Highlights

-

•

This case report mainly focus on a case of 47-year old female with multinodular goiter.

-

•

Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology needs to be done from the suspicious nodule.

-

•

Toxic MNG is most effectively treated by total thyroidectomy, which achieves complete diminution from symptoms.

-

•

Surgery for huge goiter is challenging particularly on difficult intubation, altered anatomy, supraglottic edema and adhesions.

Keywords: Multinodular goiter, TSH, Thyroid, Total thyroidectomy

Abstract

Introduction

Toxic multinodular goiter (MNG) involves an enlarged thyroid gland, is a common cause of hyperthyroidism and when it is accompanied by obstructive symptoms such as dyspnea, it carries an indication for surgery.

Case presentation

We present a case of 47-year old female with multinodular goiter with a rapid increase in size within 2 years. She also reported palpitation, breathlessness on exertion, tachycardia and hand tremor. Computed tomography scan of the neck shows a gross enlargement of thyroid gland across both sides of the neck. The fine needle aspiration cytology and final histopathological examination were suggestive of MNG with adenomatous nodules and toxic changes respectively. A total thyroidectomy was performed and the gland was dissected successfully.

Discussion

Toxic MNG is most effectively treated by total thyroidectomy, which achieves complete diminution from symptoms.

Conclusion

Surgery for huge goiter is challenging and one should be careful about difficult intubation, altered anatomy and adhesions to the surrounding structures. Recognizing and treating this kind of cases are important, as they constitute a preventable cause of mortality if timely diagnosed and treated.

1. Introduction

Among the endocrine disorders, thyroid diseases are quite common and have a significant burden to many countries especially India [1]. Studies show that it has been estimated that about 32% are suffering in India [2]. Thyroid growth is dependent on thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), secreted by the pituitary gland and an enlarged thyroid gland is called a goiter. The TSH receptor agonists or antibodies stimulate the TSH receptors leading to diffuse goiter formation. A goiter is either diffusely enlarged or of nodular type. It can also be non-toxic (euthyroid), toxic (hyperthyroidism) or underactive (hypothyroidism). Increasing age, less iodine intake and exposure to external irradiation are the usual causative factors. Generally, nodular goiters are more common in women than in men [3]. Those with normal TSH levels, goiters may be asymptomatic, or it may be associated with systemic thyrotoxic symptoms (toxic MNG or Plummer's disease) [4]. Multinodular goiters (MNG) usually grow slowly, however, the enlargement of substernal MNG may cause mechanical compression of the trachea and esophagus causing dyspnea and dysphagia respectively. Either surgery or radioiodine treatment is strongly recommended for patients with toxic MNG [5]. Toxic nodular goiter can be a single toxic adenoma (single hyper-functioning nodule) within a multinodular thyroid or multiple hyperfunctioning nodules in the multinodular gland [6]. In this case report, we have diagnosed a patient with giant toxic MNG and mass effects, managed by total thyroidectomy. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [7].

2. Case report

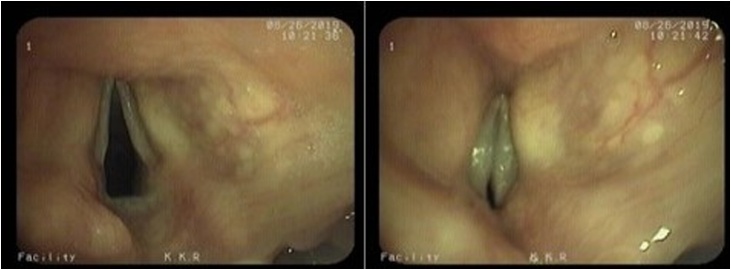

A 47-year-old female with long-standing neck swelling and dyspnea had been diagnosed as a case of toxic MNG and was on treatment for hyperthyroidism for the past 10 years elsewhere. She had Type II Diabetes Mellitus and hypertension for 5 years, which were under good control with medications. The size of the neck swelling was increasing gradually but the patient complained about the rapid increase in size for the past 2 years (Fig. 1). She complained of palpitation and breathlessness on exertion and was dyspnoeic on examination. Tachycardia and hand tremors were present on examination. There was no dysphagia or change in voice on presentation. Laryngoscopy conducted preoperatively showed supraglottic edema (Fig. 2a) and tracheal compression (Fig. 2b) with normal vocal cord mobility. She was referred to an Endocrinologist to treat her hyperthyroid state. Thyroid function test was conducted and showed normal levels at the time of surgery.

