ABSTRACT

Background: As displacement and forced migration continue to exhibit global growth trends, new and surviving generations of children are being born and spending their formative years in host countries. Refugee children who have not been exposed to traumatic events may still be at risk for adverse developmental and mental health outcomes via intergenerational trauma transmission.

Objective: To identify and synthesize potential mechanisms of intergenerational trauma transmission in forcibly displaced families where parents have experienced direct war-related trauma exposure, but children have no history of direct trauma exposure.

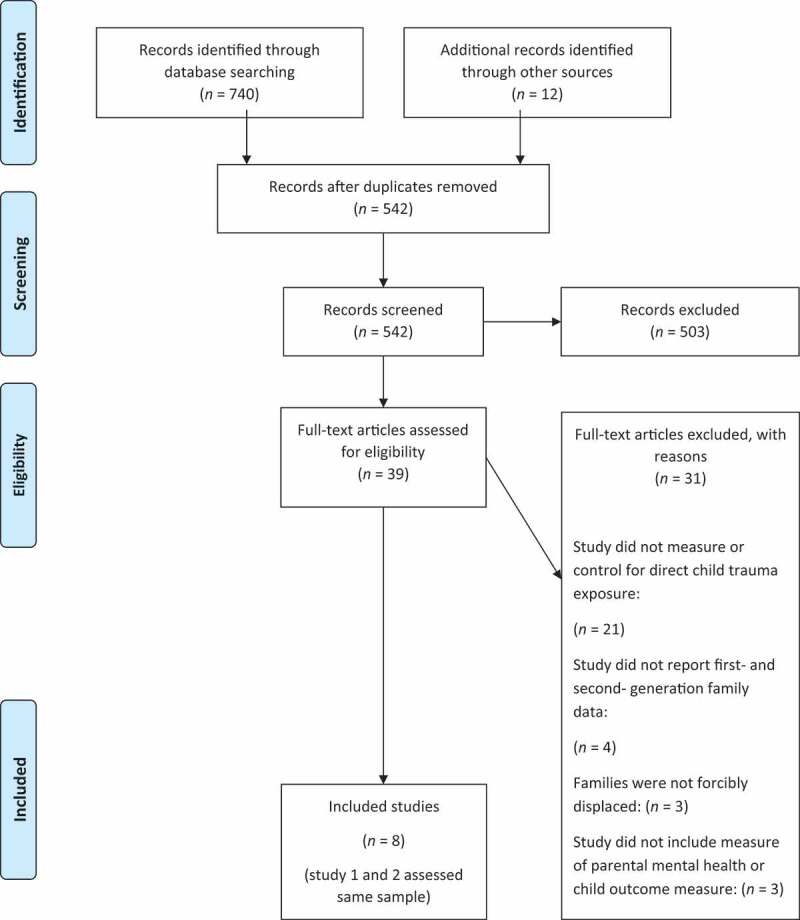

Methods: PRISMA systematic review guidelines were adhered to. Searches were conducted across seven major databases and included quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods literature from 1945 to 2019. The search resulted in 752 citations and 8 studies (n = 1,684) met review inclusion criteria.

Results: Findings suggest that parental trauma exposure and trauma sequelae indirectly affect child well-being via potential mechanisms of insecure attachment; maladaptive parenting styles; diminished parental emotional availability; decreased family functioning; accumulation of family stressors; dysfunctional intra-family communication styles and severity of parental symptomology.

Conclusion: Further research is needed to assess independent intergenerational effects and mechanisms of trauma transmission in this population.

KEYWORDS: war trauma, forcibly displaced, intergenerational transmission, risk, protective

Antecedentes: A medida que el desplazamiento y la migración forzada exhiben de manera continua tendencias de crecimiento global, las nuevas y sobrevivientes generaciones de niños nacen y pasan sus años de formación en los países de acogida. Los niños refugiados que no han estado expuestos a eventos traumáticos aún pueden estar en riesgo de consecuencias adversas para el desarrollo y la salud mental a través de la transmisión intergeneracional del trauma.

Objetivo: Identificar y sintetizar mecanismos potenciales de transmisión intergeneracional de traumas en familias desplazadas por la fuerza donde los padres han experimentado una exposición directa al trauma relacionada con la guerra, pero los niños no tienen antecedentes de exposición directa al trauma.

Métodos: Se siguieron las pautas de revisión sistemática PRISMA. Las búsquedas se realizaron en siete bases de datos principales e incluyeron literatura sobre métodos cuantitativos, cualitativos y mixtos desde 1945 al 2019. La búsqueda resultó en 752 citas y 8 estudios (n = 1.684) cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión de la revisión.

Resultados: Los resultados sugieren que la exposición al trauma parental y las secuelas del trauma afectan indirectamente el bienestar del niño a través de mecanismos de apego inseguro; estilos de parentalidad maladaptativos; disminución de la disponibilidad emocional parental; disminución del funcionamiento familiar; acumulación de estresores familiares; estilos de comunicación intrafamiliar disfuncionales y gravedad de la sintomatología parental.

Conclusión: existe una clara necesidad de apoyar a los padres y a sus hijos que han estado expuestos a traumas de guerra. Se necesita más investigación para evaluar los efectos intergeneracionales independientes de la transmisión del trauma en esta población.

