COR27 and COR28 act as key regulators in the COP1–HY5 regulatory hub by regulating HY5 activity to ensure proper skotomorphogenic growth in the dark and photomorphogenic development in the light.

Abstract

Plants have evolved sensitive signaling systems to fine-tune photomorphogenesis in response to changing light environments. Light and low temperatures are known to regulate the expression of the COLD REGULATED (COR) genes COR27 and COR28, which influence the circadian clock, freezing tolerance, and flowering time. Blue light stabilizes the COR27 and COR28 proteins, but the underlying mechanism is unknown. We therefore performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using COR27- and COR28 as bait and identified the E3 ubiquitin ligase CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1) as an interactor. COR27 and COR28 physically interact with COP1, which is in turn responsible for their degradation in the dark. Furthermore, COR27 and COR28 promote hypocotyl elongation and act as negative regulators of photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). Genome-wide gene expression analysis showed that HY5, COR27, and COR28 co-regulate many common genes. COR27 interacts directly with HY5 and associates with the promoters of the HY5 target genes HY5 and PIF4, then regulates their transcription together with HY5. Our results demonstrate that COR27 and COR28 act as key regulators in the COP1–HY5 regulatory hub, by regulating the transcription of HY5 target genes together with HY5 to ensure proper skotomorphogenic growth in the dark and photomorphogenic development in the light.

INTRODUCTION

Light is critical for plants, not only as an energy source for photosynthesis, but also because it regulates the plant development program known as photomorphogenesis. In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), at least five types of photoreceptors are involved in the regulation of overlapping physiological functions essential to plant development, such as de-etiolation and photoperiodic flowering. The main photoreceptors include blue light photoreceptors, known as “cryptochromes” (CRYs; Lin, 2002); the red/far-red light photoreceptors, called “phytochromes” (Phys; Quail, 2002); the blue light/UV-A photoreceptors phototropin (Briggs and Christie, 2002); the LOV-domain/F-box proteins ZEITLUPE, FLAVIN BINDING, KELCH REPEAT, F-BOX PROTEIN1, and LOV KELCH PROTEIN2 (Demarsy and Fankhauser, 2009); and the UV-B photoreceptor UV RESISTANCE LOCUS8 (UVR8; Rizzini et al., 2011).

Photomorphogenesis is critical for seedling development. Buried seeds will germinated into etiolated seedlings that develop long hypocotyls, keep their cotyledons closed, and maintain curved apical hooks to emerge from the soil unscathed. However, once they reach the soil surface, hypocotyl elongation is inhibited while cotyledons quickly expand in response to light (Sullivan and Deng, 2003). Many key factors have been reported to be involved in de-etiolation. CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1) is a RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase that acts downstream of the Phys, CRYs, and UVR8 (Ang and Deng, 1994; Christie et al., 2012). COP1 is responsible for the degradation of various photomorphogenesis-promoting transcription factors in the dark, including the bHLH transcription factor LONG HYPOCOTYL IN FAR RED1 and the basic Leu-zipper factor ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 (HY5; Yi and Deng, 2005; Jiao et al., 2007; Foreman et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011), thus promoting skotomorphogenesis (seedling development in the dark; Lau and Deng, 2012). Arabidopsis cop1 mutant seedlings exhibit a COP1 phenotype, with expanded cotyledons and short hypocotyls even when grown in constant darkness (Deng et al., 1991). The COP1-related protein SUPPRESSOR OF PHYTOCHROME A (SPA1) interacts with COP1 to positively regulate COP1 activity, whereas CRYs and Phys suppress the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of COP1 by forming a complex with SPA1 and COP1 in a light–dependent manner (Deng et al., 1991; Lian et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011; Zuo et al., 2011).

The perception of light by the photoreceptors results in the regulation of the activity of many transcription factors. For example, CRYs interact with the transcription factors CRYPTOCHROME-INTERACTING BASIC-HELIX-LOOP-HELIX1 and PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR (PIF) PIF4 and PIF5 to regulate transcription (Liu et al., 2008, 2013a, 2013b; Ma et al., 2016; Pedmale et al., 2016). Similarly, Phys also interact with PIFs to regulate transcription (Ni et al., 1998; Leivar and Quail, 2011). HY5 promotes photomorphogenesis downstream of CRYs, Phys, and UVR8, and plays a critical role during de-etiolation (Jiao et al., 2007). In the dark, HY5 is a target of COP1 and is degraded via the proteasome, but remains highly abundant in the light, as COP1 is repressed by the photoreceptors (Osterlund et al., 2000; Hoecker, 2017; Podolec and Ulm, 2018). HY5 positively or negatively regulates the expression of over 3,000 genes, a large fraction of which are involved in photomorphogenesis (Zhang et al., 2011). HY5 is also involved in a positive feedback loop promoting COP1 transcription by binding to its promoter (Huang et al., 2012). HY5 and the related HY5-HOMOLOGY (HYH) proteins interact directly with a T/G-box cis-acting element within the HY5 promoter, activating its transcription in response to visible light and UV-B (Binkert et al., 2014). It was reported very recently that the primary activity of HY5 is to promote transcription and that this function relies on other, likely light-regulated, factors (Bischof, 2020; Burko et al., 2020).

COLD-REGULATED GENE27 (COR27) and COR28 were identified as cold-responsive genes in Arabidopsis transcriptome profiling studies (Fowler and Thomashow, 2002; Mikkelsen and Thomashow, 2009). The expression of COR27 and COR28 is regulated by both low temperatures and light, and represents a trade-off between flowering and freezing tolerance, as the cor27 and cor28 mutants show delayed flowering and increased resistance to cold stress (Li et al., 2016). Furthermore, COR27 and COR28 are involved in regulating the period length of the circadian clock and associate with the chromatin regions surrounding the clock genes PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR5 (PRR5) and TIMING OF CAB2 EXPRESSION1 (TOC1) to regulate their transcription (Li et al., 2016). Here, we show that COR27 and COR28 physically interact with COP1 and undergo COP1-mediated degradation in the dark. COR27 and COR28 negatively regulate photomorphogenesis by repressing the transcriptional activity of HY5, thereby fine-tuning the COP1-to-HY5 regulatory hub to ensure proper photomorphogenic development in the light. COR27, COR28, and HY5 are all degraded in the dark, and COR27 inhibits the transcriptional activity of HY5 even in the dark to promote skotomorphogenic growth.

RESULTS

COR27 and COR28 Physically Interact with COP1

We previously showed that COR27 and COR28 protein levels were low in plants kept in the dark (Li et al., 2016). Here, we used transgenic lines overexpressing COR27 fused to the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) from the construct 35S:YFP-COR27 and determined that COR27 protein levels increased significantly within 1 h of a white-light treatment or 2 h of a blue-light treatment (Supplemental Figures 1A to 1D). Furthermore, COR27 was highly expressed in seedlings pretreated with blue light, but COR27 protein levels decreased markedly within 3 h after the seedlings were transferred from white or blue light to darkness (Supplemental Figures 1A to 1D).We next examined the effects of blue light on the levels of the COR27 protein in the presence or absence of the 26S proteasome inhibitor MG132. The abundance of COR27 decreased markedly in darkness in the absence of MG132; by contrast, COR27 levels remained constant in darkness in the presence of MG132 (Supplemental Figures 1E and 1H), suggesting that the decrease of COR27 protein in the absence of blue light is due to its proteolysis by the 26S proteasome. The increase in COR27 in response to blue light and its decrease in the absence of blue light in the cry1 cry2 double mutant were not as pronounced as in the wild type (Supplemental Figures 1I to 1L). Therefore, the CRY1 and CRY2 photoreceptors at least partially mediate the blue-light suppression of COR27 degradation.

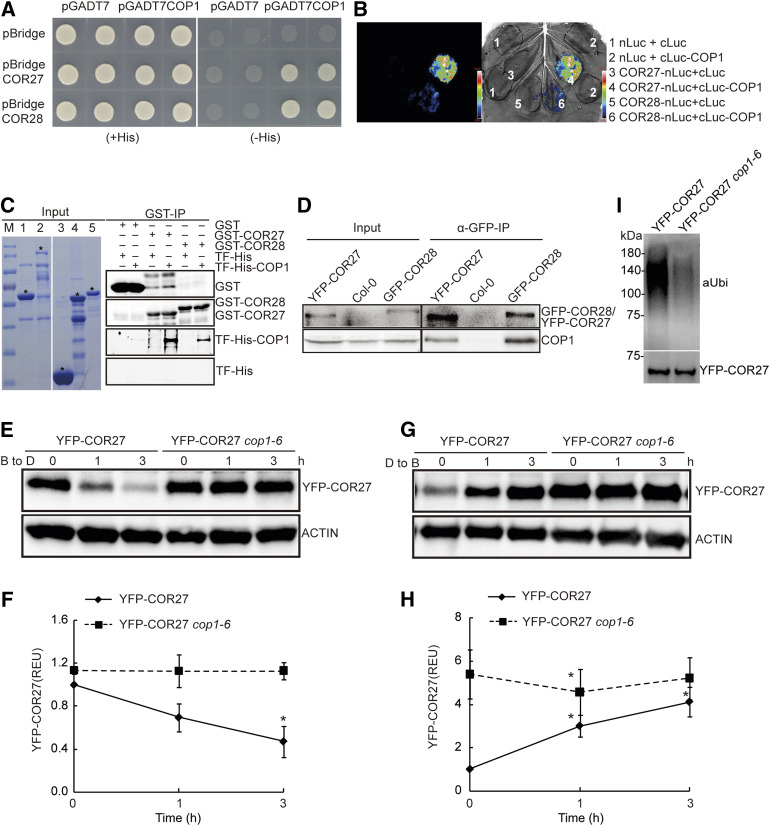

To elucidate the mechanism by which blue light stabilizes the COR27 and COR28 proteins, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen on an Arabidopsis cDNA library to identify COR27- and COR28-interacting proteins. We identified COP1 and SPA1 (a COP1-interacting protein) in screens using COR27 or COR28, respectively, as the bait. The full list of identified COR27 and COR28 interactors is shown in Supplemental Table 1. In yeast cells, both COR27 and COR28 interacted with COP1 (Figure 1A). Bimolecular luminescence complementation (BiLC) assays also indicated that COP1 interacts with COR27 and COR28 in plant cells. Indeed, we detected strong luciferase activity in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves co-infiltrated with cLUC-COP1 and COR27-nLUC or COR28-nLUC plasmids (Figure 1B). We also used an in vitro pulldown assay to test the interaction between COP1 and COR27 or COR28 produced and purified from Escherichia coli. Both COR27 and COR28 pulled down COP1 in this assay (Figure 1C), further indicating that they physically interact in vitro. We performed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) analyses in transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings expressing YFP or GFP-tagged COR27 or COR28. COP1 co-precipitated with COR27 or COR28 (Figure 1D). These results indicate that COR27 and COR28 interact with COP1 in planta.

