Summary

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDA) with high stromal content are shown to have greatly reduced overall survival, consistent with previous reports that stroma can limit drug delivery. In contrast to expectations, metastatic lesions were found to harbor as much stroma as primary tumors.

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, Whatcott and colleagues overturn an entrenched dogma in the pancreatic cancer field: the belief that metastatic lesions have less stroma than primary tumors (1). Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is an aggressive cancer with median overall survival of 6 - 10 months and a 5-year survival rate of just 7% (2). PDA rapidly metastasizes to the liver, lung, and peritoneum and the majority of patients eventually succumb with widespread metastatic burden.

A striking pathological feature of the disease is the extensive fibroinflammatory stroma that can dominate up to 90% of the area of the tumor. This stromal “desmoplasia” is composed of dozens of distinct cell types (fibroblasts, myeloid and lymphoid lineages, endothelial cells, and neuronal cells) as well as an extracellular matrix (ECM) composed of a complex arrangement of macromolecular constituents such as hyaluronic acid and various collagens. The role played by the stroma in tumor pathology has been a point of conjecture and study for over 150 years (3). Originally viewed as an inflammatory response to a “wound that does not heal”, the stroma is now understood to play a dynamic and active role in disease pathogenesis, with elements that can both promote and restrain cancer. For example, multiple stromal cell types contribute to create a highly immunosuppressive microenvironment that is critical to tumor maintenance. Conversely, certain stromal fibroblasts convey pro-differentiation signals to the neoplastic epithelium that can serve to limit tumor growth (4, 5). One surprising feature of pancreatic cancer stroma is that it contains relatively few functional blood vessels, due at least in part to the effects of high interstitial fluid pressure (6, 7).

Earlier studies of mouse and human pancreatic tumors led to the understanding that the ECM-rich, vasculature-poor stroma of PDA limits the delivery of small molecules into the tumor parenchyma (7). This realization has led to several mechanistically distinct efforts to therapeutically target the tumor stroma in order to facilitate drug delivery (6-9). Initial clinical efforts to target stromal fibroblasts using Smoothened inhibitors were unsuccessful due to unexpected negative consequences from the loss of tumor fibroblasts (5, 10). However, efforts to target ECM components should achieve the same goal while leaving fibroblasts intact. One such agent, PEGPH20 (Halozyme Therapeutics) is currently in Phase II clinical trials.

It is in this context that Whatcott and colleagues provide a fundamental description of the stromal content of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas- a dataset that was glaringly absent from the literature. In particular, they focused on the stromal content of primary tumors compared to metastases because of the common belief that metastases do not have as much stroma as primary tumors. Given the extensive metastatic burden found in most late-stage patients, if this were true one might predict that stroma-targeted therapy combinations will be effective in reducing primary tumor volume but prove less effective in restraining metastases and, by extension, in extending patient survival.

Whatcott et al carried out a pathology analysis on a collection of primary and metastatic pancreatic tumors. Through extensive quantification of unmatched primary and metastatic tissue samples from 50 patients, as well as matched samples from 7 patients, they assessed the extent and character of desmoplasia in primary tumors versus metastases. Contrary to expectations, they found that primary and metastatic lesions harbor similar levels of the ECM molecules collagen I and collagen III. Metastases had slight decreases in collagen IV and hyaluronic acid and a slight increase in the activated fibroblast marker α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). Taken together, their data suggest that PDA metastases harbor a stromal composition that is largely similar to that of primary tumors.

Given these findings, one might predict that chemotherapy-treated patients with stroma-poor pancreatic tumors should live longer than those with more desmoplastic cancers. Indeed, by stratifying the tumors from their study based on expression thresholds, Whatcott and colleagues found that patients with high levels of collagen I, collagen IV, or hyaluronic acid had significantly reduced overall survival (and a similar, but non-significant, trend for collagen III). In contrast, there was no difference in overall survival for tumors with high versus low α-SMA expression. These results are consistent with the idea that the desmoplastic stroma of PDA interferes with drug delivery. However, this point could not be directly addressed because, unfortunately, treatment data were not available for the patients in this cohort. The alternative possibility is that ECM components directly promote tumor progression independent of drug treatment. Another implication is that tumors with low ECM content may not benefit as much from stroma-targeted therapies. Indeed, a post-hoc subgroup analysis of PDA patients in a Phase I trial of PEGPH20 + gemcitabine found that the partial response rate was twice as high in tumors with elevated hyaluronic acid staining compared to low (11).

