Abstract

Purpose

Batracylin (daniquidone), an ATP-insensitive topoisomerase I/II inhibitor, demonstrated wide interspecies variation in preclinical models consistent with formation of a toxic metabolite, N-acetyl-batracylin, following metabolism by N-acetyl-transferase 2 (NAT2). To minimize exposure to this toxic metabolite, this first-in-human study was conducted in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors or lymphomas demonstrated to have a slow NAT2 acetylator genotype. The objectives were to determine the safety, maximum tolerated dose (MTD), and pharmacokinetics of batracylin and its metabolites.

Methods

Based on the MTD for rats, the most sensitive species, the starting dose was 5 mg/day for 7 days in 28-day cycles. Dose escalation followed accelerated titration design 4B, with restaging performed every 2 cycles.

Results

Thirty-one patients were enrolled. Treatment was well tolerated; one patient experienced grade 3 toxicity (lymphopenia). Dose escalation was stopped at 400 mg/day due to grade 1 and 2 hemorrhagic cystitis. No objective responses were observed, but prolonged disease stabilization was observed in 2 patients, one with peritoneal mesothelioma (8 cycles) and another with adrenocortical cancer (18 cycles). Across an 80-fold range of doses, the ratios of systemic exposures for batracylin and N-acetyl batracylin were near 1.

Conclusions

Pharmacogenetically selected patients reached a dose that was 20-fold higher than the MTD in rats and 70 % of the MTD in mice. This genotype-guided strategy was successful in safely delivering batracylin to patients. However, due to unexpected cystitis, not preventable by hydration, and in the absence of a stronger signal for antitumor activity, further development of batracylin has been stopped.

Keywords: Pharmacogenetics, N-acetyl-batracylin, NAT2

Introduction

Batracylin (8-aminoisoindolo [1,2-b]quinazolin-12(10H)-one; daniquidone), a synthetic heterocyclic amine, underwent preclinical development as an experimental antitumor agent by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the late 1980s. Batracylin was categorized as an ATP-insensitive topoisomerase I and II inhibitor that showed promising antitumor activity in preclinical models, especially in tumors resistant to cisplatin or doxorubicin [1–4]. Oral administration of batracylin to rats, mice, and dogs for 9 days resulted in maximum tolerated doses (MTD) of 12, 360, and >720 mg/m2, respectively (data on file, Developmental Therapeutics Program, NCI). Toxicities observed across all species evaluated included diarrhea, soft stools, rough hair coat, lethargy, myelosuppression, hunched posture, emaciation, and dehydration. Progression of this agent to the clinic was halted due to the safety concerns raised by the wide interspecies variability in tolerance.