PALABRAS CLAVE: trauma de guerra, desplazados por la fuerza, transmisión intergeneracional, riesgo, protector

背景:随着流离失所和被迫移民继续呈现全球增长趋势, 新生代和幸存的儿童在东道国出生并度过了成长期。未经历创伤事件的难民儿童可能仍有通过代际创伤传递而面临不利发育和心理健康后果的风险。

目的:在父母经历过直接战争相关创伤暴露但孩子没有直接创伤暴露史的被迫流离失所的家庭中, 找出并综合得出代际创伤传递的潜在机制。

方法:遵循PRISMA系统综述指南。在七个主要数据库中进行了检索, 纳入了1945-2019年间的定量, 定性和混合方法文献。检索结果有752次引用, 其中8项研究 (n = 1,684) 符合综述纳入标准。

结果:研究结果表明, 父母的创伤暴露和创伤后遗症通过以下因素间接影响儿童的幸福感:不安全的依恋机制 ; 不良的养育方式 ; 减弱的父母有效情感 ; 降低的家庭功能 ; 家庭应激源的积累 ; 功能不良的家庭内部沟通方式和父母症状的严重程度。

结论:迫切需要支持遭受战争创伤的父母及其子女。需要进一步的研究来评估该人群中创伤传递的独立代际效应。

关键词: 战争创伤, 被迫流离失所, 代际传递, 风险, 保护性

1. Introduction

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that more than 70.8 million people have been forcibly displaced from their homes globally, due to protracted conflict, purposive violence, persecution and destruction. Unique constellations of events and stressors along migration trajectories place forcibly displaced individuals at an elevated risk for trauma exposure and trauma sequelae (Fazel, Reed, Panter-Brick, & Stein, 2012; Lustig et al., 2004; Miller & Rasco, 2004; Porter & Haslam, 2005; Siriwardhana, Ali, Roberts, & Stewart, 2014; Steel et al., 2009; Tyrer & Fazel, 2014). The long-term effects of myriad traumatic events and enduring sociopolitical stressors on refugee mental health have been the foci of considerable research across pre-, peri- and post-migration contexts – collectively termed the triple trauma paradigm (Miller & Rasco, 2004). A meta-analysis by Fazel, Wheeler, and Danesh (2005) comprising 20 studies (n = 6,743) reported that adult refugees resettled in high-income countries were ten times more likely to present with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) when compared with the general population. Refugee youth have also been reported as presenting with higher prevalence estimates of depression (Ellis, MacDonald, Lincoln, & Cabral, 2008; Heptinstall, Sethna, & Taylor, 2004; Hodes, Jagdev, Chandra, & Cunniff, 2008), PTSD (Bean, Derluyn, Eurelings-Bontekoe, Broekaert, & Spinhoven, 2007; Ellis et al., 2008; Geltman et al., 2005; Heptinstall et al., 2004; Reed, Fazel, Jones, Panter-Brick, & Stein, 2012) and other internalizing and externalizing problems (Bean et al., 2007; Nielsen, Nørredam, Christensen, Obel, & Krasnik, 2007; Reijneveld, de Boer, Bean, & Korfker, 2005), with age, gender and country of origin being reported as holding differential predictive validity for trauma-based psychological distress (Bronstein & Montgomery, 2011).

The extant literature base reporting associations between trauma exposure and adverse outcomes in refugee children is compelling, with type, duration and severity of trauma cumulatively associated with PTSD (Ellis et al., 2008; Eruyar, Maltby, & Vostanis, 2018; Qouta, Punamäki, & El Sarraj, 2003). These direct effects of war-related trauma exposure are further compounded by indirect effects via parental factors and parental responses to trauma (Bronstein & Montgomery, 2011). Indirect effects, or intergenerational transmission of trauma, describe the impact of traumatic events, experienced by a parent, on child development and wellbeing (Van Ee, Kleber, & Mooren, 2012). Research findings have illuminated direct and indirect pathways from parental psychopathology to higher levels of child hyperactivity and conduct, emotional and peer problems (Bryant et al., 2018; Eruyar et al., 2018). While the mechanisms via which these processes occur are less well understood, dyadic interactional disturbances are generally considered to play a key role in exacerbating the effects of trauma (Van Ee, Kleber, & Jongmans, 2016), with children who have been exposed to trauma, and who have parents with PTSD, being reported as more likely to exhibit insecure or ambivalent attachment styles (Bryant et al., 2018).

Despite the considerable literature base examining the effects of trauma on refugee mental health, there remains a relative paucity of literature synthesizing the indirect effects of parental trauma on child outcomes. Intergenerational transmission of trauma has been predominantly assessed via a diagnostic lens, with studies focusing on associations between parental mental health and child behaviours and wellbeing (Lambert, Holzer, & Hasbun, 2014). There is a marked need to integrate quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods findings in order to develop a more nuanced understanding of what is transmitted across generational fault lines and the process and mechanisms by which transmission occurs.

A recent systematic review by Sangalang and Vang (2017) (n = 20) set out to synthesize quantitative and mixed methods reports of psychosocial mechanisms of trauma transmission in refugee populations. The review highlighted parenting, family relationships and communication patterns as mechanisms of trauma transmission; however, nine of the twenty studies did not include details of a transmission mechanism. Of the twenty studies, fourteen studies assessed Holocaust samples, four studies sampled families living in post-conflict contexts and two studies comprised the same sample of children who had spent their formative years living under the Iraqi regime. Limitations in generalizing findings of Holocaust descendants to contemporary forcibly displaced groups were recently highlighted by Fazel (2019) as these groups are likely to have distinct experiences of trauma. Furthermore, methodological limitations, characteristic of Holocaust research including an over reliance on retrospective, second-generation, adult accounts of first-generation trauma; utilization of clinical samples; and a lack of matched controls (Kellerman, 2001) further limit the generalization of findings. Sixteen of the twenty studies assessed adult offspring therein precluding the identification of child-specific mechanisms. Finally, the two studies which comprised the Iraqi refugee sample did not control for direct trauma exposure in children, therein making it difficult to ascribe adverse child outcomes to an independent generational transmission effect.

In light of these current gaps in the literature, the present study set out to identify child-specific mechanisms of independent intergenerational trauma transmission by systematically reviewing studies of trauma transmission in forcibly displaced families in which children have no history of direct trauma exposure.

