Abstract

Background

To determine patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) which may be suitable for incorporation into the Australian Cystic Fibrosis Data Registry (ACFDR) by identifying PROMs administered in adult and paediatric cystic fibrosis (CF) populations in the last decade.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Cochrane Library databases for studies published between January 2009 and February 2019 describing the use of PROMs to measure health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in adult and paediatric patients with CF. Validation studies, observational studies and qualitative studies were included. The search was conducted on 13 February 2019. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments Risk of Bias Checklist was used to assess the methodological quality of included studies.

Results

Twenty-seven different PROMs were identified. The most commonly used PROMs were designed specifically for CF. Equal numbers of studies were conducted on adult (32%, n=31), paediatric (35%, n=34) and both (27%, n=26) populations. No PROMs were used within a clinical registry setting previously. The two most widely used PROMs, the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire—Revised (CFQ-R) and the Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (CFQoL), demonstrated good psychometric properties and acceptability in English-speaking populations.

Discussion

We found that although PROMs are widely used in CF, there is a lack of reporting on the efficacy of methods and timepoints of administration. We identified the CFQ-R and CFQoL as the most suitable for incorporation in the ACFDR as they captured significant effects of CF on HRQoL and were reliable and valid in CF populations. These PROMs will be used in a further qualitative study assessing patients’ with CF and clinicians’ perspectives toward the acceptability and feasibility of incorporating a PROM in the ACFDR.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019126931.

Keywords: public health, cystic fibrosis, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

As per our knowledge, this is the first systematic review evaluating patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in adult and paediatric cystic fibrosis (CF) populations.

This review involves a rigorous and extensive search of medical databases using clearly defined inclusion criteria and distinctly outlines how items will be selected and abstracted.

The study assesses the most relevant and acceptable PROM for the context of a CF clinical registry.

A limitation of this study is that the search was not conducted outside of medical databases, therefore may not capture studies examining PROM use in CF that are not published in peer-reviewed journals.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) has undergone significant changes in the last few decades. In the mid-1900s, the majority of patients with CF did not survive beyond infancy. Now, over half of patients are adults1 and life expectancy exceeds 40 in most developed countries.1 The changing demographics of CF has led to new challenges in both disease management and clinical research. Treatment burden has increased2 such that treatments currently require 2–4 hours a day.3 The growing adult population encounters more difficulties balancing symptom and treatment burden of the disease with work, education or family demands.4 5 Therefore, there is an increasing requirement to examine and manage psychosocial impacts of CF.3 Another challenge is posed by the relative healthiness of the modern CF population resulting in traditional endpoints in clinical trials, such as forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and frequency of pulmonary exacerbations, having reduced sensitivity.6

A possible solution to these challenges is to monitor and collect data on health-related quality of life (HRQoL).7 HRQoL is ‘an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’.8 It encompasses physical health, social networks and relationships, psychological health and functional capacity.8 As HRQoL is subjective, it can be described using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).9 PROMs are standardised sets of questions completed by patients without clinician interpretation.9 PROMs have been used in a range of settings, from enhancing clinician–patient interaction to supporting health policy creation and economic analysis.10 They are widely used in research; in observational studies to describe the impact of a disease on daily functioning, as tools for cost analysis of medical interventions2 and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have recommended HRQoL measures be used as outcomes in clinical trials.5

Australian Cystic Fibrosis Data Registry (ACFDR)

The ACFDR has been collecting data on Australian adults and children diagnosed with CF since 1998. In 2017, the ACFDR held records of 3151 patients,11 estimated to be over 90% of Australia’s CF population.4 The registry collects information on patients’ demographics, social functioning, physical health, treatments and mortality. In addition to increasing awareness about Australia’s CF population, the ACFDR has supported interventional and observational research and economic analysis.12 The ACFDR enables national and international benchmarking,12 which has transformed models of care worldwide.4

PROMs evaluating HRQoL have been incorporated in Australian and international clinical registries.13–15 In the USA, PROM information is used to support observational studies that assess the association between patient demographics, disease burden and HRQoL.16 In Sweden, the National Rheumatology Registry enters its PROM data into a database to which patients and clinicians have access, so that patients are empowered to monitor their HRQoL and shared decision-making is enhanced.15 In Australia, PROMs evaluating HRQoL are currently incorporated in a number of state and national registries.17 Information is used to monitor long-term quality-of-life outcomes of treatments and complications,17 to enable clinicians and health services to benchmark outcomes and ensure patient safety,14 and to influence changes in clinical practice.14

Integration of a PROM evaluating HRQoL into the ACFDR will reinforce the patient voice in data collection. PROMs in the ACFDR have the potential to be used for periodic review of aggregate HRQoL over time; to inform quality improvement for health services and clinicians; and for outcome measurement in registry-related clinical trials.10 In order to fulfil these functions, any PROM selected for integration must be comprehensive in capturing all effects of CF on HRQoL. It must also have demonstrated good psychometric properties, be feasible to incorporate in ACFDR data collection and be acceptable to patients.

Aims

The primary aim of this review was to identify PROMs used in adult and paediatric CF populations, to determine any that may be suitable for incorporation into the ACFDR. Secondary aims were to examine:

Contexts in which PROMs are currently being used in CF (eg, study design and setting).

Methods of administration of PROMs (eg, paper survey, electronic, interview and use of proxy respondents).

Assessed or stated psychometric properties of PROMs (eg, reliability, validity and responsiveness).

Acceptability of PROMs in adult and paediatric patient populations.

Methods

A protocol for this systematic review was created following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.18

Eligibility and inclusion criteria are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) Research Strategy for systematic review

| PICO | Description |

| Population | Adults and children with diagnosed CF. |

| Intervention | Articles describing PROMs used to assess health-related quality of life in CF. |

| Articles describing both generic and disease-specific measures will be included. | |

| Comparison | Studies without a comparator will be considered for inclusion. |

| Outcome | Primary outcome measure is:

|

Secondary outcome measures are:

|

CF, cystic fibrosis; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures.

Inclusion criteria

Articles were included according to the following criteria:

Study participants of all ages with a prior diagnosis of CF.

Inpatients and outpatients.

Study designs including quantitative (eg, cohort, longitudinal, prospective, retrospective and validation) and qualitative studies (eg, ethnography and case report).

Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded according to the following criteria:

Published before January 2009.

No article available in the English language.

Conference abstracts.

Editorials and reviews.

Randomised control trials (RCT), as the same PROM was used for all and they provided limited additional information on secondary outcomes.

