Abstract

Background

The HEALing Communities Study (HCS) is testing whether the Communities that Heal (CTH) intervention can decrease opioid overdose deaths through the implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in highly impacted communities. One of the CTH intervention components is a series of communications campaigns to promote the implementation of EBPs, increase demand for naloxone and medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and decrease stigma toward people with opioid use disorder and the use of EBPs, especially MOUD. This paper describes the approach to developing and executing these campaigns.

Methods

The HCS communication campaigns are developed and implemented through a collaboration between communication experts, research site staff, and community coalitions using a three-stage process. The Prepare phase identifies priority groups to receive campaign messages, develops content for those messages, and identifies a “call to action” that asks people to engage in a specific behavior. In the Plan phase, campaign resources are produced, and community coalitions develop plans to distribute campaign materials. During the Implement stage, these distribution plans guide delivery of content to priority groups. Fidelity measures assess how community coalitions follow their distribution plan as well as barriers and facilitators to implementation. An evaluation of the communication campaigns is planned.

Conclusions

If successful, the Prepare-Plan-Implement process, and the campaign materials, could be adapted and used by other communities to address the opioid crisis. The campaign evaluation will extend the evidence base for how communication campaigns can be developed and implemented through a community-engaged process to effectively address public health crises.

Keywords: Communication, Opioid Use Disorder (OUD), Overdose, Campaign, Stigma, Evidence-based practices, Helping to end addiction long-term, HEALing communities study

1. Background

Research has demonstrated that health communication campaigns can effectively address important global public health issues such as HIV/AIDS prevention and smoking cessation (Allen et al., 2015; Bala et al., 2017; Durkin et al., 2012; Helme et al., 2014; Firestone et al., 2017; Lefebvre, 2013; Noar et al., 2009; Olawepo et al., 2019; Snyder, 2007; Wakefield et al., 2010). Based on the evolving evidence, health communication campaigns have shifted from general information dissemination and education to more focused efforts utilizing social marketing techniques to change behaviors (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). Applying this social marketing paradigm requires identifying discrete segments of a population and tailoring communication campaign materials to maximize their appeal and potential to change behavior in each one (Lefebvre, 2011; Robinson et al., 2014; Sutton et al., 1995).

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of health communication and social marketing campaigns for addressing many public health challenges, their impact on behaviors associated with substance use outside of tobacco products have been less successful. One meta-analysis of mass media campaigns to prevent drug use noted inconsistent evidence for their effectiveness and could not identify any core features of either successful or unsuccessful campaigns (Allara et al., 2015). Another review of mass media campaigns to reduce alcohol consumption and related harms found that while they can impact knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about alcohol consumption, they do little to reduce consumption itself (Young et al., 2018). Indeed, there is relatively little research to guide the design of campaigns for opioid-related topics and stigma (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). Furlan et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review of the effectiveness of various strategies to reduce OUD and opioid overdose deaths and, based on limited evidence from five studies, found communication campaigns to be one of the most promising strategies.

As communities across the United States continue to grapple with the opioid crisis, communication campaigns have a vital role in increasing awareness and adoption of evidence-based practices (EBPs) to reduce opioid overdose deaths. These EBPs include opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution programs; prescription drug monitoring programs to reduce inappropriate opioid prescribing; Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone; treatment engagement and retention; and recovery support services. Though these EBPs have been shown to reduce opioid misuse and deaths from opioid overdose, their availability is limited in many communities (Williams et al., 2018). Many factors, including stigma and a lack of information about effectiveness, impact community willingness to promote EBPs such as naloxone and MOUD (The HEALing Communities Study Consortium, 2020). Communication campaigns designed to disseminate information, change stigmatizing attitudes, and influence behavior may be an important strategy for increasing availability and utilization of EBPs to treat opioid use disorder (OUD; Lefebvre, 2013; Robinson et al., 2014; Synder and Hamilton, 2002). Evidence also suggests that integrating EBPs with communication campaigns can increase their impact on behavior change. A systematic review of evidence for combining health-related product distribution with mass media campaigns noted that adding campaigns for smoking cessation led to 57 % to 2,500 % increases in calls to existing quit lines, and that smoking cessation rates increased by a median of 10 percentage points among callers who received free nicotine replacement therapy (Robinson et al., 2014).

Building on existing knowledge, this paper describes the overall approach to the development, implementation and evaluation components of a series of communication campaigns as part of a three-pronged intervention, Communities That HEAL (CTH). The Helping End Addictions Long-termSM (HEALing) Communities Study (HCS) is testing whether the CTH intervention can decrease opioid-involved deaths in intervention (n = 34) relative to wait-list (n = 33) communities in four states: Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York and Ohio. Communities randomized to the intervention are referred to as Wave 1 communities, while communities randomized to the waitlist comparison group and later receive the CTH intervention are referred to as Wave 2 communities (The HEALing Communities Study Consortium, 2020). The primary research hypotheses for the communication campaigns are:

-

1

There will be positive associations between higher levels of message dissemination activities and audience information-seeking on the HCS study website.

-

2

The number of campaign messages correctly recognized, and the reported frequency of exposure to these messages, will be positively associated with desired attitudinal outcomes regarding stigma, naloxone distribution, and MOUD treatment.

-

3

Compared to residents in wait-list communities, participants in intervention communities will report significantly lower levels of stigma towards individuals with OUD and greater acceptance of EBPs.

-

4

Self-reported awareness and acceptance of MOUD and opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution programs among residents in intervention communities will significantly increase over time.

