anti-Biofilm Peptide DJK-5 Exerts Its Effects Independent of (p)ppGpp

Recently, the peptides IDR-1018 (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2014) and DJK-5 (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2015) were proposed to prevent biofilms due to the specific targeting of intracellular (p)ppGpp. If correct, the peptides are expected to inhibit biofilm formation under stringent conditions in the wild type but not in the pppGpp0 background. We confirmed that DJK-5 interferes with biofilm formation in S. aureus (Figures 6A,B). However, without vancomycin treatment, biofilm formation by the wild type and pppGpp0 strains was equally affected by DJK-5, indicating that the effect was independent of (p)ppGpp. The combination of a subinhibitory vancomycin concentration and DJK-5 resulted in the complete inhibition of biofilm formation in the pppGpp0 strain. This can be explained by bacterial killing of the pppGpp0 strain through the synergistic action of vancomycin and DJK-5 (Figure 6C). Thus, (p)ppGpp synthesis in the wild type obviously protects the strain from the action of DJK-5. These findings are in contrast to the assumption that the biofilm-inhibiting activity of DJK-5 is exerted via (p)ppGpp inhibition, as proposed by De La Fuente-Nunez et al. (2014, 2015).

FIGURE 6.

DJK-5 interferes with biofilm formation under relaxed and stringent conditions. (A) Biofilms grown with or without vancomycin (0.78 μg/ml) and/or the anti-biofilm peptide DJK-5 (5 μg/ml) in CDM for 24 h. (B) Representative plate stained with crystal violet. (C) CFU of planktonic and biofilm bacteria determined in parallel after static growth for 24 h. Three separate experiments were performed with biological triplicates each. Error bars represent the standard deviation, statistical significance based on ordinary one-way ANOVA (ns: not significant, *: P < 0.1, ****: P < 0.0001).

Discussion

Here, we show that the small alarmone synthetases RelP and RelQ maintain the biofilm-forming capacity of S. aureus when exposed to subinhibitory concentrations of vancomycin. Both enzymes are part of the cell wall stress regulon and are transcriptionally induced by vancomycin (Geiger et al., 2014). They act synergistically, and the relPQ double mutant can be complemented via the chromosomal integration of either relP or relQ. Thus, the (p)ppGpp synthesis expected to occur upon vancomycin treatment supports biofilm growth, whereas without (p)ppGpp, no biofilms are formed in the presence of vancomycin. How (p)ppGpp promotes biofilm formation remains to be elucidated. (p)ppGpp results in an immediate decrease in intracellular GTP and derepression of the CodY regulon (Geiger et al., 2010). When CodY is loaded with GTP and/or branched-chain amino acids, it represses many metabolism-related genes, the Agr system and ica gene expression (Majerczyk et al., 2008; Pohl et al., 2009). The impact of CodY on biofilm formation is probably multifactorial and strain dependent (Stenz et al., 2011; Atwood et al., 2015). codY mutants have also been reported to aggregate, which can be linked with the interaction of PIA and eDNA on the bacterial surface (Mlynek et al., 2020). However, we can exclude the involvement of CodY regulation in the observed biofilm maintenance, since biofilm formation was not altered in a codY-negative background. Additionally, the Agr quorum-sensing system and, thus PSMs (which are strongly dependent on Agr activity), were excluded as mediators of the biofilm phenotype. Thus, the main mechanism for biofilm formation under vancomycin stress remains to be elucidated. (p)ppGpp dependent DNA-release by any of the lytic processes (e.g., autolysins, phages) likely contributes to biofilm formation. Recently, it was shown that mupirocin, a strong inducer of Rel-dependent (p)ppGpp synthesis, causes increased biofilm formation (Jin et al., 2020). Similar to our results, the mupirocin-induced biofilm forms independent of PIA and PSMs and is largely composed of eDNA. Thus, it is likely that the observed biofilm-inducing phenotype induced by mupirocin is similar to the vancomycin-dependent biofilm observed in our study. Jin et al. (2020) found that mupirocin upregulates cidA, encoding a holin-like protein, and that a cidA mutant shows reduced eDNA release. Thus, one may speculate that under our assay conditions, the (p)ppGpp-mediated activation of cidA may also contribute to (p)ppGpp-promoted biofilm formation.