Fig. 1.

Shows the huge thyroid swelling with anterior and lateral views.

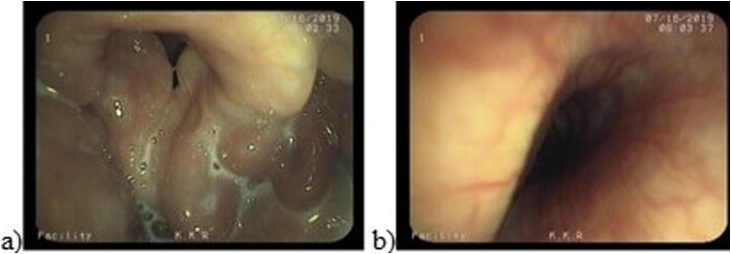

Fig. 2.

Shows preoperative video laryngoscopy shows supraglottic edema (a) and tracheal compression (b) of the patient.

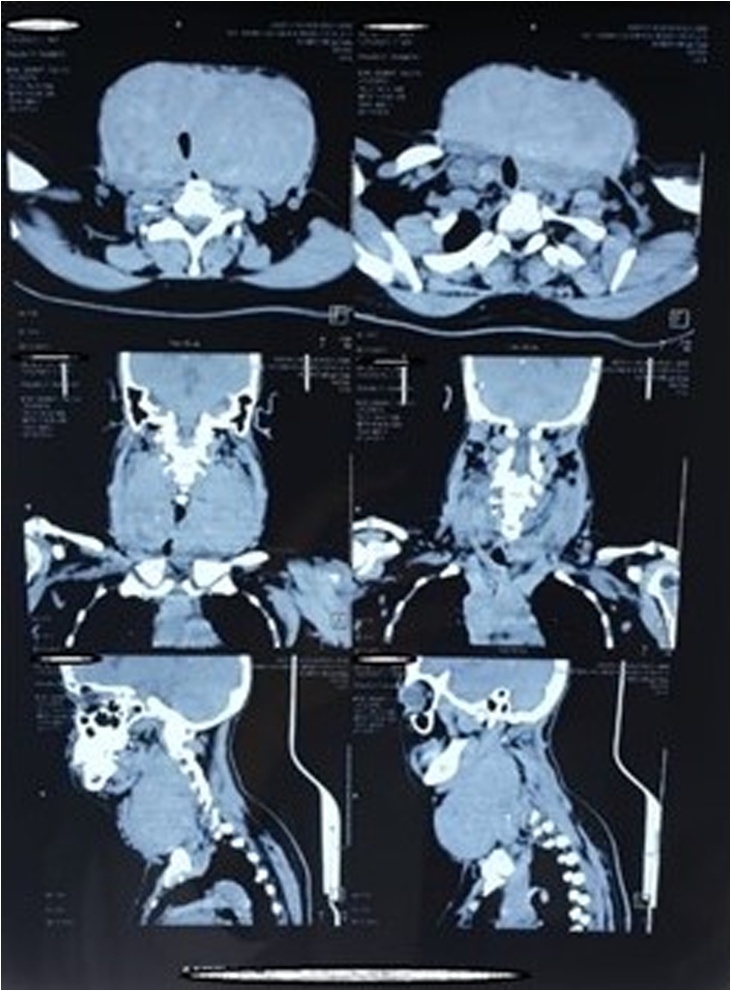

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography on the neck was done suggestive of gross enlargement of thyroid gland across both sides of the neck (more on the left side) (Fig. 3). Right lobe measures approximately 9.6 × 5.8 × 6 cms and left lobe measures approximately 9.5 × 8 × 8 cms (Fig. 3). The carotid vessels and internal jugular vein were displaced posterolaterally by the enlarged thyroid gland. The trachea appears compressed by the enlarged gland and there was no retrosternal extension or extracapsular extension seen. The fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) report was suggestive of MNG with adenomatous nodules. Final histopathological examination was suggestive of MNG with toxic changes.