In addition to communication campaigns, the CTH includes a community engagement process (Sprague Martinez et al., 2020) and a menu of EBPs to address opioid misuse, treat OUD, and decrease opioid overdose deaths (Winhusen et al., 2020).

1.1. Theoretical model for campaign development and implementation

The campaign approach has three overarching objectives: 1) increase demand for MOUD and naloxone, 2) increase prescribing of MOUD, and 3) increase access to, and availability of, MOUD and naloxone. The behavioral objectives are embedded in a theoretical framework that incorporates core elements of social cognitive theory including enhancing self-efficacy or confidence in performing specific behaviors (such as carrying naloxone or finding a health care provider who can prescribe buprenorphine), increasing positive outcome expectancies (especially that MOUD can be a path to recovery from OUD), and cues to action to stimulate demand for EBPs and individual-level behavior change through information on the HCS website (Bandura, 1986; Riley et al., 2016). Agenda-setting theory was employed to direct coalition attention to how media coverage influences what people think and talk about with each other, and the opinions they have about topics such as acceptance of naloxone and MOUD as well as stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors (McCombs, 2018; Riley et al., 2016).

The analytic framework developed by Robinson et al. (2014) for how media campaigns and health product distribution can be combined to increase behavior change and use of health products was used to guide campaign support of the implementation of EBPs by coalitions in each community. Campaign activities would lead to increased knowledge and self-efficacy, more favorable social norms, greater organizational adoption of EBPs, and improved access to naloxone and MOUD treatment. Consequently, the framework postulates improved attitudes towards the use of naloxone and MOUD, increased use of naloxone and MOUD, and a sustained increase in these behaviors that contributes to a reduction in opioid overdose deaths in the community. Finally, the overall approach rested on a set of evidence-based practices for health communication and social marketing campaigns shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Evidence-Based Communication Campaign Best Practices (from Lefebvre, 2011; McCombs, 2018; Robinson et al, 2014; Snyder, 2007; Wakefield et al., 2010).

| □ | Have behavior change as an explicit goal or objective |

| □ | Use formative research in design and planning |

| □ | Focus on homogeneous population groups |

| □ | Communicate directly with your audience and not just through intermediaries |

| □ | Have multiple executions of messages |

| □ | Have a high frequency of exposure to the messages |

| □ | Use multiple channels |

| □ | Strive for sustained activity to mitigate the observed declines in behavior change after the campaign ends |

| □ | Set an agenda and increase the frequency of conversations about specific health issues within social networks |

| □ | Shift norms in social networks about engaging (or not) in specific health behaviors |

| □ | Prompt public discussions that support or discourage specific health behaviors |

| □ | Incorporate access to products and EBPs as often as possible to enhance their acceptance and use |

The conceptual model for implementation of the CTH communication campaigns was based on the Community-Based Prevention Model (CBPM; Bryant et al., 2007; Mayer et al., 2015), a community-engaged approach to behavior and policy change that involves coalition members in activities such as selecting target behaviors, conducting formative research, working with creative teams to develop and pretest materials, and participating in evaluation activities. The CBPM was adapted for the CTH campaigns into three stages of Prepare, Plan and Implement (i.e., PPI model) in which subject matter experts serve as guides and coaches to community coalition members who are responsible for providing information and feedback at each step in the process.

1.2. Communication and community engagement

Many health communications campaigns have integrated a community engagement or co-creation component to their activities. This approach involves community coalition members in the design and implementation of campaigns rather than relying exclusively on outside experts (Buyucek et al., 2016; Lefebvre, 2013; Mayer et al., 2015). The involvement of community members increases the relevance and responsivity of the campaigns to the unique issues facing each community, including 1) the socio-demographic, linguistic and cultural composition of the community, 2) how social networks and local norms influence behavior, 3) what local policy, structural and social factors may affect access and costs for products and services targeted by campaigns (e.g., availability of naloxone or MOUD), and 4) how organizational structures and policies can impede or enhance behavior change and availability and access to EBPs (Institute of Medicine, 2002; Lefebvre, 2011; Robinson et al., 2014; Wakefield et al., 2010). Examples of successful co-created communication and social marketing campaigns include mental health stigma reduction, heart disease prevention, injury prevention and tobacco control (e.g., Corrigan, 2011; Evers et al., 2013; Friedman et al., 2016; Lefebvre and Flora, 1988; Luque et al., 2007; Ngui et al., 2015; Olawepo et al., 2019; Patten et al., 2018; Reger-Nash et al., 2006; Rudd et al., 1999; Samponga et al., 2017; Slater et al., 2006; Wechsler and Wernick, 1992).

In alignment with the community engagement approach of the CTH intervention model (Sprague Martinez et al., 2020), community coalition members are actively involved in campaign preparation, planning, and implementation. The CTH communication campaign process was designed to provide an opportunity to share knowledge and coordinate activities between communication experts, teams working with community-level challenges in adopting EBPs, community-engagement specialists, and community coalition members.

1.3. Communication and addressing stigma

Stigma is usually conceptualized as a multi-level and cross-sectoral phenomenon that requires a complex intervention approach (Gronholm et al., 2017; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Rao et al., 2019). Reviews of this literature identify forms of stigma that could be targeted by interventions: intrapersonal, or self-stigma; interpersonal stigma; courtesy stigma towards people who have a connection with a person being stigmatized (for example, family members or health care providers of someone with OUD); community, public or social stigma; provider-based stigma (prejudice and discrimination by occupational groups that provide assistance to stigmatized groups); organizational or institutional stigma; and governmental or structural stigma (Gronholm et al., 2017; Heijnders and Van Der Meij, 2006). Messaging that can raise awareness and provide information to stimulate actions to reduce stigma across these various levels of a community are integrated into all communication campaigns (e.g., guidelines for non-stigmatizing language and imagery and information to create stigma-free environments in workplaces and health care settings).

