Abstract

Background

Management of patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) requires subspecialized, comprehensive, multidisciplinary care. The Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation established the Care Center Network (CCN) in 2013 with identified criteria to become a designated CCN site. Despite these criteria, the essential components of an ILD clinic remain unknown.

Research Questions

How are ILD clinics within the CCN structured? What are the essential components of an ILD clinic according to ILD physician experts, patients, and caregivers?

Study Design and Methods

This study had three components. First, all 68 CCN sites were surveyed to determine the characteristics of their current ILD clinics. Second, an online, three-round modified Delphi survey was conducted between October and December 2019 with 48 ILD experts participating in total. Items for round 1 were generated using expert interviews. During rounds 1 and 2, experts rated the importance of each item on a 5-point Likert scale. The a priori threshold for consensus was more than 75% of experts rating an item as important or very important. In round 3, experts graded items that met consensus and ranked items deemed essential for an ILD clinic. Third, ILD patient and caregiver focus groups were conducted and analyzed for content to determine their perspectives of an ideal ILD clinic.

Results

Forty items across four categories (members, infrastructure, resources, and multidisciplinary conference) achieved consensus as essential to an ILD clinic. Patient and caregiver focus groups identified three major themes: comprehensive, patient-centered medical care; expanded access to care; and comprehensive support for living and coping with ILD.

Interpretation

The essential components of an ILD clinic are well-aligned between physician experts and patients. Future research can use these findings to evaluate the impact of these components on patient outcomes and to inform best practices for ILD clinics throughout the world.

Key Words: clinic structure, Delphi survey, focus groups, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis

Abbreviations: CCN, Care Center Network; ILD, interstitial lung disease; PFF, Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation

Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) represent a rare and heterogeneous group of more than 100 diseases. Among them, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is the most common and carries significant morbidity and mortality, with a median survival of 41 months.1 The scope of care for patients with ILD can be challenging and complex, ranging from obtaining accurate diagnoses, initiating disease-modifying treatments, providing supportive care, including oxygen therapy, and managing comorbidities to discussing lung transplantation and providing palliative and end-of-life care.

The multidimensional, complex, and longitudinal needs of this patient population has led to the emergence of specialized, comprehensive ILD clinics in the last two decades. The Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (PFF) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing support to those living with pulmonary fibrosis. In 2013, the PFF started the Care Center Network (CCN), which now consists of 68 designated medical centers across the United States recognized for having expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of ILD through multidisciplinary care and patient engagement in education, support, and research.

Although the PFF CCN delineates the criterion to qualify and maintain designated site status,2 little is known about the composition, structure, and function of an ideal ILD clinic. Because of a lack of clinical practice guidelines to inform the structure of an ILD clinic, we identified three objectives for this study: first, to assess the current structure of ILD clinics within the PFF CCN; second, to determine the essential components of an ILD clinic using a three-round modified Delphi survey administered to a group of ILD experts, all of whom are directors of PFF CCNs; and third, to identify the essential components of an ILD clinic from the perspectives of ILD patients and caregivers using a series of focus groups.

Methods

The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved the study (Identifier: COMIRB 19-0841, 19-1583).

Modified Delphi Survey Process

Survey

A 60-item, web-based survey using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) was sent to all 68 PFF CCN directors via e-mail to determine baseline characteristics and composition of their ILD clinics.

Identification of Modified Delphi Survey Items

Items included in the first round of the modified Delphi survey were compiled based on content analysis of transcripts from individual, semistructured telephone interviews with PFF CCN directors (e-Appendix 1). Nine directors were selected based on their clinical expertise and background to ensure representation with respect to sex, geography, and size of ILD clinic. All interviews were conducted by C. H., digitally recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

Selection of Expert Panel

All PFF CCN directors, including those who had participated in the telephone interviews, were invited via e-mail to participate in the modified Delphi survey.

Modified Delphi Survey Execution

We conducted a three-round Delphi survey using a secure, online REDCap database between October and December 2019. In rounds 1 and 2, the Delphi collaborators ranked items by degree of importance on a five-point Likert scale (very important, important, less important, not important, and not sure). In the third round, participants were instructed to rank items on a five-point Likert scale based on if items were thought to be essential to an ILD clinic (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, and not sure).

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed anonymously and reported according to the defined methodologic criteria for Delphi studies.3 The a priori threshold for an item to be considered important to an ILD clinic in Delphi rounds 1 and 2 was defined as more than 75% consensus among experts rating an item as “very important” or “important,” and the a priori threshold for an item to be considered not important to an ILD clinic was defined as more than 75% consensus among experts rating an item as “not important” or “less important.” The same thresholds were used for the third Delphi round, but in relationship to level of agreement with an item being “essential” for an ILD clinic.

Focus Groups

Study Design

We conducted focus groups with patients with ILD and self-identified caregivers. We chose a qualitative study design using content analysis as our methodologic framework to gain a comprehensive understanding of the experiences, wants, and needs of patients and caregivers seeking medical care at ILD clinics.

Participants and Recruitment

Eligible participants had to reside currently in the United States. Participants were not excluded if they were not currently or had not previously received care at a PFF CCN site. Participants were recruited at the PFF 2019 Summit at an informational table and through a recruitment flyer distributed electronically to the PF Warrior community e-mail distribution list. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of the focus group. Participants were not compensated for their time.