Figure 1.

COR27 and COR28 Interact with COP1.

(A) His auxotrophy assays showing the interaction between COR27 or COR28 and COP1. Yeast cells (strain AH109) containing plasmids encoding the indicated proteins were grown on medium in the presence (+) or absence (–) of His in the dark for 3 d.

(B) BiLC assays showing COR27 and COR28 interacting with COP1. Leaf epidermal cells of N. benthamiana were co-infiltrated with nLuc, COR27-nLuc, or COR28-nLuc and cLuc, or cLuc-COP1, as indicated.

(C) In vitro pulldown assays showing the interaction of COR27 or COR28 with COP1. GST or GST-tagged COR27 or COR28 bound to glutathione-agarose beads was mixed with His-TF or His-TF-COP1 purified from E. coli, as shown in the Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel (left): M, size marker, (1) His-TF tag, (2) His-TF-tagged COP1, (3) GST tag, (4) GST-tagged COR27, and (5) GST-tagged COR28. The asterisk indicates the respective target protein. The pulldown products were analyzed using immunoblots probed with anti-GST or anti-TF antibodies (right).

(D) Co-IP assays showing in vivo protein interactions. Proteins were extracted from 10-d–old SD-grown YFP-COR27, GFP-COR28, or Col-0 seedlings. Input: Immunoblots showing the level of YFP-COR27, GFP-COR28, and COP1 in total protein extracts. α-GFP-IP: Immunoprecipitation products precipitated with anti-GFP antibody. Total proteins (input) or immunoprecipitation products were probed in immunoblots using antibodies against GFP or COP1.

(E) Immunoblots showing that the cop1-6 mutation blocks the degradation of COR27 in the dark. B to D, range of blue light to darkness.

(F) Quantified protein levels in (E) with three biological repeats are shown. The relative level of YFP-COR27 accumulation as presented in relative expression units (REUs) is calculated based on the formula (YFP-COR27t/ACTINt)/(YFP-COR27°/ACTIN0 in YFP-COR27 [in Col-0]) in which “YFP-COR27” and “ACTIN” denote the digitized band intensities of YFP-COR27 or ACTIN in the respective samples collected at time 0 or at the indicated time (T) after dark treatment. Error bars represent sd (n = 3). Asterisks indicate a significant difference compared with the protein level at time 0 (*P < 0.05; paired samples t test).

(G) Immunoblots showing a lack of light-induced COR27 accumulation in cop1-6 mutant seedlings. D to B, range of darkness to blue light.

(H) Quantified protein levels in (G) are shown. The relative level of YFP-COR27 accumulation as presented in relative expression units (REUs) is calculated by the formula (YFP-COR27t/ACTINt)/(YFP-COR27°/ACTIN0 in YFP-COR27 [in Col-0]), in which “YFP-COR27” and “ACTIN” denote the digitized band intensities of YFP-COR27 or ACTIN in the respective samples collected at time 0 or at the indicated time (T) after blue-light exposure. Error bars represent sd (n = 3). Asterisks indicate a significant difference compared with the protein level at time 0 (*P < 0.05; paired samples t test).

(I) SD-grown 10-d–old YFP-COR27 (in Col-0) and YFP-COR27 cop1-6 transgenic lines were treated with 50 μM of MG132 (26S proteasome inhibitor) at ZT7.5, then moved into darkness at ZT8 for 4 h.YFP-COR27 protein was extracted by immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP-conjugated sepharose, and separated on a pre-poured gradient gel. The ubiquitinated COR27 molecules between 75 kD and 180 kD in size were detected using an anti-ubiquitin antibody (αUbi). Anti-GFP antibody was used to detect non-ubiquitinated YFP-COR27 to ensure equal loading.

COP1 Is Responsible for the Degradation of COR27 Protein in the Dark

COP1 physically interacts with COR27 and COR28. COR27 is degraded in a 26S proteasome–dependent pathway in the absence of blue light; therefore, we hypothesized that COR27 might also be a substrate for COP1, and that COP1 may be responsible for the ubiquitination and degradation of COR27 in darkness. To explore this hypothesis, we first analyzed the protein stability of COR27 in the cop1-6 mutant. COR27 protein levels (as reported by YFP) increased in response to blue light and decreased in the absence of blue light in the Columbia-0 (Col-0) but not in the cop1-6 background (Figures 1E to 1H). Therefore, COP1 is responsible for the degradation of COR27 in the absence of blue light. Furthermore, COR27 showed high levels of ubiquitination in Col-0, but much reduced ubiquitination levels in cop1-6 (Figure 1I). These results indicate that COP1 is responsible for the degradation of COR27 in the absence of light. CRY1 and CRY2 might regulate the protein stability of COR27 by repressing COP1, consistent with the finding that we observed no significant differences in COR27 protein levels between the cry1 cry2 double mutant and Col-0 (Supplemental Figures 1I to 1L).

COR27 and COR28 Promote Hypocotyl Elongation

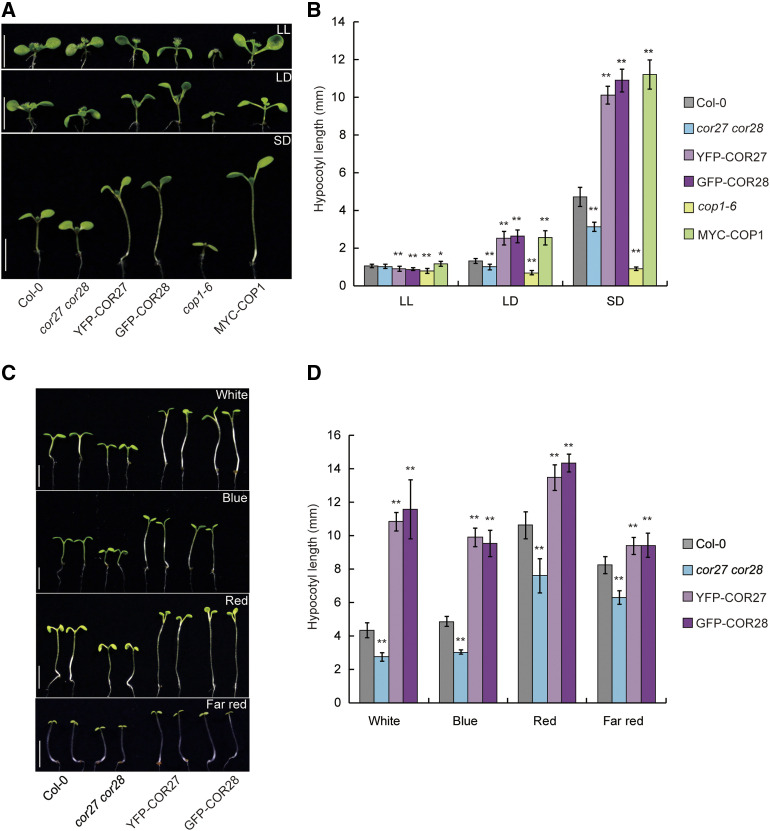

To investigate whether COR27 and COR28 might play a role in regulating photomorphogenesis, we grew Col-0, cor27, cor28, cor27 cor28, and transgenic seedlings overexpressing COR27 or COR28 in constant white light, long-day (LD) conditions, short-day (SD) conditions, or in darkness. The cor27 cor28 double mutant seedlings exhibited a dramatic short hypocotyl phenotype in both LD and SD conditions compared with Col-0, but not in darkness or in constant light (Figures 2A and 2B; Supplemental Figures 2A and 2B). The hypocotyl lengths of cor27 and cor28 single mutant seedlings were slightly shorter than those of Col-0 in SD conditions (Supplemental Figures 2C and 2D), consistent with the partial redundancy of COR27 and COR28 in the regulation of photomorphogenesis. The COR27- and COR28-overexpression lines showed longer hypocotyls than Col-0 under both LD and SD conditions, but not in constant darkness or in constant light (Figure 2A and 2B; Supplemental Figures 1A, 2B, and 2E). All genotypes tested (Col-0, cor27 cor28, and transgenic lines overexpressing COR27 or COR28) showed similar hypocotyl lengths when grown in constant darkness; therefore, we next grew them in SD conditions with white, blue, red, and far-red light for 7 d to analyze which aspect of light regulated hypocotyl growth. The cor27 cor28 double mutant seedlings developed shorter hypocotyls than Col-0 when grown under blue, red, or far-red light in SD conditions, whereas the overexpression lines produced significantly longer hypocotyls, similar to their respective patterns under white light (Figures 2C and 2D). These results indicate that COR27 and COR28 promote hypocotyl elongation and act as negative regulators of the blue-, red-, and far-red light–mediated repression of hypocotyl elongation.

Figure 2.

COR27 and COR28 Promote Hypocotyl Elongation.

(A) Phenotypes of 7-d–old Col-0, cor27 cor28, 35S:YFP-COR27 (YFP-COR27), 35S:GFP-COR28 (GFP-COR28), 35S:MYC-COP1 (MYC-COP1), and cop1-6 seedlings grown in constant white light (LL), LD (16 h/8 h), and SD (8 h/16 h) conditions. Scale bars = 5 mm.

(B) Quantification of hypocotyl lengths of the genotypes indicated in (A). Error bars represent sd (n = 15). Asterisks indicate a significant difference compared with the wild type under the same treatment conditions (*P < 0.05; **I < 0.01, paired samples t test).

(C) Phenotypes of 7-d–old Col-0, cor27 cor28, YFP-COR27, GFP-COR28, cop1-6, and MYC-COP1 seedlings grown under SD conditions with white (90 μmol/m2/s), blue (40 μmol/m2/s), or red light (40 μmol/m2/s), or far-red light (8 μmol/m2/s). Scale bars = 5 mm.

(D) Quantification of hypocotyl lengths indicated in (C). Error bars represent sd (n = 15). Asterisks indicate a significant difference compared with the wild type under the same treatment conditions (**P < 0.01 paired samples t test).

