Abstract

Objectives: Care for older adults with cancer became more challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic. We sought to examine cancer care providers' attitudes toward the barriers and facilitators related to the care for these patients during the pandemic.

Materials and Methods: Members of the Advocacy Committee of the Cancer and Aging Research Group, along with the Association of Community Cancer Centers, developed the survey distributed to multidisciplinary healthcare providers responsible for the direct care of patients with cancer. Participants were recruited by email sent through four professional organizations' listservs, email blasts, and messages through social media.

Results: Complete data was available from 274 respondents. Only 15.4% had access to written guidelines that specifically address the management of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Age was ranked fifth as the reason for postponing treatment following comorbid conditions, cancer stage, frailty, and performance status. Barriers to the transition to telehealth were found at the patient-, healthcare worker-, and institutional-levels. Providers reported increased barriers in accessing basic needs among older adults with cancer. Most respondents agreed (86.3%) that decision making about Do Not Resuscitate orders should be the result of discussion with the patient and the healthcare proxy in all situations. The top five concerns reported were related to patient safety, treatment delays, healthcare worker mental health and burnout, and personal safety for family and self.

Conclusion: These findings demand resources and support allocation for older adults with cancer and healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Older adults, Geriatric oncology, COVID-19, Health care providers

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, the world has been confronting 2019 Novel Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), categorized as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, when over 118,000 cases were diagnosed across the globe [1]. As of May 1, 2020, the day this study's data collection ended, the number of confirmed cases had increased to 3,127,126 with 233,388 deaths [2]. COVID-19 has an exceptionally large impact on older adults (age ≥ 65) [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7]], people with multiple comorbidities [[3], [4], [5],8,9], and those with cancer [7,[10], [11], [12], [13]]. The management of older adults with cancer across the disease trajectory has significant challenges (i.e., comorbidity, frailty, polypharmacy) to which COVID-19 is now added [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. Recent research has found that older adults with cancer present with increased symptom severity and are more likely to die than younger adults when diagnosed with COVID-19 [6,11,17].

Providing excellent oncologic care to older adults with cancer is challenging primarily due to the lack of evidence-based treatment options [[18], [19], [20]], or guidelines for treating specific cancers in older adults [[21], [22], [23]]. This challenge has been intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, and there has been a call for cancer-specific COVID-19 guideline development and uniform implementation [24,25]. The delay and cancellation of elective treatments, strict policies limiting visiting for in-patients, and transfer of follow-up care to telehealth rather than in-person visits have all led to concerns on the part of patients and providers [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Health care providers have had to acknowledge crucial unknowns of how these changes may affect the clinical outcomes of older adults with cancer [26].

Our aim was to learn about the experiences, including innovative practices, concerns, and care-delivery barriers, which oncology healthcare providers, both medical decision-makers and psychosocial care providers, are experiencing and/or are observing among older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 crisis. The specific objectives were to learn, in the context of COVID-19, about: 1) the provision of and concerns about cancer care for older adults; 2) decision making regarding cancer treatment and Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders; and 3) barriers and facilitators related to the care of older adults with cancer, particularly regarding telehealth.

2. Materials and Methods

Members of the Advocacy Committee of the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG), along with the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC), developed a Qualtrics survey for multidisciplinary team members responsible for the direct care of people with cancer. For this article, 17 of the 20 survey items regarding the care for older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic are addressed. The three additional questions are qualitative, and that manuscript is currently under peer review. Six questions on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) were scenarios focused on Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders among older adults with cancer and COVID-19. One question regarded potential age cutoffs for automatic DNR orders. Five questions focused on the factors associated with the prioritization or rescheduling of cancer treatments, receipt of guidance for decision-making, and the existence or lack of written guidelines regarding the management of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other questions addressed barriers associated with the use of telehealth and increased barriers observed among older people with cancer. Information about participants' professional history was also collected (Appendix 1).

The three inclusion criteria were 1) providing care for people with cancer, 2) participating in the study voluntarily, and 3) understanding that the results may be reported in multiple publications. Participants were recruited by email sent through four cancer focused professional organizations' listservs and email blasts (ACCC, CARG, Association of Oncology Social Work, and Social Work Hospice & Palliative Care Network) as well as social media messages (e.g., Twitter, Facebook), with a request to forward the survey to other cancer care professionals. Each organization had a unique survey link to enable quantifying responses by group. We were interested in the experiences of all cancer care providers, including medical and psychosocial, to ensure a full picture of the care of older adults with cancer. The survey was available from April 8, 2020 until May 1, 2020. The median time to complete was 11 min. The study was determined not to be human research by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board as no identifying information was included in the data used for analysis. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages). All quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS 23.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Four hundred ninety-five potential respondents started the survey; 274 (55.4%) met the required inclusion criteria and completed the survey. Most respondents were either social workers (43%) or medical doctors/advanced practice providers (28.3%) (Table 1 ). The majority (68.5%) reported that more than half of their patients are over the age of 65. The length of professional experience (post-training years) the respondents have provided care to people with cancer was fairly evenly distributed between one to more than 20 years (ranged from a low of 1 to 4 years (20.5%) to a high of 11 to 20 years (28.9%). The vast majority (92%) of respondents were based in the U.S., and the majority were practicing in urban areas (53.1%). Over 36% reported working in an academic/National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, while 29% practiced in a community cancer program (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information of survey respondents (n = 274).

