Abstract

Due to the severe adverse effects that can accompany conventional therapies for Crohn’s disease, the search for natural complementary therapies has increased dramatically in recent years. Indole-3-carbinol (I3C), a constituent of cruciferous vegetables, possesses anti-inflammatory properties; however, its effects on intestinal inflammation have yet to be evaluated. To test the hypothesis that I3C dampens intestinal inflammation, C57Bl/6 mice were treated with I3C and exposed to 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) to induce colitis. Several parameters of disease severity and inflammation were subsequently evaluated. I3C dampened the disease severity, as indicated by decreased body weight loss and decreased severity of clinical signs. Interestingly, this effect was observed in female but not male mice, which displayed a trend towards exacerbated colitis. Differential effects were observed in the profiles of cytokine production, as the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines was increased in males. The sex-specific effect of I3C in TNBS-induced colitis is a novel finding and warrants further investigation since this is a common dietary compound and is also available commercially.

Keywords: indole-3-carbinol (I3C), inflammation, Crohn’s disease

The desire to identify natural products to treat and prevent various diseases has increased dramatically in recent years due to the decreased satisfaction with conventional therapeutics. One compound of interest is indole-3-carbinol (I3C), a prevalent constituent of cruciferous vegetables including broccoli, brussel sprouts, and cabbage. I3C is primarily recognized for its potent anti-cancer properties since it has the unique ability to eliminate tumor cells while being protective in normal cells. Specifically, I3C has been reported to inhibit the proliferation of estrogen-sensitive breast cancer cells, induce apoptosis of melanoma cells, alter cell survival of prostate cancer cells, and generate adverse effects on other tumor cells (1–4). Activities contributing the observed effects of I3C include decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis, and decreased metastasis (reviewed in (5)). Importantly, no immediate or long-term severe adverse effects have been documented following human consumption in several cancer clinical trials (6–9) thereby emphasizing its usefulness as a therapeutic agent.

Several molecular targets have been identified for I3C and its metabolites, such as the primary acid condensation product diindolylmethane (DIM). I3C and DIM can bind several cytosolic receptors and alter several important signaling pathways including the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), estrogen receptor (ER), androgen receptor (AR), and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) (6–10). A complex signaling cascade is likely induced following I3C exposure due to crosstalk between these pathways including physical interaction of the ligand-bound AhR with NF-κB (10, 11) and the ER (12–14).

While I3C has been primarily investigated for its anti-cancer properties, there has been increased interest in evaluating its immunomodulatory properties. It has been documented that I3C can suppresses inflammation in vitro and in vivo in part by inhibiting NF-κB activation and decreasing production of inflammatory mediators (15–18). Therefore, the potential exists for this compound to be effective in reducing the severity of chronic inflammatory diseases including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, which are inflammatory bowel diseases. In fact, the I3C acid condensation product DIM suppressed disease severity of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis, which is an animal model of ulcerative colitis (19). However, the potential beneficial effects of its parent compound, I3C, on intestinal inflammation have yet to be investigated.

In this study we assessed the potential of I3C to suppress inflammation in a murine model of Crohn’s disease. We hypothesized that I3C would exert anti-inflammatory effects in the 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis. Our results demonstrate for the first time that I3C exerts sex-specific effects in TNBS colitis, as it ameliorates disease severity and inflammation in female, but not male, mice. I3C clearly has potential to be a useful therapeutic for intestinal inflammation; however, future studies are necessary to further define the sex-specific effects of this compound in the gut.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Laboratory animals

Six to eight week old male and female C57Bl/6 mice, originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), were bred and maintained in the animal research facility at the University of Montana. All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and maintained on 12 h dark/light cycles. Throughout each experiment animals were individually caged, and standard laboratory food and water were provided ad libilum. All protocols for the use of animals were approved by the University of Montana Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the current NIH guidelines for animal usage.

Chemicals

Indole-3-carbinol (I3C) at ~96% purity (as determined by HPLC) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and suspended in peanut oil, which was used as a vehicle control for gavages, at 10 mg/ml. The purity and stability of I3C was verified in house via NMR prior to use in our study. 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) was also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and dissolved in acetone/olive oil for pre-sensitization or 40% ethanol for enema administration.

