ABSTRACT

Movement disorders often emerge from the interplay of complex pathophysiological processes involving the kidneys and the nervous system. Tremor, myoclonus, ataxia, chorea, and parkinsonism can occur in the context of renal dysfunction (azotemia and electrolyte abnormalities) or they can be part of complications of its management (dialysis and renal transplantation). On the other hand, myoglobinuria from rhabdomyolysis in status dystonicus and certain drugs used in the management of movement disorders can cause nephrotoxicity. Distinct from these well‐recognized associations, it is important to appreciate that there are several inherited and acquired disorders in which movement abnormalities do not occur as a consequence of renal dysfunction or vice versa but are manifestations of common pathophysiological processes affecting the nervous system and the kidneys. These disorders are the emphasis of this review. Increasing awareness of these conditions among neurologists may help them to identify renal involvement earlier, take timely intervention by anticipating complications and focus on therapies targeting common mechanisms in addition to symptomatic management of movement disorders. Recognition of renal impairment in a patient with complex neurological presentation may narrow down the differentials and aid in reaching a definite diagnosis.

Keywords: movement disorders, nephropathy, neurogenetics.

The relationship between movement disorders and renal diseases is complex and multifaceted. Movement disorders can occur as manifestations of azotemia (uremic encephalopathy, uremic striatopallidal syndrome, and restless leg syndrome), manifestations of electrolyte abnormalities arising out of renal dysfunction, consequences of complications arising from dialysis (dialysis disequilibrium syndrome, osmotic demyelination syndrome, thiamine deficiency, and aluminum toxicity), consequences of complications arising from renal transplantation (immunosuppression‐related infections and neoplasia of the central nervous system), and manifestations of drug toxicity in the setting of renal dysfunction. Alternatively, renal dysfunction can be caused by some movement disorders (myoglobinuria in status dystonicus and neuroleptic malignant syndrome) and their management (retroperitoneal fibrosis induced by bromocriptine and other ergot derivatives). Finally, both the kidneys and the nervous system can be affected by common pathophysiological processes, which may be inherited or acquired.

In this educational review, our focus is on important inherited and acquired disorders manifesting with movement disorders and renal dysfunction. We lay out phenomenology of movement abnormalities and salient renal features of each of these. The classification of inherited disorders adopted here is based on predominant pathophysiology; it should be noted that mechanisms of neurological and renal involvement can be diverse and overlapping. For additional details on the inherited disorders, please refer to Tables 1, 2, and 3. The manifestations of renal dysfunction are depicted in Figures 1 and 2. The emphasis of this review is on inherited disorders manifesting renal glomerular or tubular dysfunction rather than disorders with structural changes such as cysts or neoplasia as seen, for example, in von Hippel–Lindau disease. Tables 4 and 5 briefly summarize the movement disorders caused by azotemia, electrolyte abnormalities, and complications of dialysis and renal transplantation; readers are directed to excellent reviews on this topic for more information. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Finally, renal complications attributed to movement disorders and their treatment are summarized in Table S1.

TABLE 1.

Inherited lysosomal and mitochondrial disorders with movement abnormalities and renal involvement

| Disorder (Gene) and Movement Abnormalities | Other Neurological Features | Renal Phenotype* and Other Systemic Features | Additional Features and Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysosomal disorders | |||

| Action myoclonus renal failure syndrome (SCARB2)Myoclonus (cortical), tremor, cerebellar ataxia 6 | Seizures, slow horizontal saccades, sensorineural hearing loss, peripheral neuropathy (usually subclinical, demyelinating) 7 , 8 , 9 | Renal phenotype: glomerulopathy; Other features: dilated cardiomyopathy 10 | AOO: adolescence, adulthood; Tremor is likely rhythmic cortical myoclonus; Atypical: prominent cognitive decline 11 ; MRI: usually normalEEG: generalized spike and wave discharges with background slowing |

| Anderson‐Fabry disease (GLA)Parkinsonism, 12 reduced hand dexterity, gait disturbances 13 | Neuropathic pain, transient ischemic attack or stroke, sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus 14 | Renal phenotype: glomerulopathy; Other features: angiokeratoma, cornea verticillata, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias 14 | AOO: variable; Parkinsonism is due to basal ganglia infarcts 12 ; Enzyme replacement therapy may slow progression of renal disease |

| Mitochondrial cytopathies | |||

| Kearns‐Sayre syndrome (large‐scale deletions or duplications in mtDNA)Cerebellar ataxia | Progressive external ophthalmoplegia, pigmentary retinopathy, sensorineural hearing loss, myopathy 15 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: diabetes mellitus, short stature 15 | AOO: childhood, adolescence; Tubulopathy can be presenting feature 16 ; MRI: cerebellar or global atrophy, T2W hyperintensities in the deep gray matter nuclei, cerebellar white matter, subcortical white matter 15 ; Muscle biopsy: ragged‐red fibers; CSF protein >100 mg/dL |

| Pearson syndrome (large scale deletions or duplications in mtDNA)Cerebellar ataxia | Progressive external ophthalmoplegia, pigmentary retinopathy, sensorineural hearing loss, myopathy 17 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: sideroblastic anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, life‐threatening exocrine pancreatic dysfunction 17 | AOO: childhood; Survivors may develop features of Kearns‐Sayre syndrome 17 |

|

Leigh syndrome (several genes for mitochondrial respiratory chain subunits) Dystonia (most common), ataxia, chorea, ballism, athetosis, myoclonus, parkinsonism |

Subacute psychomotor retardation, dysarthria, ophthalmoparesis, abnormal respiration, seizures, optic atrophy, retinopathy 18 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: short stature, anorexia, diarrhea, pancreatitis, cardiomyopathy, dysmorphic features | AOO: childhood, adolescence, adulthood; MRI: bilateral symmetric T2W hyperintensities in basal ganglia, thalamus, substantia nigra, brainstem, and spinal cord 18 |

| Myoclonic epilepsy with ragged‐red fibers (MT‐TK, MT‐TL1, MT‐TH, MT‐TS1)Myoclonus (cortical), cerebellar ataxia | Sensorineural hearing loss, optic atrophy, retinopathy, myopathy, exercise intolerance, peripheral neuropathy, cognitive decline 15 , 19 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: multiple lipomas | AOO: childhood, adolescence; MRI: cerebellar or brainstem atrophy 15 ; EEG: generalized spike and wave discharges with background slowing 19 ; Muscle biopsy: ragged‐ red fibers |

| Neurogenic muscle weakness, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa (MT‐ATP6)Cerebellar ataxia | Sensory neuropathy, retinitis pigmentosa, proximal muscle weakness (neurogenic); developmental delay, cognitive decline, seizures 15 | Renal phenotype: mixed glomerulopathy and tubulopathy 20 | AOO: adolescence, adulthood; Maternally inherited Leigh syndrome can occur in other family members if heteroplasmy level is >90% |

| Mitochondrial cerebellar ataxia, renal failure, and encephalopathy (MT‐ND5)Cerebellar ataxia | Peripheral neuropathy, sensorineural hearing loss 21 | Renal phenotype: glomerulopathy | AOO: adulthood; MRI: cerebellar atrophy 21 |

|

CoQ10 deficiency (COQ2, COQ6, PDSS2, COQ9) Cerebellar ataxia, dystonia |

Pyramidal signs, myopathy, seizures, intellectual disability, encephalopathy 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 | Renal phenotype: glomerulopathy (COQ2, COQ6, PDSS2) or tubulopathy (COQ9)Other features: fatal multisystem disorder in infants (severe phenotype) | AOO: childhood; Phenotypes: cerebellar ataxia, encephalomyopathy, Leigh syndrome; MRI: T2W hyperintensities in basal ganglia and white matter, 22 cerebellar and cortical atrophy 22 , 26 |

Abbreviations: AOO, age of onset; CoQ10, coenzyme Q10; EEG, electroencephalography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; T2W, T2‐weighted.

Predominant renal phenotype is mentioned; long‐standing glomerulopathy is accompanied by tubular dysfunction and atrophy.

TABLE 2.