The subinhibitory concentration of vancomycin applied in our standard biofilm assay did not affect bacterial viability, and the MIC in planktonically grown strains did not differ between the analyzed strains. When vancomycin was added to preformed biofilms, the biofilms were protected even at up to a concentration 100-fold higher than the MIC. It has been proposed that antibiotic tolerance and persister formation share common characteristics such as a slow- or non-growing phenotype (Waters et al., 2016). Here, we showed that biofilm tolerance is at least partly (p)ppGpp dependent, since biofilms of the pppGpp0 strain were significantly better resolved in the presence of high vancomycin concentrations. This seems to contrast with recent results indicating that (p)ppGpp is not involved in persister formation in S. aureus (Conlon et al., 2016). However, the persister assays were performed under relaxed conditions, and thus, the role of (p)ppGpp might have been missed. Nevertheless, (p)ppGpp synthesis was previously shown to contribute to antibiotic tolerance in S. aureus (Geiger et al., 2014; Bryson et al., 2020) and other pathogens (Nguyen et al., 2011; Bernier et al., 2013). Nguyen et al. (2011) suggested that in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the stringent response contributes to antimicrobial tolerance in biofilms by reducing oxidative stress. We recently showed that (p)ppGpp in S. aureus activates ROS-detoxifying systems (Horvatek et al., 2020), which might contribute to protection against vancomycin.

Due to the role of (p)ppGpp in biofilm formation and antibiotic tolerance, the (p)ppGpp synthesis pathway is thought to be a promising antimicrobial target. Anti-biofilm peptides have been reported to exert their activity via their ability to reduce (p)ppGpp levels in live bacterial cells (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2014, 2015). A direct mechanism of action involving the binding of (p)ppGpp and promotion of its intracellular degradation was suggested (De La Fuente-Nunez et al., 2015). We confirmed the biofilm-dissolving effect of DJK-5. However, this was clearly not due to the proposed interaction of the peptides with (p)ppGpp because an even stronger inhibitory effect of DJK-5 was observed in the (p)ppGpp0 mutant. Interestingly, treatment with DJK-5 and a subinhibitory vancomycin concentration resulted in significantly higher bacterial killing activity and biofilm inhibition in the (p)ppGpp0 mutant than the wild type. Thus, (p)ppGpp protects against bactericidal DJK-5 activity. These findings are in good agreement with a recent re-analysis of the proposed antibiofilm peptide IDR-1018 in E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Andresen et al., 2016). Genetic disruption of the relA and spoT genes responsible for (p)ppGpp synthesis moderately sensitizes E. coli to IDR-1018, rather than protecting the bacterium (Andresen et al., 2016). While the IDR-1018 and DJK-5 peptides are potent antimicrobials, they do not specifically disrupt biofilms via a direct and specific interaction with the intracellular messenger nucleotide (p)ppGpp. Their alternative mode of action remains to be elucidated.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in S. aureus, (p)ppGpp supports biofilm formation under cell wall stress conditions and increases tolerance against vancomycin and the anti-biofilm peptide DJK-5.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Isabell Samp and Natalya Korn for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Robert Hancock for providing DJK5.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by Grants from the “Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft”: TR34/B1 and SPP1879 to CW; stipend from the “Deutsches Zentrum für Infektionsforschung” to CK and Infrastructural funding from Cluster of Excellence EXC 2124 “Controlling Microbes to Fight Infections”.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.575882/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdelhady W., Bayer A. S., Seidl K., Moormeier D. E., Bayles K. W., Cheung A., et al. (2014). Impact of vancomycin on sarA-mediated biofilm formation: role in persistent endovascular infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 209 1231–1240. 10.1093/infdis/jiu007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberg A., Shingler V., Balsalobre C. (2006). (p)ppGpp regulates type 1 fimbriation of Escherichia coli by modulating the expression of the site-specific recombinase FimB. Mol. Microbiol. 60 1520–1533. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen L., Tenson T., Hauryliuk V. (2016). Cationic bactericidal peptide 1018 does not specifically target the stringent response alarmone (p)ppGpp. Sci. Rep. 6:36549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciola C. R., Campoccia D., Montanaro L. (2018). Implant infections: adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16 397–409. 10.1038/s41579-018-0019-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood D. N., Loughran A. J., Courtney A. P., Anthony A. C., Meeker D. G., Spencer H. J., et al. (2015). Comparative impact of diverse regulatory loci on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Microbiologyopen 4 436–451. 10.1002/mbo3.250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azriel S., Goren A., Rahav G., Gal-Mor O. (2016). The stringent response regulator DksA is required for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium growth in minimal medium, motility, biofilm formation, and intestinal colonization. Infect. Immun. 