Colitis induction

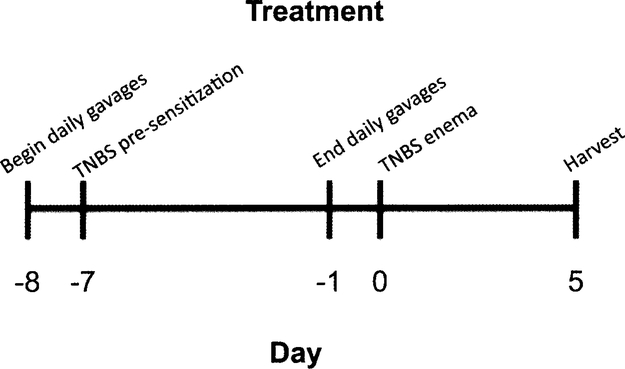

As described in Fig. 1, mice were gavaged daily starting on day −8 relative to the TNBS enema and ending on day-1 with 100 mg I3C per kg body weight (~200–250 μl total volume) or a comparable volume of peanut oil vehicle control prior to pre-sensitization and colitis induction. Pre-sensitization on day −7 included an application of 150 μl 5% TNBS in a 4:1 acetone:olive oil solution between the shoulder blades such that mice were not orally exposed to TNBS. Sham control mice that were gavaged with vehicle control and pre-sensitized with TNBS were harvested on day 0. Colitis was then induced via an enema containing TNBS on day 0, as previously described (18). Body weight loss and the severity of clinical symptoms (overall body condition, stool consistency, and dehydration state via a skin pinch test) was monitored daily and scored as previously described in detail (20). Briefly, each parameter was individually scored on a scale of 0–3 then combined to determine the total disease activity index. On day 5, mice were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. The TNBS model of colitis was utilized in these studies for its usefulness in testing new therapeutics and its similarity to human mucosal inflammatory responses. Animals were gavaged daily with 100 mg/kg I3C, peripherally pre-sensitized with 5% TNBS, intrarectally injected with 2.5 mg TNBS, and subsequently harvested on day 5 for evaluation.

Colon processing and histology

Colons were excised from each mouse and washed with PBS to remove debris. For histological analysis, a 1 cm section from the distal colon was fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, processed in the Shandon Citadel 2000 Automated Tissue Processor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with vacuum unit, embedded using the Shandon Histocentre 2 Embedding unit, sectioned at 7 μm using the Thermo Shandon Finesse 325 microtome, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in the Shandon Veristain 24–4 Slide Stainer. Colons were assessed microscopically by a blinded individual to determine the severity of inflammation based on an established scoring table (16). Briefly, colon damage was based on a combination of the severity of’ inflammatory cell infiltration into the tissue and the severity of tissue lesions. Both parameters were based on scales of 0–3 then combined for a total possible score of 6. Slides were imaged using the Nikon E800 Microscope with Cambridge Research Instrumentation, Inc. and Nuance camera software version 1.62 at 10X magnification. The remaining colon was divided into two sections for cell isolation and homogenization in lysis buffer from which the supernatants were analyzed for cytokine production, as described below.

Cytokine assays

Supernatants from homogenized colon tissue were examined for the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, and IFN-γ via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Samples were analyzed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using mouse cytokine-specific BD OptEIA ELISA kits (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) or R&D ELISA kits (Minneapolis, MN).

qRT-PCR

RNA was isolated from colon tissue with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and subjected to RNA clean-up using the Total RNA Kit with optional DNase treatment (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed using qScript cDNA Supermix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Resulting cDNA was subjected to qRT-PCR using commercially obtained primers (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD or Integrated DNA Technology, Coralville, IA, USA) including aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), aldehyde dehydrogenase family l, subfamily Al (ALDH1A1), aldehyde dehydrogenase family l, subfamily A2 (ALDHlA2), estrogen receptor alpha (ESRl), estrogen receptor beta (ESR2), indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 2 (ID02), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-10 (IL-10), interleukin-WA (IL-17A), interleukin-17F (IL-17F), interleukin-22 (IL-22), transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-βl), transforming growth factor-beta 2 (TGF-β2), and transforming growth factor-beta 3 (TGF-β3). Reactions were performed with PerfeCTa SYBR Green Supermix (Quanta Biosciences) on an Agilent Technologies Stratagene Mx3005P QPCR System (Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry

Lamina propria mononuclear cells from colonic tissue and cells from the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) were isolated and evaluated for expression of accessory molecules by flow cytometry, as previously described (Benson and Shepherd, 2011). Briefly, after cells were washed with PAB (1% bovine serum albumin and 0.l% sodum azide in PBS), they were blocked with Fc block (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) to eliminate non-specific staining. Subsequently, cells were stained for 10 min using optimal concentrations of fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. Antibodies used in these experiments included CD4-PE (GK1.5), CD25-PerCP/Cy5.5 (PC61), CD11c-APC (HL3), MHC2-FITC (M5/114.15.2), CD103-Pacific Blue (2E7), and their corresponding isotype controls, all of which were purchased from BioLegend or BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Two hundred thousand events were collected using a BD FACSAria flow cytometer and analyzed using FACSDiva (Version 6.1.2, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and FlowJo (Version 8.7.1, TreeStar, Inc., Ashland, OR) software programs.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0a for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Student’s t-test was used to compare vehicle-treated groups and I3C-treated groups while 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was used to compare multiple groups. Values p≤0.05 were determined to be significant.