Reviewers searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Cochrane Library databases on 13 February 2019. The search strategy was adapted to each database and included keywords: ‘patient reported outcome’ OR ‘patient reported outcome measure’ OR ‘self-report*’ OR ‘questionnaire’ OR ‘scale’ OR ‘perception’ OR ‘quality of life’ OR ‘QOL’ AND ‘cystic fibrosis.’ The search was restricted to English language, humans and last 10 years. Online supplemental file 1 describes the search strategy for each database.

bmjopen-2019-033867supp001.pdf (180.1KB, pdf)

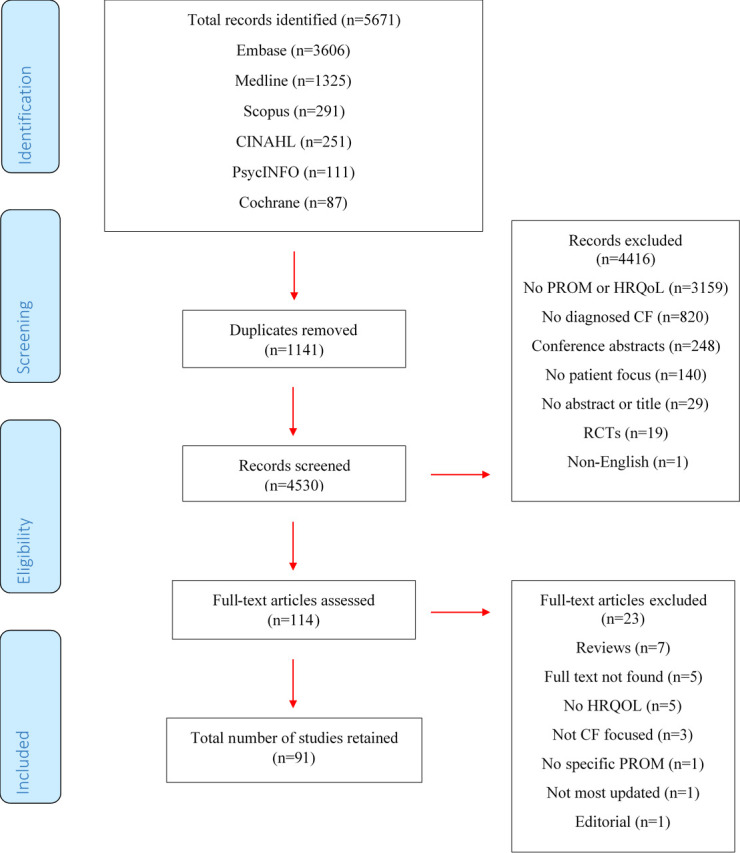

Initial screening involved a reviewer reading titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the search. Any studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed. Full texts of remaining studies were then read one author. Another author reviewed each stage of study selection. A number of studies at each stage of the search were recorded using the PRISMA flow diagram.

A data extraction form was constructed to summarise selected studies in line with the outcomes of the systematic review. Information extracted included: type of study, mean age of participants, setting PROM(s) administered, method of administration, timepoints administered PROM(s) used, type of PROM(s), psychometric properties of PROM(s) and acceptability of PROM(s) to patients.

The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) Risk of Bias Checklist was used to assess methodological quality of included studies. This tool was chosen as it was specifically created for studies using PROMs.19 One reviewer appraised studies using the tool. Items were rated on a 4-point scale denoted as very good, adequate, doubtful or inadequate. The results were summarised into a table presenting the lowest score for each property.19

A descriptive synthesis of results was undertaken, organised thematically by type of PROM and assessing context, administration, acceptability and reliability of each measure. A meta-analysis was not performed as included studies assess different outcomes.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Search results

The search yielded 5671 results. A number at each stage is summarised in figure 1. A final number of 91 studies were included in the review. The data extraction table is presented in online supplemental file 2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Study Identification and SelectionPROM: Patient Reported Outcome MeasureHRQoL: Health-related Quality of LIfeCF: Cystic FibrosisRCTs: Randomised Controlled Trials

bmjopen-2019-033867supp002.pdf (150.8KB, pdf)

Contexts in which PROMs were used

A large proportion (80%, n=73) of studies identified were of observational study design. Validation studies were the next most frequent, making up 15% (n=14) of all studies. The search also identified two non-RCTs, two qualitative studies and one study describing development of a PROM. Similar numbers of studies were conducted on adults (34%, n=31), children (37%, n=34) or both (29%, n=26) age groups.

Most studies recruited patients from a CF outpatient clinic (61%, n=56). Other studies used patient populations from: RCT data (8%, n=7), inpatients (7%, n=6), longitudinal cohort study data (5%, n=5) and national databases (4%, n=4). No study was conducted using clinical registry data. In 48% (n=44) of studies, PROM instruments were used in cross-sectional observational studies to evaluate whether there was an association between HRQoL and physical factors (eg, sleep and physical fitness), psychological factors (eg, self-esteem and illness perception), social factors (eg, stigma and employment status) or demographic factors (eg, age and gender). Other reasons for using PROMs were to assess HRQoL in a population (18%, n=16) or validate PROMs (18%, n=16).

Mode and method of administration

PROMs were commonly self-reported on paper in clinic for 19% (n=17) of studies. Many studies (14%, n=13) used multiple methods of administration, for example, paper and interview. Less commonly, data were collected using electronic methods for 8% (n=7) of studies. Many studies (55%, n=50) did not state mode or method of PROM administration.

For 43 studies conducted on young children below 13 years of age, the most common method of administration for 33% (n=14) was self-report using instruments specially designed for use in young children. Interviews were used in 28% (n=12) of studies and parents were used as proxy respondents in 23% (n=10) of studies completed on paediatric populations. When studies assessed the degree of agreement between child self-report and parent proxies, they found variable results. While some studies found a high level of agreement in parent–child reports,20 21 others found that parents were better able to report HRQoL in observable domains, such as physical symptoms.22–25 Two studies26 27 noted that parent–child agreement was better for younger children than older.

PROMs were administered once at the beginning of the study for the majority of studies (55%, n=50), which reflects the large proportion of cross-sectional studies. Several PROMs were administered twice (12%, n=11) and 15 (16%) studies applied PROMs longitudinally, between 5 and 12 times. The frequency of longitudinal administration varied from fortnightly28 to 2 yearly.29 Studies did not discuss the benefits of administering PROMs at their chosen frequencies. Dill et al30 applied the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire—Revised (CFQ-R) every 3 months and found individual variation in each domain. This was not seen in a study that administered the EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) every 8 weeks.31 Abbott et al32 applied the Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (CFQoL) to the same patients over 12 years and observed a steady decrease of overall CFQoL Score at 1% per year, which correlated with the decrease in FEV1%.

