Abstract

Background.

Cancer mortality is higher in counties with high levels of (current) poverty, but less is known about associations with persistent poverty. Persistent poverty counties (with ≥20% of residents in poverty since 1980) face social, structural, and behavioral challenges that may make their residents more vulnerable to cancer.

Methods.

We calculated 2007–2011 county-level, age-adjusted, overall and type-specific cancer mortality rates (deaths/100,000 people/year) by persistent poverty classifications, which we contrasted with mortality in counties experiencing current poverty (≥20% of residents in poverty according to 2007–2011 American Community Survey). We used two-sample t-tests and multivariable linear regression to assess mortality by persistent poverty, and compared mortality rates across current and persistent poverty levels.

Results.

Overall cancer mortality was 179.3 (standard error [SE]=0.55) deaths/100,000 people/year in non-persistent poverty counties and 201.3 (SE=1.80) in persistent poverty counties (12.3% higher, p<.0001). In multivariable analysis, cancer mortality was higher in persistent poverty versus non-persistent poverty counties for overall cancer mortality as well as for several type-specific mortality rates: lung and bronchus; colorectal; stomach; and liver and intrahepatic bile duct (all p<.05). Among counties experiencing current poverty, those counties that were also experiencing persistent poverty had elevated mortality rates for all cancer types as well as lung and bronchus; colorectal; breast; stomach; and liver and intrahepatic bile duct (all p<.05).

Conclusions.

Cancer mortality is higher in persistent poverty counties than other counties, including those experiencing current poverty.

Impact.

Etiologic research and interventions, including policies, are needed to address multilevel determinants of cancer disparities in persistent poverty counties.

Keywords: Cancer mortality, poverty, persistent poverty, socioeconomic status, disparities, measurement

Cancer is the second leading cause of death among men and women in the United States.1 Over the last several decades, advances in cancer prevention, diagnosis, and care have resulted in improved early detection tests, lower cancer mortality, higher survival rates, and overall better outcomes for patients.2,3 Despite these advances, disparities continue to exist across the cancer control continuum among people living in poverty.2 Individual-level poverty is associated with substantial cancer risk4 due to increased exposure to carcinogens, low educational attainment, and lack of access to care.2,5 In addition, people living in poverty have high rates of cancers caused by occupational, recreational, or lifestyle exposures (e.g., colorectal, laryngeal, liver, lung) and by human papillomavirus infection (e.g., anal, cervical, oral).2,3,5,6

Many studies use area-level measures of poverty (e.g., at the county level) to (1) approximate individual-level poverty, despite concerns raised with the validity of such a practice7, as well as (2) reflect some dimension of the social and physical environment in which people live.8 The most common area-level definition used in such studies is ‘≥20% of population living in poverty’2,5,6,9 (i.e., current poverty). However, additional definitions exist, including persistent poverty10, which is defined as ‘≥20% of population living in poverty since 1980.’11,12

Persistent poverty counties represent an important subgroup of counties experiencing current poverty over time, yet little empirical research has investigated the impact that the duration of time over which these counties have experienced high levels of poverty has on disease burden. Warnecke and colleagues13 suggest that health disparities are the result of social, institutional, physical, individual, and biological factors, which impact health directly, indirectly, and interactively. Several of these factors vary for persistent poverty versus other counties, even when compared to other counties experiencing current poverty. Compared to other areas, persistent poverty counties have greater minority populations, more children under the age of eighteen, less formal education, and greater unemployment.12,14,15 In addition, residents of these counties face greater exposure to cancer risk factors (e.g., higher rates of obesity14 as well as cigarette smoking, sun exposure, alcohol consumption, and HPV infection16). Little research is available to help understand the environmental and multilevel influences on health that could vary for persistent poverty counties versus other counties. However, differences in social and health policies, institutional resources and access, social support, and issues around embodiment17 of social inequity into physical inequity may negatively impact health in persistent poverty counties.13,18,19 Understanding the burden of mortality from cancer (overall and from selected cancer sites) in counties experiencing persistent poverty can provide insight into potential causal mechanisms linking county-level poverty and other contextual factors to health outcomes and cancer disparities.