Inherited organic acidurias, urea cycle disorders, and other metabolic disorders with movement abnormalities and renal involvement

| Disorder (Gene) and Movement Abnormalities | Other Neurological Features | Renal Phenotype* and Other Systemic Features | Additional Features and Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic acidurias | |||

|

Glutaric aciduria type 1 (GCDH) Dystonia, parkinsonism, chorea, athetosis |

Macrocephaly, acute encephalopathic crises, seizures, developmental delay, intellectual disability, subdural hematoma, retinal hemorrhage 27 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy a | AOO: childhood; MRI: widened Sylvian fissures with dilatation of the subarachnoid spaces surrounding underdeveloped frontotemporal lobes, subdural collections, T2W hyperintensities in globus pallidus, striatum, and white matter 28 |

|

Methylmalonic aciduria (MMUT, MMAA, MMAB, MMADHC) |

Encephalopathy (during metabolic crises), hypotonia, developmental delay, intellectual disability, seizures, optic atrophy, sensorineural hearing loss, supranuclear gaze palsy 31 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: pancreatitis, recurrent vomiting, anorexia, cardiomyopathy, dermatitis 31 | AOO: childhood, adolescence; MRI: T2W hyperintensities in bilateral globus pallidus 32 |

| Urea cycle disorders | |||

| Argininosuccinic aciduria (ASL)Cerebellar ataxia (intermittent), tremor, myoclonus | Seizures, episodic hypotonia, episodic muscular weakness, developmental delay, intellectual disability, behavioral abnormalities 33 , 34 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy a ; Other features: trichorrhexis nodosa (coarse brittle hair), chronic diarrhea, chronic liver disease 33 , 34 | AOO: childhood, adolescence; Mild cerebellar ataxia may persist 35 ; MRI: generalized atrophy, focal infarcts, T2W basal ganglia and white matter hyperintensities, heterotopia 33 , 34 |

| Other metabolic disorders | |||

|

Lesch–Nyhan disease (HPRT1) Dystonia, chorea, athetosis, ballism |

Axial hypotonia, developmental delay, intellectual disability, impaired language, dysarthria, dysphagia, pyramidal signs, aggressive behavior, self‐mutilating behavior 36 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy, renal stones (orange crystals in baby diapers); Other features: gouty arthritis, subcutaneous tophi | AOO: childhood; Mild variants may be seen in adults 37 ; MRI: normal in routine imaging; reduced basal ganglia and white matter volume in morphometric studies 38 , 39 |

| Wilson disease (ATP7B)Tremor, dystonia, parkinsonism, chorea, myoclonus, cerebellar ataxia | Dysarthria, dysphagia, pyramidal signs, cognitive decline, psychiatric features, seizures 40 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: chronic liver disease, arthropathy, osteomalacia, vitamin D resistant rickets, hemolytic anemia, Kayser‐Fleischer ring, sunflower cataract 41 | AOO: childhood, adolescence, adulthood; MRI: T2W hyperintensities in bilateral basal ganglia, brainstem, thalamus; “face of giant panda” sign in midbrain, “face of miniature panda” sign in pons, bright claustrum sign 40 |

|

Hartnup disease (SLC6A19) Intermittent cerebellar ataxia, chorea, athetosis |

Intermittent diplopia, nystagmus, spastic paraparesis, collapsing falls, headache, psychiatric features, intellectual disability 42 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: photosensitive pellagra‐like skin rashes, diarrhea, short stature | AOO: childhood, adolescence, adulthood; Deletions in the CLTRN gene causes Hartnup disease‐like phenotype 43 ; MRI: delayed myelination, generalized atrophy, thin corpus callosum 44 |

Abbreviations: AOO, age of onset; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; T2W, T2‐weighted.

Predominant renal phenotype is mentioned.

Mechanism underlying renal involvement is not well established.

TABLE 3.

Inherited channelopathies, ciliopathies, and miscellaneous disorders with movement abnormalities and renal involvement

| Disorder (Gene) and Movement Abnormalities | Other Neurological Features | Renal Phenotype* and Other Systemic Features | Additional Features and Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channelopathies | |||

| Epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, and tubulopathy (EAST) syndrome (KCNJ10)Cerebellar ataxia, dystonia | Seizures (generalized, focal), pyramidal signs, sensorineural hearing loss (subclinical or severe), impaired communication, intellectual disability 45 , 46 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy | AOO: childhood; Cerebellar ataxia is nonprogressive but the most disabling feature; MRI: normal or subtle abnormalities (T2W hyperintensities of cerebellar nuclei, cerebellar and brainstem hypoplasia, thin corpus callosum, and thin spinal cord) 47 |

| Ciliopathies and related disorders | |||

|

Joubert syndrome (CEP290, TMEM67, AHI1, several other genes) Cerebellar ataxia, head jerks |

Hypotonia, abnormal respiration, developmental delay, intellectual disability, ocular motor apraxia, impaired smooth pursuit, nystagmus, strabismus, amaurosis, retinopathy, chorioretinal or optic nerve colobomas 48 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: polydactyly, facial dysmorphism, hepatic fibrosis, cardiac malformations, skeletal dysplasia, scoliosis 48 | AOO: childhood; Head jerks compensatory for ocular motor apraxia may be mistaken as tics 49 ; Combinations of clinical features are known by several acronyms and eponymous syndromes; MRI: “molar tooth” sign in axial images due to combination of cerebellar vermis hypodysplasia, thickened and elongated superior cerebellar peduncles, and deep interpeduncular fossa 48 |

|

Oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe (OCRL1) |

Hypotonia, intellectual disability, diminished tendon reflexes 52 | Renal phenotype: tubulopathy; Other features: congenital cataracts, glaucoma, arthropathy, rickets 52 | AOO: childhood; Chorea and athetosis are probably secondary to visual impairment and sensory deprivation 51 ; Dent disease type 2 is an allelic disorder with predominant renal phenotype 52 ; Ciliary dysfunction is one of the many cellular abnormalities 53 ; MRI: delayed myelination, ventriculomegaly; T2W hyperintensities (cystic lesions) in deep and periventricular white matter appear after myelination is complete; tigroid pattern (radially oriented hypointense strips within white matter hyperintensity) may be seen 52 |

| Miscellaneous disorders | |||

|

Nephrocerebellar syndrome (Galloway‐Mowat syndrome) (WDR73) Dystonia, chorea |

Congenital roving nystagmus, seizures, developmental delay, visual impairment 54 | Renal phenotype: glomerulopathy | AOO: childhood; MRI: diffuse cerebral atrophy, thin corpus callosum, cerebellar hypoplasia |

| Congenital nephrotic syndrome of the Finnish type (NPHS1)Dystonia, athetosis | Hypotonia 55 | Renal phenotype: glomerulopathy | AOO: childhood; Mechanism of basal ganglia involvement is not clearly known; MRI: T2W hyperintensities in bilateral globus pallidus 55 |

| Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease (NOTCH2NLC)Cerebellar ataxia, tremor, parkinsonism | Dementia, seizures, pyramidal signs, peripheral neuropathy, autonomic dysfunction 56 | Renal phenotype: glomerulopathy a | AOO: variable; Disease pathogenesis is yet to be determined; Inclusions found in renal tubular cells; mechanism of podocyte damage not known; MRI: T2W confluent hyperintensities involving the cerebral white matter (leukoencephalopathy); DWI hyperintensities in the corticomedullary junction 56 |

Predominant renal phenotype is mentioned; long‐standing glomerulopathy is accompanied by tubular dysfunction and atrophy.

Mechanism underlying renal involvement is not well established.

Abbreviations: AOO, age of onset; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; T2W, T2‐weighted.

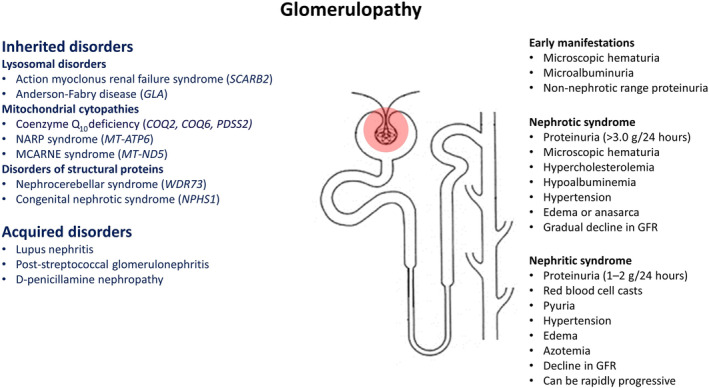

FIG. 1.

Manifestations of glomerulopathy in disorders with movement abnormalities. 52 Abbreviations: GFR, glomerular filtration rate; MCARN, mitochondrial cerebellar ataxia, renal failure, neuropathy, and encephalopathy; NARP, neurogenic muscle weakness, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa.

FIG. 2.

General and site‐specific manifestations of tubulopathy in disorders with movement abnormalities. 53 Abbreviations: CoQ10, coenzyme Q10; EAST, epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, and tubulopathy; KSS, Kearns‐Sayre syndrome; MERRF, myoclonic epilepsy with ragged‐red fibers; MMA, methylmalonic aciduria; mtDNA, mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid; nDNA, nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid; OCRL, oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe; PS, Pearson syndrome; RTA, renal tubular acidosis. aMechanism of renal dysfunction is not clearly known but there is indirect evidence of tubulopathy. bThere is dysfunction of specific neutral amino acid transporter in the proximal convoluted tubule. cRhabdomyolysis can be caused by acquired and inherited movement disorders (see Supplementary Table S1).

