Abstract

Objectives

UK exercise referral schemes (ERSs) have been criticised for focusing too much on exercise prescription and not enough on sustainable physical activity (PA) behaviour change. Previously, a theoretically grounded intervention (coproduced PA referral scheme, Co-PARS) was coproduced to support long-term PA behaviour change in individuals with health conditions. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of Co-PARS compared with a usual care ERS and no treatment for increasing cardiorespiratory fitness.

Design

A three-arm quasi-experimental trial.

Setting

Two leisure centres providing (1) Co-PARS, (2) usual exercise referral care and one no-treatment control.

Participants

68 adults with lifestyle-related health conditions (eg, cardiovascular, diabetes, depression) were recruited to co-PARS, usual care or no treatment.

Intervention

16-weeks of PA behaviour change support delivered at 4, 8, 12 and 18 weeks, in addition to the usual care 12-week leisure centre access.

Outcome measures

Cardiorespiratory fitness, vascular health, PA and mental well-being were measured at baseline, 12 weeks and 6 months (PA and mental well-being only). Fitness centre engagement (co-PARS and usual care) and behaviour change consultation attendance (co-PARS) were assessed. Following an intention-to-treat approach, repeated-measures linear mixed models were used to explore intervention effects.

Results

Significant improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness (p=0.002) and vascular health (p=0.002) were found in co-PARS compared with usual care and no-treatment at 12 weeks. No significant changes in PA or well-being at 12 weeks or 6 months were noted. Intervention engagement was higher in co-PARS than usual care, though this was not statistically significant.

Conclusion

A coproduced PA behaviour change intervention led to promising improvements in cardiorespiratory and vascular health at 12 weeks, despite no effect for PA levels at 12 weeks or 6 months.

Trial registration number

Keywords: cardiovascular health, self-determination theory, exercise referral, behaviour change, translational research, vascular medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study advances the literature on exercise referral effectiveness by pragmatically evaluating a coproduced physical activity referral intervention, which was underpinned by multiple stakeholders and behaviour change theory.

The study documents the third phase of a novel and iterative approach which coproduced, piloted and then evaluated (this study) a physical activity referral intervention that was deemed feasible to implement in practice.

Objective and subjective measures provide insight into the potential effects for patient health.

It is not possible to directly attribute intervention effects to the phased coproduction approach, although supported by the Medical Research Council.

A larger sample size is needed to substantiate findings.

Introduction

Physical inactivity is the fourth-leading cause of death worldwide and costs the UK an estimated £7.4 billion annually, including £0.9 billion to the National Health Service (NHS) alone.1 Exercise referral schemes (ERSs) provide a promising framework to facilitate physical activity (PA) behaviour change in at-risk populations. Typically, UK ERSs consist of a referral from a healthcare professional to the 12–16 weeks tailored exercise programme provided by a qualified practitioner.

There is inconsistent evidence as to the effectiveness of ERSs on PA behaviour, mental well-being, quality of life and physical health outcomes.2–4 More recently, however, promising effects of ERSs have been demonstrated in Wales,5 Sweden6 and Spain7 and a systematic review identified promising effects of UK ERSs on self-reported PA and cardiovascular health markers.8 Prior et al9 demonstrated that for every 11 participants referred to a 24-week ERS, 1 participant went on to report achieving ≥90 min/week of PA at 12 months. For perspective, it is estimated that 67–167 patients (categorised as <10% cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk) need to receive statin treatment for 5 years to prevent one major vascular event.10 While we are not suggesting PA behaviour change is a comparable outcome to a serious clinical event, it is notable that replacing 30 min of television viewing time with PA across the UK population, could reduce premature mortality by 5%–15%, depending on activity intensity.11 The majority of studies evaluating ERSs, however, have drawn on self-reported PA data and future studies employing device-based measures are needed to substantiate these observations.

Despite recent promise for the effectiveness of ERSs,7–9 12 substantial heterogeneity exists in both design and delivery,13 14 reflecting varying assumptions on how best to promote health behaviour change.15 16 This limits potential scalability of ‘successful’ ERSs. Traditionally, ERSs have focused on short-term exercise prescription without appropriate evidence of effectiveness or underpinning of behaviour change theory.17 A recent attempt to integrate behaviour change theory into an ERS,18 however, showed no advantage over a standard ERS at 12 weeks or 6 months. The authors noted considerable implementation challenges when training staff, such as work-related demands that may have reduced the importance of the theory-based training. It is plausible that delivery staff asked to implement interventions designed by academics may lack ownership and feel less motivated/competent. One potential way to promote ownership and engagement might be to adopt a co-production approach, as a means of cocreating value across the public sector.19–21 Though not a panacea, the involvement of practitioners, managers and service-users in coproduction has potential to improve intervention relevance, fidelity and effectiveness.22

Previously, a theoretically grounded PA referral scheme (coproduced PA referral scheme, Co-PARS) was coproduced by academics, policy-makers, practitioners and service-users23 in Liverpool, UK, with a focus on supporting sustainable PA behaviour change. Liverpool is the third most deprived local authority in England and has the second highest proportion of Lower Super Output Areas in the most deprived 10% nationally.24 Interventional work with at-risk patients is therefore critical and is aligned with the concept of proportionate universalism.25 Underpinned by self-determination theory,24 the coproduced intervention differed from usual ERS care in its focus on PA behaviour change (rather than exercise prescription), and inclusion of frequent one-to-one consultations with exercise referral practitioners (compared with usual care which included formal contact at induction only). A pilot of co-PARS26 showed clinically meaningful improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) and PA, although as we did not include a usual care control, it was unknown whether these effects were due to the fact participants were taking part in an ERS or due to the unique elements of co-PARS. Furthermore, despite having very low CRF (<27.7 mL/kg/min)26 we found 64% of the baseline pilot sample were meeting the PA guidelines27 of at least 150 min moderate-intensity PA per week (measured objectively via accelerometry). This suggested CRF may be a more appropriate primary outcome measure than PA for this low-fit population (while changing PA behaviour was the focus of the intervention, a target health outcome of this behaviour change was improved CRF). The pilot also allowed the opportunity to investigate delivery processes, and we noted several areas that required refinement in preparation for a controlled trial. These refinements included, increasing the number of behaviour change consultations from four to five; enhanced focus on daily PA opportunities (rather than focussing on activities offered at the fitness centre); adapting staff timetables to promote consistency of care and to allow participant one-to-one consultations to take place in a private room; and reducing practitioner paperwork. Building on our previous pilot work, the aim of the current study was to investigate the effectiveness of co-PARS compared with a usual care ERS and a no-treatment control (NTC) on change in CRF at 12 weeks and PA and well-being at 6 months.