COR27 and COR28 Regulate the Expression of COP1-Regulated Genes

To elucidate the mechanism by which COR27 and COR28 regulate photomorphogenesis, we performed RT-qPCR to analyze the expression of HY5 and PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE1 (PRE1) in LD-grown Col-0 and cor27 cor28 seedlings. HY5 loss of function leads to dramatically elongated hypocotyls under all light conditions (Ang et al., 1998), while PRE1 was reported to regulate cell elongation (Lee et al., 2006). HY5 transcript levels were higher in the cor27 cor28 double mutant relative to Col-0, especially at night, while PRE1 mRNA levels were lower in cor27 cor28 compared with Col-0 during both the morning and night (Supplemental Figures 2F and 2G).

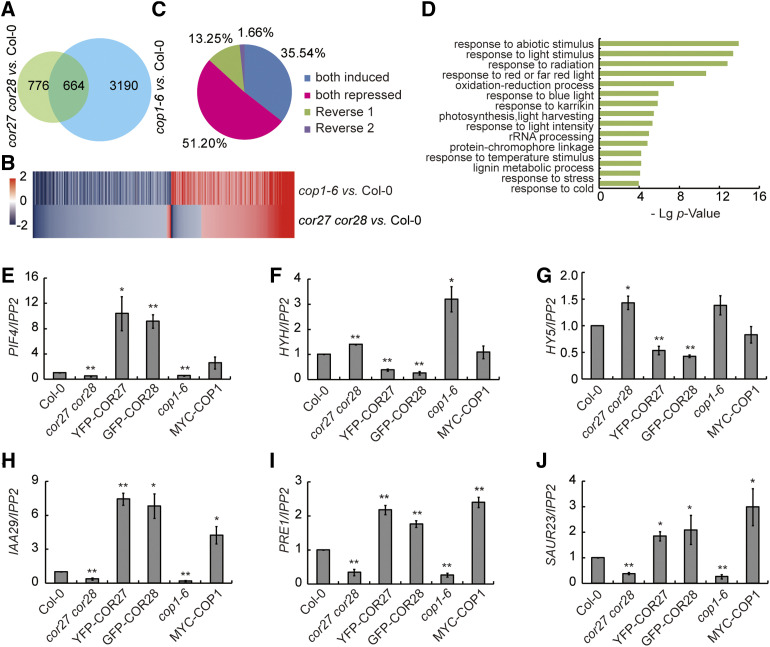

We then performed deep sequencing of the transcriptome (RNA sequencing [RNA-seq]) to identify downstream genes affected in the cor27 cor28 double mutant at night when grown in SD conditions. We collected samples at Zeitgeber Time (ZT) 20, that is 12 h after lights off, late into the dark period. We identified 1,440 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between cor27 cor28 and Col-0 (Figure 3A; Supplemental Data Set 1). As shown above, COP1 is responsible for the degradation of COR27 in darkness, and COR27 is involved in photomorphogenesis. COR27 should therefore influence the expression of genes downstream of COP1. Indeed, our RNA-seq data sets of the genes differentially expressed in cor27 cor28 significantly overlapped with RNA-seq data sets of genes differentially expressed in the cop1-6 mutant (Figures 3A to 3D; Supplemental Data Set 2). For 87% of these genes, the effects of the cor27 cor28 double mutant on gene expression were the same as in cop1-6 (compared with cor27 cor28 versus Col-0 and cop1-6 versus Col-0 in Figures 3B and 3C). These results indicate that COP1, COR27, and COR28 exert similar effects on many commonly regulated genes. A gene-ontology (GO) analysis revealed a marked enrichment in light-responsive, growth-related functions in the cop1-6 and cor27 cor28 co-regulated genes, including PIF4 and HYH (Figure 3D). These genomic data thus provide direct evidence for the important roles of COR27 and COR28 in photomorphogenesis, particularly in their regulation of genes involved in cell elongation.

Figure 3.

Genome-Wide Transcriptomic Analysis of Genes Co-regulated by COR27, COR28, and COP1.

(A) Venn diagram showing the overlap between the sets of DEGs in Col-0 versus cor27 cor28 and Col-0 versus cop1-6.

(B) Heatmap of COR27-, COR28-, and COP1-regulated genes. Scale bar = fold changes (log2 value).

(C) Distribution of genes co-regulated by COR27, COR28, and COP1. Reverse 1: COP1-repressed and COR27- and COR28-induced gene. Reverse 2: COP1-induced and COR27 and COR28-repressed gene.

(D) GO analysis of the co-regulated genes in (B).

(E to J) COR27, COR28, and COP1 co-regulate the expression of the cell elongation genes PIF4, HYH, HY5, PRE1, IAA29, and SAUR23. RT-qPCR analysis of gene expression of 7-d–old Col-0, cor27 cor28, 35S:YFP-COR27 (YFP-COR27), 35S:GFP-COR28 (GFP-COR28), cop1-6, and 35S:MYC-COP1 (MYC-COP1) seedlings grown in SD conditions. Samples were collected at ZT20. The IPP2 gene was used as internal control. Gene expression in different genotypes were normalized to Col-0 (gene/IPP2 in Col-0 was set to 1). Error bars represent sd of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate a significant difference compared with Col-0 (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, paired samples t test).

We verified the transcriptomic data using RT-qPCR. We selected PIF4, HYH, PRE1, INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID INDUCIBLE19 (IAA29), and ARABIDOPSIS COLUMBIA SAUR GENE23 (SAUR23) from the list of genes commonly regulated by COR27, COR28, and COP1 (Figures 3E to 3J). HY5 and its homologue HYH were both upregulated in cor27 cor28 and cop1-6 mutants, but downregulated in the transgenic lines overexpressing COR27 or COR28. Conversely, PIF4, PRE1, IAA29, and SAUR23 were all upregulated in seedlings overexpressing COR27, COR28, or COP1 compared with Col-0, but downregulated in the cor27 cor28 and cop1-6 mutants.

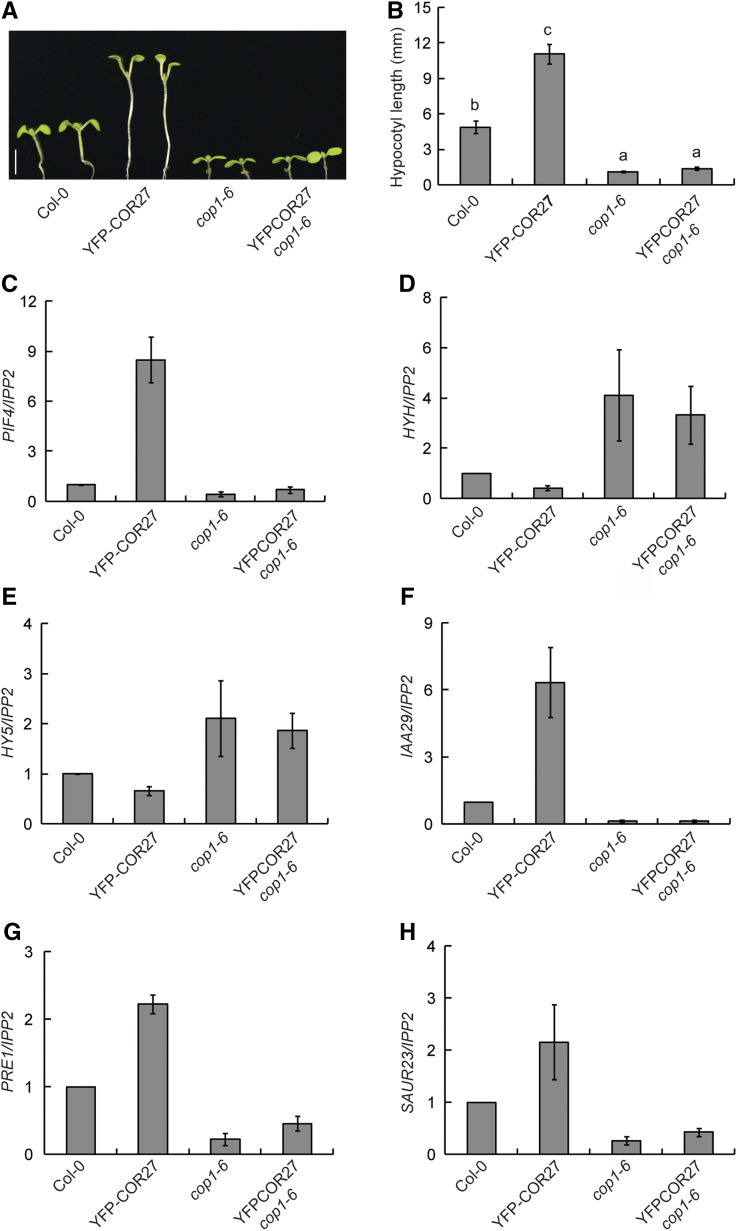

COR27 and COR28 Promote Hypocotyl Elongation in a COP1-Dependent Manner

To further determine the relationship between COP1 and COR27, we investigated the genetic interactions between the COR27 and COP1 loci. We crossed the 35S:YFP-COR27 transgenic line with the cop1-6 mutant, resulting in the YFP-COR27 cop1-6 line. The long-hypocotyl phenotype of seedlings overexpressing YFP-COR27 was mostly suppressed in the cop1-6 background (Figures 4A and 4B), which suggested that COR27-promoted hypocotyl elongation is dependent on COP1. The hypocotyl phenotype of GFP-COR28 cop1-6 was also similar to that of cop1-6 (Supplemental Figures 3A and 3B). Consistent with these observations, HYH and HY5 transcript levels were markedly higher in YFP-COR27 cop1-6 seedlings than in YFP-COR27 in the Col-0 background, while the transcript levels of PIF4, IAA29, PRE1, and SAUR23 were significantly lower in YFP-COR27 cop1-6 seedlings than in YFP-COR27 in the Col-0 background (Figures 4C to 4H). These results indicate that COR27 regulates the transcription of these elongation-related genes in a COP1-dependent manner.

Figure 4.

COR27 Inhibits Photomorphogenesis in a COP1-Dependent Manner.

(A) Phenotypes of 7-d–old Col-0, 35S:YFP-COR27 (YFP-COR27), cop1-6, and YFP-COR27 cop1-6 seedlings grown in SD conditions. Scale bars = 5 mm.

