Introduction

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) constitutes approximately 10% of all soft tissue sarcoma [1]. In the gynecological tract, LMS most commonly occurs in the uterus [2]. Broad ligament LMS is very rare with less than 30 cases reported in English literature. Gardner et al. proposed the definition of tumor of broad ligament as “Tumors occurring on or in the broad ligament and completely separated from and in no way connected with either the uterus or the ovary” [3]. LMS has a varied prognosis but in general is aggressive with 5-year survival of 25–76% [4]. We hereby report a rare case of this malignant tumor in a premenopausal female.

Case Report

A 40-year old premenopausal female with 2 living children presented with symptoms of dull abdominal pain and abdominal distension of 7 months duration. There was no significant gynecological or past medical history. There were no complaints of menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, or dysmenorrhoea. General physical examination revealed a vague ill-defined, non-tender lump palpable in the left side of the lower abdomen. All her hematological and biochemical parameters were within normal limits. An ultrasound examination of the abdomen and pelvis showed a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass 11.59*8.77*8.03 cm in the left adnexa and pouch of Douglas. The uterus was normoechoic with normal thickness of endometrium and displayed anteriorly. MRI pelvis revealed an abdomino-pelvic mass with lobulated margins and prominent central necrosis/cystic areas (20*15 cm) arising from the left adnexa and extending upwards into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 1). The serum CA-125, CEA, CA19.9, and LDH were within normal limits. She underwent exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperatively, there was a 20*20 cm multilobulated mass arising from the left broad ligament. The mass was separate from the uterus and left ovary. Bilateral ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, and urinary bladder were normal. She underwent left broad ligament mass excision, total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), and peritoneal wash cytology. The cut section of the mass showed areas of hemorrhage and whirling. The cut surface of the uterus and both ovaries were unremarkable. Microscopic examination of the mass showed a malignant spindle cell tumor with nuclear and cellular pleomorphism along with the areas of coagulative necrosis. The tumor cells had pleomorphic, vesicular coarse chromatin with conspicuous nucleoli. Mitosis was brisk at about 12–15/10 HPFs. There were interspersed areas of necrosis (Fig. 2). Sections from both ovaries and uterus were unremarkable. The uterus shows secretory endometrium and chronic cervicitis. Peritoneal washing was within normal limit.

Fig. 1.

MRI showing the large mass in pelvis

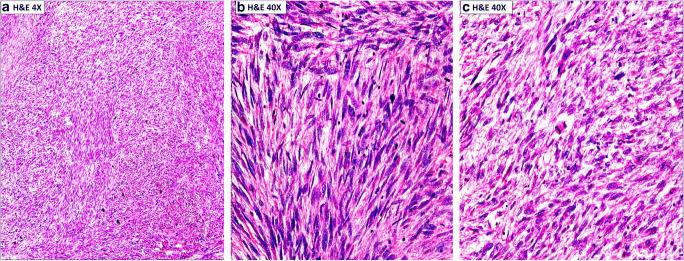

Fig. 2.

A- Low magnification showing a malignant mesenchymal tumor demonstrating smooth muscle differentiation with interlacing bundles and fascicles of pleomorphic spindle cells intersecting at right angles. B and C- Higher magnification illustrating differentiated smooth muscles cells with some nuclear atypia, blunt ended nuclei with eosinophilic cytoplasm. Occasional cells have perinuclear vacuoles and atypical mitotic figures