2. Method

2.1. Search strategy

Parallel searches were conducted across seven databases on 11 March, 2019. MEDLINE, ERIC, AMED, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science and PILOTS were systematically searched for English language, peer-reviewed articles with primary data from January 1945 up to March 2019. As an example, in Ebsco databases the following keyword search string was used: (‘generation*’ OR ‘intergenerational’ OR ‘crossgenerational’ OR ‘transgenerational’) AND (‘post traumatic’ OR posttraumatic OR ‘PTSD’ OR ((emotional OR collective OR anxiet* OR anxious* OR mental* OR behavio*) N3 (trauma* OR disorder* OR health OR distress* OR injur*)) OR psychosocial OR ‘psycho social’) AND (‘refuge*’ OR ‘asylum’ OR ‘asylumseeker*’ OR (displaced N3 (person* OR people*))).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Retrieved articles were screened against the following inclusion criteria:

Population: (i) Families with asylum-seeker or refugee protective status in which parents directly experienced forced displacement. The nomenclature ‘forcibly displaced individuals’ encompasses internally displaced people, unaccompanied minors, those who have crossed over the borders of their own country to seek asylum and refugees (recognized as meeting the terms of the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees) (UNHCR, 1951). Studies of internally displaced persons were excluded on the basis that they are less likely to experience the parameters of the triple trauma paradigm (Miller & Rasco, 2004).

(ii) Families must consist of two generations: parents and children, with parents aged over 18 years old and children aged 0–18 years old. Unaccompanied minors were excluded as they did not meet the criteria required to assess a generational transmission effect. In samples which included children born in the country of origin and in the host country, only findings from those born in the host country were considered to ensure no effects from direct trauma exposure. Studies employing a longitudinal design, where children were assessed from childhood into early adulthood were included to ascertain long-term effects of parental trauma on second-generation outcomes.

Exposure: (iiii) Parents had experienced direct exposure to war-related trauma (iv) Children had no history of any direct trauma exposure. Studies including children who had low levels of trauma exposure, but which statistically controlled for this exposure to assess independent transgenerational effects, were included.

Outcomes: (vi) Parental measure(s) of mental health or behaviour (vii) child measure(s) of mental health or behaviour (vii) measurement or discussion of mechanisms and covariates of trauma transmission. Together, parental trauma exposure and measures of subsequent mental health sequelae were considered as a proxy for ‘traumatisation’, with clinical or adverse outcomes at a second-generation level considered as indicators of a generational transmission effect.

Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies were included in the search strategy. The time limiter was selected to reflect the exclusion of Holocaust studies and the end of World War 2. Studies of intergenerational transmission of trauma in Holocaust samples post 1945 were additionally excluded per definition and in line with the aforementioned limitations (Fazel, 2019; Kellerman, 2001).

2.3. Screening process and data extraction

PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) were adhered to with the first and second author independently screening titles and abstracts of articles uploaded to Covidence (www.covidence.org) against study eligibility criteria. The screening process is summarised in Figure 1. Conflicts at the title and abstract screening level were discussed and resolved by the first two authors, and disagreements at the full-text screen were resolved via discussion by the first, second and final author. The remaining studies were independently checked for quality by the first and second author using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 (Hong et al., 2018) with the final author available to discuss potential conflicts. All studies passed the quality assessment and were retained for data extraction. Studies passed quality assessment if a theoretical framework, mechanisms and covariates of trauma transmission were detailed. The first and second author independently extracted data from studies regarding the country of study, country of origin, sample, assessment, trauma exposure, transmission model tested, main outcomes and identified mechanisms and covariates of transmission.

Figure 1.

PRISMA screening process.

3. Results

3.1. Description of included studies

Eight studies examining seven independent samples (n = 1,684) were included in the present review. Table 1 summarises descriptive details and aims of these studies. Three studies comprised a mixed methods approach. Studies 1 and 2 combined qualitative and quantitative approaches in exploring interrelations of transmission and study 8 utilised observational and quantitative methods. Studies (3–7) employed quantitative methods. Seven studies assessed refugee samples and one study assessed a mixed refugee and asylum-seeking sample. Table 2 reports details of parent and child trauma exposure.

Table 1.

Overview of studies included in thesystematic review.

| Citation and year | Country of study | Population | Design | Country of origin | Sample size | Child demographics | Parent demographics | Main study aims and associated measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1. Dalgaard and Montgomery (2017) |

Denmark | Refugees | Cross sectional Mixed methods |

Afghanistan Iran Iraq Lebanon Palestine Syria |

N = 86 | Aged 4–9 yrs 47% female 53% male |

87% two-parent families 13% single parent families |

To explore the role of family functioning in trauma transmission (interviews) and to test associations of emergent descriptive categories of family functioning with child psychosocial adjustment (SDQ) | |||

| Study 2. Dalgaard, Todd, Daniel, and Montgomery (2016) |

Denmark | Refugees | Cross sectional Mixed methods |

Afghanistan Iran Iraq Lebanon Palestine Syria |

N = 86 | Aged 4–9 yrs 47% female 53% male |

87% two-parent families 13% single parent families |

To explore potential risk and protective factors for trauma transmission by examining associations between intra-family communication styles (interviews), children’s psychosocial adjustment (SDQ) and attachment security (ATST) | |||

| Study 3. East, Gahagan, and Al-Delaimy (2018) |

USA of America | Refugees | Cross sectional Quant |

Somalia | N = 396 | Mean age: 10.4 yrs 56% male 44% female |

Mean age: 39.4 yrs Married: 91% Mean years in the US: 13.7 yrs |

To identify associations between maternal trauma, posttraumatic stress (HTQ), and mental health (HSCL-25), and child mental health (CDI-2) and adjustment (PRS-C, MPVS) | |||

| Study 4. Field and Muong (2013) |

USA of America | Refugee | Cross sectional Quant |

Cambodia | N = 64 | Mean age: 16.7 yrs 31% males 69% females |

Mean age: 47.5 yrs Married: 52.75% Mean years since immigration: 22.96 yrs |

To examine parenting styles as a mechanism underlying trauma transmission in treatment seeking v. non-treatment seeking groups. Assessed parenting styles included over-protective and rejecting (PBI) and role-reversing (RPS) styles | |||

| Study 5. Han (2006) |

USA of America | Refugees | Cross sectional Quant |

Vietnam Laos Cambodia |

N = 118 | 67% females 33% males 100% University students |

100% two-parent families | To examine the effect of parental trauma (HTQ) on second generation sense of coherence (SOC), as mediated by parent–child attachment (PBI) | |||

| Study 6. Sangalang, Jager, and Harachi (2017) |

USA of America | Refugees | Longitu-dinal Quant |

Cambodia Vietnam |

N = 654 | Mean age: 12 yrs 51% female 49% male |

Mean age: 42 yrs Married: 60% Mean years in the US: 13.63 yrs |

To examine the longitudinal effects of maternal traumatic distress (HTQ) on family functioning (likert scales) and child adjustment (likert scales) | |||

| Study 7. Vaage et al. (2011) |

Norway | Refugees | Longitu-dinal Quant |

Vietnam | N = 198 | Mean age: 12.8 yrs 46% female 54% male |

Mothers mean age:

40.3 yrs Fathers mean age: 45.8 yrs 90% two parent families 10% single parent families |

To study the association between parental psychological distress (SCLR-90) and child outcomes (SCLR-90, SDQ) 23 years post displacement | |||

| Study 8. Van Ee et al. (2012) |

Netherlands | Refugees & asylum-seekers | Cross sectional Mixed methods |

Asia Middle -East Africa Eastern-Europe Russia Former -Russia |

N = 98 | Mean age: 26.6mths 57% male 43% females |

Mean age: 29.5 yrs Mean yrs in Netherlands: 5.5 yrs 53% refugee status 47% seeking asylum |

To analyse the interrelations between maternal posttraumatic stress symptoms (HTQ, HSCL-25), parent–child interaction (observational methods – EAS), infant’s psychosocial functioning (CBCL 1,5–5) and development (BSID) | |||

Abbreviations: Strengths and difficulties (SDQ), Attachment and Traumatisation Story Task (ATST), Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25), Children’s Depression Inventory-2 (CDI-2), Perceived Racism Scale-Children (PRS-C), Multicultural Peer Victimization Scale (MPVS), Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI), Relationship with Parents Scale (RPS), Sense of coherence (SOC), Symptom Check List-90-Revised (SCLR-90), Emotional availability scales (EAS), Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL 1,5–5), Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID).

Table 2.

Parent and child trauma exposure.

| Citation and year | Parent trauma exposure | Child trauma exposure |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1. Dalgaard & Montgomery (2017) |

37% families: one parent with trauma

exposure 63% families: both parents with trauma exposure |

No direct trauma |

| Study 2. Dalgaard et al. (2016) |

37% families: one parent with trauma

exposure 63% families: both parents with trauma exposure |

No direct trauma |

| Study 3. East et al. (2018) |

Prolonged stays in refugee camp:

(M = 7.3 yrs) Torture |

Experienced, witnessed or heard details of few traumas, but effects were statistically controlled for in final analysis |

| Study 4. Field et al. (2013) |

Khmer Rouge regime | No direct trauma |

| Study 5. Han (2006) |

Political instability Communist regime War trauma |

No direct trauma |

| Study 6. Sangalang et al. (2017) |

War trauma | No direct trauma |

| Study 7. Vaage et al. (2011) |

War trauma Communist regime |

No direct trauma |

| Study 8. Van Ee et al. (2012) |

Imprisonment (39%) being wounded (31%) combat situations (47%) rape (25%) murder of a relative or friend (40%) murder of a stranger (27%) torture (44%) |

No direct trauma |

3.2. Transmission: mechanisms and covariates

Main findings are summarised in Table 3. Five studies (3–6, 8) tested mediational hypotheses of transmission with a view to elucidating mechanisms of transmission. Studies 4–5 met pre-conditions for mediation and identified mechanism are therefore observed mechanisms. Studies 3, 6, 8 did not meet pre-conditions for mediation with parental trauma and mental health variables being indirectly linked to child outcome variables. In these studies, tested mediating variables are potential mechanisms. Studies 1–2, 7 presented correlational findings between parental trauma sequelae, family- and parent-related variables and child outcome measures. Variables which significantly correlate with child outcome measures are discussed as potential mechanisms. For presentation purposes, and due to only eight studies meeting review inclusion parameters, the distinction between observed and potential mechanisms is made here but is not carried throughout the remainder of the results section.

Table 3.

Transmission frameworks, potential mechanisms and findings.

| Citation and Year | Theoretical framework

underpinning Method |

Main Findings | Identified mechanism of transmission | Risk factor(s)/covariates | Protective factor(s) | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1. Dalgaard and Montgomery (2017) |

Family functioning theory: Circumplex model; McMaster model; ABC-X family crisis model. |

Family stressors were the strongest predictor of

higher difficulty scores (n = 14

families) Clinically meaningful difference in mean SDQ difficulty scores between children in families with marital conflict, and those without 22% of variance in SDQ scores explained by role-reversal parenting and accumulation of family stressors Composite measure of adaptive family functioning associated with lower SDQ scores |

Disrupted family functioning | Stressor pile-up Parent–child role reversal Marital conflict Having 2 trauma exposed parents |

Family flexibility Family cohesion |

Yes٭ |

| Study 2. Dalgaard et al. (2016) |

Attachment theory | Negative association between child attachment

security (ATST) and total difficulty scores (SDQ) Sig. negative association between child attachment security and externalizing SDQ scores Sig. association between intra family communication style and child attachment style Sig. association between child attachment style and family presence of an unfiltered communication style Modulated disclosure may be associated with secure attachment |

Disrupted attachment representations | Unfiltered speech Insecure attachment |

Modulated disclosure | Yes٭ |

| Study 3. East et al. (2018) |

Attachment theory | Maternal torture sig. related to maternal

withdrawal/detachment symptoms Sig. indirect effects of maternal torture on all child outcomes via mothers’ depressed mood Sig. indirect effect of maternal torture on child victimization via mothers’ volatility/panic symptoms |

Mothers’ mental health symptoms | Maternal torture Torture sequelae |

Mothers’ adaptive functioning | No |

| Study 4. Field et al. (2013) |

Attachment theory | Sig. relationships reported between social support

and PTSD, and mothers’ level of education and PTSD All PTSD subscale scores sig. correlated with role reversal and rejecting parenting Rejecting parenting sig. correlated with child anxiety Role reversal sig. correlated with child anxiety and depression Role reversing parenting mediated the relationship between (all sub-scales of) mothers’ PTSD and child anxiety, but did not fully explain the relationship |