Acceptability

Two studies assessing patient views towards PROMs found that parent caregivers were satisfied with the questionnaires.33 34 Salek et al3 observed that 76% of patients with CF in their study would be willing to complete the CFQoL at every clinic visit. Overall, as most studies did not report the patient burden of PROMs to their patient populations, this review has found limited information on acceptability of PROMs for patients.

PROMs identified

This review identified 27 different PROMs evaluating HRQoL. These were CF-specific, respiratory-specific, mental health-specific or generic PROMs. Some studies (25%, n=23) used two or more different PROMs. CF-specific PROMs were used more commonly than other types. The most common instrument used was CFQ-R, used in 54% (n=49) of studies.

CF-specific instruments

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of CF-specific PROMs identified in this review.

Table 2.

CF-specific PROMs

| PROM | Studies included | Year developed | Target population | Languages* | Number of items and domains | Psychometric properties |

| Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire—Revised28 35 39–41 48 88 89 | 49 | 2003 | Teen/adult (14+ years) | English | Number of Items: | Reliability: α>0.7 except treatment burden and social functioning domains in some studies Test–retest reliability† >0.6 Validity: known groups validity with FEV1, age and body mass index Ceiling effects: eating disturbances (46.4%), body image (39.6%), digestion (37.2%) |

| Adolescent (12–13 years) | Polish | Adult: 50 | ||||

| Child (6–11 years) | German | Adolescent: 35 | ||||

| Parent (proxy for 6–13 years) | Hungarian | Child: 35 | ||||

| Dutch | Parent: 44 | |||||

| Hindi | Domains: physical, vitality, emotion, social, role/school, body image, treatment burden, health perceptions, weight, respiratory, digestion | |||||

| Portuguese | ||||||

| Spanish | ||||||

| Swedish | ||||||

| Turkish | ||||||

| Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Questionnaire3 29 32 50 53–56 71 79 90 | 14 | 2000 | Adult (14+ years) | English | Adult: 52 | Reliability: α: 0.72–0.95 |

| Polish | Domains: physical, social, treatment, emotional, relationships, career, future, chest symptoms, body image | Test–retest reliability >0.7 | ||||

| Greek | Validity: all domains correlated with FEV2, sensitive to change over time | |||||

| Portuguese | ||||||

| Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire27 58 70 91–94 | 7 | 1997 | Teen/adult (14+ years) | English | Number of Items: | Reliability: α=0.62–0.93 for most domains in adult and child questionnaires |

| Child (6–13 years) | German | Adult: 48 | Validity: some domains correlated with FEV1 | |||

| Parent (proxy for 6–13 years) | Dutch | Adolescent: | ||||

| Portuguese | Child: 35 | |||||

| Parent: 44 | ||||||

| Domains: physical functioning, vitality, emotional state, social limitations, role/school, body image, treatment constraints, embarrassment, eating disturbances, health status, weight, respiratory, digestion | ||||||

| DISABKIDS-CF Module34 59 | 2 | 2013 | Child (8–17 years) | Portuguese | Number of items: 10 | Reliability: α: 0.71–0.76 |

| Parent (proxy for 8–17 years) | Domains: impact, treatment | Validity: good convergent and divergent validity assessed by MTMM | ||||

| Ceiling effects: 27.5% impact domain | ||||||

| CF Symptom Diary60 | 1 | 2009 | All ages | English | Number of items: 16 | Not reported |

| Domains: symptom, emotional impact, activity impact | ||||||

| Cystic Fibrosis Respiratory Symptom Diary26 | 1 | 2018 | CFRSD0–6 (proxy for 0–6 years) | English | Number of items: 17 | Validity: discriminates between sick and well patients with CF |

| CFRSD7–11 (proxy for 7–11 years) | Domains: respiratory signs, CF-related impacts | |||||

| Respiratory Symptoms in CF61 | 1 | 2017 | Adult (18+) | English | Number of items: 4 visual assessment scales | Test–retest reliability† >0.7 for 3/4 items |

| Validity: correlates with Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire—Revised and responsive to changes in health | ||||||

| Cystic Fibrosis Symptom Progression Survey33 | 1 | 2015 | Child (0–15 years, self-report and proxy) | Arabic | Number of items: 10 | Reliability: α=0.76 |

| Validity: content validity demonstrated using factor analysis |

*Languages included in this review.

†Test–retest reliability measured by intraclass correlation coefficient.

CF, cystic fibrosis; CFRSD, Cystic Fibrosis Respiratory Symptom Diary; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; MTMM, multitrait–multimethod matrix; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

CFQ-R was the most commonly used PROM in this review. It is widely used as it includes scales for children (6–11 years), adolescents (12–13 years), teens/adults (14+ years) and parents. This PROM is a revised version of the original CFQ.35 The CFQ was developed in France in 199736 and minor revisions were performed by Wenninger et al37 in 2003 due to inadequate psychometric properties found during validation of the German translation. The CFQ-R has been translated into 36 different languages.2 Gancz et al38 reported that the CFQ-R was generally completed in 10–30 min.

Studies demonstrated generally good psychometric properties of the CFQ-R. When considering only the studies in English, internal consistency evaluated by Cronbach alpha ranged from 0.62 to 0.9335 39–41 for adult and child questionnaires and 0.55–0.75 for parent questionnaires.42 Studies reported that the treatment burden, body image and school functioning domains were exceptions.25 35 39 41 Validity was demonstrated by the association between several CFQ-R domains and clinical parameters, in particular FEV130 35 43–47 and body mass index (BMI).46 47 Longitudinal studies have shown that CFQ-R is sensitive to changes to HRQoL with antibiotic treatment48 or over the course of a year.49 Authors suggested that it could predict survival50 and be a determinant for lung transplantation.51 Content validity was acceptable.25 52

The CFQoL was the second most commonly used PROM. It has only been developed for adult populations. Salek et al3 found an average 9-min completion time and that the majority of patients found the instrument acceptable for completion in every clinic appointment. Studies identified in our search described robust psychometric properties of the CFQoL. Reliability measured by Cronbach alpha ranged from 0.72 to 0.9532 53 for all domains. It was correlated with generic measures, Short Form Survey-36 (SF-36) and UK Sickness Impact Profile (UKSIP),3 32 and Shwachman-Kulczycki Score, a clinician reported outcome measure.54 Discriminant validity has been demonstrated by significantly worse CFQoL Scores in patients with CF than in controls.55 Studies demonstrated correlation between CFQoL domains and FEV1;3 32 56 however, one study did not find a significant correlation.57