RESULTS

Severity of TNBS-induced colitis is reduced with I3C treatment in females but not males

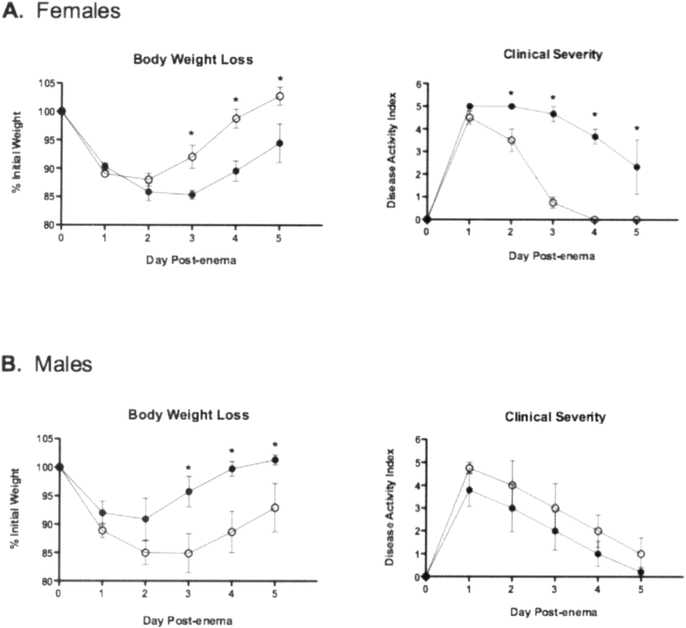

I3C is a prevalent dietary compound with anti-inflammatory properties so its potential to decrease inflammation in a murine model of colitis was evaluated. This compound has been used extensively in clinical trials with no serious long-term adverse effects reported. Therefore, the dose used in this study is comparable to a dose in humans taking I3C supplements (21). In order to assess the potential for I3C to ameliorate colitis, key indicators that mark the onset of Crohn’s disease, including significant body weight loss, loose stools and dehydration, and colon length were evaluated first using the design described in Fig. 1. Female mice treated with I3C did not lose as much weight and recovered more rapidly than vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2A). The clinical severity, as determined by the overall body condition, stool consistency, and dehydration state, was also significantly less severe in female I3C-treated mice. In addition, colon lengths on day 5 post-TNBS enema were significantly greater in female mice treated with I3C when compared to the vehicle controls (I3C, 7.2±0.3 cm vs vehicle, 6.2±0.2 cm; p = 0.02). Conversely, when compared to vehicle-treated mice, male mice treated with I3C lost weight, regained that weight more slowly, experienced a trend towards more severe clinical signs (Figure 2B), and did not have any significant differences in colon lengths (I3C, 7.1±0.1 cm vs vehicle, 6.8±0.3 cm; p = 0.17).

Fig. 2.

I3C ameliorates colitis in female, but not male, mice exposed to TNBS. Mice were monitored daily after disease induction for body weight loss and other clinical signs including body condition, dehydration slate, and stool consistency. Clinical severity was determined by combining the symptom scores for a total possible severity score of 9. Closed circles represent vehicle-treated mice, and open circles represent I3C-treated mice. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n=5) and representative of three separate experiments. *indicates significance of p≤0.05.

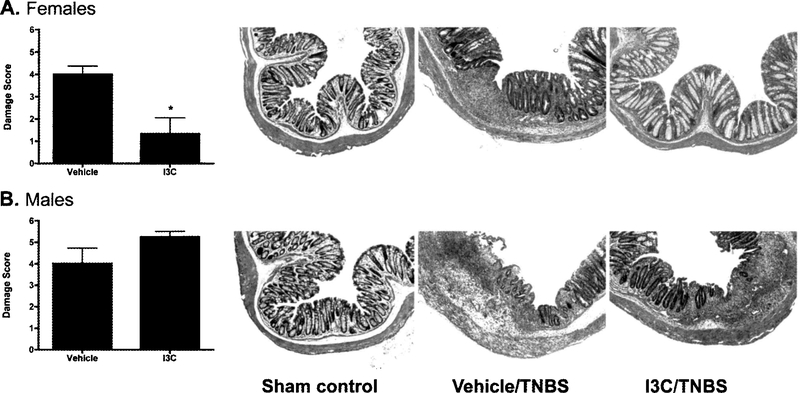

Inflammation and tissue damage in the colon decreases following treatment with I3C in females