Attachment & parenting styles | Role reversal parenting Rejecting parenting |

Maternal education Social support |

Yes |

| Study 5. Han (2006) |

Attachment theory Shattered assumptions theory Salutogenic theory |

Perceived parental trauma sig. predicted

attachment Perceived parental trauma was negatively associated with SOC Parent–child attachment positively predicted adolescents’ SOC Parent–child attachment played a fully mediational role between parental trauma and SOC |

Disrupted attachment representations | Insecure attachment | Secure attachment | No |

| Study 6. Sangalang et al. (2017) |

Family functioning theory | Mothers of US born children reported sig higher

levels of TD and parent–child conflict US born children reported higher levels of anti-social behaviour Weaker family functioning was sig. associated with elevated levels of depressive symptoms, antisocial and delinquent behaviour Maternal (TD) was indirectly linked to child MH outcomes: For foreign born children (outside US), maternal TD was sig. associated with diminished family functioning and increased school problems Maternal TD was indirectly associated with child depressive symptoms and antisocial and delinquent behaviour, via diminished family functioning in foreign born children |

Disrupted family functioning | Diminished family functioning | - | No |

| Study 7. Vaage et al. (2011) |

Family systems theory | 30% of families had one parent with a high

psychological distress score (probable caseness) Sig. positive association between older childrens’ probable caseness and their fathers’ probable caseness Children (10–18 yrs) of fathers with a large family network (10+ members) in Norway reported lower problem mean scores Fathers’ social network (Norweigan friends) at T2 was sig positively associated with child outcomes at T3 Paternal PTSD at T1 was sig negatively associated with child MH @ T3 |

Disrupted family systems | Paternal PTSD | Social networks Early integration in host country |

No |

| Study 8. Van Ee et al. (2012) |

Attachment theory | Higher levels of mothers’ post traumatic stress

symptoms were sig associated with higher levels of psychosocial problems in

children Severity of PTSS was sig correlated with infants’ internalizing behaviours and total problems Mothers experiencing PTSS scored lower on all EA scales Higher levels of mothers’ post traumatic stress symptoms were sig associated with higher levels of insensitive, unstructured and hostile interactions Infants whose mothers reported higher levels of PTSS demonstrated lower levels of responsiveness and involvement |

Disrupted attachment systems | Symptom severity Unstructured, hostile & in sensitive parenting Diminished maternal emotional availability |

Caregiver self-regulation | No |

Abbreviations: Significant (sig.), Sense of coherence (SOC), Attachment and traumatisation story task (ATST), Strengths and difficulties (SDQ), Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Mental health (MH), Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), Emotional availability (EA), Traumatic distress (TD).

٭Control only extends to the quantitative measure of adjustment – SDQ scores were compared to Danish norms.

None of the included studies defined a priori risk factors but instead discussed observed independent variables as covariates or post hoc risk factors for a generational transmission of trauma. Similarly, none of the included studies set out to assess a priori defined protective factors but instead inferred protective effects of examined variables in the absence of an observed covariance between parental trauma and adverse child outcomes. As six of the eight studies were cross-sectional in design (studies 1–5, 8), causality could not be established, and risk and protective effects are inferred. As such, independent variables in studies 1–5 and 8 were considered as covariates of a generational transmission, with independent variables in studies 6 and 7 considered as risk or protective factors.

3.2.1. Dyadic interactions

Studies (2, 4, 5, 8) examined the direct effects of dyadic interactions on second-generation outcomes and the indirect effects of maternal measures on second-generation scores via the quality of parent–child interactions. Overall, disrupted dyadic interactions were proffered as a mechanism of intergenerational trauma transmission, with insecure attachment, maladaptive parenting and diminished parental emotional availability being reported as covariates of transmission. Dyadic attachment representations were investigated via qualitative and observational methods in studies 2 and 8, both assessing the youngest samples in the review. Study 2 reported insecure attachment as a covariate of a generational transmission of trauma and further reported a negative association between child attachment security and total difficulty scores. Additionally, a significant negative association was found between child attachment security and externalizing difficult behaviours. Study 8 reported that mothers experiencing post-traumatic stress symptoms scored lower on all emotional availability scales and that symptom severity was significantly associated with higher levels of insensitive, unstructured and hostile interactions. Additionally, children of mothers with higher levels of symptom severity demonstrated lower levels of responsiveness and involvement. Together, studies 2 and 8 indicate that maternal trauma can negatively shape dyadic attachment and correlate with adverse outcomes in non-trauma-exposed children from a very young age.

Studies 4 and 5 assessed parenting styles and parent–child relationships in adolescent samples. Study 4 reported PTSD to be significantly correlated with role-reversing and rejecting parenting, and in turn, rejecting and role-reversing parenting were significantly correlated with child anxiety, and child anxiety and depression, respectively. Role-reversing parenting was found to partially mediate the relationship between mothers’ PTSD and child anxiety. Study 5 reported perceived parental trauma to significantly predict attachment, with attachment positively predicting adolescents’ sense of coherence and fully mediating the association between parental trauma and adolescents’ sense of coherence.

Conversely, review studies inferred that the capacity to; engender secure attachment representations (study 5) and interact with infants in a sensitive and responsive manner (study 8), to be protective against trauma transmission. Finally, it is noteworthy that only one study (study 2) included a measure specifically developed to assess attachment in refugee youth.

3.2.2. Family functioning

Three studies (1, 6, 7) incorporated a family systems approach in elucidating covariates and risk factors for trauma transmission. A range of variables were collected across studies to assess overall family functioning. These included; family flexibility, stressor pile-up, marital problems (study 3), parent–child conflict, family cohesion, parental involvement (study 6) and family presence in the host country (study 7). Overall, studies reported a negative impact of reduced family functioning on trauma transmission, with diminished family functioning being reported as a mechanism of transmission and as being significantly associated with elevated levels of second-generation depressive symptoms and antisocial and delinquent behaviours (study 6). Moreover, marital conflict and an accumulation of family stressors were associated with child total difficulty scores (study 1). Role-reversing parenting and an accumulation of family stressors were found to explain 22% of the variance in reported SDQ scores. Conversely, a lack of observed transmission was explained in terms of enhanced familial functioning and high levels of family flexibility and cohesion. Study 7 did not find any negative associations between tested family-related variables and child outcomes but reported having a large family network in the host country as protective against generational transmission, with children of fathers with a large family network reporting lower problem mean scores.