Other CF-specific PROMs identified included the CFQ, which was the first CF-specific PROM developed and has child, teen/adult and parent versions.35 Studies demonstrated good internal consistency of most domains,27 58 with the exception of treatment burden domain in all versions, social functioning domain in child and adult and eating and digestion domains in adult and parent versions.27 The DISABKIDS-CF Module, which was developed for children, was used in two studies conducted in Brazil. Good internal consistency was demonstrated34 59 but one study found a ceiling effect and low test–retest reliability.59 Several CF-specific PROMs were developed or initially validated during the last decade. These included the CF Respiratory Symptom Diary (CFRSD),26 CF Symptom Progression Survey,33 CF Symptom Diary60 and the Respiratory Symptoms in CF.61

Respiratory-specific PROMs

Several HRQoL PROMs developed for chronic respiratory conditions were used in CF. These included the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ),61 62 St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ),63 64 the Sinus and Nasal Quality of Life Survey (SN-5),65 66 the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22)67 and the Liverpool Respiratory Symptom Questionnaire (LRSQ).6 The SN-5 and SNOT-22 exclusively assess sinus symptoms.65–67 The other respiratory PROMs, LCQ, SGRQ and LRSQ were originally piloted in patients with asthma68 or chronic cough.69 The LCQ, SGRQ and LRSS demonstrated acceptable reliability6 58 70 and were found to correlate with CFQ-R domains61 62 and lung function tests.6 63 However, two studies found ceiling effects with the LCQ.61 62 Reliability of the SN-5 and SNOT-22 was not assessed, but SNOT-22 demonstrated floor effects67 and the validity of SN-5 has not been assessed in CF.66

Mental health-specific PROMs

The most common mental health-specific PROM identified was the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS), which was used in eight observational studies in Europe and the USA. The instrument was reported to take 15–20 min to complete.71 Studies found good reliability assessed by Cronbach alpha.39 72 Yohannes et al71 found good test–retest reliability and correlation with CFQoL. The HADS was used to show increased anxiety and depression in patients with CF compared with the non-CF population.73 Other HRQoL surveys focused on mental health identified were the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, General Health Questionnaire and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7. Each was used in one study and found to have acceptable reliability;64 74 however, validity was not assessed.

Generic instruments

Table 3 describes the characteristics of generic instruments included in this study.

Table 3.

Generic PROMs

| PROM | Number of studies included | Year developed | Target population | Languages* | Number of items and domains | Psychometric properties |

| EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D)21 31 43 70 75–77 | 7 | 1990 | EuroQol-5 Dimension-3 Level (EQ-5D-3L) (16+) | English | Number of items: 5 | Validity: discriminates between CF and non-CF population Ceiling effects: 44%–67% |

| EuroQol-5 Dimension-5 Level (EQ-5D-5L) (16+) | French | Domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression | ||||

| EuroQoL-5 Dimension-Youth (EQ-5D-Y) (8–15 years, self report and proxy) | German | |||||

| Hungarian | ||||||

| Italian | ||||||

| Spanish | ||||||

| Swedish | ||||||

| Bulgarian | ||||||

| Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory20 22 23 48 86 | 5 | 1998 | Child (8–12 years, self report and proxy) | English Hungarian Persian |

Number of items: 23 | Reliability: α=0.68–0.93 |

| Domains: physical, emotional, school, social | Validity: discriminates between CF and asthma or non-CF population | |||||

| Short Form Survey-36 (SF-36)50 63 64 95 | 4 | 1990 | Adult (14+) | English German Italian Polish |

Number of items: 36 | Known groups validity with age and time after lung transplant Ceiling effects up to 67.7% in some domains |

| Domains: physical functioning, role—physical, role—emotional, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, mental health | ||||||

| UK Sickness Impact Profile3 | 1 | 1975 | Adult (18+) | English | Number of items: 136 | Reliability: α=0.87–0.9 Test–retest reliability† 0.57–0.84 Convergent validity with Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| Domains: sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care, social interaction, alertness behaviour, emotional behaviour, communication | ||||||

| World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale54 | 1 | 1996 | Adult (16+) | Portuguese | Number of items: 26 | Not reported |

| Domains: physical health, psychological, social relationships, environment | ||||||

| Single Item Scale71 | 1 | 2011 | Adult (18+) | English | Number of items: 1 | Test–retest reliability† 0.78 |

| Quality of Life Profile for the Chronically Ill63 | 1 | 2000 | Adult (18+) | German | Number of items: 40 | Not reported |

| Domains: physical capacity, psychological capacity, social capacity, psychological well-being, social well-being | ||||||

| Core Outcome Measures40 | 1 | 1993 | Adult (16+) | English | Number of items: 34 | Convergent validity with CFQ-R |

| Domains: well-being, symptoms, functioning, risk | ||||||

| KINDL52 | 1 | 1994 | Child (3–17 years) | Turkish | Number of items: 40 | Convergent validity with CFQ-R |

| Domains: psychosocial well-being, physical state, social relationships, functional capacity (76) |

*Languages included in this review.

†Test–retest reliability measured by intraclass correlation coefficient.

CF, cystic fibrosis; CFQ-R, Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire—Revised; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

The most common generic instrument was the EQ-5D Questionnaire, which was developed to enable economic evaluations based on HRQoL Scores. It has five dimensions and includes EuroQol-5 Dimension-3 Level (EQ-5D-3L) version which has three response options, EuroQol-5 Dimension-5 Level (EQ-5D-5L) version which has five response options, and EuroQol-5 Dimension-Youth (EQ-5D-Y) which has been designed for children and adolescents. All three versions of the PROM were used in this review21 31 43 70 75–77 This review found EQ-5D-3L was reliable43 and correlated with CFQ-R.76 EQ-5D-5L distinguished HRQoL differences in CF and non-CF populations75 and was sensitive to change during pulmonary exacerbation.76 However, studies found a large proportion of patients reporting no problems with EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-Y,31 70 demonstrating that the PROMs may not be sensitive in collecting HRQoL data from patients with CF.