Fig. 3.

Shows Computed Tomography of the Neck with thyroid swelling more on the left with tracheal compression and no retrosternal or extracapsular extension. It also shows the displacement of the internal jugular vein and carotid posterolaterally.

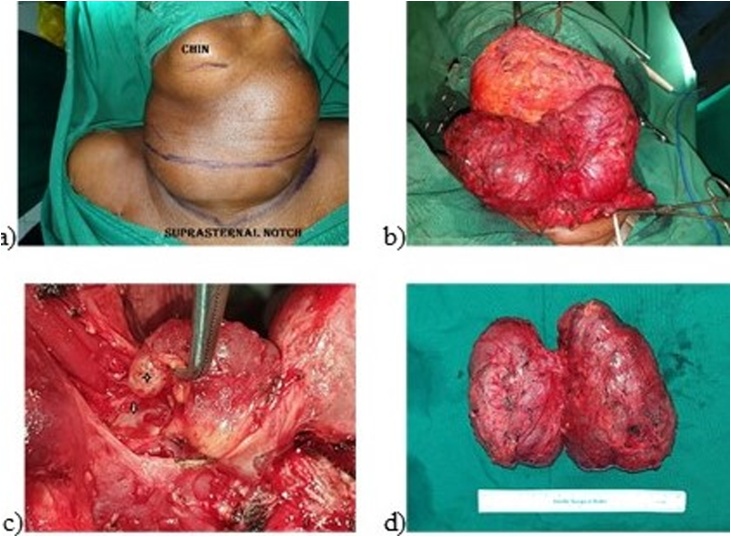

Total thyroidectomy was done under general anaesthesia. A horizontal neck incision was given over the neck swelling extending bilaterally up to the mastoid tip (Fig. 4). Strap muscles and sternocleidomastoid muscles were thinned out and were adhered with the thyroid. Strap muscles and Sternocleidomastoid muscles were cut for better exposure, and then resuturing was done at the end of surgery. Bilateral Internal jugular vein (IJV) and Carotid vessels were displaced posterolaterally and both IJV were compressed. Both side IJV and carotid vessels were identified, dissected out from the specimen and preserved. Both the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN) could not be preserved and sacrificed. Bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) were identified in Beahr’s triangle and dissected out from the specimen and preserved. Bilateral RLN adhered with the thyroid and both sides inferior parathyroid were identified and preserved. The pyramidal lobe of thyroid was enlarged and seen extending into the pre-epiglottic space and excised along with the specimen and there was no breach in the mucosal lining of larynx or pharynx. Bilaterally 14Fr romovac suction drain kept into the wound and wound repaired in layers. The patient was not extubated immediately for the fear of airway oedema.

Fig. 4.

Shows intraoperative findings – a) Horizontal neck Incision b) Exposure of the gland c) Extension of pyramidal lobe into the pre-epiglottic space, d) Specimen after removal.