(B) Quantification of hypocotyl lengths of the genotypes indicated in (A). Error bars represent sd (n = 15). The letters “a” to “c” indicate statistically significant differences between the indicated genotypes, as determined by Turkey’s Honest Significant Difference test (P < 0.05).

(C) to (H) The function of COR27 in regulating elongation-related gene expression depends on COP1. RT-qPCR analysis of gene expression of 7-d–old Col-0, YFP-COR27, cop1-6, and YFP-COR27 cop1-6 seedlings grown in SD conditions at ZT20. The IPP2 gene was used as internal control. Gene expression in different genotypes was normalized to Col-0 (gene/IPP2 in Col-0 was set to 1). Error bars represent sd of three biological replicates.

COR27 Physically Interacts with HY5

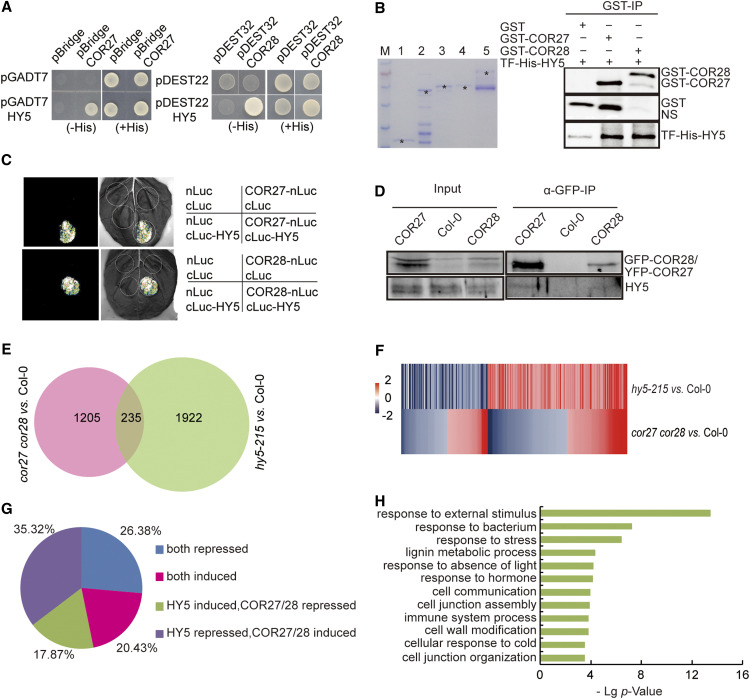

COR27 and COR28 indirectly bind to the chromatin surrounding PRR5 and TOC1 to repress their expression and regulate the circadian clock (Li et al., 2016). We previously proposed that COR27 and COR28 might form a protein complex with other transcription factors to associate with the chromatin at these regions (Li et al., 2016). To determine the mechanism by which COR27 and COR28 regulate photomorphogenesis and the expression of downstream elongation-related genes, we tested the interaction between COR27, COR28, and various proteins known to be involved in regulating hypocotyl elongation using a yeast two-hybrid assay. Among the 32 proteins we tested (gene names and accession numbers are given in Supplemental Table 2), HY5 interacted with COR27 and COR28 in yeast cells (Figure 5A). We also pulled down HY5 with both COR27 and COR28 in an in vitro pull-down assay (Figure 5B), indicating that the proteins physically interact in vitro. We further confirmed the interaction between HY5 and COR27 and COR28 in plant cells by BiLC assay. Indeed, we detected strong luciferase activity in N. benthamiana leaves co-infiltrated with cLUC-HY5 and COR27-nLUC or COR28-nLUC plasmids (Figure 5C). Finally, we performed co-IP analyses in transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings expressing YFP-tagged COR27 and GFP-tagged COR28 in the Col-0 background, which revealed that HY5 co-precipitated with COR27 and COR28 (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

COR27 and COR28 Interact with HY5 to Regulate the Expression of Various Genes.

(A) His auxotrophy assays showing the interaction between COR27 or COR28 and HY5. Yeast cells (strain AH109) containing plasmids encoding the indicated proteins were grown on medium in the presence (+) or absence (–) of His in the dark for 3 d.

(B) In vitro pulldown assays showing that COR27 and COR28 interact with HY5. GST or GST-tagged COR27 or COR28 bound to glutathione-agarose beads were mixed with His-TF or His-TF-HY5 purified from E. coli, as shown on the Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel (left): M, marker; (1) GST tag, (2) GST-tagged COR27, (3) GST-tagged COR28, (4) His-TF tag, and (5) His-TF-tagged HY5. The pulldown products were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-GST or anti-HY5 antibodies (right). NS, non-specific band.

(C) BiLC assays showing that COR27 and COR28 interact with HY5. Leaf epidermal cells of N. benthamiana were co-infiltrated with nLuc, COR27-nLuc, or COR28-nLuc and cLuc, or cLuc-HY5, as indicated.

(D) Co-IP assays showing that COR27 and COR28 interact with HY5 in vivo. Ten-d–old SD-grown YFP-COR27, GFP-COR28, or Col-0 seedlings were collected and treated with MG132 (50 μM) at ZT8, then moved to the dark for 4 h, after which the proteins were extracted for co-IP. Input: Immunoblots showing the level of YFP-COR27, GFP-COR28, or HY5 in total protein extracts. α-GFP-IP: Immunoprecipitation products precipitated using anti-GFP antibody. Total proteins (input) or immunoprecipitation products were probed in immunoblots with antibodies against GFP or HY5.

(E) Venn diagram showing the overlap between the sets of DEGs in Col-0 versus cor27 cor28 and Col-0 versus hy5-215.

(F) Heatmap of COR27 and COR28 and HY5-regulated genes. The scale bar shows fold changes (log2 value).

(G) Distribution of genes co-regulated by COR27, COR28, and HY5.

(H) GO analysis of the co-regulated genes indicated in (F).

COR27 and COR28 Influence the Expression of HY5-Regulated Genes

COR27 physically interacts with HY5, suggesting they may act together to regulate transcription and photomorphogenesis. To explore how COR27 and COR28 might influence the expression of HY5-target genes, we performed RNA-seq to identify downstream genes affected in the hy5-215 mutant at night (SD, ZT20). Our RNA-seq data sets of differentially expressed gene (DEGs) in cor27 cor28 relative to Col-0 significantly overlapped with RNA-seq data sets of DEGs in hy5-215 (Figures 5E to 5G, Supplemental Dataset 3). There were 235 genes co-regulated by both COR27 and COR28 and HY5. For 53.2% of these genes, the cor27 cor28 double mutant had the opposite effect from that in hy5, with 17.9% promoted by HY5 but repressed by COR27 and COR28, including HYH and ELF4; the remaining 35.3% were repressed by HY5 but promoted by COR27 and COR28, including PIF4, IAA29, and SAUR23. These results indicated that COR27, COR28, and HY5 act in an opposite manner on the regulation of a large number of common genes. At the same time, we compared the list of COR27- and COR28-regulated genes with the genes whose promoters are bound by HY5, previously identified by Lee et al. (2006; Figure 5D): 20% of the genes affected by the loss of COR27 and COR28 were direct targets of HY5 (Supplemental Figures 4E and 4F). Collectively, these results indicate that HY5 and COR27 and COR28 regulate a large number of common genes. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis showed that the molecular function categories “stimulus” and “absence of light response” genes were markedly changed in the list of genes commonly regulated by COR27, COR28, and HY5, including HYH and PIF4 (Figure 5H; Supplemental Figure 4F). These genomic data thus provide direct evidence for the important role of COR27 in HY5-mediated regulation of gene expression.

Similarly, HY5 and PIFs co-regulated photomorphogenesis in both LD and SD conditions. When we grew Col-0, hy5-215, and pifq (a quadruple pif mutant) seedlings in LD and SD conditions, pifq exhibited a dramatically short hypocotyl phenotype relative to the wild type, and in sharp contrast to the long hypocotyl phenotype displayed by hy5-215 (Supplemental Figures 4A to 4C). Consistent with these phenotypes, PRE1 and IAA29 transcript levels were higher in hy5-215 compared with Col-0, but lower in pifq seedlings. HY5 also affects PIF4 expression, and hy5-215 caused the upregulation of PIF4 (Supplemental Figure 4D).

