Introduction

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) is a rare uterine neoplasm accounting for 0.2% of all uterine malignancies and around 15% of all uterine sarcomas. ESS is a malignant tumor which originates from invasive proliferation of cells that resemble stromal cells of the normal proliferative endometrium. Patients typically present with abdominal pain and uterine bleeding. Based on their biologic behavior and molecular aberrations, the latest World Health Organization guideline (WHO 2014) classifies the endometrial stromal tumors into endometrial stromal nodule, low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS), high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS), and undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma (UES) [1, 2].

LG-ESSs usually have low malignant potential with an indolent clinical course. However, they are well known for their late recurrences even in patients with stage I disease. More than one-third of patients with ESS develop a recurrence which necessitates a long-term follow-up. The most common sites of involvement/ recurrences include the ovary, pelvis, abdomen, and less frequently lung and vagina. Extra-uterine ESS (EESS) is a well-documented entity in the literature; however, it is a rare occurrence as a result of malignant transformation of endometriotic implants [3, 4].

ESS in the urinary bladder is extremely rare with less than 10 cases reported in literature till now to the best of our knowledge [5]. We hereby present a case of urinary bladder ESS with its histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular features compatible with a low-grade ESS (LG-ESS).

Case History

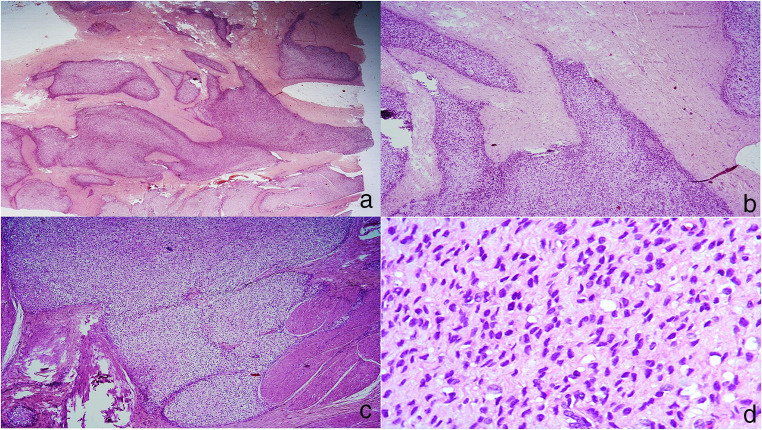

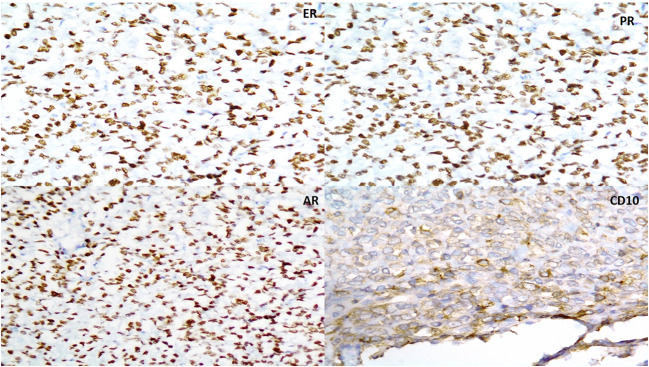

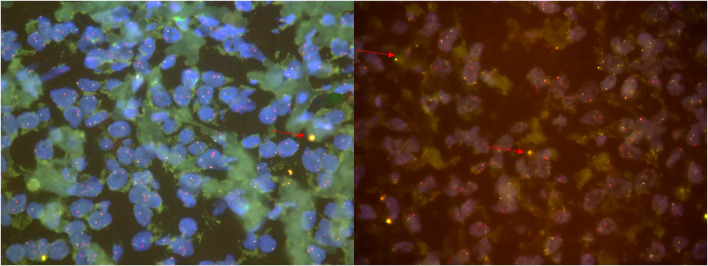

A 45-year-old female with no comorbidities presented with history of hematuria since 2 months. Details of past history of hysterectomy done were not available. On contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT), a 7.5 × 5.5 cm irregularly enhancing mass was seen arising from the left lateral wall of the urinary bladder with a large extra-luminal component extending antero-laterally and abutting the soft tissue of the anterior abdominal wall. There was an associated tumor thrombus in the iliac veins. The left ovary was normal. The right ovary was not seen. Urine cytology was negative for malignancy. Subsequently, a limited transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) was done which revealed a tumor composed of round to ovoid and focal spindle cells arranged in diffuse sheets in a myxoid and hyalinized matrix with minimal pleomorphism. Mitosis was 1–2/10 high-power field (hpf). Necrosis was absent. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor was positive for vimentin and negative for SMA, AE1/AE3 (epithelial marker), p63, S100p, HMB45, desmin, C-kit (CD99), DOG1, and H-caldesmon. A diagnosis of mesenchymal tumor with intermediate nuclear grade was offered. Patient underwent radical cystectomy, and on the resected specimen, a tumor was identified measuring 7.2 × 5.7 cm with permeative tongues of tumor within the wall of the urinary bladder involving the detrusor muscle bundles without any appreciable inflammation or stromal reaction. The cytomorphology was similar to that seen in the TURBT. Focally, perivascular arrangement of the tumor cells was identified. Mitotic activity was 1–2/10 hpf. Necrosis was not seen (Fig. 1a-d). As the morphology suggested and resembled a uterine ESS, additional immunostaining was performed. CD10 was focally positive, and estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and androgen receptor (AR) were strongly and diffusely positive (Fig. 2a-d). On molecular studies utilizing JAZF1 and JJAZ1 fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), more than 50% nuclei showed either loss of green signal or a break apart pattern of JAZF1 and JJAZ1, thus confirming this to be a low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (Fig. 3). The patient received adjuvant radiotherapy at a dose of 50 Gy for 25 cycles. On follow-up positron emission tomography (PET) scan after adjuvant radiotherapy, no metabolically active disease was noted anywhere in the body.

