Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Use of smokeless tobacco (SLT) with other tobacco products is growing, yet gaps in understanding transitions among SLT and other product use remain. The aim of this study is to examine cross-sectional prevalence and longitudinal pathways of SLT use among U.S. youth (12–17 years), young adults (18–24 years), and adults 25+ (25 years and older).

DESIGN:

Data were drawn from the first three waves (2013–2016) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, a nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of US youth and adults in the U.S.Respondents with data at all three waves (youth, N = 11,046; young adults, N = 6,478; adults 25+, N = 17,188) were included in longitudinal analyses.

RESULTS:

Young adults had the highest current SLT use compared with other age groups. Among Wave 1 (W1) past 30-day youth and young adult SLT users, most were SLT and cigarette polytobacco users compared with adults 25+, who more often used SLT exclusively. Among W1 exclusive SLT users, persistent exclusive use across all three waves was more common among adults 25+, while transitioning from exclusive SLT use to SLT polytobacco useat W2 or W3 was more common among youth and young adults. Among W1 SLT and cigarette polytobacco users,a common pathway wasdiscontinuing SLT use but continuing other tobacco use.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our results showed distinct longitudinal transitions among exclusive and SLT polytobacco users. Deeper understanding of these critical product transitions will allow for further assessment of population health impact of these products.

INTRODUCTION

Smokeless tobacco (SLT) products are non-combusted tobacco products that are available in two main types in the USA: chewing tobacco and moist snuff, including snus.1 They are available in pouched or loose forms and sold in a variety of flavours.2–7 In the past few years, new brands of SLT have entered the market, adding to the already diverse SLT products. For example, Swedish-style moist snuff tobacco, snus, steadily increased its market share in the USA between 2009 and 2014.8 Although snus has been used in Sweden since the early 19th century,9 cigarette companies such as Philip Morris and R.J. Reynolds acquired SLT companies and introduced snus exhibiting their well-established and widely recognized brand names (Marlboro snus and Camel snus, respectively).5,7

There have been consistent declines in overall US cigarette smoking since the mid-1960s; however, SLT use in adult men has increased since 1960 but plateaued over the past decade.10-13 According to National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in 2014, approximately 8.7 million (3.3%) Americans ages 12 years or older had past 30-day (P30D) use of SLT, including 6.2 million (3.0%) ages 26 years and older, 2.0 million (5.6%) ages 18–25 years and 490 000 (2.0%) ages 12–17 years, showing highest prevalence among young adults compared with youth and older adults.13 SLT is also often used in conjunction with other tobacco products, particularly cigarettes.14,15 Examining 2013–2014 Wave 1 (W1) data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, among US youth ages 12–17 years, only 0.4% exclusively used SLT, while 1.0% used SLT with other tobacco products, indicating higher polytobacco use among youth SLT users.12 Also W1 data from the PATH Study showed that polytobacco use is common among SLT users, with SLT and cigarettes being the most common combination.16 Approximately 4% of US adults and youth used cigarettes and SLT, making it the fourth most common polytobacco combination among US adults and youth in 2013–2014.12 Compared with users of other SLT products, users of pouched snus were more likely to be polytobacco users but less likely to use the products daily.16 The use of SLT products in conjunction with other tobacco products on the US market, especially cigarettes, is prevalent16 yet there are gaps in understanding transitions to and from exclusive SLT use and polytobacco use.14 Understanding SLT use in the USA has become even more pertinent after the passage of the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which gave the US Food and Drug Administration the authority to regulate tobacco products, including SLT.17

To advance understanding of SLT use in the USA, this study examines differences between each of the first three waves of cross-sectional estimates of ever, past 12 months (P12M), P30D and daily P30D SLT use for US youth (ages 12–17 years), young adults (ages 18–24 years) and adults 25+ (ages 25 years and older) from 2013 to 2016 (Aim 1). Using the first three waves of longitudinal within-person data from the PATH Study, this study also examines age group differences in pathways of persistent use, discontinued use and reuptake of SLT across the waves among W1 P30D SLT users (Aim 2). Moreover, this study compares longitudinal transitions of use among W1 exclusive SLT users, W1 SLT users who use multiple tobacco products including cigarettes (SLT polytobacco use w/CIGS) and W1 SLT users who use multiple tobacco products excluding cigarettes (SLT polytobacco use w/o CIGS) (Aim 3). Exploring longitudinal transitions of use and non-use of SLT products separately for exclusive and polytobacco users provides deeper understanding of critical product transitions.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

The PATH Study is an ongoing, nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of youth (ages 12–17 years) and adults (ages 18 years or older) in the USA. Self-reported data were collected using audio computer-assisted self-interviews administered in English and Spanish. Further details regarding the PATH Study design and W1 methods are published elsewhere.18,19 At W1, the weighted response rate for the household screener was 54.0%. Among screened households, the overall weighted response rate was 78.4% for youth and 74.0% for adults at W1, 87.3% for youth and 83.2% for adults at W2 and 83.3% for youth and 78.4% for adults at W3. Details on interviewing procedures, questionnaires, sampling, and weighting, response rates and accessing the data are available at https://doi.org/10.3886/Series606. The study was conducted by Westat and approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board. All participants ages 18 years and older provided informed consent, with youth participants ages 12–17 years providing assent while their parent/legal guardian provided consent.