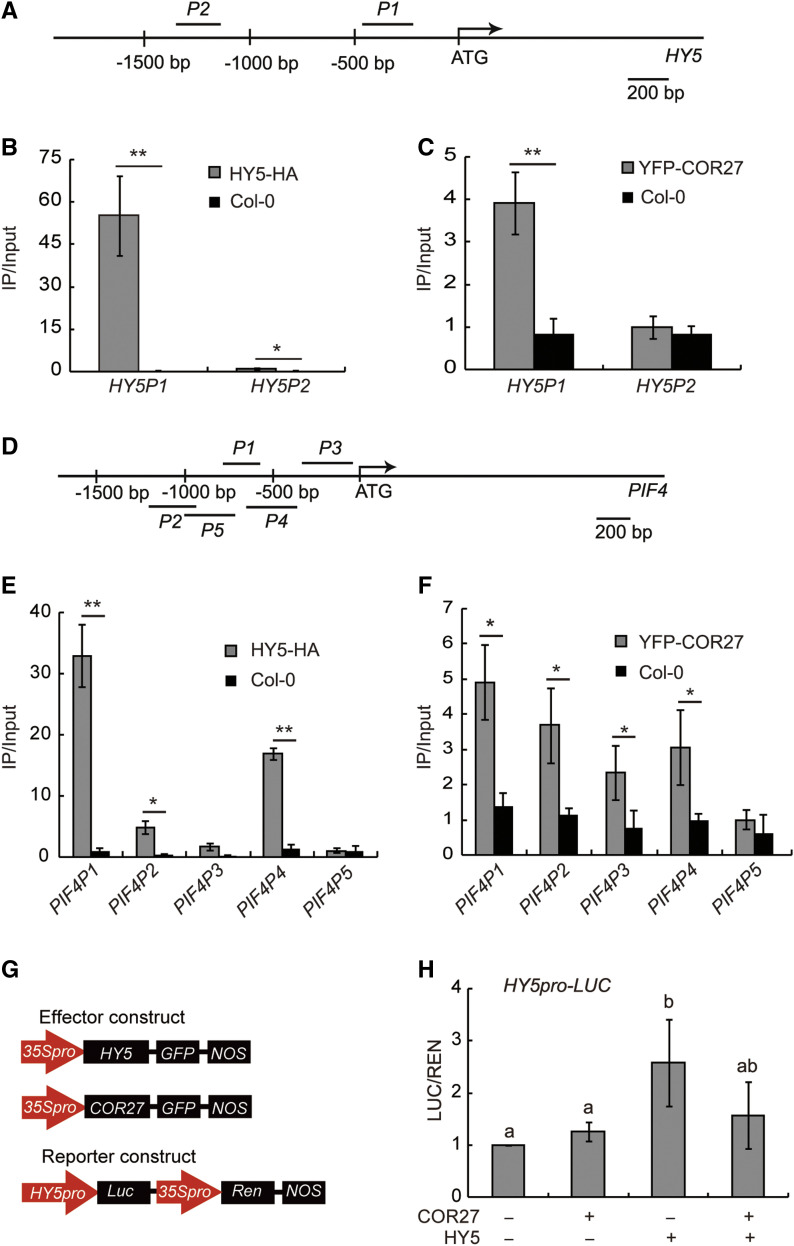

COR27 Associates with the Promoters of HY5 Targets to Regulate their Expression

COR27 physically interacts with HY5 and regulates the expression of HY5-target genes. To achieve this role, we hypothesized that COR27 might physically associate with the same genomic regions to which HY5 binds. To test this hypothesis, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR assays, which revealed that COR27 did associate with the same chromatin region of the HY5 and PIF4 promoters as HY5 does in vivo (Figures 6A to 6F). We used the same PCR primer pairs to detect chromatin binding by HY5 and COR27. A yeast one-hybrid assay revealed that HY5, but not COR27, bound to the PIF4 promoter (Supplemental Figures 5A and 5B), indicating that COR27 physically interacts with HY5 to then associate with the genomic regions to which HY5 binds.

Figure 6.

COR27 Associates with HY5 to Regulate Gene Expression During Photomorphogenesis.

(A) Diagram depicting the HY5 promoter, including the two promoter sites studied (P1 and P2).

(B) and (C) ChIP-qPCR results showing that (B) HY5-HA and (C) YFP-COR27 bind to the HY5 promoter. The P1 region contains various binding sites of the HY5 promoter, including the ACG box, T/G box, and E box. The error bars represent sd of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in the comparisons shown (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, paired samples t test)

(D) Diagram depicting the PIF4 promoter, including the five promoter sites studied (P1 to P5).

(E and F) ChIP-qPCR results showing that (E) HY5-HA and (F) YFP-COR27 bind to the PIF4 promoter. The error bars represent sd of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate a significant difference compared in the comparisons shown (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, paired samples t test).

(G) Structure of the HY5 promoter-driven dual-luciferase (Luc) reporter gene and two effector genes (35S:COR27-GFP, 35S:HY5-GFP). For the reporter constructs: 35S promoter, HY5 promoter (–700 bp to –1 bp); Ren and Luc are indicated.

(H) Arabidopsis protoplasts isolated from the hy5-215 mutant were transfected with reporter DNA together with empty effector DNA (GFP), COR27, HY5, or COR27+HY5. After transfection, the protoplasts were kept in low light for 12 h. Luciferase activity was normalized to REN activity. Error bars represent the sd of three biological replicates. Letters “a” and “b” indicate statistically significant differences for the indicated values, as determined by a one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test (P < 0.05).

We then analyzed whether COR27 affected the transcriptional activity of HY5 on its target promoters using a transient transcription assay in Arabidopsis protoplasts and N. benthamiana. We used a dual-luciferase reporter plasmid encoding the firefly luciferase (LUC) gene driven by the HY5 or PIF4 promoter and a Renilla luciferase (REN) gene driven by the constitutive cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter (Figure 6G; Supplemental Figure 5C). We transiently expressed the HY5pro:LUC reporter in hy5-215 protoplasts together with either 35S:HY5-GFP or 35S:COR27-GFP or both. The luciferase activity level from the HY5pro-LUC reporter was ∼2.5-fold higher when we co-expressed HY5 in the protoplasts relative to co-expressed GFP, while the combination of HY5 and COR27 induced the reporter very modestly (Figure 6H). We also infiltrated N. benthamiana leaves with an Agrobacterium strain containing the reporter construct (pGreen-PIF4pro:LUC) alone or mixed with an Agrobacterium strain containing the indicated effector plasmid (pCambia1300-HY5-YFP, pEGAD-MYC-COR27, or pCambia1306-VP16-HY5-Flag). We fused HY5 to the VP16 activation domain (from Herpes simplex virus protein vmw65) to make it a strong constitutive activator of PIF4 transcription rather than its typical function as a repressor (Supplemental Figure 4D), allowing us to more easily analyze the effect of COR27 on HY5 transcriptional activity. COR27 repressed the transcriptional activity of VP16-HY5 on the PIF4pro:LUC reporter gene (Supplemental Figure 5D). COR27 itself did not significantly affect the transcription of PIF4pro:LUC or HY5pro:LUC (Figure 6H; Supplemental Figure 5D); however, it did inhibit the transcriptional activity of HY5.

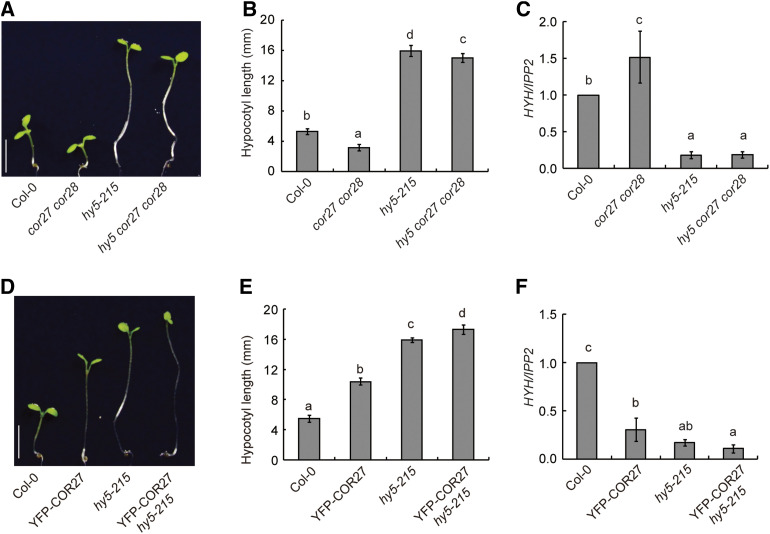

To further study the relationship among COR27, COR28, and HY5, we investigated the genetic interactions between the corresponding genes. We crossed the cor27 cor28 double mutant to hy5-215, to generate the hy5 cor27 cor28 triple mutant (Supplemental Figure 6A). Bringing the hy5-215 mutation into the cor27 cor28 double mutant background dramatically suppressed its short hypocotyl phenotype, resulting in hypocotyls that were almost as long in the triple mutant as in the hy5-215 single mutant (Figures 7A and 7B). Transcript levels of HYH were also markedly lower in hy5 cor27 cor28 compared with cor27 cor28, and were similar to those seen in hy5-215 (Figure 7C), indicating that COR27 and COR28 regulate hypocotyl elongation at least partially via HY5, and that COR27 and COR28 also regulate hypocotyl growth through HY5-independent pathways. Consistent with this, YFP-COR27 hy5-215 showed longer hypocotyls than YFP-COR27 in the Col-0 background, and slightly longer hypocotyls than in the hy5-215 mutant. HYH transcript levels were also lower in YFP-COR27 hy5-215 seedlings than in YFP-COR27 seedlings, and comparable to those seen in hy5-215, indicating that COR27 and COR28 regulate the transcription of HYH through HY5 (Figures 7D to 7F).

Figure 7.

COR27 and COR28 Interact with HY5 to Regulate Gene Expression and Photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis.

(A) Phenotypes of 7-d–old Col-0, cor27 cor28, hy5-215, and hy5-215 cor27 cor28 seedlings grown in SD conditions. Scale bars = 5 mm.

(B) Quantification of hypocotyl lengths of Col-0, cor27 cor28, hy5-215, and hy5-215 cor27 cor28. Seven-d–old seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown in SD conditions. Error bars represent the sd (n = 25). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between the indicated genotypes, as determined using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test (P < 0.05).

(C) RT-qPCR analysis of HYH expression of 7-d–old Col-0, cor27 cor28, hy5-215, and hy5-215 cor27 cor28 seedlings grown in SD conditions and collected at ZT20. The IPP2 gene was used as internal control. HYH expression in different genotypes was normalized to Col-0 (gene/IPP2 in Col-0 was set to 1). Error bars represent the sd of three biological replicates. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between the indicated genotypes, as determined using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test (P < 0.05).

(D) Phenotypes of 7-d–old Col-0, YFP-COR27, hy5-215, and YFP-COR27 hy5-215 seedlings grown in SD conditions. Scale bars = 5 mm.

(E) Quantification of hypocotyl lengths of Col-0, YFP-COR27, hy5-215, and YFP-COR27 hy5-215. Seven-d–old seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown in SD conditions. Error bars represent the sd (n = 25). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between the indicated genotypes, as determined using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test (P < 0.05).

(F) RT-qPCR analysis of HYH expression of 7-d–old Col-0, YFP-COR27, hy5-215, and YFP-COR27 hy5-215 plants grown in SD conditions and collected at ZT20. The IPP2 gene was used as internal control. Error bars represent the sd of three biological replicates. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between the indicated genotypes, as determined using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Dark growth (skotomorphogenesis) and light-mediated growth (photomorphogenesis) are critical for germination and seedling development. Buried seeds use elongated hypocotyls, closed cotyledons, and curved apical hooks (skotomorphogenic growth) to limit mechanical damage after germination as they grow through soil particles, until they reach the soil surface. Once top-side, seedlings are exposed to light, which then inhibits hypocotyl elongation and promotes cotyledon expansion (photomorphogenesis). COP1 is a central repressor of light signaling, acting downstream of multiple photoreceptors (Ang and Deng, 1994; Christie et al., 2012). COP1 negatively regulates photomorphogenesis by mediating the degradation of various photomorphogenesis-promoting transcription factors in the dark, including HY5 (Yi and Deng, 2005; Jiao et al., 2007; Foreman et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011). Light represses COP1 by activating multiple photoreceptors, stabilizing the HY5 protein (Ang and Deng, 1994; Christie et al., 2012). The COP1–HY5 module plays a critical role in regulating photomorphogenesis. COR27 and COR28 were identified as cold-responsive genes during Arabidopsis transcriptome analysis, and the expression of COR27 was shown to be clock- and light-regulated (Fowler and Thomashow, 2002; Mikkelsen and Thomashow, 2009; Li et al., 2016). Light- and low-temperature–regulated COR27 and COR28 are involved in the regulation of the circadian clock, freezing tolerance, and flowering time, representing a trade-off between flowering and freezing tolerance (Li et al., 2016).