Methods

Study design

A three-arm quasi-experimental trial involving: (1) co-PARS (delivered at fitness centre A); (2) usual care ERS (delivered at fitness centre B) and (3) NTC. This paper reports trial outcomes (CRF, vascular health, PA, mental well-being) measured at baseline, 12 weeks and 6 months (PA and mental well-being only). Additional data were collected to investigate psychosocial processes of change, intervention fidelity and cost-effectiveness; due to space limitations they are not considered in the present manuscript, but findings can be obtained on request from p.m.watson@ljmu.ac.uk. Full written consent was obtained from participants.

Patient and public involvement

The intervention was previously coproduced, piloted and adapted with substantial service user input.23 26 In summary, this process involved several iterative development workshop with commissioners, managers, service providers, service users and researchers to develop a co-PARS framework. This coproduction process resulted in an intervention framework that was designed to be implemented within existing infrastructures. A subsequent pilot study explored the preliminary health impact and acceptability of co-PARS. Findings from this pilot phase informed adaptations to co-PARS that allowed for improved intervention feasibility, prior to conducting the present trial.

Participants and recruitment

Inclusion criteria were the same for all three conditions (co-PARS, usual care, no-treatment). Participants were eligible if aged ≥18 years with a health-related risk factor (eg, hypertension, hyperglycaemia, obesity) and/or health condition (eg, diabetes, CVD, depression) that may be alleviated by increasing PA levels. Participants with uncontrolled health conditions, severe psychological or neurological conditions were excluded. Participants for the co-PARS and usual care arms were recruited from fitness centre A (co-PARS) and fitness centre B (usual care), respectively (where they had been referred for exercise by a health professional). Reception staff at both centres provided study information and gained consent to pass participant details to the researcher. Participants for the NTC were recruited via posters, electronic invitations and email communications primarily at the university site. Participants were not eligible for the NTC if they were currently attending an ERS. Interested participants for all groups were sent an information sheet and baseline data collection was arranged.

Study arms

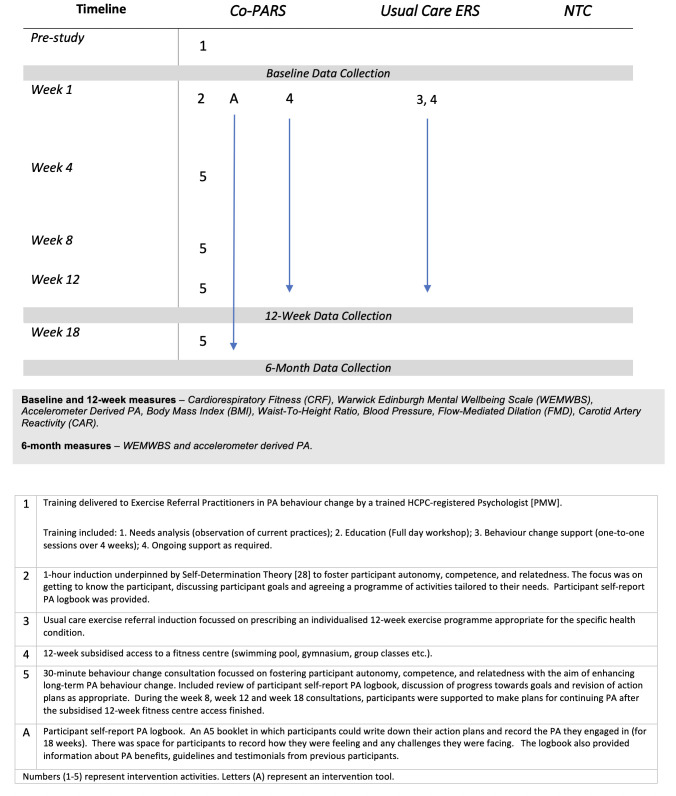

Intervention arm components are presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

‘PaT Plot’ describing intervention arm components.55 Co-PARS, coproduced PA referral scheme; ERS, exercise referral scheme; NTC, no-treatment control; PA, physical activity; HCPC, health & care professions council.

Usual care ERS: centre B

Usual care followed a standard ERS model of 12-week subsidised access to a fitness centre (swimming, gym, group classes). Participants met an exercise referral practitioner for an initial, 1-hour induction (week 1) during which a 12-week exercise programme was provided for the participant. Any further contact with a practitioner was informal and opportunistic. This system was already in place and was considered usual care for the local area. Centre B was chosen as a comparison centre due to its similarity in referral numbers and socioeconomic make-up of the local population to centre A (where co-PARS was being delivered). For example, based on areas within Liverpool ranked from 1 (most deprived) to 30 (least deprived), usual care ERS and co-PARS were ranked, respectively: 20th and 21st (income), 20th and 21st (employment), 22nd and 24th (Education) and 10th and 11th (living environment).