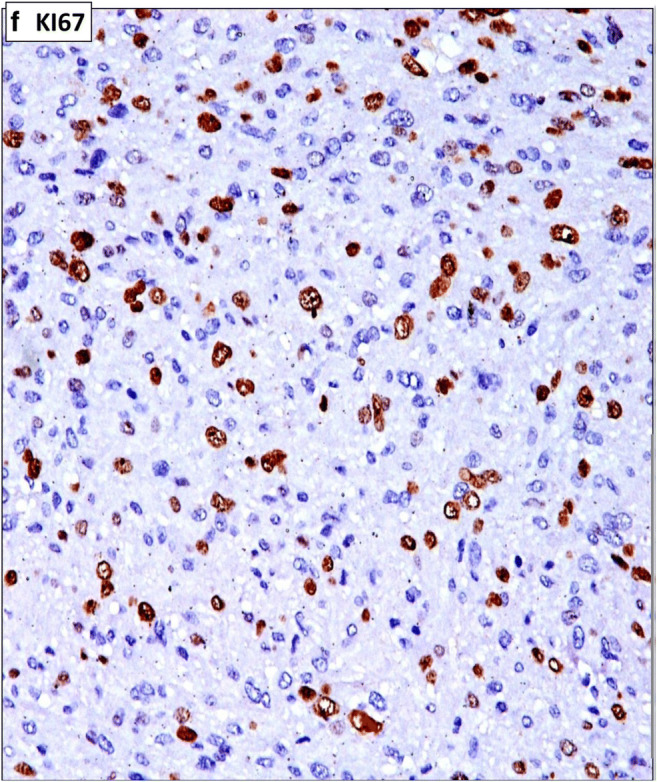

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies showed the tumor cells to be positive for smooth muscle actin (Fig. 3), desmin (Fig. 4), and vimentin. The ki67 index was high (Fig. 5). The cells were negative for PanCK, CD117, S-100, and CD68. Based on these morphological and IHC analyses, a diagnosis of primary LMS of left Broad Ligament—Grade II (intermediate) as per FNCLCC (French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group) grading system was made.

Fig. 3.

The tumor are diffusely immunopositive (Cytoplasmic) for smooth muscle actin (SMA)

Fig. 4.

The tumors are diffusely immunopositive (Cytoplasmic) for Desmin

Fig. 5.

Showing high ki67 proliferative index

Post-operative recovery was uneventful, and a repeat thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT scan did not show any residual disease. Because of an intermediate grade LMS with no residual disease, the patient received 6 cycles single-agent doxorubicin adjuvant chemotherapy for six cycles followed by adjuvant pelvic external beam radiotherapy 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions over five and half weeks. The patient is on regular follow-up and is clinico-radiologically disease free for the last 2 years.

Discussion

Primary LMS originating in the broad ligament is a rare neoplasm. This tumor occurs commonly in postmenopausal women, and only few cases in younger age group have been reported. The clinical manifestations of the cases are nonspecific including abdominal pain, distension, nausea, constipation, and malaise [5–31]. As there are very few case reports of primary broad ligament LMS, the histological diagnostic and grading criteria, and the staging and management used are similar to uterine LMS. The microscopic diagnosis of LMS has evolved gradually over the years. Presently, the diagnosis of LMS relies on the presence of three criteria: coagulative tumor cell necrosis, cytologic atypia, and mitotic activity. Zaloudek and Hendrickson proposed that the presence of coagulative necrosis itself is enough for the diagnosis of LMS [32]. In the absence of cell necrosis, the diagnosis of LMS needs to diffuse moderate to severe cellular atypia and more than 10 mitoses/10 HPFs [33]. Various authors have refined and redefined the diagnostic criteria that have been used for years and have made attempts to correlate these findings with clinical outcome. The systems used for grading of soft tissue sarcomas are the NCI (National Cancer Institute) and FNCLCC systems. We used the FNCLCC grading system which is based on a score obtained by evaluating three parameters: tumor differentiation, mitotic rate (0–9, 10–19, and > 20 mitoses/10 HPFs), and the amount of tumor necrosis (< 50% tumor necrosis and > 50% tumor necrosis). According to both these systems, LMS is classified as low, intermediate, and high grade. The present case was classified as intermediate grade LMS.