3.2.3. Intra-family communication styles

Study 2 investigated the effects of communication styles, namely, open communication, modulated disclosure, unfiltered speech and silencing, on trauma transmission, as indexed by child attachment and adjustment. An association was reported between child attachment style and whether the family demonstrated an unfiltered communication style. Modulated disclosure was proffered to be associated with secure attachment and therein to have a potentially buffering effect. However, this finding did not reach significance, with the absence of significance being attributed to sample size.

3.2.4. Parental trauma history and symptomology

Four of the seven independent samples tested direct effects of parental trauma on second-generation outcomes or indirect effects of parental trauma on second-generation problems via parental symptomology. Parental trauma, e.g. torture (study 3); having two traumatised parents (study 1); trauma sequelae, e.g. depression (study 3), PTSD (studies 7, 8) and symptom severity (study 8) were reported as covariates of, or risk factors for, transmission. Study 7 reported paternal PTSD as a significant risk factor for negative second-generation health outcomes over time, and paternal psychological distress was significantly associated with psychological distress in older children. Study 8 reported a direct, significant effect of mothers’ post-traumatic stress symptoms on infants’ psychosocial problems. Study 3 reported indirect effects of maternal torture on all child outcomes via maternal withdrawal and detachment, and of maternal torture on children's’ experiences of bullying and victimization via mothers’ volatility and panic.

3.2.5. Identification of protective factors

Four studies (3, 4, 6, 7) described the potentially protective effects of several parent and family factors. Maternal adaptive functioning post-trauma (study 3), higher levels of maternal education and perceived social support (study 4) and higher levels of economic, peer and community support (studies 6, 7) were all suggested as buffering the effects of parental trauma on second-generation outcomes. Study 7 highlighted early integration into host communities as having protective effects over time with fathers’ social network being significantly associated with positive child outcomes.

4. Discussion

The present paper is the first to systematically review studies investigating intergenerational transmission of trauma in asylum-seeking and refugee families in which children do not have a history of direct trauma exposure. Consequently, and in contrast to Sangalang and Vang (2017) review, an examination of independent intergenerational effects of trauma transmission was possible. Additionally, only studies with child and youth second-generation samples were included to garner a greater understanding of developmental transmission mechanisms. Overall, findings suggest that parental trauma exposure and ensuing trauma sequelae indirectly affect child well-being via insecure attachment; maladaptive parenting styles; diminished parental emotional availability; decreased family functioning; accumulation of family stressors; dysfunctional intra-family communication styles and severity of parental trauma and symptomology. Conversely, high levels of family functioning, dyadic attunement, child-centred communication styles and social support networks seem to buffer the effects of parental trauma and trauma sequelae on child outcomes. All review studies reported a generational transmission effect wherein higher levels of parental trauma and trauma sequelae were associated with higher levels of second-generation mental health or behavioural problems.

As reported by Sangalang and Vang (2017) and as echoed in the broader intergenerational trauma field (Dashorst, Mooren, Kleber, de Jong, & Huntjens, 2019), the reviewed studies were consistent in reporting parent- and family-related variables as the most salient mechanisms of transmission. This confers the findings reported by Sangalang and Vang (2017) and demonstrates that the same factors may serve as mechanisms for trauma transmission regardless of whether a child has been trauma-exposed and irrespective of children's’ age. In a similar vein, the factors asserted in the present review to be protective against intergenerational transmission of trauma, e.g. higher levels of perceived support have been reported elsewhere in the broader PTSD and relational literature (Thabet, Ibraheem, Shivram, Winter, & Vostanis, 2009), with the present review additionally finding early integration to be protective against second-generation psychological distress (Vaage et al., 2011).

It is of note that although the present findings are in line with the theoretical assumptions underpinning intergenerational trauma transmission (Danieli, 1998), they also reflect broader attachment and family system literature in that, disrupted attachment, maladaptive parenting, parental mental health symptomology and diminished family functioning are likely to precede child difficulties and adverse outcomes across myriad trauma-exposed and non-trauma-exposed populations (Palosaari, Punamäki, Qouta, & Diab, 2013; Van Ee et al., 2016). Thus, the unfavourable second-generation outcomes reported in the reviewed studies may be due to factors other than a generational transmission effect, e.g. exposure to acculturation stressors (Fazel, 2019), having a parent with PTSD (Van Ee et al., 2016), or individual and familial resiliency and vulnerability factors (Yehuda, Flory, Southwick, & Charney, 2006). Given that asylum-seeking and refugee families with trauma-exposed parents and non-trauma-exposed children represent a unique subset of today’s forcibly displaced population, it is surprising that studies largely do not report mechanisms of transmission specific to this group. This may be explained by a lack of assessments of trauma exposure and stressors throughout the triple trauma paradigm and contextual framing regarding the protective status of samples.

4.1. Triple trauma paradigm

Forcibly displaced individuals are at an elevated risk of experiencing numerous traumatic events (Miller & Rasco, 2004). However, the reviewed studies predominantly focused on pre-migratory traumas. Only one study (study 3) included peri-migration information as indexed by a number of years spent in a refugee camp. Social dissolution and living in legal grey zones for indeterminate periods of time affect individual and communal coping mechanisms (Afifi, Afifi, Merrill, & Nimah, 2016), and may arguably exert enduring effects on dyadic attunement and parenting practices should these individuals have children in the future. Post-migration asylum-seeking contexts are characterized by diverse sets of acculturation stressors; however, none of the reviewed studies included assessments of current stressors for parent and child. By incorporating measures of current stressors in future research, post-migration, context-specific mechanisms can be explored. Grouping participants or studies according to displacement contexts and post-migration stressors can further elucidate mechanisms for transmission with study 1 reporting enduring stressors to ‘matter more to the well-being of their children than the parental traumatic past.’ (Dalgaard & Montgomery, 2017, p. 297).