Co-PARS: centre A

Participants received the same 12-week subsidised access to a fitness centre as usual care plus a series of one-to-one behaviour change consultations (60 min induction, followed by 30 min consultations at weeks 4, 8, 12 and 18). A log book was provided for each participant to set action plans, log progress and facilitate consultation discussions. Consultations were delivered by exercise referral practitioners in an autonomy supportive counselling style, drawing on the principles of self-determination theory.28 This additional support aimed to encourage habitual opportunities to increase PA as well as activities available at the fitness centre. A full description of the theoretical underpinning and behaviour change intervention components is available elsewhere.23

Prior to the pilot of co-PARS26 practitioners received training in self-determination theory-based communication strategies led by a sport and exercise psychologist (last author (PMW)), involving a workshop, one-to-one sessions and follow-up group meetings. Following the pilot, a further series of group meetings involving exercise referral practitioners and the research team were held to develop aspects of delivery that required refinement (as outlined in the introduction). Full details of the training are available from p.m.watson@ljmu.ac.uk).

No-treatment control

Participants received a lifestyle advice booklet only (offered to all study arms at baseline data collection), based on national guidance for PA, nutrition, smoking cessation and alcohol consumption.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

CRF: Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max-2) was estimated via the submaximal Astrand-Rhyming cycle ergometer protocol.29 The protocol is a single-stage cycling test designed to elicit a steady-state heart rate over a period of ~6 min.

Accelerometer-derived PA

Tri-axial ActiGraph GT3x accelerometers (ActiGraph, Pensacola, Florida, USA) measured PA for 7 days, which have been validated in a comparable population.30 Raw triaxial acceleration values were converted into an omnidirectional measure of acceleration, referred to as Euclidian norm minus one.31 Minimum wear time was 10 hours per day and 3 days per week including 1 weekend day.32 The R package ‘GGIR’31 facilitated extraction of user-defined acceleration thresholds: 5.9–69.1 mg for light-intensity PA,33 69.1–258.7 mg as moderate and >258.7 mg as vigorous-intensity PA.34

Vascular health

Our previous work has demonstrated carotid artery reactivity (CAR) may be a promising outcome variable to assess in PA interventions for at-risk populations.35 Further, endothelial function may provide prognostic value beyond that of traditional risk factors36 with an increase of 1% in brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) associated with a 12%–15% lower risk of CV events.33 34 FMD and CAR were measured using ultrasound techniques.35 Both techniques measure vascular endothelial function and have independently predicted future risk of cardiovascular events in humans.36 37 Blood pressure was measured in the supine position using an automated blood pressure device (Omron Healthcare UK, Milton Keynes, UK).

Anthropometric measures

Since obesity is a critical risk factor for poor health and CVD, anthropometric variables were measured to investigate potential intervention effects on body mass. Waist-to-height ratio is a stronger predictor of early health risk than body mass index (BMI) alone,38 therefore, we collected both BMI (mass in kg/stature in m2) and waist-to-height ratio (waist circumference/stature).

Mental well-being

As PA is known to enhance mental well-being39 and clinical populations are more susceptible to mental ill health,40 it was important to identify whether co-PARS led to any changes in mental health (positive or negative). Mental well-being was measured using the 14-item Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS,41 which asks participants to rate their psychological well-being (eg, ‘I’ve been feeling cheerful’) over the previous 2 weeks (measured on a Likert scale of 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time)).

Fitness centre engagement (co-PARS and usual care only)

The number of occasions participants attended the fitness centre between baseline and 12 weeks (weekly attendance) and 12 weeks to 6 months (monthly attendance) was obtained from computerised attendance records. When measuring intervention engagement, it was deemed inappropriate to calculate the mean number of sessions per week, since this could exaggerate the engagement of individuals who attended with high frequency in the early weeks then dropped out (when compared with individuals who attended moderately but consistently for the full 12 weeks). Therefore, a formula was used to calculate a percentage for ‘12-week engagement’ (based on the recommended biweekly attendance):

n1 = number of weeks in which participant attends once only

n2 = number of weeks in which participant attends twice

n3 = number of weeks in which participant attends three or more times.

This formula took into account both frequency and consistency of attendance to yield a percentage score that ranged from 0% (no attendance) to 120% (attendance of three or more times per week for the whole 12 weeks).

Monthly attendance post-12 weeks was calculated as a mean attendance across months 4–6, therefore, did not take consistency of attendance into account.

Behaviour change consultation attendance (co-PARS only)

A number of consultations offered and attended were measured by exercise referral practitioners at induction, 4, 8, 12 and 18 weeks.

Sample size

Sample size was determined to detect a meaningful difference in CRF at 12 weeks based on our pilot results.26 To detect a difference of 2 mL/kg/min between co-PARS and usual care, 42 participants were required per arm (f=0.25, p=0.05, power=0.80). To detect a difference of 3.2 mL/kg/min between the intervention arms and the NTC, 17 participants were required for the NTC (f=0.5, p=0.05, power=0.80). Thus, a total sample of 101 participants were required.