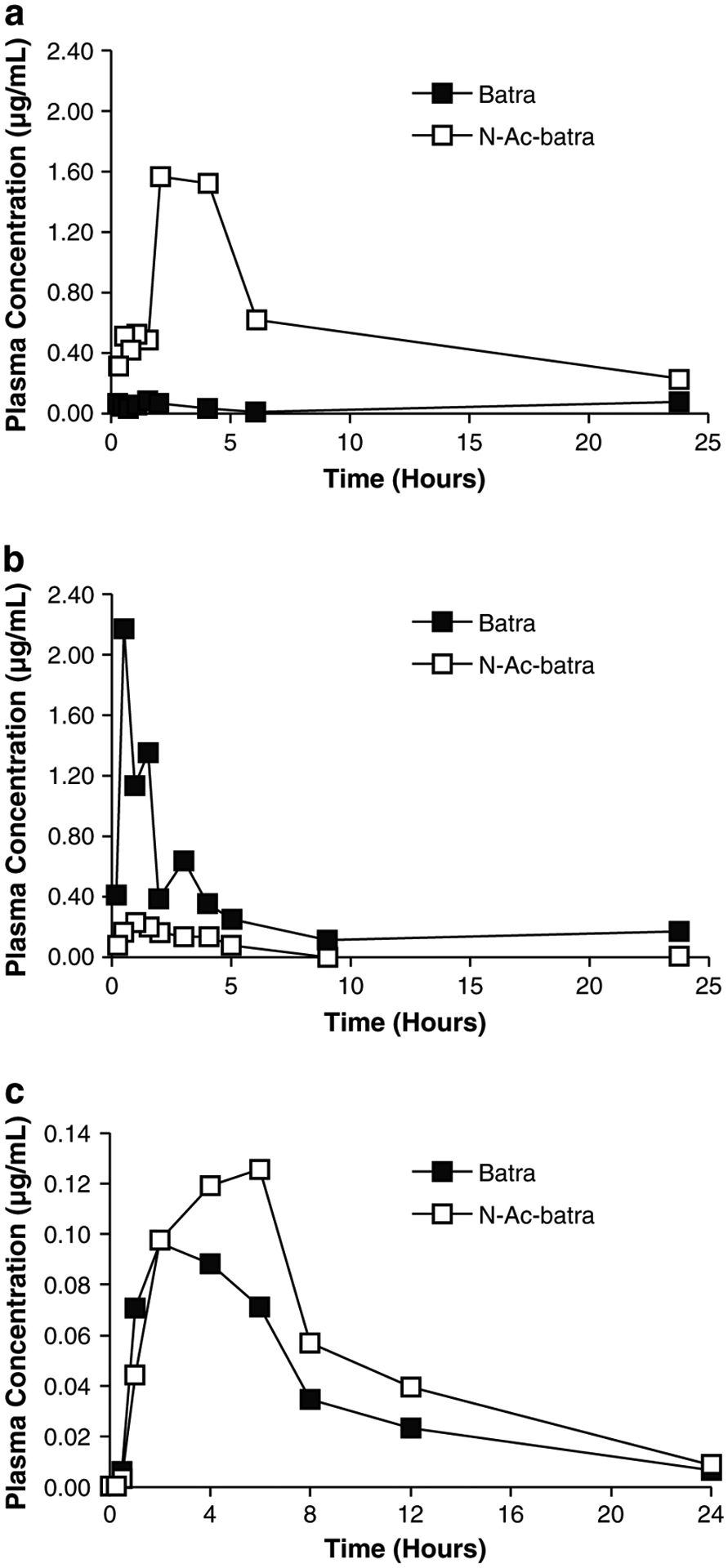

Further investigation revealed that the interspecies variation in batracylin toxicity was consistent with the pattern of metabolism of the parent compound by N-acetyl-transferase 2 (NAT2) to the acetylated form, N-acetyl-batracylin (N-Ac-batracylin), a highly toxic molecule [5, 6]. Following administration of 590 mg/m2 of batracylin to mice and rats, the relative exposure for parent batracylin in rats was only 1/7 of the plasma exposure in mice based on the area under the curve (AUC); in contrast, the AUC for the metabolite N-Ac-batracylin in rats was 8.8-fold higher than in mice (Fig. 1a, b) [5]. These results suggested that mice and rats experience toxicity to batracylin at widely different exposures to parent drug, but in a similar range of exposure to N-Ac-batracylin. The higher tolerance of dogs to batracylin was associated with the absence of N-Ac-batracylin in the plasma. This finding is consistent with reports that the canine genome does not code for arylamine N-acetylation [7].

Fig. 1.

a Batracylin (filled square) and N-Ac-batracylin (open square) data for rats following 590 mg/m2. b Corresponding batracylin (filled square) and N-Ac-batracylin (open square) data for mice. a and b Reproduced with permission from Ames et al. [5]. c Plasma concentration versus time curves for batracylin (filled square) and N-Ac-batracylin (open square) from a patient in this study following the first dose of 280 mg of batracylin. Linear scales and units of μg/mL were used to match the published data

Humans have a polymorphic pattern of NAT2 activity, with a number of different alleles giving rise to amino acid substitutions resulting in the absence of catalytic activity in vitro [8]. Screening for four variant alleles (NAT2*5, NAT2*6, NAT2*7, and NAT2*14) identifies individuals who are slow acetylators. We hypothesized that batracylin could be administered safely to patients with the slow acetylator NAT2 genotype because the conversion to N-Ac-batracylin would be sufficiently low with adequate time for clearance to minimize high exposures to the toxic metabolite.