Since intestinal inflammation associated with Crohn’s disease is transmural in nature, inflammatory cell infiltration and tissue lesions were evaluated in the colon. Relative to the sham controls (that did not receive the TNBS enema), TNBS-treated mice displayed significant histological damage on day 5 post-enema. However, in line with the observed clinical signs (as described above), female I3C-treated mice experienced significantly decreased inflammation in the colon when compared to vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 3A). Conversely, a trend towards increased colonic damage was observed in male I3C-treated mice relative to the vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Sex-specific effects of I3C on colon damage. Colon tissue was removed on day 5 post-enema and evaluated histologically to determine tissue damage. The final damage score was based on the severity inflammatory cell infiltration and mucosal lesions, both of which were scored on a scale of 0–3 then combined for a total colon damage score. Representative images from both female and male mice are displayed for sham controls, and TNBS-induced colitic mice treated with either vehicle or I3C. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n=5) and representative of three separate experiments. *indicates significance of P≤0.05.

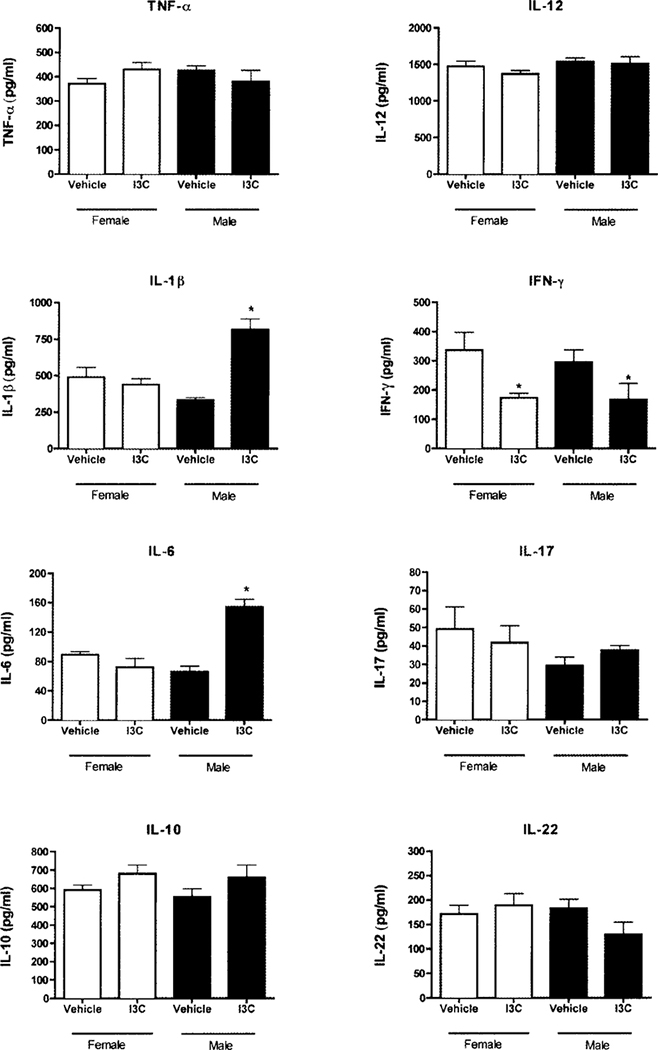

I3C exerts differential effects on cytokine production in colonic tissue of TNBS-exposed mice

Colitis is associated with significant production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. To better understand how I3C may alter the onset of Crohn’s disease, cytokine production in colonic tissue was measured. In I3C-treated female mice, the levels of the inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ decreased from 337 pg/ml to 174 pg/ml (Fig. 4). Production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 increased from 591 pg/ml to 680 pg/ml, but this was not statistically significant. It should be noted that IL-10 was significantly increased in one of the three experiments while just a trend towards increased IL-10 was observed in the other experiments. I3C did not significantly alter the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-lβ, IL-6, IL-12, IL-17 or IL-22 in female mice. In I3C-treated male mice, IL-lβ and IL-6 were both increased from 332 pg/ml to 817 pg/ml and from 66 pg/ml to 154 pg/ml, respectively. IFN-γ levels decreased from 296 pg/ml to 167 pg/ml. As with female mice, I3C did not alter the production of TNF-α, IL-12, IL-17 or IL-22.

Fig. 4.

I3C induces production of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory mediators in colonic tissue of TNBS-treated mice. Colon tissue was harvested five days after TNBS enema delivery, homogenized, and assessed for cytokine production. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n=5) and representative of three separate experiments. *indicates significance of p≤0.05.