A key priority of CTH communication campaigns is to reduce stigma toward people with OUD and medication stigma. Stigma towards people with OUD includes public attitudes that favor punitive policies toward people with OUD, lack of public support for access to naloxone, negative attitudes towards MOUD, withholding of primary care and other health care services from people with OUD, over-referral to other providers of people with OUD, and patient abandonment (Cooper and Nielsen, 2017; Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan and Nieweglowski, 2018; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Link and Phelan, 2001). Stigma often prevents people with OUD from seeking treatment and receiving the support of friends and family. Medication stigma refers to the belief that using opioid-based medications is substituting one drug for another, and that those who take such medications are not truly abstinent. Tensions between opposing views of the value of MOUD can lead a person seeking treatment or in recovery to not be interested in buprenorphine as an option, hide their use of MOUD from others they believe will disapprove, reduce their dose or stop MOUD in response to peer pressure, or be reluctant to engage in long-term MOUD treatment (Krawczyk et al., 2018).

People with OUD also experience stigma at clinical, structural, and political levels (Cooper and Nielsen, 2017; NAS, 2016) making it difficult for them to seek and access treatment. For example, stigma can be a barrier to the integration of OUD treatment into general medical settings due to fear of being labeled a clinic for “addicts” (National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health, 2017).

There have been a number of communication efforts to reduce stigma towards people with mental illnesses. Reviews of these campaigns have found evidence for small to moderate impacts on stigma-related knowledge, attitudes, and intended behavior, but also found that campaigns often failed to identify goals and objectives and did not reach the intended audiences in a sustained or adequately frequent manner (Gronholm et al., 2017; NAS, 2016). However, there are few studies to guide the design of campaigns for opioid-related stigma (Furlan et al., 2018; NAS, 2016).

2. Method

The impact of the CTH intervention will be tested through a multi-site, parallel group, cluster randomized wait-list controlled trial design (The HEALing Communities Study Consortium, 2020). A total of 67 communities were enrolled across four states and randomly assigned within each state to either the CTH intervention or a wait-list comparison arm. To date, communication campaigns have been developed and implemented in Wave 1 communities. Wave 2 communities will begin campaign activities when they enter the active CTH intervention.

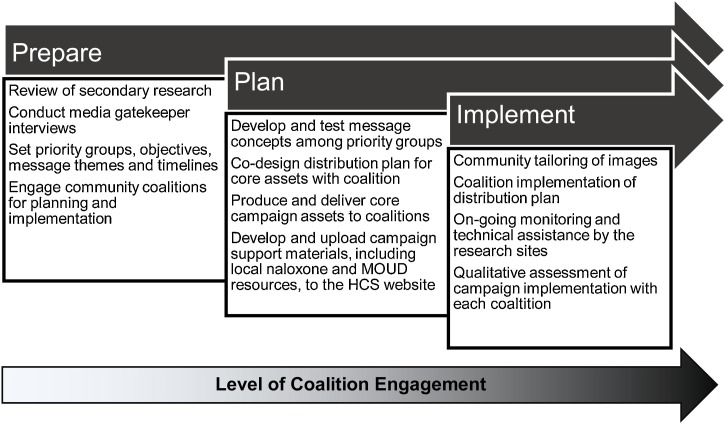

A workgroup of communications experts from the HCS Data Coordinating Center, the research sites, NIDA and SAMHSA, and an outside consultant developed the CTH campaigns and designed the evaluation. The CTH campaigns provided communities with a set of customizable print and media materials (assets), a website linking community members to additional information and local resources related to each campaign theme, and technical assistance for developing and implementing asset distribution plans that included where and how to most effectively place them in communities, how to leverage paid and unpaid social media placements, and strategies for placing op-eds in local print and online news media. This work was conducted across the PPI stages with coalition involvement and responsibilities steadily increasing in the transition from prepare to plan, and plan to implement (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Model and Level of Coalition Engagement for the Design and Implementation of CTH Communication Campaigns.

This partnership between subject matter experts and community coalitions aligns with the CTH community engagement process of co-creating solutions to address OUD and decrease opioid overdose deaths (Sprague Martinez et al., 2020). Applying the PPI stages model across the CTH campaigns ensures standardization of key components of the campaigns across communities (e.g., priority groups, message content, calls to action). The PPI includes coalition participation to ensure campaigns are responsive to the unique needs of each community (e.g., using images that reflect community residents; preparing materials in languages other than English; distributing campaign assets through appropriate community channels).

The content of the CTH campaigns was chosen to promote the implementation of EBPs included in the Opioid Overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA; Winhusen et al., 2020). They include: 1) increase acceptability and demand for EBPs to treat opioid misuse, OUD, and opioid overdose death; and 2) decrease stigma toward people who use opioids, OUD, and EBPs, especially the use of MOUD. Five campaigns are designed to support these goals and will be implemented sequentially over 18 months focused on: 1) obtaining and carrying naloxone; 2) decreasing MOUD stigma; 3) raising awareness of MOUD treatment; 4) staying in MOUD treatment; and 5) a community decision to repeat or refresh previous campaign materials based on results from the Community Evaluation Questionnaire and community perceptions of need. A CTH campaign schedule was developed to harmonize the launch of new campaigns across the communities. The length of each campaign is expected to be approximately three months, and communities can decide whether a campaign remains active longer based on local conditions and public response.