We conducted a phase 1 trial of batracylin to establish the safety, tolerability, MTD, and pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of batracylin in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors and lymphomas and a slow acetylator NAT2 genotype defined as NAT2*5, NAT2*6, NAT2*7, or NAT2*14.

Patients and methods

Eligibility criteria

Eligible patients had histologically documented solid tumors or low-grade lymphoid malignancies that were refractory to standard therapy. All patients were required to have a slow acetylator NAT2 genotype defined as NAT2*5, NAT2*6, NAT2*7, or NAT2*14 determined by testing [8] performed at a CLIA-certified laboratory; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤2; adequate marrow and organ function defined as leukocytes ≥3,000/μL, absolute neutrophil count ≥1,500/μL, platelets ≥100,000/μL, total bilirubin ≤1.5 × the upper limit of normal (ULN), aspartate aminotransferase and/or alanine aminotransferase <2.5 × ULN, and creatinine <1.5 × ULN; and an ability to swallow pills without difficulty. Prior anticancer therapy must have been completed at least 4 weeks prior to enrollment. Patients were excluded if they had an uncontrolled intercurrent illness or were pregnant or lactating.

This trial was conducted under an NCI-sponsored IND with institutional review board approval. The protocol design and conduct complied with all applicable regulations, guidance, and local policies (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00450502).

Trial design

This was an open-label, single-arm phase 1 study of batracylin administrated orally once a day for 7 consecutive days, in 28-day cycles. Batracylin was supplied by the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, NCI. In addition to NAT2 genotyping, PK data were obtained on day 1 of the first 3 days of dosing on cycle 1 to ensure patient safety—only if day 1 PK data (available by day 4) remained consistent with the slow acetylator phenotype, dosing for days 4–7 and subsequent cycles continued. If PK data from day 1 were consistent with a fast acetylator phenotype, the patient would not receive additional batracylin treatment and would be taken off study.

The starting dose was 5 mg given by mouth daily on an empty stomach for 7 days, based on the LD10 in rats, the most sensitive species (Table 1). Dose escalation proceeded according to accelerated titration design 4B [9] with one patient per dose level with 100 % dose increments between dose levels until one patient developed dose-limiting toxicity (DLT); two patients developed grade 2 toxicity; or the N-Ac-batracylin AUC reached 0.16 μM h (50 % of the lower end of the exposure range in the rat). Further dose escalation and enrollment followed a traditional 3 + 3 design.

Table 1.

Dose escalation schedule

The MTD was defined as the dose at which no more than 1 of 6 patients or 33 % or less experienced a DLT. Adverse events were graded according to NCI Common Terminology Criteria version 3.0. A DLT was defined as an adverse event that occurred in the first cycle, was believed to be study drug related, and fulfilled one of the following criteria: grade 3 or higher non-hematologic toxicity (except for nausea/vomiting and diarrhea without maximal symptomatic/prophylactic treatment); grade 4 thrombocytopenia; grade 4 neutropenia lasting >5 days; febrile neutropenia; or grade 4 anemia. Any degree of leucopenia in the absence of neutropenia as defined above, or lymphopenia, was not considered dose limiting. Non-hematologic toxicities should have resolved to ≤grade 1 and hematologic toxicities to ≤grade 2 prior to starting the next cycle. Treatment could be delayed for a maximum of 2 weeks beyond the actual cycle length of 28 days. Occurrence of DLT resulted in holding the study drug until resolution of toxicity as defined above, with restarting at the next lower dose.

Intra-patient dose escalation was permitted only if there was no batracylin-related toxicity greater than grade 1 after a course at the initial dose level (DL), higher doses were evaluated in at least one patient without DLT, and disease had not progressed.