| Variable | % |

|---|---|

| Profession | |

| Medical Doctor and Advanced Practice Providers a | 28.3 |

| Social Worker | 43.0 |

| Administrator/Program Leader | 8.1 |

| Navigator | 5.1 |

| Multiple | 6.3 |

| Other b | 9.2 |

| Percentage of patients with cancer older than age 65 | |

| <10% | 0.7 |

| 10–25% | 4.4 |

| 25–50% | 26.4 |

| 50–75% | 57.1 |

| >75% | 11.4 |

| Years providing care to patients with cancer | |

| 1–4 | 20.5 |

| 5–10 | 24.2 |

| 11–20 | 28.9 |

| 20+ | 26.4 |

| Country of care – USA | 92.0 |

| Classification of cancer program | |

| Academic/NCI comprehensive cancer center | 36.4 |

| Community cancer program | 29.0 |

| Hospital | 17.3 |

| Integrated network cancer program | 7.0 |

| Physician-owned oncology practice | 4.0 |

| Physician practice | 0.4 |

| Other | 5.9 |

| Location of cancer program/institution | |

| Urban/city | 53.1 |

| Suburban | 29.5 |

| Rural | 17.3 |

Oncologists, geriatricians, or advanced practice providers. Oncologists included medical, surgical, radiation, gynecologic, and geriatric specialties.

Includes oncology nurses (12), dieticians (3), pharmacists (2), case managers (2), medical assistants (2), pulmonologist (1), radiation therapist (1), and a research nurse (1).

3.2. Decision-Making

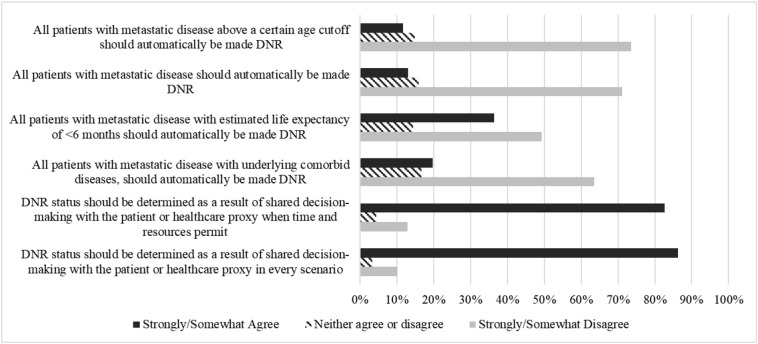

Participants were asked to identify their level of agreement with six scenarios regarding DNR orders for people with cancer who are COVID-19 positive. Most respondents strongly or somewhat disagreed that all patients with metastatic disease above a certain age should automatically be made DNR (73.6%) or that all patients with metastatic disease should automatically be made DNR order (73.6%). A large majority of respondents (82.7%) strongly or somewhat agreed that the decision regarding a DNR order should be the result of shared decision-making with the patient and/or the healthcare proxy when time and resources permit, with more supporting a shared-decision making conversation in every scenario (86.3%) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Scenarios for automatic DNR.

Only 15.4% of respondents reported they had access to written guidelines that specifically address the management of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 crisis. In comparison, 54.9% said that there were no written guidelines provided to them, and 29.7% were unsure if such guidelines were available.