The current study reports cross-sectional estimates from 13 651 youth and 32 320 adults who participated in W1 (data collected 12 September 2013–14 December 2014), 12 172 youth and 28 362 adults at W2 (23 October 2014–30 October 2015) and 11 814 youth and 28 148 adults at W3 (19 October 2015–23 October 2016). The differences in the number of completed interviews between W1, W2 and W3 reflect attrition due to non-response, mortality and other factors, as well as youth who enrolled in the study at W2 or W3.18 We also report longitudinal estimates from W1 youth (n=11 046), W1 young adults (n=6478) and W1 adults 25+ (n=17 188) with data collected at all three waves. See online supplementary figure 1 for a detailed description of the analytic sample for longitudinal analysis.

Measures

Tobacco use

At each wave, youth and adult respondents were asked about tobacco use behaviors for cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), traditional cigars, cigarillos, filtered cigars, pipe tobacco, hookah, snus pouches, other SLT and dissolvable tobacco. Participants were asked about P30D use of ‘e-cigarettes’ at W1 and W2 and ‘e-products’ (e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes and e-hookah) at W3; all electronic products noted above are referred to as ENDS in this paper. Youth respondents were also asked about their use of bidis and kreteks, but these data were not taken into consideration in the analyses due to small sample sizes.

The PATH Study questionnaires describe SLT as smokeless tobacco products that are put in the mouth and frequently chewed, sucked or spitted and snus pouches, a type of SLT that comes in a small pouch that are put inside the lip. In this paper, SLT includes both SLT and snus pouches. Generic pictures and descriptions of SLT products are displayed on the screen for respondents prior to questioning, and common brands such as Redman, Levi Garrett, Beechnut, Skoal, Grizzly, Nordic Ice and Copenhagen are provided as examples. The PATH Study first asked respondents if they use: (1) snus pouches or (2) loose snus, moist snuff, dip, spit or chewing tobacco. Those who used snus pouches are further asked if they used the brand Skoal Bandits (a non-snus SLT that is available in pouches). Participants report ‘used only Skoal Bandits’, ‘used both Skoal Bandits and other brands of snus pouches’, or ‘did not use Skoal Bandits’. Based on the responses, users are classified as snus pouch users or as other smokeless (including Skoal Bandits) users.16 For each tobacco product, questions regarding ever use and frequency of use are asked.

Outcome measures

Cross-sectional definitions of use included ever, P12M, P30D and daily P30D use. Longitudinal outcomes included persistent use (ie, continued exclusive or SLT polytobacco use at W2 and W3), discontinued use (ie, stopped SLT use at W2 and W3 or just W3) and reuptake of use (ie, SLT use at W1, stopped SLT use at W2 and used SLT again at W3), as well as switching and transitions among SLT exclusive and polytobacco SLT users. The definition of each outcome is included in the footnote of the table/figure in which it is presented.

Analytic Approach

To address Aim 1, weighted cross-sectional prevalence of SLT use was estimated for ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D at each wave stratified by age and by gender. Cross-sectional weighted estimates of SLT product type (snus or other smokeless products) use at each wave (stratified by age) were also examined. For Aim 2, irrespective of other tobacco product use, longitudinal W1-W2-W3 transitions in P30D SLT use were summarized to represent pathways of persistent any P30D SLT use, discontinued any P30D SLT use, and reuptake of any P30D SLT use at W3. Finally, to address Aim 3, longitudinal W1-W2-W3 SLT use pathways that flow through seven mutually exclusive transition categories were examined for three W1 SLT user groups (W1 P30D exclusive SLT use, W1 P30D SLT polytobacco use w/CIGS, and W1 P30D SLT polytobacco use w/o CIGS; see Supplemental Figure 2). For each aim, weighted t-tests were conducted on differences in proportions to assess statistical significance. To correct for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted.Given that combustible cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product with the most robust evidence base of harmful health consequences,10 two polytobacco user groups were examined separately to compare longitudinal transitions among polytobacco users who use and who do not use combustible cigarettes. These pathways represent building blocks that can be aggregated to reflect higher-level behavioral transitions.