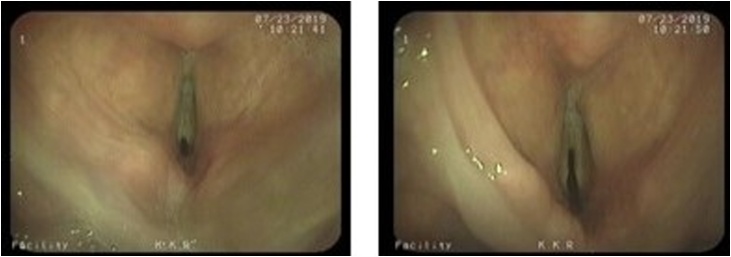

The patient was extubated on the next day and she was maintaining oxygen saturation around 95%. Her voice was breathy and in the evening of the postoperative day-1, the patient was desaturated and was unable to breathe, hence emergency tracheostomy was done. Laryngoscopy was conducted and diagnosis of bilateral vocal cord abductor paresis was made (Fig. 5). Ryle’s tube feeding was started since the patient had aspiration. On postoperative day-3, the patient developed hypocalcemia, hence calcium gluconate was given. Both drains were removed on postoperative day-6. A hole was made in the portex tracheostomy tube for speech. On postoperative day-20 tracheostomy tube was removed and the patient was able to take feed through the mouth and gradually the patient’s voice was improved to normal.

Fig. 5.

Shows a postoperative day 1 video laryngoscopy suggestive of bilateral abductor paresis.

3. Discussion

Most of the patients develop MNG due to iodine deficiency (endemic goiter) or by medication, growth-stimulating antibodies, and inherited defects in thyroid hormone synthesis [8]. Many patients present with huge thyroid enlargement resulting in pressure symptoms like dyspnea and dysphagia. The patients having hypothyroid MNG, levothyroxine is recommended to suppress TSH level [9] which acts as a growth factor for thyroid epithelial cells. Although some studies favour this TSH suppressive therapy, others have raised a question on the efficacy of treatment [10] and deleterious effects of subclinical hyperthyroidism. Radioiodine therapy is effectively used in toxic MNG resulting in improvement of pressure symptoms in the majority of patients. However, the medical therapy needs to be continued for several months for better improvement [11]. The radioactive iodine (I131) therapy is successful in 85–90% of graves cases [12]. Although it is extensively used for the treatment of toxic MNG, surgery is considered for patients with euthyroid, large, obstructive and toxic MNG [13]. Surgery may vary from lobectomy (solitary toxic nodule) to subtotal, near-total or total thyroidectomy (toxic MNG or grave’s disease). The total thyroidectomy is strongly recommended for toxic MNG as it is rapid, reliable, removes any coexisting malignancy and requires no-retreatment [14]. The patients with goiter should undergo TSH measurement and ultrasound of the neck to find out the functional status of the thyroid and any suspicious nodule for carcinoma and FNAC needs to be done from the suspicious nodule [15].

Here, in this case report, we presented a patient with huge goiter, which was compressing the trachea and was causing supraglottic edema and dyspnea. Although she was a known case of toxic MNG, her thyroid function test was normal because of medical treatment with carbimazole. Because of huge goiter and supraglottic edema intubation was very difficult and because of midline neck swelling, tracheostomy was not possible and hence bronchoscopic intubation was done.

Total thyroidectomy was done using a nerve monitor, although bilateral RLN was identified and preserved intraoperatively and nerve monitor was showing normal bilateral RLN function at the end of the surgery, the patient developed bilateral abductor vocal cord paresis (neuropraxia) on postoperative day-1, after approximately 7–8 h of extubation. Emergency tracheostomy was conducted for the patient and was removed after 20 days. The vocal cord functions returned to normal after a month (Fig. 6), favouring the diagnosis of bilateral RLN paresis. Incidences of RLN paresis (5.8%) and paralysis (1–2%) have been reported in the literature [16,17]. If there are unilateral RLN paraesis, the patient should be observed for 6–12 months before advocating any definitive treatment [18], because, the spontaneously favourable outcome may occur in that period. Even though bilateral inferior parathyroid glands were identified and preserved, hypocalcemia was noted postoperatively and managed with injection calcium gluconate initially. Calcium and vitamin D3 was provided at the later stage. Temporary hypoparathyroidism is usually seen in 8–10% of the population postoperatively [19]. Intraoperatively enlarged pyramidal lobe was seen entering into pre-epiglottic space but there was no breach in the laryngeal or pharyngeal mucosa. Studies show that 12% of the patients have pyramidal lobe [20]. The supraglottic edema subsided on the next day of surgery may be because of relieving pressure due to pyramidal lobe excision or due to use of steroids intraoperatively and postoperatively or because of both. Toxic MNG is most effectively treated by total thyroidectomy, which achieves complete diminution from symptoms (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Shows postoperative video laryngoscopy after 1 month with normal vocal cord mobility.