Data Collection

Real-time focus groups were conducted using a secure, web-based meeting interface and facilitated by authors (B. A. G., C. H., and M. M.) from November 2019 through January 2020. The focus groups followed a semistructured, open-ended approach to elicit participants’ opinions and experiences of ILD clinics (e-Appendix 2). All focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three focus groups initially were planned, but new themes emerged from the second and third groups. Therefore, two additional focus groups were conducted, after which thematic saturation was achieved based on debriefing after group meetings and note comparison by the moderator (B. A. G.) and comoderators (C. H. or M. M.). This number of groups is consistent with existing literature examining the relationship between number of focus groups conducted and thematic saturation.4,5

Analysis

Transcripts were entered into Atlas.ti version 8.0 software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH) and analyzed for content using a general inductive approach. Analysis was completed by organizing the data through open coding and repeated comparisons to identify key themes. The primary coders (B. A. G. and M. M.) met regularly to discuss coded data, to reconcile differences, and to achieve consensus. Both coders double-coded all focus groups. Coded data were analyzed within and across groups to identify the emergent themes.

Results

Modified Delphi Survey

Components of Current ILD Clinics within the PFF CCN

A total of 36 of 68 (53%) PFF CCN directors completed the survey (Table 1 and e-Table 1). The median number of new patient visits per year was 250 (interquartile range, 150-383), and the median number of total patient visits per year was 1000 (interquartile range, 500-1500). Sixty-seven percent of clinics were staffed with two to five physicians. Nearly all clinics (92%) had nursing support, with 56% of sites having dedicated ILD nurses. Available ancillary support staff varied across clinics. Every clinic participated in research and clinical trials. All clinics, except for one, held a multidisciplinary conference and conferences at least once per month.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of ILD Clinics in the PFF CCN

| Item | Result |

|---|---|

| Members | ... |

| No. of ILD-focused pulmonologists working in the ILD clinic | ... |

| 1 | 2 (6) |

| 2-5 | 24 (67) |

| > 5 | 10 (27) |

| Nursing support for the ILD clinic | 33 (92) |

| Nurses who are dedicated solely to ILD clinic (in the clinics with nurses) | 18 (56) |

| Advanced practice providers working in the ILD clinic | 18 (50) |

| Infrastructure | ... |

| New patient visits per y | 250 (150-383) |

| Total patient visits per y | 1000 (500-1,500) |

| No. of half days of ILD clinic per wk | 7 (4-8) |

| Average wait time from referral to clinic visit | ... |

| 1 wk-1 mo | 15 (42) |

| 1-3 mo | 16 (44) |

| 3-12 mo | 4 (11) |

| Unknown | 1 (3) |

| Most patients traveling > 60 min to get to clinic | 19 (53) |

| Use of telemedicine | 3 (8) |

| Resources | ... |

| Access to social worker | 11 (31) |

| Access to respiratory therapists | 24 (67) |

| Access to a palliative care program | 33 (92) |

| Access to a dedicated ILD palliative care program | 3 (8) |

| Access to a local pulmonary rehabilitation program | 36 (100) |

| Access to a local support group | 36 (100) |

| Participate in clinical trialsa | 35 (100) |

| Participate in patient registries | 32 (89) |

| Participate in biobanking of specimens | 31 (86) |

| Multidisciplinary conference | ... |

| Participation in a multidisciplinary conference | 35 (97) |

| Frequency of multidisciplinary conference | ... |

| > Once/wk | 1 (3) |

| Once/wk | 17 (49) |

| Once/2 wks | 9 (26) |

| Once/mo | 8 (23) |

Data are presented as No. (%) or median (interquartile range). CCN = Care Center Network; ILD = interstitial lung disease; PFF = Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation.

Only 35 respondents answered this question.

Expert Interview

Eight of the 9 identified PFF CCN directors participated in the telephone interviews. Eighty-seven total items were generated for inclusion in the first round of the modified Delphi survey. Items were divided into four categories: members of an ILD team, infrastructure for an ILD clinic, resources for an ILD clinic, and multidisciplinary conference.