Cross-sectional estimates (Aim 1) were calculated using PATH Study cross-sectional weights for W1 and single-wave (pseudo-cross-sectional) weights for W2 and W3. The weighting procedures adjusted for complex study design characteristics and non-response. Combined with the use of a probability sample, the weighted data allow these estimates to be representative of the non-institutionalized, civilian, resident US population aged 12 years or older at the time of each wave. Longitudinal estimates (Aims 2 and 3) were calculated using the PATH Study W3 all-waves weights. These weighted estimates are representative of the resident US population aged 12 years and older at the time of W3 (other than those who were incarcerated) who were in the civilian, non-institutionalized population at W1.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Survey Procedures, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).Variances were estimated using the balanced repeated replication method20with Fay’s adjustment set to 0.3to increase estimate stability.21Analyses were run on the W1-W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8). Estimates with low precision (those based on fewer than 50 observations in the denominator or with a relative standard error greater than 0.30) were flagged and are not discussed in the Results.Respondents missing a response to a composite variable (e.g., ever, P30D) were treated as missing; missing data were handled with listwise deletion.

RESULTS

Cross-Sectional Weighted Prevalence

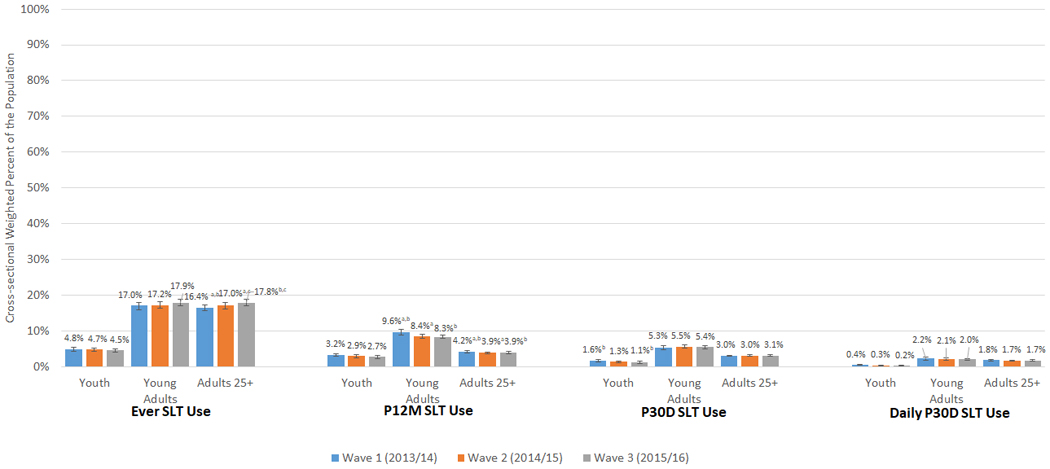

As shown in Figure1 (Aim 1), ever SLT use was fairly constant at all three waves among youth and young adults but increased at each wave for adults 25+. Prevalence of P12MSLT use decreased slightly from 9.6%(95% CI: 8.9–10.3) to 8.3% (95% CI: 7.8–8.9) among young adults, and from 4.2%(95% CI: 3.9–4.5) to 3.9%(95% CI: 3.6–4.2) among adults 25+. Prevalence of P30D use decreased significantly among youth from 1.6% (95% CI: 1.3–1.9) at W1 to 1.1% (95% CI: 0.9–1.4) at W3. Males had higher prevalence of ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D SLT use at each wave compared to females across all three age groups (data not shown in tables).

Figure 1:

Cross-sectional Weighted Percent of Ever, P12M, P30D, and Daily P30DSLT Use Among Youth, Young Adults, and Adults 25+ in Wl, W2, and W3 of the PATH Study

Abbreviations: P12M = past 12-month; P30D = past 30-day; SLT = smokeless tobacco; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3 W1/W2/W3 ever SLT use unweighted Ns: youth (ages 12-17) = 629/525/474; young adults (ages 18-24) = 1,942/1,610/1,560; adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) = 5,369/4,807/4,727W1/W2/W3 P12M SLT use unweighted Ns: youth = 407/324/294; young adults = 1,126/801/769; adults 25+ = 1,865/1,440/1,362W1/W2/W3 P30D SLT use unweighted Ns: youth = 198/141/124; young adults = 640/539/503; adults 25+ = 1,379/1,126/1,072W1/W2/W3 daily P30D SLT use unweighted Ns: youth = 47/29/26; young adults = 262/214/190; adults 25+ = 818/642/601 X-axis shows four categories of SLT use (ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D). Y-axis shows weighted percentages of W1, W2, and W3 users. Sample analyzed includes all W1, W2, and W3 respondents at each wave. All respondents with data at one wave are included in the sample for that wave's estimate and do not need to have complete data at all three waves. The PATH Study cross-sectional (W1) or single-wave weights (W2 and W3) were used to calculate estimates at each wave. Ever SLT use is defined as having ever used SLT, even once or twice in lifetime. P12M SLT use is defined as any SLT use within the past 12 months. P30D SLT use is defined as any SLT use within the past 30 days. Daily P30D SLT use is defined as use of SLT on all 30 of the past 30 days. All use definitions refer to any use that includes exclusive or polytobacco use of SLT.

a denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 and W2

b denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 and W3

c denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W2 and W3

The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

In addition, we analyzed cross-sectional use of pouched snus only, other smokeless tobacco, or both at each wave among P30D SLT users (Supplemental Table 1). In all three age groups, among P30D users, the majority were exclusive other SLT users (W1-W3 ranges for youth: 69.3%−71.5%; young adults: 63.7%−72.2%; older adults: 77.3%−85.9%). Among young adult P30D SLT users, use of both types of SLT increased from 18.4% (95% CI: 15.3–22.1) at W1 to 29.5% (95% CI: 25.3–34.1) at W2 and 26.4% (95% CI: 22.3–30.9) at W3. Among adult 25+ P30D SLT users, other smokeless use decreased between W1 and W2 from 85.9% (95% CI: 83.6–87.9) at W1 to 77.3% (95% CI: 73.9–80.3) at W2, while use of both SLT types increased between the two waves (6.8% [95% CI: 5.3–8.6] at W1 to 18.2% [95% CI: 15.3–21.6] at W2). See Supplemental Table 1 for further details.

Longitudinal Weighted W1-W2-W3 Pathways

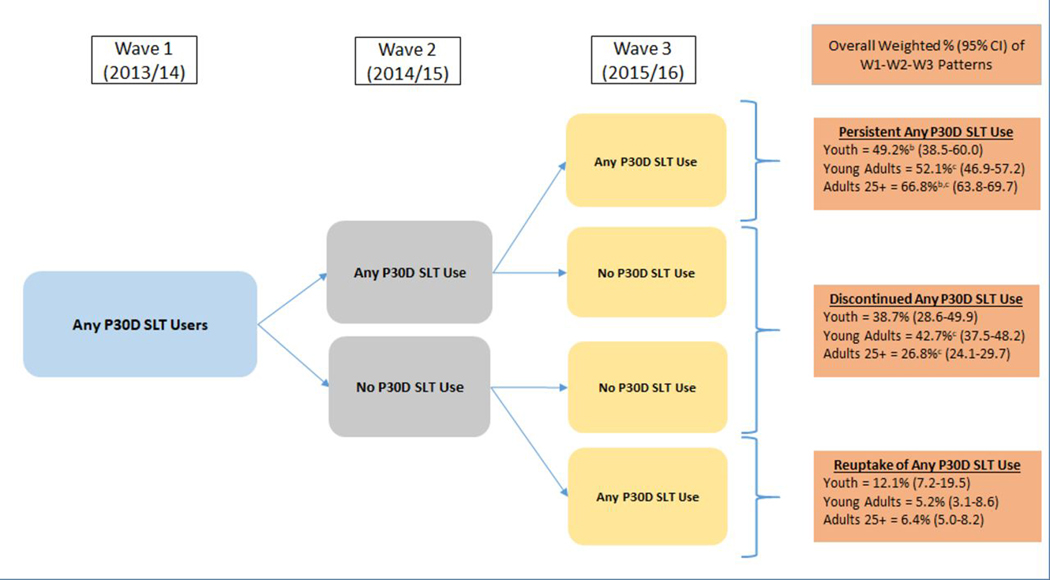

Among any P30D SLT users at W1

At W1 1.5% (95% CI: 1.2–1.8) of youth, 5.1% (95% CI: 4.6–5.7) of young adults, and 2.9% (95% CI: 2.7–3.2) of adults 25+ were P30D SLT users (Figure 2). Figure 2 presents three-wave P30D use and nonuse pathways among W1 P30D SLT users (Aim 2). Persistent P30D SLT use was highest among adults 25+ (66.8% [95% CI: 63.8–69.7]), compared to young adults (52.1%[95% CI: 46.9–57.2]) and youth (49.2% [95% CI: 38.5–60.0]). Discontinued P30D SLT use was higher among young adults (42.7%[95% CI: 37.5–48.2]) compared to adults 25+ (26.8%[95% CI: 24.1–29.7]). Overall, persistent SLT use across W1, W2, and W3 was the most common pathway across all three age groups.

Figure 2:

Patterns of W1–W2–W3 persistent any P30D SLT use, discontinued any P30D SLT use and reuptake of any P30D SLT use among W1 any P30D SLT users.