84 375–384. 10.1128/iai.01135-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer G. J., Mclean R. J. (2002). The stringent response genes relA and spoT are important for Escherichia coil biofilms under slow-growth conditions. Can. J. Microbiol. 48 675–680. 10.1139/w02-060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenken K. E., Mrak L. N., Griffin L. M., Zielinska A. K., Shaw L. N., Rice K. C., et al. (2010). Epistatic relationships between sarA and agr in Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS One 5:e10790. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennison J. B., Irving S. E., Corrigan R. M. (2019). The impact of the stringent response on TRAFAC GTPases and prokaryotic ribosome assembly. Cells 8:1313. 10.3390/cells8111313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier S. P., Lebeaux D., Defrancesco A. S., Valomon A., Soubigou G., Coppee J. Y., et al. (2013). Starvation, together with the SOS response, mediates high biofilm-specific tolerance to the fluoroquinolone ofloxacin. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003144. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles B. R., Horswill A. R. (2008). Agr-mediated dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000052. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill E. W., Bayles K. W. (1996). Identification and molecular characterization of a putative regulatory locus that affects autolysis in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 178 611–618. 10.1128/jb.178.3.611-618.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson D., Hettle A. G., Boraston A. B., Hobbs J. K. (2020). Clinical mutations that partially activate the stringent response confer multidrug tolerance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64 e02103-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez De Paz L. E., Lemos J. A., Wickstrom C., Sedgley C. M. (2012). Role of (p)ppGpp in biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 1627–1630. 10.1128/aem.07036-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer-Winter C., Flores-Mireles A. L., Kundra S., Hultgren S. J., Lemos J. A. (2019). (p)ppGpp and CodY promote Enterococcus faecalis virulence in a murine model of catheter-associated urinary tract infection. mSphere 4 e00392–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer-Winter C., Gaca A. O., Chuang-Smith O. N., Lemos J. A., Frank K. L. (2018). Basal levels of (p)ppGpp differentially affect the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis in Enterococcus faecalis. Microbiology 164 1254–1265. 10.1099/mic.0.000703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon B. P., Rowe S. E., Gandt A. B., Nuxoll A. S., Donegan N. P., Zalis E. A., et al. (2016). Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat. Microbiol. 1:16051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cue D., Lei M. G., Lee C. Y. (2012). Genetic regulation of the intercellular adhesion locus in staphylococci. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2:38. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalebroux Z. D., Svensson S. L., Gaynor E. C., Swanson M. S. (2010). ppGpp conjures bacterial virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74 171–199. 10.1128/mmbr.00046-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente-Nunez C., Reffuveille F., Haney E. F., Straus S. K., Hancock R. E. (2014). Broad-spectrum anti-biofilm peptide that targets a cellular stress response. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004152. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente-Nunez C., Reffuveille F., Mansour S. C., Reckseidler-Zenteno S. L., Hernandez D., Brackman G., et al. (2015). D-enantiomeric peptides that eradicate wild-type and multidrug-resistant biofilms and protect against lethal Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Chem. Biol. 22 196–205. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Salazar C., Calero P., Espinosa-Portero R., Jimenez-Fernandez A., Wirebrand L., Velasco-Dominguez M. G., et al. (2017). The stringent response promotes biofilm dispersal in Pseudomonas putida. Sci. Rep. 7:18055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo A. M. S., Ferreira F. A., Beltrame C. O., Cortes M. F. (2017). The role of biofilms in persistent infections and factors involved in ica-independent biofilm development and gene regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 43 602–620. 10.1080/1040841x.2017.1282941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T., Francois P., Liebeke M., Fraunholz M., Goerke C., Krismer B., et al. (2012). The stringent response of Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on survival after phagocytosis through the induction of intracellular PSMs expression. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003016. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T., Goerke C., Fritz M., Schafer T., Ohlsen K., Liebeke M., et al. (2010). Role of the (p)ppGpp synthase RSH, a RelA/SpoT homolog, in stringent response and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 78 1873–1883. 10.1128/iai.01439-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T., Kastle B., Gratani F. L., Goerke C., Wolz C. (2014). Two small (p)ppGpp synthases in Staphylococcus aureus mediate tolerance against cell envelope stress conditions. J. Bacteriol. 196 894–902. 