Safety and efficacy evaluations

Complete history and physical examination were performed at baseline and prior to each cycle. Complete blood counts with differential and serum chemistries were performed at baseline, weekly for the first 2 cycles, and then prior to each cycle. More frequent assessment of blood counts was performed for patients experiencing grade 3 and 4 myelosuppression to determine the duration of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia and to document recovery. Radiographic evaluation was performed at baseline and every 2 cycles to assess for tumor response based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.0) [10].

Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples (7 mL) for PK analysis were collected during cycle 1 at baseline prior to drug administration and then at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h post-dose on days 1 and 7 of cycle 1. Samples were centrifuged and plasma stored at −20 °C until analysis. Urine output was collected over 24 h, and aliquots of each void were frozen at −20 °C until analysis. Reference compounds batracylin (NSC 320846), N-Ac-batracylin, and N-propyl-batracylin were supplied by the Developmental Therapeutics Program, NCI (Bethesda, MD, USA). Calibration curves were constructed by adding known amounts of batracylin and N-Ac-batracylin as controls (concentrations of each compound ranging from 0.8 nM to 4 μM). Separation of batracylin and N-Ac-batracylin was performed by HPLC on a C18 column. The mobile phase consisted of 5 % isopropanol, 95 % 190 mM formic acid, and 0.05 % tri-ethylamine with a gradient of 25–95 % acetonitrile. Detection and identification of batracylin, N-Ac-batracylin, and N-propyl-batracylin were accomplished by fluorescence monitoring (excitation at 400 nm, emission at 560 nm). The peak areas of the compounds of interest were compared to the peak areas of the internal standard (N-propyl-batracylin). The detector response was found to be linear over this range of concentrations.

Results

Demographics

A total of 31 patients were enrolled from February 2007 to July 2010; patient characteristics are provided in Table 2. One patient withdrew from the study, two patients were taken off treatment for an elevated metabolite ratio (and were re-treated following a clinical protocol amendment), three patients were taken off treatment for an adverse event or side effects, and 27 patients were taken off treatment for disease progression.

Table 2.

Patient’s characteristics

| No. of patients | 31 |

| Male | 19 |

| Female | 12 |

| Age, years | |

| Median (range) | 60 (19–75) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 26 |

| 2 | 3 |

| Tumor types | |

| Colorectal | 10 |

| Peritoneal mesothelioma | 1 |

| Head and neck | 3 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 1 |

| Urothelial | 1 |

| Breast | 1 |

| Adrenocortical | 4 |

| Ovarian | 1 |

| Prostate | 1 |

| Gallbladder/bile duct | 2 |

| Pancreas | 3 |

| Desmoplastic round blue cell | 1 |

| Melanoma | 1 |

| Lymphoma | 1 |

| No. of lines of prior systemic therapies (range) | 1–7 |

ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Activity

No objective responses were observed. Two patients had prolonged disease stabilization: one with peritoneal mesothelioma received 8 cycles of study drug and 1 patient with adrenocortical cancer received 18 cycles.

Toxicity

Two patients were enrolled onto DL 1, and PK sampling was performed to monitor the ratio of metabolite-to-parent concentration (N-Ac-batracylin/batracylin). The ratio in the first patient was 10-fold higher than the ratio in mice, while the second patient’s exposure to batracylin was not measurable. Both patients received less than 1 cycle and were taken off treatment for an elevated metabolite-to-parent concentration ratio. After further review of these data, and because both patients had tolerated treatment well, it was concluded that the toxicity of batracylin, as with other drugs, depends upon the actual exposure to the drug and metabolite rather than the relative ratio of the two. The protocol was therefore amended to replace the criterion of ratio with primary monitoring of exposure to N-Ac-batracylin. The amendment allowed the first two patients to be re-enrolled and treated. They tolerated study treatment well for 2 cycles each and were taken off study for disease progression.