This study will examine (overall and type-specific) cancer mortality rates for persistent poverty counties versus non-persistent poverty counties. In addition, this study will compare poverty-related disparities in mortality rates for three mutually-exclusive groups: (1) not experiencing current poverty; (2) experiencing current but not persistent poverty; and (3) experiencing current and persistent poverty. These analyses will identify potential differences in conclusions based on these definitions. The findings of this study can motivate future studies to further examine persistent poverty and its relation to cancer and to identify potential causal mechanisms and help inform and locate future interventions to reduce cancer disparities.

Materials and Methods

Data sources and measures

Cancer mortality.

Data on county-level cancer mortality came from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), accessed through SEER*Stat (National Cancer Institute).20 NCHS links data from the National Death Index with population estimates to calculate age-adjusted mortality rates from a variety of causes, including cancer. From NCHS, we gathered 2007–2011 age-adjusted mortality rates for each county in the United States for (1) all cancer types; for highly prevalent cancer types: (2) lung and bronchus, (3) colorectal, (4) breast, and (5) prostate; and for selected infection-associated cancer types: (6) cervical, (7) oropharyngeal, (8) stomach, and (9) liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancers. Mortality rates were calculated as number of deaths per 100,000 people, except for breast and cervical cancers (calculated as deaths per 100,000 females) and prostate cancer (calculated as deaths per 100,000 males).

Poverty definitions.

The first definition of county-level poverty was persistent poverty (our focal poverty classification). The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines counties as experiencing persistent poverty if they had ≥20% of residents classified as poor (i.e., below the federal poverty level) by the decennial censuses in 1980, 1990, and 2000, and by the American Community Survey21 (ACS)’s five-year (2007–2011) estimates.10 The second definition was current poverty2,5,6,9, that is, if counties had ≥20% of residents below the federal poverty level according to the ACS five-year (2007–2011) estimates.

Sociodemographics.

To characterize each group of counties, we gathered total population (from ACS 2007–2011)21, metropolitan status (from the USDA’s rural-urban continuum codes22), Census region, sex and racial/ethnic compositions, levels of educational attainment, unemployment rate, and median household income, in $1000s (from ACS 2007–2011 estimates).21

Statistical analysis

First, we generated descriptive statistics for the sociodemographic variables to characterize (1) all U.S. counties, (2) all non-persistent poverty counties, and (3) persistent poverty counties.

Our primary inferential analysis assessed differences in cancer mortality rates for counties experiencing persistent poverty versus counties not experiencing persistent poverty (i.e., mutually-exclusive groups covering all U.S. counties). This approach is most similar to existing studies examining disparities in cancer burden associated with (current) area-level poverty. We calculated the mean and standard error of the county-level mortality rates (for all cancers and for each cancer type under study) separately for non-persistent poverty counties and for persistent poverty counties. We used two-sample t-tests to evaluate unadjusted differences in the cancer mortality rates across persistent poverty groups. Next, we conducted multivariable linear regression to estimate adjusted differences in cancer mortality, controlling for county-level metropolitan status, Census region, percent of residents that are female, racial/ethnic composition, education levels, unemployment, and median household income (these variables were considered potential confounders).

Then, we contrasted mortality rates across three mutually-exclusive groups of counties that cover the entire U.S.: counties defined as (1) not experiencing current poverty; (2) experiencing current but not persistent poverty; and (3) experiencing current and persistent poverty. This approach provides insight into distinctions between definitions of poverty; that is, by examining whether and to what extent persistent poverty counties differ from current (but not persistent) poverty counties and from counties not experiencing current poverty, we can generate evidence to identify these counties as a vulnerable setting deserving of additional etiologic and intervention research. We generated the mortality rates for these three types of counties to allow for descriptive comparisons. In addition, we conducted two-sample t-tests and multivariable linear regression to assess unadjusted and adjusted (respectively) differences in cancer mortality between currently impoverished counties that were non-persistent poverty (group 2) versus currently impoverished counties that were also persistent poverty (group 3).

Analyses used a two-sided p-value of .05. Per federal regulations, this project was exempt from review by an institutional review board because it involved secondary analysis of publicly-available, deidentified datasets.