Here, we showed that COR27 and COR28 are novel regulators of photomorphogenesis and are involved in the COP1–HY5-mediated elongation of Arabidopsis seedlings in response to light. Like the HY5 protein, COR27 and COR28 are degraded in the dark via the 26S proteasome pathway. We also showed that COP1 physically interacts with COR27 and COR28, that it is responsible for their degradation, and that their protein levels are relatively low in etiolated seedlings. Light promotes the accumulation of HY5, COR27, and COR28, most likely due to the light-mediated inactivation of COP1 (Ang and Deng, 1994; Christie et al., 2012). COP1 regulates the protein stability of HY5, COR27, and COR28, while COR27 or COR28 form a protein complex with HY5 on the chromatin of HY5 target genes to modulate their transcription and ultimately photomorphogenesis. COR27 inhibits the transcriptional activity of HY5 even in the dark to promote skotomorphogenic growth, and COR27 and COR28 fine-tune photomorphogenesis by modulating the COP1–HY5 module in response to changing light environments (Figure 6F).

Multiple HY5-interacting proteins have been identified and characterized, such as HYH, G-BOX BINDING FACTOR1, CALMODULIN7, B-BOX DOMAIN PROTEIN21 (BBX21), BBX22, BBX24, BBX25, BBX28, and BBX32. These factors interact with HY5 to positively or negatively regulate its transcriptional activity (Holm et al., 2002; Datta et al., 2006, 2008; Holtan et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2012; Gangappa et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018). HY5 is a key transcription factor in photomorphogenesis, functioning alongside multiple factors to fine-tune HY5 biochemical activity and gene expression in response to the changing light environment. COP1 also regulates the protein stability of BBX28, which represses photomorphogenesis by inhibiting the DNA binding activity of HY5 (Lin et al., 2018). Different proteins thus regulate HY5 via different mechanisms, with some regulating its DNA binding activity while others form complexes with HY5 at its target chromatin sites to regulate its transcriptional activity. The expression of COR27 and COR28 is also regulated by cold temperatures and the circadian clock; they may integrate multiple signals to fine-tune skotomorphogenesis and photomorphogenesis. The transcriptome data indicates that cold-responsive genes are enriched in the COP1, HY5, COR27, and COR28 co-regulated genes, suggesting that these proteins may also be involved in the joint regulation of cold tolerance.

COR27 and COR28 are both small proteins with unknown biochemical functions. They do not have any known DNA binding domains, and cannot bind DNA themselves in vitro, indicating that they are unlikely to be transcription factors (Supplemental Figures 5A and 5B). We previously showed that they physically associate with the genomic regions of the clock genes TOC1 and PRR5 to directly regulate their transcription, and hypothesized that they may form a protein complex with other DNA binding transcription factors to associate with chromatin and regulate the transcription of these and other clock genes (Li et al., 2016). Here, we showed that COR27 interacts with HY5 and physically associates with the genomic regions to which HY5 binds, regulating the transcriptional activity of HY5 and its gene expression. Our results confirm that COR27 and COR28 work as transcriptional regulators and interact with other transcription factors to regulate the expression of at least 1,840 genes. When compared with Col-0, about evenly split between upregulation (53%) and downregulation (47%) in the cor27 cor28 mutant. Only a fraction of these genes (12.8%) were also regulated by HY5, indicating that COR27 and COR28 may interact with multiple transcription factors to regulate transcription.

HY5 protein also accumulated to higher levels in cor27 cor28 than in Col-0, consistent with the fact that COR27 and COR28 inhibited the transcription of HY5 (Supplemental Figures 6B and 6C). The long-hypocotyl phenotype of seedlings overexpressing YFP-COR27 was mostly suppressed in the cop1-6 background. It is interesting that COP1 is responsible for the degradation of COR27 in the dark but is also required for its function. One possible explanation for the suppression of the long hypocotyl phenotype of YFP-COR27 seedlings by cop1-6 would invoke an accumulation of HY5 protein. To test this possibility, we checked the protein levels of HY5 in Col-0, cop1-6, YFP-COR27, and YFP-COR27 cop1-6 (Supplemental Figures 6D and 6E). Our results indicated that indeed, there was more HY5 protein in cop1-6 and also in YFP-COR27 cop1-6 relative to Col-0 and YFP-COR27.

In summary, we showed that COR27 and COR28 are negative regulators of photomorphogenesis. COR27 and COR28 undergo COP1-mediated degradation in the dark. Light promotes the accumulation of HY5 and COR27, while COR27 physically interacts with HY5 to inhibit its transcriptional activity and fine-tune skotomorphogenesis development in the dark and photomorphogenic development in the light (Supplemental Figure 6F).

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

We used the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Columbia (Col-0) accession as wild type. The cor27 (CS834545), cor28 (SALK_137155), cor27 cor28, 35S:YFP-COR27, 35S:GFP-COR28, cop1-6, pro35S:MYC-COP1, hy5-215, hy5 (SALK_096651), and pifq (pif1 pif3 pif4 pif5) lines have been described in the literature (Ang and Deng, 1994; McNellis et al., 1994; Leivar et al., 2008; Li et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2016). Additional lines (YFP-COR27 cop1-6, GFP-COR28 cop1-6, and YFP-COR27 hy5-215) were generated by genetic crosses and combined phenotyping and genotyping of F2 progeny.

All seeds were surface-sterilized in 75% (v/v) ethanol for 10 min, washed four times with sterile water, then sown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with 0.8% (w/v) agar and 1% (w/v) Suc. Plates were then stratified for 4 d in the dark at 4°C before transfer to a growth chamber (AR-22L for white light, E-30LEDL3 for blue, red or far-red light; Percival Scientific) under either constant light, LD (16-h light/8-h dark), SD (8-h light/16-h dark), or constant-darkness conditions at 22°C. The lights used were white light (fluorescent light; 90 μmol/m2/s, cat. no. F17T8/TL841; Philips), blue light (light emitting diode [LED] light 40 μmol/m2/s), red light (LED light 40 μmol/m2/s), or far-red light (LED light 8 μmol/m2/s). The results of statistical analyses are shown in Supplemental Data Set 5.

Immunoblot Analysis

Seeds were grown for 7 d in SD conditions (white light) before being moved to blue or white light or darkness for 24 h, after we exposed seedlings to a defined light treatment (light to dark or dark to light for the indicated times). After treatment, we collected seedlings and prepared whole protein extracts with extraction buffer (25.2 g of glycerol, 0.02g of Bromophenol Blue, 4 g of SDS, 20 mL of 1-M Tris-HCl at pH 6.8, 3.1 g of DTT, and 50 mL of double-distilled water). Equal protein amounts were loaded and separated on a 10% or 12% (w/v) SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a Nitrocellulose Blotting Membrane (cat. no. P/N66485; PALL). We then probed the membrane with an anti-GFP antibody (cat. no. AE012, 1:3,000 dilution; Abclonal), stripped the blot, and re-probed with the anti-ACTIN antibody (cat. no. AC009, 1:3,000 dilution; Abclonal) as loading control.

Transcriptome Analysis

We extracted total RNA from 7-d–old Col-0, cor27 cor28, cop1-6, and hy5-215 seedlings grown in SD conditions and collected at ZT20 (12 h after lights off) under dim green light, using the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (cat. no. 1561; Ambion). We then generated mRNA sequencing libraries (with three independent biological replicates), which were sequenced by OE Biotech. We evaluated RNA integrity on a model no. 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The samples with an RNA integrity number ≥ 7 were subjected to further analysis. We generated libraries using a TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then these libraries were sequenced on an Illumina sequencing platform (HiSeq X Ten; Illumina) as 125-bp/150-bp paired-end reads. Sequenced reads were processed using Trimmomatic (v.0.36; http://www.usadellab.org/cms/index.php?page=trimmomatic). Reads containing multiple nitrogens and low-quality reads were removed to obtain clean reads. We then mapped the clean reads to the Arabidopsis reference genome (TAIR10.1_NCBI) using the software Hisat2 (v.2.2.1.0; https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2/manual.shtml). We then quantified read counts per gene and Fragments Per Kilobase exon per Million reads mapped values using the software Cufflinks (v.2.2.1; http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/install/), while read count values per transcript (protein_coding) were calculated using the softwares BowTie2 and eXpress (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml). We identified DEGs using the program DESeq (v.1.18.0; Anders and Hubre, 2013). The R package functions “Estimate Size Factors” and “nbinom Test,” Padjvalues < 0.05, and fold changes >1.5 were set as the threshold for significantly different expression. We downloaded the ChIP-chip (ChIP followed by microarray hybridization) data for HY5 from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession no. GSE6510). We performed a GO enrichment analysis (biological processes) using the GO website (http://geneontology.org) with the released version 2019-07-01.