On DL 4 (40 mg), N-Ac-batracylin AUC values reached 0.19 μM h, and the dose escalation strategy was switched to the 3 + 3 design. Dose escalation continued until DL 11 without significant toxicities (Table 3). Four patients were enrolled on DL 11 (400 mg); one patient had disease-related complications, was unable to complete the first course, and was replaced. Two patients completed cycle 1 but developed grade 1 cystitis, which was self-limiting and resolved without intervention. One patient developed grade 2 cystitis (gross hematuria, dysuria) that required intravenous (IV) hydration and interruption of study drug. Cystoscopy revealed areas of inflammation and hemorrhage in the bladder. Hematuria resolved with conservative measures, and the patient was taken off study. This toxicity prompted an amendment to administer IV or oral hydration (>1 L per day) on days 1–7 of each cycle. Two additional patients were enrolled onto the next lower dose level (DL 10, 280 mg), and urinalysis was performed each day during days 1–7 of the first cycle to assess for hematuria. Study drug was held for RBCs > 300/mcL. The first patient developed grade 2 cystitis, proteinuria, urinary frequency/urgency, and grade 1 hemoglobinuria despite oral hydration later in cycle 1. The second patient developed grade 1 hemoglobinuria without urinary frequency on cycle 2. Hydration did not protect against drug-induced cystitis, and both patients were taken off treatment for safety.

Table 3.

Adverse events at least possibly related to study medication

| Adverse events | Gradea (no. of patients) |

|---|---|

| Alanine aminotransferase | 1(1) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 1(1) |

| Anorexia | 2(1) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 1(2) |

| Creatine phosphokinase | 2(1) |

| Cystitis | 1(1) |

| 2(1) | |

| Diarrhea | 1(1) |

| Fatigue | 1(3) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 2(1) |

| Hemoglobin | 1(1) |

| 2(1) | |

| 3(1) | |

| Hemoglobinuria | 1(2) |

| Hemorrhage | 1(1) |

| Leukocytes | 1(1) |

| Lymphopenia | 1(4) |

| 2(2) | |

| 3(1) | |

| Nausea | 1(2) |

| 2(1) | |

| Neuropathy | 1(1) |

| Pain | 2(1) |

| Platelets | 1(5) |

| Proteinuria | 2(1) |

| Urinary frequency | 2(1) |

| Vomiting | 1(2) |

| 2(1) |

Worst grade reported per patient

Because hydration did not protect patients from bladder toxicity and in the absence of a predictive animal model to test co-administration of protective agents such as mesna, the study was terminated.

Pharmacokinetics

The time courses for plasma concentrations of batracylin and N-Ac-batracylin (Fig. 1c) are shown for a representative patient on day 1 following a dose of 280 mg. The concentration of batracylin rose for 2–6 h following dosing. By 24 h, the batracylin concentration had declined by at least 10-fold from its maximum value. The pattern of concentrations for N-Ac-batracylin tended to follow a similar time course. The exposures in humans were very similar for batracylin and N-Ac-batracylin. In contrast, published data [5] showed that batracylin concentrations dominated the exposure for mice and N-Ac-batracylin concentrations dominated the exposure for rats (Fig. 1a, b).