Fig 1.

a–d Cellular tumor showing permeative edges and composed of round to ovoid and focal spindle cells arranged in diffuse sheets in a myxoid and hyalinized matrix with minimal pleomorphism (H&E)

Fig 2.

a–d Immunohistochemistry results showing positivity for estrogen receptors (ER-2a), progesterone receptor (PR-2b), androgen receptor (AR-2c), and CD10 (2d)

Fig. 3.

FISH break apart assay for detection of translocation involving the JAZF1 gene showing fused signals

Discussion

Secondary neoplasms of the bladder are rare and can occur as a direct extension of tumor from the adjacent organs like the colon, prostate, ureter, and uterus or through metastasis. Bates and Baithun had studied 282 secondary bladder neoplasms, of which majority were metastatic carcinomas from the colon, prostate, rectum, cervix, etc. Noncarcinomatous tumors were extremely rare and included melanoma, Ewing sarcoma/PNET, mesothelioma, and osteosarcoma [5, 6]. No case of EESS involving the bladder was identified in their study.

The largest study on EESS published by Masand et al. had 63 cases of EESS. The common complaints at presentation were abdominal/pelvic mass, vaginal bleeding, and gastrointestinal symptoms. The most common sites involved for EESS were the ovaries, rectal wall, peritoneum, and vagina. The urinary bladder as a site of involvement is extremely rare with very few cases reported in literature till now. Approximately 25% of their cases had an initial diagnosis other than ESS which included sex cord stromal tumor, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, and leiomyosarcoma [7]. Our patient was also initially reported as having intermediate-grade sarcoma on TURBT specimen.

Masand et al. reported associated endometriosis in approximately 60% of their ESSs. In cases where endometriosis was not identified, it is possible that they originated from gland-poor endometriosis; i.e., stromal endometriosis or the overgrowth of tumor obscured the underlying endometriosis or it may arise de novo from the coelomic or subcoelomic multipotential epithelium. History of endometriosis was not available in our case at the time of diagnosis; however, there was a past history of hysterectomy done for unknown/uncertain cause. At its usual location, the typical symptoms include abdominal/pelvic mass and pain, abnormal vaginal bleeding, gastrointestinal symptoms, such as vomiting, constipation, bleeding, and small-bowel obstruction, and urinary symptoms, such as hematuria, urgency, frequency, and incontinence. However, unusual locations cause a diagnostic challenge due to site-specific varied symptoms [7, 8].

EESS of the bladder is very rare with only 3 single case reports published. Epstein et al. published the largest series of 6 cases of EESS involving the bladder. Five of their patients had recurrences in the bladder ranging from 7 to 30 years (mean 18 years) after the initial diagnosis of ESS or hysterectomy. Two of them had a previous diagnosis of ESS whereas in 3 cases, hysterectomy was performed for uncertain or benign causes. Four of their patients presented with tumor masses, one presented with an abdominal pain, and only one case presented with hematuria which is seen in our case also [5] Table 1

Table 1.

Clinical information about cases in the literature

| Hys diagnosis | Tx at Hys | Age at bladder rec | Clinical findings | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epstein et. al (6 cases) | |||||

| 1 | ESS | TAHBSO | 49 | Pelvic mass by imaging | Surgery |

| 2 | Unknown | Hys | 72 | Nocturia, hematuria | Partial cystectomy |

| 3 | Benign | Hys | 77 | Intermittent lower abdominal pain | TURB, partially removed |

| 4 | Unknown | Hys | 69 | Recurrent neoplasm of the bladder, lung metastasis | TURB and chemo for the bladder |

| 5 | ESS | Hys, pelvic radiation | 50 | Bladder tumor | TURB and chemotherapy |

| 6 | ESS | 2 surgeries TAHBSO, R hemicolectomy, partial cystectomy | 44 | Abdominal mass | Arimidex |

| Masand et al. | – | – | 36 | Urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence | Surgery |

| Dgani et al. | LG-ESS | Hys | 41 | Hematuria | Surgery |

| Current case | Unknown | Hys | 45 | Hematuria | TURB followed by radical cystectomy + adjuvant radiotherapy |

Hys hysterectomy, Tx treatment, TAHBSO total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, LN lymph node, rec recurrence, TURB transurethral resection of the bladder, R right

ESS of the bladder or ESS involving the bladder at initial presentation with an associated obvious gynecologic primary tumor or as a late recurrence involving other pelvic organs generally does not cause a diagnostic challenge. However, when ESS occurs as late recurrences with urinary tract symptoms as the only presentation, it can cause a significant diagnostic dilemma for pathologists, especially when the primary tumor diagnosis is not readily available [5–7].