Statistical analyses

An intention-to-treat approach was used assuming no change in non-respondents (last observation carried forward) to produce a conservative estimate of intervention effects. Delta changes (∆) from preintervention to postintervention were calculated for each group and entered as the dependent variable in repeated measures linear mixed model analyses. A random intercept model was used with fixed effects for study arm (co-PARS, usual care ERS, NTC) and time (baseline-to-week-12 change, week-12-to-6-month change and baseline-to-6-month change) and participants included as random effects. Least squared difference was used for post hoc testing. Testing for baseline differences to identify covariates was avoided, as this method has been demonstrated to inflate bias, instead preintervention was entered into the model as a covariate. Furthermore, all linear mixed model analyses were repeated with age and employment as covariates as a comparison to the results presented in this study (with baseline score as a covariate) due to their known prognostic value. Using age and employment as covariates resulted in no change in inferences presented in this study. One-way analysis of variances were used to compare baseline values between intervention arms. Fitness centre engagement was determined as described above. Behaviour change consultation attendance is presented descriptively. For non-normally distributed data, median and IQR is presented and within group median change was calculated via Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Results

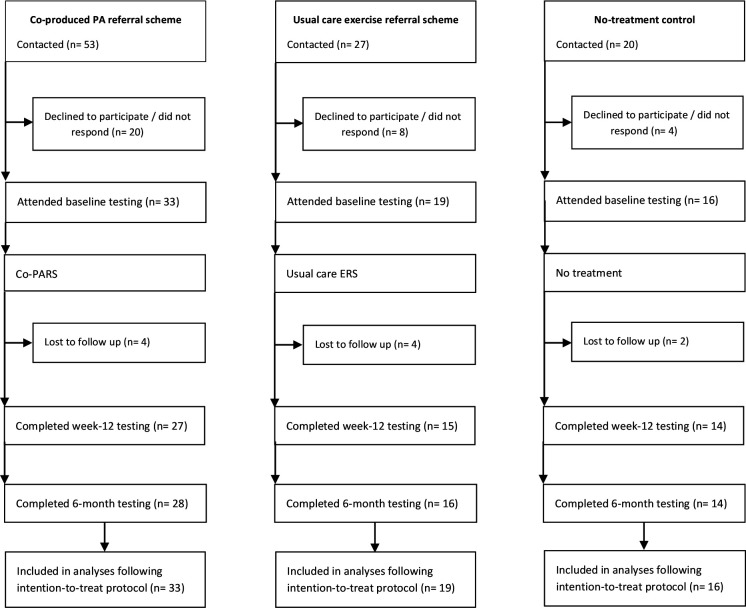

Participants: Sixty-eight participants provided baseline data, 56 of whom provided 12-week data and 58 of whom provided 6-month data (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Participant flow diagram within the three study arms (March 2018–January 2019). Co-PARS, coproduced PA referral scheme; ERS, exercise referral scheme; PA, physical activity.

Baseline characteristics

No significant differences were noted between arms for age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, referral reason or accelerometer-derived PA levels (p>0.05). Full-time employment status (p=0.001) and CRF (p=0.015) were significantly higher in the control compared with usual care and co-PARS. Smoking status was significantly higher in usual care compared with co-PARS and control (p=0.010). Mental well-being was significantly lower in co-PARS compared with control (p=0.023) (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics presented as mean±SD or % (N) of group

| Coproduced PA referral (n=33) |

Usual care ERS (n=19) |

No-treatment control (n=16) |

Between arm P value |

|

| Age (years) | 57±12 | 53±16 | 48±15 | p=0.319 |

| Female (% of sample) | 58 (19) | 47 (9) | 56 (9) | p=0.774 |

| White British (% of sample) | 82 (27) | 95 (18) | 75 (12) | p=0.132 |

| Full-time employment (% of sample) | 18 (6) | 26 (5) | 62 (10) | p=0.001 |

| Never smoked (% of sample) | 73 (24) | 37 (7) | 81 (13) | p=0.002 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31±7 | 33±6 | 29±6 | p=0.226 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 131±11 | 138±18 | 123±12 | p=0.010 |

| Primary referral reason/health concern (control) | p=0.132 | |||

| Cardiometabolic (% of sample) | 67 (22) | 43 (8) | 62 (10) | – |

| Cancer (% of sample) | 6 (2) | 5 (1) | 6 (1) | – |

| Mental health (% of sample) | 18 (6) | 26 (5) | 19 (3) | – |

| Musculoskeletal (% of sample) | 9 (3) | 26 (5) | 13 (2) | – |

| Comorbidity (% of sample) | 85 (28) | 100 (19) | 81 (13) | p=0.166 |

| Meeting the PA guidelines (% of sample)* | 73 (22) | 71 (10) | 93 (13) | p=0.223 |

P values represent between arm baseline effects. There was no between arm effect for referral reason, thus, no between arm p values are provided for referral reason subgroups.

*Chief Medical Officers’ 2019 PA guidelines: 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity per week.

ERS, exercise referral scheme; PA, physical activity.

Baseline-to-12-week effects

Raw outcome values are presented for baseline, week 12, and 6 months in table 2. There was a significant effect for study arm in baseline-to-12-week change in CRF (p=0.002). Post hoc testing revealed a significantly higher CRF change in Co-PARS (2.4) compared with the ERS (0.3; p=0.021) and control (−0.6; p=0.001), but no difference between the ERS and control (p=0.314). A significant effect for study arm was found in change in FMD% (p=0.002), with FMD% change significantly higher in Co-PARS (2.4) compared with control (−1.1; p=0.001) but not the ERS (0.8; p=0.099). The change in FMD% was not significantly different between the ERS and control (p=0.71). No statistically significant study arm effects were noted for changes in CAR%, blood pressure, resting heart rate, anthropometric measures, PA or WEMWBS at 12 weeks (p>0.05).

Table 2.