10.1128/jb.01201-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz F. (2002). Staphylococcus and biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 43 1367–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratani F. L., Horvatek P., Geiger T., Borisova M., Mayer C., Grin I., et al. (2018). Regulation of the opposing (p)ppGpp synthetase and hydrolase activities in a bifunctional RelA/SpoT homologue from Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Genet. 14:e1007514. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms A., Maisonneuve E., Gerdes K. (2016). Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science 354:aaf4268. 10.1126/science.aaf4268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauryliuk V., Atkinson G. C., Murakami K. S., Tenson T., Gerdes K. (2015). Recent functional insights into the role of (p)ppGpp in bacterial physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13 298–309. 10.1038/nrmicro3448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Cooper J. N., Mishra A., Raskin D. M. (2012). Stringent response regulation of biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 194 2962–2972. 10.1128/jb.00014-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvatek P., Hanna A. M. F., Gratani F. L., Keinhörster D., Korn N., Borisova M., et al. (2020). Inducible expression of (pp) pGpp synthetases in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with activation of stress response genes. biorxiv [preprint]. 10.1101/2020.04.25.059725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Guo Y., Zhan Q., Shang Y., Qu D., Yu F. (2020). Sub-inhibitory concentrations of mupirocin stimulate Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation by up-regulating cidA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64 e01912-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan J. B., Izano E. A., Gopal P., Karwacki M. T., Kim S., Bose J. L., et al. (2012). Low levels of beta-lactam antibiotics induce extracellular DNA release and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. MBio 3 e00198-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong K. F., Vuong C., Otto M. (2006). Staphylococcus quorum sensing in biofilm formation and infection. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296 133–139. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblum J., Kreiswirth B. N., Projan S. J., Ross H. F., Novick R. P. (1990). “Agr: a polycistronic locus regulating exoprotein synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus,” in Molecular Biology of the Staphylococci, ed. Novick R. P. (New York, NY: VCH Publishers; ). [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M., Kuroda H., Oshima T., Takeuchi F., Mori H., Hiramatsu K. (2003). Two-component system VraSR positively modulates the regulation of cell wall biosynthesis pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 49 807–821. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lade H., Park J. H., Chung S. H., Kim I. H., Kim J. M., Joo H. S., et al. (2019). Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates is differentially affected by glucose and sodium chloride supplemented culture media. J. Clin. Med. 8:1853. 10.3390/jcm8111853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos J. A., Brown T. A., Jr., Burne R. A. (2004). Effects of RelA on key virulence properties of planktonic and biofilm populations of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 72 1431–1440. 10.1128/iai.72.3.1431-1440.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Xiao Y., Nie H., Huang Q., Chen W. (2017). Influence of (p)ppGpp on biofilm regulation in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Microbiol. Res. 204 1–8. 10.1016/j.micres.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yang L., Hou Y., Soteyome T., Zeng B., Su J., et al. (2018). Transcriptomics study on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm under low concentration of ampicillin. Front. Microbiol. 9:2413. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Bittner A. N., Wang J. D. (2015). Diversity in (p)ppGpp metabolism and effectors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 24 72–79. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majerczyk C. D., Sadykov M. R., Luong T. T., Lee C., Somerville G. A., Sonenshein A. L. (2008). Staphylococcus aureus CodY negatively regulates virulence gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 190 2257–2265. 10.1128/jb.01545-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccarthy H., Rudkin J. K., Black N. S., Gallagher L., O’neill E., O’gara J. P. (2015). Methicillin resistance and the biofilm phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 5:1. 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlynek K. D., Bulock L. L., Stone C. J., Curran L. J., Sadykov M. R., Bayles K. W., et al. (2020). Genetic and biochemical analysis of CodY-mediated cell aggregation in Staphylococcus aureus reveals an interaction between extracellular DNA and polysaccharide in the extracellular matrix. J. Bacteriol. 202 e00593-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlynek K. D., Callahan M. T., Shimkevitch A. V., Farmer J. T., Endres J. L., Marchand M., et al. (2016). Effects of low-dose amoxicillin on Staphylococcus aureus USA300 biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 2639–2651. 10.1128/aac.02070-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moormeier D. E., Bayles K. W. (2017). Staphylococcus aureus biofilm: a complex developmental organism. Mol. Microbiol. 