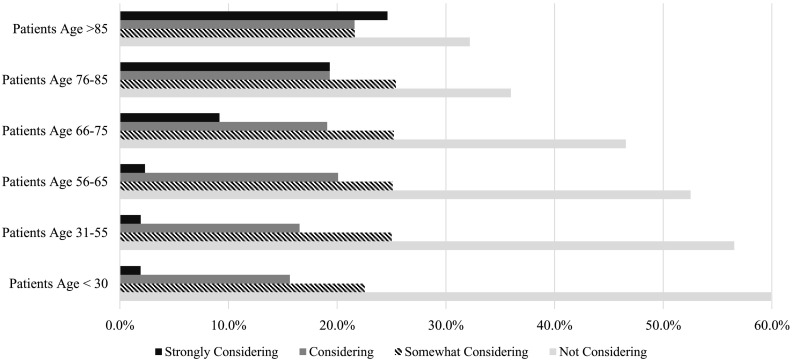

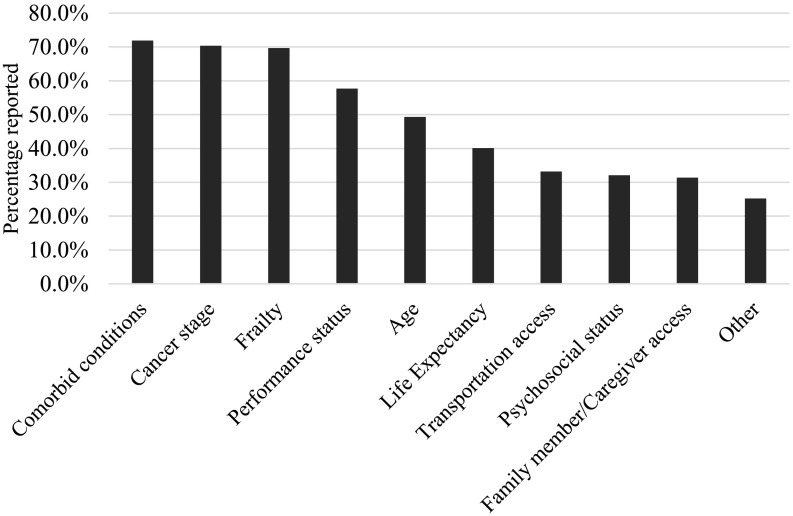

Participants were asked to indicate how strongly they were considering postponing or rescheduling treatments by age group. While 17.5% of respondents were strongly considering/considering postponing or rescheduling treatment for younger patients (age 30 and below), 46.2% were strongly considering/considering postponing or rescheduling treatment for patients aged >85. (Fig. 2 ). The top five reasons considered for postponement or rescheduling cancer treatment were comorbid conditions (71.9%), cancer stage (70.4%), frailty (69.7%), performance status (57.7%), and age (49.3%) (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 2.

Considering postponing or rescheduling treatment by patient age group.

Fig. 3.

Considerations in making decisions about postponing or rescheduling treatment during pandemics.

The most common sources for support or guidance for decision making during the COVID-19 pandemic were other oncologists (60.6%), medical directors (55.5%), and health system/institutional administration (54.4%) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Providing support and guidance.

| Source of support and guidance | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Other oncologists | 166 | 60.6 |

| Medical Director | 152 | 55.5 |

| Health System/Institutional Administration | 149 | 54.4 |

| Department/Division Chair | 132 | 48.2 |

| Other oncology health care providers | 100 | 36.5 |

| Ethics Committee | 37 | 13.5 |

| Other a | 30 | 10.9 |

Includes national organizations such as ACOG, ACRO, ASCO, ASTRO, COA, NCCN.

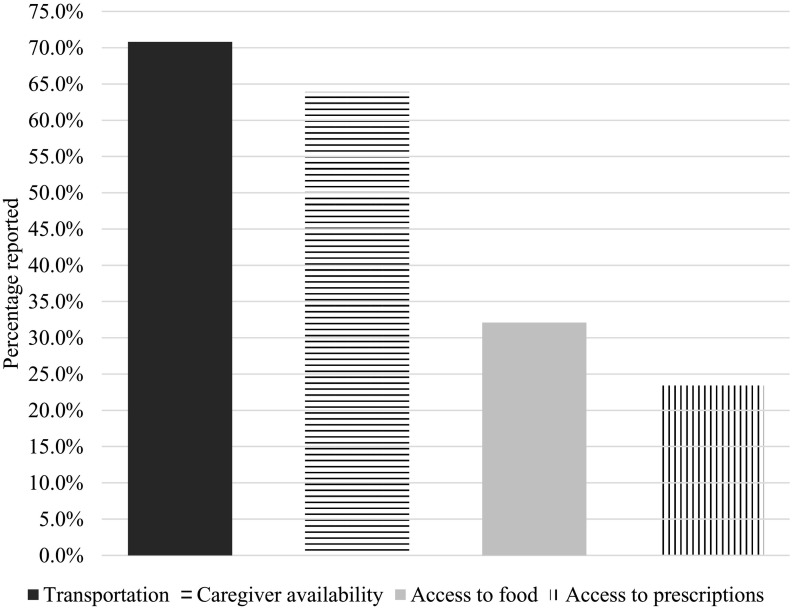

When asked to select from four barriers one or more for which they had seen an increase for older adult patients since the pandemic began, respondents most often cited transportation (70.8%), followed by caregiver availability (63.9%), access to food (32.1%), and access to prescriptions (23.4%). (Fig. 4 )

Fig. 4.

Barriers increased among older adults with cancer.