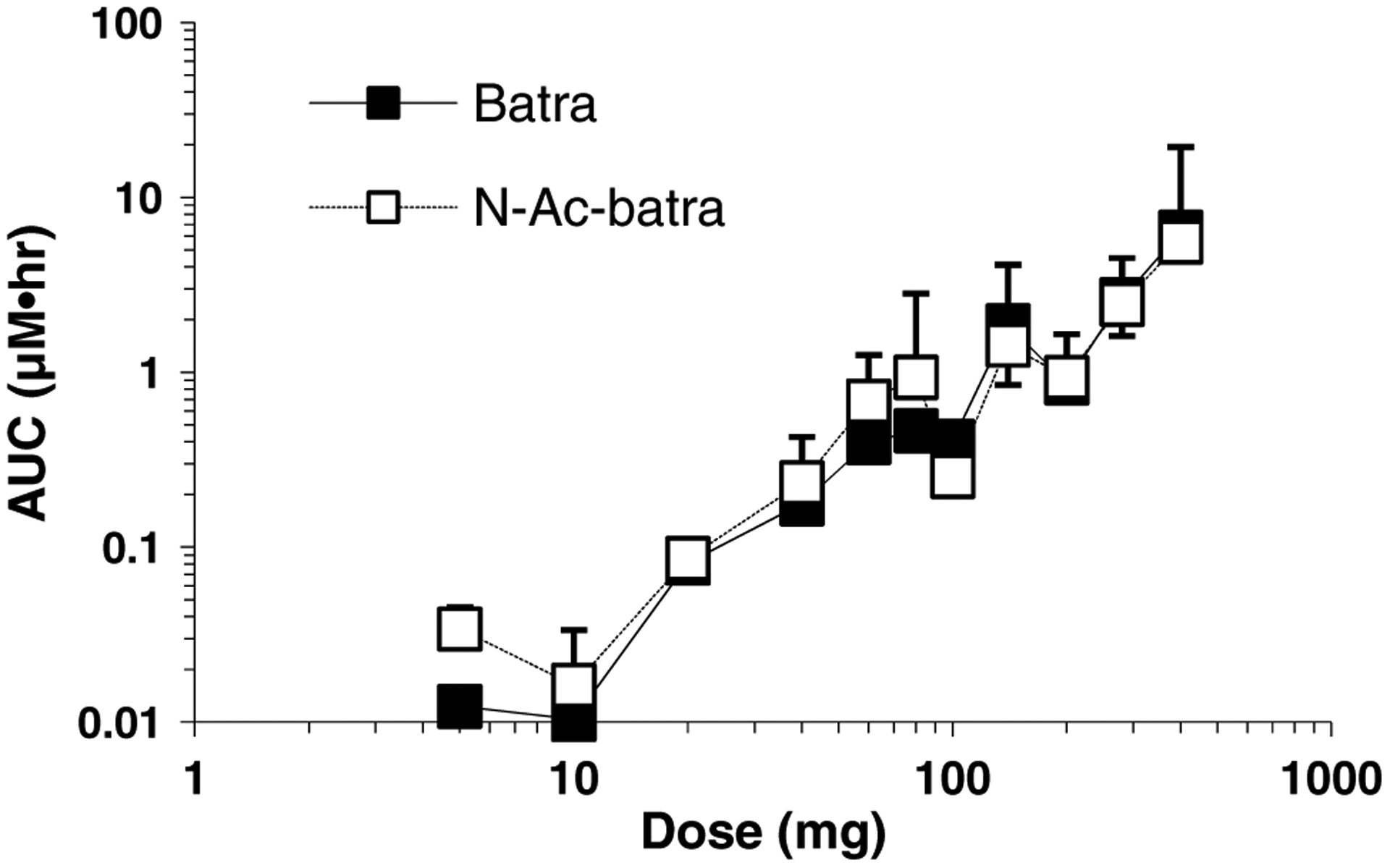

Batracylin and N-Ac-batracylin AUC data for all patients are plotted in Fig. 2. Because the full range of doses varied 80-fold (from 5 to 400 mg), the data are graphed on a log-log plot. These data reinforce the observation that human exposure to batracylin and N-Ac-batracylin is similar. The mean values monotonically increased, suggesting that no kinetic processes were substantially saturated, although the increase was not quite linear. The standard deviations on the graph appear to indicate minor inter-subject variation, but that impression is somewhat artifactual due to the nature of a log–log plot. The relative standard deviation across all doses was 71 % for batracylin and 99 % for N-Ac-batracylin. Urinary recovery was less than 1 % of the dose in all patients for both batracylin and N-Ac-batracylin.

Fig. 2.

