Abstract

Emerging evidence regarding COVID-19 highlights the role of individual resistance and immune function in both susceptibility to infection and severity of disease. Multiple factors influence the response of the human host on exposure to viral pathogens. Influencing an individual’s susceptibility to infection are such factors as nutritional status, physical and psychosocial stressors, obesity, protein-calorie malnutrition, emotional resilience, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, environmental toxins including air pollution and firsthand and secondhand tobacco smoke, sleep habits, sedentary lifestyle, drug-induced nutritional deficiencies and drug-induced immunomodulatory effects, and availability of nutrient-dense food and empty calories. This review examines the network of interacting cofactors that influence the host-pathogen relationship, which in turn determines one’s susceptibility to viral infections like COVID-19. It then evaluates the role of machine learning, including predictive analytics and random forest modeling, to help clinicians assess patients’ risk for development of active infection and to devise a comprehensive approach to prevention and treatment.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AI, artificial intelligence; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ML, machine learning; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Article Highlights.

-

•

The emerging field of network medicine can shed light on the interplay between microbial virulence and the ability of an individual’s immune system to defend against full-blown clinical disease.

-

•

Network medicine examines the diverse biologic systems that influence the pathogenesis of disease, rather than focusing on a reductionistic approach that relies on 1 or 2 organ systems that are typically considered for each disorder.

-

•

“With the growth of large data sets comprising detailed and comprehensive information about the genome, the transcriptome, the proteome, the metabolome, and the exposome, biomedical research has reached a stage at which specific disease-causing events can be explored and understood in integrated context.”

-

•

Among the specific agents that influence an individual’s susceptibility to infection are nutritional status, physical and psychosocial stressors, obesity, protein-calorie malnutrition, emotional resilience, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and environmental toxins including air pollution and firsthand and secondhand tobacco smoke.

-

•

Employing machine learning–enhanced algorithms to analyze all the aforementioned risk factors and their interactions may help determine which ones predict a patient’s risk of COVID-19 or the prognosis of someone who has already tested positive.

COVID-19 continues to challenge health care providers and policymakers alike. In many respects, the infection shares the features of most other viral infections. However, the rapidity of its spread and its ability to nearly overwhelm health care delivery around the globe have startled many health officials and world leaders.

Public health specialists have responded to the threat, emphasizing the need for a vaccine, antiviral agents, protective equipment, and social distancing. Whereas these tactics remain top priorities, they have eclipsed a fundamental tenet of microbiology: the risk for development of any infection is determined by both the virulence of the pathogen and the resistance of the human host. Much has been written about microbial virulence, but little attention has been devoted to the factors that allow humans to resist infection. Experts have pointed to evidence to show that resistance to COVID-19 is influenced by coexisting diseases and age, but resistance is also dependent on numerous other cofactors.

The emerging field of network medicine can shed light on the interplay between microbial virulence and the ability of an individual’s immune system to defend against full-blown clinical disease. Over the centuries, medicine has been dominated by a reductionistic approach to causality, a divide-and-conquer paradigm “rooted in the assumption that complex problems are solvable by dividing them into smaller, simpler, and thus more tractable units.”1 Although this methodology has generated countless rewards, it has limitations. Reductionistic thinking has led researchers to search for 1 or 2 root causes of each disease and to design therapies that only address these causes. When human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was found to cause AIDS, for instance, virtually all efforts then focused on suppressing the virus; the same has held true for many infectious disorders. However, although HIV infection is undoubtedly the necessary cause of AIDS, it is not the sole and sufficient cause, as evidenced by the fact that many are exposed to the virus without contracting AIDS. These “anomalies” imply that there are cofactors that contribute to the onset of clinical disease. Detecting these entities requires the reductionist approach to be complemented by network medicine, which takes a more wholistic direction, looking at a wide range of synergistic covariates.

