Abstract

An extension of the classical pandemic SIRD model is considered for the regional spread of COVID-19 in France under lockdown strategies. This compartment model divides the infected and the recovered individuals into undetected and detected compartments respectively. By fitting the extended model to the real detected data during the lockdown, an optimization algorithm is used to derive the optimal parameters, the initial condition and the epidemics start date of regions in France. Considering all the age classes together, a network model of the pandemic transport between regions in France is presented on the basis of the regional extended model and is simulated to reveal the transport effect of COVID-19 pandemic after lockdown. Using the measured values of displacement of people between cities, the pandemic network of all cities in France is simulated by using the same model and method as the pandemic network of regions. Finally, a discussion on an integro-differential equation is given and a new model for the network pandemic model of each age class is provided.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic model, Optimization, Network model

1. Introduction

Up to now, COVID-19 has widely spread over the world and is much more contagious than expected. The outbreak of COVID-19 has resulted in a huge pressure of hospital capacity and a massive death of population in the world. Quarantine and lockdown measures have been taken in many countries to control the spread of the infection, and has proved the amazingly effectiveness of these measures for the outbreak of COVID-19, in particular in China (see Kucharski et al. (2020)). Quarantine is a rather old technique to prevent the spread of diseases. It is used at the individual level to constrain the movement of all the population and encourage them stay at home. Lockdown measures reduce the pandemic transmission by increasing social distance and limiting the contacts and mobility of people, e.g. with cancellation of public gatherings, the closure of public transportation, the closure of borders. COVID-19 may yield a very large number of asymptomatic infected individuals, as mentioned in Al-Tawfiq (2020) and Day (2020). Therefore, most countries have implemented indiscriminate lockdown. But the long time of duration of lockdown can cause inestimable financial costs, many job losses, and particularly psychological panic of people and social instability of some countries.

As declared by some governments (see Gostic, Gomez, Mummah, Kucharski, & Lloyd-Smith (2020)), testing is crucial to exit lockdown, mitigate the health harm and decrease the economic expensation. In this paper, we consider two classes of active detection. The first one is the short range test: molecular or Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test, that is used to detect whether one person has been infected in the past. The second test is the long range test: serology or immunity test, that allows to determine whether one person is immune to COVID-19 now. This test is used to identify the individuals that cannot be infected again.

For our research on COVID-19, we aim to evaluate the effect of lockdown within a given geographical scale in France, such as the largest cities, or urban agglomerations, or French departments, or one of the 13 Metropolitan Regions (to go from the finest geographical scale to the largest one). The estimations of effect are also considered on different age-classes, such as early childhood, scholar childhood, working class groups, or the elderly. Besides, we propose to understand the effect of partial lockdown or other confinement strategies depending on some geographical perimeters or some age groups (as the one that Lyon experienced very recently, see FranceTvInfo (2020))

In the context of COVID-19, there have been many papers that focus on estimating the effect of lockdown strategies on the spread of the pandemic (e.g. Berger, Herkenhoff, and Mongey (2020) and Roques, Klein, Papaix, Sar, and Soubeyrand (2020)). In Prague et al. (2020), the lockdown effect is estimated using stochastic approximation, expectation maximization and an estimation of basic reproductive numbers. In this work, we aim at evaluating the dynamics of the pandemic after the lockdown by looking on the transport effect.

In this paper, one contribution is that an extension of the typical SIRD pandemic model is presented for characterizing the regional spread of COVID-19 in France before and after the lockdown strategies. Taking into account the detection ratios of infected and immune persons, this extended compartment model integrates all the related features of the transmission of COVID-19 in the regional level. In order to estimate the effect of lockdown strategies and understand the evolution of the undetected compartments for each region in France, an optimization algorithm is used to derive the optimal parameters for regions by fitting the extended model to real reported data during the lockdown.

Based on regional model analysis before and after the lockdown, we present a network model to characterize the pandemic transmission between regions in France after lockdown and evaluate the transport effect of COVID-19 pandemic, when considering all age classes together. The most interesting point is the chosen exponential transmission rate (time-dependent) function β, in order to incorporate the complex effect of lockdown and unlockdown strategies.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the extended model is derived from the classical pandemic SIRD model and the rationale behind the model is explained. In Section 3, we present the parameters optimization problem and estimate the effect of lockdown strategies. From the calibration of parameters for each region in France, we derive the pandemic start date of regions. Network model of pandemic transmission between regions is introduced and the network simulation is implemented in Section 4. In Section 5, using the same model as the pandemic network of regions in France, we simulate the pandemic network of all cities in France. In the ’Discussion’ section, considering the age classification, an integro-differential model is presented for the pandemic network transmission, at any geographical scale, and for any set of age classes.

2. Pandemic Model

In this paper, the scenario we consider is a large safe population into which a low level of infectious agents is introduced and a closed population with neither birth, nor natural death, nor migration. There is one basic model of modelling pandemic transmission which is well known as susceptible-infected-recovered-dead (SIRD) model in Brauer and Castillo-Chavez (2012). This mathematical compartmental model is described as follows,

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where S(t) is the number of susceptible people at time t, I(t) is the number of infected people at time t, R(t) is the number of recovered people at time t, D(t) is the number of deaths due to pandemic until time t, with constant parameters: β is transmission rate per infected, δ is the removal or recovery rate, α is the disease mortality rate. The compartment variables S(t), I(t), R(t), D(t) satisfy

| (5) |

at any time instant t, here N is the total number of population of the considered area.

From the differential equations (1)-(4), it is obvious that at any time instant t, the total rate βI(t) of transmission from entire susceptible compartment to infected compartment is proportional to the infected I; the infected individuals recover at a constant rate δ; the infected go to death compartment at a constant rate α.

In fact, with the exception of the detected well-known data, there are some undetected data that cannot be measured but are significantly important for the analysis of the evolution of COVID-19 in France under lockdown policy. Moreover they are useful to provide efficient social policies, such as optimal management of limited healthcare resources, the ideal decision of the duration and level of lockdown or re-lockdown, and so on.

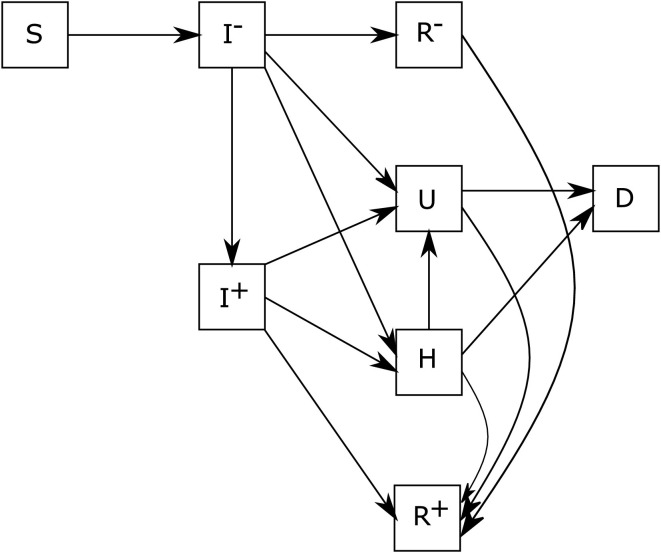

Inspired by Charpentier, Elie, Laurière, and Tran (2020), the basic SIRD model is extended to a more sophisticated compartmental model which includes several features of the recent COVID-19 outbreak, with flexibility with respect to lockdown and test strategies. More sophisticated models could be considered, however it is important that the model we consider can be calibrated with the available data for French regions. On the basis of model in Charpentier, Elie, Laurière, and Tran (2020), this model additionally considers that the infected undetected individuals and the infected detected individuals get sicker and then go to intensive care U, and the hospitalized individuals H die (D) before attaining intensive care U. In our model, the short term tests transfer the positive individuals from compartment to compartment . The detection using antibody tests allows to transfer individuals from compartment to compartment . The presence of antibodies indicate that one person has recovered from the pandemic and is immune. The flow diagram of this model is sketched out in Figure 1 .