Results

Three hundred and ninety-five counties were defined as experiencing persistent poverty (Table 1), representing 20,668,553 residents. Persistent poverty counties were primarily rural (83.0%) and concentrated in the Southern Census region (79.2%). Persistent poverty counties were demographically distinct from non-persistent poverty counties (p<.05 for all comparisons between persistent poverty and non-persistent poverty counties for variables in Table 1). Compared to other counties in the U.S., persistent poverty counties had lower percentages of non-Hispanic white residents (mean=56.6% versus 81.6% in non-persistent poverty counties; p<.0001) and higher percentages of non-Hispanic black residents (mean=24.7% versus 6.6%; p<.0001) and Hispanic residents (mean=10.8% versus 7.7%; p<.01), with lower percentages of residents who obtained a high school or bachelor’s degree (both p<.0001). Additionally, median household income was almost a third lower in persistent poverty counties (mean=$32,339; median=$32,156; interquartile range [IQR]=$28,705–36,020) versus non-persistent poverty counties (mean=$47,154; median=$44,745; IQR=$39,883–51,440) (p<.0001).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for counties in the United States by poverty characteristics, 2007–2011.

| All U.S. (k=3,143) | Non-Persistent Poverty (k=2,748) | Persistent Poverty (k=395) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | p | ||||

| Metropolitan status | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Non-metropolitan | 1976 | 62.8 | 1648 | 60.0 | 328 | 83.0 | ||||

| Metropolitan | 1167 | 37.1 | 1100 | 40.0 | 67 | 17.0 | ||||

| Census region | <.0001 | |||||||||

| Northeast | 217 | 6.9 | 214 | 7.8 | 3 | 0.8 | ||||

| Midwest | 1055 | 33.6 | 1012 | 36.8 | 43 | 10.9 | ||||

| South | 1423 | 45.3 | 1110 | 40.4 | 313 | 79.2 | ||||

| West | 448 | 14.3 | 412 | 15.0 | 36 | 9.1 | ||||

| mean | median | IQR | mean | median | IQR | mean | median | IQR | p | |

| % of residents that are female | 50.0 | 50.5 | [49.6–51.2] | 50.0 | 50.5 | [49.6–51.1] | 50.3 | 50.7 | [49.6–51.9] | 0.03 |

| Racial/ethnic composition | ||||||||||

| % Non-Hispanic white | 78.5 | 85.8 | [67.3–94.2] | 81.6 | 87.4 | [72.9–94.5] | 56.6 | 55.4 | [37.1–76.8] | <.0001 |

| % Non-Hispanic black | 8.8 | 2.0 | [0.5–10.1] | 6.6 | 1.7 | [0.5–7.9] | 24.7 | 22.7 | [0.8–43.5] | <.0001 |

| % Hispanic | 8.1 | 3.2 | [1.5–8] | 7.7 | 3.4 | [1.7–8.2] | 10.8 | 1.9 | [0.9–5.3] | <.01 |

| Education levels | ||||||||||

| % High school degree or higher | 83.7 | 85.2 | [79.2–89.1] | 85.0 | 86.1 | [81.2–89.5] | 74.7 | 74.7 | [70.4–79.1] | <.0001 |

| % Bachelor’s degree or higher | 19.3 | 17.1 | [13.3–22.8] | 20.0 | 17.8 | [14.1–23.5] | 14.3 | 12.2 | [10.1–15.6] | <.0001 |

| % unemployed | 8.1 | 7.9 | [5.8–10] | 7.6 | 7.5 | [5.6–9.6] | 11.5 | 10.9 | [8.6–13.5] | <.0001 |

| Household income, $1000s | 45.3 | 43.4 | [37.8–50.2] | 47.2 | 44.7 | [39.9–51.4] | 32.3 | 32.2 | [28.7–36.0] | <.0001 |

Note. P-values indicate results of chi-square tests (for metropolitan status and Census region) and two-sample t-tests comparing demographic characteristics for non-persistent poverty counties versus persistent poverty counties. IQR=interquartile range.

In 2007–2011, a total of 871 counties were classified as experiencing current poverty, comprised of 395 persistent poverty counties and 476 experiencing current but not persistent poverty. These subgroups of current poverty counties (i.e., also experiencing persistent poverty versus not also experiencing persistent poverty) were demographically similar to each other (all p>.05 for all comparisons).