TABLE 4.

Movement disorders in renal failure (consequences of azotemia and electrolyte imbalance)

| Etiology or Syndrome | Movement Abnormalities | Other Features and Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Direct consequences of renal failure | ||

| Uremic encephalopathy | Myoclonus, postural and kinetic tremors, ataxia, paratonia, opisthotonus and decorticate posturing 54 , 55 , 56 ; Types of myoclonus: asterixis (negative myoclonus), multifocal jerks, twitch convulsive syndrome (combination of fasciculations, intense asterixis, and multifocal jerks culminating in seizure), and epilepsia partialis continua; myoclonus can be spontaneous, with action or stimulus‐sensitive, distal as well as proximal 55 , 56 , 59 | Variable disturbances in consciousness, perception, and cognition, generalized tonic–clonic seizures, paratonia; Myoclonus usually accompanies lethargy and obtundation; myoclonus can be of subcortical (brainstem reticular‐reflex myoclonus) or cortical origin 39 , 42 ; Opisthotonus and decorticate posturing are seen in advanced cases; Clinical features are more pronounced in rapidly developing uremia |

| Uremic striatopallidal syndrome | Parkinsonism or chorea depending on predominant involvement of the GPi or GPe respectively 60 , 61 ;Parkinsonism: acute to subacute onset of bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability; tremor is typically absent; response to dopaminergic replacement therapy is poor 62 , 63 ; Chorea: acute to subacute onset; may be generalized, focal, asymmetric, or unilateral; sometimes may be followed by parkinsonism 64 , 65 ; can relapse with intercurrent illness or further renal decompensation 66 | Mild encephalopathy, dysarthria, pyramidal signs; Usually occurs in patients on hemodialysis for ESRD as a result of diabetic nephropathy; can occur without preceding dialysis 62 , 67 and in ESRD as a result of another or unknown etiology 63 , 68 ; hypoglycemic events, thiamine deficiency, and metformin can be triggers 61 , 65 , 69 , 70 ; CT: nearly symmetric basal ganglia hypodensity with evidence of edema and mass effect; MRI: basal ganglia hypointensity in T1W images, hyperintensity in T2W and FLAIR images, bright DWI and corresponding ADC (vasogenic edema); dark medial GP on ADC (cytotoxic edema); complete or partial lentiform fork sign in T2W and FLAIR images 71 ; MR angiogram: prominent lenticulostriate arteries in the symptomatic phase 63 ; Prognosis: parkinsonism may resolve partially or completely within weeks to months with intensification of hemodialysis or supportive treatment; radiological resolution occurs earlier; residual cystic changes in the GP and the putamen (bright signal in T2W and ADC) may be a marker for residual neurological impairment 72 , 73 ; chorea usually improves within days to weeks with intensification of hemodialysis; use of dopamine receptor blockers for chorea may cause parkinsonism 66 ; neurological symptoms may persist despite radiological resolution 74 |

| Uremic restless leg syndrome | More severe and less responsive to dopaminergic drugs in comparison to patients without kidney disease 75 , 76 | |

| Consequences of electrolyte imbalance in renal failure | ||

| Hyponatremia | Tremor, myoclonus, ataxia, rigidity 75 | Cramps, encephalopathy, seizures, hyporeflexia |

| Hypernatremia | Tremor, myoclonus, chorea, rigidity 75 | Encephalopathy, seizures, hyperreflexia |

| Hypocalcemia | Tetany, trismus, opisthotonus 75 | Encephalopathy, seizures, Chvostek's sign, Trousseau's sign |

| Hypomagnesemia | Tremor, myoclonus, startle, tetany, chorea 75 | Encephalopathy, seizures, hyperreflexia, Chvostek's sign, Trousseau's sign, downbeat nystagmus 77 |

| Hypophosphatemia | Tremor, ataxia 75 | Weakness, areflexia, perioral paresthesia, encephalopathy, ophthalmoparesis; May mimic Wernicke's encephalopathy |

Abbreviations: ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; CT, computed tomography; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; ESRD, end stage renal disease; FLAIR, fluid attenuated inversion recovery; GP, globus pallidus; GPe, globus pallidus externa; GPi, globus pallidus interna; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; T1W, T1 weighted; T2W, T2 weighted.

TABLE 5.

Movement disorders as consequences of treatment of renal failure

| Etiology or Syndrome | Movement Abnormalities | Other Features and Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Consequences of dialysis in renal failure a | ||

| Dialysis disequilibrium syndrome | Myoclonus, tremor, rarely dystonia 77 , 78 , 79 | Acute onset or worsening of confusion, headache, nausea, cramps, seizures (generalized or focal); Occurs near the end of rapid hemodialysis, as a result of disparity between the blood and the brain pH and urea concentration; In current practice, this condition is rarely seen because of measures that slow down the disparity 77 ; Neuroimaging: diffuse or multifocal cerebral edema |

| Osmotic demyelination syndrome | Parkinsonism, choreo‐athetosis, focal or segmental dystonia, myoclonus, tremor, ataxia, and catatonia (extrapontine myelinolysis); clinical phenotype may evolve from one to another 80 , 81 | Usually occurs as a complication of rapid correction of hyponatremia; rarely seen in ESRD following hemodialysis; Neuroimaging: features of demyelination; Pathological hallmark of osmotic demyelination syndrome is loss of myelin (myelinolysis); the term has been loosely (or perhaps incorrectly) used in the literature in the setting of hemodialysis for cases with dialysis disequilibrium syndrome and uremic striatopallidal syndrome, 81 , 82 although it is known that uremia is protective 80 ; a subset of cases described may be true osmotic demyelination syndrome, whereas others are likely to be reversible vasogenic edema |

| Dialysis dementia | Myoclonus, tremor, ataxia, facial grimacing | Subacute onset cognitive decline, personality change, apraxia, dysarthria, seizures; Attributed to aluminum toxicity; With current use of water purification and non‐aluminum phosphate binders, this condition is not seen 77 , 83 |

| Thiamine deficiency | Ataxia, chorea | Confusion, ophthalmoparesis (components of Wernicke's encephalopathy), psychosis; Patients on chronic hemodialysis are at risk 69 , 83 |

| Consequences of renal transplantation b | ||

| Calcineurin inhibitors | Tremor, ataxia 84 | Peripheral neuropathy; Drugs used as immunosuppressive therapy |

Manganese accumulation in the globus pallidus has been reported in patients on hemodialysis 85 but this has not been investigated further; patients did not have typical clinical features of manganism.

Movement disorders may be presenting features of brain tumors or central nervous system infections, which often complicate patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy following renal transplantation.

Abbreviations: ESRD, end stage renal disease.

Search Strategy

We reviewed English‐written articles and abstracts published in PubMed from January 1964 to February 2020 using the combination of Medical Subject Headings “kidney disease” and “movement disorders,” “parkinsonian disorders,” “chorea,” “athetosis,” “dystonia,” “dyskinesias,” “tremor,” “myoclonus,” “tics,” or “stereotypic movement disorder.” We selected the articles relevant to our review and included additional articles from the references.

Inherited Disorders

Lysosomal Disorders

Action Myoclonus Renal Failure Syndrome

Action myoclonus renal failure syndrome is caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in the SCARB2 gene. 86 When it was first described in 1986 in 4 French‐Canadian individuals from 3 families, the authors recognized that the clinical features resulted from a pathophysiological process involving both the brain and the kidney and were not consequences of renal failure. 87 Since then, at least 40 affected individuals from 29 families have been reported worldwide. The median age of onset of neurological manifestations or renal abnormalities is 19 years (range, 9–52 years). Neurological symptoms can manifest before, with, or after biochemical evidence of renal dysfunction. Typically, patients initially have tremor (likely rhythmic cortical myoclonus; see below) of fingers and hands, which may be present at rest but is markedly worsened with action such as writing. Later, tremor may involve head, trunk, legs, tongue, and voice. Within months or a few years, patients develop action myoclonus of distal extremities. In some patients, gait instability and falls attributed to myoclonic jerks of the legs are the presenting features. Patients may have bulbar myoclonus particularly while speaking. Myoclonus may be variably sensitive to touch, light, or sound and may be worsened with anxiety, fatigue, concentration, fever, and menses. There may be myoclonic status with hyperhidrosis. 88 Photosensitivity may be extreme in some patients causing them to prefer darkness. Patients also have asynchronous jerks involving arms, legs, trunk, and face at rest. Action myoclonus is the most disabling feature of the disorder and is refractory to treatment. In the final stages, it renders the patients bound to wheelchair or bedridden. With disease progression, most patients develop ataxia and dysarthria. Although it is difficult to distinguish ataxia from action myoclonus, other features such as hypotonia, pendular reflexes, nystagmus, abnormal rebound, abnormal neuroimaging in some patients, and pathological findings support cerebellar involvement.