Modified Delphi Survey

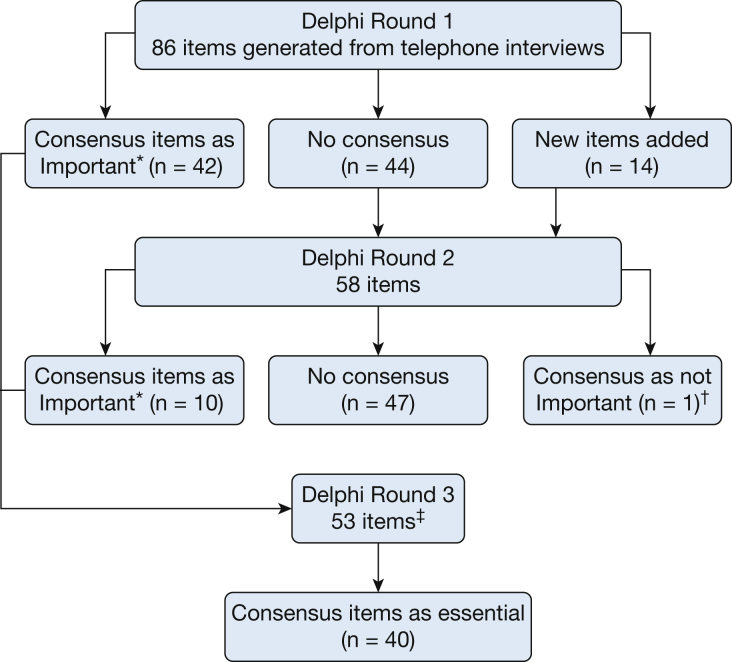

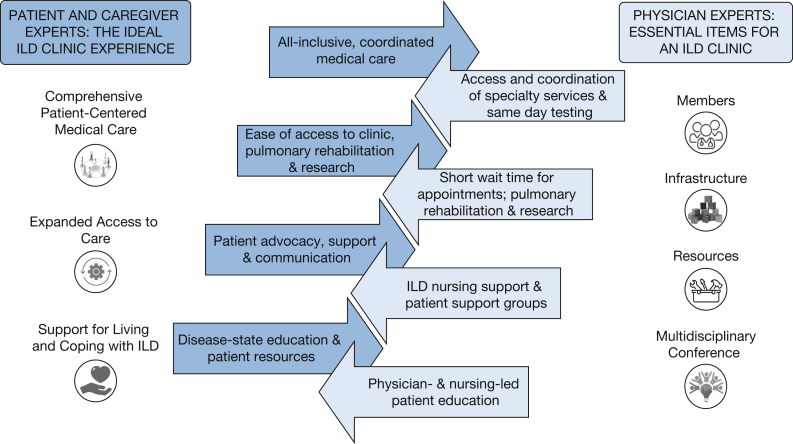

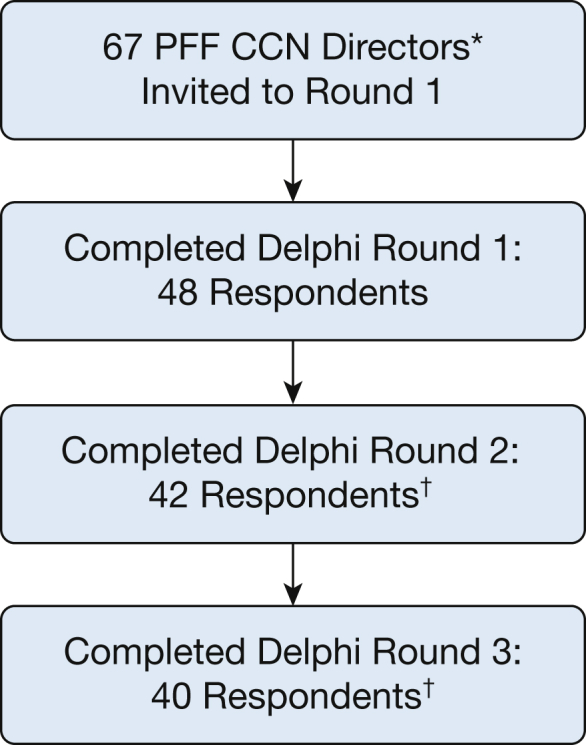

Of the 67 PFF CCN directors invited to participate (J. S. L., as PFF CCN Director at the University of Colorado, was not invited to participate), the response rate for the three rounds of modified Delphi was 48 (72%) for the first round, 42 (63%) for the second round, and 40 (60%) for the third round (Fig 1). The number of items in each round is summarized in Figure 2, and detailed results of all three rounds can be found in the online Supplemental Materials (e-Tables 2-4). At completion of the third round, 40 unique items achieved consensus as essential for an ILD clinic (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing of participation in each round of the modified Delphi survey by Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Care Center Network Directors. CCN = Care Center Network; ILD = interstitial lung disease; PFF = Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation. ∗Director from our institution excluded. †Directors invited to participant in subsequent rounds only if they completed the prior survey.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram showing items through each round of the modified Delphi process. The Delphi collaborators were asked to rank items in degree of importance for interstitial lung disease (ILD) clinics on a five-point Likert scale during each of the three rounds. During round 1, participants were given the opportunity to add any additional items they found important for an ILD clinic that were not included already in the first-round items. In the second round, the amended list of items (including the items generated in round 1) and results of the first round that did not achieve consensus were presented. Participants were asked to rate this amended list on the same five-point Likert scale. In the final round, participants ranked consensus items on a five-point Likert scale on whether these items were not only important, but also essential, for an ILD clinic. ∗Threshold of importance: 75% of respondents selected “very important” or “important.” †Item: If advanced practice providers are present in ILD clinic, their role mainly should be diagnosis of new ILD patients. ‡One item duplicated–total of 52 unique items in round 3.

Table 2.