Comparing cancer mortality rates for persistent poverty counties versus non-persistent poverty counties

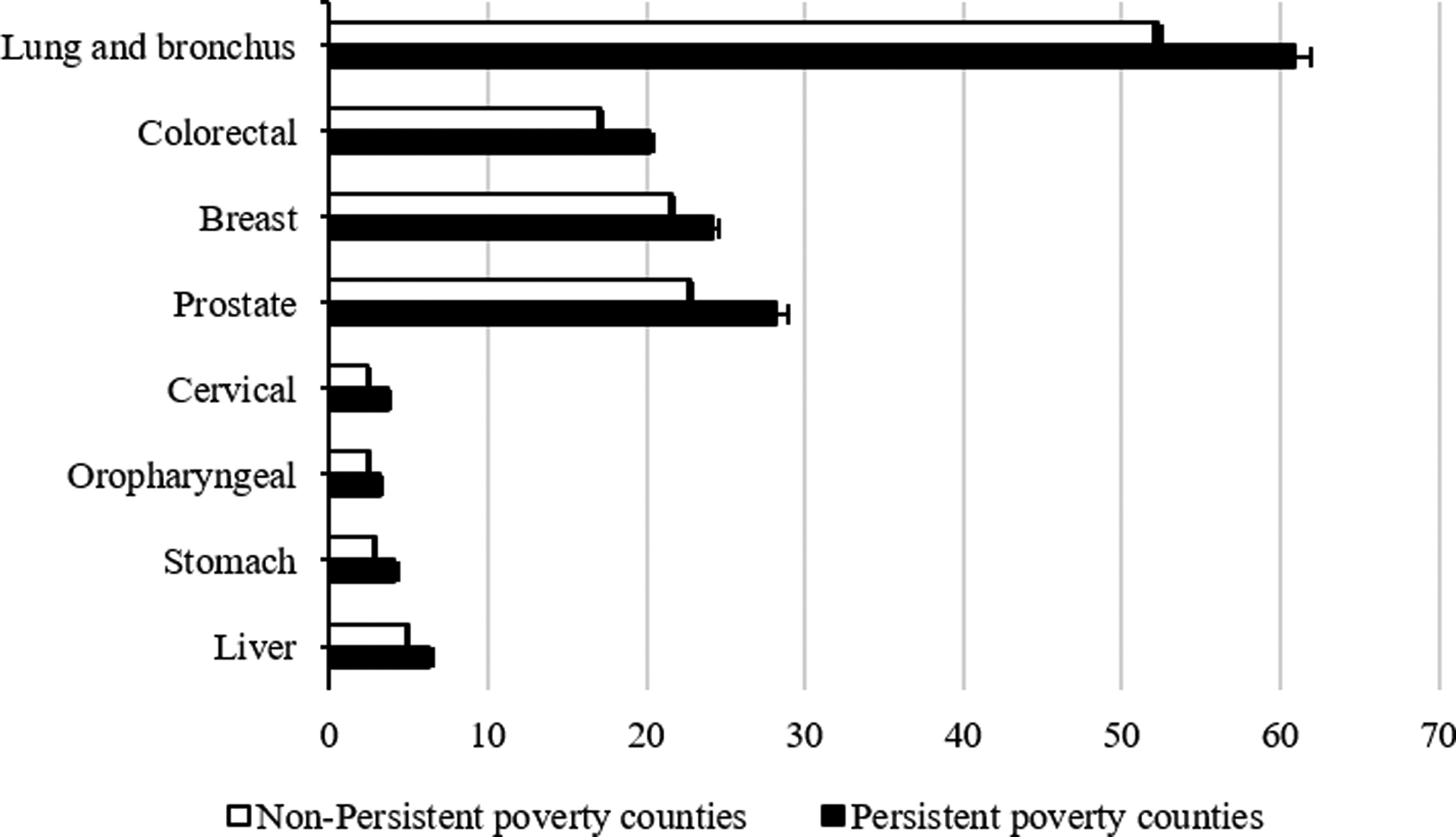

For the whole U.S., the 2007–2011 overall cancer mortality rate was 182.1 (standard error [SE]=0.6) deaths per 100,000 people per year. This figure was 179.3 (SE=0.6) in non-persistent poverty counties and 201.3 (SE=1.8) in persistent poverty counties, indicating that overall cancer mortality was 12.3% higher in persistent poverty counties than in non-persistent poverty counties (unadjusted parameter estimate (est.)=22.0 additional deaths per 100,000 people per year, p<.0001) (Table 2). After controlling for county-level sociodemographics, the difference in overall cancer mortality rate for persistent poverty versus non-persistent poverty counties was attenuated but still statistically significant (adjusted est.=8.3 additional deaths, p<.0001). For each cancer type, cancer mortality was 11–50% higher in persistent poverty counties than in non-persistent poverty counties in unadjusted analyses (Table 2; Figure 1; all p<.0001). After adjusting for demographic characteristics, mortality was higher in persistent poverty counties than non-persistent poverty counties for lung and bronchus cancer (adjusted est.=2.9 additional deaths, p<.001), colorectal cancer (adjusted est.=1.7, p<.0001), stomach cancer (adjusted est.=0.4, p=.01), and liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer (adjusted est.=0.5, p<.01).

Table 2.

Comparisons of 2007–2011 cancer mortality rates for the entire U.S. versus counties defined by persistent poverty.

| Non-Persistent Poverty (ref) | Persistent Poverty | Unadjusted difference | Adjusted difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SE | mean | SE | % diff | est. | p | est. | p | |

| All cancer types | 179.3 | 0.6 | 201.3 | 1.8 | 12.3 | 22.0 | <.0001 | 8.3 | <.0001 |

| Lung and bronchus | 52.3 | 0.3 | 60.9 | 1.0 | 16.5 | 8.6 | <.0001 | 2.9 | <.001 |

| Colorectal | 17.1 | 0.1 | 20.1 | 0.3 | 17.7 | 3.0 | <.0001 | 1.7 | <.0001 |

| Breast | 21.6 | 0.2 | 24.1 | 0.5 | 11.9 | 2.6 | <.0001 | 0.9 | 0.10 |

| Prostate | 22.8 | 0.2 | 28.2 | 0.7 | 24.0 | 5.5 | <.0001 | 1.1 | 0.08 |