104 365–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrak L. N., Zielinska A. K., Beenken K. E., Mrak I. N., Atwood D. N., Griffin L. M., et al. (2012). saeRS and sarA act synergistically to repress protease production and promote biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 7:e38453. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D., Joshi-Datar A., Lepine F., Bauerle E., Olakanmi O., Beer K., et al. (2011). Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science 334 982–986. 10.1126/science.1211037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Gara J. P. (2007). ica and beyond: biofilm mechanisms and regulation in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 270 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M. (2018). Staphylococcal biofilms. Microbiol. Spectr. 6:10.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paharik A. E., Horswill A. R. (2016). The staphylococcal biofilm: adhesins, regulation, and host response. Microbiol. Spectr. 4:10.1128. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl K., Francois P., Stenz L., Schlink F., Geiger T., Herbert S., et al. (2009). CodY in Staphylococcus aureus: a regulatory link between metabolism and virulence gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 191 2953–2963. 10.1128/jb.01492-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachid S., Ohlsen K., Witte W., Hacker J., Ziebuhr W. (2000). Effect of subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations on polysaccharide intercellular adhesin expression in biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44 3357–3363. 10.1128/aac.44.12.3357-3363.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri M. R., Whitchurch C. B., Burrows L. L. (2018). Mechanisms of biofilm stimulation by subinhibitory concentrations of antimicrobials. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 45 164–169. 10.1016/j.mib.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilcher K., Andreoni F., Dengler Haunreiter V., Seidl K., Hasse B., Zinkernagel A. S. (2016). Modulation of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm matrix by subinhibitory concentrations of clindamycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 5957–5967. 10.1128/aac.00463-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl K., Goerke C., Wolz C., Mack D., Berger-Bachi B., Bischoff M. (2008). Staphylococcus aureus CcpA affects biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 76 2044–2050. 10.1128/iai.00035-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speziale P., Pietrocola G., Foster T. J., Geoghegan J. A. (2014). Protein-based biofilm matrices in Staphylococci. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 4:171. 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sritharadol R., Hamada M., Kimura S., Ishii Y., Srichana T., Tateda K. (2018). Mupirocin at subinhibitory concentrations induces biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Drug Resist. 24 1249–1258. 10.1089/mdr.2017.0290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinchen W., Bange G. (2016). The magic dance of the alarmones (p)ppGpp. Mol. Microbiol. 101 531–544. 10.1111/mmi.13412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenz L., Francois P., Whiteson K., Wolz C., Linder P., Schrenzel J. (2011). The CodY pleiotropic repressor controls virulence in gram-positive pathogens. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 62 123–139. 10.1111/j.1574-695x.2011.00812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugisaki K., Hanawa T., Yonezawa H., Osaki T., Fukutomi T., Kawakami H., et al. (2013). Role of (p)ppGpp in biofilm formation and expression of filamentous structures in Bordetella pertussis. Microbiology 159 1379–1389. 10.1099/mic.0.066597-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. M., Beresford M., Epton H. A., Sigee D. C., Shama G., Andrew P. W., et al. (2002). Listeria monocytogenes relA and hpt mutants are impaired in surface-attached growth and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 184 621–628. 10.1128/jb.184.3.621-628.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E. M., Rowe S. E., O’gara J. P., Conlon B. P. (2016). Convergence of Staphylococcus aureus persister and biofilm research: can biofilms be defined as communities of adherent persister cells? PLoS Pathog. 12:e1006012. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolz C., Geiger T., Goerke C. (2010). The synthesis and function of the alarmone (p)ppGpp in firmicutes. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300 142–147. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood T. K., Song S. (2020). Forming and waking dormant cells: the ppGpp ribosome dimerization persister model. Biofilm 2:100018 10.1016/j.bioflm.2019.100018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Xie J. (2009). Magic spot: (p) ppGpp. J. Cell Physiol. 220 297–302. 10.1002/jcp.21797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Yu H., Zhang D., Xiong J., Qiu J., Xin R., et al. (2016). Role of ppGpp in Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute pulmonary infection and virulence regulation. Microbiol. Res. 192 84–95. 10.1016/j.micres.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarwood J. M., Bartels D. J., Volper E. M., Greenberg E. P. (2004). Quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 186 1838–1850. 10.1128/jb.186.6.1838-1850.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.