A similar finding was observed in the SF-36, which was used in four European studies on adult populations.50 55 63 64 The instrument demonstrated robust reliability with Cronbach alpha of 0.9564 and discriminated between CF and non-CF populations.55 64 However, Abbott et al50 found a high proportion of participants reporting no problems and that the instrument was less sensitive to clinical deterioration than the CFQoL.

The Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) is a generic HRQoL instrument developed for children with paediatric cancers.78 The PedsQL demonstrated good internal consistency,20 discriminant validity comparing asthma and CF and correlated with BMI.48 Other generic HRQoL PROMs described in adult populations were World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF),54 Core Outcome Measures Tool,40 UKSIP,3 KINDL and the Quality of Life Profile for the Chronically Ill.63 These instruments were each used in one observational study. Psychometric properties were not evaluated in included studies.

Risk of bias

The COSMIN Risk of Bias Checklist is designed to critically appraise studies evaluating the reliability or validity of PROMs. A number of studies in this review did not validate instruments for their study population and relied on previous reliability and validity statistics for the PROM used. Therefore, these studies were not critically appraised. The results of critical appraisal are summarised in online supplemental file 3.

bmjopen-2019-033867supp003.pdf (99.6KB, pdf)

Critically appraising articles using the COSMIN Checklist enables reviewers to discern whether psychometric properties have been evaluated using appropriate methodology. From this, reviewers can determine whether the information reported on psychometric properties of PROMs is trustworthy. For example, the second most commonly evaluated property ‘Internal Consistency’ frequently received optimal scores, demonstrating that researchers were in line with COSMIN recommendations and that ‘Internal Consistency’ reported is generally reliable. However, the most commonly reported property ‘Hypothesis Testing for Construct Validity’ received variable scores, demonstrating a lack of reliability in interpreting this statistic.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research

Discussion

Contexts in which PROMs were used

This review identified that PROMs are used in a variety of settings in CF. PROMs were most commonly used in observational studies, where they assessed the impact of physical, psychological, social or demographic variables on HRQoL. This review did not find studies describing implementation of a PROM in a clinical registry or which used clinical registry data.

Some studies were developing PROMs or undertaking validation of new PROMs. This may suggest that existing PROMs are not meeting researchers’ requirements. Limitations of existing PROMs may include the length of commonly used CF-specific PROMs, which could reduce patient compliance and increase data entry burden. Newly developed CF-specific PROMs identified in this study were substantially shorter,33 61 79 demonstrating that researchers require less burdensome CF-specific PROMs. Another limitation may be inadequacy of paediatric measures as currently, no validated PROMs exists to measure data in 0–6 year olds.26 This review identified researchers validating or developing PROMs for younger patient populations.26 33 59

Mode and methods of administration

The mode of administration of the selected PROM will be a major determinant of patient adherence and completion rates.9 Studies in this review used paper based methods most frequently. However, electronic or online administration is reported to have higher patient adherence,9 avoid the need for manual data entry and be more cost effective in the long term than paper methods.80

For paediatric populations, the most common method of administration was self-reporting, using instruments specially designed for use in children. Proxy reporting was uncommon and studies investigating the consistency of parent and child results found that it was better for observable symptoms22–25 and younger children.26 27 Edwards et al26 hypothesised this finding was because parents are more involved in care for younger children and therefore have a better understanding of their HRQoL.

This review demonstrated the advantages of longitudinal PROM collection, as associations between physical and sociodemographic characteristics and quality of life were seen in studies undertaken over a decade,29 32 which were not seen over 12-month or 18-month periods.30 However, where PROMs captured longitudinally, there was a range of frequencies of administration, demonstrating a lack of consensus on the most appropriate time required between PROM administration. Studies generally did not report information on the effectiveness of the frequency of administration in demonstrating changes in HRQoL. Further evaluation of the most useful and acceptable timepoints of administration must be conducted prior to incorporation of a PROM into the ACFDR.

PROMs identified

Our review identified that PROMs developed specifically for CF are more commonly used for patients with CF than generic PROMs. Generic PROMs, which ask about health domains relevant to everyone, have the advantage of applicability across all populations.14 Therefore, they were used to compare different diseases and in cost analysis studies.21 75 CF-specific PROMs include an assessment of CF symptoms that are not relevant in non-CF populations,14 therefore have comparatively limited uses in health policy. However, this review found that CF-specific PROMs are more responsive to changes in health9 and better correlated to clinical parameters22 81 compared with generic PROMs. Significant ceiling effects found using EQ-5D31 or SF-3650 suggest these generic instruments are not capturing problems faced by the CF population. Specific PROMs can, therefore, give more clinically relevant information than generic2 9 and better compare outcomes within CF populations.82

A number of symptom-specific PROMs were identified in our review that focused on respiratory symptoms or mental health. As CF affects all four domains of HRQoL, physical health, psychological health, social relationships and functional capacity, the use of these symptom-specific PROMs will not provide the comprehensive assessment of HRQoL required by the ACFDR. While it is important to assess depression and anxiety in CF, evaluating only these symptoms may give a limited understanding of the effect of CF on overall HRQoL.

Choosing a PROM for the ACFDR

The ACFDR was established to facilitate varying research methodologies and impart accurate information on the current outcomes of Australia’s CF population.4 One of its key functions, providing feedback on outcomes for clinicians and health services, is critical for the ongoing improvement of care.83 The inclusion of CF-specific domains in the chosen tool is, therefore, essential, as these domains will be most directly affected by changes in treatment and will be the most useful information to feedback to clinicians. Similarly, CF symptom information will be relevant for pharmaceutical companies or researchers following up the long-term outcomes of treatment and complications. In addition, ensuring that PROM data captures all domains of HRQoL will enable it to be widely used in research. Therefore, it is most appropriate to include a CF-specific PROM.

After evaluating PROMs based on the predetermined criteria for incorporation into the ACFDR; comprehensiveness, robust psychometric properties, feasibility and acceptability, the CFQ-R and CFQoL come closest to achieving this criteria. They are comprehensive as they include both general and CF-specific domains. This review establishes satisfactory psychometric properties for these two instruments.

A major limitation to incorporating either PROM into the ACFDR is the length of the instruments, which may dissuade patients from participating in data collection or completing the instrument. This poses a difficulty, as a large amount of missing data may cause collection of PROMs to become ineffectual. However, if patients believe that measuring HRQoL is useful to them, they may complete the instrument regardless of its length. At the Duke Cancer Institute in the USA, patients in solid tumour clinics have less than 5% missing data for a survey with median completion time of 11 min.81 Communication of the beneficial outcomes to patients, clinicians and researchers of HRQoL data collection may influence patients to regard completing the instrument as important to them.