| Cervical | 2.5 | 0.1 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 50.1 | 1.2 | <.0001 | 0.4 | 0.07 |

| Oropharyngeal | 2.5 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 29.6 | 0.7 | <.0001 | 0.1 | 0.38 |

| Stomach | 2.9 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 0.2 | 43.2 | 1.3 | <.0001 | 0.4 | 0.01 |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile duct | 5.0 | 0.1 | 6.3 | 0.2 | 27.6 | 1.4 | <.0001 | 0.5 | <.01 |

Note. Cancer mortality rates are expressed as deaths per 100,000 people per year, except breast and cervical cancers (deaths per 100,000 females per year) and prostate cancer (deaths per 100,000 males per year). Two-sample t-tests were used to estimate unadjusted differences in cancer mortality rates for counties not in persistent poverty (reference category) versus counties in persistent poverty, and multivariable linear regressions were used to estimate adjusted differences in cancer mortality rates. Adjusted models controlled for county-level metropolitan status; Census region; percent of residents that are female, Non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, with a bachelor’s degree or higher, and unemployed; and median household income. Ref=reference; SE=standard error; diff=difference; est.=parameter estimate.

Figure 1.

2007–2011 age-adjusted cancer mortality rates for non-persistent poverty versus persistent poverty counties. Cancer mortality rates are expressed as deaths per 100,000 people per year, except breast and cervical cancers (deaths per 100,000 females per year) and prostate cancer (deaths per 100,000 males per year).

Comparing cancer mortality rates among counties (1) not experiencing current poverty, (2) experiencing current but not persistent poverty, and (3) experiencing current and persistent poverty

Counties that were not experiencing current poverty (or, as a result, persistent poverty) had lower cancer mortality rates than other counties (Table 3). For example, the overall cancer mortality rate was 177.6 (SE=0.6) in non-current poverty counties, compared to 187.4 (SE=1.3) in current but not persistent poverty counties and 201.3 (SE=1.8) in current and persistent poverty counties.

Table 3.

