Introduction

Teratomas are tumours consisting of different cell types derived from more than one germ layer. Apart from the gonads, teratomas can also be found in midline structures [1]. Coccyx is the most common site of extragonadal teratoma. These tumours originate ventral to the sacrum and may grow posteroinferiorly into the gluteal area or anterosuperiorly into the lesser pelvis. Most of the sacrococcygeal teratoma in adults presents as intrapelvic masses, in contrast to neonates where more than 90% present as extrapelvic masses.

Case Report

A 20-year-old unmarried female, presented with gradually increasing abdominal pain and distension for 15 days. On examination, a firm impacted pre-sacral mass around 15 × 10 × 10 cm was felt in POD. Routine investigations were within normal limits.

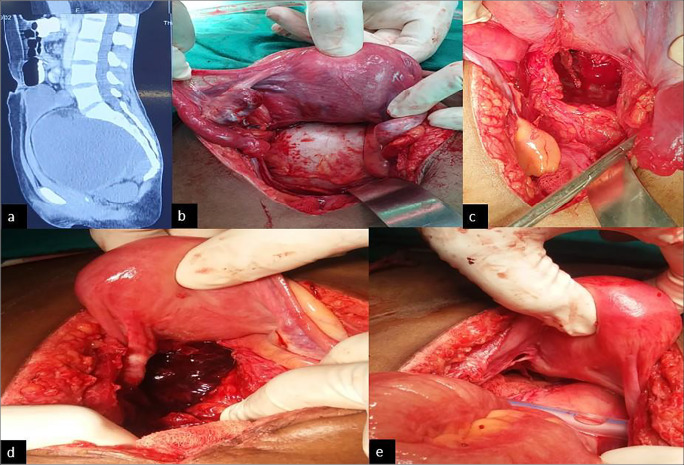

Contrast-enhanced CT revealed an abdomino-pelvic mixed density lesion around 15 × 11 × 11 cm in pre-sacral space displacing the uterus and rectosigmoid anteriorly, containing a fat-density area within, suggestive of ovarian teratoma (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Abdomino-pelvic CT scan showing a mixed density mass in the presacral space displacing the rectosigmoid anteriorly. b Intraoperative image of the presacral mass, pushing uterus anteriorly and rectum laterally. ) The space formed after removal of the cyst from presacral space. d Haematoma formation on 3rd post-operative day after excision of the teratoma. e Prophylactic packing of the dead space after removal of haematoma and keeping the drain

The serum a-fetoprotein and human chorionic gonadotropin levels were normal. LDH was raised at 580. Patient underwent exploratory laparotomy and cystectomy. Findings at surgery were a cystic mass, around 15 × 10 × 10 cm displacing the lower third of the rectum anterolaterally and adherent to the coccyx (Fig. 1b). The cyst exuded sebaceous material. The rectum was dissected off the pre-sacral fascia and the tumour dissected off the coccyx and excised (Fig. 1c). Homeostasis was achieved and the pelvic floor was reconstructed. On post-operative day 3, patient had secondary haemorrhage and developed severe anaemia. Emergency re-laparotomy and bilateral internal iliac artery ligation with pelvic packing with ribbon gauzes were done (Fig. 1d, e). After 72 h of observation, the packing was removed and patient recovered well. Histopathology report confirmed mature cystic teratoma. Patient was kept on regular follow-up.

Discussion

SCT is the most common congenital neonatal tumour with incidence of approximately 1 in 35,000 to 1 in 40,000 live births [2] with female to male ratio being 4:1 [3]. It is very rare in adults with less than a hundred cases reported in literature [4] and the incidence being 1 in 40,000 to 1 in 63,000 with female preponderance of 3:1 [5]. Based on their histological features, SCTs are classified into three categories: mature, immature and malignant. Mature teratoma is benign and contains obvious epithelial-lined structures along with mature cartilage and striated or smooth muscle. Immature teratomas contain primitive mesoderm, endoderm or ectoderm mixed with more mature elements. Malignant teratomas have frankly malignant tissue of germ cell origin in addition to mature and/or embryonic tissues.

Malignant transformation has been found in approximately 1% of teratoma patients comprising squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, sarcoma and other malignancies [3]. The risk of infection is 20–30%.

Teratomas have their origin in totipotential cells, which are normally present in the ovary and testes and are sometimes abnormally present in sequestered midline embryonic rests, which are formed as a result of the caudal migration of these cells to rest in the coccygeal region. Teratomas are found, in decreasing order of frequency, in the gonads (ovaries and testes), the anterior mediastinum, the retroperitoneal space, the pre-sacral and coccygeal areas, pineal and other intracranial sites, the neck and abdominal viscera other than the gonads [6].

Other theories include nonsexual reproduction of germ cells within the gonads or in extragonadal sites; ‘wandering’ germ cells of non-parthenogenetic origin left behind during the migration of embryonic germ cells from yolk sac to gonad; or origin in other totipotential embryonic cells [7, 8]. One theory suggests that teratomas might be the result of twinning attempts [9, 10].

Familial form of pre-sacral teratomas has also been reported. It is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern and is associated with a sacral defect, equal sex prevalence and low incidence of malignancy.