Cardiometabolic health outcomes and PA levels at baseline, 12 weeks, 6 months and between arm baseline to 12 weeks or 6 months effect

| Co-PARS | Usual care ERS | No-treatment control | ||||||||

| Baseline | Week 12 | 6 months | Baseline | Week 12 | 6 months | Baseline | Week 12 | 6 months | Between arm effect P value* | |

| Fitness (n=56) | ||||||||||

| CRFmL/kg/min | 22.2±7 | 24.6±7 | – | 23.3±6.6 | 23.6±7 | – | 29.6±9.2 | 28.9±8.7 | – | p=0.002 |

| Physical activity | ||||||||||

| GT3x (n=61) Mins.day | ||||||||||

| Light intensity | 90±52 | 98±64 | 107±75 | 98±36 | 93±31 | 158±145 | 90±37 | 101±33 | 86±40 | p=0.332 |

| Moderate intensity | 44±32 | 42±29 | 42±33 | 43±28 | 43±30 | 55±55 | 60±31 | 65±24 | 54±21 | p=0.260 |

| Vigorous intensity | 1±3 | 1±2 | 1±2 | 1±2 | 1±1 | 1±2 | 2±4 | 2±3 | 3±8 | p=0.108 |

| Vascular ultrasound (n=64) | ||||||||||

| CAR% | 1.7±2.7 | 2.8±2.2 | – | 2.7±1.8 | 3.9±2.8 | – | 2.5±2.7 | 1.7±2.7 | – | p=0.073 |

| CAR Baseline cm | 0.69±0.07 | 0.69±0.06 | – | 0.69±0.08 | 0.7±0.09 | – | 0.65±0.07 | 0.64±0.06 | – | p=0.130 |

| FMD% | 4.4±2.3 | 6.8±2.7 | – | 4.2±2 | 5±2.1 | – | 6.2±2.1 | 5.2±2.8 | – | p=0.002 |

| FMD Baseline cm | 0.39±0.07 | 0.38±0.06 | – | 0.39±0.09 | 0.41 0.08 | – | 0.38±0.08 | 0.37±0.06 | – | p=0.728 |

| Cardiometabolic (n=68) | ||||||||||

| BMI kg.m2 | 31±7 | 30±7 | – | 33±6 | 32±6 | – | 29±6 | 29±6 | – | p=0.323 |

| WHR | 62±9 | 61±10 | – | 64±8 | 63±8 | – | 56±9 | 56±9 | – | p=0.261 |

| SBP mm Hg | 131±11 | 127±12 | – | 138±18 | 132±15 | – | 123±12 | 118±13 | – | p=0.937 |

| DBP mm Hg | 73±7 | 71±8 | – | 73±9 | 71±11 | – | 72±11 | 68±10 | – | p=0.584 |

| RHR bpm | 70±10 | 65±10 | 70±12 | 68±11 | 66±12 | 63±9 | p=0.540 | |||

| Mental well-being (n=68) | ||||||||||

| WEMWBS | 46±9 | 51±10 | 48±10 | 49±10 | 52±11 | 50±13 | 53±9 | 56±9 | 53±10 | p=0.796 |

All variables are presented as mean±SD.

* F-statistic for between arm baseline-to-6-month change or baseline-to-week 12 change if variable not collected at 6 months.

BMI, body mass index; CAR, carotid artery reactivity; Co-PARS, co-produced PA referral scheme; CRF, cardiorespiratory Fitness; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ERS, exercise referral scheme; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; GT3x, Accelerometer; PA, physical activity; RHR, resting heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; WEMWBS, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale; WHR, waist-to-height ratio.

Baseline-to-6-month effects

No statistically significant study arm effects were noted for change in WEMWBS or PA at 6 months (p>0.05).

Fitness centre engagement (co-PARS and usual care ERS) and consultation attendance (co-PARS only)

Table 3 reports the participant fitness centre engagement data for the co-PARS and usual care ERS. Although not statistically significant, co-PARS engagement was 9% higher, participants attended the fitness centre on average three times more per month, and 23% more participants were attending the fitness centre beyond 6-month follow-up compared with usual care. Co-PARS behaviour change consultation attendance is reported in table 4.

Table 3.

Fitness centre engagement

| Co-PARS (n=33) |

Usual care (n=19) |

Between centre difference | |

| % engagement* (mean±SD) | 42±29 | 33±27 | p=0.267 |

| No of fitness centre visits (per person per month) week 12 to 6 months (Med, IQR) | 3 (0–14) | 0 (0–1) | p=0.072 |

| % of baseline sample who attended fitness centre at least once beyond 6 months (% of sample, n) | 39 (13) | 16 (3) | p=0.101 |

*Based on the formula (((n1*0.5)+(n2)+(n3*1.2))/12) * 100; n1=number of weeks in which participant attends once only; n2=number of weeks in which participant attends twice; n3=number of weeks in which participant attends three or more times. *Engagement;.based on a recommended attendance of twice weekly, a formula was used to calculate a percentage for ‘12-week engagement’, which took into account both frequency and consistency of attendance (see the Methods section).

Co-PARS, coproduced PA referral scheme.

Table 4.

Co-PARS behaviour change consultation attendance (based on baseline sample of 33 participants)

| Consultation | % Booked (n) | % Attended (n) |

| Induction | 91 (30) | 93 (28) |

| Week 4 | 82 (27) | 78 (21) |

| Week 8 | 67 (22) | 91 (20) |

| Week 12 | 64 (21) | 81 (17) |

| Week 18 | 55 (18) | 50 (9) |

Co-PARS, coproduced PA referral scheme.

Missing data were due to inability to complete the CRF test (n=12), inability to complete the vascular ultrasound protocols (n=4), and insufficient accelerometer wear time or non-return (n=7).

Discussion

This was the first study to investigate the effectiveness of a theoretically grounded, co-PARS compared with a usual care ERS and NTC. Despite challenges in recruitment that meant the study was statistically underpowered, the findings demonstrated significant and clinically meaningful improvements in CRF and vascular health in co-PARS compared with the usual care and no treatment. No statistically significant effects were noted for accelerometer-derived PA levels or mental well-being at 12 weeks or 6 months.