Comparison of 2007–2011 cancer mortality rates for three mutually-exclusive groups of U.S. counties: (1) not experiencing current poverty, (2) experiencing current but not persistent poverty, and (3) experiencing current and persistent poverty.

| (1) Not Current Poverty | Current Poverty | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) Not Persistent Poverty (ref) | (3) Persistent Poverty | Unadjusted difference (2 v. 3) | Adjusted difference (2 v. 3) | ||||||||

| mean | SE | mean | SE | mean | SE | % diff | est. | p | est. | p | |

| All cancer types | 177.6 | 0.6 | 187.4 | 1.3 | 201.3 | 1.8 | 7.4% | 13.9 | <.0001 | 9.6 | <.0001 |

| Lung and bronchus | 51.3 | 0.3 | 57.0 | 0.7 | 60.9 | 1.0 | 6.7% | 3.8 | <.01 | 2.8 | <.01 |

| Colorectal | 17.0 | 0.1 | 17.6 | 0.3 | 20.1 | 0.3 | 14.7% | 2.6 | <.0001 | 1.7 | <.001 |

| Breast | 21.5 | 0.2 | 22.0 | 0.4 | 24.1 | 0.5 | 9.7% | 2.1 | <.0001 | 1.6 | 0.03 |

| Prostate | 22.4 | 0.2 | 24.3 | 0.5 | 28.2 | 0.7 | 16.3% | 4.0 | <.0001 | 0.4 | 0.65 |

| Cervical | 2.3 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 13.8% | 0.4 | 0.26 | 0.8 | 0.08 |

| Oropharyngeal | 2.4 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 14.1% | 0.4 | <.01 | 0.3 | 0.08 |

| Stomach | 2.8 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 4.1 | 0.2 | 19.1% | 0.7 | <.01 | 0.5 | 0.05 |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile duct | 4.8 | 0.1 | 5.6 | 0.1 | 6.3 | 0.2 | 13.7% | 0.8 | <.001 | 0.7 | <.01 |

Note. Cancer mortality rates are expressed as deaths per 100,000 people per year, except breast and cervical cancers (deaths per 100,000 females per year) and prostate cancer (deaths per 100,000 males per year). Two-sample t-tests were used to estimate unadjusted differences in cancer mortality rates for (2) counties experiencing current but not persistent poverty (reference category) versus (3) counties experiencing current and persistent poverty, and multivariable linear regressions were used to estimate adjusted differences in cancer mortality rates. Adjusted models controlled for county-level metropolitan status; Census region; percent of residents that are female, Non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, with a bachelor’s degree or higher, and unemployed; and median household income. Ref=reference; SE=standard error; diff=difference; est.=parameter estimate.

Focusing only on counties experiencing current poverty, those that were also experiencing persistent poverty had significantly elevated cancer mortality rates (Table 3). For each cancer type except cervical cancer, cancer mortality was 7–19% higher in current and persistent poverty counties than in current but not persistent poverty counties. After adjusting for demographic characteristics, mortality was higher in current and persistent poverty counties than in current but not persistent poverty counties for lung and bronchus cancer (adjusted est.=2.8 additional deaths per 100,000 people per year, p<.01), colorectal cancer (adjusted est.=1.7, p<.001), breast cancer (adjusted est.=1.6, p=.03), stomach cancer (adjusted est.=0.5, p<.05), and liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer (adjusted est.=0.7, p<.01).

Discussion

Overall, persistent poverty counties have significantly higher cancer mortality rates than other U.S. counties, including counties experiencing current (but not persistent) poverty. That is, persistent poverty is associated with increased cancer mortality risk, over and above the risk associated with current poverty. Some of these differences are reduced when controlling for other county-level sociodemographic characteristics, suggesting that some of these variables are confounded with each other (e.g., a portion of the unadjusted difference may be due to the effect of rurality on cancer mortality23). Additional research is needed to tease apart these differences. However, residents of persistent poverty counties remain at increased risk for death from lung and bronchus cancer, colorectal cancer, stomach cancer, and liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer. To our knowledge, this study is the first national evaluation of the association between persistent poverty and mortality from a number of cancer sites, as well as the first study to evaluate the difference in magnitude of cancer disparities observed when using a “current poverty” versus a “persistent poverty” definition. The reasons for the observed increases in cancer mortality could be related to factors such as patterns of risk behaviors, infrastructure, healthcare access, and/or the social determinants of health.13,24 Importantly, research indicates that material disadvantage, including area-level poverty, can get “under the skin” and change physiological processing to put individuals at greater risk for cancer and other chronic diseases.17,25 For example, people living in persistent poverty counties may have higher levels of chronic stress (due to factors such as insecure employment, adverse experiences, social isolation, etc.) that could give rise to physiological aberrations (e.g., chronic inflammation) that result in elevated cancer incidence.26 The implications of the present findings are two-fold. First, etiologic research is needed to untangle the complex, multilevel causal relationships that give rise to these disparities. Second, given that overall cancer mortality in persistent poverty counties is 12% higher than all other U.S. counties, and 7% higher than other counties experiencing current (but not persistent) poverty, interventions are urgently needed to reduce the disparate and elevated rates of cancer mortality among residents of these vulnerable, persistent poverty counties.