Abbreviations: W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3; P30D = past 30-day; SLT = smokeless tobacco; CI = confidence interval W1 any P30D SLT use weighted percentages (95% CI) out of total U.S. population: youth (ages 12-17) = 1.5% (1.2-1.8); young adults (ages 18-14) = 5.1% (4.6-5.7); adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) = 2.9% (2.7-3.2) Analysis included W1 youth, young adults, and adults 25+ P30D SLT users with data at all three waves. Respondent age was calculated based on age at W1. W3 longitudinal (all-waves) weights were used to calculate estimates. These rates vary slightly from those reported in Figure 1 or Supplemental Table 1 because this analytic sample in Figure 2 includes only those with data at each of the three waves to examine weighted longitudinal use and non-use pathways. Any P30D SLT use was defined as any SLT use within the past 30 days. Respondent could be missing data on other P30D product use and still be categorized into the following three groups:1) Persistent any P30D SLT use: Defined as exclusive or SLT polytobacco use at W2 and W3.2) Discontinued any P30D SLT use: Defined as any non-SLT tobacco use or no tobacco use at either W2 and W3 or just W3.3) Reuptake of any P30D SLT use: Defined as discontinued SLT use at W2 and any SLT use at W3.

a denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between youth and young adults

b denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between youth and adults 25+

c denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between young adults and adults 25+

The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% CIs. Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Among P30D exclusive SLT users, P30D SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS, and P30D SLT polytobacco users w/o CIGS at W1

Overall, youth and young adults were more likely to be users of SLT and cigarettes, while adults 25+ were more likely to be exclusive SLT users (Supplemental Figure 2 footnote). Among W1 youth and young adult P30D SLT users, 41.5% (95% CI: 33.2–50.3) of youth and 65.0% (95% CI: 61.0–68.9) of young adults were P30D SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS, followed by P30D exclusive SLT users (youth, 33.6% [95% CI: 25.7–42.6]; young adults, 21.9% [95% CI: 18.6–25.6]) and P30D SLT polytobacco users w/o CIGS (youth, 24.9% [95% CI: 16.7–35.2]; young adults, 13.0% [95% CI: 9.7–17.4]). In contrast, among adults 25+ with P30D SLT use at W1, most were P30D exclusive SLT users (57.3% [95% CI: 54.2–60.5]), followed by P30D SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS (35.6% [95% CI: 32.5–38.8]); only 7.1%(95% CI: 5.4–9.2) were P30D SLT polytobacco users w/o CIGS.

To address Aim 3, described below are mutually exclusive pathways (see conceptual map in Supplemental Figure 2) from Supplemental Tables 2a-c that estimate broad behavioral transitions such as persistent use, tobacco cessation, and relapse in the W1 P30D exclusive SLT users, P30D SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS, and P30D SLT polytobacco users w/o CIGS groups. These are summarized in Table 1. Many youth estimates were flagged due to low reliability, which are presented in Table 1 but not discussed.

Table 1:

Transitions in P30D Product Use at W2 and W3 Among W1 P30D SLT Users.

| Youth | Young Adults | Adults 25+ | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 Exclusive SLT Use | W1 SLT PTU w/CIG | W1 SLT PTU w/o CIG | W1 Exclusive SLT Use | W1 SLT PTU w/CIG | W1 SLT PTU w/o CIG | W1 Exclusive SLT Use | W1 SLT PTU w/CIG | W1 SLT PTU w/o CIG | ||||||||||

| Mutually Exclusive Pathways | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI |

| Persistent SLT use type at all waves Continuing the same W1 use type (exclusive, PTU w/CIGS, or PTU w/o CIGS) at each wave | 31.0† | (19.3–45.8) | 37.2c | (24.2–52.2) | 9.5†c | (2.2–32.8) | 17.7a | (11.7–25.8) | 32.7a,c | (26.8–39.3) | 14.7†c | (7.4–27.0) | 68.1a,b | (64.2–71.8) | 36.8a,c | (30.7–43.3) | 11.6b,c | (6.3–20.3) |

| SLT use type reuptake The same broad use type (exclusive or PTU) at W1 and W3 (but a different tobacco use at W2) | 0.0 | N/A | 9.4†c | (4.2–19.7) | 36.7†c | (20.2–57.1) | 16.7 | (10.4–25.9) | 10.0c | (6.6–14.8) | 27.7c | (17.7–40.5) | 4.6a | (2.9–7.1) | 10.9a | (8.1–14.5) | 15.3† | (7.2–29.7) |

| SLT use type transition Transition from W1 exclusive use to PTU by W3, or transition from W1 PTU to exclusive use by W3 (without discontinuing all tobacco use at W2) | 34.0†a,b | (21.8–48.8) | 5.2†a | (1.7–14.9) | 9.7†b | (3.1–26.8) | 35.5a,b | (24.7–48.0) | 9.4a | (6.3–13.8) | 13.3†b | (7.0–23.9) | 8.6b | (6.5–11.2) | 7.7c | (5.0–11.7) | 34.3b,c | (21.2–50.3) |