Differential regulation of gene expression by I3C in TNBS-induced colitis

Since exposure to many dietary chemicals leads to the induction of regulatory genes (such as ALDH, IDO, and TGF-β) that correlates to decreased colitis, gene expression in the colons of mice was evaluated in vehicle- and I3C-treated mice five days after the TNBS enema. Interestingly, I3C-treated female mice downregulated IL-17A expression by 3.5-fold (relative to vehicle control-treated mice) while male mice treated with I3C upregulated IL-17A expression by 8.1-fold (Table I). A similar trend was observed with IL-6 expression with decreased levels in females and increased levels in males treated with I3C. Conversely, I3C-treated female mice upregulated TGF-β3 by 6.7-fold while male mice downregulated TGF-βl by 2.2-fold. There was also a trend of increased expression of ALDHlA2 in females while significantly decreased levels were observed in male mice. Notably, a trend existed for increased IL-IO expression for both female and male mice. Since I3C can interact with several receptors to elicit its effects, the changes in AHR and ESR gene expression were also evaluated. Expression levels of AHR, ESR1, and ESR2 were unchanged in both female and male mice on day 5, post-enema.

Table I.

Differential regulation of gene expression by I3C in TNBS-induced colitisa

| Female | Male | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Fold change | p-value | Fold change | p-value |

| AHR | −1.1 | 0.4 | 4.3 | 0.2 |

| ALDH1A1 | 1.2 | 0.4 | −1.2 | 0.4 |

| ALDH1A2 | 6.0 | 0.1 | −2.3* | 0.05 |

| ESR1 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 0.3 |

| ESR2 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 4.3 | 0.2 |

| IDO1 | −1.3 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| IDO2 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| IL6 | −2.4 | 0.08 | 4.1 | 0.2 |

| IL10 | 3.4 | 0.07 | 1.7 | 0.4 |

| IL17A | −3.5* | 0.05 | 8.1* | 0.05 |

| IL17F | −2.3 | 0.06 | −1.2 | 0.5 |

| IL22 | −1.7 | 0.3 | −1.1 | 0.5 |

| TGFB1 | 2.7 | 0.1 | −2.2* | 0.03 |

| TGFB2 | 1.8 | 0.2 | −1.6 | 0.06 |

| TGFB3 | 6.7* | 0.05 | −1.1 | 0.4 |

Colon tissue was harvested on day 5, homogenized in Trizol, and subjected to qRT-PCR to assess alterations in gene transcription. Fold change is relevant to vehicle-treated mice and normalized to β-actin. Data are representative of a single experiment with n=5 mice per treatment group.

indicates significance of p≤0.05.

Alterations in gut cell populations were not observed five days after TNBS enema

T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) are particularly important for maintaining homeostasis in the intestinal immune system. Therefore, cells were isolated from the colon tissue and the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and evaluated for phenotypic changes that could indicate the presence of regulatory cells following exposure to I3C. Five days after administration of the TNBS enema, no significant changes in T cells or DCs were observed (Table II).

Table II.

I3C does not significantly alter criticai immune cells in colona.

|

A.

Colon (Percent Population) | ||||

| Immune cell markers | Female | Male | ||

| Vehicle | I3C | Vehicle | I3C | |

| CD4 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 1.5 |

| CD25 | 77.9 ± 7.6 | 70.4 ± 5.5 | 67.5 ± 5.1 | 67.1 ± 15.4 |

| CD11c | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| MHC2 | 35.1 ± 10.3 | 40.1 ± 6.8 | 48.7 ± 6.2 | 36.8 ± 13.9 |