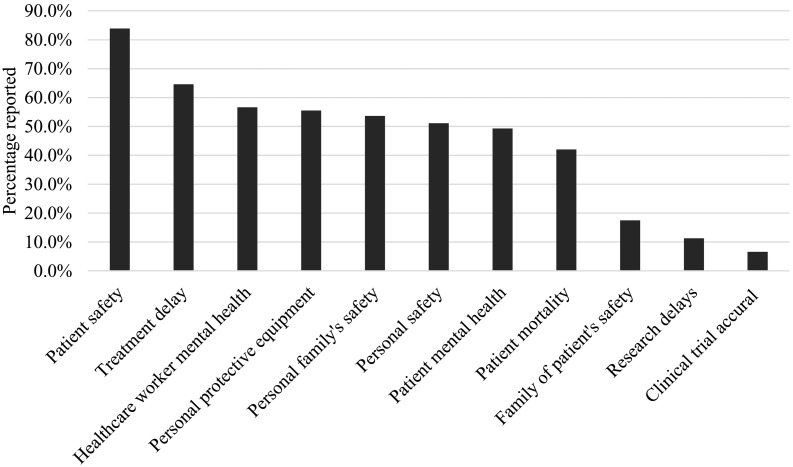

When participants were asked to rank their top five concerns out of eleven options, patient safety was in the top five the most often (83.9%) followed by treatment delays (64.6%), healthcare worker mental health and burnout (56.6%), personal protective equipment safety (55.5%), respondent's family safety (53.6%), personal safety (51.1%), and patient mental health (49.3%) (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Top ranked concerns for older adults with cancer.

3.3. Barriers to the Use of Telehealth

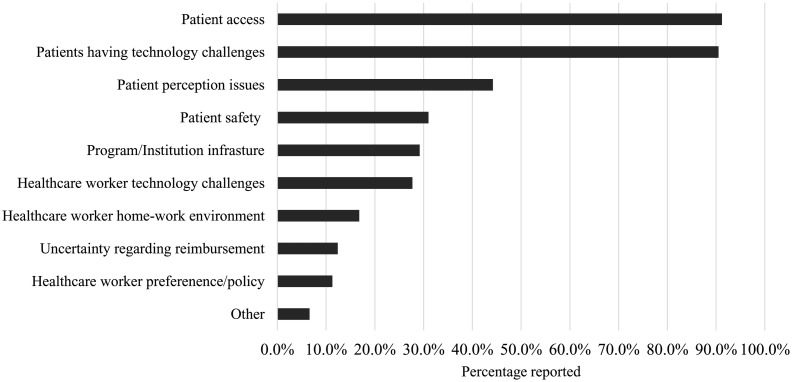

The two most common reported barriers to the use of telehealth were patient access [e.g., no smartphones or high-speed internet (91.2%) and patients having technology challenges (90.5%)]. Additionally, 44.2% reported the patient's perception of using telehealth, such as older adults having a strong preference for face-to-face care. The final patient-related barrier was a concern for patient safety, where the prescribed treatment regimen is not appropriate for telehealth (31%). Other barriers included infrastructure issues within the institution or program (29.2%), healthcare workers having technology challenges (27.7%), and issues with the healthcare workers' home-work environment (16.8%). Last was uncertainty regarding reimbursement (12.4%) and healthcare worker preferences (11.3%) (See Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Barriers to using telehealth with older adults with cancer.

Other patient conditions identified as causing barriers to telehealth utilization included being hard of hearing, having impaired cognitive status, being hospitalized or in a nursing home, and difficulty in having a caregiver or family member present for the visit. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) security issues were mentioned, as was the inability to connect with a patient virtually the same as in a face-to-face appointment. Final comments focused on the difficulty older adults may have in adapting to the change to telehealth.

4. Discussion

Medical care, as we know it, has been transformed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The impact on vulnerable patient populations, such as older adults with cancer, has been notable. In this study, the research team sought to identify barriers and facilitators to care for older adults with cancer during the first few months of this pandemic with the goal of improved support for patients and providers moving forward.

Most survey respondents did not agree with any automatic DNR status policies and strongly believed that DNR status should be a shared decision with patients in every scenario. Given the current resource-limited climate, coupled with visitor restrictions, shared decisions about DNR status at the bedside may be more challenging than before. As a result, it is crucial to have DNR and other advanced care planning discussions and documentation prior to urgent medical needs [27]. Despite modified palliative response plans and faced with limited resources, decisions, and rationale regarding DNR must be communicated clearly and in a timely fashion with the patient, if possible, and with the family [28]. It is imperative that care teams work together to deliver ethical palliative and end of life care in light of the current obstacles being faced during the COVID19 pandemic [29].

Respondents' degree of consideration for postponing or rescheduling treatment increased as age increased. These responses could be due to insufficient data related to toxicity versus the benefit of cancer treatments in older adults, even in the clinical trial setting [18]. This could also be due to a more restrictive approach, i.e., excluding older adults from treatment during the COVID-19 crisis as in the French authorities' guidelines [[30], [31], [32]]. Unfortunately, these may be related to an ageist approach that older adults with cancer should not receive equal treatment [17,33,34]. One other possibility is the notion that older adults are more likely to have comorbid conditions or be frail and, hence, at higher risk for cancer treatment toxicity during the COVID-19 crisis. When respondents were asked to list factors associated with their decision making, comorbid conditions, frailty, and performance status were among the top four concerns. This result corresponds with the burgeoning evidence that suggests that older age and higher comorbidity are associated with more severe COVID-19 symptoms and negative outcomes [11,14,25,26,35,36].