Many patients develop generalized tonic–clonic seizures during the course of the disease. Some of them have drug refractory seizures and convulsive status epilepticus followed by worsening of symptoms and death. Slowed horizontal saccades, sensorineural hearing loss, and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy (mostly subclinical) are other neurological features reported in some patients. Sparing of cognitive function differentiates action myoclonus renal failure syndrome from other progressive myoclonus epilepsies such as neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses and Lafora body disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is usually normal or may show cerebellar or cerebral atrophy in some patients. Electroencephalography may show generalized epileptiform abnormalities with normal background activity initially, similar to idiopathic generalized epilepsies; there is slowing of background activity subsequently. Intermittent photic stimulation can trigger bursts of generalized spike‐wave or polyspike‐wave discharges; these manifest clinically as myoclonic jerks that can evolve to myoclonic seizures. Surface electromyography recordings show quasi‐rhythmic bursts lasting less than 50 milliseconds at 12 to 20 Hz frequency in upper extremities while maintaining posture, clinically resembling postural tremor, in addition to erratic myoclonic jerks at rest. Coherence spectral analysis of electroencephalography–electromyography reveals that tremor in these patients is actually rhythmic myoclonus of cortical origin. 89

Pathologically, there is extraneuronal accumulation of irregularly shaped, refractile, and autofluorescent pigment granules in the cerebral cortex, the globus pallidus, the putamen, and the cerebellar cortex. Based on staining pattern, it is perhaps lipofuscin‐like oxidized lipid or proteolipid. 6 , 87 Mild neuronal loss and gliosis were found in the pallidolusian and the cerebello‐olivary regions in addition to extraneuronal pigment accumulation in the autopsy specimens of 2 atypical Japanese patients who developed prominent dementia. 11

Renal dysfunction can vary from isolated proteinuria to nephrotic syndrome and end‐stage renal disease (ESRD). In two thirds of patients with renal involvement there is relentless progression to ESRD requiring dialysis or renal transplantation by the third decade of life. Renal histopathology shows predominantly glomerular involvement in the form of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and collapsing glomerulopathy. 6 , 86 Isometric vacuolization in distal and collecting tubules and granular material in cortical tubules may also be seen. 90 , 91 Neurological features continue to progress despite management of renal disease (transplantation or otherwise), frequently leading to death by the third or fourth decade.

About one third of patients with SCARB2 mutations have been followed for a median duration of 10 years without demonstrating clinical and biochemical evidence of renal involvement. Thus, before renal dysfunction manifests this disorder mimics other progressive myoclonus epilepsies such as Unverricht‐Lundborg disease, sialidosis, PRICKLE‐1 mutation, and mitochondrial cytopathies, all of which can spare cognitive functions.

The SCARB2 gene encodes lysosomal integral membrane protein type 2 (LIMP‐2), a ubiquitously expressed transmembrane protein in the lysosomes and the late endosomes. 86 A total of 19 mutations (frameshift, splice‐site, nonsense, and missense) have been identified so far, including 2 founder mutations (Q228X in the French‐Canadian population of Quebec and W146SfsX161 in the Scottish population). LIMP‐2 binds β‐glucocerebrosidase in the endoplasmic reticulum and escorts it to the late endosomes and the lysosomes where acidic pH dissociates the complex. Absence of LIMP‐2 leads to a depletion of post‐Golgi forms of β‐glucocerebrosidase. SCARB2 −/− mice manifest peripheral neuropathy, deafness, ataxic gait, hydronephrosis secondary to uretero‐pelvic obstruction, and glomerular abnormalities including mesangial hypercellularity and effacement of foot processes. 86 Interestingly, 1 patient had sustained improvement in myoclonic jerks and speech for almost 2 years by substrate reduction therapy with miglustat 600 mg/day. 90

Anderson‐Fabry Disease (AFD)

AFD is an X‐linked disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the GLA gene causing complete or partial deficiency of the enzyme α‐galactosidase A and progressive accumulation of globotriaosylceramide within lysosomes. 92 It may be an underdiagnosed disorder because the systemic complications are often mild, nonspecific, and occur commonly in the general population. Not only males but also females can be affected with variable severity of symptoms. 14 Cerebrovascular events and renal dysfunction are among the protean manifestations of AFD (see Table 1). Vascular parkinsonism is a rare manifestation of small vessel disease in AFD. 12 A recent study showed that affected individuals have disturbances in gait and hand dexterity. 13 Progressive renal dysfunction, characterized by a mixture of glomerulopathy and tubulopathy, leads to ESRD in the fourth or fifth decade of life. 93 Enzyme replacement therapy may slow the decline in renal function but does not prevent neurological complications. 14

Mitochondrial Cytopathies (MCPs)

MCPs involve the nervous system predominantly, but several other organs can be affected, resulting in wide variability of clinical features. The overall prevalence of MCPs is estimated to be 1:5000. 94 The genetic causes are attributed to pathogenic variants in mitochondrial genes (ie, mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid) or nuclear genes encoding proteins affecting mitochondrial respiratory chain function. The expression of a clinical phenotype is dependent upon several factors such as gene–gene interaction, heteroplasmy, threshold effect (mutation load and reliance of different tissues upon oxidative metabolism), mitochondrial fission and fusion, random segregation, genetic bottleneck, and positive selection. 95 More than 40 clinical syndromes have been reported, but patients frequently have overlapping features. Myoclonus and ataxia are the most frequently encountered movement disorders in MCPs. In addition, parkinsonism, dystonia, chorea, spasticity, tremor, and tics have also been reported. 96 Renal involvement is underreported because it may be subclinical or overshadowed by dysfunction of other organs.

MCPs such as Kearns‐Sayre syndrome; Pearson syndrome; Leigh syndrome; neurogenic muscle weakness, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa syndrome; and myoclonic epilepsy with ragged‐red fibers are known to manifest movement abnormalities in children and young adults (see Table 1). Kearns‐Sayre and Pearson syndromes are multisystem disorders caused by large‐scale deletions or duplications of mitochondrial genome. Leigh syndrome of variable severity is caused by pathogenic variants in several mitochondrial or nuclear genes encoding respiratory chain subunits. Heteroplasmic point mutations in the MT‐ATP6 gene cause neurogenic muscle weakness, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa syndrome. Myoclonic epilepsy with ragged‐red fibers is most frequently caused by point mutations in the MT‐TK gene.

Renal dysfunction can occur in all of these MCPs. The predominant renal phenotype depends on the preferential involvement of the podocytes and the tubular cells. Kearns‐Sayre syndrome, Pearson syndrome, Leigh syndrome, and myoclonic epilepsy with ragged‐red fibers are usually accompanied by renal tubular dysfunction, manifesting as de Toni‐Debré‐Fanconi syndrome, renal tubular acidosis (RTA), Bartter‐like phenotype, isolated hypomagnesemia, or hypocalciuria. 97 , 98 Rarely, proximal tubulopathy and RTA can be presenting features of Kearns‐Sayre syndrome. 16 Histopathological and ultrastructural studies often show abnormalities of proximal tubule epithelia and proliferation of abnormal mitochondria. 98 Glomerular dysfunction in the form of FSGS leading to ESRD was reported in a patient with neurogenic muscle weakness, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa syndrome. Electron microscopic examination of tubular cells and podocytes showed accumulation of swollen and pleomorphic mitochondria with disoriented cristae containing paracrystalline inclusions. 20 Another patient with slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia and other neurological features was reported to develop FSGS leading to ESRD requiring renal transplantation. Electron microscopy did not show abnormal mitochondria but genomic analysis of a renal biopsy specimen revealed heteroplasmic m.13513G>A variant in the MT‐ND5 gene, underlying the importance of having sequencing from kidney. The authors named the phenotype mitochondrial cerebellar ataxia, renal failure, neuropathy, and encephalopathy syndrome. 99

Primary coenzyme‐Q10 (CoQ10) or ubiquinone deficiency is caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in nuclear genes involved in its synthesis and is potentially treatable with CoQ10 supplementation. This is a clinically heterogenous disorder that presents with distinct neurological phenotypes such as cerebellar ataxia, dystonia, encephalomyopathy, and severe infantile multisystem disorder. Childhood‐onset steroid‐resistant nephrotic syndrome may be seen in CoQ10 deficiency from pathogenic variants in the COQ2, COQ6, and PDSS2 genes. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 If not treated, there may be rapid progression to ESRD. Pathologically, there is FSGS or collapsing glomerulopathy. Electron microscopy shows dysmorphic mitochondria in the podocytes. 100 Tubulopathy was reported in a child with encephalopathy, seizures, and dystonia attributed to a pathogenic variant in the COQ9 gene. 26

Organic Acidurias and Urea Cycle Disorders

The neurological spectrum of the rare organic acidurias and urea cycle disorders encompasses a variety of movement disorders. Prominent renal involvement is seen commonly in glutaric aciduria, methylmalonic aciduria, and argininosuccinic aciduria and rarely in propionic aciduria. 101