Both selected CF PROM Tools are also the oldest specific instruments developed in CF.84 85 There is a possibility of longevity bias if these PROMs are most commonly used in CF because they are well known, rather than superior instruments. Another concern is that as the demographics and outcomes of CF have changed considerably since these instruments were first developed, their relevance to the current population may be limited. In addition, the PROM selected for the ACFDR must also be applicable to future populations, so that registry data collection remains consistent.81 However, both the CFQ-R and CFQoL demonstrated the most robust psychometric properties of all the PROMs and recent studies that used these instruments reported no requirement for modification,28 56 86 87 so it can be concluded they are currently relevant to the CF population.

Limitations of the review

This systematic review has several limitations. Researchers did not conduct a grey literature search, which may have resulted in reduced information extracted on PROMs use in CF registries. However, it may also occur because there is limited reporting on PROM incorporation in CF registries. Researchers excluded RCTs from this review, which limited our results on the extent of PROM use in CF research. Initial searches for this topic identified that RCTs only used the CFQ-R and did not report administration methods or psychometric properties of PROMs. Therefore, we felt that excluding RCTs enabled a focus on observational studies, which have data collection methods more closely resembling clinical registries and included more information on secondary outcomes of this study.

Another limitation is the lack of information identified on the views of patients with CF and caregivers on the relevance of PROMs, their clarity and structure, ease of use and whether completing PROMs was emotionally burdensome. Researchers found very few studies reported data on acceptability, such as response rates, administration time or qualitative perspectives of patients or caregivers on PROMs. Therefore, limited information on that outcome is described in this review. This information is important because symptoms and treatments are already emotionally and physically demanding, therefore a time-consuming and difficult questionnaire should not be imposed on patients. In addition, giving a questionnaire that is meaningful to patients and clinicians is essential to ensure compliance and guarantee complete data collection.

In order to overcome these limitations, researchers will conduct a further feasibility and acceptability study to identify patient and clinician perspectives toward incorporation of either the CFQ-R or CFQoL into the ACFDR.