Items That Achieved Consensus in the Modified Delphi Survey as Essential or Important for an ILD Clinic

| Items That Are Essential to Have for an ILD Clinic | Items That Are Important to Have for an ILD Clinic |

|---|---|

| Members of the ILD team | |

| Physicians | |

| Having expertise in ILD (a certain number of years working in ILD patient care) | |

| Having at least 2 or more pulmonologists working the ILD clinic | |

| Nurses | Dedicated ILD nurse |

| If a clinic has advanced practice providers | |

| Close supervision by physicians | |

| Their role should be mainly longitudinal care of ILD patients | |

| Research coordinators | Clinic coordinators |

| Fellows and trainees | |

| Infrastructure of ILD clinics | |

| General | |

| ILD clinic sees a minimum number of patients per year | |

| ILD clinic sees a minimum of 100 unique patients/ya | |

| Minimum number of clinics per week | |

| Ease of access to clinic | |

| Triaging and rerouting referrals to ILD clinics from general pulmonary clinics | |

| Triaging of ILD patients before new patient visit to avoid multiple visits (prescheduling tests before the visit, obtaining prior records and imaging, and so forth) | |

| The maximum time from referral to new appointment is less than 2 mo for a standard new patient visitb | Maximum time from referral to new appointment is less than 7-10 d for an urgent patient visit |

| Patient management strategies | |

| Providing a mix of primary management, collaborative/shared care, and consultative management | Providing primary management of ILD care |

| Exposure history | |

| Obtain a structured occupational and environmental exposure history for all new ILD patients | |

| Resources for ILD clinics | |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | |

| A pulmonary rehabilitation facility in close proximity (within a 30-60-min drive from the center) to the ILD clinica | |

| Ancillary services within the same institution | |

| General rheumatology | Access to rheumatologists with expertise in ILD |

| Thoracic radiology | Access to sleep clinic |

| Pulmonary pathologya | |

| Thoracic surgeon | |

| Pulmonary hypertensiona | |

| Cardiology | |

| Palliative care | |

| Experience in treating patients with advanced lung diseases | |

| Availability in outpatient, inpatient, and hospice care | |

| Pulmonary function testing | |

| Same-day appointments as the ILD clinic visit | |

| Radiology | |

| Dedicated ILD HRCT protocol | |

| HRCT available same day or next day of clinic visita | |

| Research | |

| Participation in research | |

| Participation in clinical trials | |

| Participation in patient registriesa | |

| Patient education | |

| Patient education is delivered by physiciansa | |

| Patient education is delivered by nurses | |

| ILD clinic participates in local patient support groups | |

| Multidisciplinary conference | |

| Having a multidisciplinary conference | Frequency is at least once/2 wks |

| Staff (routinely participates in ILD conference) | |

| Pulmonologists | Trainees |

| Radiologists | |

| Pathologists | |

| Discussing the following types of patients at multidisciplinary conference | |

| Complex cases with diagnostic or therapeutic dilemmas | |

| Patients who already have undergone surgical lung biopsy | |

| Patients in whom a surgical lung biopsy is being considered |

ILD = interstitial lung disease.

If threshold for agreement were increased to > 80%, these items would have been considered important, but not essential, for an ILD clinic.

Maximum time to new patient visit < 1 mo or < 3 mo for a standard new patient visit were important, but not essential.

In the third round, if we changed the threshold for essential to 70%, this would have added six items to the list of essential items for an ILD clinic, including inclusion of more specific personnel (clinic and research coordinators, access to rheumatologists with expertise in ILD) and a minimum frequency of multidisciplinary conference (e-Table 4). In contrast, if the threshold were more stringent, only allowing for those with more than 80% agreement, seven items would be excluded from the essential list, including a minimum number of unique patients seen yearly, specific ancillary services at the same institution, and proximity of a pulmonary rehabilitation center (Table 2).

Focus Groups

A total of 21 individuals participated: 16 patients and five family caregivers. We conducted five focus groups with a range of three to seven participants per group. Among the patient participants, 69% were men and 31% were women. Among the caregiver participants, 20% were men and 80% were women. Additional demographics were not obtained to maintain participant confidentiality; some participants provided details of their diagnoses voluntarily. We identified three major themes from the focus groups that encompass patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives of an ideal ILD clinic: comprehensive patient-centered medical care, expanded access to care, and support for living and coping with ILD. See Table 3 for the three major themes, with subthemes and representative quotations.

Table 3.

Major Themes and Subthemes With Representative Quotations From the Patient and Caregiver Focus Groups

| Theme | Subthemes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive, Patient-Centered Medical Care | All-Inclusive | Patient-Centered | Timely and Efficient | Assistance With Prescriptions and Insurance Companies | |

| Excerpts | “They have in one building just about everything necessary. All of the diagnostic equipment; they have a blood lab; they have all kinds of scanning equipment. Of course, they have the equipment to test your breathing. Of course, they have the physicians there to meet with you after your tests are completed, so they go over your diagnosis and discuss a treatment plan . . . everything is in one building for all of your pulmonary diagnoses and treatments.” “To me, to be able to go somewhere that they have all of the necessary specialties to provide complete diagnostic and treatment-option discussions, that really should be done in a day because of the psychological impact . . . the more quickly that you can get a definitive diagnosis, to me would be very important.” |

“Very, very integrated and focused on the patient.” “Being a patient-centered facility rather than a doctor-centered facility.” “The idea of doctors being cued in to compassion and not just talking about the data or the interest in data in their research . . . also to remember that these are patients.” |

“I think if I had had a place to go, and no matter how long it took me . . . but just to be able to stay in one spot and be able to get it done and know, ‘Okay. This is it. This is what’s happening’ to me is very important.” “For us, because we fatigue so easily and get so short of breath, the least amount of travel and appointment times would be ideal.” |