The effect of usual care ERSs compared with theoretically grounded interventions on CRF has not been previously explored. We observed a significant increase in CRF in co-PARS compared with usual care and NTC. According to values reported by Clausen et al42 both Co-PARS (22 mL/kg/min) and usual care (23 mL/kg/min) participants were below the lower limit of ‘healthy’ (27.7 mL/kg/min) for baseline CRF.43 As low CRF is associated with a substantially elevated risk of all-cause mortality,43 the magnitude of change demonstrated in Co-PARS (2.4 mL/kg/min) may be clinically meaningful. For example, in at-risk populations, relatively small magnitudes (≤1 mL/kg/min) have been shown to significantly reduce clustered cardiometabolic risk.44 Thus, co-PARS was effective at improving CRF in individuals with low CRF by a clinically meaningful amount.

Promising improvements in vascular health were also noted in the co-PARS group, with brachial artery FMD significantly improved compared with usual care and NTC arms. Although CAR was not statistically different between arms, both co-PARS and usual care demonstrated a potentially meaningful within-arm improvement compared with NTC, which exhibited a deterioration in vascular health. Such improvements in vascular measures may have prognostic implications. For example, a 1% increase in FMD has been suggested to reduce the future risk of CVD events by 13%.36

Despite low baseline CRF, a substantial percentage of co-PARS (73%) and usual care (71%) participants were meeting the Department of Health45 guidelines of 150 min of moderate-intensity PA per week. We observed a similar finding in our pilot26 and subsequently raised the question as to the use of PA guidelines to assess eligibility for ERSs (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014), as it appears from our data that individuals classified as ‘PA’ can still be very unfit, and therefore, can benefit from ERSs in terms of improved fitness and cardiometabolic health. A further discrepancy was noted in the lack of change in PA levels in co-PARS, despite improved CRF. It is possible measurement issues contributed to this discrepancy. Accelerometers can measure certain types of PA such as walking, running and stair climbing.46 They may not, however, sufficiently identify activities typical of an ERS delivered within a fitness centre environment (eg, cycling, resistance training, circuits, swimming). Given co-PARS had higher (although non-significant) fitness centre engagement compared with usual care, it is possible PA changes occurred that were not detected by the accelerometry data. Consideration, therefore, needs to be given to the appropriateness of accelerometers to measure PA in ERSs. Alternative methods such as heart rate monitors combined with self-report data may be worthy of consideration, although further work would be required to develop standardised data collection and analysis protocols (taking into account the limitations of each of these methods if used in isolation47). Researchers are therefore, urged to consider CRF as a primary outcome in ERSs until appropriate alternative methods of measuring PA behaviour are developed. Ultimately, it is not clear why the increase in fitness occurred without a corresponding change in PA and further research is required to elucidate the relationship between PA and fitness in this population.

In addition to physiological health outcomes, we found baseline mental well-being to be below the national average (score of 50) in both co-PARS (46) and usual care (49), but not the NTC (53).48 Despite no significant between-group effect for mental well-being, within-group changes at 12 weeks were deemed clinically meaningful for co-PARS (5) and usual care (3) but not in the NTC. It is notable that the post-intervention magnitude of change observed in mental well-being for Co-PARS (5) was larger than that observed in a meta-analysis encompassing >23 000 participants across 13 different ERSs (3), which were comparable in nature to the usual care ERS in this study.49

From the 6-month data, it appeared the scheme was not effective at promoting sustained PA behaviour change or mental well-being improvements. It must be noted, however, that the well-being levels were still higher than baseline and even small magnitudes of change (1–3) may be meaningful in clinical populations.50 As discussed earlier, it may be that measuring PA using the methods described in this study prevented the identification of activities typical of a fitness centre environment. This notion is supported by the post-week-12 attendance data, which highlighted co-PARS participants were regularly attending the fitness centre whereas the usual care participants were not. Challenges of maintaining sustained health outcomes post-ERSs have been highlighted elsewhere.3 And while a recent systematic review reported longer length schemes (>20 weeks) may be more effective than shorter schemes,8 the four long ERSs (20–26 weeks) collected pre–post data only. Thus, we do not know if longer length ERSs result in enhanced health outcomes post-intervention compared with shorter schemes. To determine if longer length schemes are indeed more effective, longer-term follow-up data collection is required, ideally at 6 and 12 months post-intervention.51

Through a phased approach we have assessed the effectiveness of co-PARS resulting from several years of coproduction. While the effects of coproduction are difficult to isolate, a comparison of results at different stages of intervention refinement suggests the phased development approach had some positive effects. Unpublished engagement data from centre A in 2014–2015 (when the centre was running a usual care ERS) shows that engagement improved after the introduction of co-PARS (42% vs 28% in 2014–2015), whereas engagement reduced in the usual care centre over the same period (32% vs 37% in 2014–2015). Furthermore, consultation attendance for Co-PARS in the current study was substantially higher than in our previous pilot (54% attended induction plus ≥3 behaviour change consultations, vs 9% in the pilot26), which may have been a reflection of refinements made to the intervention after the pilot (eg, improved focus on holistic PA, improved monitoring procedures, improved continuity of instructors). These improvements in engagement highlight the importance of allowing time for complex interventions to develop,52 and are particularly promising given the effectiveness of ERSs are highly dependent on participant adherence.5 21 Furthermore, this study has demonstrated how investing in the ‘bottom-up’ development of an intervention can lead to an effective and sustainable model. We, therefore, support the arguments of Rutter et al 53 in that a shift in thinking is needed, instead of asking whether an intervention works to fix a problem, researchers should aim to identify if and how it contributes to reshaping a system in a favourable way. As such, we propose the coproduction and implementation process may be as important as the scheme content itself.