Conclusion

This review aimed to identify whether existing HRQoL instruments are suitable for incorporation in the registry and to gain an understanding of the use of PROMs in CF. We found that PROMs are widely used in CF, but there is a lack of reporting on methods of administration and timepoints. We have identified two PROMs appropriate for ACFDR that will be used in a further qualitative study of patients with CF and clinicians, to gain their perspectives on the instruments and the feasibility of incorporating a PROM into the ACFDR.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors developed the protocol for this systematic review. IR conducted the screening of studies, data extraction and critical appraisal. RR reviewed each stage of study selection. All authors assisted in the interpretation and write up of results. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Additional data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Quittner AL, Saez-Flores E, Barton JD. The psychological burden of cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2016;22:187–91. 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratjen F, Bell SC, Rowe SM, et al. . Cystic fibrosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015;1:15010. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salek MS, Jones S, Rezaie M, et al. . Do patient-reported outcomes have a role in the management of patients with cystic fibrosis? Front Pharmacol 2012;3:38. 10.3389/fphar.2012.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell SC, Bye PTP, Cooper PJ, et al. . Cystic fibrosis in Australia, 2009: results from a data registry. Med J Aust 2011;195:396–400. 10.5694/mja11.10719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royce FH, Carl JC. Health-related quality of life in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pediatr 2011;23:535–40. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834a7829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trinick R, Southern KW, McNamara PS. Assessing the Liverpool respiratory symptom questionnaire in children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2012;39:899–905. 10.1183/09031936.00070311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elborn JS. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2016;388:2519–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00576-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organisatoin WHOQOL-BREF : introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment: field trial version, December 1996. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackwell LS, Marciel KK, Quittner AL. Utilization of patient-reported outcomes as a step towards collaborative medicine. Paediatr Respir Rev 2013;14:146–51. 10.1016/j.prrv.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams K, Sansoni J, Morris D. Patient-reported outcome measures: literature review. Sydney: Australian Commision for Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruseckaite R, Ahern S, Ranger T, et al. . Australian cystic fibrosis data registry annual report, 2017. Melbourne: Monash University Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahern S, Sims G, Earnest A, et al. . Optimism, opportunities, outcomes: the Australian cystic fibrosis data registry. Intern Med J 2018;48:721–3. 10.1111/imj.13807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devlin N, Appleby J, Buxton M, et al. . Getting the most out of PROMs. London: The King’s Fund, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Victorian Department of Health Collecting patient reported outcomes measures in Victoria consultation paper. Melbourne: Department of Health and Human Services, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson EC, Eftimovska E, Lind C, et al. . Patient reported outcome measures in practice. BMJ 2015;350:g7818 10.1136/bmj.g7818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weitzman ER, Wisk LE, Salimian PK, et al. . Adding patient-reported outcomes to a multisite registry to quantify quality of life and experiences of disease and treatment for youth with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2018;2 10.1186/s41687-017-0025-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson C, Sansoni J, Morris D, et al. . Patient-reported outcome measures: an environmental scan of the Australian healthcare sector. Sydney: Australian Commision on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. . COSMIN checklist manual. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodnár R, Kádár L, Szabó L, et al. . Health related quality of life of children with chronic respiratory conditions. Adv Clin Exp Med 2015;24:487–95. 10.17219/acem/24991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chevreul K, Berg Brigham K, Michel M, et al. . Costs and health-related quality of life of patients with cystic fibrosis and their carers in France. J Cyst Fibros 2015;14:384–91. 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Driscoll KA, Modi AC, Filigno SS, et al. . Quality of life in children with CF: Psychometrics and relations with stress and mealtime behaviors. Pediatr Pulmonol 2015;50:560–7. 10.1002/ppul.23149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kianifar H-R, Bakhshoodeh B, Hebrani P, et al. . Qulaity of life in cystic fibrosis children. Iran J Pediatr 2013;23:149–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kir D, Gupta S, Jolly G, et al. . Health related quality of life in Indian children with cystic fibrosis. Indian Pediatr 2015;52:403–8. 10.1007/s13312-015-0645-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt A, Wenninger K, Niemann N, et al. . Health-related quality of life in children with cystic fibrosis: validation of the German CFQ-R. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:97. 10.1186/1477-7525-7-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards TC, Emerson J, Genatossio A, et al. . Initial development and pilot testing of observer-reported outcomes (ObsROs) for children with cystic fibrosis ages 0-11years. J Cyst Fibros 2018;17:680–6. 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tluczek A, Becker T, Grieve A, et al. . Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: convergent validity with parent-reports and objective measures of pulmonary health. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2013;34:252–61. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182905646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flume PA, Suthoff ED, Kosinski M, et al. . Measuring recovery in health-related quality of life during and after pulmonary exacerbations in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2019;18:737–42. 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbott J, Morton AM, Hurley MA, et al. . Longitudinal impact of demographic and clinical variables on health-related quality of life in cystic fibrosis. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007418. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dill EJ, Dawson R, Sellers DE, et al. . Longitudinal trends in health-related quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. Chest 2013;144:981–9. 10.1378/chest.12-1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solem CT, Vera-Llonch M, Liu S, et al. . Impact of pulmonary exacerbations and lung function on generic health-related quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;14:63. 10.1186/s12955-016-0465-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbott J, Hurley MA, Morton AM, et al. . Longitudinal association between lung function and health-related quality of life in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2013;68:149–54. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norrish C, Norrish M, Fass U, et al. . The cystic fibrosis symptom progression survey (CF-SPS) in Arabic: a tool for monitoring patient’s symptoms. Oman Med J 2015;30:16–25. 10.5001/omj.2015.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serio dos Santos DMdeS, Deon KC, Fegadolli C, et al. . [Cultural adaptation and initial psychometric properties of the DISABKIDS ® - Cystic Fibrosis Module - Brazilian version]. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2013;47:1311–7. 10.1590/S0080-623420130000600009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quittner AL, Sawicki GS, McMullen A, et al. . Erratum to: psychometric evaluation of the cystic fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised in a national, US sample. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1279–90. 10.1007/s11136-011-0091-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henry B, Aussage P, Grosskopf C, et al. . Measuring quality of life in children with cystic fibrosis: the cystic fibrosis questionnaire (CFQ). Qual Life Res 1997;6:657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wenninger K, Aussage P, Wahn U, et al. . The revised German cystic fibrosis questionnaire: validation of a disease-specific health-related quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res 2003;12:77–85. 10.1023/A:1022011704399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gancz DW, Cunha MT, Leone C, et al. . Quality of life amongst adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis: correlations with clinical outcomes. Clinics 2018;73:e427. 10.6061/clinics/2017/e427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliver KN. Longitudinal study of perceived stigma, disclosure, and optimism in adolescents and adults living with cystic fibrosis: measuring the impact on psychological and physical health. Dissertation abstracts international: section B: the sciences and engineering, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Platten MJ, Newman E, Quayle E. Self-esteem and its relationship to mental health and quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2013;20:392–9. 10.1007/s10880-012-9346-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon SL, Duncan CL, Horky SC, et al. . Body satisfaction, nutritional adherence, and quality of life in youth with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2011;46:1085–92. 10.1002/ppul.21477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alpern AN, Brumback LC, Ratjen F, et al. . Initial evaluation of the parent cystic fibrosis questionnaire-revised (CFQ-R) in infants and young children. J Cyst Fibros 2015;14:403–11. 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Acaster S, Pinder B, Mukuria C, et al. . Mapping the EQ-5D index from the cystic fibrosis questionnaire-revised using multiple modelling approaches. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:33. 10.1186/s12955-015-0224-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cronly J, Duff A, Riekert K, et al. . Positive mental health and wellbeing in adults with cystic fibrosis: a cross sectional study. J Psychosom Res 2019;116:125–30. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hochwälder J, Bergsten Brucefors A, Hjelte L. Psychometric evaluation of the Swedish translation of the revised cystic fibrosis questionnaire in adults. Ups J Med Sci 2017;122:61–6. 10.1080/03009734.2016.1225871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawicki GS, Sellers DE, Robinson WM. Associations between illness perceptions and health-related quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Psychosom Res 2011;70:161–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borawska-Kowalczyk U, Sands D. Determinants of health-related quality of life in polish patients with CF - adolescents’ and parents’ perspectives. Dev Period Med 2015;19:127–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Modi AC, Lim CS, Driscoll KA, et al. . Changes in pediatric health-related quality of life in cystic fibrosis after IV antibiotic treatment for pulmonary exacerbations. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2010;17:49–55. 