Network medicine examines the diverse biologic systems that influence the pathogenesis of disease rather than focusing on 1 or 2 organ systems that are typically considered for each disorder. The emergence of big data and supercomputers has given investigators insights into these networks or “nodes.” With the assistance of advanced machine learning (ML)–based algorithms, these advances are revealing new causal relationships. Joseph Loscalzo, MD, chair of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, describes this paradigm shift: “With the growth of large data sets comprising detailed and comprehensive information about the genome, the transcriptome, the proteome, the metabolome, and the exposome, biomedical research has reached a stage at which specific disease-causing events can be explored and understood in integrated context.”2 Once a list of suspected covariates has been identified, deep learning algorithms have the ability to judge the strengths and weaknesses of each to determine their relative weights as contributing agents.

Among the specific agents that influence an individual’s susceptibility to infection are nutritional status, physical and psychosocial stressors, obesity, protein-calorie malnutrition, emotional resilience, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and environmental toxins including air pollution and firsthand and secondhand tobacco smoke. Other variables that are likely to increase a person’s susceptibility to infection include sleep habits, sedentary lifestyle, drug-induced nutritional deficiencies and drug-induced immunomodulatory effects, availability of nutrient-dense food and empty calories, and availability of science-based educational materials about the microbe in question.

To implement a network-based approach to the current pandemic, our review examines the evidence on how specific cofactors influence host-pathogen interactions, which in turn determine one’s susceptibility to viral infections like COVID-19. It then evaluates the role of ML, including predictive analytics, to help clinicians assess patients’ risk for development of active infection and to help devise a comprehensive approach to prevention and treatment.

Root Cause Analysis and Network Medicine

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the root cause of COVID-19, is a betacoronavirus that originated in bats.3 The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at the University of Oxford reviewed 21 analyses and found that between 5% and 80% of patients who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 may be asymptomatic.4 The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 80% of COVID-19–positive patients experience mild to moderate signs and symptoms and do not require hospitalization.5 Johns Hopkins University estimates that the observed case-fatality rate for the infection varies from 5.9% in the United States to 16.2% in Belgium as of May 25, 2020.6 These statistics imply that as with many other viral infections, not everyone becomes seriously ill with COVID-19. They also strongly suggest that there are cofactors that determine the impact of the virus, illustrating the complex interplay between the virus and its host.