Morphologically, LGESS has a distinct tongue-like permeative pattern of invasion into the deeper layers (myometrium or detrusor as in this case) which was seen in our case. Lymphatic invasion is also characteristically seen. However, this pattern of invasion may be lacking at extra-uterine sites, where the tumor typically has a multinodular appearance. A variety of stromal patterns/stromal changes have been described in LG-EESS such as fibroma-like variant (> 50% of the cases), prominent hyaline plaques, foam cell change, and myxoid change. Less common patterns include a pseudo-papillary pattern, angiomatous pattern, epithelioid cell change, and clear change [8]. In contrast, the high-grade ESS or an undifferentiated sarcoma will exhibit stromal invasion, hemorrhage and necrosis, marked nuclear pleomorphism, and high mitotic activity. Also, in the absence of history of endometriosis, at extra-uterine sites, they can be misdiagnosed as cellular leiomyoma, low/high-grade leiomyosarcoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor [9].

Immunohistochemical findings in the paper by Epstein et al. revealed diffuse and strong positivity for CD10, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) in all the six cases. CD56 and desmin were positive in 4 out of 6 cases with either diffuse or patchy staining. Two cases were positive for synaptophysin (diffuse) and p16 each (patchy) [4]. The present case also showed diffuse and strong positivity for ER and PR and patchy positivity for CD10. We additionally had diffuse and strong positivity for androgen receptor (AR) which was not performed in their study.

Genetic studies can provide additional diagnostic insights, as low-grade ESSs frequently harbor fusions involving JAZF1/SUZ12 and/or JAZF1/PHF1, whereas high-grade ESSs are defined by YWHAE–NUTM2A/B fusions. Various chromosomal translocations have been reported in ESS indicating morphological as well as cytogenetic heterogeneity. A subgroup of endometrial stromal tumors is characterized by the presence of a specific gene fusion in which two zinc finger genes (JAZF1 and JJAZ1) are fused as a result of t(7;17) (p15;q21) translocation. It is not necessary to use molecular techniques for the diagnosis of otherwise low-grade ESS. However, they can be used in cases with unusual histomorphology where ESS is at a differential or extra-uterine site (like our case) or is metastasizing [10, 11].

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hendrickson MR, Tavassoli FA, Kempson RL, McCluggage WG, Haller U, Kubik-Huch RA. Mesenchymal tumours and related lesions. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boll D, Verhoeven RH, van der Aa MA, Pauwels P, Karim-Kos HE, Coebergh JW, et al. Incidence and survival trends of uncommon corpus uteri malignancies in the Netherlands, 1989-2008. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:599–606. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318244cedc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clair K, Wolford J, Veran-Taguibao S, Kim G, Eskander RN. Primary low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma of the omentum. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;21:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Back JA, Choi MG, Ju UC, Kang WD, Kim SM. A case of advanced-stage endometrial stromal sarcoma of the ovary arising from endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016;59(4):323–327. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2016.59.4.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian W, Latour M, Epstein JI. Endometrial stromal sarcoma involving the urinary bladder: a study of 6 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(7):982–989. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates AW, Baithun S. Secondary neoplasms of the bladder are histological mimics of nontransitional cell primary tumours: clinicopathological and histological features of 282 cases. Histopathology. 2000;36:32–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masand RP, Euscher ED, Deavers MT, Malpica A. Endometrioid stromal sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(11):1635–1647. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masand RP. Unusual presentations of gynecologic tumors: primary, extrauterine, low-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(4):536–541. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0241-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alessandrini L, Sopracordevole F, Bertola G, Scalone S, Urbani M, Miolo G, Perin T, Italia F, Canzonieri V. Primary extragenital endometrial stromal sarcoma of the lung: first reported case and review of literature. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13000-017-0627-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hrzenjak A, Moinfar F, Tavassoli FA, Strohmeier B, Kremser ML, Zatloukal K, Denk H. JAZF1/JJAZ1 gene fusion in endometrial stromal sarcomas: molecular analysis by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction optimized for paraffin-embedded tissue. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7(3):388–395. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60568-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Anand M, Haimes JD, Manoj N, Berlin AM, Kudlow BA, Nucci MR, Ng TL, Stewart CJ, Lee CH. The application of next-generation sequencing-based molecular diagnostics in endometrial stromal sarcoma. Histopathology. 2016;69(4):551–559. doi: 10.1111/his.12966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]