Fig. 1.

The evolution of each compartment is modelled by the following equations,

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

with

| (14) |

and initial conditions

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

where S(t) is the number of susceptible individuals at time t, is the number of infected undetected individuals at time t, is the number of infected detected individuals at time t, is the number of recovered undetected individuals at time t, is the number of recovered detected individuals at time t, H(t) is the number of hospitalized individuals at time t, U(t) is the number of individuals hospitalized in an intensive care unit at time t, D(t) is the cumulative number of dead individuals from hospital or intensive care at time t.

During the incubation period (time taken from infection to symptom exhibition) but after the latent period (time taken from infection to infectiousness), this is the so-called exposed period, the infected individuals can transmit the epidemic without any symptom. Unfortunately we don't have any data on the exposed population, making hard to identify the number of infected individuals. Therefore we incorporate this class of infected individuals into the undetected infected compartment .

The number of exposed individuals who travel internationally is neglected in this paper, since (at the time of the writing) only a few people travel internationally. We do not consider here deaths from nursing homes for example, as in Veiga, Gamboa, Iooss, and Prieur (2020, Chapter 6), where a slightly different is considered at the French national scale. The main reason for that is the lack of data. Indeed, daily data on the total reported cases are unavailable in France at the regional scale. The initial conditions (15)-(17) mean that infected people are introduced into a population consisting of susceptible individuals at time instant . Both and are two unknown parameters that need to be identified.

Two types of tests are taken into account in this model, one is a class of virological tests like nasal ones that can detect new infectious cases from compartment . The rate of these tests is denoted by ; another method is a class of serological tests that detect the individuals of infected and sequentially recovered from compartment applying blood or saliva samples, the rate of these tests (for example, blood test) is denoted by . This second type of tests was not proposed in France until very recently, thus we consider in this work that .

Remark 1

With respect to the second type test, it is an antibody test which uses serological immunoassays to detect viral-specific antibodies: Immunoglobin M (IgM) and G (IgG). The antibodies IgM that suggests infection have a half-life of around five days, and they usually appear within five to seven days of infection and peak at around 21 days. The antibodies IgG that indicates recovery and immunity can be detected around 10 to 14 days after infection. The immunity test allows to verify if one person is immune to the epidemic. The identified immune person could obtain an immunity certificate to have normal social activities, and then be allowed to travel between regions thus impacting our model. Consequently, the level of social interactions is raised and then social economy is recovered.

The other parameters in equation (6)-(13) are defined as follows:

-

•

is the daily individual transition rate from I to R, and

-

•

is the daily individual transition rate from I to H, and

-

•

is the daily individual transition rate from I to U, and

-

•

is the daily individual transition rate from H to R, and

-

•

is the daily individual transition rate from H to D, and

-

•

is the daily individual transition rate from H to U, and

-

•

is the daily individual transition rate from U to R, and

-

•

is the daily individual transition rate from U to D, and

with

-

•

: the probability of having light symptoms or no symptoms for the infected individuals; : the probability of needing hospitalization for mild or severely ill people; : the probability of needing intensive care for mild or severely ill people; : the probability of needing intensive care under hospitalization without intensive care; : the probability of death under hospitalization without intensive care; : the probability of death under intensive care;

-

•

: the number of days it takes for an asymptomatic case needs to recover; : the number of days it takes for a symptomatic case to recover without hospitalization; : the number of days a severely symptomatic case requires until hospitalization; : the number of days before death in the event of hospitalization; : the number of days required for a hospitalized case until intensive care is provided; : the number of days before death in the event of intensive care; : the number of days it takes for a hospitalized case to recover; : the number of days it takes for a case under intensive care to recover.

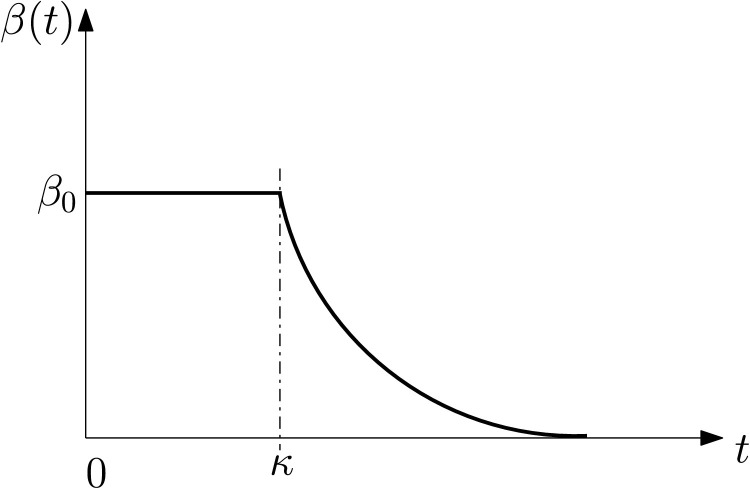

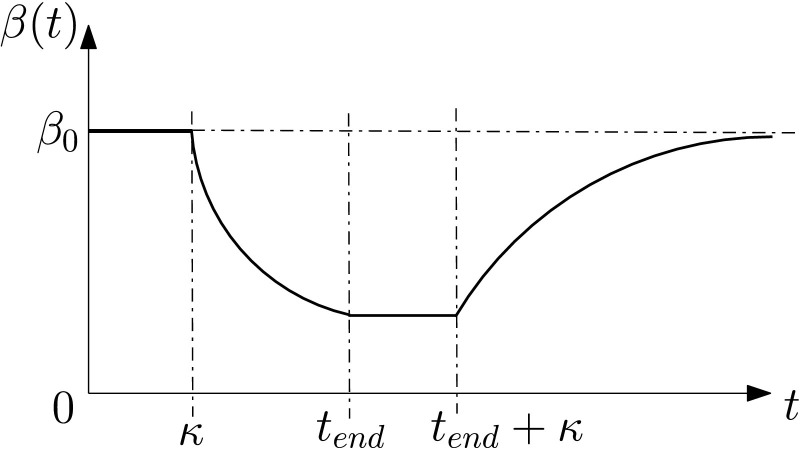

The infection transmission rate β(t) is the rate of the pandemic transmission from an undetected infected person to susceptible individuals at time instant t. As in Magal and Webb, in order to combine the complex effects of lockdown strategy, a time-dependent exponentially decreasing function can be used to model the transmission rate β(t),

| (18) |

with constant parameters β 0, μ and κ. Note that β(t) is constant during the initial stage of implementing effective lockdown strategies such as social distance, quarantine, healthcare, and mask worn. The transmission rate exponentially decreases at rate μ after these lockdown strategies take effect. The transmission rate β(t) can be illustrated in Figure 2 .

Fig. 2.

Time-evolution of the transmission rate β before and during the lockdown.

As one of the most critical epidemiological parameters, the basic reproductive ratio defines the average number of secondary cases an average primary case produces in a totally susceptible population (see Keeling & Rohani (2008)). As for the model in Charpentier, Elie, Laurière, and Tran (2020), for the considered model in this paper, only the individuals transmit the disease to the susceptible individuals during the early phase of outbreak. If < 1 (i.e., ), the infection ”dies out” over time; inversely, if > 1 (i.e., ), the initial number of susceptible individuals exceeds the critical threshold to allow the pandemic to spread. Thus the initial basic reproductive rate is

| (19) |

When the transmission rate β(t) and the number of susceptible people S(t) evolve as time goes by, one dynamic reproductive rate that depends on time is introduced and known as effective reproduction number R(t) in Tillett (1992). In this model, it is defined as, for t ≥ 0,

| (20) |

Similarly, when R(t) < 1, the number of secondary cases infected by a primary undetected infected case on day t, dies out over time, leading to a delay in the number of infected individuals. But when R(t) > 1, the number of undetected infected individuals grows over time. Therefore, by the control of the transmission rate β(t) that can constrain R(t) to be less than 1, the number of infected individuals grows slowly to ease the pressure on medical resources. When S(t) is bellow a threshold, the epidemic goes to extinction (see e.g., Pardoux & Britton (2019)). The required level of vaccination to eradicate the infection is also attained from the effective reproduction number.