“Maybe somebody who would go through insurance or check your insurance for the different medications.” “It would be great if there was somebody that can look into your insurance benefits.” “I think that a good clinic would have a more competent staffing level to deal with prescriptions for medication, prescriptions for oxygen, and prescriptions for rehab.” |

|

| Expanded Access to Care | Communication | Geographic Considerations and Travel | Pulmonary Rehabilitation | Clinical Trials Participation | |

| Excerpts | “I would advise people to sign up for the . . . patient portal, to get familiar with that process, it makes things a lot easier in contacting doctors and/or their staff . . . its just an easy, easy way of communicating and not having to be on the phone for minutes at a time waiting for someone to answer or someone to call you back.” “I just feel like I can always reach out to her and ask her any questions, and she always gets back to me.” |

“Its gonna go always to me location, location, location, you know what I mean? Wherever they’re located at makes it easier. If I can get there within an hour, that’s nice, but if I have to drive 6 hours to get to the place, once again, its just a hard thing.” “I had to go out of state to get any help whatsoever.” “But that could be just because I’m so far and remote from any facility. I’m so far away to the facility.” |

“I think that would be my biggest complaint about any clinic is where is your pulmonary rehab and how can we get people there easy. These people don’t travel well in the first place, and then they have to go so far to get—what I consider is one of the treatments for pulmonary fibrosis, is pulmonary rehab.” “It took me actually 9 months to find a pulmonary rehab that was not too far away from us . . . most of ’em are [1] hour and a half, 2 hours away, which is kinda far when you’re going two to three times a week.” |

“I would love to get into a trial . . . I mean, that’s how we’re gonna beat this thing, you know, and to slow down the progression and to make things better for other people. Trials are extremely important.” “I believe that most patients would be very happy to participate in trials if they were offered that participation in a hope that we might be able to, you know, help make some discoveries that will, if not prevent other people from having the condition in the future, at least to come up with some better treatment options.” |

|

| Comprehensive Support for Living and Coping With Interstitial Lung Disease | Patient Advocate | Disease Education | Counseling and Support Services | Patient Support Groups | Supplemental Oxygen |

| Excerpts | “First of all, they come in and tell that patient that they’re not alone.” “It would be somebody that you would feel comfortable going to with multiple questions . . . that would have access and obviously enough knowledge about the disease to know the next step that you’re looking for or in need of.” “Having somebody who essentially knows you, that maybe periodically would touch base with us if we haven’t been in clinic in a month or two. Even if it’s a phone call saying, ‘Whad’ya need?’ Or, you know, just, ‘Let me know if you need something. I’ll try to find it and tell you where to go and get it.’” “If there was some sort of patient ambassador that people can have where there are so many questions that a patient will have afterwards . . . that coordinate the questions and to be able to pass on information to the patients or the families to get them pointed in the right direction when they have these different questions.” “You always know you can call up this person and whether its getting a doctor’s appointment scheduled, or getting a referral or getting a new medication or medication refill, if it’s questions about insurance . . . to have somebody as a primary point of contact to coordinate all of these different things, whether its them being able to answer the question or just getting you pointed in the right direction to find that answer is something that would be very valuable.” |

“I think on that first visit, there needs to be more information given, like that fact sheet of—you can get an IPF fact sheet. That needs to be handed out.” “Things like where you can buy an oximeter and what oximeter is good to get, things like that just right off the bat are good things to get, and books to read . . . that they can start learning and preparing themselves. If they can be prepared right off the bat with stuff, I think, to me, is an ideal clinic.“ “As soon as you get a diagnosis like IPF, I know that my first inclination is to Google the disease and there’s a lot of bad information out there, inaccurate information, and scary information . . . it’s up to the patient to seek these things out most of the time, as opposed to maybe one center having all these things and not only providing the services but also giving an explanation of why these things are important.” “The most important things they could do would be to make the patient aware of the organizations that exist to help support patients who have ILD.” |

“There would be counsellors, counselling services there because you’re being given a death sentence. That is the biggest shock in the entire world to have that happen.” “There’s got to be some help there, emotional help, as much as the physical-medical aspect of it.” “A psychologist or a therapist. Whatever you wanna call it because, I mean, really and truly, you are filled with emotions of all different kinds. Panic, fear, sadness. You know? Just totally in awe about everything. And your life’s been turned upside down.” “The coordination of mental health . . . as part of the staff too where they can coordinate with the patient to, I guess, understand, cope with, get adjusted to this new way of life and being given this diagnosis.” |

“This is the opportunity to interact very closely with other people who are similarly situated. You know, it’s a great source of support as well as information . . . You can get together on a regular basis with a group of folks, who are similarly situated, and you’ll find it to be a very beneficial just to be able to spend time together and compare notes. That, to me, I think is a very important part of the support that would be provided by this center.” “I think a support group is critical in your area in some way. It doesn’t have to be at your center, but I think also, what I’m hearing more and more is if there could be a period support session just for caregivers, not with the patients attending, ’cause caregivers often face unique circumstances, and sometimes, its helpful for them to share strategies.” |