Glutaric Aciduria Type 1

In glutaric aciduria type 1, deficiency of glutaryl‐CoA dehydrogenase attributed to biallelic pathogenic variants in the GCDH gene results in the impaired breakdown of lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan and the accumulation of neurotoxic metabolites, 3‐hydroxyglutaric acid, glutaric acid, glutaconic acid, and glutylcarnitine. 102 , 103 Affected individuals commonly have progressive macrocephaly at or shortly after birth. Later they develop dystonia with intermittent tonic posturing attributed to irreversible damage of the basal ganglia from encephalopathic crises in the setting of catabolic states or intercurrent illness in infancy or early childhood. Although many patients develop parkinsonism, chorea, and athetosis, dystonia remains the predominant movement disorder. Some children may remain asymptomatic or develop an insidious onset movement disorder or motor delay. 104 Low‐lysine diet, carnitine supplementation, and intensive management of intercurrent illness are recommended to prevent damage to the basal ganglia. 103

About one fourth of affected individuals develop chronic renal failure in the second or third decade of life. 101 In GCDH −/− mice, metabolic crises induced by administration of high‐protein diet cause thinning of brush border membranes and mitochondrial swelling in the renal proximal tubule cells through alteration of transporters and intracellular accumulation of glutaric acid and 3‐hydroxiglutaric acid. 105 Thus, it is speculated that chronic exposure to these excreted toxins impair mitochondrial function of the renal proximal tubules and make them susceptible to catabolic states. 106

Methylmalonic Aciduria (MMA)

Defective breakdown of methylmalonyl‐coenzyme A causes MMA and secondarily hyperammonemia and ketoacidosis. Isolated MMA results from biallelic pathogenic variants in the gene encoding the apoenzyme methylmalonyl‐CoA mutase (MMUT) or in the genes involved in the synthesis of its cofactor adenosylcobalamin (MMAA, MMAB, and MMADHC). Other disorders of cobalamin metabolism manifest as combined MMA and homocystinuria. 107 Affected individuals present with metabolic crisis characterized by encephalopathy, hypotonia, vomiting, and sepsis‐like picture in the neonatal period, childhood, or adolescence. Those who recover variably develop dystonia, chorea, myoclonus, tremor, ataxia, pyramidal signs, intellectual disability, and dysfunction of other organs. 31 Intercurrent illness or catabolic states can cause metabolic strokes involving the globus pallidus bilaterally.

About one third or more of patients with MMA develop chronic renal failure by the first or second decade, necessitating dialysis or renal transplantation in some. 101 , 108 Renal histopathology shows tubulointerstitial fibrosis and enlarged mitochondria in the proximal tubular cells. 109 Mitochondrial dysfunction attributed to the accumulation of toxic metabolites is the proposed mechanism for neuronal and renal injury. 110

Management of MMA involves intensive treatment of metabolic crises, dietary changes, and carnitine supplementation. Liver transplantation or combined liver and renal transplantation may provide metabolic stability but not does prevent metabolic strokes. Patients with adenosylcobalamin synthesis defects may respond to treatment with vitamin B12. 31 , 111

Argininosuccinic Aciduria

Argininosuccinic aciduria is caused by deficiency of the urea cycle enzyme argininosuccinate lyase from biallelic pathogenic variants in the ASL gene. 112 Similar to other urea cycle disorders, affected neonates frequently have a severe presentation as a result of hyperammonemia characterized by lethargy, reduced consciousness, seizures, vomiting, and respiratory alkalosis. In those who survive and in late‐onset forms, intercurrent illness or catabolic state can precipitate hyperammonemia lasting several days. During these episodes, patients may have signs of cerebellar ataxia. 113 Mild cerebellar ataxia may persist without episodic hyperammonemia. In addition, patients may have tremor, myoclonic and other types of seizures, episodic hypotonia and muscular weakness, and developmental delay. Argininosuccinic aciduria is unique among the urea cycle disorders because of the higher incidence of cognitive and behavioral abnormalities. Management strategies include treatment of hyperammonemia, dietary changes, arginine supplementation, nitrogen scavenging therapy, and liver transplantation. 112

Patients may develop chronic renal failure by the second decade. 101 Ultrasound shows nephromegaly and poor corticomedullary differentiation. Patients often have hypokalemia perhaps as a result of renal potassium wasting. Hyperammonemia, deficiency of arginine and downstream metabolites such as nitric oxide, and toxicity of argininosuccinate are thought to play a role in the pathogenesis, but the mechanism underlying renal involvement is not well established. 33

Other Metabolic Disorders

Lesch–Nyhan Disease

Lesch–Nyhan disease is an X‐linked recessive disorder caused by deficiency of the purine salvage enzyme hypoxanthine‐guanine phosphoribosyltransferase from pathogenic variants in the HPRT1 gene. 114 , 115 Affected infants have axial hypotonia and developmental delay. Subsequently they develop striking involuntary movements in the form of dystonic posturing of limbs and episodes of torticollis, retrocollis, or opisthotonus. There may be superimposed athetotic, choreic, or ballistic movements. Intellectual disability, impaired language, dysarthria, dysphagia, and pyramidal signs are other neurological features. Typically, they have self‐directed aggressive and mutilating behavior such as biting of the lips and the fingers resulting in partial amputation. 36 There are attenuated variants of Lesch–Nyhan disease with mild motor abnormalities, absent self‐destructive behavior, and preserved cognitive function. The neurological features are attributed to biochemical abnormalities in the brain, and there are no characteristic pathological findings. Cerebellar abnormalities have been found in some autopsy studies. 116

Hyperuricemia results in the formation of renal stones manifesting as hematuria, renal colic, and obstructive uropathy in the setting of dehydration. There is diminished concentrating ability of the kidneys attributed to impaired tubular function. Later, there may be glomerular involvement and renal failure. 117 Control of hyperuricemia and symptomatic treatment of movement disorders are important management strategies.

Wilson's Disease (WD)

The fundamental abnormality in WD is impaired biliary excretion of copper attributed to biallelic loss‐of‐function mutations in the ATP7B gene, resulting in the accumulation of copper in different organs. Patients who manifest neurological features may have a combination of movement abnormalities such as tremor, dystonia, parkinsonism, chorea, myoclonus, and ataxia. In addition, there may be dysarthria, cognitive decline, and psychiatric features. The usual age of presentation is the second or third decade. 40 Accumulation or excretion of copper by the kidney usually causes subtle impairment in function of the renal tubules. Proteinuria, glucosuria, phosphaturia, uricosuria, aminoaciduria, and microscopic hematuria may be detected as biochemical abnormalities. Histopathological examination usually does not show tubular pathology, albeit calcium deposits can be found in the tubules. In some patients tubulopathy manifests as proximal or distal RTA, and partial or complete de Toni‐Debré‐Fanconi syndrome. 41 Hypercalciuria secondary to distal RTA or as a result of calcium mobilization from bones to neutralize systemic acidosis may result in nephrocalcinosis. 118 , 119 Vitamin D resistant rickets can be the presenting feature of WD secondary to RTA and is commonly reported from the Indian subcontinent. 120 In addition to awareness of the renal complications of WD, routine monitoring of renal function is important in patients treated with D‐penicillamine as it may result in nephrotoxicity in about 7% to 11% of them, heralded by proteinuria after about 8 months of therapy. 41 Rarely, D‐penicillamine can trigger immune‐mediated glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome. 121

Hartnup Disease

This disorder, named after the Hartnup family of London, is characterized by impaired renal and intestinal absorption of neutral amino acids, which can lead to deficiency of niacin and serotonin and manifest as neurological, psychiatric, and dermatological abnormalities. 122 , 123 , 124 Most of the affected individuals have a benign course or may remain asymptomatic because intact absorption of peptides compensates for lack of amino acid transport. In symptomatic patients, clinical features include short stature, intermittent photosensitive pellagra‐like skin rashes, and diarrhea. Intermittent cerebellar ataxia is the most common neurological manifestation. Incoordination, intention tremor, nystagmus, and diplopia may occur in bouts lasting several days, often precipitated by fever, infection, intercurrent illness, or inadequate diet. Some patients may have intermittent chorea and athetosis, spastic paraparesis, collapsing falls, seizure, headache, psychiatric symptoms and rarely, intellectual disability. Symptoms usually occur in children but presentation in adults has been reported.