In this study, age was the fifth most common factor considered in the postponement and rescheduling of cancer treatment. This may be because over 68% of the study sample regularly provided care for older adults with cancer and the likelihood that they were trained to acknowledge the heterogeneity of older adults and consider elements of geriatric assessments (frailty, performance status) as well as cancer stage in their care [37]. It is also important to note that respondents to our survey were members of various groups, one being the Cancer and Aging Research Group, who may have more exposure to concepts of frailty in older adults with cancer. Researchers have shown the disparities in cancer care and survival related to age as well as other factors such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status [[38], [39], [40], [41], [42]]. Future research should examine how these factors inform how institutions, providers, and older patients should consider postponing and rescheduling cancer treatments during the current pandemic as well as future COVID-19 waves and future health crises in general, especially when there is lack of expertise in the care for older adults with cancer. Such studies are crucial. Only 15% of our respondents were aware of institutionally or nationally written guidelines on how to care for older adults with cancer during COVID-19. Instead, they had to rely on their peers, medical directors, and institutional administration for guidance.

This unprecedented situation can put caregivers in a challenging position regarding the balance between treating patients appropriately (i.e., not undertreating) and maintaining safety for patients who are in a high-risk group. This has been made analogous to the classic Scylla and Charybdis by Dr. Mark Lewis [43] and is an apt analogy; how do we navigate this journey with our patients amidst competing risks? CARG has published a perspective piece with guidelines on how to best approach older patients based on functional status and goals of care conversations. Treatment approaches will necessarily be based on best practices at individual centers and shared decision making between patients/caregivers and the treatment team [44].

4.1. Barriers for Older Adults

Healthcare providers believe that older adults with cancer are experiencing significant increases in barriers such as transportation, caregiver availability, and access to food and prescriptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Withdrawal of the formal and informal functional supports on which many vulnerable older adults rely can negatively impact their current cancer prognosis as well as physical and mental health. The stress associated with getting basic and clinical needs fulfilled while attempting to be safe as a member of an at-risk population is daunting. It is essential to be mindful of the challenge that physical distancing is creating for vulnerable older adults and to address these challenges head-on [16]. One way of addressing the needs of older adults, in particular those with cancer, has been through technology. However, as evidenced by this study and others [[44], [45], [46]], there are major barriers (e.g., sensory impairments, access, financial, infrastructure) to technology and telemedicine. Clinicians should be aware of these difficulties and consider simple, common-sense interventions that are beneficial to both parties, appropriately based on medical need and avoiding unnecessary exposure to the virus, while continuing therapeutic relationships and cancer management [45].

One option to consider when evaluating patient appropriateness for an in-person visit is to transition from intravenous chemotherapy to oral chemotherapy. While this survey did not address providers' preferences as such, several societies have advocated for this change when possible [47]. Important factors to remember in the older patient population are: adherence to medication, increasing risk of medication interactions with polypharmacy, and changes in bioavailability in the older patient [48]. Again, this discussion must be based on shared decision making and risk/benefit analysis.

5. Limitations

The first limitation was that several of the survey items asked explicitly about older adults. Therefore, even those respondents who did not primarily care for older adults were asked to think specifically about this age group. This limitation may skew the findings to the experiences related to older adults with cancer, away from experiences related to the overall population of people with cancer. A second limitation is the uneven distribution of healthcare providers. The largest professional group to respond was oncology social workers, followed by MDs and APPs. This potentially alters the findings to a psychosocial lens rather than a lens of those who make the decisions about treatments. The third limitation is that most of the respondents work in urban areas, again, possibly skewing the findings to the urban experience and away from suburban and rural settings. Finally, the respondents self-selected to complete the survey, so the findings are not generalizable beyond this sample.

6. Conclusion

This study examined the experiences, including innovative practices, concerns, and barriers that oncology healthcare providers are having and/or observing among older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 crisis. Results indicated that providers received little written guidance regarding caring for older adults with cancer. Providers also felt strongly against automatic DNR and that it should always be a shared decision. Comorbidity was the leading factor when considering rescheduling/postponing treatment. More research is needed to understand the impact COVID-19 has on the care delivery to older adults with cancer. In addition, these results demand resource and support allocation not only for older adults with cancer but also for healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology: KB, JLKS, ARM, BC, EP, LMB, AS. Data curation: KB, EP, LMB, AK. Formal analysis: KB, JLKS, JLP, ARM, EP, AS. Project admiistration: KB, EP. Resources, Software: EP, LMB. Validation: KB, EP. Visualization: JLP. Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing: KB, JLKS, JLP, ARM, BC, EP, LMB, AK. Approval of Final Article: KB, JLKS, JLP, ARM, BC, EP, LMB, AK. Funding acquisition, INvestigation, Supervision: n/a

Declaration of Competing Interest

KB: Consultant for Blue Note Therapeutics, Inc.