AUC in plasma for batracylin (filled square) and N-Ac-batracylin (open square) for the dose range of 5–400 mg/day. Units for AUC are μM h. Standard deviations are shown above the symbol for N-Ac-batracylin and below the symbol for batracylin. Logarithmic scales were used due to the wide dynamic range

Discussion

In oncology, most pharmacogenetic efforts are directed toward examining the unique features of the tumor to identify potential drug targets. Nonetheless, there are compelling reasons to also consider germline differences in drug metabolism as a variable in determining both efficacy and toxicity. Inter-individual differences in drug exposure are particularly severe for compounds that have pharmacogenetic differences in metabolism. Although differences in the CYP genes have been the most frequently studied source of germline variability [11], other classes of enzymatic metabolism are also important for dose adjustments, including conjugation of the active metabolite of irinotecan via glucuronidation [12].

The early development of pharmacogenetics was strongly influenced by N-acetyl-transferases, especially the NAT2 gene; the role of NAT2 in the metabolism of isoniazid, a drug used for the treatment for tuberculosis, is well known [13]. Amonafide is the most notable example of a role for NAT2 in the metabolism of drugs used for cancer treatment. The clinical development of this investigational anticancer agent was discontinued following phase 2 studies, at least in part due to practical difficulties in selecting safe doses for patients with differing acetylator status. By the time separate amonafide doses were established for fast and slow acetylators [14], there was insufficient interest in repeating the phase 2 studies.

Either genotyping or phenotyping can be used to assess the potential for pharmacogenetic variability. The amonafide study used caffeine as a phenotypic probe. In our batracylin study, we used genotyping based upon the practicality of testing white blood cells, compared with a PK study for phenotyping. Not every metabolic pathway has documentation of the extent of association between these tools, but there is strong concordance for NAT2 [15].

This clinical investigation found that the interspecies differences in tolerance for batracylin were consistent with exposure to its toxic metabolite, N-Ac-batracylin. As shown in Table 4, the relative human exposure to N-Ac-batracylin was intermediate among mammalian species, consistent with the tolerability of batracylin in most patients.

Table 4.

N-Ac-batracylin: association between relative exposure and MTD

| Species | MTDa | Relative exposure |

|---|---|---|

| Rat | 12 | Highest |

| Human | 240b | Intermediate |

| Mouse | 360 | Middle |

| Dog | >720 | Lowest |

Doses in mg/m2/day for 7 days in patients and 9 days in preclinical studies

This human study (in patients whose genotype indicated slow acetylation) used fixed doses; the dose of 400 mg/day is equivalent to 240 mg/m2/day

Despite attempts to minimize the number of patients using accelerated titration and eligibility that was pharmacogenetically guided, 31 patients were required to complete this study. The major reason for this was the low starting dose. A higher starting dose would have decreased the number of patients required and shortened the time needed for the study. Based upon prior published data from the toxicology studies, the investigators had proposed a higher starting dose; however, given the interspecies variability in tolerance and the fact that the pharmacogenetic strategy was as yet unproven for this agent, regulatory and oversight committees mandated the lower starting dose of 5 mg to ensure patient safety. This resulted in evaluation of an 80-fold range in dosing. The review process could have chosen an even lower dose of 2 mg, based upon standard criteria for the most sensitive species. Thus, instead of an 80-fold escalation in dose, 200-fold escalation would have been required.

Because humans with the fast acetylator genotype were not studied, it remains theoretically possible that there would be no major subgroup differences in N-Ac-batracylin based upon acetylator status. However, the preponderance of evidence did not support exposing patients who were fast acetylators to potentially higher concentrations of N-Ac-batracylin, resulting in toxicity.

The observed toxicity of hemorrhagic cystitis was not expected. The general preclinical pattern for batracylin exhibited substantial variation across species, but bladder toxicity was not reported (this toxicity had not been specifically examined). Thus, once cystitis was found in humans, there was no suitable preclinical model, which could be used to guide attempts to alleviate this toxicity. Hydration was attempted, but was unsuccessful.