Hartnup disease is caused by biallelic loss‐of‐function variants in the SLC6A19 gene that encodes the neutral amino acid transporter B0AT1 found in the brush border of kidney and intestinal epithelial cells. 125 , 126 More than 20 pathogenic variants (missense, nonsense, splice‐site, deletions) have been identified. B0AT1 requires heterodimerization with collectrin for surface expression and stability in the kidney. Deletions in the CLTRN gene (on Xp22.2) encoding collectrin were recently associated with neuropsychiatric features, motor tics, and neutral aminoaciduria (phenotype resembling Hartnup disease). However, the pathogenesis of these features is not clear because plasma amino acid levels were normal in the affected patients. 43

Channelopathies

Epilepsy, Ataxia, Sensorineural Deafness, and Tubulopathy (EAST) Syndrome

In 2009, 2 groups independently identified a distinct autosomal recessive disorder attributed to homozygous or compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in the KCNJ10 gene using the acronyms EAST (epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, and tubulopathy) and SeSAME (seizures, sensorineural deafness, ataxia, mental retardation, and electrolyte imbalance) to describe the phenotype. 45 , 46 More than 30 patients with 16 different mutations have been reported worldwide. 127 The KCNJ10 gene encodes Kir4.1, an inwardly rectifying potassium channel located in the glial cells of the brain, intermediate cells of the stria vascularis of the inner ear, renal epithelial cells, and retina. Kir4.1 is involved in potassium spatial buffering, which is necessary to maintain the resting membrane potential of neurons. Its dysfunction can cause accumulation of potassium in the extracellular space, leading to neuronal depolarization, hyperexcitability, and reduced seizure threshold. 46

The disorder presents with infantile onset generalized tonic–clonic seizures that are easily controlled by anticonvulsants. About half of the patients subsequently develop focal seizures that may be drug resistant. There is a delay in the development of speech and motor milestones. Ataxia, although nonprogressive, is the most debilitating feature of this disorder. Ataxic gait is evident when the children learn to walk. Cerebellar signs such as intention tremor, dysdiadochokinesia, dysmetria, titubation, truncal ataxia, and scanning speech are usually present. Pyramidal signs and dystonic posturing of limbs and face may develop in older patients. Intellectual disability is difficult to assess because of impaired communication and ataxia in severely affected patients. MRI is often reported as normal but careful analysis may show subtle abnormalities in the brain and the spinal cord, such as T2 and fluid attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensity of cerebellar nuclei, cerebellar and brainstem hypoplasia, thin corpus callosum, and thin spinal cord. 47 , 128 Hearing impairment can vary from mild (or subclinical) to severe.

The renal manifestations are similar to Gitelman syndrome, with hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia, hypocalciuria, activation of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone axis, and urinary loss of sodium, potassium, chloride, and magnesium resulting from defective transport in the distal convoluted tubule. Some patients may have salt craving, enuresis, polyuria, and polydipsia. Renal ultrasound does not show any abnormality. 128 Electron microscopic examination of a renal biopsy has shown decreased basolateral infolding and reduced number of mitochondria in the distal convoluted tubule. 129

Management is focused on controlling seizures, salt supplementation, and hearing aids. Use of potassium sparing diuretics to correct serum potassium levels may place the patients at risk of hypovolemia.

Ciliopathies and Related Disorders

Ciliopathies are disorders caused by mutations in genes with products that localize to the cilium–centrosome complex. 130 Cilia are organelles present on the apical surface of almost every cell type and are involved in a variety of cellular functions such as planar cell polarity, cell‐cycle regulation and transduction of extracellular signals. They integrate multiple signaling pathways of critical importance for development and organ differentiation. There is broad genotype–phenotype overlap between ciliopathies that include Joubert syndrome and nephronophthisis (see next sections) among several disorders. 131

Joubert Syndrome (JS)

JS is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of congenital ataxias with characteristic midbrain–hindbrain malformation comprising hypoplasia and dysplasia of the cerebellar vermis, thickening and elongation of the superior cerebellar peduncles, and deep interpeduncular fossa, giving the radiological appearance of a molar tooth in axial images of the brain. There may be additional brain malformations. 132 There is absence of decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncles and the pyramidal tracts. 133 Molecular diagnosis can be established in about two thirds of the patients by identification of pathogenic variants in more than 30 genes, most with autosomal recessive inheritance. 134 The prevalence rate of JS in the age group of 0 to 19 years was found to be 1.7 per 100,000 in a recent population‐based study from Italy. 135 The clinical features were first described in 4 French‐Canadian siblings in 1969. 136 Patients variably have infantile onset hypotonia, abnormal respiratory pattern (episodes of apnea alternating with tachypnea), ocular motor apraxia, impaired smooth pursuit, nystagmus, strabismus, delayed developmental milestones, intellectual disability, polydactyly, and facial dysmorphisms. About half of the affected children learn to walk independently but have ataxic gait. Some patients may present with head jerks as a compensatory phenomenon for ocular motor apraxia.

The natural history of JS may be affected by involvement of the kidney and other organs at different ages (see Table 3). In a prospective study, about 30% of patients were found to have renal involvement in the form of nephronophthisis, mixed nephronophthisis and polycystic kidney disease, unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney, or indeterminate cystic kidney disease. Renal involvement was commonly associated with mutations in the CEP290, TMEM67, and AHI1 genes. Of the patients with renal involvement, 24% had hypertension before decrease in renal function and 45% developed ESRD between 6 and 24 years of age. 137 Pathologically, nephronophthisis is characterized by thickening and disintegration of the tubular basement membrane, atrophy of renal tubular structure, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. There may be infantile, juvenile, or adolescent onset of symptoms such as polyuria, enuresis, polydipsia, anemia, and growth retardation. There is progression to ESRD in the first 3 decades, necessitating dialysis or renal transplantation. Ultrasound may show small or normal‐sized kidneys, small cysts, loss of corticomedullary differentiation, and increased echogenicity. 131 Timely diagnosis of nephronophthisis is essential to initiate supportive treatment of chronic renal failure and to ensure appropriate fluid intake. Such measures can prevent the development of complications, such as renal osteodystrophy and poor growth. 48

von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) Disease

Ataxia can be a manifestation of cerebellar hemangioblastoma in VHL disease caused by heterozygous germline inactivation of the VHL tumor‐suppressor gene. Cerebrovascular complications of VHL disease resulting from polycythemia or hypertension from pheochromocytoma rarely may present with secondary movement disorders. Renal cysts and renal cell carcinoma are components of the many visceral features of this disease. 130 , 138

Oculocerebrorenal Syndrome of Lowe

Oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe is a rare X‐linked multisystemic disorder characterized by the triad of congenital cataracts, intellectual disability, and proximal renal tubular dysfunction attributed to pathogenic variants in the OCRL1 gene that encodes enzyme phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate localized to the Golgi apparatus. Loss of OCRL1 function results in several cellular defects including impaired formation of cilia and endocytic trafficking. 48 Affected individuals are symptomatic from birth with hypotonia and diminished tendon reflexes. 52 Children may have behavioral abnormalities including irritability, stubbornness, obsessions, and stereotypy. Choreoathetoid movements have been reported, but they are considered secondary to visual impairment and sensory deprivation.

Miscellaneous Inherited Disorders

Nephrocerebellar Syndrome

Galloway‐Mowat syndrome, first described in 1968, is the combination of infantile‐onset steroid‐resistant nephrotic syndrome and central nervous system abnormalities (neuronal migration defects, cerebellar atrophy, hypomyelination) clinically manifesting as microcephaly, psychomotor delay, intractable epilepsy, and mild dysmorphic features. 139 , 140 It is caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in the WDR73 gene encoding a protein that is expressed in the embryonic brain and kidneys and associates with the mitotic microtubules during cell division. It is thought to participate in cellular functions such as cell division, signal transduction, vesicle trafficking, cytoskeletal dynamics, DNA excision repair, nuclear envelope transport, and autophagy. 54 , 141 Recently the spectrum of Galloway‐Mowat syndrome was expanded by description of a nephrocerebellar syndrome characterized by progressive microcephaly, visual impairment, congenital roving nystagmus, stagnant psychomotor development, multifocal seizures, hypotonia, axial dystonia, chorea, and steroid‐resistant nephrotic syndrome or renal failure in 30 children of Amish populations. 54 Neuroimaging showed diffuse cerebral atrophy, thinning of the corpus callosum, and hypoplasia and progressive atrophy of the cerebellum. About 50% of the patients died in the first 3 decades of life from renal failure. Brain pathology included profound loss of cerebellar granule cells, cerebellar gliosis, and selective loss of striatal cholinergic interneurons. Marked effacement and microvillus transformation of podocyte foot processes, and FSGS were found in renal tissues.