Methodological considerations

This is the first known study to investigate the effectiveness of a co-PARS in comparison to usual care and an NTC. Our novel approach addresses an important gap in the sport and exercise medicine literature,54 in that we employed rigorous laboratory-based instruments to measure health outcomes that can be achieved through an ecologically valid, ‘real-world’ intervention. We observed a very high retention at 6-month follow-up, which may be due in part to the fact many of the participants were retired (and therefore may have more available time). It is possible also that the high retention was facilitated by the coproduction process, which involved ongoing relationships between the research and delivery teams (and therefore helped with the logistics of returning accelerometers for the co-PARS and usual care groups). While this paper highlights many strengths of coproduction, we do not wish to present coproduction as a panacea19 and it is important potential challenges and costs are considered prior to undertaking such an approach.21 22

We must acknowledge some limitations of the study. While there is a need for high-quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of theoretically informed approaches to PA behaviour change,3 several pragmatic reasons meant an RCT approach was not appropriate for the present study. First, it was important participants could choose the most convenient fitness centre. Second, it was important we continued work with the same fitness centre and staff (following coproduction23 and pilot26 phases) in order to develop the intervention to the point where it was deemed to have a worthwhile effect.52 A pragmatic research approach was, therefore, deemed most appropriate to evaluate co-PARS with high ecological validity. Pragmatic constraints (eg, fitness centre refurbishments, staff illness) did, however, mean the required sample size was not achieved, thus inferences of effectiveness need to be taken with caution. This is particularly true for the PA data, where the relatively high variability (compared with CRF) may have contributed to the lack of change observed in PA in this study. It is recommended future work considers pragmatic risks and contingencies when planning recruitment and plans sufficient time to cope with recruitment delays. For pragmatic reasons, not all outcomes were collected at 6 months follow-up and further research is needed to collect long-term, objective health data following PA referral schemes. Finally, it must be noted that while the trial registration appears to be retrospective (6 April 2018), the initial submission was several months prior to this (11 January 2018). Final sign-off was delayed due to capacity issues within the research team.

Conclusion

A coproduced, theoretically grounded PA referral scheme (co-PARS) led to improved CRF and vascular health in at-risk individuals when compared with usual care and NTC. In addition, clinically meaningful improvements in vascular health and mental well-being were observed at 12 weeks in both co-PARS and usual care, but not the NTC group. Of note, PA remained unchanged at 12-weeks and 6-months follow-up. Adopting a phased approach has enabled multistakeholder input and ongoing intervention refinement, resulting in an intervention that showed promising effects on engagement and clinically meaningful improvements to participant health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants in this study for their time, the delivery staff and centre managers for their ongoing support, and the initial development group involved in the co-production process.

Footnotes

Twitter: @BuckleyBenjamin

Contributors: BB contributed to the study design, data collection, data analysis and preparation of the final document. PMW, DT and RM contributed to the study design, data analysis and preparation of the final document. MC contributed to the data collection and approved the final version. LG, FG, DC, PW and GW intellectually contributed to this paper and approved the final version.

Funding: This project was supported by a PhD studentship for Benjamin Buckley from Liverpool John Moores University. The 6-month data collection and analysis was supported by a financial grant from NHS Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group (LCCG) RCF Award 2018/2019.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC: 18/NW/0039 - Project: 238547).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Additional data were collected to investigate psychosocial processes of change, intervention fidelity and cost-effectiveness; due to space limitations they are not considered in the present manuscript, but findings can be obtained on request from p.m.watson@ljmu.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Public Health England Physical activity: applying all our health, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dugdill L, Graham RC, McNair F. Exercise referral: the public health panacea for physical activity promotion? A critical perspective of exercise referral schemes; their development and evaluation. Ergonomics 2005;48:1390–410. 10.1080/00140130500101544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavey TG, Taylor AH, Fox KR, et al. . Effect of exercise referral schemes in primary care on physical activity and improving health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011;343:d6462. 10.1136/bmj.d6462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavey TG, Anokye N, Taylor AH, et al. . The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of exercise referral schemes: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:1–254. 10.3310/hta15440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy SM, Edwards RT, Williams N, et al. . An evaluation of the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the National exercise referral scheme in Wales, UK: a randomised controlled trial of a public health policy initiative. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:745–53. 10.1136/jech-2011-200689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onerup A, Arvidsson D, Blomqvist Åse, et al. . Physical activity on prescription in accordance with the Swedish model increases physical activity: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:bjsports-2018-099598 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martín-Borràs C, Giné-Garriga M, Puig-Ribera A, et al. . A new model of exercise referral scheme in primary care: is the effect on adherence to physical activity sustainable in the long term? A 15-month randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018;8:e017211. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowley N, Mann S, Steele J, et al. . The effects of exercise referral schemes in the United Kingdom in those with cardiovascular, mental health, and musculoskeletal disorders: a preliminary systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018;18:949. 10.1186/s12889-018-5868-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prior F, Coffey M, Robins A, et al. . Long-Term health outcomes associated with an exercise referral scheme: an observational longitudinal follow-up study. J Phys Act Health 2019;16:288–93. 10.1123/jpah.2018-0442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo A, et al. . Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2013:CD004816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wijndaele K, Sharp SJ, Wareham NJ, et al. . Mortality risk reductions from substituting screen time by discretionary activities. Med Sci Sport Exer 2017;49:1111–9. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craike M, Wiesner G, Enticott J, et al. . Equity of a government subsidised exercise referral scheme: a population study. Soc Sci Med 2018;216:20–5. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig A, Dinan S, Smith A, et al. . Exercise referral systems: a national quality assurance framework. Department of health: London, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavey T, Taylor A, Hillsdon M, et al. . Levels and predictors of exercise referral scheme uptake and adherence: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:737–44. 10.1136/jech-2011-200354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Littlecott HJ, Moore GF, Moore L, et al. . Psychosocial mediators of change in physical activity in the Welsh national exercise referral scheme: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:1–11. 10.1186/s12966-014-0109-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson CL, Oliver EJ, Dodd-Reynolds CJ, et al. . How do participant experiences and characteristics influence engagement in exercise referral? A qualitative longitudinal study of a scheme in Northumberland, UK. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024370. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sowden SL, Raine R. Running along parallel lines: how political reality impedes the evaluation of public health interventions. A case study of exercise referral schemes in England. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:835–41. 10.1136/jech.2007.069781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duda JL, Williams GC, Ntoumanis N, et al. . Effects of a standard provision versus an autonomy supportive exercise referral programme on physical activity, quality of life and well-being indicators: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:10. 10.1186/1479-5868-11-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostrom E. Crossing the great divide: coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev 1996;24:1073–87. 10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke D, Jones F, Harris R, et al. . What outcomes are associated with developing and implementing co-produced interventions in acute healthcare settings? a rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014650. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrance C, Tsofliou F, Clark C. Adherence to community based group exercise interventions for older people: a mixed-methods systematic review. Prev Med 2016;87:155–66. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rycroft-Malone J, Burton CR, Bucknall T, et al. . Collaboration and Co-Production of knowledge in healthcare: opportunities and challenges. Int J Health Policy Manag 2016;5:221–3. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buckley BJR, Thijssen DHJ, Murphy RC, et al. . Making a move in exercise referral: co-development of a physical activity referral scheme. J Public Health 2018;40:e586–93. 10.1093/pubmed/fdy072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.GOV.UK The English indices of deprivation 2019; 2019.