The compartmental model introduced in Figure 1 exhibits a large number of unknown parameters (20 if we consider ). The uncertainty on these parameters can not be neglected. As an example, until the end of this section, let us propagate uncertainty at the scale of the region Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. The vector of unknown parameters is:

| (21) |

We take into account the uncertainties on these parameters by considering that each parameter is uniformly distributed with bounds consistent with typical reported values (see, e.g., Charpentier, Elie, Laurière, and Tran (2020) and references therein). Lower and upper bounds for each parameter are reported in Table 1 hereafter.

Table 1.

Uncertainty bounds for all model parameters.

| parameters | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower bounds | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 15 | 8 |

| upper bounds | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | 12 | 15 | 12 | 20 | 12 |

| parameters | μ | κ | ||||||||

| lower bounds | 15 | 15 | 2.5 | 2020-02-06 | 0.03 | 20 | 1e-4 | 0.001 | 1 | 1 |

| upper bounds | 25 | 20 | 4.5 | 2020-02-12 | 0.1 | 50 | 1e-3 | 0.01 | 10 | 100 |

The parameter sampling approach is based on the generation of a low-discrepancy sequence of 5000 points on the unit hypercube [0, 1]20. Low-discrepancy sequences have the property of uniformly and regularly filling the unit hypercube, without the clustering issues encountered by Monte Carlo samples. Sobol’ sequences (see Sobol’ (1967)) are among the best low-discrepancy sequences with solid theoretical properties and good numerical performance when dimension increases.

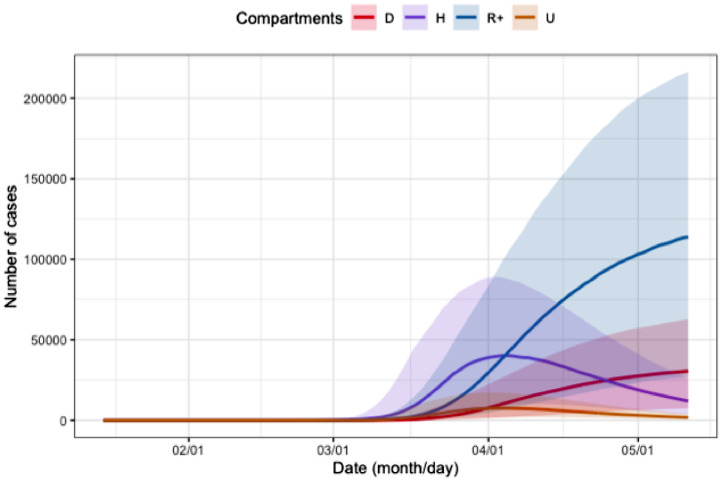

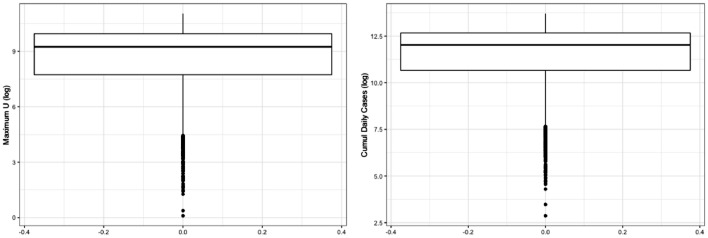

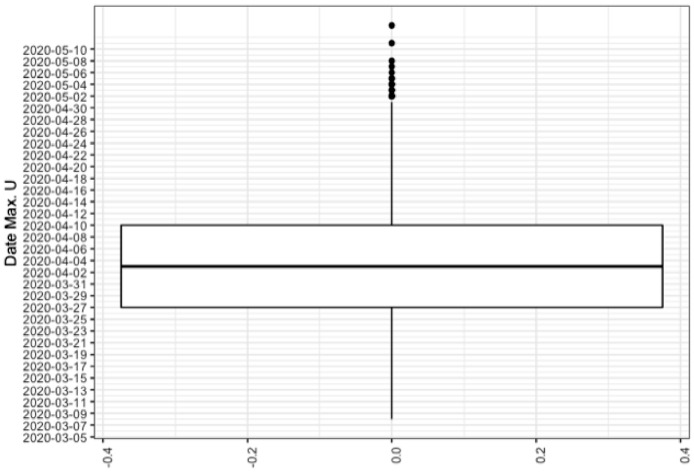

Figure 3 shows that the prior uncertainty is pretty high, since for example the difference between the 75% and the 25% quantiles for the number of people in hospital is more than 50000 at the end of the lockdown period. On Figures 4 and 5 we propagate the parameter uncertainty on the maximum number of people in intensive care units, on the date at which this maximum value is attained and on the total number of reported cases. Note that the total number of reported cases is obtained from the daily number of reported cases, DR, which is driven by the following equation:

The maximum number of people in intensive care is particularly important as it provides information on the capacities the intensive care units should have to face the sanitary crisis. We show for each of these three scalar quantities of interest the boxplot which visualises five summary statistics (the median, two hinges and two whiskers) and all outlying points individually. The lower and upper hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles (the 25th and 75th percentiles). The upper whisker extends from the hinge to the largest value no further than 1.5 * IQR from the hinge (where IQR is the inter-quartile range, or distance between the first and third quartiles). The lower whisker extends from the hinge to the smallest value at most 1.5 * IQR of the hinge. Data beyond the end of the whiskers are called ”outlying” points and are plotted individually. We see for example on these boxplots that the median for the maximum number of people in intensive care is more than 8000 with the IQR greater than 20000.

Fig. 3.

Prior uncertainty quantification for compartments D (in red), H (in purple), (in blue) and U (in orange) for the region Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. The bold lines are the pointwise medians of each functional output, whereas the colored surface is the range between the pointwise first and third quartiles.

Fig. 4.

Prior uncertainty quantification for maximum value of U (left), and total number of reported cases (right) for the region Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes.

Fig. 5.

Prior uncertainty quantification for the day where maximum value of U is reached for the region Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes.

In view of the importance of uncertainties propagated from the model parameters to the quantities of interest (e.g., number of infected people at hospitals), it appears necessary to calibrate the model. Our calibration procedure is described in the next section.

3. Parameter identification

In this section, regional scales of France are considered and all age classes are summed to calibrate the parameters of the pandemic model (6)-(13) during confinement on the basis of data about the pandemic in France. Since all regions are not connected during the lockdown, it is sufficient to identify separtely all unknown parameters for each region. From the calibration of the model, we can observe the effects of lockdown strategies on the unknown variables, in particular for infected undetected population and recovered undetected population. The following weighted least square cost function is minimized for parameters optimization:

where p is a vector which consists of calibrated parameters; Zmeas(ti) is the measured values of the corresponding observed state vector Z(p, ti) at time ti, with n the number of days considered for calibration. This optimization problem is solved using Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (see Moré (1978)). Since it is a local algorithm, we adopt, as in (Veiga et al., 2020, Chapter 6), a multi-start approach where the initial values are obtained from a Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS). LHS was introduced in McKay, Beckman, and Conover (2000) as space-filling designs on the unit hypercube. The LHS is built on the unit hypercube [0, 1]20 and then rescaled with the upper and lower bounds given in Table 1. The unknown parameter vector p defined in (21) is calibrated on daily data for H, U, D and on the lockdown period 2020-03-18 to 2020-05-11, for each region, from two data sources: the first one is a public and governmental data source (Gouvernement français, 2020) and the second one is a dedicated national platform with a privileged access (Ministère des solidarités et de la santé, 2020).