Altman et al. classifies sacrococcygeal teratomas. They marked out 4 categories by location. Type I is predominantly external tumours with minimal pre-sacral component. Type II presents externally but with significant intrapelvic extension. Type III is still apparent externally but predominantly a pelvic mass extends into the abdomen. This is the most common type in adults. Type IV is a pre-sacral mass with no external presentation [11].

Most adult patients are asymptomatic with the mass being diagnosed incidentally in a digital rectal examination or on radiological examination as a retro-rectal mass. Large masses can give rise to symptoms of mass effect such as constipation, pain in sacrococcygeal region, bladder dysfunction, venous engorgement of lower limbs and neurological symptoms.

The differential diagnosis of SCT in adults includes chordoma, meningocele, giant cell tumour of sacrum, pilonidal cysts, rectal duplication cysts or anal gland cysts osteomyelitis of sacrum, fistula with pre-sacral extension and abscess formation, post-injection granuloma and tuberculosis [12].

Serum markers are not helpful in diagnosis [13]. Calcifications in the coccygeal region in the roentgenogram or an anterior displacement of the rectum in the barium enema are suggestive of SCT [14]. CT scan and MRI are helpful for better characterization and pre-operative staging respectively [15].

Treatment of choice is complete surgical excision, which generally has a very good prognosis. Pre-operative embolization can be considered in large tumours to reduce intra-operative haemorrhage. Tumour can be accessed by either transabdominal approach or the transperineal route using the jack-knife position or a combined approach. In case of involvement of coccyx, its excision may be necessary because the bone may contain a nidus of pluripotent cells with a risk of recurrence [16]. And if excision of the coccyx is considered, the most appropriate route is the trans-sacral or the perennial route.

Massive bleeding is the major surgical morbidity for the surgical excision of SCT [17]. Transcatheter arterial embolization may be useful for reducing blood loss during the excision of a large-sized tumour [18]. Other surgical morbidities include bladder dysfunction, faecal incontinence and dysesthesia, resulting from injury to pelvic splanchnic nerves.

Conclusion

Adult SCTs are rare and should be suspected in case of pre-sacral pelvic mass. It is often found incidentally, mostly being asymptomatic. Imaging studies are useful in identifying the exact location and character of the tumour. Prognosis depends on the extent of surgical resection and histopathological findings of tumour. Long-term survival is possible with adequate resection of the tumour.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cho SH, Hong SC, Lee JH, et al. Total laparoscopic resection of primary large retroperitoneal teratoma resembling an ovarian tumor in an adult. J Minim Invasive Gynaecol. 2008;15:384–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schropp KP, Lobe TE, Rao B, Mutabagani K, Kay GA, et al. Sacrococcygeal teratomas: the experience of four decades. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90563-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golas MM, Gunawan B, Raab BW, Füzesi L, Lange B. Malignant transformation of an untreated congenital sacrococcygeal teratoma: a amplification at 8q and 12p detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;197(1):95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bull J, Jr, Yeh KA, McDonnell D, Caudell P, Davis J. Mature presacral teratoma in an adult male: a case report. Am Surg. 1999;65:586–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paramythiotis D, Papavramidis T, Michalopoulos A, et al. Chronic constipation due to presacral teratoma in a 36-year-old woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:23. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel RM, Elkins RC, Fletcher BD. Retroperitoneal teratoma. Cancer. 1968;22:1068–1073. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196811)22:5<1068::aid-cncr2820220525>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audet IM, Goldhahn RT, Dent TL. Adult sacrococcygeal teratomas. Am Surg. 2000;66(1):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahour GH. Saccrococcygeal teratomas. CA Cancer J Clin. 1988;38(6):362–367. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.38.6.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park YJ. Multiple presacral teratomas in an 18-year-old Girl. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011;27(2):90–93. doi: 10.3393/jksc.2011.27.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keslar P, Buck J, Suarez E. From the archives of the AFIP. Radio Graphics. 1994;14:607–620. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.14.3.8066275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altman RP, Randolph JG, Lilly JR. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: American Academy of Pediatrics Surgical Section Survey-1973. J Pediatr Surg. 1974;9(3):389–398. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(74)80297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miles RM, Stewart GS., Jr Sacrococcygeal teratomas in adult. Ann Surg. 1974;179:676–683. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197405000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tolins SH, Cooper P. Presacral teratoma. Am J Surg. 1968;115(5):734–737. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(68)90114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng EW, Porcu P, Loehrer P. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in adults: case reports and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1999;86(7):1198–1202. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1198::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miles RM, Stewart S. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in adults. Ann Surg. 1974;179(5):676–683. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197405000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keslar PJ, Buck JL, Suarez ES. Germ cell tumors of the sacrococcygeal region: radiologicpathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1994;14(3):607–620. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.14.3.8066275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson PJ, Wise KB, Merchea A, Cheville JC, Moir C, et al. Surgical outcomes in adults with benign and malignant sacrococcygeal teratoma: a single-institution experience of 26 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:851–857. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang HL, Chen KW, Wang GL, Lu J, Ji YM, Liu JY, Wu GZ, Gu Y, Sun ZY. Pre-operative transarterial embolization for treatment of primary sacral tumors. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:1280–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]