The genotype-guided strategy for this study successfully enabled delivery of batracylin doses to patients that were 2/3 of those in mice. However, the unanticipated toxicity in the bladder was a major setback for any attempts to continue the development of this agent. Considerable further work on model development would be required to investigate ways to mitigate this toxicity. In the absence of a substantial signal of antitumor activity, such efforts could not be justified, and the clinical development of batracylin has been stopped.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. This research was supported [in part] by the Developmental Therapeutics Program in the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None declared.

Contributor Information

Shivaani Kummar, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA; Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-9735, USA.

Martin E. Gutierrez, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA

Lawrence W. Anderson, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-9735, USA

Raymond W. Klecker, Jr., Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Alice Chen, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-9735, USA.

Anthony J. Murgo, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-9735, USA

James H. Doroshow, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-9735, USA.

Jerry M. Collins, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-9735, USA

References

- 1.Plowman J, Paull KD, Atassi G, Harrison SD Jr, Dykes DJ, Kabbe HJ, Narayanan VL, Yoder OC (1988) Preclinical antitumor activity of batracylin (NSC 320846). Invest New Drugs 6:147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waud WR, Harrison SD Jr, Gilbert KS, Laster WR Jr, Griswold DP Jr (1991) Antitumor drug cross-resistance in vivo in a cisplatin-resistant murine P388 leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 27:456–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao VA, Agama K, Holbeck S, Pommier Y (2007) Batracylin (NSC 320846), a dual inhibitor of DNA topoisomerases I and II induces histone gamma-H2AX as a biomarker of DNA damage. Cancer Res 67:9971–9979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mucci-LoRusso P, Polin L, Bissery MC, Valeriote F, Plowman J, Luk GD, Corbett TH (1989) Activity of batracylin (NSC-320846) against solid tumors of mice. Invest New Drugs 7:295–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ames MM, Mathiesen DA, Reid JM (1991) Differences in N-acetylation of the experimental antitumor agent batracylin in the mouse and the rat. Invest New Drugs 9:219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens GJ, Burkey JL, McQueen CA (2000) Toxicity of the heterocyclic amine batracylin: investigation of rodent N-acetyltransferase activity and potential contribution of cytochrome P450 3A. Cell Biol Toxicol 16:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trepanier LA, Ray K, Winand NJ, Spielberg SP, Cribb AE (1997) Cytosolic arylamine n-acetyltransferase (NAT) deficiency in the dog and other canids due to an absence of NAT genes. Biochem Pharmacol 54:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doll MA, Fretland AJ, Deitz AC, Hein DW (1995) Determination of human NAT2 acetylator genotype by restriction fragment-length polymorphism and allele-specific amplification. Anal Biochem 231:413–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon R, Freidlin B, Rubinstein L, Arbuck SG, Collins J, Christian MC (1997) Accelerated titration designs for phase I clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 89:1138–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou S-F, Liu J-P, Chowbay B (2009) Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 enzymes and its clinical impact. Drug Metab Rev 41:89–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Innocenti F, Undevia SD, Iyer L, Xian Chen P, Das S, Kocherginsky M, Karrison T, Janisch L, Ramirez J, Rudin CM, Vokes EE, Ratain MJ (2004) Genetic Variants in the UDP-glucuronosyl-transferase 1A1 Gene Predict the Risk of Severe Neutropenia of Irinotecan. J Clin Oncol 22:1382–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans D, Storey P, Wittstadt F, Manley K (1960) The determination of the isoniazid inactivator phenotype. Am Rev Respir Dis 82:853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratain MJ, Mick R, Berezin F, Janisch L, Schilsky RL, Vogelzang NJ, Lane LB (1993) Phase I Study of Amonafide Dosing Based on Acetylator Phenotype. Cancer Res 53:2304–2308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith C, Wadelius M, Gough A, Harrison D, Wolf C, Rane A (1997) A simplified assay for the arylamine N-acetyltransferase 2 polymorphism validated by phenotyping with isoniazid. J Med Genet 34:758–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]