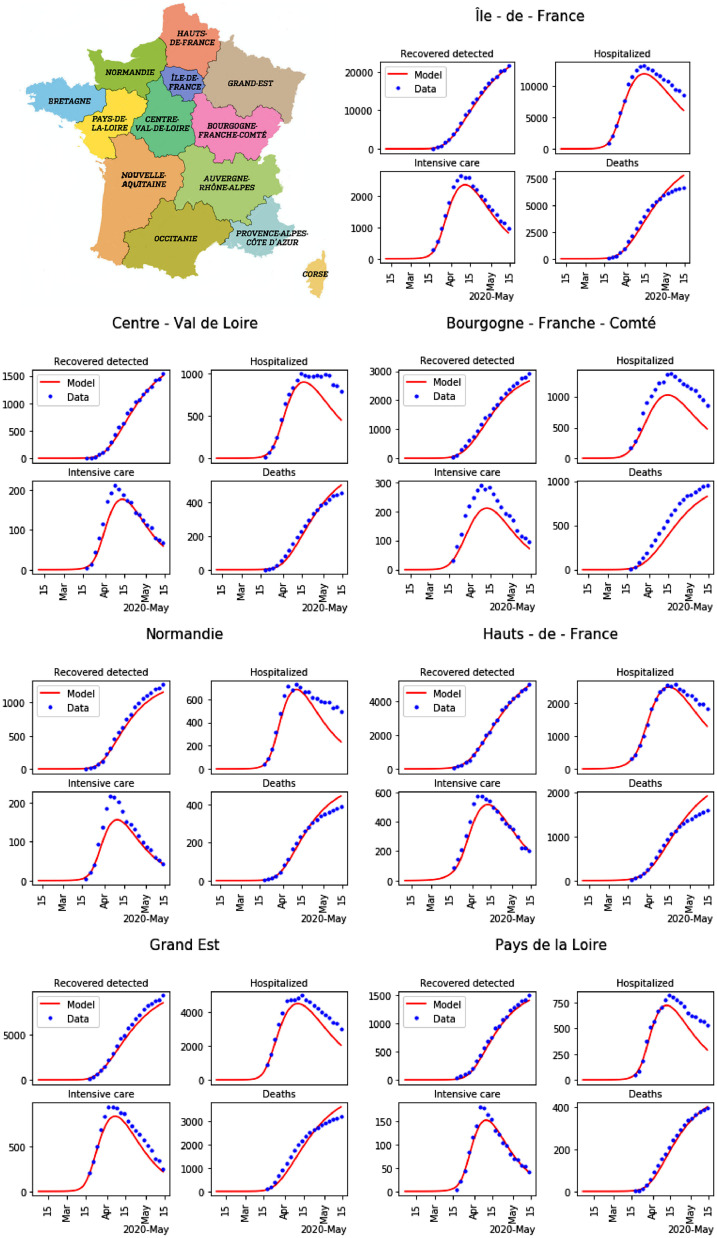

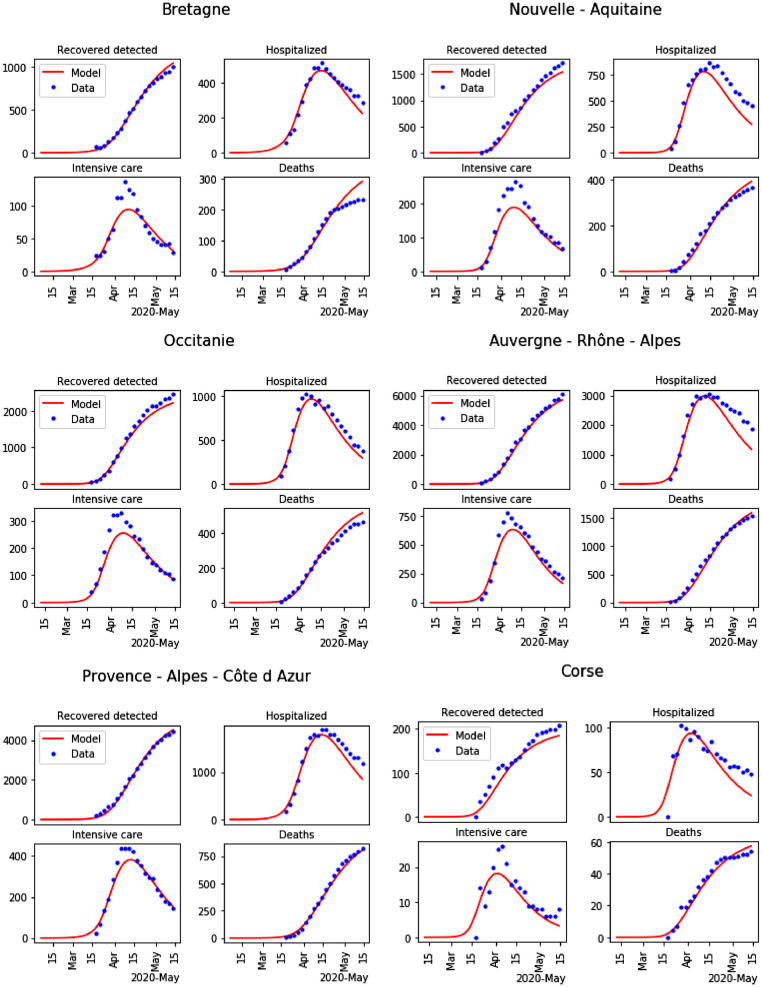

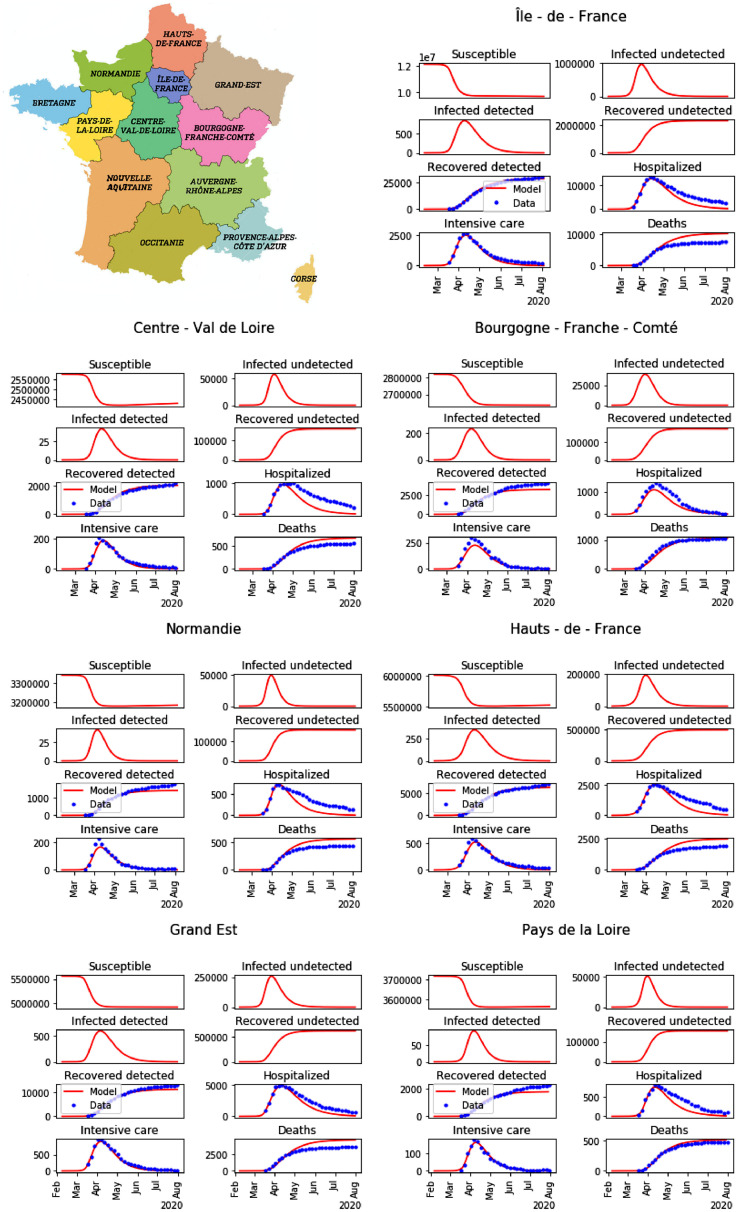

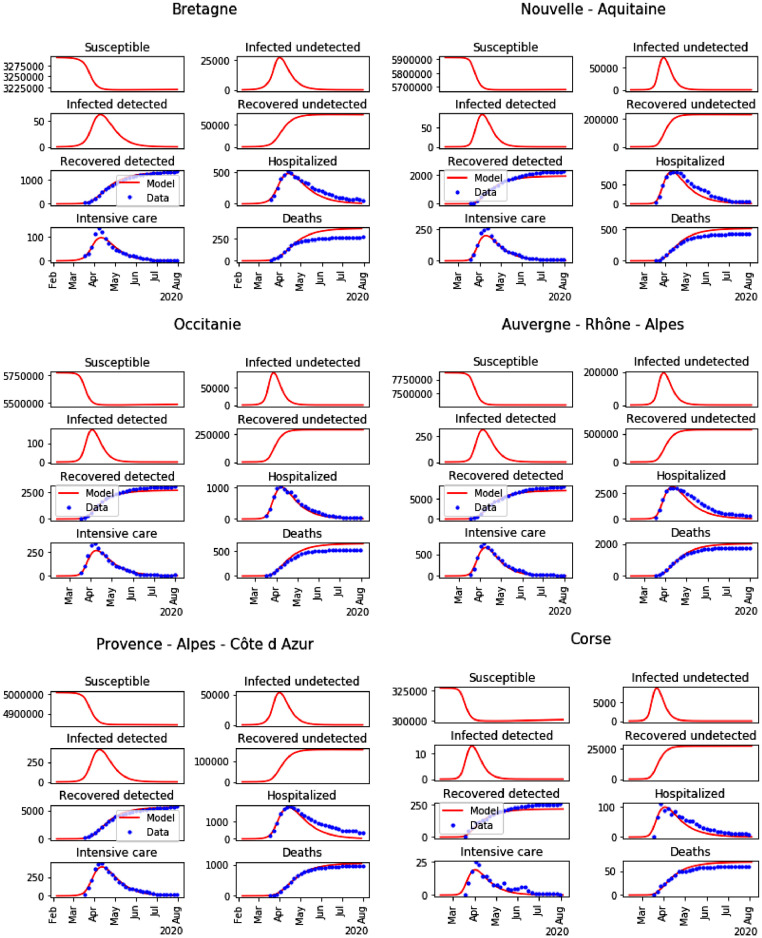

The time step is chosen as ten percentage of one day for the numerical discretization. A general solver for ordinary differential equations is used to compute H, U, D or for each region for all time until the end of lockdown. The results of the calibration are given in Tables 2 to 5 . The results of parameter calibration for the 13 regions in France are shown in Figures 6 and 7 .

Table 3.

Optimal values of parameters for each region.

| Regions \ Parameters | μ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Île-de-France | 12.0 | 20.0 | 9.724 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 0.10 |

| Centre-Val de Loire | 12.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 15.0 | 0.1 |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 12.0 | 20.0 | 8.391 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 0.043 |

| Normandie | 12.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 23.027 | 20.0 | 0.1 |

| Hauts-de-France | 12.0 | 20.0 | 9.303 | 24.331 | 20.0 | 0.1 |

| Grand Est | 11.221 | 20.0 | 8.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 0.0997 |

| Pays de la Loire | 12.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 0.1 |

| Bretagne | 12.0 | 15.225 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 15.096 | 0.1 |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 12.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 0.1 |

| Occitanie | 12.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 0.1 |

| Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 12.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 25.00 | 20.0 | 0.1 |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur | 8.867 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 0.084 |

| Corse | 12.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 0.1 |

Table 4.

Optimal values of parameters κ,, , for each region.

| Regions \ Parameters | κ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Île-de-France | 35.759 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 3.071 |

| Centre-Val de Loire | 40.141 | 0.0001 | 0.01 | 10.0 |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 25.360 | 0.001 | 0.00291 | 1.564 |

| Normandie | 37.718 | 0.000152 | 0.01 | 10.0 |

| Hauts-de-France | 40.928 | 0.000193 | 0.01 | 10.0 |

| Grand Est | 33.745 | 0.000261 | 0.0011 | 4.588 |

| Pays de la Loire | 43.524 | 0.000296 | 0.001 | 8.917 |

| Bretagne | 44.838 | 0.000259 | 0.01 | 10.0 |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 36.702 | 0.000194 | 0.0064 | 2.277 |

| Occitanie | 36.056 | 0.000330 | 0.01 | 2.094 |

| Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 37.142 | 0.000247 | 0.001 | 3.238 |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur | 42.813 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 10.0 |

| Corse | 29.198 | 0.000271 | 0.01 | 10.0 |

Table 2.

Optimal values of parameters for each region.

| Regions \ Parameters | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Île-de-France | 0.9 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.20 | 0.3 | 12.0 | 13.104 |

| Centre-Val de Loire | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.21 | 0.3 | 9.674 | 8.0 |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 0.83 | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | 6.423 | 8.576 |