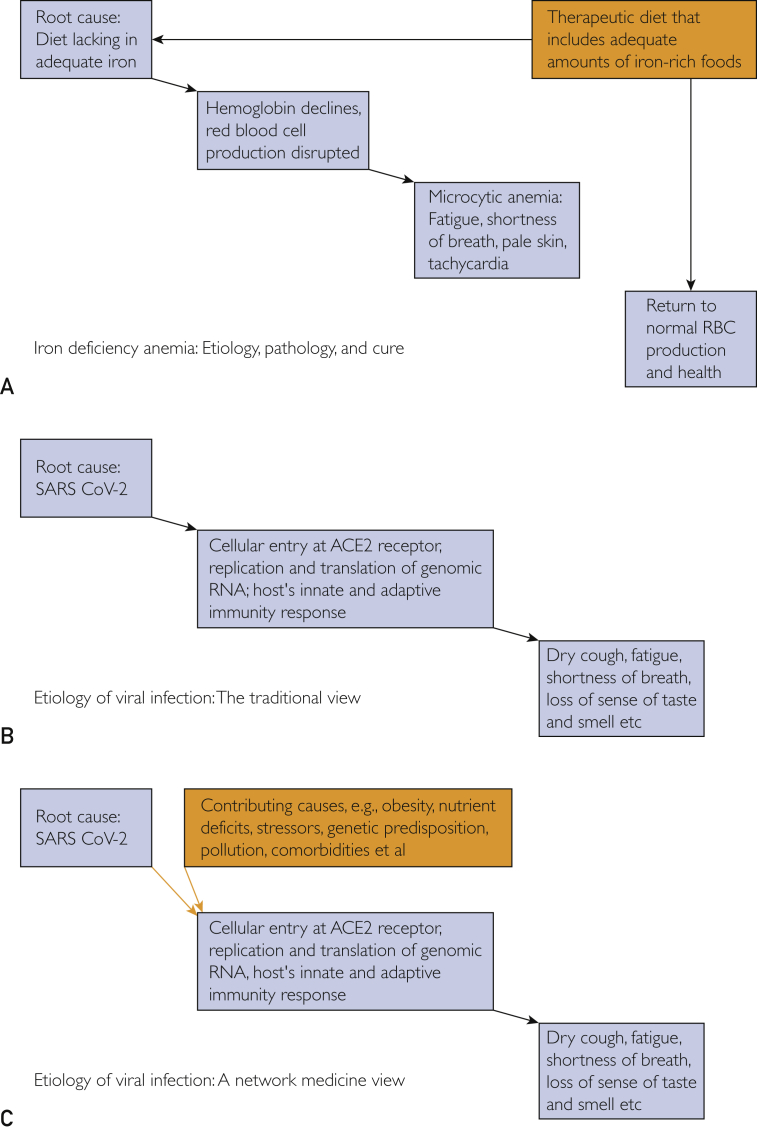

These interactions do not readily lend themselves to the reductionistic approach. The reductionistic paradigm is ideal for deciphering the cause and the definitive treatment of many acute disorders. Ahn et al7 explained, “Diseases such as urinary tract infection, acute appendicitis, or aortic dissection are driven primarily by a single pathology amenable to a specific intervention. … Reductionism works best when an isolatable problem exists and where a quick and effective solution is needed.” Reductionism is also effective in many simple straightforward conditions like diet-induced iron deficiency, as illustrated in Figure A. However, the approach is inadequate when one attempts to understand the etiology of diseases in which the root cause is intermingled with numerous contributing covariates that determine whether it remains asymptomatic or advances into clinical presentation.

Figure.

A reductionistic approach is an effective way to decipher the etiology of many simple straightforward conditions like diet-induced iron deficiency, as illustrated in A. However, the approach is inadequate when one attempts to understand the etiology of diseases in which the root cause is intermingled with numerous contributing covariates that determine whether it remains asymptomatic or advances into clinical presentation. In such cases, a network medicine approach is more effective because it takes into account numerous metabolic, environmental, and genetic factors that affect multiple organ systems. The differences between these 2 paradigms are illustrated in B and C, which depict the traditional way to understand the etiology of viral infection and the networks-based approach. ACE2 = angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; RBC = red blood cell; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. (A adapted from Cerrato P, Halamka J. Realizing the Promise of Precision Medicine. San Diego, CA: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2018.)

In such circumstances, network medicine offers new insights and therapeutic options. Essentially, this paradigm redefines health and disease, replacing the Osler approach that relies on clinicopathologic correlation to postulate pathogenesis and views individual diseases as the consequences of pathologic events in specific organ systems.2 That paradigm implies that diabetes is solely a pancreatic disease, myocardial infarction is only a cardiac disease, and infections are solely the result of the presence of the infectious agent in a specific organ system. A networks approach suggests that many such disorders are systemic in origin and are the consequences of numerous metabolic, environmental, and genetic factors that affect multiple organ systems. The difference between these 2 paradigms is illustrated in Figure B and C, depicting the traditional etiology of viral infection and a networks-based approach.

Identifying Infectious Cofactors

If viral infections like COVID-19 are the result of the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and numerous cofactors, which cofactors should we concentrate on? Considerable attention has been given to hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease as risk factors for COVID-19, but until recently, little has been written about obesity. A recent Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that analyzed characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in 14 states found that “among patients aged 50–64 years, obesity was [the] most prevalent” underlying medical condition.8 Because obesity induces a low-level chronic inflammatory state, that inflammation probably reduces one’s ability to fight infection. That assertion is supported by the observation that COVID-19 patients are more likely to require mechanical ventilation if they are obese. Among 124 infected patients admitted to an intensive care unit, almost half (47.6%) had a body mass index above 30 kg/m2.9 That evidence, coupled with several other studies and case reports, has established obesity as a risk factor for the infection.10 At the other end of the dietary spectrum, protein-calorie malnutrition compromises a person’s immune system through several mechanisms, including disruption of antibody production.