4.2. Protective status and legal frameworks

The protective status of an individual speaks to the rights and entitlements of that individual in the host country. There is no singular legal policy governing the granting of asylum resulting in wide disparities in experiences in terms of application procedures, accommodation conditions and access to services (European Council, 2019). Acknowledgement of these contextual factors is imperative given that living in uncertainty, punitive asylum protocols, and prolonged wait times for protective status adjudications could compound the effects of trauma exposure and mental health sequelae (Porter & Haslam, 2005) and are likely to affect trauma transmission. The reviewed studies did not specify whether ‘refugee’ samples met the articles of the Geneva Convention. In study 1, examples of family stressors included worries about residency permits and citizenship which may convey that some participants did not have refugee status. Study 8 was the only study to distinguish between asylum-seeking and refugee participants. Though they did not test for group differences, asylum-seeking mothers may be less emotionally available to their children due to the stress and cognitive demands inherent in the asylum process.

5. Implications

Findings of the present review have implications for clinical practice. Families in which one or both parents have a history of trauma exposure should be assessed and prioritized based on the presented risk and protective factors. In cases where risk is substantial, individual or family therapy can be centred around the identified mechanisms of transmission in a psychoeducational or family system format. Multi-level interventions can be tailored to a family’s history, context and overall functioning with a view to safeguarding children against enduring effects of parental trauma. As the present review synthesizes mechanisms and covariates of transmission in families with very young children, findings can be translated to developmentally appropriate intervention strategies and supportive policies. Finally, findings from the current review have implications for host society trauma-focused organizations and governmental bodies. Specifically, to inform policy by way of informing vulnerability assessments as enshrined in European and International law (European Council, 2013).

6. Limitations

The organization of transmission mechanisms is hampered due to substantial heterogeneity across samples; a focus on pre-migratory trauma and parental PTSD as predictors of second-generation difficulties; a lack of culturally validated measures and a quantitative focus across methodologies. Moreover, there is a risk of bias within and across studies as a function of mixed methods and a wide range of reported outcomes. There is also a possible risk of reporting bias inter alia, the likelihood of studies with non-significant results being published. This may be applicable to the present review as review parameters only included peer-reviewed, empirical research. The included studies are primarily cross-sectional in nature which limits causal inference and a deeper understanding of what constitutes risk and protective factors for transmission. These points, in addition to only eight studies assessing or controlling for direct child trauma exposure, limit inter-study comparability and the extrapolation of findings to wider migration and displacement contexts. Finally, although every effort was made to include studies which reflect contemporaneous conflict, migration and post-displacement contexts, all countries of study share Western, high-income profiles. As 80% of forcibly displaced individuals seek refuge in countries bordering their countries of origin, and as these are generally low-middle income countries (UNHCR, 2019), the countries of study and countries of origin included in the present review mostly do not reflect current displacement and migration trends.

7. Recommendations for future research

Although the present review set out to identify and synthesize potential mechanisms of intergenerational trauma transmission, the search highlighted several salient points which must be addressed in order to advance the utility of future research. Given the magnitude and permeating nature of displacement and migration, it is striking that review parameters identified only eight studies which assessed or controlled for direct child trauma exposure. Further research assessing trauma transmission in families with non-trauma-exposed children is warranted and should incorporate prospective, longitudinal designs. Studies should set out a priori mechanisms of transmission and test these mechanisms using formal mediation analyses. Further examination of any of the identified potential mechanisms from the present review, for example, attachment style, parenting style, parental emotional availability, family functioning and family communication styles, would benefit this field. Moreover, culturally appropriate measures assessing trauma, trauma sequelae and child outcomes are required. Finally, there is a distinct need to include protective status information of samples and details of trauma exposure throughout the migratory journey to allow for a more detailed examination of the effects of contextual factors on transmission. Testing for group differences (asylum-seeker v. refugee) would allow for a more nuanced understanding of how immigration factors can influence transmission in post-migration settings.

8. Conclusion

This is the first review to evaluate and synthesize mechanisms of intergenerational trauma transmission in asylum-seeking and refugee families in which children have no history of direct trauma exposure. Studies reported diverse but unfavourable effects of parental trauma and trauma sequelae on second-generation outcomes by way of parent- and family-related mechanisms. As only eight studies met the criteria to assess independent, intergenerational effects, there is a distinct need for additional, contextualized, culturally appropriate research to further extant knowledge and to promote the wellbeing of refugee children and reduce intergenerational continuities of trauma.

Funding Statement

CONTEXT has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 722523.

Disclosure statement

The researchers declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Afifi, T. D., Afifi, W. A., Merrill, A. F., & Nimah, N. (2016). ‘Fractured communities’: Uncertainty, stress, and (a lack of) communal coping in Palestinian refugee camps. Journal Of Applied Communication Research, 44(4), 343–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, T., Derluyn, I., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., Broekaert, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2007). Comparing psychological distress, traumatic stress reactions, and experiences of unaccompanied refugee minors with experiences of adolescents accompanied by parents. The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease, 195(4), 288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein, I., & Montgomery, P. (2011). Psychological distress in refugee children: A systematic review. Clinical Child And Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R. A., Edwards, B., Creamer, M., O’Donnell, M., Forbes, D., Felmingham, K. L., … Van Hooff, M. (2018). The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on refugees’ parenting and their children’s mental health: A cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 3(5), e249–e258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard, N. T., & Montgomery, E. (2017). The transgenerational transmission of refugee trauma: Family functioning and children’s psychosocial adjustment. International Journal Of Migration, Health And Social Care, 13(3), 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard, N. T., Todd, B. K., Daniel, S. I., & Montgomery, E. (2016). The transmission of trauma in refugee families: Associations between intra-family trauma communication style, children’s attachment security and psychosocial adjustment. Attachment & Human Development, 18(1), 69–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danieli, Y. (Ed.). (1998). International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Dashorst, P., Mooren, T. M., Kleber, R. J., de Jong, P. J., & Huntjens, R. J. (2019). Intergenerational consequences of the Holocaust on offspring mental health: A systematic review of associated factors and mechanisms. European Journal Of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1654065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East, P. L., Gahagan, S., & Al-Delaimy, W. K. (2018). The impact of refugee mothers’ trauma, posttraumatic stress, and depression on their children’s adjustment. Journal Of Immigrant And Minority Health, 20(2), 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, B. H., MacDonald, H. Z., Lincoln, A. K., & Cabral, H. J. (2008). Mental health of Somali adolescent refugees: The role of trauma, stress, and perceived discrimination. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eruyar, S., Maltby, J., & Vostanis, P. (2018). Mental health problems of Syrian refugee children: The role of parental factors. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(4), 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Council . (2013). Reception conditions directive. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013L0033&from=EN