As noted, the results from this study indicate striking disparities in cancer mortality for persistent poverty counties compared to other counties. Overall cancer mortality rates were 12% higher in persistent poverty counties than in all other (non-persistent poverty) U.S. counties, which is approaching the magnitude of racial disparities in cancer mortality for blacks versus whites (around 15.8%).3 Across cancer types, large differences were observed, especially for lung and bronchus cancer (16.5% higher), colorectal cancer (17.7% higher), stomach cancer (43.2% higher), and liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer (27.6%). Lung and bronchus cancer and colorectal cancer have strong behavioral causes27, and stomach cancer and liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer are associated at least in part with infections28; studies and interventions to reduce cancer mortality rates in persistent poverty counties will need to address these cancer risk factors. However, the role of social determinants of health (e.g., poverty and discrimination; access to quality healthcare; physical and social environments) cannot be ignored. Persistent poverty counties may have experienced decades of disinvestment in public health and other sectors, resulting in multiple, multilevel vulnerabilities. Conceptual work suggests that even if we address “downstream” causes of disease, such as behavioral risks, disparities may continue to be observed29 due to the contextual and compositional challenges facing these counties.

In addition, mortality rates were 7–19% higher in counties that experienced both persistent and current poverty compared to counties that only experienced current poverty. These findings suggest that living in a persistent poverty county is associated with additional risk over and above shorter-term poverty. Thus, the long-term duration of exposure to poverty in these counties is associated with elevated cancer mortality risk for their residents. Researchers should carefully select and justify their selection when choosing from among these definitions of poverty, since use of one measure versus another may have implications for study findings. In particular, longitudinal studies may benefit from using the persistent poverty definition since it reflects a stable adverse exposure over long periods of time. Additional research, including qualitative investigation, is needed to understand the unique lived experiences among residents of current poverty versus persistent poverty counties, and how differences in these conditions may give rise to disparities within the broader category of “current poverty” counties.

The exact reasons for the elevated cancer mortality rates in persistent poverty counties versus other counties are not yet known. As described above, impoverished counties tend to have high rates of cancer risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, obesity14,16) and low rates of cancer screening.30,31 In addition, larger-scale, infrastructural issues, such as reduced access to healthcare32, could contribute to mortality risk. Disinvestment in clinical and public health systems is a problem in any community, but in these persistent poverty counties—which are primarily rural and have had high rates of poverty for more than 30 years—infrastructure may be especially underequipped to deal with the burden of cancer in an aging population now and in the future. It is therefore crucial to understand area-level poverty as a marker of exposure to carcinogenic environments.

This study had several strengths. We used several high-quality datasets with near-complete coverage of the U.S. population, including cancer outcomes. Our analysis of cancer mortality by persistent and current poverty categories is an important contribution to the existing research on (1) health outcomes in these counties, (2) social determinants of cancer, and (3) poverty-related disparities in cancer. In terms of limitations, our cross-sectional analysis could not account for residential history, precluding a meaningful investigation of duration of exposure to persistent poverty over the lifecourse. In addition, county size (in population and area) is variable across the country, which could affect the statistical power of the analyses. Additional methodologic and theoretical work is needed to explicate the role of county size on geographic studies of health. Finally, this observational, ecological study excluded many individual-level variables relevant to geographic differences in cancer mortality, including in- and out-migration33 as well as individual-level attitudes (e.g., cancer fatalism34) and behaviors (e.g., smoking16). Future multilevel studies should incorporate these factors to better characterize the burden of cancer among populations living in persistent poverty counties. A related limitation for ecological studies, including this one, is that their findings cannot be generalized to individual-level relationships.