Congenital Nephrotic Syndrome of the Finnish Type

This disorder is caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in the NPHS1 gene that encodes nephrin, a cell adhesion molecule expressed in the slit diaphragm of glomerular podocytes. About 9% of affected children may develop dystonia, athetosis, and hypotonia during the first year of life. MRI of the brain shows hyperintensity of the globus pallidus in T2‐weighted and fluid attenuated inversion recovery images. Secondary mitochondrial dysfunction and chronic bilirubin encephalopathy (with hypoalbuminemia as a risk factor) have been speculated as pathogenic mechanisms, yet the association remains obscure. 55

Neuronal Intranuclear Inclusion Disease

It was recently discovered that sporadic as well as familial neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease is caused by heterogenous GGC repeat expansions in the 5′ untranslated region of the human‐specific NOTCH2NLC gene that is highly expressed in various radial glia populations and may have a role in neurogenesis through Notch signaling. 142 The expansions neither change the gene expression nor cause hypermethylation (gene silencing) but may result in abnormal antisense transcripts. 142 , 143 , 144 Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disorder manifesting with broad clinical manifestations such as dementia, cerebellar ataxia, extrapyramidal symptoms, seizures, pyramidal signs, neuropathy, and autonomic dysfunction. 56 There is scarce evidence of organ dysfunction outside the nervous system despite the widespread presence of characteristic anti‐ubiquitin and anti‐p62 reactive eosinophilic hyaline inclusions in various tissues including renal tubular cells. 56 Two patients were reported with glomerulonephritis before the onset of neurological symptoms, 145 , 146 and few other patients had biochemical evidence of renal dysfunction. 56 It is not clear if renal involvement is part of the disease process.

Acquired Disorders

Several vascular, immune‐mediated, neoplastic, and toxic disorders that involve both the kidneys and the nervous system are associated with movement disorders. Immunological and vasculitic processes in autoimmune disorders of the kidneys may affect the basal ganglia. Chorea and ballism (hemi or bilateral) are known complications of systemic lupus erythematosus that may be associated with nephritis and antiphospholipid antibodies. 147 Parkinsonism can also be a rare manifestation of central nervous system vasculitis associated with lupus nephritis. 148 These are potentially reversible with appropriate immunotherapy. Sydenham's chorea is occasionally associated with acute post–streptococcal glomerulonephritis. 149 Vasculitic infarcts in the basal ganglia causing contralateral choreoathetoid movements have been reported in some patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome. 150 Chorea, ballism, and opsoclonus‐myoclonus may occur as paraneoplastic syndromes antedating the detection of renal cell carcinoma. 151 , 152 Mercury toxicity can present with tremor, cerebellar ataxia, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and renal tubular dysfunction. Organ susceptibility depends on the form of exposure. 153 Intoxication with ethylene glycol and methanol rarely results in parkinsonism through necrosis of the basal ganglia (predominantly putamen) from metabolic acidosis and metabolites such as oxalic acid and formic acid, respectively. 154 Necrosis of the renal proximal tubular cells can occur from internalized calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals in ethylene glycol toxicity and secondarily from hypotension, myoglobinuria, and hemoglobinuria in methanol toxicity. 155 , 156 A variety of drugs may result in movement disorders combined with renal dysfunction. For example, lithium toxicity manifests with action tremor, cerebellar ataxia, and renal involvement in the form of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and reduction in glomerular filtration rate. 157 Several other drugs (acyclovir, cephalosporin, etc.) may cause tremor, myoclonus, chorea, and ataxia in the setting of renal dysfunction. 158 , 159

Conclusions

There are several inherited and acquired disorders in which involvement of the nervous system and the kidneys gives rise to movement disorders and renal dysfunction, typically independent of each other (with some exceptions such as Hartnup disease and rhabdomyolysis related acute kidney injury). It is important to recognize these disorders because their management is challenging and needs targeted approach. Although treatment of renal dysfunction may have a positive impact on morbidity and mortality, it generally does not improve neurological outcome. In contrast, a variety of movement disorders occur more commonly as direct or indirect consequences of renal dysfunction and its management (Tables 4 and 5) and are potentially reversible with appropriate treatment.

We acknowledge that there are some limitations of this review. Not all case reports and series provide detailed description of movement disorder phenomenology and severity. It is difficult to draw conclusions from case reports mentioning renal involvement in some disorders as this could be a chance occurrence. For instance, paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia and cerebellar ataxia have been reported in patients with cystinuria, a relatively common hereditary disorder characterized by impaired tubular transport of cysteine and dibasic amino acids, but the pathophysiology of neurological involvement has not been delineated clearly. 160 , 161 Cerebellar ataxia and other movement disorders may be part of the complex phenotype of several hereditary disorders that involve the nervous system and other visceral organs including, rarely, the kidneys, such as congenital disorders of glycosylation and peroxisomal disorders. 162 , 163 , 164 The discussion of all of these disorders is beyond the scope of this review.