The first three CTH campaigns had three priority audiences: healthcare providers, people with lived experience, and community leaders. Providers included primary care practitioners, nurse prescribers, pharmacists, first responders, emergency department clinicians, and dentists, as well as referral sources. Community leaders included elected officials, such as mayors, city council members, sheriffs, school board members, and aldermen, as well as opinion leaders from local businesses and religious, civic, and community organizations. People with lived experience included people misusing opioids, those with OUD (whether medically diagnosed or not), friends and family, and people in recovery. These three groups were selected because of their vital role in expanding uptake, access, and use of naloxone and MOUD.

2.1. Prepare phase

Activities in the Prepare phase of the campaigns were completed by the communications workgroup in collaboration with subject matter experts developing the ORCCA to ensure alignment of campaign themes and priority groups to facilitate the uptake and implementation of EBPs. Steps included determining campaign objectives, identifying campaign themes and priority groups, and establishing sequencing and timelines for campaigns. A review of existing national, state, and local campaigns on opioid misuse and overdose prevention was done with a structured online search via Google and Google News from July 2019 through September 2019. Two members of the research team independently reviewed the website for each of the 37 identified campaigns and categorized them by 1) the priority group(s) focused on in the campaign (people with lived experience, key opinion leaders, providers, or other); and 2) the topics covered (stigma, general treatment, treatment with MOUD, naloxone, or other). A coding guide was used to define inclusion/exclusion criteria for each audience and topic category, and a third coder reviewed discrepancies to reach a consensus. The key findings were 1) a lack of messaging encouraging demand for MOUD and naloxone, 2) most campaigns focused on the “general public” rather than any key stakeholder groups, and 3) very few were guided by formative research or evaluated.

Based on these data, specific objectives were developed for each campaign that align with priority groups and included: 1) increasing acceptability and demand for MOUD and naloxone among people misusing opioids, those with an OUD, family members, and community leaders; 2) increasing MOUD prescribing among healthcare providers; and 3) increasing awareness of how to access naloxone and MOUD in their community. Stigma objectives cutting across the campaigns were: 1) normalizing possession and use of naloxone; 2) reducing shame and enhancing family and friends’ support of MOUD treatment; 3) increasing acceptance that MOUD can be an essential part of someone’s recovery from OUD; and 4) emphasizing that MOUD improves quality of life.

The Prepare phase included the first contact with community coalitions around campaign planning and implementation. Research site staff engaged community coalitions regarding the communication campaigns including the PPI stages of development and goals. Communication champions (coalition members willing to take a lead role in communication efforts) and, in some cases, designated coalition subcommittees were identified to work on communication campaigns. Structured interviews were conducted with media gatekeepers (e.g., journalists, reporters, publishers and editors of local news outlets, bloggers, podcast hosts, public information officers at local government agencies) to understand the local media landscape and coverage of opioid issues in each community.

2.2. Plan phase

Community coalition engagement with communication campaign activities increased in the Plan phase. The communications workgroup, along with copywriters and graphic designers, developed several versions of message content for each of the first three campaigns in the form of taglines (i.e., text reflecting campaign themes to attract viewer’s attention), calls to action (i.e., desired behaviors in response to the message), and visual images. These options were tested with representatives from priority groups in communities to provide feedback on: 1) comprehension, appeal, and acceptability of the message content; 2) ideas about the best approaches for disseminating materials; and 3) perceived challenges to the acceptance of the materials and messages in the communities. All recruitment materials, informed consent forms, interview guides and other aspects of the protocol were reviewed and approval by Advarra Inc., the HEALing Communities Study single Institutional Review Board (Pro00038088).

The four research sites recruited people representing each priority group from their Wave 1 communities through recommendations from study staff, community advisory board members, and coalitions. For some priority groups that proved more difficult to recruit, snowball sampling and a professional market research panel specializing in health care providers were used. An experienced moderator conducted individual interviews of 30−45 min using video conference and a structured interview guide. Transcripts were analyzed using QSR International’s NVivo 11.0 (QSR International, 2015) to organize, identify, and analyze themes from the interviews.

A total of 67 community leaders, 37 healthcare providers, and 35 persons either diagnosed with OUD (n = 15), in long-term recovery (n = 8), or a family member of someone with OUD or in recovery (n = 12) completed an interview. The campaign planning committee reviewed topline findings and recommendations to identify common themes that guided the selection, revision, and finalization of message concepts for the campaigns.

The results of the message testing, and recommendations from experienced public health communication campaign strategists, were used by two creative teams of copywriters and graphic designers to produce a core set of communication assets for each of the three priority groups and campaigns. The core campaign assets included: 1) two versions of digital products that could be used as paid advertisements or social media placements, and 2) two formats of print materials that could be used in paid advertising, direct distribution in the form of flyers or palm cards in specific venues, or placement in locations around the community. All assets included a unique URL directing viewers to their community specific webpage that included educational material on naloxone, stigma, and MOUD; links to and contact lists of local resources for naloxone and MOUD; local study and/or coalition contact information; and an opportunity to sign up to receive email updates about the HCS.