There is a wide variation in the management practices of this uncommon tumor, but initial treatment is usually excision of mass, total abdominal hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as depicted in Table 1. Pelvic lymph node dissection is debatable and has not been consistently shown to improve survival in uterine LMS [4, 34]. Our patient did not undergo lymph node dissection keeping in mind lack of evidence and risk of lymphedema [35]. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy is usually extrapolated from that of uterine LMS. The results of adjuvant radiotherapy in the treatment of uterine LMS are conflicting with some studies showing improvement in local control [36], while others are not showing any impact [37]. These studies have been either retrospective in nature or underpowered prospective studies due to the rarity of the disease. Keeping in mind the local failure rates of 30–40% [38] in different studies, we delivered adjuvant radiotherapy to the pelvis. Data on adjuvant chemotherapy is also conflicting. There is presently no completed randomized adequately powered study on uterine LMS to determine the role of adjuvant chemotherapy. Some studies have shown small improvements in disease-free survival with chemotherapy. Our patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with a single-agent doxorubicin as this drug is well tolerated and been shown to have good response rates in metastatic LMS [39].

Table 1.

Reported cases of broad ligament Leiomyosarcoma

| No | Author | Year | Age (Years) | Diameter (cm) | Preop diagnosis | Mitoses (per 10 hpf) | Surgery | Adjuvant therapy | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ahmed F et al. [5] | 2019 | 62 | 28 | Uterine sarcoma | NA | TAH + BSO + Resection of mass | RT | NED at 6 months |

| 2 | Chaichian et al. [6] | 2016 | 55 | Retroperitoneal tumor | NA | TAH + BSO + OM + PLN + PAND | RT, CT | NED >9 months | |

| 3 | Nishat et al. [7] | 2015 | 58 | Ovarian cancer | 5 | BSO + OM + PLN + PAND | – | ||

| 4 | Devika Gupta et al. [8] | 2015 | 41 | 10.3 | Adnexal tumor | 12–14 | TAH + BSO | CT | AWD 2 months |

| 5 | Makihara et al. [9] | 2014 | 61 | 18 | Ovarian cancer BLLMS | NA | Resection (?) of broad ligament LMS | NA | |

| 6 | Akhavan A [10] | 2013 | 60 | 10 | ? | 10 | TAH + BSO | RT | Metastases to abdominal wall 5 years |

| 7 | Kolusari et al. [11] | 2009 | 35 | 18 | pelvic mass | > 20 | TAH + BSO | CT + RT | NED > 12 month |

| +OM | |||||||||

| +PLN + PAND | |||||||||

| 8 | Duhan et al. [12] | 2009 | 45 | 24 | NA | > 10 | Resection+BSO | CT | NED > 15 months 5 |

| 9 | Papachat zopoulos et al. [13] | 2009 | 38 | 20 | fibroid | > 10 | TAH + BSO | – | DOD 8 months |

| 10 | Bouraoui S et al. [14] | 2008 | 45 | NA | Broad ligament leiomyo sarcoma | NA | resection | CT | NED >15 months |

| 11 | Falconi et al. [15] | 2006 | 52 | NA | NA | NA | TAH + BSO | NA | AWD 117 months |

| 12 | R Murialdo et al. [16] | 2005 | 53 | ? | Broad ligament leiomyosarcoma | <10 | TAH + BSO | None | NED 13 months |

| 13 | Ben Amara et al. [17] | 2005 | 49 | 23 | ovarian cancer | 7 | TAH + BSO + OM | – | DOD 5 month |

| 14 | El-Idrissi & Fadli [18] | 2004 | 52 | 12.5 | NA | NA | TAH + BSO | – | DOD 3 months |

| 15 | Kir et al. [19] | 2003 | 35 | 17 | NA | 15–20 | TAH + BSO + PLN | – | NA |

| 16 | Shah et al. [20] | 2003 | 87 | 20 | ovarian cancer | 30–40 | TAH + BSO + OM | – | DOD 2 M |

| 17 | Agarwal et al. [21] | 2003 | 55 | 14 | NA | >10 | TAH + BSO | CT | NED > 12 months |

| 18 | Pekin et al. [22] | 2000 | 56 | 11 | ovarian tumor | 14 | TAH + BSO | – | NED > 25 months |

| 19 | Cheng et al. [23] | 1995 | 59 | 7 | NA | > 10 | TAH + BSO | – | NED > 12 months |

| 20 | Lee et al. [24] | 1991 | 65 | 16. 4 | fibroid | > 10 | STH + BSO | CT | AWD > 26 months |