RT-qPCR Analysis

We performed all RT-qPCR expression analyses as described in Ma et al. (2016). Briefly, we isolated total RNAs using a RNAiso Plus kit (Takara Bio). We synthesized first-strand cDNAs from 500 ng of starting total RNA using a Prime Script RT Reagent Kit with a genomic DNA Eraser (Takara Bio). We then used SYBR Premix Ex Tag (Takara Bio) and the MX3000 Real Time PCR System (Stratagene) for the qPCR reactions. We used the ISOPENTENYL DIPHOSPHATE ISOMERASE2 (IPP2, At3g02780) and ACTIN 7 (At5g09810) genes as internal controls. After initial denaturation of the first-strand cDNAs, we executed the following PCR program: denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, and a two-step PCR for 40 cycles (95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 20 s per cycle) with fluorescence read at the end of each cycle. A dissociation program was performed after the reaction. The biological replicates represent three independent experiments involving ∼20 seedlings per experiment. Three technical replicates were performed for each PCR reaction. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Data Set 4.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Analysis

We cloned the coding sequences of COR27 and COR28 in-frame with the GAL4 DNA binding-domain sequence in the bait vector pBridge (Takara Bio). We obtained the Arabidopsis cDNA library clones in the prey vector pACT from Dr. Joe Ecker (Salk Institute). We co-transformed the bait plasmid pBridge-COR27/COR28 and the prey plasmid library DNA into yeast strain Y190. Yeast cells were then grown on synthetic dropout medium (-Trp -Leu) plates for 4 d. We tested the interactions using β-galactosidase assays (168 μg/mL of substrate), checking the activity every h for eight h, and verified positive yeast clones by PCR and sequencing. The full list of identified COR27 and COR28 interactors is given in Supplemental Table 1. We fused the coding sequence of COP1 in-frame with the sequence of the GAL4 activation domain in the prey vector pGADT7 (Takara Bio).We cloned the coding sequence of HY5 into the pGADT7 or pDEST22 (Takara Bio) vectors to verify the interaction in yeast strain AH109 against pBridge-COR27, pBridge-COR28, or pDEST32-COR28.

BiLC Assays

We fused COR27/COR28 or COP1/HY5 to the N- or C terminus of firefly luciferase, then transformed the constructs into Agrobacterium (Agrobacterium tumefaciens) strain GV3101. We collected overnight Agrobacterium cultures by centrifugation at 3200g for 20 min and resuspended the cells in MES buffer (10 mM of MES,10 mM of MgCl2, and 100 mM of acetosyringone) to a final OD600 = 0.8 ∼ 1 before infiltration of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. We then returned infiltrated plants to LD conditions for 3 d. Before luciferase activity observation, we infiltrated leaves with luciferin solution (1 mM of luciferin and 0.01% [v/v] Triton X-100) and captured images immediately using a charge-coupled device camera (model no. Tanon-5200; BioTanon).

in Vitro Pull-Downs

We performed in vitro pulldown protein–protein interaction assays as previously described by Liu et al. (2008, 2013b) Ma et al. (2016), Liang et al. (2018), and Yang et al. (2018), with the following modifications. We cloned the full-length coding sequences of COR27 or COR28 into the pGEX4T-1 vector, and the full-length coding sequences of COP1 or HY5 into the pCold-TF vector. We then produced and purified the proteins in the Escherichia coli BL21 strain using Glutathione Sepharose 4B (cat. no. 17-0756-01; GE Healthcare) or Ni-NTA Agarose (cat. no. R901-15; Invitrogen). We then incubated equal amounts of eluted TF-His-COP1 or TF-His-HY5 with GST-COR27 or GST-COR28 in XB buffer (50 mM of Tris at pH 7.8, 500 mM of NaCl, 0.5% [v/v] Triton X-100, 1 mM of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 4.7 mM of 2-Mercaptoethanol, used to pull down the protein complexes with glutathione beads. We removed unbound proteins by washing with WB buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 7.8, 500 mM of NaCl,0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100, and 1 mM of PMSF), after which we eluted bound proteins and analyzed the resulting eluates by immunoblot analysis an anti-TF antibody (cat. no. M201, 1:3,000 dilution; Takara Bio) or anti-GST antibody (cat. no. G018, 1:3,000 dilution; Abcam).

Co-IPs

The co-IP procedure has been previously described by Liu et al. (2008, 2013b), Ma et al. (2016), Liang et al. (2018), and Yang et al. (2018). Briefly, we grew seedlings for 10 d from the genotypes Col-0, YFP-COR27 (in Col-0), and GFP-COR28 (in Col-0) in SD conditions, at which point we treated them with 50 mM of MG132 at ZT7.5 (30 min before lights off). We then moved seedlings into darkness at ZT8 for 4 h, collected and ground tissue in liquid nitrogen, and homogenized it in binding buffer (20 mM of HEPES at pH 7.5, 40 mM of KCl, 1 mM of EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mM of PMSF). We incubated protein extracts at 4°C for 10 min, before centrifugation at 14,000g for 10 min. We mixed the supernatant with 35 μL of anti-GFP-IgG-coupled protein A Sepharose (cat. no. KTSM1301; Alpalife), incubated the mixtures at 4°C for 30 min, and washed the beads three times with washing buffer (20 mM of HEPES at pH 7.5, 40 mM of KCl, 1 mM of EDTA, and 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100). We eluted bound proteins from the affinity beads with 4× SDS/PAGE sample buffer and analyzed the eluates by immunoblotting with anti-COP1 (cat. no. YKCP938, 1:2,000 dilution; Youke Biotech) and anti-HY5 (cat. no. PHY1908, 1:2,000 dilution; QWBIO) antibodies to detect the target proteins.

Yeast One-Hybrid Analysis

We cloned PIF4 promoter fragments (–1,703 bp to –1,231 bp, –1,286 bp to –785 bp, –870 bp to –435 bp, and –545 bp to –1 bp) into the pLacZi destination vector and transformed the resulting constructs into yeast strain YM4271. We also cloned the COR27 and HY5 coding sequences into the pDEST22 vector. We then transformed the resulting constructs into YM4271 cells containing the various promoter reporter plasmids. We grew cells in synthetic dropout medium (-Trp -Ura) and analyzed protein–promoter interactions using a β-galactosidase assay (with 168 μg/mL substrate added).

ChIP Assays

We performed ChIP experiments as previously described by Liu et al. (2008, 2013b), Ma et al. (2016), Liang et al. (2018), and Yang et al. (2018), using 10-d–old Col-0, YFP-COR27 (in Col-0), and HY5-HA (in the hy5-215 background) seedlings grown in SD conditions. We harvested 2 g of plant material, which we then cross linked with 1% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min under a vacuum. We stopped cross linking by the addition of Glc to the solution, to a final concentration of 0.125 M. We rinsed seedlings with water, froze them in liquid nitrogen, and ground them into a fine powder. We sonicated chromatin fragments (∼500 bp) with a bioruptor (Bioruptor Plus; Diagenode; at program 30 s on and 30 s off for 15 min) before immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP (cat. no. AE012; Abclonal) or anti-HA (cat. no. clone 3F10; Roche) antibodies and analyzed the precipitated DNA by qPCR with the indicated primer pairs (Supplemental Dataset 4). The level of binding was calculated as the ratio between the immunoprecipitation and Input proteins.

Transient Transcription Dual-Luciferase Assays

We performed transient transcription dual-luciferase assays using N. benthamiana plants as previously described by Liu et al. (2008). We used Agrobacterium cultures containing both the reporter construct (pGreen-PIF4pro:LUC) and the helper construct pSoup-P19, alone or mixed with Agrobacterium cultures containing the effector plasmids (pCambia1300-HY5-YFP, pEGAD-MYC-COR27, or pCambia1306-VP16HY5-Flag). We cloned the full-length coding sequences of COR27 and HY5 into pEGAD (the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center) at the EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites, resulting in pEGAD-MYC-COR27, into pCambia1300 and pCambia1306 (CAMBIA) at the BamHI and SalI sites, resulting in pCambia1300-HY5-YFP and pCambia1306-VP16HY5-Flag. We collected overnight Agrobacterium cultures by centrifugation at 3,200g for 20 min and resuspended pellets in infiltration buffer to a final OD600 = 0.8 ∼ 1, and infiltrated cell suspensions into healthy N. benthamiana leaves.

We performed protoplast isolation and PEG-mediated transformation as previously described by Liang et al. (2018) and Yang et al. (2018). We isolated protoplasts from three-week–old hy5-215 plants grown in SD conditions. We transfected protoplasts with a total of 20 μg of DNA (effector constructs 35S:COR27-GFP and 35S:HY5-GFP, and pGreen-HY5pro:LUC reporter) and incubated overnight. We measured luciferase activity using a luminometer (model no. GloMax 20/20; Promega) with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (model no. E1910; Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data for genes described in this article can be found in The Arabidopsis Information Resource under the following accession numbers: COR27 (At5g42900), COR28 (At4g33980), COP1 (At2g32950), HY5 (At5g11260), CRY1 (At4g08920), CRY2 (At1g04400), HYH (At3g17609), PIF4 (At2g43010), PRE1 (At5g39860), IAA29 (At4g32280), and SAUR23 (At5g18060). Accession numbers for 32 photomorphogenesis-related genes tested for interaction with COR27 are listed in Supplemental Table 2. RNA-seq data have been deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus with the following accession numbers: cor27 cor28 and cop1_RNA-seq GSE154409, hy5_RNA-seq GSE154416.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. The COR27 protein is degraded in the dark by the 26S proteasome and in CRY1 in a COP1-dependent manner.

Supplemental Figure 2. COR27 and COR28 inhibit photomorphogenesis in photoperiod condition.

Supplemental Figure 3. COR28 inhibits photomorphogenesis in a COP1-dependent manner.

Supplemental Figure 4. HY5 and PIFs regulate hypocotyl elongation in both LD and SD.

Supplemental Figure 5. HY5, but not COR27, binds the PIF4 promoter.

Supplemental Figure 6. A hypothetical model depicting COP1 regulates COR27, COR28 degradation and COR27, COR28 interact with HY5 to regulate gene expression and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis (Supports Figure 7).

Supplemental Table 1. Full list of identified COR27 or COR28 interactors.

Supplemental Table 2. Accession numbers for 32 photomorphogenesis-related genes tested for interaction with COR27.

Supplemental Data Set 1. List of 1,440 COR27- and COR28-regulated genes.

Supplemental Data Set 2. List of 3,854 COP1-regulated genes.

Supplemental Data Set 3. List of 2,157 HY5-regulated genes.

Supplemental Data Set 4. Primers list used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 5. Statistical analysis of t test and ANOVA results for the data shown in figures.

DIVE Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jigang Li and Jingbo Jin for materials and technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2017YFA0503800), the Foundation of Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (to X.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31670307, 31825004, 31721001, 31730009, 31670282, and 31701231), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant XDB27030000), and the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (grant 19XD1404400).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.L. and H.T.L. conceived the project; X.L. performed most of the experiments; C.C.L. performed the genomic expression analysis; Z.W.Z. and Y.W.L performed the RNA-seq analysis; D.B.M., J.Y.Z., and Y.Y made some of the constructs; X.L and H.T.L analyzed the data and wrote the article.