Similarly, there is mounting evidence to suggest that vitamin D deficiency contributes to COVID-19 infection. Investigators have found that among 212 patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2, “vitamin D status is significantly associated with clinical outcomes.”11 A meta-analysis that evaluated the effects of vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections concluded that “vitamin D supplementation was safe and it protected against acute respiratory tract infection overall.”12 Daneshkhah et al,13 in a yet to be peer-reviewed analysis, also found evidence that links vitamin D deficiency to COVID-19 mortality and postulated that the prohormone may suppress the cytokine storm observed in these patients. They found a correlation between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the adaptive average of time-adjusted case-mortality ratio in countries that used similar screening approaches to vitamin D status (United States, France, and United Kingdom) with an inverse correlation coefficient of −0.84 to −1. The researchers also detected a correlation between C-reactive protein—a surrogate marker for cytokine storm—and vitamin D deficiency in this population of patients. Although some of this preliminary evidence implies that vitamin D supplementation may have merit, correlations between low vitamin D levels and COVID-19 mortality may suggest that a diet rich in the nutrient along with adequate exposure to sunlight is equally protective, thus negating the need for supplementation.

Zinc is also involved in maintaining normal immune functioning, including a pivotal role in regulating signaling pathways in both innate and adaptive immune cells.14 The trace element binds to metallothioneins, for instance, which play an important role in immune response.15 Similarly, the detrimental effects of zinc deficiency on the immune system have been well documented for decades, affecting approximating 2 billion persons worldwide.14,16 To date, there is no direct evidence demonstrating that patients at risk for COVID-19 have a zinc deficit, but a lack of zinc has been shown to contribute to viral infections, including HIV infection and hepatitis C.16 Between 8 and 11 mg of zinc17 will prevent the clinical effects of a zinc deficiency and its impact on immune functioning. That dose is available from a well-balanced diet, also negating the need for supplementation in most adults, with the exception of patients with an acquired malabsorption syndrome or rare genetic disorders like acrodermatitis enteropathica, the result of a mutation that encodes a protein that binds zinc. Clinicians who are inclined to recommend zinc supplements, on the other hand, need to differentiate between the physiologic effects of small doses of the nutrient and the pharmacologic effect of larger doses. Once zinc-dependent enzymes are saturated, the nutrient can have unintended effects, including the displacement of copper, which explains why high doses of zinc have been shown to cause copper deficiency–induced anemia, which in itself can compromise one’s ability to resist infection.18

Numerous studies have also established a relationship between stress and immune dysfunction. In fact, the evidence linking the two has been strong enough to give birth to its own specialty: psychoneuroimmunology. Chronic stress in particular has been associated with elevated proinflammatory cytokines, and COVID-19 has been linked to cytokine storm. It is likely that the risk of viral infection caused by chronic stress is mediated through the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. This pathway also contributes to the lack of responsiveness to antiviral vaccines in both men and women who are stressed out from caring for a spouse with dementia.19 Glaser and Kiecolt-Glaser19 summed up the contribution of stress: “…human and animal studies show that stress can modulate the steady-state expression of latent HSV [herpes simplex virus], EBV [Epstein-Barr virus] and CMV [cytomegalovirus], downregulating the specific T-cell response to the virus to an extent that is sufficient to result in viral reactivation.”