| 21 | Lee et al. [24] | 1991 | 36 | 35 | ovarian cancer | > 10 | TAH + BSO | CT | AWD > 33 months |

| 22 | Shimm & McDonough et al. [25] | 1987 | 31 | 9 | NA | 8 | Resection | RT | AWD 30 months |

| 23 | Herbold et al. [26] | 1983 | 73 | 15 | NA | 21 | TAH + BSO | – | DOD 1 month |

| 24 | Raj-Kumar [27] | 1982 | 70 | 10 | NA | < 10 | Resection | – | NED > 24 months |

| 25 | DiDomenico et al. [28] | 1982 | 48 | 11 | NA | 10.5 | TAH + BSO | – | NED > 21 months |

| 26 | Weed & Podger [29] | 1976 | 50 | 11 | NA | NA | TAH + BSO | – | DOD 19 months |

| 27 | Ullman & Roumell [30] | 1973 | 50 | 11 | NA | NA | TAH + BSO | NA | |

| 28 | Lowel & Karsh [31] | 1968 | 50 | 11 | NA | 0–4 | TAH + BSO | – | NED > 12 months |

*NED: No evidence of disease; DOD: Died of disease; AWD: Alive with disease; TAH: Total abdominal hysterectomy; BSO: Bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy; STH: Sub-total hysterectomy; OM: Omentectomy; PLN: Pelvic lymph node dissection; PAND: Para-aortic node dissection

Data on uterine LMS shows that among those patients who recur, > 65% fail at distant sites like the lungs, abdomen, and liver [38]. Close follow-up is therefore necessary. We followed up our patient with 3 monthly imaging including CT of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis for the first 18 months followed by 6 monthly imaging. The patient is at present on regular follow up with no evidence of recurrence.

Conclusion

Broad ligament LMS is rare. Complete surgical resection with TAH and BSO followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be considered in treatment.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Informed Consent

Obtained from participant in the presence of two neutral witnesses.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sumit Kumar, Email: sumitkumar1223@gmail.com.

Prashanth Giridhar, Email: prashanth.jipmer@gmail.com.

Shalini Verma, Email: shalini.verma.hp@gmail.com.

Ravi Hari Phulware, Email: ravipaarti@gmail.com.

Neena Malhotra, Email: neenamaltra83@yahoo.com.

Ritesh Kumar, Email: riteshkr9@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Ducimetière F, Lurkin A, Ranchère-Vince D, Decouvelaere AV, Péoc'h M, Istier L, Chalabreysse P, Muller C, Alberti L, Bringuier PP, Scoazec JY, Schott AM, Bergeron C, Cellier D, Blay JY, Ray-Coquard I. Incidence of sarcoma histotypes and molecular subtypes in a prospective epidemiological study with central pathology review and molecular testing. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e20294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks SE, Zhan M, Cote T, Baquet CR. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of 2677 cases of uterine sarcoma 1989–1999. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93(1):204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner GH, Greene RR, Peckham B. Tumors of the broad ligament. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1957;73(3):536. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)37427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts ME, Aynardi JT, Chu CS. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: a review of the literature and update on management options. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151(3):562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed F, Pounds R, Teo HG, et al. En bloc resection of the external iliac vein along with broad ligament leiomyosarcoma: a case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2019;23:e00131. doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2019.e00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaichian S, Mehdizadehkashi A, Tahermanesh K, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament with fever presentation: a case report and review of literature. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(4):e33892. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.33892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishat A, Monali P, Anees A, et al. Broad ligament leiomyosarcoma a diagnostic challenge: case report and review of literature. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2015;5(12):181–185. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta D, Singh G, Gupta P, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: a case report with review of literature. Human Pathol Case Rep. 2015;2(3):59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makihara N, Maeda T, Ebina Y, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: a case report with CT and MRI images. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2014;35(2):174–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhavan A (2013) The broad ligament leiomyosarcoma metastasis to the abdominal wall. J Nucl Med Radiat J Nucl Med Radiat Ther 4(6):13–15