- 25.Carey G, Crammond B, De Leeuw E. Towards health equity: a framework for the application of proportionate universalism. Int J Equity Health 2015;14:81. 10.1186/s12939-015-0207-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buckley BJ, Thijssen DH, Murphy RC, et al. . Preliminary effects and acceptability of a co-produced physical activity referral intervention. Health Educ J 2019;001789691985332. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health & Social Care UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000;55:68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astrand I. Aerobic work capacity in men and women with special reference to age. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 1960;49:1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly LA, McMillan DGE, Anderson A, et al. . Validity of actigraphs uniaxial and triaxial accelerometers for assessment of physical activity in adults in laboratory conditions. BMC Med Phys 2013;13:1–7. 10.1186/1756-6649-13-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Hees VT, Gorzelniak L, Dean León EC, et al. . Separating movement and gravity components in an acceleration signal and implications for the assessment of human daily physical activity. PLoS One 2013;8:e61691. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews CE, Hagströmer M, Pober DM, et al. . Best practices for using physical activity monitors in population-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:S68–76. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182399e5b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakrania K, Yates T, Rowlands AV, et al. . Intensity thresholds on RAW acceleration data: Euclidean norm minus one (ENMO) and mean amplitude deviation (Mad) approaches. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164045. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hildebrand M, VAN Hees VT, Hansen BH, Hilded M, Vt H, et al. . Age group comparability of raw accelerometer output from wrist- and hip-worn monitors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:46. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buckley BJR, Watson PM, Murphy RC, et al. . Carotid artery function is restored in subjects with elevated cardiovascular disease risk after a 12-week physical activity intervention. Can J Cardiol 2019;35:23-26:23–6. 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inaba Y, Chen JA, Bergmann SR. Prediction of future cardiovascular outcomes by flow-mediated vasodilatation of brachial artery: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;26:631–40. 10.1007/s10554-010-9616-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Mil ACCM, Pouwels S, Wilbrink J, et al. . Carotid artery reactivity predicts events in peripheral arterial disease patients. Ann Surg 2019;269:767–73. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2012;13:275–86. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paluska SA, Schwenk TL. Physical activity and mental health. Sports Medicine 2000;29:167–80. 10.2165/00007256-200029030-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. . Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, et al. . The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:63–13. 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clausen JSR, Marott JL, Holtermann A, et al. . Midlife cardiorespiratory fitness and the long-term risk of mortality: 46 years of follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:987–95. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. . Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;301:2024–35. 10.1001/jama.2009.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simmons RK, Griffin SJ, Steele R, et al. . Increasing overall physical activity and aerobic fitness is associated with improvements in metabolic risk: cohort analysis of the proactive trial. Diabetologia 2008;51:787–94. 10.1007/s00125-008-0949-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Department of Health Start Active, Stay Active – A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Oficers. London: Departmet of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berlin JE, Storti KL, Brach JS. Using activity monitors to measure physical activity in free-living conditions. Phys Ther 2006;86:1137–45. 10.1093/ptj/86.8.1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strath SJ, Kaminsky LA, Ainsworth BE, et al. . Guide to the assessment of physical activity: clinical and research applications: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2013;128:2259–79. 10.1161/01.cir.0000435708.67487.da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris S, Earl K. Health survey for England 2016 well-being and mental health. Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wade M, Mann S, Copeland RJ, et al. . Effect of exercise referral schemes upon health and well-being: initial observational insights using individual patient data meta-analysis from the National referral database. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020;74:32-41. 10.1136/jech-2019-212674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shah N, Cader M, Andrews WP, et al. . Responsiveness of the short Warwick Edinburgh mental well-being scale (SWEMWBS): evaluation a clinical sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16:239. 10.1186/s12955-018-1060-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cavill N, Roberts K, Rutter H. Standard evaluation framework for physical activity interventions. National Obesity Observatory: Oxford, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, et al. . The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 2017;390:2602–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31267-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beedie C, Mann S, Jimenez A, et al. . Death by effectiveness: exercise as medicine caught in the efficacy trap! Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1–2. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perera R, Heneghan C, Yudkin P. Graphical method for depicting randomised trials of complex interventions. BMJ 2007;334:127–9. 10.1136/bmj.39045.396817.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.