10.1007/s10880-009-9179-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sawicki GS, Rasouliyan L, McMullen AH, et al. . Longitudinal assessment of health-related quality of life in an observational cohort of patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2011;46:36–44. 10.1002/ppul.21325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abbott J, Hart A, Morton AM, et al. . Can health-related quality of life predict survival in adults with cystic fibrosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:54–8. 10.1164/rccm.200802-220OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solé A, Pérez I, Vázquez I, et al. . Patient-Reported symptoms and functioning as indicators of mortality in advanced cystic fibrosis: a new tool for referral and selection for lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016;35:789–94. 10.1016/j.healun.2016.01.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuksel H, Yilmaz O, Dogru D, et al. . Reliability and validity of the cystic fibrosis questionnaire-revised for children and parents in turkey: cross-sectional study. Qual Life Res 2013;22:409–14. 10.1007/s11136-012-0152-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stofa M, Xanthos T, Ekmektzoglou K, et al. . Quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis: the Greek experience. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2016;84:205–11. 10.5603/PiAP.2016.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forte GC, Barni GC, Perin C, et al. . Relationship between clinical variables and health-related quality of life in young adult subjects with cystic fibrosis. Respir Care 2015;60:1459–68. 10.4187/respcare.03665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uchmanowicz I, Jankowska-Polańska B, Rosińczuk J, et al. . Health-related quality of life of patients suffering from cystic fibrosis. Adv Clin Exp Med 2015;24:147–52. 10.17219/acem/38147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomaszek L, Dębska G, Cepuch G, et al. . Evaluation of quality of life predictors in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Heart Lung 2019;48:159–65. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dębska G, Cepuch G, Mazurek H. Quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis depending on the severity of the disease and method of its treatment. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 2014;68:499–503. 10.5604/17322693.1101598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tluczek A, Becker T, Laxova A, et al. . Relationships among health-related quality of life, pulmonary health, and newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Chest 2011;140:170–7. 10.1378/chest.10-1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.dos Santos DMdeSS, Deon KC, Bullinger M, et al. . Validity of the DISABKIDS®-Cystic fibrosis module for Brazilian children and adolescents. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2014;22:819–25. 10.1590/0104-1169.3450.2485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goss CH, Edwards TC, Ramsey BW, et al. . Patient-reported respiratory symptoms in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2009;8:245–52. 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ward N, Stiller K, Rowe H, et al. . The psychometric properties of the Leicester cough questionnaire and respiratory symptoms in CF tool in cystic fibrosis: a preliminary study. J Cyst Fibros 2017;16:425–32. 10.1016/j.jcf.2016.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Del Corral T, Percegona J, López N, et al. . Validity of a Spanish version of the Leicester cough questionnaire in children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Bronconeumol 2016;52:63–9. 10.1016/j.arbres.2015.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ihle F, Zimmermann G, Meis T, et al. . Determinants of quality of life after lung transplantation. Open Transplant J 2015;8:1–7. 10.2174/1874418401508010001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ricotti S, Martinelli V, Caspani P, et al. . Changes in quality of life and functional capacity after lung transplantation: a single-center experience. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2017;87:123–9. 10.4081/monaldi.2017.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xie DX, Wu J, Kelly K, et al. . Evaluating the sinus and nasal quality of life survey in the pediatric cystic fibrosis patient population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017;102:133–7. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chan DK, McNamara S, Park JS, et al. . Sinonasal quality of life in children with cystic fibrosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;142:743–9. 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.0979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kang SH, Meotti CD, Bombardelli K, et al. . Sinonasal characteristics and quality of life by SNOT-22 in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017;274:1873–82. 10.1007/s00405-016-4426-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Powell CVE, McNamara P, Solis A, et al. . A parent completed questionnaire to describe the patterns of wheezing and other respiratory symptoms in infants and preschool children. Arch Dis Child 2002;87:376–9. 10.1136/adc.87.5.376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, et al. . Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester cough questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax 2003;58:339–43. 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eidt-Koch D, Mittendorf T, Greiner W. Cross-sectional validity of the EQ-5D-Y as a generic health outcome instrument in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis in Germany. BMC Pediatr 2009;9:55. 10.1186/1471-2431-9-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yohannes AM, Dodd M, Morris J, et al. . Reliability and validity of a single item measure of quality of life scale for adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:105. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goldbeck L, Besier T, Hinz A, et al. . Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in German patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest 2010;138:929–36. 10.1378/chest.09-2940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olveira C, Sole A, Girón RM, et al. . Depression and anxiety symptoms in Spanish adult patients with cystic fibrosis: associations with health-related quality of life. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016;40:39–46. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Quon BS, Bentham WD, Unutzer J, et al. . Prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety in adults with cystic fibrosis based on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 screening questionnaires. Psychosomatics 2015;56:345–53. 10.1016/j.psym.2014.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Angelis A, Kanavos P, López-Bastida J, et al. . Social and economic costs and health-related quality of life in non-institutionalised patients with cystic fibrosis in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:428. 10.1186/s12913-015-1061-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bradley JM, Blume SW, Balp M-M, et al. . Quality of life and healthcare utilisation in cystic fibrosis: a multicentre study. Eur Respir J 2013;41:571–7. 10.1183/09031936.00224911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chevreul K, Michel M, Brigham KB, et al. . Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis in Europe. Eur J Health Econ 2016;17:7–18. 10.1007/s10198-016-0781-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care 1999;37:126–39. 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Fatoye FA, et al. . Relationship between anxiety, depression, and quality of life in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Respir Care 2012;57:550–6. 10.4187/respcare.01328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Glicklich RE, Dryer NA, Leavy MB. Use of patient-reported outcomes in registries : Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: a user’s guide 2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Backström-Eriksson L, Bergsten-Brucefors A, Hjelte L, et al. . Associations between genetics, medical status, physical exercise and psychological well-being in adults with cystic fibrosis. BMJ Open Respir Res 2016;3:e000141. 10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Australia’s health 2018. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilcox N, McNeil JJ. Clinical quality registries have the potential to drive improvements in the appropriateness of care. Med J Aust 2016;205:S21–6. 10.5694/mja15.00921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gee L, Abbott J, Conway SP, et al. . Development of a disease specific health related quality of life measure for adults and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2000;55:946–54. 10.1136/thorax.55.11.946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Henry B, Aussage P, Grosskopf C, et al. . Development of the cystic fibrosis questionnaire (CFQ) for assessing quality of life in pediatric and adult patients. Qual Life Res 2003;12:63–76. 10.1023/A:1022037320039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vandeleur M, Walter LM, Armstrong DS, et al. . Quality of life and mood in children with cystic fibrosis: associations with sleep quality. J Cyst Fibros 2018;17:811–20. 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cavanaugh K, Read L, Dreyfus J, et al. . Association of poor sleep with behavior and quality of life in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Sleep Biol Rhythms 2016;14:199–204. 10.1007/s41105-015-0044-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Solé A, Olveira C, Pérez I, et al. . Development and electronic validation of the revised cystic fibrosis questionnaire (CFQ-R Teen/Adult): new tool for monitoring psychosocial health in CF. J Cyst Fibros 2018;17:672–9. 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schmidt AM, Jacobsen U, Bregnballe V, et al. . Exercise and quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis: a 12-week intervention study. Physiother Theory Pract 2011;27:548–56. 10.3109/09593985.2010.545102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kelemen L, Lee AL, Button BM, et al. . Pain impacts on quality of life and interferes with treatment in adults with cystic fibrosis. Physiother Res Int 2012;17:132–41. 10.1002/pri.524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aguiar KCA, Marson FAL, Gomez CCS, et al. . Physical performance, quality of life and sexual satisfaction evaluation in adults with cystic fibrosis: an unexplored correlation. Rev Port Pneumol 2017;23:179–92. 10.1016/j.rppnen.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cohen MA, Ribeiro MÂGdO, Ribeiro AF, et al. . Quality of life assessment in patients with cystic fibrosis by means of the cystic fibrosis questionnaire. J Bras Pneumol 2011;37:184–92. 10.1590/s1806-37132011000200008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shoff SM. Nutritional status and quality of life in children with CF aged 9 to 19 years. Pediatr Pulmonol 2014;38:174–6. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tibosch MM, Sintnicolaas CJJCM, Peters JB, et al. . How about your peers? cystic fibrosis questionnaire data from healthy children and adolescents. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:86. 10.1186/1471-2431-11-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Uchmanowicz I, Jankowska-Polańska B, Wleklik M, et al. . Health-related quality of life of patients with cystic fibrosis assessed by the SF-36 questionnaire. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2014;82:10–17. 10.5603/PiAP.2014.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033867supp001.pdf (180.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033867supp002.pdf (150.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033867supp003.pdf (99.6KB, pdf)