The association between a sedentary lifestyle and the risk of infection has likewise been established. The evidence suggests that moderate to vigorous physical activity reduces the risk of upper respiratory tract infection.20,21

Because genetic predisposition contributes to many infectious diseases, investigators are looking for genomic fingerprints that help predict clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Although it is too early in the pandemic for any definitive conclusions to be drawn, there are several findings worth consideration. There are data that implicate genetic variants in the HLA system—including HLA-B∗46:01—as contributing to COVID-19 susceptibility. Conversely, HLA-B∗15:03 may offer some protection against the virus.22 Similarly, Linda Kachuri (Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco) and her colleagues have found a SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility signal in the EHF (ETS homologous factor) gene. The gene encodes a protein that acts as “an epithelial specific transcriptional repressor implicated in airway disease.”23

Pairing Network Medicine With ML

One of the most glaring shortcomings of the reductionistic approach is its application to clinical trials that evaluate individual treatment modalities. A study that measures the effect of increased zinc intake on viral infection, for instance, may result in a statistically insignificant finding because the nutrient’s benefits are synergistic with other nutrients or lifestyle modifications. When that is the case, it is not possible to detect any statistical or clinical significance unless all interventions are administered at the same time. If, for example, zinc repletion causes a 5% improvement in the complications of COVID-19, weight loss causes a 5% improvement, elimination of environmental allergens 5%, and so on, P values may not reach statistical significance for any one intervention unless the sample population is very large. It would be far more likely to reach statistical or clinical significance when all are implemented in unison.

With that in mind, employing ML-enhanced algorithms to analyze all the aforementioned risk factors and their interactions may help determine which ones predict a patient’s risk of COVID-19 or the prognosis of someone who has already tested positive. Of course, the challenge that remains is determining which variables to include in an ML analysis. The use of an unsupervised ML tool like clustering to analyze large data sets of COVID-19 patients may help detect suspected risk factors. Once these suspects are identified, random forest modeling may prove useful in evaluating their relative contribution to the infection. It has already been used to analyze a long list of interacting risk factors to determine whether they predict the development of cardiovascular complications among patients with type 2 diabetes.24 The same technique can be adapted to address multiple COVID-19 risk factors.

Baum et al demonstrated the value of random forest modeling by reexamining the results of a previous randomized clinical trial that had failed to demonstrate that an intensive lifestyle regimen of diet and exercise in overweight patients would reduce the rate of cardiovascular events or death.25 The Look AHEAD study assigned more than 5000 overweight and obese patients to the lifestyle regimen or to a control group that received only supportive education. The investigators’ goal was to determine whether the lifestyle program would reduce the incidence of death from cardiovascular disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for angina. The original plan was to observe these patients for as long as 13.5 years, but the study was terminated early because there were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups. The lower calorie content and increased exercise in the intensive lifestyle group did help patients lose weight, but it did not reduce the rate of cardiovascular events.

Baum et al employed random forest analysis to look at 84 separate risk factors or subgroups, creating a series of 1000 decision trees from all the available data. They used the stored characteristics of the 5000 patients in the Look AHEAD study and divided the cohort into halves. The first half served as a training data set to generate hypotheses and to construct the decision trees. The second half of the data served as the testing data set.

The 84 risk factors encompassed a long list of variables, including family history of diabetes, muscle cramps in legs and feet, history of emphysema, kidney disease, amputation, dry skin, loud snoring, marital status, social functioning, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level, self-reported health, and numerous other characteristics that researchers rarely consider when performing subgroup analysis. They identified covariates that were protective and deleterious. Baum et al discovered that intensive lifestyle modification averted cardiovascular events in two large subgroups, patients with HbA1c 6.8% or higher (poorly managed diabetes) and patients with well-controlled diabetes (HbA1c <6.8%) and good self-reported health. That finding applied to 85% of the entire population of patients studied. On the other hand, the remaining 15% who had controlled diabetes but poor self-reported general health responded negatively to the lifestyle modification regimen. The negative and positive responders cancelled each other out in the original statistical analysis conducted by the Look AHEAD investigators, which led them to falsely conclude that lifestyle modification was of no value.