“Having an advocate to say ‘I’m here to help you get your oxygen, to tell you where’s the best place for you to go. Or, here’s the different places that you can go to get your oxygen, here are the different types of concentrators.’ That stuff, I just had no clue about. I did not know anything about it. I did not know where to go to find the oxygen . . . those things would be so helpful if somebody had some ideas about it and could help.” “Since oxygen is prescribed, it would be nice to be able to get a prescription that would start out with a POC, a pulmonary oxygen concentrator.” “Someone who can get you through the ropes of dragging the equipment through the airport . . . I was having to do all of this by myself because there was nobody to help me.” “One of the things they discussed and I found most beneficial was traveling with the condition and having to drag your equipment along with you.” |

ILD = interstitial lung disease; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Comprehensive Patient-Centered Medical Care

In all five groups, patients and caregivers expressed the desire for comprehensive, patient-centered, and coordinated care center. One male patient with ILD who had undergone a lung transplant succinctly characterized this type of experience: “To have a facility that was totally all-inclusive would be ideal.” Participants expressed the desire for a wide-ranging group of providers and services to be incorporated into an ILD clinic or, at minimum, to be readily available. These included physicians and surgeons, various diagnostic capabilities (laboratory, imaging, pulmonary function testing), multidisciplinary teams for diagnosis, access to all available treatment methods, pulmonary rehabilitation, psychosocial support (eg, counselors, psychologists, social workers), and palliative care. One female participant with connective tissue disease-related ILD stated: “It would be nice to have a building where it’s interdisciplinary where you have access to—when you go you have access to a nurse, a doctor, a respiratory therapist, a nutritionist, somebody to help you with your oxygen, your medications. That would be my ideal . . . just to have access to everybody when you go that day.”

The concept of integrated care was viewed as being particularly important at the time of diagnosis because of the physical toll of travel, numerous appointments, and diagnostic testing in addition to the psychological impact of receiving the initial diagnosis of ILD.

Participants expressed that timely and efficient care was equally important, particularly coordination of follow-up specialist appointments on the same day. Assistance working with insurance companies to avoid delays in care and other necessary treatments (diagnostic testing approval, oxygen prescriptions, medications, and particularly antifibrotics) also was mentioned frequently.

Expanded Access to Care

The ideal ILD clinic described by participants was one that ensured adequate and timely communication, was geographically accessible, and included opportunities to be involved in a range of treatments, specifically pulmonary rehabilitation and clinical trials.

Use of online patient portals, if available, was suggested frequently for ease and timeliness of communication, including results of diagnostic testing, and for questions that were perceived as not needing a physician to answer personally. One suggestion echoed in several groups was to establish a single point of contact within the clinic to improve communication and was summarized by one family caregiver in this way: “If there could be one person in the clinic . . . who could be the primary point of contact ‘cause the doc’s too busy . . . [that] would relieve patients of a lot of aggravation and stress if they could be more unitary kind of point of contact.”

Geographical constraints and accessibility of ILD centers was a concern for participants. Some stated that it was a “luxury” to be close to specialty centers and expressed concern for patients who could not easily access one. Accessibility and travel time were linked with the importance of coordinating appointments and ensuring comprehensive care because of the challenges of traveling numerous times.

Expanded access to care encompassed access to pulmonary rehabilitation and clinical trials participation. Pulmonary rehabilitation was viewed as a necessary but underused treatment option. This was attributed to difficulties with accessibility and travel logistics and to many patients (including some participants) being unaware of its benefits. Receiving care at a center that offered research and clinical trials opportunities also was valued by participants, giving them access to new therapeutics and to “help make discoveries” that would “make things better for other people” in the future.

Comprehensive Support for Living and Coping with ILD

The most consistently voiced topic across the five focus groups was the need for additional support for patients and families. Patients and caregivers believed that the ideal care experience specifically had to include increased disease-state education, availability and use of counseling and support services, patient support groups, and assistance with obtaining, using, and living with supplemental oxygen.

The most commonly expressed need within this theme, and the most frequent suggestion from participants as a way to address the broader support needs described above, was the concept of a “patient advocate.” This phrase was used independently in three of the five focus groups, with the other two groups using terms such as “ambassador” and “personal coach” to describe a similar concept. Patient advocates were seen as necessary personnel within an ILD clinic to ensure that patients’ needs were met. The roles of patient advocates were broad. First and foremost, they were envisioned as providing patient support and information, particularly at the time of diagnosis. One participant expressed, “Having an advocate in the clinic who understands the dynamic of getting hit over the head in the appointment with all of the information that they’ve gotten, just have an advocate be in there to respond to all of the terminology and the questions that the doctor left you with because you didn’t have enough time to ask . . . a translator.”

Advocates were described as a bridge to the clinic, a point person with the necessary breadth and depth of disease-state knowledge to provide additional support and education at the time of diagnosis, to provide resources such as support group information and appropriate online references, and to be the primary point of contact for any patient or caregiver question or need. Advocates were described as a person who could coordinate appointments and “maneuver through . . . the system.” Suggestions for who could perform these myriad roles included a dedicated ILD clinic nurse, respiratory therapists, social workers, case managers, or patient volunteers.