| Switch or discontinue SLT use, but continue other tobacco use W1 exclusive user who switches to another tobacco product by W3 or W1 polytobacco user that discontinues SLT use by W3 but uses another tobacco product (without discontinuing all tobacco use at W2) | 9.5†a | (2.8–28.2) | 32.8a | (21.8–46.0) | 25.3† | (10.6–49.1) | 4.4†a,b | (1.9–10.2) | 40.6a,c | (34.1–47.5) | 21.2b,c | (11.7–35.5) | 1.6†a,b | (0.8–3.5) | 37.5a,c | (32.5–42.7) | 14.1b,c | (7.9–23.8) |

| Tobacco use reuptake W1 users who discontinue all tobacco use at W2 and use again at W3 | 8.0† | (2.4–23.2) | 4.6† | (1.0–18.5) | 9.7† | (3.0–27.2) | 7.3† | (2.9–17.1) | 1.9† | (0.7–4.9) | 3.1† | (0.4–20.1) | 5.7a | (3.7–8.7) | 0.2†a | (0.0–1.6) | 1.2† | (0.2–8.9) |

| Discontinue all tobacco use W1 users who discontinue all tobacco use at either W2 and W3 or just W3 | 17.5† | (7.8–34.6) | 11.0† | (4.5–24.3) | 9.0† | (2.8–25.8) | 18.4a | (10.7–29.9) | 5.3a | (3.1–9.1) | 19.9† | (10.6–34.5) | 11.4 | (8.9–14.4) | 7.0c | (4.6–10.5) | 23.5c | (13.6–37.3) |

Notes:

Abbreviations: P30D = past 30-day; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3; W1 = Wave 1; SLT = smokeless tobacco; CI = confidence interval; polytobacco use = PTU; w/ = with; w/o = without; CIGS = cigarettes; N/A = not applicable

Analysis included youth (ages 12–17), young adult (ages 18–24), and adult 25+ (ages 25 and older) W1 P30D SLT users with data at all three waves. Respondent age was calculated based on age at W1. W3 longitudinal (all-waves) weights were used to calculate estimates. All tobacco use is defined as P30D use. Use type refers to exclusive use, PTU w/CIG, or PTU w/o CIG.

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 Exclusive SLT Use and W1 SLT PTU w/CIG

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 Exclusive SLT Use and W1 SLT PTU w/o CIG

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 SLT PTU w/CIG and W1 SLT PTU w/o CIG

The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% CIs.

Estimate should be interpreted with caution because it has low statistical precision. It is based on a denominator sample size of less than 50, or the coefficient of variation of the estimate or its complement is larger than 30%.

Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Among Young Adults.

As shown in Table 1, discontinued all tobacco use was higher among W1 exclusive P30D SLT users (18.4% [95% CI: 10.7– 29.9]) compared to W1 P30D SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS (5.3% [95% CI: 3.1– 9.1]).Similarly, transition to SLT PTU among W1 exclusive P30D SLT users was higher (35.5%[95% CI: 24.7–48.0]) than transition to exclusive SLT use among W1 P30D SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS (9.4% [95% CI: 6.3– 13.8]). Persistent use was higher among SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS (32.7% [95% CI: 26.8–39.3]) than exclusive SLT users (17.7%[95% CI: 11.7–25.8]).

Among Adults 25+.

Discontinued all tobacco use was higher among W1 P30D SLT polytobacco users w/o CIGS (23.5% [95% CI: 13.6– 37.3]) compared to W1 exclusive P30D SLT users (11.4% [95% CI: 8.9– 14.4]). Persistent use was highest among W1 exclusive SLT users (68.1% [95% CI: 64.2–71.8]) compared to SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS (36.8% [95% CI: 30.7–43.3]) and W1 P30D SLT polytobacco users w/o CIGS (11.6% [95% CI: 6.3– 20.3]). Transition to exclusive SLT use among W1 P30D SLT polytobacco users w/o CIGS (34.3% [95% CI: 21.2– 50.3]) was higher compared to W1 P30D SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS (7.7% [95% CI: 5.0– 11.7]) and was also higher than transition to SLT PTU among W1 exclusive P30D SLT users (8.6%[95% CI: 6.5–11.2]).

DISCUSSION

This study presents a longitudinal analysis of SLT product use in a nationally representative cohort of youth and adults from 2013–2016. Limited data were previously available on within-person transitions among SLT users. Consistent with other studies,11,12,15 SLT use across the three waves was most common among young adults (18–24 years), compared to the other two age groups. The prevalence of P12M and P30D use among young adults was almost double the prevalence among adults 25+ and almost three times higher than the prevalence among youth. This pattern is consistent with other U.S. population estimates that show young adults have the highest current SLT use compared to other age groups (3.2% among those ages 18–24 versus 2.7% among 25- to 44-year-olds, 2.1% among 45- to 64-year-olds, and 1.2% among those ages 65 and older).22 Cross-sectional SLT ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D use were relatively stable across all three waves in all age groups, which is similar to other national studies showing stable SLT use rates among adults and youth since 200011,23 and more recently between 2014 and 2016.22,24-26 In addition, across all three waves, SLT use was most common among men, which is consistent with other studies.24,27