Communication champions and community coalitions were extensively involved in the development of distribution plans for the core assets of each campaign. Research site staff facilitated discussions and meetings with community coalitions and other key stakeholders about how to best distribute assets in their community - including past practices and successes from other communication efforts. Research staff then guided community participants through a set of steps to develop distribution plans for each priority group including communication channels (i.e., media campaign messages sent to different priority groups) and touchpoints (i.e., physical settings and community organizations that the priority groups come into contact with in everyday life). Distribution planning also included identifying budgetary needs for paid media that were managed by each coalition. This planning involved an iterative process where communities could identify additional priority groups, campaign materials and formats, community partners, and distribution channels, and adapt the campaigns and messaging appropriately in the event of local, state, or national events (Covid-19, for example).

2.3. Implement phase

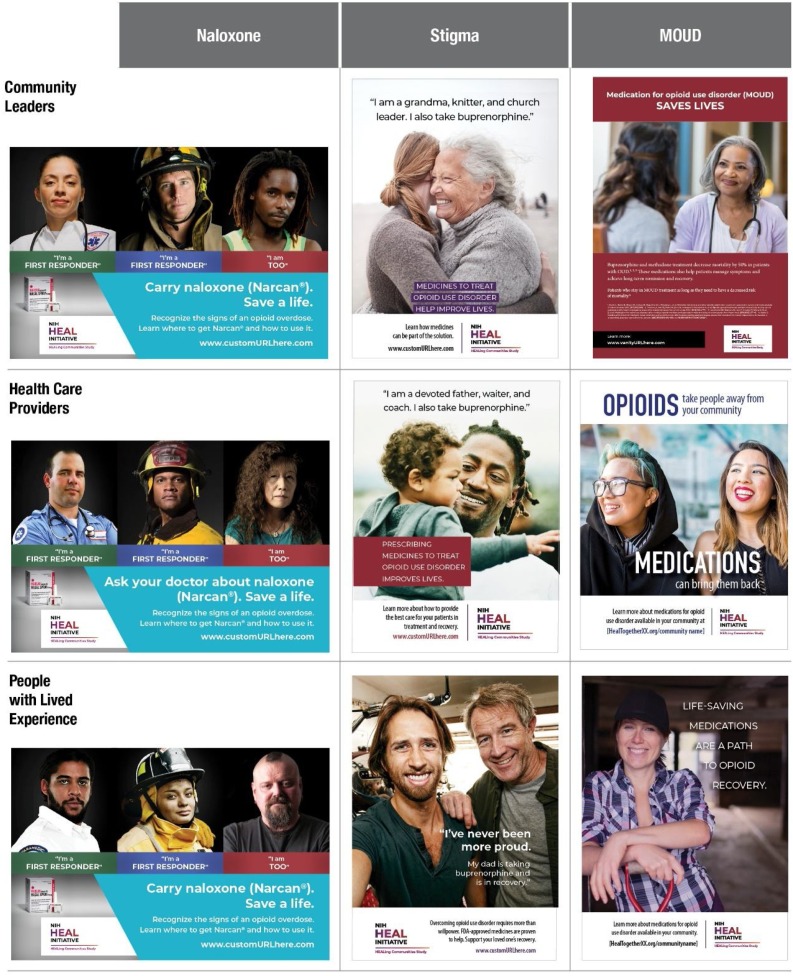

Community coalitions and local stakeholders are responsible for the Implement stage of the PPI model. Campaign assets for obtaining and carrying naloxone, decreasing MOUD stigma, and raising awareness of MOUD treatment are provided to communities with stock photography images, English-language text, a community-specific URL, and a broad HCS logo (see Fig. 2 for examples of core print materials for the Naloxone, MOUD stigma, and MOUD treatment campaigns).

Fig. 2.

Examples of Core Print Materials Developed for Each of Three Priority Groups in the CTH Naloxone, Stigma and MOUD Campaigns.

The assets are packaged with customization tools that allowed community coalitions to make some modifications but not change the message. Communities can exchange their own logos for the HCS logo and insert community-generated images to better represent their communities and priority groups, including different racial/ethnic or sociodemographic groups. Community coalitions can make minor modifications to the text to reflect their ORRCA priorities such as editing a campaign asset about general MOUD to focus on a specific one, e.g., buprenorphine or methadone. Some coalitions also choose to add QR codes instead of the URL that, when scanned, direct people to the local community web page. Research sites and communities can also translate campaign materials to languages other than English to meet the needs of the community. Core campaign assets and messages can also be adapted to other media formats (e.g., billboards, transit advertisements) that are consistent with their distribution plan.

The communications workgroup created a set of campaign “playbooks” outlining: 1) best practices for implementing a campaign; 2) how to create a campaign distribution plan; 3) how to pitch, place and leverage op-eds, letters to the editor, and interviews on digital and traditional media platforms; 4) how to plan communication around key topics and events in the community; and 5) how to engage community businesses and other organizations with the campaigns and other coalition activities. In addition, message guidance documents were developed for each campaign to help coalitions develop additional campaign materials such as video testimonials of people in recovery or providers of MOUD, newspaper editorials and radio scripts, social media posts, and talking points for television coverage featuring local news or human-interest stories.

Informal qualitative assessments were conducted either through interviews or the completion of a brief questionnaire with communication champions and coalition members in each community involved in the implementation of the campaign. These assessments were held 4–6 weeks after the launch date of each campaign to identify challenges, problem solve, capture lessons learned, and chart steps for subsequent campaigns. Reports generated from these mid-course assessments were reviewed by the research site staff and coalition members to guide modifications or adjustments to the campaign distribution plans or implementation.

3. Campaign evaluation

Measuring implementation fidelity for each campaign includes tracking of 1) distribution planning; 2) campaign launch and assessment; and 3) the completion of distribution plan activities by each coalition. An evaluation of the CTH campaigns will test the four research hypotheses outlined earlier.