Discussion

This study systematically identified and described the necessary components of an ILD clinic from the vantage point of two distinct groups of ILD experts: ILD specialist physicians and ILD patients and caregivers. Through the Delphi process, we identified personnel, infrastructure, and resource needs, including specifics around a multidisciplinary conference, that are essential to providing care for patients with ILD. Many of the essential items identified are consistent with the PFF CCN requirements to become a designated site.2 Our findings support these criteria, including personnel, availability and timeliness of new patient appointments, multidisciplinary diagnosis, access to support groups, clinical research opportunities, and specific CT imaging capabilities. Additional details that emerged that are not included in the PFF CCN criteria include the level of physician expertise and experience (PFF CCN criteria specify 3 years of postfellowship experience in pulmonary fibrosis to be a center director, but no guidelines for other physicians or providers), additional staff and their roles in the clinic, and the breadth of available ancillary procedures. The focus groups allowed for patients and caregivers to describe a clinic environment that would serve their needs best. In many ways, the experience of and components of the ideal ILD clinic described in the focus groups mirrored the essential items identified through the Delphi process (Fig 3). Two areas emphasized in the focus groups that were not identified from the Delphi process were improved access to communication and more explicit support services, such as availability of psychologists or counselors, and direct education and support for supplemental oxygen use. Findings from the focus groups are similar to what has been previously described as the “unmet needs” of ILD patients.6, 7, 8, 9 Collectively, incorporating results from both the Delphi and the focus groups may help to inform future efforts at establishing best practices at the CCN and other ILD specialty clinics.

Figure 3.

Diagram showing essential items for an ILD clinic from patient, caregiver, and physician experts. Despite different methods of data acquisition and perspectives of clinical care, the essential items identified by patients and caregivers in the focus groups showed multiple parallels to the essential items identified by physicians through the Delphi process. ILD = interstitial lung disease.

Although a great deal of literature supports the gold standard of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis,10 the resultant improved diagnostic accuracy,11 and the impact on patient management,12 the results from this study may represent a first step toward understanding essential components of care delivery to improve outcomes or care experiences for patients with ILD. This could be modeled after the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation practice of implementing standardized care across centers and using benchmarks to advance best practices that have been shown to improve patient outcomes.13

This study had limitations. The Delphi items were developed through interviews with eight site directors and may not represent the full breadth of items that other directors might have identified as important, although participants were allowed to add items in the first round. Because only PFF CCN sites were invited to participate in the Delphi process, the results inherently are influenced by the existing CCN criteria (eg, requirement for research opportunities, support group, and multidisciplinary conference), and therefore may not be generalizable to other clinics that provide care to patients with ILD, including those outside of the United States. Focus group participants initially were recruited in person at the PFF 2019 Summit. This is a highly motivated, self-selected group of patients and caregivers who are aware of the PFF and are physically and financially able to travel. Subsequent recruitment was completed through the assistance of the PF Warriors support group, which reaches a broad international audience. Including participants recruited in both manners may have mitigated some of the bias of patients already involved in the PFF.

Further, the data were collected before the current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 global pandemic. Given that patients with ILD are considered high risk for severe disease, many ILD clinics rapidly adopted telehealth services to provide ongoing care. In personal communication with the PFF CCN, telehealth access increased from 8% at the time of our original survey to approximately 98% during the month of June 2020. Although many providers and patients are still adjusting to providing and receiving care in this format, this method may be one way to address meaningfully and expand access to patients who otherwise are limited in their access to specialized centers. The shift to telehealth also has required many patients not previously using portals to become familiar with them as a means of communication and care delivery , improving timeliness of communication. Leveraging virtual applications in other areas (eg, education, support groups, pulmonary rehabilitation) also may help to address some of the needs identified in this study.

Future work should focus on understanding the process and limitations for the widespread implementation of these essential items across clinics that care for ILD patients, like the PFF CCN. Financial, geographic, and other resource constraints, including the number of experienced ILD physicians available, may limit the implementation of these findings. Further, work should be carried out to demonstrate the impact of implementing these measures in the care and outcomes of patients with ILD, because this may help to convince payors of the value of properly resourced ILD clinics. This also would allow us as an ILD community to understand better what components may influence long-term outcomes for patients. We also should strive to address the needs of patients particularly in the form of coordinated care, communication, and patient advocates (eg, ILD nurses) to provide support, education, and patient-centered care.

Interpretation

ILD patients require subspecialized, comprehensive, multidisciplinary care. The essential components of an ILD clinic identified in our study are well aligned between clinical experts and patients with an emphasis on personnel, infrastructure, resources, and a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis. Future research assessing the impact of these essential components of an ILD clinic on patient outcomes across the PFF CCN would inform best practices for the broader ILD community.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: C. H., B. A. G., and J. S. L. conceived and designed the study. C. H. and B. A. G. acquired the data. B. A. G., C. H., M. M., P. .B, G. C., and J. S. L. analyzed and interpreted the data. B. A. G., C. H., M. M., S. M., P. B., G. C., and J. S. L. were involved substantially in the writing or revision of the article, or both. J. S. L. was responsible for content of the manuscript, including data and analysis.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: P. B. serves as the Senior Vice President of Research and Programs for the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation; G. P. C. has served as site principle investigator or collaborator in industry-sponsored clinical trials (Genzyme and Bristol-Myers-Squibb), serves as the Chief Medical Officer of the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, and has served as an advisor to InterMune and Boehringer Ingelheim. J. S. L. has received personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Calapagos, and Eleven P15 outside the submitted work and is the Senior Medical Advisor for Research and Health Care Quality at the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation. None declared (B. A. G., C. H., M. M., S. M.).