| Normandie | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | 6.527 | 15.0 |

| Hauts-de-France | 0.9 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.244 | 0.3 | 12.0 | 15.0 |

| Grand Est | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | 12.0 | 14.551 |

| Pays de la Loire | 0.9 | 0.189 | 0.2 | 0.193 | 0.3 | 7.608 | 9.191 |

| Bretagne | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.151 | 0.3 | 12.0 | 8.153 |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 0.9 | 0.150 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 6.883 | 15.0 |

| Occitanie | 0.9 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 6.803 | 9.767 |

| Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.176 | 0.3 | 7.820 | 15.0 |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur | 0.852 | 0.192 | 0.192 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 9.446 | 15.0 |

| Corse | 0.9 | 0.15 | 0.179 | 0.222 | 0.3 | 6.433 | 13.62 |

Table 5.

Optimal values of initial conditions start time of infection and basic reproduction rate .

| Regions \ Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Île-de-France | 30.454 | 2020-02-11 | 4.120 |

| Centre-Val de Loire | 1.025 | 2020-02-11 | 3.347 |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 1.0 | 2020-02-11 | 3.008 |

| Normandie | 1.131 | 2020-02-12 | 2.774 |

| Hauts-de-France | 200.0 | 2020-02-10 | 2.883 |

| Grand Est | 3.508 | 2020-02-08 | 4.5 |

| Pays de la Loire | 1.022 | 2020-02-06 | 2.772 |

| Bretagne | 50.582 | 2020-02-06 | 2.5 |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 1.282 | 2020-02-11 | 2.950 |

| Occitanie | 14.708 | 2020-02-12 | 2.548 |

| Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 15.620 | 2020-02-11 | 2.884 |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur | 25.299 | 2020-02-06 | 2.583 |

| Corse | 1.0 | 2020-02-12 | 2.859 |

Fig. 6.

Minimap of regions in France, and result of the parameters calibration for the first 7 regions among 13 (blue dots: data, and red lines: model).

Fig. 7.

Result of the parameters calibration for the last 6 regions among 13 (blue dots: data, and red lines: model).

4. Network simulation

In order to characterize the dynamics of the pandemic transmission processes during the confinement, the epidemiological model (6)-(13) was described in the previous section. We now consider the government action of unlockdown after confinement, there is a pandemic transmission effect between each region in France. The following pandemic network model of N regions is introduced, for

| (22) |

| (23) |

| (24) |

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

where

-

•

the transmission rate t↦βi(t) of region i is a continuous function depending on the scenario (lockdown or no-lockdown), depending on the time t;

-

•

Lik is the number of individuals moving from region i to region k in a given time length Tik depending on the pair (i, k);

-

•

the function σ(i, k, t) is a weighting function that determines the mobility betweenregion i and region k at time t. It is assumed to be time-periodic with the period Tik, satisfies and takes values in the interval ;

-

•

Nk is the population of region k; the other parameters ... depend on the location i;

-

•

Ci is the set of all regions that have pandemic transmission with region i.