Author Roles

(1) Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

S.S.B.: 1B, 1C, 3A

A.E.L.: 1A, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: Approval from institutional review board or ethics committee was not required for this work. Informed patient consent was not necessary for this work. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflict of Interest: We did not receive specific funding for this work. We declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Financial Disclosures for Previous 12 Months: We declare that there are no additional disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Table S1. Renal dysfunction due to movement disorders or their treatment.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Tyler HR. Neurologic disorders in renal failure. Am J Med 1968;44(5):734–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tyler HR. Neurologic disorders seen in the uremic patient. Arch Intern Med 1970;126(5):781–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raskin NH, Fishman RA. Neurologic disorders in renal failure (first of two parts). N Engl J Med 1976;294(3):143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Espay AJ. Neurologic complications of electrolyte disturbances and acid‐base balance. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;119:365–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bansal VK, Bansal S. Nervous system disorders in dialysis patients. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;119:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Badhwar A, Berkovic SF, Dowling JP, et al. Action myoclonus‐renal failure syndrome: characterization of a unique cerebro‐renal disorder. Brain 2004;127(Pt 10):2173–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dibbens LM, Karakis I, Bayly MA, Costello DJ, Cole AJ, Berkovic SF. Mutation of SCARB2 in a patient with progressive myoclonus epilepsy and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Arch Neurol 2011;68(6):812–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perandones C, Micheli FE, Pellene LA, Bayly MA, Berkovic SF, Dibbens LM. A case of severe hearing loss in action myoclonus renal failure syndrome resulting from mutation in SCARB2. Mov Disord 2012;27(9):1200–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guerrero‐Lopez R, Garcia‐Ruiz PJ, Giraldez BG, et al. A new SCARB2 mutation in a patient with progressive myoclonus ataxia without renal failure. Mov Disord 2012;27(14):1826–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hopfner F, Schormair B, Knauf F, et al. Novel SCARB2 mutation in action myoclonus‐renal failure syndrome and evaluation of SCARB2 mutations in isolated AMRF features. BMC Neurol 2011;11:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fu YJ, Aida I, Tada M, et al. Progressive myoclonus epilepsy: extraneuronal brown pigment deposition and system neurodegeneration in the brains of Japanese patients with novel SCARB2 mutations. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014;40(5):551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buechner S, De Cristofaro MT, Ramat S, Borsini W. Parkinsonism and Anderson Fabry's disease: a case report. Mov Disord 2006;21(1):103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lohle M, Hughes D, Milligan A, et al. Clinical prodromes of neurodegeneration in Anderson‐Fabry disease. Neurology 2015;84(14):1454–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schiffmann R, Ries M. Fabry disease: a disorder of childhood onset. Pediatr Neurol 2016;64:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Finsterer J. Mitochondrial ataxias. Can J Neurol Sci 2009;36(5):543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eviatar L, Shanske S, Gauthier B, et al. Kearns‐Sayre syndrome presenting as renal tubular acidosis. Neurology 1990;40(11):1761–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farruggia P, Di Cataldo A, Pinto RM, et al. Pearson syndrome: a retrospective cohort study from the Marrow Failure Study Group of A.I.E.O.P. (Associazione Italiana Emato‐Oncologia Pediatrica). JIMD Rep 2016;26:37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Finsterer J. Leigh and Leigh‐like syndrome in children and adults. Pediatr Neurol 2008;39(4):223–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lamperti C, Zeviani M. Myoclonus epilepsy in mitochondrial disorders. Epileptic Disord 2016;18(s2):94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lemoine S, Panaye M, Rabeyrin M, et al. Renal involvement in neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa (NARP) syndrome: a case report. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71(5):754–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ng PS, Pinto MV, Neff JL, et al. Mitochondrial cerebellar ataxia, renal failure, neuropathy, and encephalopathy (MCARNE). Neurol Genet. 2019;5(2):e314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rotig A, Appelkvist EL, Geromel V, et al. Quinone‐responsive multiple respiratory‐chain dysfunction due to widespread coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Lancet 2000;356(9227):391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quinzii C, Naini A, Salviati L, et al. A mutation in para‐hydroxybenzoate‐polyprenyl transferase (COQ2) causes primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Am J Hum Genet 2006;78(2):345–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heeringa SF, Chernin G, Chaki M, et al. COQ6 mutations in human patients produce nephrotic syndrome with sensorineural deafness. J Clin Invest 2011;121(5):2013–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lopez LC, Schuelke M, Quinzii CM, et al. Leigh syndrome with nephropathy and CoQ10 deficiency due to decaprenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2 (PDSS2) mutations. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79(6):1125–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duncan AJ, Bitner‐Glindzicz M, Meunier B, et al. A nonsense mutation in COQ9 causes autosomal‐recessive neonatal‐onset primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency: a potentially treatable form of mitochondrial disease. Am J Hum Genet 2009;84(5):558–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ebrahimi‐Fakhari D, Van Karnebeek C, Munchau A. Movement disorders in treatable inborn errors of metabolism. Mov Disord 2019;34(5):598–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohammad SA, Abdelkhalek HS, Ahmed KA, Zaki OK. Glutaric aciduria type 1: neuroimaging features with clinical correlation. Pediatr Radiol 2015;45(11):1696–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nicolaides P, Leonard J, Surtees R. Neurological outcome of methylmalonic acidaemia. Arch Dis Child 1998;78(6):508–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tan AH, Mah JSY, Thong MK, Lim SY. Methylmalonic aciduria: a treatable disorder of which adult neurologists need to be aware. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2016;3(1):104–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baumgartner MR, Horster F, Dionisi‐Vici C, et al. Proposed guidelines for the diagnosis and management of methylmalonic and propionic acidemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baker EH, Sloan JL, Hauser NS, et al. MRI characteristics of globus pallidus infarcts in isolated methylmalonic acidemia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36(1):194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baruteau J, Diez‐Fernandez C, Lerner S, et al. Argininosuccinic aciduria: recent pathophysiological insights and therapeutic prospects. J Inherit Metab Dis 2019;42(6):1147–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baruteau J, Jameson E, Morris AA, et al. Expanding the phenotype in argininosuccinic aciduria: need for new therapies. J Inherit Metab Dis 2017;40(3): 357–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schutgens RB, Beemer FA, Tegelaers WH, de Groot WP. Mild variant of argininosuccinic aciduria. J Inherit Metab Dis 1980;2(1):13–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jinnah HA, Visser JE, Harris JC, et al.Delineation of the motor disorder of Lesch‐Nyhan disease. Brain 2006;129(Pt 5):1201–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jinnah HA, Ceballos‐Picot I, Torres RJ, et al. Attenuated variants of Lesch‐Nyhan disease. Brain 2010;133(Pt 3):671–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schretlen DJ, Varvaris M, Ho TE, et al. Regional brain volume abnormalities in Lesch‐Nyhan disease and its variants: a cross‐sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12(12):1151–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schretlen DJ, Varvaris M, Vannorsdall TD, Gordon B, Harris JC, Jinnah HA. Brain white matter volume abnormalities in Lesch‐Nyhan disease and its variants. Neurology 2015;84(2):190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pfeiffer RF. Wilson disease. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(4):1246–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dziezyc K, Litwin T, Czlonkowska A. Other organ involvement and clinical aspects of Wilson disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2017;142:157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Donaldson I, Marsden CD, Schneider SA, Bhatia KP. Intermittent ataxias In: Marsden's Book of Movement Disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012;1419–1427. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pillai NR, Yubero D, Shayota BJ, et al. Loss of CLTRN function produces a neuropsychiatric disorder and a biochemical phenotype that mimics Hartnup disease. Am J Med Genet A 2019;179(12):2459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Erly W, Castillo M, Foosaner D, Bonmati C. Hartnup disease: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1991;12(5):1026–1027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bockenhauer D, Feather S, Stanescu HC, et al. Epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy, and KCNJ10 mutations. N Engl J Med 2009;360(19):1960–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Scholl UI, Choi M, Liu T, et al. Seizures, sensorineural deafness, ataxia, mental retardation, and electrolyte imbalance (SeSAME syndrome) caused by mutations in KCNJ10. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106(14):5842–5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cross JH, Arora R, Heckemann RA, et al. Neurological features of epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013;55(9):846–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Romani M, Micalizzi A, Valente EM. Joubert syndrome: congenital cerebellar ataxia with the molar tooth. Lancet Neurol 2013;12(9):894–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Borngraber F, Peng Y, Ostendorf F, Kuhn AA, Ganos C. Teaching video NeuroImages: characteristic head jerks in congenital oculomotor apraxia due to Joubert syndrome. Neurology 2019;93(11):e1125–e1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kenworthy L, Charnas L. Evidence for a discrete behavioral phenotype in the oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe. Am J Med Genet 1995;59(3):283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Donaldson I, Marsden CD, Schneider SA, Bhatia KP. Other inherited secondary (symptomatic) dystonias In: Marsden's Book of Movement Disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012:1201–1232. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bokenkamp A, Ludwig M. The oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe: an update. Pediatr Nephrol 2016;31(2212):2201–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mehta ZB, Pietka G, Lowe M. The cellular and physiological functions of the Lowe syndrome protein OCRL1. Traffic 2014;15(5):471–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jinks RN, Puffenberger EG, Baple E, et al. Recessive nephrocerebellar syndrome on the Galloway‐Mowat syndrome spectrum is caused by homozygous protein‐truncating mutations of WDR73. Brain 2015;138(Pt 8):2173–2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Laakkonen H, Lonnqvist T, Uusimaa J, et al. Muscular dystonia and athetosis in six patients with congenital nephrotic syndrome of the Finnish type (NPHS1). Pediatr Nephrol 2006;21(2):182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sone J, Mori K, Inagaki T, Katsumata R, et al. Clinicopathological features of adult‐onset neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Brain 2016;139(Pt 12):3170–3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lewis JB, Neilson EG. Glomerular diseases In: Kasper DL, Fauci SA, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. New York: The McGraw‐Hill Companies, Inc.; 2015:1831–1850. [Google Scholar]

- 58. George AL Jr, Neilson EG. Cellular and molecular biology of the kidney In: Kasper DL, Fauci SA, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. New York: The McGraw‐Hill Companies, Inc.; 2015:332e1–e11. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Barrett KM. Neurologic manifestations of acute and chronic renal disease. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2011;17(1):45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Park JH, Kim HJ, Kim SM. Acute chorea with bilateral basal ganglia lesions in diabetic uremia. Can J Neurol Sci 2007;34(2):248–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lizarraga KJ, Adams D, Post MJD, Skyler J, Singer C. Neurovascular uncoupling after rapid glycemic control as a trigger of the diabetic‐uremic striatopallidal syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;39:89–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cupidi C, Piccoli F, La Bella V. Acute reversible parkinsonism in a diabetic‐uremic patient. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2006;108(6):601–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee PH, Shin DH, Kim JW, Song YS, Kim HS. Parkinsonism with basal ganglia lesions in a patient with uremia: evidence of vasogenic edema. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2006;12(2):93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim YJ, Kim SJ, Kim J, et al. Chorea due to diabetic hyperglycemia and uremia: distinct clinical and imaging features. Mov Disord 2015;30(3):419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jurynczyk M, Rozniecki J, Zaleski K, Selmaj K. Hypoglycemia as a trigger for the syndrome of acute bilateral basal ganglia lesions in uremia. J Neurol Sci 2010;297(1–2):74–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dicuonzo F, Di Fede R, Salvati A, et al. Acute extrapyramidal disorder with bilateral reversible basal ganglia lesions in a diabetic uremic patient: diffusion‐weighted imaging and spectroscopy findings. J Neurol Sci 2010;293(1–2):119–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yalcin G, Ozgen B, Varli K, Topcuoglu MA. Diabetic uremic syndrome. J Neurol 2008;255(9):1415–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Okada J, Yoshikawa K, Matsuo H, Kanno K, Oouchi M. Reversible MRI and CT findings in uremic encephalopathy. Neuroradiology 1991;33(6):524–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hung SC, Hung SH, Tarng DC, Yang WC, Huang TP. Chorea induced by thiamine deficiency in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;37(2):427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. McGarvey C, Franconi C, Prentice D, Bynevelt M. Metformin‐induced encephalopathy: the role of thiamine. Intern Med J 2018;48(2):194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kumar G, Goyal MK. Lentiform fork sign: a unique MRI picture. Is metabolic acidosis responsible? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2010;112(9):805–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kim TK, Seo SI, Kim JH, Lee NJ, Seol HY. Diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the syndrome of acute bilateral basal ganglia lesions in diabetic uremia. Mov Disord 2006;21(8):1267–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ishii K, Ishii K, Shioya A, Nemoto K, Tamaoka A. Decreased dopamine transporter and receptor ligand binding in Parkinsonism with diabetic uremic syndrome. Ann Nucl Med 2016;30(4):320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hamed S, Mohamed K, Abd Elhameed S, et al. Movement disorders due to selective basal ganglia lesions with uremia. Can J Neurol Sci 2020;47(3):350–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]