Longitudinal patterns showed that nearly half or more W1 P30D SLT users were persistent users across the three waves for all age groups (49.2% of youth, 52.1% of young adults, and 66.8% of adults 25+ continued using across all three waves), suggesting that SLT use is relatively stable over time. More youth and young adults had patterns of discontinued SLT use compared to adults 25+. These patterns were similar to those for cigarette smoking as reported by Taylor et al.,28 where most W1 P30D cigarette smokers continued to smoke cigarettes across all three waves (among W1 P30D cigarette users, 60.4% of youth, 68.1% of young adults, and 82.3% of adults 25+ continued through W3), and more youth and young adults discontinued cigarette use by W3 compared to adults 25+. In contrast, these transition patterns are different from other non-cigarette tobacco products such as hookah, ENDS, and cigars that show high rates of discontinuing product use as reported by Sharma et al.,29 Stanton et al.,30 and Edwards et al.31 While most studies have reported on exclusive SLT use, dual use of cigarettes and SLT, and the transitions between the two,11,13,14,32,33 our analysis examined SLT polytobacco use with and without cigarettes because of the growing number of tobacco products that are available on the U.S. market. Our findings showed higher prevalence of SLT polytobacco use w/CIGS among youth and young adults compared to SLT polytobacco use w/o CIGS and exclusive SLT use. Conversely, most adult 25+P30D SLT users were exclusive SLT users.

Distinct longitudinal patterns were observed for exclusive SLT and SLT polytobacco use with and without cigarettes and across age groups. Rates of persistent exclusive SLT use were notably higher among adults 25+, which is consistent with other national studies.13,14,34 In contrast, transition to SLT polytobacco use was a common pathway among young adult exclusive SLT users. Results suggest that young adult exclusive SLT users are likely to transition to SLT polytobacco use and that the SLT plus cigarette combination is more stable than SLT with other noncigarette tobacco use. This pattern of polytobacco use, predominately with cigarettes, among young adults is reported in analyses looking at polytobacco use transitions among ENDS, hookah, and cigars.29–31 Youth and young adults may be using tobacco products with cigarettes consistently rather than experimenting with tobacco products, which may contribute to nicotine dependence and impede cessation efforts.23,35,36

Another notable pathway was discontinuing SLT but continuing other tobacco use among W1 SLT polytobacco users w/CIGS compared to SLT polytobacco users w/o CIGS, particularly among adults 25+. Even though high rates of discontinued SLT use are found among those with SLT polytobacco use w/CIGS, it is unclear if users actually stopped using SLT or if they used the product infrequently and may not have used it in the 30 days before the survey. However, it is noteworthy that those who discontinue SLT may be continuing cigarette use.14,37

Limitations

Study limitations include use of self-reported data, which are subject to recall bias. Small sample sizes in some groups such as youth exclusive SLT users and polytobacco users, especially among SLT w/o CIGS users, limited meaningful interpretations of the pathways. In addition, this report defined discontinued use as no P30D use, without any consideration of intent to quit, which may have overestimated rates of discontinued use and may not represent those who discontinue for extended periods of time and does not account for intermittent users. This study also did not explore longitudinal transition patterns separately by SLT product type (traditional smokeless chew users versus snus pouch users). Future research may explore pathways by types of SLT and examine correlates that predict these unique patterns among exclusive and SLT polytobacco users.

Summary and Implications

This report showed higher persistent use of SLT with cigarette compared to SLT with noncigarette polytobacco use. This may be driven by motivations to transition away from combustible tobacco or to use SLT to circumvent smoke-free policies that restrict users from smoking indoors and also to cope with withdrawal symptoms due to nicotine dependence.33,38 Future work may help to better understand why some SLT users discontinue using the product while others are persistently using it. These results also show that among adults 25+, more SLT with noncigarette polytobacco users became exclusive SLT users compared to SLT with cigarette polytobacco users by W3. These findings highlight the importance of design and promotion of cessation campaigns for SLT use, including cigarette use. Future researchers could also examine how transitions differ by risk-taking and non-risk-taking behaviors particularly among youth.

Supplementary Material

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

Little is known about how SLT use patterns are changing with the growing tobacco marketplace in the U.S.

Longitudinal patterns showed that among W1 P30D SLT users ,nearly half of youth, more than half of young adults, and two thirds of adults 25+ were persistent SLT at all three waves, suggesting SLT use is relatively stable.

While persistent exclusive SLT use is common among adults 25+, transition to SLT polytobacco use was common among youth and young adult exclusive SLT users.

The SLT and cigarette combination is more stable overtime than SLT with other noncigarette tobacco use.

Exploring longitudinal transitions of exclusive and SLT polytobacco use will provide better understanding of product transitions that will allow researchers to determine the population-level health impact of these product.