In conclusion, persistent poverty counties faced substantially higher cancer mortality rates than other counties, with particularly large disparities for mortality from all cancer types, as well as from lung and bronchus cancer, colorectal cancer, stomach cancer, and liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer. Future etiologic research should attempt to better understand the higher rates of cancer mortality in these counties. These disparities are likely the result of social, institutional, physical, individual, and biological factors that have developed over more than 30 years of elevated poverty in these vulnerable counties, and targeted, multilevel interventions to reduce them are urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared or accomplished by the authors as part of official duty at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the view of the NIH, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government. No external financial support was provided

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Heron MP. Deaths: Leading causes for 2016. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2018;67(6). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2004;54(2):78–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cronin KA, Lake AJ, Scott S, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broder S Progress and challenges in the National Cancer Program In: Brugge J, Curran T, Harlow E, McCormick F, eds. Origins of human cancer: A comprehensive review. Plainfield, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1991:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boscoe FP, Johnson CJ, Sherman RL, Stinchcomb DG, Lin G, Henry KA. The relationship between area poverty rate and site‐specific cancer incidence in the United States. Cancer. 2014;120(14):2191–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. Persistent area socioeconomic disparities in U.S. incidence of cervical cancer, mortality, stage, and survival, 1975–2000. Cancer. 2004;101(5):1051–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;156(5):471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger N Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(5):703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu X, Cokkinides V, Chen VW, et al. Associations of subsite‐specific colorectal cancer incidence rates and stage of disease at diagnosis with county‐level poverty, by race and sex. Cancer. 2006;107(S5):1121–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States Department of Agriculture. Descriptions and maps: County economic types, 2015 edition. 2017; https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes/descriptions-and-maps/, 2018.

- 11.Miller KK, Weber BA. Persistent poverty across the rural-urban continuum. 2003; https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/18910, 2019.

- 12.Miller KK, Crandall MS, Weber BA. Persistent Poverty and Place: How do persistent poverty and poverty demographics vary across the rural-urban continuum. Paper presented at: Measuring Rural Diversity2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, et al. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: the National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1608–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett KJ, Probst JC, Pumkam C. Obesity among working age adults: the role of county-level persistent poverty in rural disparities. Health & Place. 2011;17(5):1174–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beale CL. The ethnic dimension of persistent poverty in rural and small-town areas In: Swanson LL, ed. Racial/Ethnic Minorities in Rural Areas: Progress and Stagnation, 1980–90. Vol Agricultural Economic Report No. 731. Rural Economy Division, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanderpool RC, Mills LA. Cancer prevention and control in rural communities In: Crosby RA, Wendel ML, Vanderpool RC, Casey BR, eds. Rural populations and health: Determinants, disparities, and solutions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2012:341–356. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger N Defining and investigating social disparities in cancer: critical issues. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2005;16(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2012;2012(44):2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golden SD, Earp JA. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health education & behavior : the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 2012;39(3):364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute. SEER*Stat software (seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) version 8.3.2. 2019; https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/, 2019.

- 21.U. S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). 2018; https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/, 2018.

- 22.United States Department of Agriculture. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes: Overview. 2013; http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx, 2018.

- 23.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: An analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):992–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor SE, Repetti RL, Seeman T. Health psychology: what is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annual review of psychology. 1997;48:411–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(2):60–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cancer Institute. Risk factors for cancer. 2015; https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sawyers CL, Abate-Shen C, Anderson KC, et al. AACR cancer progress report 2013. Clinical Cancer Research. 2013;19(20 Supplement):S1–S98. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss JL, Liu B, Feuer EJ. Urban/Rural Differences in Breast and Cervical Cancer Incidence: The Mediating Roles of Socioeconomic Status and Provider Density. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(6):683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett KJ, Pumkam C, Bellinger JD, Probst JC. Cancer screening delivery in persistent poverty rural counties. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2011;2(4):240–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crawford SM, Sauerzapf V, Haynes R, Zhao H, Forman D, Jones AP. Social and geographical factors affecting access to treatment of lung cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;101(6):897–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molloy R, Smith CL, Wozniak AK. Internal migration in the United States. J Econ Perspect. 2011;25(3):173–196. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crosby RA, Collins T. Correlates of Community-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Rural Population: The Role of Fatalism. The Journal of Rural Health. 2017;33(4):402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]