All other authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest.

Acknowledgments

The societies and groups (ACCC, CARG, Association of Oncology Social Work, and Social Work Hospice and Palliative Care Network) who helped distribute the survey to their members. This project was supported in part by the grant No. P30 CA008748 from the National Institute of Health, United states.

Appendix 1: Study Survey Items

Care for Older Adults with Cancer during COVID-19 Pandemic

Please mark each box below, as appropriate, to signify that you meet the following participation criteria:

□ I provide care for patients with cancer.

□ I am participating in this survey of my own choice.

□ I understand that the summarized data results may be used for one or more manuscripts that will be submitted for publication.

Q1 In what country do you provide cancer care?

○ USA

○ Other (please specify) ________________________________________________

Q2 Approximately what percentage of your patients with cancer are older than age 65?

○ < 10%

○ 11–25%

○ 26–50%

○ 51–75%

○ >75%

Q3 Please drag and drop the items below to rank your top 5 concerns related to COVID-19. (In order- your top concern should be #1.)

| Top 5 Concerns Related to COVID-19 |

| Personal Protective Equipment Supply |

| Personal Safety |

| Family of Patient's Safety |

| Your Family's Safety |

| Patient Safety |

| Patient Mental Health |

| Healthcare Worker Mental Health or Burnout |

| Treatment Delays |

| Patient Mortality Rate Increasing |

| Clinical Trial Accrual |

| Research Delays or Disruptions |

Q4 With regard to your provision of care during the COVID-19 pandemic, which group of patients with cancer are you inclined to prioritize treatment for?

○ Younger patients more than older patients

○ Older patients more than younger patients

○ Both groups are equally prioritized

Q5 Indicate which patients you intend to postpone or reschedule treatment for due to COVID related concerns:

| Not considering | Somewhat considering | Considering | Strongly Considering | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients Age < 30 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Patients Age 31–55 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Patients Age 56–65 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Patients Age 66–75 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Patients Age 76–85 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Patients Age > 85 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Q6 When considering whether to postpone/reschedule cancer treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic, do you take into account: (select all that apply)

□ Age

□ Cancer stage

□ Comorbid conditions

□ Frailty

□ Life expectancy

□ Performance status

□ Psychosocial status

□ Employment status

□ Insurance status

□ Family member/caregiver access

□ Transportation access

□ Other: ________________________________________________

Q7 Within your program, who/which entity is providing support or guidance in decision-making regarding treating patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic? (Select all that apply.)

□ Health System/Institution Administration

□ Medical Director

□ Department/Division Chai

□ Ethics Committee

□ Other hematologists and/or medical oncologists

□ Other oncology health care providers

□ Pharma/drug companies

□ No guidance has been provided

□ Other ________________________________________________

Q8 Does your program have specific written guidelines regarding the management of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 crisis?

○ Yes

○ No

○ Not sure

Q9 When it comes to Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders in the setting of a cancer diagnosis and a positive COVID-19 diagnosis with symptoms (e.g. cough, fever, shortness of breath), regardless of your responsibility for making such decisions, please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

| Strongly agree | Somewhat agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Somewhat disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients with metastatic disease should automatically be made DNR. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| All patients with metastatic disease with estimated life expectancy of < 6 months should automatically be made DNR. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| All patients with metastatic disease above a certain age cutoff should automatically be made DNR. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| All patients with metastatic disease, with other underlying comorbid diseases, should automatically be made DNR. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| DNR status should be determined as a result of shared decision-making with the patient or healthcare proxy when time and resources permit. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| DNR status should be determined as a result of shared decision making with the patient or healthcare proxy in every scenario. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Q10 In the case of an overwhelmed health care system, what is the age cutoff where automatic DNR should occur?

○ 55

○ 65

○ 75

○ 85

○ It should not occur

○ Not sure

○ Other ________________________________________________

Q11 Due to COVID-19, health care providers have rapidly expanded the use of telehealth. Please select which of the following are barriers to using telehealth with your older adult patients (age 65+) during this time: (select all that apply)

□ Program/institution's infrastructure

□ Healthcare worker home-work environment/infrastructure

□ Uncertainty regarding reimbursement

□ Patient access (e.g., no smart phone or high-speed internet access)

□ Patient is not tech-savvy

□ Patient perception issues (e.g., strong preference for face-to-face care)

□ Healthcare worker technology challenges

□ Healthcare worker preference/policy

□ Patient safety (treatment regimen not appropriate for telehealth)

□ No barriers to telehealth

□ Other________________________________________________

Q12 Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I have seen increased barriers for my older adult patients as it relates to: (select all that apply)

□ Access to food

□ Caregiver availability

□ Access to prescriptions

□ Transportation

□ None of the above

DEMOGRAPHICS

Q13 How many years have you have been providing care to patients with cancer (not including your “training years”)?