References

- Abbas, N., Maurya, J.P., Senapati, D., Gangappa, S.N., Chattopadhyay, S.(2014). Arabidopsis CAM7 and HY5 physically interact and directly bind to the HY5 promoter to regulate its expression and thereby promote photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 26: 1036–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders, S., Hubre, W.(2013). Differential Expression of RNA-seq Data at the Gene Level—the DESeq Package.. (Heidelberg, Germany: European Molecular Biology Laboratory; ). [Google Scholar]

- Ang, L.H., Chattopadhyay, S., Wei, N., Oyama, T., Okada, K., Batschauer, A., Deng, X.W.(1998). Molecular interaction between COP1 and HY5 defines a regulatory switch for light control of Arabidopsis development. Mol. Cell 1: 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang, L.H., Deng, X.W.(1994). Regulatory hierarchy of photomorphogenic loci: Allele-specific and light-dependent interaction between the HY5 and COP1 loci. Plant Cell 6: 613–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkert, M., Kozma-Bognár, L., Terecskei, K., De Veylder, L., Nagy, F., Ulm, R.(2014). UV-B-responsive association of the Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 with target genes, including its own promoter. Plant Cell 26: 4200–4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof, S.(2020). Chimeric activators and repressors define HY5 activity. Plant Cell 32: 793–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, W.R., Christie, J.M.(2002). Phototropins 1 and 2: Versatile plant blue-light receptors. Trends Plant Sci. 7: 204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burko, Y., Seluzicki, A., Zander, M., Pedmale, U.V., Ecker, J.R., Chory, J.(2020). Chimeric activators and repressors define HY5 activity and reveal a light-regulated feedback mechanism. Plant Cell 32: 967–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie, J.M., Arvai, A.S., Baxter, K.J., Heilmann, M., Pratt, A.J., O’Hara, A., Kelly, S.M., Hothorn, M., Smith, B.O., Hitomi, K., Jenkins, G.I., Getzoff, E.D.(2012). Plant UVR8 photoreceptor senses UV-B by tryptophan-mediated disruption of cross-dimer salt bridges. Science 335: 1492–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S., Hettiarachchi, G.H., Deng, X.W., Holm, M.(2006). Arabidopsis CONSTANS-LIKE3 is a positive regulator of red light signaling and root growth. Plant Cell 18: 70–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S., Johansson, H., Hettiarachchi, C., Irigoyen, M.L., Desai, M., Rubio, V., Holm, M.(2008). LZF1/SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG3, an Arabidopsis B-box protein involved in light-dependent development and gene expression, undergoes COP1-mediated ubiquitination. Plant Cell 20: 2324–2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarsy, E., Fankhauser, C.(2009). Higher plants use LOV to perceive blue light. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12: 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.W., Caspar, T., Quail, P.H.(1991). COP1: A regulatory locus involved in light-controlled development and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 5: 1172–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, J., Johansson, H., Hornitschek, P., Josse, E.M., Fankhauser, C., Halliday, K.J.(2011). Light receptor action is critical for maintaining plant biomass at warm ambient temperatures. Plant J. 65: 441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, S., Thomashow, M.F.(2002). Arabidopsis transcriptome profiling indicates that multiple regulatory pathways are activated during cold acclimation in addition to the CBF cold response pathway. Plant Cell 14: 1675–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangappa, S.N., Crocco, C.D., Johansson, H., Datta, S., Hettiarachchi, C., Holm, M., Botto, J.F.(2013). The Arabidopsis B-BOX protein BBX25 interacts with HY5, negatively regulating BBX22 expression to suppress seedling photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 25: 1243–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoecker, U.(2017). The activities of the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1/SPA, a key repressor in light signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 37: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, M., Ma, L.G., Qu, L.J., Deng, X.W.(2002). Two interacting bZIP proteins are direct targets of COP1-mediated control of light-dependent gene expression in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 16: 1247–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtan, H.E., et al. (2011). BBX32, an Arabidopsis B-Box protein, functions in light signaling by suppressing HY5-regulated gene expression and interacting with STH2/BBX21. Plant Physiol. 156: 2109–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X., Ouyang, X., Yang, P., Lau, O.S., Li, G., Li, J., Chen, H., Deng, X.W.(2012). Arabidopsis FHY3 and HY5 positively mediate induction of COP1 transcription in response to photomorphogenic UV-B light. Plant Cell 24: 4590–4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y., Lau, O.S., Deng, X.W.(2007). Light-regulated transcriptional networks in higher plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, O.S., Deng, X.W.(2012). The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends Plant Sci. 17: 584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S., Lee, S., Yang, K.Y., Kim, Y.M., Park, S.Y., Kim, S.Y., Soh, M.S.(2006). Overexpression of PRE1 and its homologous genes activates Gibberellin-dependent responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 47: 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar, P., Monte, E., Oka, Y., Liu, T., Carle, C., Castillon, A., Huq, E., Quail, P.H.(2008). Multiple phytochrome-interacting bHLH transcription factors repress premature seedling photomorphogenesis in darkness. Curr. Biol. 18: 1815–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar, P., Quail, P.H.(2011). PIFs: Pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci. 16: 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Ma, D., Lu, S.X., Hu, X., Huang, R., Liang, T., Xu, T., Tobin, E.M., Liu, H.(2016). Blue light- and low temperature-regulated COR27 and COR28 play roles in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell 28: 2755–2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian, H.L., He, S.B., Zhang, Y.C., Zhu, D.M., Zhang, J.Y., Jia, K.P., Sun, S.X., Li, L., Yang, H.Q.(2011). Blue-light-dependent interaction of cryptochrome 1 with SPA1 defines a dynamic signaling mechanism. Genes Dev. 25: 1023–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T., Mei, S., Shi, C., Yang, Y., Peng, Y., Ma, L., Wang, F., Li, X., Huang, X., Yin, Y., Liu, H.(2018). UVR8 interacts with BES1 and BIM1 to regulate transcription and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell 44: 512–523 e515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.(2002). Blue light receptors and signal transduction. Plant Cell 14: S207–S225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F., Jiang, Y., Li, J., Yan, T., Fan, L., Liang, J., Chen, Z.J., Xu, D., Deng, X.W.(2018). B-BOX DOMAIN PROTEIN28 negatively regulates photomorphogenesis by repressing the activity of transcription factor HY5 and undergoes COP1-mediated degradation. Plant Cell 30: 2006–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.L., Niu, D., Hu, Z.L., Kim, D.H., Jin, Y.H., Cai, B., Liu, P., Miura, K., Yun, D.J., Kim, W.Y., Lin, R., Jin, J.B.(2016). An Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase, SIZ1, negatively regulates photomorphogenesis by promoting COP1 activity. PLoS Genet. 12: e1006016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B., Zuo, Z., Liu, H., Liu, X., Lin, C.(2011). Arabidopsis cryptochrome 1 interacts with SPA1 to suppress COP1 activity in response to blue light. Genes Dev. 25: 1029–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Wang, Q., Liu, Y., Zhao, X., Imaizumi, T., Somers, D.E., Tobin, E.M., Lin, C.(2013a). Arabidopsis CRY2 and ZTL mediate blue-light regulation of the transcription factor CIB1 by distinct mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 17582–17587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Yu, X., Li, K., Klejnot, J., Yang, H., Lisiero, D., Lin, C.(2008). Photoexcited CRY2 interacts with CIB1 to regulate transcription and floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Science 322: 1535–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Li, X., Li, K., Liu, H., Lin, C.(2013b). Multiple bHLH proteins form heterodimers to mediate CRY2-dependent regulation of flowering-time in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D., Li, X., Guo, Y., Chu, J., Fang, S., Yan, C., Noel, J.P., Liu, H.(2016). Cryptochrome 1 interacts with PIF4 to regulate high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation in response to blue light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113: 224–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNellis, T.W., von Arnim, A.G., Deng, X.W.(1994). Overexpression of Arabidopsis COP1 results in partial suppression of light-mediated development: evidence for a light-inactivable repressor of photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 6: 1391–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen, M.D., Thomashow, M.F.(2009). A role for circadian evening elements in cold-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 60: 328–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M., Tepperman, J.M., Quail, P.H.(1998). PIF3, a phytochrome-interacting factor necessary for normal photoinduced signal transduction, is a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein. Cell 95: 657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund, M.T., Hardtke, C.S., Wei, N., Deng, X.W.(2000). Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature 405: 462–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedmale, U.V., Huang, S.C., Zander, M., Cole, B.J., Hetzel, J., Ljung, K., Reis, P.A.B., Sridevi, P., Nito, K., Nery, J.R., Ecker, J.R., Chory, J.(2016). Cryptochromes interact directly with PIFs to control plant growth in limiting blue light. Cell 164: 233–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolec, R., Ulm, R.(2018). Photoreceptor-mediated regulation of the COP1/SPA E3 ubiquitin ligase. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 45 (Pt A): 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail, P.H.(2002). Photosensory perception and signalling in plant cells: New paradigms? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14: 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzini, L., Favory, J.J., Cloix, C., Faggionato, D., O’Hara, A., Kaiserli, E., Baumeister, R., Schäfer, E., Nagy, F., Jenkins, G.I., Ulm, R.(2011). Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science 332: 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A., Ram, H., Abbas, N., Chattopadhyay, S.(2012). Molecular interactions of GBF1 with HY5 and HYH proteins during light-mediated seedling development in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 25995–26009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J.A., Deng, X.W.(2003). From seed to seed: The role of photoreceptors in Arabidopsis development. Dev. Biol. 260: 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Liang, T., Zhang, L., Shao, K., Gu, X., Shang, R., Shi, N., Li, X., Zhang, P., Liu, H.(2018). UVR8 interacts with WRKY36 to regulate HY5 transcription and hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 4: 98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi, C., Deng, X.W.(2005). COP1—from plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 15: 618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., He, H., Wang, X., Wang, X., Yang, X., Li, L., Deng, X.W.(2011). Genome-wide mapping of the HY5-mediated gene networks in Arabidopsis that involve both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Plant J. 65: 346–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Huai, J., Shang, F., Xu, G., Tang, W., Jing, Y., Lin, R.(2017). A PIF1/PIF3-HY5-BBX23 transcription factor cascade affects photomorphogenesis. Plant Physiol. 174: 2487–2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Z., Liu, H., Liu, B., Liu, X., Lin, C.(2011). Blue light-dependent interaction of CRY2 with SPA1 regulates COP1 activity and floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 21: 841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]