As the fast periodic switching policy in Bin et al. (2020), we consider the inverse of the (same) exponential function of infection transmission rate β(t) in (18) to denote βi(t). Even though the end of confinement, the social strategies still go on, so a continuous function β(t) is used for the whole transmission process of COVID-19 from the start date of infection,

| (30) |

with the end time of lockdown tend.

The transmission rate β(t) for the whole transmission process is illustrated in Figure 8 .

Fig. 8.

The transmission rate β(t) for the network model.

For the mobility analysis after lockdown, we compute the mobility matrix using data of the displacement of population in France as measured by the Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE). To be more specific, the professional displacements and the scholar displacements are given for each French city in INSEE (2020) for some age classes. This information allows us to compute, for each as the fraction of people (with respect to the total population in region k) travelling from region k to region i. For the numerical simulation, we assume that the mobility matrix is computed for a time length of one day (that is day) for any pair of regions (i, k). The components of the matrix are shown in Tables 6 ,7 ,8 .

Table 6.

First part of components of the mobility matrix .

| Region k \ Region i | Île-de-France | Centre-Val de Loire | Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | Normandie |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Île-de-France | 0.000e+00 | 3.662e-04 | 1.870e-04 | 3.828e-04 |

| Centre-Val de Loire | 5.485e-03 | 0.000e+00 | 8.279e-04 | 5.642e-04 |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 1.136e-03 | 4.346e-04 | 0.000e+00 | 5.651e-05 |

| Normandie | 2.803e-03 | 6.993e-04 | 5.574e-05 | 0.000e+00 |

| Hauts-de-France | 4.077e-03 | 6.803e-05 | 8.013e-05 | 5.169e-04 |

| Grand Est | 7.146e-04 | 5.116e-05 | 5.833e-04 | 6.038e-05 |

| Pays de la Loire | 7.411e-04 | 6.476e-04 | 5.488e-05 | 8.895e-04 |

| Bretagne | 6.099e-04 | 1.103e-04 | 4.689e-05 | 4.358e-04 |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 6.153e-04 | 3.345e-04 | 6.910e-05 | 7.362e-05 |

| Occitanie | 4.616e-04 | 5.165e-05 | 7.992e-05 | 5.219e-05 |

| Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 4.855e-04 | 1.066e-04 | 8.104e-04 | 5.503e-05 |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur | 5.062e-04 | 4.511e-05 | 8.287e-05 | 5.736e-05 |

| Corse | 8.718e-04 | 1.388e-04 | 1.388e-04 | 9.041e-05 |

Table 7.

Second part of components of the mobility matrix .

| Region k \ Region i | Hauts-de-France | Grand Est | Pays de la Loire | Bretagne | Nouvelle-Aquitaine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Île-de-France | 7.848e-04 | 3.485e-04 | 2.200e-04 | 1.412e-04 | 2.667e-04 |

| Centre-Val de Loire | 1.475e-04 | 1.452e-04 | 7.035e-04 | 1.668e-04 | 7.710e-04 |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 1.020e-04 | 1.203e-03 | 6.397e-05 | 5.295e-05 | 1.091e-04 |

| Normandie | 8.391e-04 | 1.043e-04 | 6.113e-04 | 4.062e-04 | 1.193e-04 |

| Hauts-de-France | 0.000e+00 | 6.536e-04 | 6.719e-05 | 7.274e-05 | 8.853e-05 |

| Grand Est | 3.738e-04 | 0.000e+00 | 7.719e-05 | 7.086e-05 | 8.116e-05 |

| Pays de la Loire | 1.112e-04 | 8.988e-05 | 0.000e+00 | 1.470e-03 | 1.013e-03 |

| Bretagne | 1.175e-04 | 9.190e-05 | 1.661e-03 | 0.000e+00 | 1.835e-04 |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 1.229e-04 | 8.998e-05 | 6.295e-04 | 9.172e-05 | 0.000e+00 |

| Occitanie | 1.169e-04 | 9.261e-05 | 7.412e-05 | 6.760e-05 | 1.044e-03 |

| Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 1.262e-04 | 1.512e-04 | 6.770e-05 | 6.426e-05 | 2.210e-04 |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur | 1.212e-04 | 1.117e-04 | 5.164e-05 | 6.124e-05 | 1.312e-04 |

| Corse | 1.970e-04 | 1.647e-04 | 6.781e-05 | 1.292e-04 | 4.036e-04 |

Table 8.

Third part of components of the mobility matrix .

| Region k \ Region i | Occitanie | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur | Corse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Île-de-France | 2.133e-04 | 3.019e-04 | 1.429e-04 | 1.001e-05 |

| Centre-Val de Loire | 1.209e-04 | 3.582e-04 | 6.160e-05 | 2.747e-06 |

| Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 1.009e-04 | 1.918e-03 | 1.084e-04 | 3.198e-06 |

| Normandie | 8.647e-05 | 1.681e-04 | 6.719e-05 | 2.712e-06 |

| Hauts-de-France | 8.618e-05 | 1.409e-04 | 5.090e-05 | 1.008e-06 |

| Grand Est | 7.556e-05 | 1.791e-04 | 1.106e-04 | 1.808e-06 |

| Pays de la Loire | 9.884e-05 | 2.159e-04 | 5.404e-05 | 2.520e-06 |

| Bretagne | 1.097e-04 | 1.638e-04 | 6.189e-05 | 6.252e-06 |

| Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 9.997e-04 | 3.356e-04 | 9.190e-05 | 4.873e-06 |

| Occitanie | 0.000e+00 | 6.060e-04 | 1.626e-03 | 7.430e-06 |

| Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 3.787e-04 | 0.000e+00 | 4.293e-04 | 6.202e-06 |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur | 1.115e-03 | 8.193e-04 | 0.000e+00 | 2.613e-05 |

| Corse | 5.199e-04 | 3.487e-04 | 1.698e-03 | 0.000e+00 |

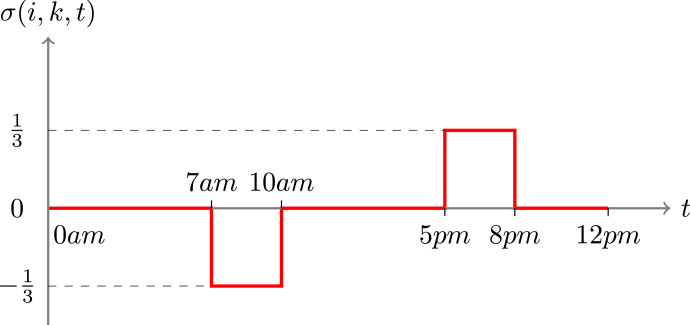

For the numerical simulation, we choose 1 hour as the time step. As far as the function σ is concerned, for any regions i and k, σ(i, k, t) is constant and negative between time 7am and 10am and is constant and positive between 5pm and 8pm, zero otherwise and satisfies . See Figure 9 for the discretized version of the function t↦σ(i, k, t). Physically, it corresponds to a constant traffic of people in the morning from region i to region k and a constant traffic of people back in the afternoon.

Fig. 9.

Weighting function σ(i, k, .) for the mobilty matrix, for any pair of regions (i, k).

The simulation results of the considered network model for 13 regions in France are shown in Figures 10 and 11 , all parameters and the values of all states at the starting date of lockdown have been identified during lockdown, the end date of confinement is 11th of May in France. Note that the end of simulation horizon on Figures 10 and 11 is the beginning of August, thus the calibrated parameters appear to fit very well to the data during 2.5 months, which is very positive.

Fig. 10.

Minimap of regions in France, and the simulation of the pandemic network model for the first 7 regions among 13.

Fig. 11.

Simulation of the pandemic network model for the last 6 regions among 13.