The campaign evaluation protocol and all participant recruitment materials, informed consent forms, incentives and other materials were reviewed and approval by Advarra Inc., the HEALing Communities Study single Institutional Review Board (Pro00038088). Residents in HCS communities are recruited through Facebook and Instagram advertisements to participate in cross-sectional surveys and can choose to continue to participate in a longitudinal survey. The Community Evaluation Questionnaire includes questions about: 1) recognition of the HCS campaign materials (Livingston et al., 2013); 2) knowledge about MOUD, opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution programs, and barriers to adoption; 3) measures of personal stigma (Griffiths et al., 2008; Lefebvre et al., 2019); 4) measures of stigma towards MOUD providers (Lefebvre et al., 2019); 5) measures of self-efficacy (Lefebvre et al., 2019; Saunders et al., 1997); 6) measures of social distance (i.e., community stigma) developed for use in this study; 7) perceived message effectiveness (Brewer et al., 2016); 8) personal behaviors regarding OUD, naloxone, and treatment (Livingston et al., 2013); 9) personal experience with OUD (Livingston et al., 2013); and 10) respondent demographic questions.

The baseline survey was administered prior to the launch of the first campaign that promoted obtaining and carrying naloxone. Follow-up cross-sectional surveys are administered approximately 2–3 weeks before each campaign is scheduled to end. Participants in the baseline survey who indicated they could be contacted for follow-up surveys are notified by email of the opportunity to participate in a separate longitudinal survey that occurs at the same time as the cross-sectional ones and uses the identical instrument. Data from the Community Evaluation Questionnaire, tracking of the distribution of campaign materials, and analytics of each community page on the website will be used to test the main hypotheses.

4. Discussion

The HCS is an ambitious implementation study in the field of addiction science (Chandler et al., 2020). The communication campaigns play an integral role in the CTH intervention with the goal of increasing the acceptability and demand for EBPs and reducing stigma toward opioid use, OUD, and MOUD. As of the publication of this paper, the first two campaigns have been implemented, the third is in the Prepare phase and campaigns four and five are in the Plan phase.

HCS is also the largest empirical study of community-based communication campaigns intended to impact behavioral change across 67 diverse communities. Adapted from best practices for communication campaigns and social marketing in other areas of public health (c.f., Farrelly et al., 2005; Randolph and Viswanath, 2004; Wong et al., 2004), the CTH campaigns embrace engagement with community coalitions to tailor and implement a set of campaigns that are aligned with other CTH intervention components.

Engaging communities in the development and implementation of campaigns provides them with opportunities to develop potentially sustainable solutions to the opioid crisis that are tailored to the unique context of their community (Gloppen et al., 2016; Lefebvre, 2013). Communication campaign objectives, priority groups, and core messages were developed by research sites in the context of the HCS research objectives and using health communication and social marketing best practices. Community coalitions adapt campaign assets and develop distribution plans accounting for several factors including: 1) the specific composition, needs, and communication channels available in their communities; 2) readiness and technical expertise among community coalitions and their partners; 3) and the creativity and capacity of people in each community to extend the campaigns beyond the core assets to include other products and media channels.

Campaign assets, distribution plans, and other resources were designed to be responsive to the local context. This was important as communities began to be impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, initial distribution plans for the naloxone campaign included placing print materials in heavily trafficked community locations such as libraries, local businesses, and government agencies; and directly handing out flyers at highly attended events like county fairs or fireworks displays. Pandemic mitigation strategies including sheltering in place, closing of businesses and governmental agencies, and the cancellation of large group events meant community champions and coalitions had to quickly pivot to other strategies to distribute campaign materials. In response, the research sites worked with community coalitions to shift advertising placements and redirect distribution of campaign assets to social and digital media platforms.

Community coalition involvement, creativity, confidence, and enthusiasm has grown over each of the three campaigns launched to date. These exciting byproducts of the CTH campaigns will hopefully ensure campaigns are seen and heard by priority groups, contribute to expanding EBP availability and use in each community, and lead to sustained communication activities by the coalitions. The campaign evaluation will allow us to determine if and how exposure to each campaign leads to changes in attitudes, intentions, and behaviors related to opioid use, OUD, and MOUD. If successful, the CTH campaigns will extend the evidence base for how to design and implement effective community-engaged campaigns to address the opioid crisis and improve public health.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04111939).

Funding source

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the NIH HEAL Initiative with the following awards:

RTI International: UM1DA049394.

University of Kentucky: UM1DA049406.

Boston Medical Center: UM1DA049412.

Columbia University: UM1DA049415.

The Ohio State University: UM1DA049417.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the NIH HEAL Initiative, or the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Authorship contributions

All authors were involved in the conceptualization, methodology and project management of the work described in this manuscript. Writing of the original draft included Lefebvre, Chandler, Helme, Beard, Burrus, Hedrick, Lewis, and Rodgers. All authors were involved in the review and editing of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the many members of the community coalitions and Community Advisory Boards who have been involved in this project and are integral to its eventual success; our colleagues who support the other aspects of the CTH intervention; and the creative and digital services groups at RTI and ORAU who have produced the campaign, social media and web assets described in this paper.