∗PFF CCN Delphi Collaborators: Rodeo Abrencillo, Rebecca Bascom, Mary Beth Scholand, Nitin Bhatt, Amy Case, Sachin Chaudhary, Daniel Culver, Sonye Danoff, Alpa Desai, Daniel Dilling, Craig Glazer, Mridu Gulati, Nishant Gupta, Mark Hamblin, Nabeel Hamzeh, Tristan Huie, Hyun Kim, Christopher King, Maryl Kreider, Peter Lacamera, Lisa Lancaster, Tracy Luckhardt, Yolanda Mageto, Robert Matthew Kottman, James McCormick, Borna Mehrad, Prema Menon, Sydney Montesi, Joshua Mooney, Doug Moore, Teng Moua, Anoop Nambiar, Justin Oldham, Divya Patel, Tessy Paul, Rafael Perez, Anna Podolanczuk, Murali Ramaswamy, Ryan Boente, Mohamed Saad, Nathan Sandbo, Thomas Schaumberg, Shelley Schmidt, Barry Shea, Adrian Shifren, Mary Strek, Krishna Thavarajah, Nevins Todd, Srihari Veeraraghavan, Stephen Weight, Paul Wolters, and Joseph Zibrak.

Other contributions: The authors thank Jay Graney, MA, for his Microsoft Excel expertise and assistance, the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, the Care Center Network site directors who participated in the Delphi process, Bill Vick and the PF Warriors community, and all of the participants of the focus groups for sharing their time and invaluable perspectives.

Additional information: The e-Appendixes and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

Drs Graney and He contributed equally to this manuscript.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health [Grant HL138131].

Contributor Information

Joyce S. Lee, Email: Joyce.lee@cuanschutz.edu.

PFF CCN Delphi Collaborators:

Rodeo Abrencillo, Rebecca Bascom, Mary Beth Scholand, Nitin Bhatt, Amy Case, Sachin Chaudhary, Daniel Culver, Sonye Danoff, Alpa Desai, Daniel Dilling, Craig Glazer, Mridu Gulati, Nishant Gupta, Mark Hamblin, Nabeel Hamzeh, Tristan Huie, Hyun Kim, Christopher King, Maryl Kreider, Peter Lacamera, Lisa Lancaster, Tracy Luckhardt, Yolanda Mageto, Robert Matthew Kottman, James McCormick, Borna Mehrad, Prema Menon, Sydney Montesi, Joshua Mooney, Doug Moore, Teng Moua, Anoop Nambiar, Justin Oldham, Divya Patel, Tessy Paul, Rafael Perez, Anna Podolanczuk, Murali Ramaswamy, David Roe, Mohamed Saad, Nathan Sandbo, Thomas Schaumberg, Shelley Schmidt, Barry Shea, Adrian Shifren, Mary Strek, Krishna Thavarajah, Nevins Todd, Srihari Veeraraghavan, Stephen Weight, Paul Wolters, and Joseph Zibrak

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Nathan S.D., Shlobin O.A., Weir N. Long-term course and prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the new millennium. Chest. 2011;140(1):221–229. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Working together to improve patient outcomes: PFF Care Center Network. Updated March 1, 2019. Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation website. https://www.pulmonaryfibrosis.org/docs/default-source/medical-community-documents/pff-care-center-criteria-2019-v-03-updated_03-01-2019.pdf?sfvrsn=a02d918d_2 Accessed June 30, 2020.

- 3.Diamond I.R., Grant R.C., Feldman B.M. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hennink M.M., Kaiser B.N., Weber M.B. What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qual Health Res. 2019;29(10):1483–1496. doi: 10.1177/1049732318821692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders B., Sim J., Kingstone T. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morisset J., Dube B.P., Garvey C. The unmet educational needs of patients with interstitial lung disease. Setting the stage for tailored pulmonary rehabilitation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(7):1026–1033. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201512-836OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramadurai D., Corder S., Churney T. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: educational needs of health-care providers, patients, and caregivers. Chron Respir Dis. 2019;16 doi: 10.1177/1479973119858961. 1479973119858961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramadurai D., Corder S., Churney T. Understanding the informational needs of patients with IPF and their caregivers: ‘You get diagnosed, and you ask this question right away, what does this mean? BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J.Y.T., Tikellis G., Corte T.J. The supportive care needs of people living with pulmonary fibrosis and their caregivers: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(156):190125. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0125-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travis W.D., Costabel U., Hansell D.M. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flaherty K.R., King T.E., Jr., Raghu G. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):904–910. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-147OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jo H.E., Glaspole I.N., Levin K.C. Clinical impact of the interstitial lung disease multidisciplinary service. Respirology. 2016;21(8):1438–1444. doi: 10.1111/resp.12850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle M.P., Sabadosa K.A., Quinton H.B., Marshall B.C., Schechter M.S. Key findings of the US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s clinical practice benchmarking project. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(suppl 1):i15–i22. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.