| CD103 | 73.1 ± 6.0 | 68.9 ± 4.6 | 64.2 ± 3.4 | 65.3 ± 11.2 |

| B. Colon (Mean Fluorescence Intensity) | ||||

| Immune cell markers | Female | Male | ||

| Vehicle | I3C | Vehicle | I3C | |

| CD4 | 536±51 | 492±18 | 512±21 | 520±21 |

| CD25 | 426±4 | 433±15 | 443±25 | 417±26 |

| CD11c | 570±73 | 620±78 | 651±21 | 559±102 |

| MHC2 | 3039±159 | 3072±153 | 2780±167 | 3166±405 |

| CD103 | 340±38 | 290±14 | 368±26 | 326±28 |

| C. MLNs (Percent Population) | ||||

| Immune cell markers | Female | Male | ||

| Vehicle | I3C | Vehicle | I3C | |

| CD4 | 18.3±0.9 | 21.8±1.4 | 26.1±3.1 | 20.2±4.4 |

| CD25 | 8.1±0.7 | 6.9±0.4 | 6.1 ±0.6 | 8.2± 1.6 |

| CD11c | 1.4±0.1 | 1.9±0.2 | 1.6±0.3 | 1.3±0.3 |

| MHC2 | 82.5±1.6 | 81.1±2.3 | 81.5±1.5 | 83.5±0.7 |

| CD103 | 18.3±2.6 | 14.2±1.0 | 11.7±1.0 | 17.4±4.9 |

| D. MLNs (Mean Fluorescence Intensity) | ||||

| Immune cell markers | Female | Male | ||

| Vehicle | I3C | Vehicle | I3C | |

| CD4 | 1115±21 | 1183±24 | 1176±37 | 1254±59 |

| CD25 | 296±23 | 472±17 | 465±14 | 488±23 |

| CD11c | 1208±70 | 1114±77 | 916±62 | 1042±160 |

| MHC2 | 5440±132 | 5196±273 | 5050±153 | 5009±257 |

| CD103 | 2094±235 | 2230±363 | 1819±308 | 1637±713 |

Leukocytes were isolated from colonic tissue and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) five days after enema administration. For T cells, CD25+ cells were gated out of the CD4+ population, and for dendritic cells MHC class 2+ and CD103+ cells were gated out of the CD11c+ population. Results are representative of three independent experiments (n=5).

DISCUSSION

The cruciferous vegetable constituent I3C is a potent anti-cancer agent, but its effect on inflammatory responses, especially in the gut, are not well documented. Since I3C and its primary metabolite DIM recently have been shown to produce anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects in vitro (16–18, 22), these compounds have the potential to elicit protective effects in diseases characterized by chronic inflammation. The current conventional medicines for Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract, can be accompanied by severe adverse effects so many patients have turned towards natural and complementary therapies as part of their treatment regimens. Consequently, we evaluated the potential of I3C to decrease the severity of Crohn’s disease using a murine model of colitis.

To characterize the effects of I3C on colitis, we evaluated the hallmark signs of disease onset: significant body weight loss, clinical severity, damage to colonic tissue, and inflammatory mediator production. I3C suppressed body weight loss, shortening of the colon and the severity of clinical signs, but this effect was surprisingly only observed in female mice while male mice displayed a trend to a more severe disease phenotype. Furthermore, inflammatory cell infiltration and tissue lesions were decreased in the colons of female, but not male, mice. The acid condensation product DIM has been reported to ameliorate the effects of DSS-induced colitis in terms of clinical signs and histological scoring of the gut tissue (19). Using the prototypical AhR ligand TCDD, our laboratory recently reported that TCDD dampened disease severity in TNBS-induced colitis (20). Because I3C (and DIM) can bind to the AhR with reasonably high-affinity relative to TCDD, our results support the hypothesis that the protective effects of I3C on gut inflammation in the TNBS-induced colitis model are via activation of the AhR signaling pathway. Future studies to specifically test this hypothesis should lead to a substantially greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying the effects of I3C in the gut.

Colitis induction is characterized by an increased production of inflammatory mediators. Thus, an important aspect of potential therapeutics would be to decrease the production of these damaging mediators. Interestingly the profile of cytokines produced in the gut was quite surprising. In our current study, we observed in female mice either significantly decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-17A) or trends to that effect (IL-6), whereas several of these inflammatory mediators (IL-lβ, IL-6, IL-17A) were significantly elevated in male mice exposed to TNBS. Interestingly, DIM was reported to inhibit the expression of several inflammatory mediators including nitric oxide, PGE2, as well the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-γ in the colons of DSS-treated colitic mice (19). Furthermore, NF-κB p65 activation was significantly decreased in the colonic tissue of DIM-treated mice relative to control-treated mice. Although similarities exist between these two IBD studies, they also differ in the strain of mice used (C57Bl/6 vs Balb/c), the type of IBD induced (Crohn’s disease vs. ulcerative colitis) and the form of I3C utilized (I3C vs DIM). Moreover, the study by Kim et al. failed to report the gender of mice used in their experiments, or if any gender differences existed following treatment of DSS-induced IBD.