○ 1 to 4 years

○ 5 to 10 years

○ 11 to 20 years

○ Over 20 years

Q14 Indicate your profession/specialties: (select all that apply)

□ Medical Oncologist/Hematologist

□ Surgeon/Surgical Oncologist

□ Internist/Hospitalist

□ Geriatrician

□ Palliative Care

□ Gynecologic Oncologist

□ Radiation Oncologist

□ Advanced Practice Provider (NP, CNS, PA)

□ Oncology Nurse

□ Oncology Nurse Navigator

□ Social Worker

□ Patient Navigator (not Nurse or Social Worker)

□ Psychologist

□ Financial Counselor

□ Pharmacist

□ Administrator/Program Leadership

□ Other (please specify)________________________________________________

Q15 Indicate the classification of your cancer program: (select one)

○ Academic/NCI Comprehensive Cancer Program

○ Community Cancer Program

○ Hospital

○ Integrated Network Cancer Program

○ Physician-owned oncology practice

○ Physician practice (other)

○ Other (please specify) ________________________________________________

Q16 In what type of setting is your cancer program/institution located?

○ Urban/City

○ Suburban

○ Rural

Q17 Please list up to 5 clinical barriers caused by COVID-19 as they relate to caring for older adults with cancer.

Q18 What are the top 3 questions regarding COVID-19 being asked of you/your colleagues by older adult patients with cancer?

Q19 Is there anything else you would like to share with us about your experience as a member of the cancer care team during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Q20 Please provide your contact information (all responses will be de-identified before sharing more broadly). This is optional; however, we appreciate your response so that we may better understand who participated in this survey.