Footnotes

Disclaimer:The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Financial disclosure:Wilson Compton reports long-term stock holdings in General Electric Company, 3M Company, and Pfizer Incorporated, unrelated to this manuscript.No financial disclosures were reported by the other authors of this paper.

Funding: This manuscript is supported with Federal funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Center for Tobacco Products, Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, under a contract to Westat (Contract No. HHSN271201100027C).

References

- 1.Food and Drug Administration (HHS). Smokeless Tobacco Products, Including Dip, Snuff, Snus, and Chewing Tobacco. 2018; https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ProductsIngredientsComponents/ucm482582.htm. Accessed 11/16/18.

- 2.Popova L, Ling PM. Alternative tobacco product use and smoking cessation: a national study. American journal of public health. 2013;103(5):923–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, et al. Flavored tobacco product use among US youth aged 12–17 years, 2013–2014. Jama. 2015;314(17):1871–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corey CG, Ambrose BK, Apelberg BJ, King BA. Flavored tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(38):1066–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mejia AB, Ling PM. Tobacco industry consumer research on smokeless tobacco users and product development. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(1):78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver AJ, Jensen JA, Vogel RI, Anderson AJ, Hatsukami DK. Flavored and nonflavored smokeless tobacco products: rate, pattern of use, and effects. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;15(1):88–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Canceer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smokeless tobacco and public health: a global perspective. Bethesda, MD: U.S: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute: NIH Publication No; 14–7983; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delnevo CD, Wackowski OA, Giovenco DP, Manderski MTB, Hrywna M, Ling PM. Examining market trends in the United States smokeless tobacco use: 2005–2011. Tobacco control. 2014;23(2):107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilljam H, Galanti MR. Role of snus (oral moist snuff) in smoking cessation and smoking reduction in Sweden. Addiction. 2003;98(9):1183–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014:943. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang JT, Levy DT, Meza R. Trends and Factors Related to Smokeless Tobacco Use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(8):1740–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipari RN, Horn SLV. Trends in smokeless tobacco use and initiation: 2002 to 2014. The CBHSQ Report: May 31, 2017 Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tam J, Day HR, Rostron BL, Apelberg BJ. A systematic review of transitions between cigarette and smokeless tobacco product use in the United States. BMC public health. 2015;15(1):258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sung H-Y, Wang Y, Yao T, Lightwood J, Max W. Polytobacco use of cigarettes, cigars, chewing tobacco, and snuff among US adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;18(5):817–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Y-C, Rostron BL, Day HR, et al. Patterns of Use of Smokeless Tobacco in US Adults, 2013–2014. American Journal of Public Health. 2017(0):e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Public Law 111–31. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tobacco control. 2016:tobaccocontrol-2016–052934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tourangeau R, Yan T, Sun H, Hyland A, Stanton CA. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) reliability and validity study: selected reliability and validity estimates. Tobacco control. 2018:tobaccocontrol-2018–054561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy PJ. Pseudoreplication: further evaluation and applications of the balanced half-sample technique. 1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Judkins DR. Fay’s method for variance estimation. Journal of Official Statistics. 1990;6(3):223. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips E, Wang TW, Husten CG, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(44):1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arrazola RA, Kuiper NM, Dube SR. Patterns of current use of tobacco products among US high school students for 2000–2012—findings from the National Youth Tobacco Survey. Journal of adolescent health. 2014;54(1):54–60. e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu S, Neff L, Agaku I, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults-United States, 2013– 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(27):685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu S, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students-United States, 2011–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(23):597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh T, Arrazola R, Corey C, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students--United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A. Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor KA, Sharma E, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco cigarette use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: Findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma E, Bansal-Travers M, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco hookah use among youth, young adults, and adults in the United States: Findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s155–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanton CA, Sharma E, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal transitions of exclusive and polytobacco electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use among youth, young adults, and adults in the United States: Findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards KC, Sharma E, Halenar MJ, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco cigar use among youth, young adults, and adults in the United States: Findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agaku IT, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Vardavas CI, Connolly G. Predictors and patterns of cigarette and smokeless tobacco use among adolescents in 32 countries, 2007–2011. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54(1):47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalkhoran S, Grana RA, Neilands TB, Ling PM. Dual use of smokeless tobacco or e-cigarettes with cigarettes and cessation. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(2):277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu Q, Vaughn MG, Wu L-T, Heath AC. Psychiatric correlates of snuff and chewing tobacco use. PloS one. 2014;9(12):e113196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. Concurrent use of tobacco products by California adolescents. Preventive medicine. 2003;36(5):575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timberlake DS. A latent class analysis of nicotine-dependence criteria and use of alternate tobacco. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2008;69(5):709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufman AR, Land S, Parascandola M, Augustson E, Backinger CL. Tobacco use transitions in the United States: The national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Preventive medicine. 2015;81:251–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.