More recently, our laboratory has shown that TCDD treatment of both female and male mice exposed to TNBS leads to decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12 and IFN-γ (20). Furthermore, TCDD treatment resulted in significant increases in the expression of AHRR, CYP1A1, and IDO1 but decreases in IL17A and IDO2 in the colons of mice after enema delivery. On the other hand, I3C decreased IL17A expression (3.5-fold) in females but increased its expression (8.1-fold) in male mice suggesting that this cytokine may be contributing towards increased inflammation in TNBS-treated mice. Interestingly, a similar trend was observed for protein levels of IL-17 in the colons of mice on day 5 post-enema. Because IL-17 plays a critical role in the development of TNBS-induced colitis in mice (23), I3C may represent a promising therapeutic for IBD based on its potential to disrupt this pro-inflammatory cytokine. Another effect of I3C in female mice was an increase (6.7-fold) in levels of TGF-β3 mRNA whereas TGF-βl expression was decreased (2.2-fold) in male mice treated with I3C. TGF-β is an important cytokine for the regulation of gut homeostasis and induced inflammatory responses in this mucosal compartment (24–26). In our study, an effect of increased TGF-β expression combined with decreased IL-6 production may result in the decreased levels of IL-17A and subsequently reduced gut inflammation that we observed in female mice. Conversely, decreased TGF-β expression combined with increased IL-6 levels may underlie the significant increase in IL-17A that was observed in male mice, an effect that could enhance their inflammatory response to TNBS in the colon. Future studies aimed at modulating the IL-17 signaling pathway may help define the divergent gender-specific effects of I3C in TNBS-exposed mice. Additionally, investigation of additional ligands for the AhR such as 2-(1’H-indole-3’-carbonyl)-thiazole-4-carboxylic acid methyl ester (ITE) would be of particular interest to explore for its potential to alter the development or severity of IBD because it has recently been reported to disrupt other immune-mediated diseases such as EAE (a murine model of multiple sclerosis) and oral tolerance in the gut (27–31).

Importantly, I3C, unlike TCDD, did not have lasting effects on AHRR or CYP1A1 gene expression in the colon tissue of TNBS-treated mice (data not shown), likely because I3C is much less stable than TCDD and thus prone to relatively rapid excretion. It also suggests that AhR activation alone may not be the primary mechanism underlying the suppression of colitis in females. These differences instead suggest that different mechanisms of action are responsible for mediating the effects of the dietary AhR ligands, TCDD and I3C. Since I3C possesses anti-estrogenic properties (5, 32), the estrogen receptor (ER) may also play a role, especially since the AhR and the ER have been demonstrated to physically interact, an outcome that has negative effects on the estrogen signaling pathway (12–14). Although we did not observe changes in ER expression five days after colitis induction, additional studies assessing the role of the ER in mediating the effects of I3C in TNBS colitis are clearly warranted.

Despite an underwhelming effect on pro-inflammatory cytokines in female mice on day 5 post-TNBS enema in our study, I3C may be acting on several important immune cells in the gut to ameliorate colitis. Dendritic cells (DCs) play important role in maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis. In a recent report from our laboratory, we demonstrated that bone marrow-derived DCs grown in the presence of I3C and cultured with antigen-specific naïve CD4+ T cells induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) (18). Therefore, it is possible that DCs increased Tregs in the gut consequently leading to the decreased gut inflammation observed in I3C-exposed mice. This would be consistent with what we observed in TNBS-treated mice exposed to TCDD (20). Although we did not observe any significant alterations in cell populations on day 5 post-enema, it is plausible that the functions of DCs and T cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes and colon tissue were altered earlier in the inflammatory response as we previously reported with TCDD. Thus, there may be direct and/or indirect effects of I3C on T cells in the gut, and this possibility should be further evaluated.