- 11.Kolusari A, Ugurluer G, Kosem M, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30(3):332–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duhan N, Singh S, Kadian YS, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of broad ligament: case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(5):705–708. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0777-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papachatzopoulos S, Theodoridis TD, Zafrakas M, et al. Broad ligament leiomyosarcoma in a premenopausal nulliparous woman: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30(4):452–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouraoui S, Blel A, Azouz H, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: a case report and literature review. Tunis Med. 2008;86(7):719–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falconi M, Crippa S, Sargenti M, et al. Pancreatic metastasis from leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament of the uterus. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(1):94–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70543-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murialdo R, Usset A, Guido T, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: a case report and review of literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15(6):1226–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben AF, Jouini H, Nasr M, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of broad ligament. Tunis Med. 2007;85(7):591–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Idrissi F, Fadli A. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament. Presse Med. 2004;33(15):1004–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(04)98823-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kir G, Eren S, Akoz I, Kir M. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament arising in a pre-existing pure neurilemmoma-like leiomyoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003;24(6):505–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah A, Finn C, Light A. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90(2):450–452. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal U, Dahiya P, Sangwan K. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament mimicking as ovarian carcinoma—a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;269(1):55–56. doi: 10.1007/s00404-002-0418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pekin T, Eren F, Pekin O. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: case report and literature review. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21(3):318–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng WF, Lin HH, Chen CK, Chang DY, Huang SC. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56(1):85–89. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JF, Yang YC, Lee YN, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament—report of two cases. Chin Med J. 1991;48:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimm DS, McDonough JF. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament: report of a case. Gynecol Oncol. 1987;26(1):123–126. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(87)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbold D, Fu Y, Silbert S. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament. A case report and literature review with follow up. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7(3):285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raj Kumar G. Leiomyosarcoma of probable ovarian or broad ligament origin. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1982;89(4):327–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1982.tb04706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiDomenico A, Stangl F, Bennington J. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament. Gynecol Oncol. 1982;13(3):412–415. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(82)90080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weed JC, Jr, Podger K. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament coincident with ductal carcinoma of the breast. South Med J. 1976;69(10):1379–1380. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197610000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ullman AS, Roumell TL. A case report. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament. Mich Med. 1973;72:411–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowell DM, Karsh J. Leiomyosarcoma of the broad ligament. A case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1968;32:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaloudek CJ, Hendrickson MR, Soslow RA. Mesenchymal tumors of the uterus. In: Kurman RJ, Ellenson LH, Ronnett BM, editors. Blaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract. Boston: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toledo G, Oliva E. Smooth muscle tumors of the uterus: a practical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(4):595–605. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-595-SMTOTU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kapp DS, Shin JY, Chan JK. Prognostic factors and survival in 1396 patients with uterine leiomyosarcomas: emphasis on impact of lymphadenectomy and oophorectomy. Cancer. 2008;112(4):820–830. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beesley VL, Rowlands IJ, Hayes SC, Australian National Endometrial Cancer Study Group et al. Incidence, risk factors and estimates of a woman's risk of developing secondary lower limb lymphedema and lymphedema-specific supportive care needs in women treated for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gadducci A, Landoni F, Sartori E, Zola P, Maggino T, Lissoni A, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: analysis of treatment failures and survival. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62(1):25–32. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed NS, Mangioni C, Malmstrom H, et al. Phase III randomised study to evaluate the role of adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy in the treatment of uterine sarcomas stages I and II: an European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynaecological Cancer Group study (protocol 55874) Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(6):808–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gadducci A, Landoni F, Sartori E, Zola P, Maggino T, Lissoni A, Bazzurini L, Arisio R, Romagnolo C, Cristofani R. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: analysis of treatment failures and survival. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62(1):25–32. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Judson I, Radford JA, Harris M, Blay JY, van Hoesel Q, le Cesne A, van Oosterom A, Clemons MJ, Kamby C, Hermans C, Whittaker J, Donato di Paola E, Verweij J, Nielsen S. Randomised phase 2 trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (DOXIL/CAELYX) versus doxorubicin in the treatment of advanced or metastatic STS: a study by the EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:870–877. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]