References

- Allara E., Ferri M., Bo A., Gasparrini A., Faggiano F. Are mass-media campaigns effective in preventing drug use? A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J.A., Duke J.C., Davis K.C., Kim A.E., Nonnemaker J.M., Farrelly M.C. Using mass media campaigns to reduce youth tobacco use: a review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2015;30:e71–e82. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130510-LIT-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala M.M., Strzeszynski L., Topor‐Madry R. Mass media interventions for smoking cessation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004704.pub4. Issue 11. Art. No.: CD004704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer N.T., Hall M.G., Lee J.G., Peebles K., Noar S.M., Ribisl K.M. Testing warning messages on smokers’ cigarette packages: a standardized protocol. Tob. Control. 2016;25:153–159. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant C.A., Brown K.R., McDermott R.J., Forthofer M.S., Bumpus E.C., Calkins S.A., Zapata L.B. Community-based prevention marketing: organizing a community for health behavior intervention. Health Promot. Pract. 2007;8:154–163. doi: 10.1177/1524839906290089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyucek N., Kubacki K., Rundle-Thiele S., Pang B. A systematic review of stakeholder involvement in social marketing interventions. Australas. Mark. J. 2016;24:8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S., Nielsen S. Stigma and social support in pharmaceutical opioid treatment populations: a scoping review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017;15:452. doi: 10.1007/s11469-016-9719-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am. Psychol. 2004;59:614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P.W. Best practices: strategic stigma change (SSC): five principles for social marketing campaigns to reduce stigma. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011;62:824–826. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.8.pss6208_0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P.W., Nieweglowski K. Stigma and the public health agenda for the opioid crisis in America. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2018;59:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin S., Brennan E., Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob. Control. 2012;21:127–138. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers U., Jones S.C., Iverson D., Caputi P. ‘Get your Life Back”: process and impact evaluation of an asthma social marketing campaign targeting older adults. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:759. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly M.C., Davis K.C., Haviland M.L., Messeri P., Healton C.G. Evidence of a dose—response relationship between “truth” antismoking ads and youth smoking prevalence. Am. J. Public Health. 2005;95:425–431. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestone R., Rowe C.J., Modi S.N., Sievers D. The effectiveness of social marketing in global health: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:110–124. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A.L., Kachur R.E., Noar S.M., McFarLane M. Health communication and social marketing campaigns for sexually transmitted disease prevention and control: what is the evidence of their effectiveness? Sex. Transm. Dis. 2016;43:S83–S101. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan A.D., Carnide N., Irvin E., Van Eerd D., Munhall C., Kim J., Li C.M.F., Hamad A., Mahood Q., MacDonald S. A systematic review of strategies to improve appropriate use of opioids and to reduce opioid use disorder and death from prescription opioids. Can. J. Pain. 2018;2:218–235. doi: 10.1080/24740527.2018.1479842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloppen K.M., Brown E.C., Wagenaar B.H., Hawkins J.D., Rhew I.C., Oesterle S. Sustaining adoption of science-based prevention through communities that care. J. Commun. Psychol. 2016;44:78–89. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths K.M., Christensen H., Jorm A.F. Predictors of depression stigma. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronholm P.C., Henderson C., Deb T., Thornicroft G. Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: the state of the art. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017;52(3):249–258. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1341-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M.L., Phelan J.C., Link B.G. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103:813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnders M., Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: an overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2006;11:353–363. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helme D.W., Savage M., Record R. In: Health Communication: Theory, Method, and Application. 1st ed. Harrington N., editor. Routledge; New York, NY: 2014. Health communication campaigns and interventions; pp. 397–427. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2002. Speaking of Health: Assessing Health Communication Strategies for Diverse Populations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk N., Negron T., Nieto M., Agus D., Fingerhood M.I. Overcoming medication stigma in peer recovery: a new paradigm. Subst. Abus. 2018;39:404–409. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1439798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre R.C. An integrative model for social marketing. J. Soc. Mark. 2011;1:54–72. doi: 10.1108/20426761111104437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre R.C. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2013. Social Marketing and Social Change: Strategies and Tools for Improving Health, Well-being, and the Environment. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre R.C., Squiers L.B., Adams E., Nyblade L., West S., Bann C.M. Stigma and prescription opioid addiction and treatment. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019;53:S401. [Google Scholar]

- Link B.G., Phelan J.C. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston J.D., Tugwell A., Korf-Uzan K., Cianfrone M., Coniglio C. Evaluation of a campaign to improve awareness and attitudes of young people towards mental health issues. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013;48:965–973. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque J.S., Monaghan P., Contreras R.B., August E., Baldwin J.A., Bryant C.A., McDermott R.J. Implementation evaluation of a culturally competent eye injury prevention program for citrus workers in a Florida migrant community. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(4):359–369. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A.B., Lefebvre R.C., McDermott R.J., Bryant C.A., Courtney A.H., Lindenberger J.H., Swanson M.A., Panzera A.D., Khaliq M., Biroscak B.J., Wright A.P., et al. In: Behavior Change Models: Theory and Application for Social Marketing. Brennan L., editor. Edward Elgar Publishers; Cheltenham, UK: 2015. A social marketing approach for increasing community coalitions’ adoption of evidence-based policy to combat obesity; pp. 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs M. second ed. 2018. Setting the Agenda: Mass Media and Public Opinion. Cambridge, England. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . National Academies Press; Washington, D.C: 2016. Ending Discrimination Against People With Mental and Substance Use Disorders. The Evidence for Stigma Change. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health . 2017. Report on Lessons Learned From Rural Opioid Overdose Reversal Grant Recipients.https://nosorh.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ROOR-Report-1.pdf Accessed August 20, 2020 at. [Google Scholar]