A similar ML approach that incorporates all the known and suspected risk factors for COVID-19, including comorbidities and genetic, metabolic, and environmental variables, would allow us to identify cofactors that require attention. Such actionable insights will serve as the foundation for a holistic approach to the pandemic.

Using Artificial Intelligence to Inform Diagnosis, Phenotypes, and Pathogenesis

Random forest modeling is only one of many ML tools being adapted to manage COVID-19. Mayo Clinic researchers, in partnership with nference, an artificial intelligence (AI) technology company, have used a deep learning approach called nferX augmented curation26 to analyze the electronic health records of 15.8 million clinical notes from more than 30,000 patients who underwent COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction diagnostic testing. The analysis, which compared the clinical phenotypes of 29,859 COVID-19–negative patients with 635 positive patients, revealed distinct differences: COVID-19–positive patients were more than 37 times more likely to have experienced anosmia/dysgeusia. By contrast, they were only about twice as likely to have reported fever/chills, cough, or respiratory difficulty, demonstrating that loss of taste and loss of smell are better predictors of impending COVID-19 infection.

Xueyan Mei, with the BioMedical Engineering and Imaging Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, NY), and associates have used AI-enhanced algorithms that may improve the diagnosis of COVID-19. Using a convolutional neural network and multilayer perception classifiers, Mei et al27 integrated chest computed tomography findings suggestive of COVID-19 with clinical symptoms, exposure to the infection, and laboratory findings to enable clinicians to arrive at a diagnosis at an earlier stage of the disease. Mei et al concluded, “In a test set of 279 patients, the AI system achieved an area under the curve of 0.92 and had equal sensitivity as compared to a senior thoracic radiologist. The AI system also improved the detection of patients who were positive for COVID-19 via RT-PCR who presented with normal CT scans, correctly identifying 17 of 25 (68%) patients, whereas radiologists classified all of these patients as COVID-19 negative.”

A network medicine approach can also yield insights into the pathogenesis of COVID-19 through the use of proteomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and related -omics analysis. With the use of natural language processing, unstructured biomedical knowledge synthesis, and triangulation, Venkatakrishnan et al28 have evaluated more than 45 quadrillion links in unstructured biomedical text and used triangulation with single-cell RNA sequencing in more than 25 tissues to identify possible pathologic features of COVID-19 and the expression profile of the SAR-CoV-2 angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor. The analysis concluded that “tongue keratinocytes, airway club cells, and ciliated cells are likely underappreciated targets of SARS-CoV-2 infection, in addition to type II pneumocytes and olfactory epithelial cells. We further identify mature small intestinal enterocytes as a possible hotspot of COVID-19 fecal-oral transmission, where an intriguing maturation-correlated transcriptional signature is shared between ACE2 and the other coronavirus receptors DPP4 (MERS-CoV) and ANPEP (α-coronavirus).”

The available evidence suggests that we need to move beyond the traditional risk parameters and measures like vaccines, antiviral drugs, and personal protective gear and to see each patient as a whole person, subject to the many environmental, metabolic, and genetic variables that make us unique individuals. The interplay among all these cofactors has provided a new perspective on the pathogenesis of infectious disease and may open the door to innovative preventive and therapeutic options for COVID-19. Combining these insights with deep learning algorithms has the potential to completely redesign the way in which clinicians address the pandemic.

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ahn A.C., Tewari M., Poon C.S., Phillips R.S. The limits of reductionism in medicine: could systems biology offer an alternative? PLoS Med. 2006;3(6):e208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loscalzo J., Barabasi A.L., Silverman E.K. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2017. Network Medicine: Complex Systems in Human Disease and Therapeutics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019: situation summary November 14, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/summary.html#:∼:text=COVID%2D19%20is%20caused,CoV%2D2 Accessed November 21, 2020.