○ First Name________________________________________________

○ Last Name ________________________________________________

○ Credentials (e.g., MD, RN, PharmD, MSW, NP, PA) _______________________

○ Role/Title ________________________________________________

○ Email Address ________________________________________________

○ Cancer Program/Institution Name (no abbreviations) _________________________

○ Cancer Program City, State (if USA)_________________________________

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020 Mar. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johns Hopkins University . 2020. Coronavirus COVID-19 global cases by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain V., Yuan J.M. 2020 Jan 1. Systematic review and meta-analysis of predictive symptoms and comorbidities for severe COVID-19 infection media. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murthy S., Gomersall C.D., Fowler R.A. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Mar 11;323:1499–1500. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020 Mar 23;323(18):1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu K., Chen Y., Lin R., Han K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect. 2020 Mar 27:e14–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H., Zhang L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Apr 1;21(4):e181. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arentz M., Yim E., Klaff L., Lokhandwala S., Riedo F.X., Chong M. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA. 2020 Mar 19;323(16):1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang T., Du Z., Zhu F., Cao Z., An Y., Gao Y. Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020 Mar 21;395(10228):e52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30558-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu J., Ouyang W., Chua M.L., Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Mar 25;6(7):1108–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., Wang W., Li J., Xu K. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar 1;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., Wang Y., Chen Y., Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020 Mar 5;92:568–576. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pothuri B., Secord A.A., Armstrong D., Chan J., Huh W., Kesterson J. Anti-cancer therapy and clinical trial considerations for gynecologic oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. J Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.04.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutikov A., Weinberg D.S., Edelman M.J., Horwitz E.M., Uzzo R.G., Fisher R.I. A war on two fronts: cancer care in the time of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 27;172(11):756–758. doi: 10.7326/M20-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bersanelli M. Controversies about COVID-19 and anticancer treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Immunotherapy. 2020;12(5):269–273. doi: 10.2217/imt-2020-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alipour S. Covid-19 and cancer patients: delving into burning questions. Arch Breast Cancer. 2020 Feb 29:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falandry C., Filteau C., Ravot C., Le Saux O. Challenges with the management of older patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatric Oncol. 2020 Apr 2;11:747–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BrintzenhofeSzoc K., Daratsos L. Springer; Cham: 2019. End-of-life care in caring for patients with mesothelioma: principles and guidelines; pp. 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurria A., Levit L.A., Dale W., Mohile S.G., Muss H.B., Fehrenbacher L. Improving the evidence base for treating older adults with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology statement. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov 10;33(32):3826–3833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scher K.S., Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Jun 10;30(17):2036–2038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie A.R., Barsevick A.M., Myers R., Hegarty S.E., Keith S.W., Patel S. Treatment plan consistency with guidelines for older adults with cancer. J Geriatric Oncol. 2019 Sep 1;10(5):832–834. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hale P., Hahn A.W., Rathi N., Pal S.K., Haaland B., Agarwal N. Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in older patients: a network meta-analysis. J Geriatric Oncol. 2019 Jan 1;10(1):149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H., Zhang N., Ho V., Ding M., He W., Niu J. Adherence to treatment guidelines and survival for older patients with stage II or III colon cancer in Texas from 2001 through 2011. Cancer. 2018 Feb 15;124(4):679–687. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shankar A., Saini D., Roy S., Mosavi Jarrahi A., Chakraborty A., Bharti S.J. Cancer care delivery challenges amidst coronavirus disease–19 (COVID-19) outbreak: specific precautions for cancer patients and cancer care providers to prevent spread. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020 Mar 1;21(3):569–573. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.3.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie J., Tong Z., Guan X., Du B., Qiu H., Slutsky A.S. Critical care crisis and some recommendations during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 Mar 2:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05979-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cinar P., Kubal T., Freifeld A., Mishra A., Shulman L., Bachman J. Safety at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: how to keep our oncology patients and healthcare workers safe. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020 Apr 15;1(aop):1–6. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis J.R., Kross E.K., Stapleton R.D. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA. 2020 Mar 27;323(18):1771–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hui D., Paiva C.E., Del Fabbro E.G., Steer C., Naberhuis J., van de Wetering M. Prognostication in advanced cancer: update and directions for future research. Support Care Cancer. 2019 Jun 1;27(6):1973–1984. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04727-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fausto J., Hirano L., Lam D., Mehta A., Mills B., Owens D. Creating a palliative care inpatient response plan for COVID19–the UW medicine experience. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 July;60(1):e21–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.You B., Ravaud A., Canivet A., Ganem G., Giraud P., Guimbaud R. The official French guidelines to protect patients with cancer against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar 25;29:619–621. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The French High Council for Public Health (Haut Conseil de la Santé Publique, HCSP) 2020. Provisional statement: Recommendations on prevention and management of Covid-19 in patients at risk of severe forms [Internet]https://www.hcsp.fr/explore.cgi/avisrapportsdomaine?clefr=799 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 32.SFRO. Society of French Radiation Oncology (Société française de radiothérapie oncologique, SFRO) 2020 May11. Epidémie de COVID-19 [Internet]http://www.sfro.fr/index.php/component/users/?view=login&return=aHR0cDovL3d3dy5zZnJvLmZyL2luZGV4LnBocC9kb2N1bWVudHMvY292aWQtMTkvOTMtY292aWQtMTktbm91dmVsbGVzLXJlY29tbWFuZGF0aW9uLXNmcm8tMjAtMDMtMjAyMA&Itemid=103 cited. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fraser S., Lagacé M., Bongué B., Ndeye N., Guyot J., Bechard L. Ageism and COVID-19: what does our society’s response say about us? Age Ageing. 2020 May 6;49(5):692–695. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayalon L., Chasteen A., Diehl M., Levy B., Neupert S.D., Rothermund K. Aging in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020 Apr 16 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa051. gbaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult in-patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar 11;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta V., Goel S., Kabarriti R. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(7):935–941. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DuMontier C., Sedrak M.S., Soo W.K. Arti Hurria and the progress in integrating the geriatric assessment into oncology: young International Society of Geriatric Oncology review paper. J Geriatric Oncol. 2020 Mar 1;11(2):203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du X.L., Liu C.C. Racial/ethnic disparities in socioeconomic status, diagnosis, treatment and survival among medicare-insured men and women with head and neck cancer. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):913–930. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griffiths R., Gleeson M., Knopf K., Danese M. Racial differences in treatment and survival in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) BMC Cancer. 2010 Dec 1;10(1):625. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du X.L., Sun C.C., Milam M.R., Bodurka D.C. S. FangEthnic differences in socioeconomic status, diagnosis, treatment, and survival among older women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(4):660–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M., Burau K.D., Fang S., Wang H. Du XL. Ethnic variations in diagnosis, treatment, socioeconomic status, and survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2008 Dec 1;113(11):3231–3241. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galvin A., Helmer C., Coureau G., Amadeo B., Joly P., Sabathé C. Determinants of cancer treatment and mortality in older cancer patients using a multi-state model: results from a population-based study (the INCAPAC study) Cancer Epidemiol. 2018 Aug 1;55:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis M.A. Between Scylla and Charybdis — oncologic decision making in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 7;382(24):2285–2287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinman M.A., Perry L., Perissinotto C.M. Meeting the care needs of older adults isolated at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Apr 16;180(6):819–820. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 11;382:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohile S., Dumontier C., Mian H., Loh K.P., Williams G.R., Wildes T.M. Perspectives from the Cancer and Aging Research Group: Caring for the vulnerable older patient with cancer and their caregivers during the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. J Geriatric Oncol. 2020;11(5):753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.04.010. Jun 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Shamsi H.O., Alhazzani W., Alhuraiji A., Coomes E.A., Chemaly R.F., Almuhanna M. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25(6):e936. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mislang A.R., Wildes T.M., Kanesvaran R., Baldini C., Holmes H.M., Nightingale G. Adherence to oral cancer therapy in older adults: the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) taskforce recommendations. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017 Jun 1;57:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]