- European Council . (2019). Asylum procedures. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/asylum/common-procedures_en

- Fazel, M. (2019). Focusing a lens on refugee families to address layers of avoidance. The Lancet Public Health, 4(7), e318–e319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, M., Reed, R. V., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379(9812), 266–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, M., Wheeler, J., & Danesh, J. (2005). Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. The Lancet, 365(9467), 1309–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field, N. P., Muong, S., & Sochanvimean, V. (2013). Parental styles in the intergenerational transmission of trauma stemming from the khmer rouge regime in Cambodia. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(4), 483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geltman, P. L., Grant-Knight, W., Mehta, S. D., Lloyd-Travaglini, C., Lustig, S., Landgraf, J. M., & Wise, P. H. (2005). The “lost boys of Sudan”: Functional and behavioral health of unaccompanied refugee minors resettled in the USA. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159(6), 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, M. (2006). Relationship among perceived parental trauma, parental attachment, and sense of coherence in Southeast Asian American college students. Journal of Family Social Work, 9(2), 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Heptinstall, E., Sethna, V., & Taylor, E. (2004). PTSD and depression in refugee children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 13(6), 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodes, M., Jagdev, D., Chandra, N., & Cunniff, A. (2008). Risk and resilience for psychological distress amongst unaccompanied asylum seeking adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(7), 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., … Rousseau, M. C. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Montreal, Canada: IC Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman, N. P. (2001). Psychopathology in children of Holocaust survivors: A review of the research literature. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 38(1), 36–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, J. E., Holzer, J., & Hasbun, A. (2014). Association between parents’ PTSD severity and children’s psychological distress: A meta‐analysis. Journal Of Traumatic Stress, 27(1), 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig, S. L., Kia-Keating, M., Knight, W. G., Geltman, P., Ellis, H., Kinzie, J. D., … Saxe, G. N. (2004). Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. Journal Of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 24–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. E., & Rasco, L. M. (2004). An ecological framework for addressing the mental health needs of refugee communities. In Miller K. E. & Rasco L. M. (Eds.), The mental health of refugees: Ecological approaches to healing and adaptation (pp. 1–64). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S. S., Nørredam, M., Christensen, K. L., Obel, C., & Krasnik, A. (2007). The mental health of asylum-seeking children in Denmark. Ugeskrift For Laeger, 169(43), 3660–3665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palosaari, E., Punamäki, R. L., Qouta, S., & Diab, M. (2013). Intergenerational effects of war trauma among Palestinian families mediated via psychological maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(11), 955–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M., & Haslam, N. (2005). Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 294(5), 602–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta, S., Punamäki, R. L., & El Sarraj, E. (2003). Prevalence and determinants of PTSD among Palestinian children exposed to military violence. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 12(6), 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, R. V., Fazel, M., Jones, L., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in low-income and middle-income countries: Risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379(9812), 250–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijneveld, S. A., de Boer, J. B., Bean, T., & Korfker, D. G. (2005). Unaccompanied adolescents seeking asylum: Poorer mental health under a restrictive reception. The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease, 193(11), 759–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangalang, C. C., Jager, J., & Harachi, T. W. (2017). Effects of maternal traumatic distress on family functioning and child mental health: An examination of Southeast Asian refugee families in the US. Social Science & Medicine, 184, 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangalang, C. C., & Vang, C. (2017). Intergenerational trauma in refugee families: A systematic review. Journal Of Immigrant And Minority Health, 19(3), 745–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siriwardhana, C., Ali, S. S., Roberts, B., & Stewart, R. (2014). A systematic review of resilience and mental health outcomes of conflict-driven adult forced migrants. Conflict And Health, 8(1), 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z., Chey, T., Silove, D., Marnane, C., Bryant, R. A., & Van Ommeren, M. (2009). Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 302(5), 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabet, A. A., Ibraheem, A. N., Shivram, R., Winter, E. A., & Vostanis, P. (2009). Parenting support and PTSD in children of a war zone. International Journal Of Social Psychiatry, 55(3), 226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer, R. A., & Fazel, M. (2014). School and community-based interventions for refugee and asylum seeking children: A systematic review. PloS One, 9(2), e89359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR . (1951). Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/en-ie/3b66c2aa10 [PubMed]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) . (2019). Figures at a glance. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/en-ie/figures-at-a-glance.html

- Vaage, A. B., Thomsen, P. H., Rousseau, C., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Ta, T. V., & Hauff, E. (2011). Paternal predictors of the mental health of children of Vietnamese refugees. Child And Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 5(1), 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ee, E., Kleber, R. J., & Jongmans, M. J. (2016). Relational patterns between caregivers with PTSD and their nonexposed children: A review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(2), 186–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ee, E., Kleber, R. J., & Mooren, T. T. (2012). War trauma lingers on: Associations between maternal posttraumatic stress disorder, parent–child interaction, and child development. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33(5), 459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda, R., Flory, J. D., Southwick, S., & Charney, D. S. (2006). Developing an agenda for translational studies of resilience and vulnerability following trauma exposure. Annals Of The New York Academy Of Sciences, 1071(1), 379–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]