- 4.Heneghan C., Brassey J., Jefferson T. COVID-19: what proportion are asymptomatic? The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. April 6, 2020. https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/covid-19-what-proportion-are-asymptomatic/ Accessed November 21, 2020.

- 5.World Health Organization Q and A on coronaviruses (COVID-19). April 17, 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses Accessed September 3, 2020.

- 6.Johns Hopkins University and Medicine Mortality in the most affected countries. Coronavirus Resource Center, May 25, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality Accessed September 3, 2020.

- 7.Ahn A.C., Tewari M., Poon C.S., Phillips R.S. The clinical applications of a systems approach. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg S., Kim L., Whitaker M., et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simonnet A., Chetboun M., Poissy J., et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical 3ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28(7):1195–1199. doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention People with certain medical conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html Accessed September 3, 2020.

- 11.Alipio M. Vitamin D supplementation could possibly improve clinical outcomes of patients infected with coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19). April 9, 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3571484 Accessed September 3, 2020.

- 12.Martineua A.R., Jolliffe D.A., Hooper R.L., et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daneshkhah A., Agrawal V., Eshein A., Subramanian H., Roy H.K., Backman H. The possible role of vitamin D in suppressing cytokine storm and associated mortality in COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. Accessed September 20, 2020. [DOI]

- 14.Wessels I., Maywald M., Rink L. Zinc as a gatekeeper of immune function. Nutrients. 2017;9(12):1286. doi: 10.3390/nu9121286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Read S.A., Obeid S., Ahlenstiel C., Ahlenstiel G. The role of zinc in antiviral immunity. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(4):696–710. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pazirandeh S., Burns D.L., Griffin I.J. Overview of dietary trace elements. UpToDate. March 20, 2020. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-dietary-trace-elements?search=zinc%20deficiency§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H58&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=2∼103&display_rank=2#H58 Accessed September 3, 2020.

- 17.National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements Zinc. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Zinc-HealthProfessional/

- 18.Willis M.S., Monaghen S.A., Miller M.L., et al. Zinc-induced copper deficiency: a report of three cases initially recognized on bone marrow examination. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123(1):125–131. doi: 10.1309/v6gvyw2qtyd5c5pj. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaser R., Kiecolt-Glaser J.K. Stress-induced immune dysfunction. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(3):243–251. doi: 10.1038/nri1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fondell E., Lagerros Y., Sundberg C., et al. Physical activity, stress, and self-reported upper respiratory tract infection. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(2):272–279. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181edf108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews C., Ockene I.S., Freedson P., Rosal M.C., Merriam P.A., Hebert J.R. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and risk of upper-respiratory tract infection. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(8):1242–1248. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen A., David J.K., Maden S.K., et al. Human leukocyte antigen susceptibility map for SARS-CoV-2. J Virol. 2020;94(13):e00510–e00520. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00510-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kachuri L., Francis S.S., Morrison M., et al. The landscape of host genetic factors involved in infection to common viruses and SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. June 1, 2020. Accessed November 21, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Baum A., Scarpa J., Bruzelius E., Tamler R., Basu S., Faghmous J. Targeting weight loss interventions to reduce cardiovascular complications of type 2 diabetes: a machine learning-based post-hoc analysis of heterogeneous treatment effects in the Look AHEAD trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(10):808–815. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30176-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Look AHEAD Research Group Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shweta F., Murugadoss K., Awasthi S., et al. Augmented curation of unstructured clinical notes from a massive EHR system reveals specific phenotypic signature of impending COVID-19 diagnosis. medRxiv. April 30, 2020. Accessed November 21, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Mei X., Lee H.C., Diao K.Y., et al. Artificial intelligence–enabled rapid diagnosis of patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1224–1228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0931-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venkatakrishnan A.J., Puranik A., Anand A., et al. Knowledge synthesis from 100 million biomedical documents augments the deep expression profiling of coronavirus receptors. bioRxiv. March 29, 2020. Accessed November 21, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]