5. Network of cities

In this section, we use the parameter identification method developed in Section 3 to simulate another network of areas. Instead of considering the network of the 13 metropolitan regions as in Section 4, we consider the network of all French cities. There are around 36.000 cities in France, and INSEE measures the displacement of people between each couple of cities (INSEE, 2020). To simulate the transport effect on the pandemic dynamics, we follow the same approach as in Section 4. To be more specific, we use the same model as (22)-(29) but instead of considering regions, we consider cities:

| (31) |

| (32) |

| (33) |

| (34) |

| (35) |

| (36) |

| (37) |

| (38) |

where Lki is the number of individuals moving from city k to city i, and is derived from the real data of INSEE, and Ci is the set of all cities that have pandemic transmission with city i. All the other parameters are chosen as the ones of the region to which each city belongs.

To simulate this system of 8*36.000 differential equations, we now specify initial conditions. To simplify, the epidemic start date of each city is taken as the same as the epidemic start date of the region to which it belongs, and the initial condition for the undetected infected individuals for the capital of each region is the one of the region, while it is set to 0 for all other cities in the region. It is equivalent to say that the pandemic dynamics starts at the capital of each region. The population of each French city is used as initial condition for the susceptible individuals.

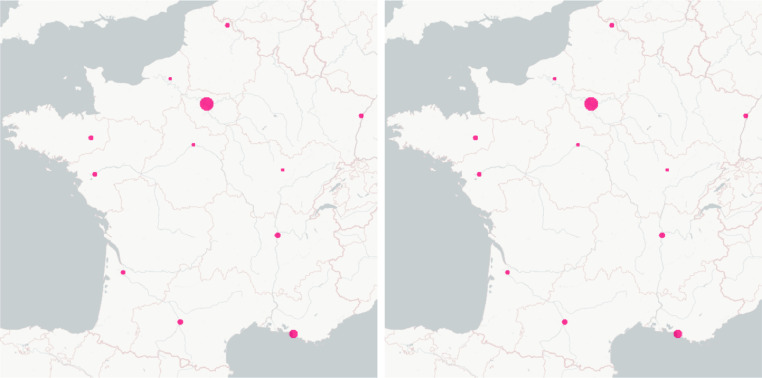

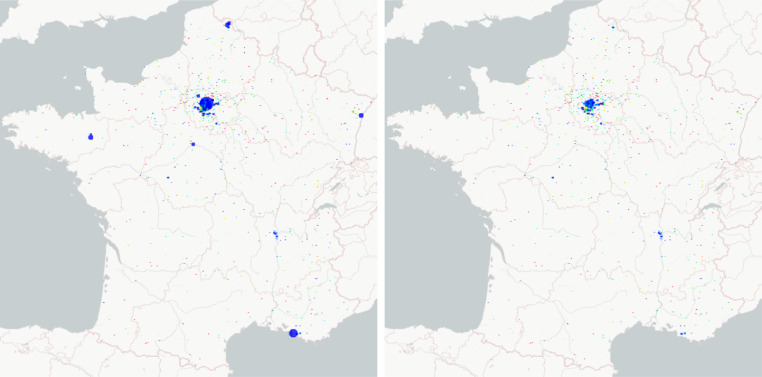

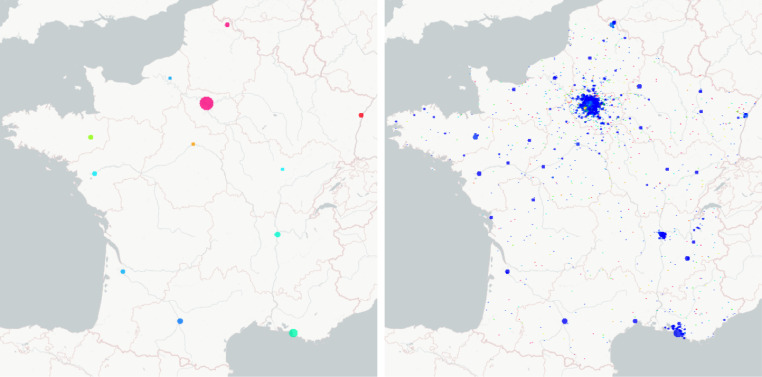

The transport effect between cities is seen on Figures 12 -14.

Fig. 12.

The maps of the transport effect between cities in France (undetected infected plus detected infected from 0% (blue) to 2% (magenta) of the population for each commune): the date for the map on the left is 2020-03-17 (start date of the lockdown in France) and the one for the map on the right is 2020-04-01.

Fig. 14.

The maps of the transport effect between cities in France(undetected infected plus detected infected from 0% (blue) to 2% (magenta) of the population for each commune): the date for the map on the left is 2020-07-01 and the one for the map on the right is 2020-08-01.

On these figures, we observe the spatial evolution of the pandemics between 2020-03-17 and 2020-08-01. At the early date, the results are impacted by the initial conditions. During the lockdown, the pandemic is just located at the regional capitals because no infected people can go out of the capitals (compare the left and right parts of Figure 12 with left part of Figure 13 ) and recall that the end of the lockdown in France in the 11th of May. Then the effect of transport between cities are seen after lockdown when other cities than capitals are affected see Figure 13 (right) and Figure 14. Using Figure 13 (right) and Figure 14 allows to conclude that the number of undetected infected are decreasing until the 1st of August. Note that we did not model the wearing of cloth face coverings in public settings, which could be included in the modelling of the transmission rate β(t).

Fig. 13.

The maps of the transport effect between cities in France (undetected infected plus detected infected from 0% (blue) to 2% (magenta) of the population for each commune): the date for the map on the left is 2020-05-01 and the one for the map on the right is 2020-06-01.

6. Discussion and a new integro-differential model

In this section, the general form of an integro-differential model capable of integrating different age classes and areas is introduced to discuss the transport effect of COVID-19 in France after lockdown. By ”areas” we mean a given geographical scale as the set of 13 Metropolitan regions (as considered in Section 4), or the set or all 101 French departments, or all cities (as considered in Section 5), or other geographical areas. For each age class a ∈ ages in area x ∈ areas, we consider the following integro-differential equations, for any time t ≥ 0 after confinement,

| (39) |

with

-

•ages, the set of different age classes of population, depending on the age scale under study. As an example, we can consider all scholar age classes, or elderly ages, or a mix of such age classes as the set

-

•areas, the set of different areas of population under study, depending on the considered geographical scale. As an example, considering all metropolitan regions, as considered in Section 4, yields the set

As another example, considering all French departments gives a set of 101 areas, or considering the geographical scale of French cities yield a set of around 36.000 areas, as considered in Section 5 and so on... We can even consider the set of countries to model the international transport effect when international activities become more frequent.

-

•

is the 8-vector consisting of compartments of the age class a, in the area x, at time t;

-

•For all age class a, fa(X(., x, t)) is the pandemic transmission dynamics for age class a from all other age classes in the area x at time t. Without considering the age effect, it is given by the right-hand side of systems (6)-(13). Inspired by the contact matrix approach developed in e.g. Keeling and Rohani (2011, Chapter 3, Page 76), by considering multiple age classes, the transmission term is the following integral

instead of

where β a,b,x(t) is the contact function between age classes a and b, in the area x, and at time t. Therefore the function fa is given by

where all parameters depend on the age class a and the area x; -

•

is the density of people coming (in) area x from area y ∈ areas at time t, for age class a;

-

•

is the density of people going to (out) area y ∈ areas from area x at time t, for age class a;

-

•

is the external flux coming into location x at time t in the age class a. As an example for the simulations of Section 4 (where the metropolitan regions are considered) and of Section 5 (where all French cities are considered), it is 0 because the boundary of France are close (at the time of the simulation);

-

•

σ(a, x, y, t) is a weighting function that determines the mobility between area x and area y, at time time t for the age class a. It stands for a (lockdown or no-lockdown) function for the age class a, between the areas x and y at time t. As an example, before the 11th of May, it was forbidden to travel for more than 100km in France. Such a policy could depend on the age classes and on the areas, e.g., to control so-called ”clusters” of COVID-19;

-

•

provides the total number of people coming into area x from all the other areas;

-

•

provides the total number of people coming from area x into any of the other areas.