- Ngui E., Hamilton C., Nugent M., Simpson P., Willis E. Evaluation of a social marketing campaign to increase awareness of immunizations for urban low-income children. WMJ. 2015;114:10–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar S.M., Palmgreen P., Chabot M., Dobransky N., Zimmerman R.S. A 10-year systematic review of HIV/AIDS mass communication campaigns: have we made progress? J. Health Commun. 2009;14:15–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730802592239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olawepo J.O., Pharr J.R., Kachen A. The use of social marketing campaigns to increase HIV testing uptake: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2019;31:153–162. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1533631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten C.A., Lando H., Resnicow K., Decker P.A., Smith C.M., Hanza M.M., Burhansstipanov L., Scott M. Developing health communication messaging for a social marketing campaign to reduce tobacco use in pregnancy among Alaska Native women. J. Commun. Health. 2018;11:252–262. doi: 10.1080/17538068.2018.1495929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph W., Viswanath K. Lessons learned from public health mass media campaigns: marketing health in a crowded media world. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2004;25:419–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D., Elshafei A., Nguyen M., Hatzenbuehler M.L., Go V.F. A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: state of the science and future directions. BMC Med. 2019;17:41. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1244-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger-Nash B., Fell P., Spicer D., Fisher B.D., Cooper L., Chey T., Bauman A. BC walks: replication of a communitywide physical activity campaign. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley W.T., Martin C.A., Rivera D.E., Hekler E.B., Adams M.A., Buman M.P., Pavel M., King A.C. Development of a dynamic computational model of social cognitive theory. Transl. Behav. Med. 2016;6:483–495. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0356-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M.N., Tansil K.A., Elder R.W., Soler R.E., Labre M.P., Mercer S.L., Eroglu D., Baur C., Lyon-Daniel K., Fridinger F., Sokler L.A., Green L.W., Miller T., Dearing J.W., Evans W.D., Snyder L.B., Viswanath K.K., Beistle D.M., Chervin D.D., Bernhardt J.M., Rimer B.K. Mass media health communication campaigns combined with health-related product distribution: a community guide systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014;47:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd R.E., Goldberg J., Dietz W. A five-stage model for sustaining a community campaign. J. Health Commun. 1999;4:37–48. doi: 10.1080/108107399127084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samponga G., Bakolis I., Evans-Lacko S., Robinson E., Thornicroft G., Henderson C. The impact of social marketing campaigns on reducing mental health stigma: results from the 2009-2014 time to change programme. Eur. Psychiatry. 2017;40:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders R.P., Pate R.R., Felton G., Weinrich M.C., Ward D.S., Parsons M.A., Baranowski T. Development of questionnaires to measure psychosocial influences on children’s physical activity. Prev. Med. 1997;26:241–247. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater M.D., Kelly K., Edwards R., Plested B., Thurman P.J., Keefe T., Lawrence F., Henry K. Combining in-school and participatory, community-based media efforts: reducing marijuana and alcohol uptake among younger adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 2006;21:157–167. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder L.B. Health communication campaigns and their impact on behavior. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2007;39:S32–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague Martinez L., Rapkin B.D., Young A., Freisthler B., Glasgow L., Hunt T., Salsberry P., Oga E.A., Bennet-Fallin A., Plouck T.J., Drainoni M.-L., Freeman P.R., Surratt H., Gulley J., Hamilton G.A., Bowman P., Roeber C.A., El-Bassel N., Battaglia T. Community engagement to implement evidence-based practices in the HEALing Communities Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton S.M., Balch G.I., Lefebvre R.C. Strategic questions for consumer-based health communications. Public Health Rep. 1995;110:725–733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synder L.B., Hamilton M.A. In: Public Health Communication: Evidence for Behavior Change. Hornik R.C., Erlbaum N.J., editors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. A meta-analysis of U.S. health campaign effects on behavior: emphasize enforcement, exposure, and new information, and beware the secular trend; pp. 357–384. [Google Scholar]

- The HEALing Communities Study Consortium HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Communities Study: protocol for a cluster randomized trial at the community level to reduce opioid overdose deaths through implementation of an Integrated set of evidence-based practices. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield M.A., Loken B., Hornik R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behavior. Lancet. 2010;376:1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H., Wernick S.M. A social marketing campaign to promote low-fat milk consumption in an inner-city Latino community. Public Health Rep. 1992;107:202–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A.R., Nunes E.V., Bisaga A., Pincus H.A., Johnson K.A., Campbell A.N., Remein R.H., Crystal S., Friedmann P.D., Levin F.R., Olfson M. Developing an opioid use disorder treatment cascade: a review of quality measures. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2018;91:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen T., Walley A., Fanucchi L.C., Hunt T., Lyons M., Lofwall M., Brown J.L., Freeman P.R., Nunes E., Beers D., Saitz R., Stambaugh L., Oga E.A., Herron N., Baker T., Cook C.D., Roberts M.F., Alford D.P., Starrels J.L., Chandler R.K. The Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA): Evidence-based practices in the HEALing Communities Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong F., Huhman M., Heitzler C., Asbury L., Bretthauer-Mueller R., McCarthy S., Londe P. VERB - a social marketing campaign to increase physical activity among youth. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2004;1:A10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young B., Lewis S., Vittal Katikireddi S., Bauld L., Stead M., Angus K., Campbell M., Hilton S., Thomas J., Hinds K., Ashie A., Langley T. Effectiveness of mass media campaigns to reduce alcohol consumption and harm: a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53:302–316. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agx094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]