Taken together, our results demonstrate the novel finding that I3C imparts sex-specific effects in the TNBS colitis model. Since these findings could have significant implications for Crohn’s disease patients consuming increased amounts of cruciferous vegetables and/or I3C dietary supplements, additional studies are warranted to define the specific mechanisms responsible for the divergent effects on colonic inflammation induced by I3C.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant number ES013784 (DMS) and by award number F31AT005557 (JMB) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NCCAM. The authors wish to thank the CEHS Fluorescent Imagery Core (supported in part by NIH grants RR017670 and RR015583) and the Fluorescence Cytometry Core (supported by the NIH grant RR017670) at UM for their support.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: ALL AUTHORS REPORT NO CONFLICTS OF INTEREST RELEVANT TO THIS ARTICLE.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler S, Rashid G, Klein A. Indole-3-carbinol inhibits telomerase activity and gene expression in prostate cancer cell lines. Anticancer Res 2011;31:3733–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad A, Sakr WA, Rahman KM. Novel targets for detection of cancer and their modulation by chemopreventive natural compounds. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012; 4:410–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SY, Kima DS, Jeong YM, Moon SI, Kwon SB, Park KC. Indole-3-carbinol and ultraviolet B induce apoptosis of human melanoma cells via down-regulation of MITF. Pharmazie 2011; 66:982–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marconett CN, Singhal AK, Sundar SN, Firestone GL. Indole-3-Carbinol disrupts Estrogen Receptor-alpha dependent expression of Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Receptor and Insulin Receptor Substrate-l and proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal BB, Ichikawa H. Molecular targets and anticancer potential of indole-3-carbinol and its derivatives. Cell Cycle 2005; 4:1201–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradlow HL, Michnovicz JJ, Halper M, Miller DG, Wong GY, Osborne MP. Long-term responses of women to indole-3-carbinol or a high fiber diet. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1994; 3:591–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed GA, Peterson KS, Smith HJ, Gray JC, Sullivan DK, Mayo MS, Crowell JA, Hurwitz A. A phase I study of indole-3-carbinol in women: tolerability and effects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005; 14:1953–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong GY, Bradlow L, Sepkovic D, Mehl S, Mailman J, Osborne MP. Dose-ranging study of indole-3-carbinol for breast cancer prevention. J Cell Biochem Suppl 1997; 28–29: 111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen CA, Bryson Pc. Indole-3-carbinol for recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: long-term results. J Voice 2004; 18:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogel CF, Sciullo E, Matsumura F. Involvement of RelB in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated induction of chemokines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007; 363:722–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel CF, Sciullo E, Li W, Wong P, Lazennec G, Matsumura F. RelB, a new partner of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription. Mol Endocrinol2007; 21:2941–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtake F, Takeyama K, Matsumoto T, Kitagawa H, Yamamoto Y, Nohara K, Tohyama C, Krust A, Mimura J, Chambon P, Yanagisawa J, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Kato S. Modulation of oestrogen receptor signalling by association with the activated dioxin receptor. Nature 2003; 423:545–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews J, Wihlen B, Thomsen J, Gustafsson JA. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription: ligand-dependent recruitment of estrogen receptor alpha to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-responsive promoters. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25:5317–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wormke M, Stoner M, Saville B, Walker K, Abdelrahim M, Burghardt R, Safe S. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediates degradation of estrogen receptor alpha through activation of proteasomes. Mol Cell Biol 2003; 23:1843–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takada Y, Andreeff M, Aggarwal BB. Indole-3-carbinol suppresses NF-kappaB and IkappaBalpha kinase activation, causing inhibition of expression of NF-kappaB-regulated antiapoptotic and metastatic gene products and enhancement of apoptosis in myeloid and leukemia cells. Blood 2005; 106:641–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang HP, Wang ML, Hsu CY, Liu ME, Chan MH, Chen YH. Suppression of inflammation-associated factors by indole-3-carbinol in mice fed high-fat diets and in isolated, co-cultured macrophages and adipocytes. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai JT, Liu HC, Chen YH. Suppression of inflammatory mediators by cruciferous vegetable-derived indole-3-carbinol and phenylethyl isothiocyanate in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. Mediators Inflamm 2010; 2010:293642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson JM, Shepherd DM. Dietary ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor induce anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects on murine dendritic cells. Toxicol Sci 2011; 124:327–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim YH, Kwon HS, Kim DH, Shin EK, Kang YH, Park JR, Shin HK, Kim JK. 3,3’-diindolylmethane attenuates colonic inflammation and tumorigenesis in mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15:1164–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benson JM, Shepherd DM. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by TCDD reduces inflammation associated with Crohn’s disease. Toxicol Sci 2011;120:68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minich DM, Bland JS. A review of the clinical efficacy and safety of cruciferous vegetable phytochemicals. Nutr Rev 2007; 65:259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho HJ, Seon MR, Lee YM, Kim J, Kim JK, Kim SG, Park JH. 3,3’-Diindolylmethane suppresses the inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide in murine macrophages. J Nutr 2008; 138:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Zheng M, Bindas J, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls JK. Critical role of IL-17 receptor signaling in acute TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006; 12:382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feagins LA. Role of transforming growth factor-beta in inflammatory bowel disease and colitis-associated colon cancer. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:1963–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory lymphocytes and intestinal inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27:313–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Munoz F, Dominguez-Lopez A, Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Role of cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14:4280–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korn T How T cells take developmental decisions by using the aryl hydrocarbon receptor to sense the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:20597–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quintana FJ, Basso AS, Iglesias AH, Korn T, Farez MF, Bettelli E, Caccamo M, Oukka M, Weiner HL. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2008; 453:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quintana FJ, Murugaiyan G, Farez MF, Mitsdoerffer M, Tukpah AM, Bums EJ, Weiner HL. An endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand acts on dendritic cells and T cells to suppress experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:20768–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner HL, da Cunha AP, Quintana F, Wu H. Oral tolerance. Immunol Rev 2011; 241:241–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeste A, Nadeau M, Bums EJ, Weiner HL, Quintana FJ. Nanoparticle-mediated codelivery of myelin antigen and a tolerogenic small molecule suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc NatlAcad Sci U S A 2012; 109:11270–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auborn KJ, Fan S, Rosen EM, Goodwin L, Chandraskaren A, Williams DE, Chen D, Carter TH. Indole-3-carbinol is a negative regulator of estrogen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]