Fig. 7.

Shows a one-month postoperative clinical picture.

4. Conclusion

Surgery for huge goiter is challenging and one should be careful about difficult intubation, altered anatomy, supraglottic edema and adhesions to the surrounding structures. A pyramidal lobe may be present and may enter into pre-epiglottic space. The patient may also develop bilateral vocal cord paresis leading to emergency tracheostomy even when bilateral RLN was identified and preserved by using a nerve monitor.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval was exempted as the case reports do not require.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author’s contribution

SA has written the manuscript and reported the case. SPS designed the case report. RR and KKR are the surgeons and supervised. All the authors contributed to designing the study, writing the draft and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Registration of research studies

NA.

Guarantor

Ravi Ramalingam - Corresponding author.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Unnikrishnan A.G., Menon U.V. Thyroid disorders in India: an epidemiological perspective. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;15:S78–S81. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.83329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurya H. Thyroid function disorders among the Indian population. Ann. Thyroid Res. 2018;4:172–173. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popoveniuc G., Jonklaas J. Thyroid nodules. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2012;96(2):329–349. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearce E.N. Diagnosis and management of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ. 2006;332:1369–1373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7554.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanning E., Inder W.J., Mackenzie E. Radioiodine treatment for graves’ disease: a 10-year Australian cohort study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2018;18:94. doi: 10.1186/s12902-018-0322-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper D.S. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet. 2003;362:459–468. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham D., Singh N., Lang B. Benign nodular goitre presenting as acute airway obstruction. ANZ J. Surg. 2007;77:364–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roos A., Linn-Rasker S.P., van Domburg R.T., Tijssen J.P., Berghout A. The starting dose of levothyroxine in primary hypothyroidism treatment: a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005;165:1714–1720. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro M.R., Caraballo P.J., Morris J.C. Effectiveness of thyroid hormone suppressive therapy in benign solitary thyroid nodules: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:4154–4159. doi: 10.1210/jc.2001-011762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross D.S. Radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:542–550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1007101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mumtaz M., Lin L.S., Hui K.C., Mohd Khir A.S. Radioiodine I-131 for the therapy of graves’ disease. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2009;16:25–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rios A., Rodríguez J.M., Balsalobre M.D., Torregrosa N.M., Tebar F.J., Parrilla P. Results of surgery for toxic multinodular goiter. Surg. Today. 2005;35:901–906. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-3051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pisanu A., Montisci A., Cois A., Uccheddu A. Surgical indications for toxic multinodular goitre. Chir. Ital. 2005;57:597–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajmanoochehri F., Rabiee E. FNAC accuracy in diagnosis of thyroid neoplasms considering all diagnostic categories of the Bethesda reporting system: a single-institute experience. J. Cytol. 2015;32:238–243. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.171234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heikkinen M., Mäkinen K., Penttila E. Incidence, risk factors, and natural outcome of vocal fold paresis in 920 thyroid operations with routine pre- and postoperative laryngoscopic evaluation. World J. Surg. 2019;43:2228–2234. doi: 10.1007/s00268-019-05021-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang W., Chen D., Chen S., Li D., Li M., Xia S. Laryngeal reinnervation using ansa cervicalis for thyroid surgery-related unilateral vocal fold paralysis: a long-term outcome analysis of 237 cases. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karamanakos S.N., Markou K.B., Panagopoulos K. Complications and risk factors related to the extent of surgery in thyroidectomy. Results from 2,043 procedures. Hormones. 2010;9:318–325. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang Y.K., Lang B.H.H. To identify or not to identify parathyroid glands during total thyroidectomy. Gland Surg. 2017;6:20–29. doi: 10.21037/gs.2017.06.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geraci G., Pisello F., Li Volsi F., Modica G., Sciumè C. The importance of pyramidal lobe in thyroid surgery. G. Chir. 2008;29:479–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]