Equation (39) describes the network dynamics of COVID-19 pandemic after lockdown and the transport effect on different age class on the basis of the regional pandemic transmission dynamics during lockdown. The interest of this model is that it could be adapted to any geographical scales, and to all age classes. For a control point of view, the most important term is σ(a, x, y, t) which defines the lockdown policy that defines the mobility between areas x and y at time t for the age class a. Many control problems could be studied for this model, as optimal control to reduce the pandemic effect, or to minimize the mortality in particular. It is of great importance for the mobility dynamics of the pandemic.

Beyond that, inspired by advection-diffusion modelling of population dynamics (as considered in Faugeras & Maury (2007)), it is natural to model the displacement inside a given area by a diffusion term (see Crank (1980)). The corresponding model is formulated as follows:

| (40) |

where the diffusion coefficient d(a, x, t) is a function that depends on age class a, areas x and time t.

This 2-order partial differential equation predicts, for age class a in the area x, how diffusion and displacement cause the number of individuals in the different compartments, especially undetected infectives and deaths. As long as one susceptible person is infected after directly or indirectly contacting disease carriers in the area x, diffusion takes place. When the number of infectious individuals in a local area is low compared to the surrounding areas, the pandemic will diffuse in from the surroundings, so the number of infectives in this area will increase. Conversely, the pandemic will diffuse out and the number of infectives will increase in the surrounding areas.

Finally, gender differentiation or other properties may be taken into account to characterize types of populations and to study the optimal lockdown control of pandemic dynamics based on our previous work. It is worth stressing that, in the long run, optimal lockdown strategies should consider the balance between the lower number of deaths and minimum healthcare and social costs.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we investigated an extended model of the classical SIRD pandemic model to characterize the regional transmission of COVID-19 after lockdown in France. Incorporating the time delays arising from incubation, testing and the complex effects of government measures, an exponential function of the transmission rate β(t) was presented for the regional model. By fitting the regional model to the real data, the optimal parameters of this regional model for each region in France were derived. Based on the previous results of the extended model, we introduced and simulated a network model of pandemic transmission between regions after confinement in France while considering age classes. Regarding the transmission rate β(t) for the network model, we selected a continuous function related to the reciprocal function of the β(t) during lockdown to contribute to the transport effect after lockdown. By using the same model and method, we simulated the pandemic network for all cities in France to visualize the transport effects of the pandemic between cities. Considering age classes, we discussed an integro-differential equation for modelling the network of infectious diseases in the discussion part.

Because of the large volumes of data and complicated calculations needed for parameters calibration and simulation when considering many geographical areas and many age classes, the requirements in terms of computer hardware and software are rather high. In order to achieve accurate results, appropriate and efficient data processing methods will be applied. Moreover appropriate dedicated theoretical work is needed to study the integro-differential model derived in Section 6.

In future works, we will formulate and study optimal control problems in order to balance the induced sanitary and economic costs. The lockdown strategies implemented in France should be evaluated and compared to the proposed optimal strategies.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very greatfull to Sébastien Da Veiga, Senior Expert in Statistics and Optimization at SafranTech (France) for the R codes used for calibration and uncertainty calibration.

Footnotes

This work has been partially supported by French National Research Agency in the framework of the Investissements d’Avenir program (ANR-15-IDEX-02), MIAI @ Grenoble Alpes (ANR-19- P3IA-0003), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant No. 61873007), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 1182001), and a research grant from project PHC CAI YUANPEI (Grant No. 44029QD).*Institute of Engineering Univ. Grenoble Alpes

References

- Al-Tawfiq J.A. Asymptomatic coronavirus infection: MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2020;35:101608. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger D.W., Herkenhoff K.F., Mongey S. Technical Report 26901. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. An SEIR Infectious Disease Model with Testing and Conditional Quarantine. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bin M., Cheung P., Crisostomi E., Ferraro P., Lhachemi H., Murray-Smith R.…Stone L. On fast multi-shot COVID-19 interventions for post lock-down mitigation. arXiv:2003.09930

- Brauer F., Castillo-Chavez C. Vol. 2. Springer; 2012. Mathematical Models in Population Biology and Epidemiology. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier A., Elie R., Laurière M., Tran V.C. COVID-19 pandemic control: balancing detection policy and lockdown intervention under ICU sustainability. arXiv:2005.06526v3

- Crank J. Oxford University Press; 1980. The Mathematics of diffusion. [Google Scholar]

- Day M. Covid-19: identifying and isolating asymptomatic people helped eliminate virus in Italian village. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2020;368:m1165. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faugeras B., Maury O. Modeling fish population movements: from an individual-based representation to an advection–diffusion equation. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2007;247(4):837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FranceTvInfo (2020). Coronavirus : 450 personnes en quatorzaine après des cas de Covid-19 déclarés dans une école de Lyon. https://www.francetvinfo.fr/sante/maladie/coronavirus/coronavirus-450-personnes-en-quatorzaine-apres-des-cas-dans-une-ecole-de-lyon_4036889.html, accessed July 9, 2020.

- Gostic K., Gomez A.C., Mummah R.O., Kucharski A.J., Lloyd-Smith J.O. Estimated effectiveness of symptom and risk screening to prevent the spread of COVID-19. eLife. 2020;9:e55570. doi: 10.7554/eLife.55570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouvernement français (2020). Info coronavirus covid 19. https://www.gouvernement.fr/info-coronavirus/carte-et-donnees, accessed July 9, 2020.

- INSEE (2020). Mobilités professionnelles et scolaires en france. https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/2383243 and https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/2383297, accessed July 9, 2020.

- Keeling M.J., Rohani P. Princeton University Press; 2008. Modeling infectious diseases in humans and animals. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling M.J., Rohani P. Princeton University Press; 2011. Modeling infectious diseases in humans and animals. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski A.J., Russell T.W., Diamond C., Liu Y., Edmunds J., Funk S., Eggo R.M. Early dynamics of transmission and control of COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20:553–558. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magal, P., & Webb, G.. Predicting the number of reported and unreported cases for the COVID-19 epidemic in South Korea, Italy, France and Germany,. 10.2139/ssrn.3557360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McKay M.D., Beckman R.J., Conover W.J. A comparison of three methods for selecting values of input variables in the analysis of output from a computer code. Technometrics. 2000;42(1):55–61. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1979.10489755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministère des solidarités et de la santé (2020). Plateforme COVID-19. https://covid-19.sante.gouv.fr/login?to=/ressources, accessed July 9, 2020.

- Moré J.J. Numerical analysis. Springer; 1978. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm: implementation and theory; pp. 105–116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pardoux E., Britton T. Springer; 2019. Stochastic Epidemic Models with Inference. [Google Scholar]

- Prague M., Wittkop L., Clairon Q., Dutartre D., Thiébaut R., Hejblum B.P. Population modeling of early COVID-19 epidemic dynamics in French regions and estimation of the lockdown impact on infection rate. medRXiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.21.20073536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roques, L., Klein, E. K., Papaix, J. J., Sar, A., & Soubeyrand, S. (2020). Effect of a one-month lockdown on the epidemic dynamics of COVID-19 in France. 10.1101/2020.04.21.20074054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sobol’ I.M. On the distribution of points in a cube and the approximate evaluation of integrals. Zhurnal Vychislitel’noi Matematiki i Matematicheskoi Fiziki. 1967;7(4):784–802. doi: 10.1016/0041-5553(67)90144-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tillett H.E. Infectious diseases of humans: Dynamics and control. R. M. Anderson, R. M. May, Pp. 757. Oxford University Press, 1991. Epidemiology and Infection. 1992;108(1) doi: 10.1017/S0950268800059896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; 211–211.

- Veiga S.D., Gamboa F., Iooss B., Prieur C. SIAM; 2020. Basics and trends in sensitivity analysis. Theory and practice in R. [Google Scholar]