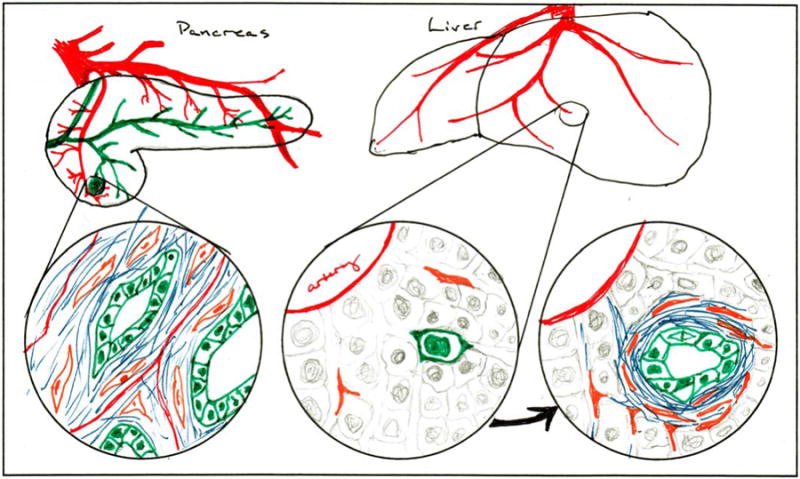

The fibroinflammatory stroma observed in metastatic lesions is not present when the first metastatic cells arrive in a distal tissue bed. A healthy liver contains a small number of hepatic stellate cells (a type of fibroblast) and very little collagen. Tumor cells arrive from the vasculature and lodge in the liver sinusoids as single cells or perhaps small clusters. They then dramatically remodel their local environment to replicate their previous home (Fig. 1). But why do this? What is the selective pressure that leads to this outcome?

Figure 1.

In primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (left circle), neoplastic epithelial cells (green) are embedded in a dense fibroinflammatory (blue) matrix laid down by fibroblasts (orange) and other stromal cell types. When metastasizing tumor cells colonize distant sites such as the liver (middle circle), they initially encounter a harsh and unreceptive environment. However, successful metastatic cells reestablish the desmoplastic stroma to a similar extent as found at the primary site (right circle).

The most obvious answer is that micrometastases must evade engagement by the host immune system. A single pancreatic tumor cell travelling through the body is put at mortal risk by neo-antigens expressed from the dozens of genetic alterations typically found in its genome. Experiments that measure the frequency of circulating tumor cells in the blood of pancreatic cancer patients have found that there are large numbers of tumor cells shed into circulation (12). Yet the number of established metastases that arise in most patients is low by comparison, suggesting that the immune system is actually quite efficient at hunting them down. To survive, the nascent metastatic cell must quickly re-establish an immunosuppressive microenvironment. If epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) facilitates invasion, intravasation, and survival in circulation, then perhaps reversion to a more epithelial phenotype promotes survival following arrival at the metastatic niche. Paracrine signals that promote desmoplasia beginning at the earliest stages of neoplasia may be reengaged to attract stromal cells. It makes sense that successful metastatic cells would use familiar signaling programs; evolution works with existing tools.

The work of Whatcott and colleagues provides fundamental data about the composition of pancreatic tumor stroma. In addition to overturning the dogma that metastases are stroma-poor, it establishes a basic connection between stroma and overall survival that must be further explored. With the understanding that stroma may limit drug delivery to both metastases and primary tumors, we look forward with anticipation to the outcomes of ongoing clinical trials of ECM-targeted therapies.

Acknowledgments

Funding: K.Olive was supported by the NIH under award numbers R01CA157980 and R21CA188857

Footnotes

Discosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Whatcott CJD, Diep CH, Jiang P, Watanabe A, LoBello J, Sima C, et al. Desmoplasia in primary tumors and metastatic lesions of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Feb 18; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1051. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal-redux. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1–11. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhim AD, Oberstein PE, Thomas DH, Mirek ET, Palermo CF, Sastra SA, et al. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:735–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, Zheng X, Wu CC, Simpson TR, et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:719–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neesse A, Frese KK, Bapiro TE, Nakagawa T, Sternlicht MD, Seeley TW, et al. CTGF antagonism with mAb FG-3019 enhances chemotherapy response without increasing drug delivery in murine ductal pancreas cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300415110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobetz MA, Chan DS, Neesse A, Bapiro TE, Cook N, Frese KK, et al. Hyaluronan impairs vascular function and drug delivery in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62:112–20. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhim AD, Oberstein PE, Thomas DH, Mirek ET, Palermo CF, Sastra SA, et al. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:735–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hingorani SR, Thaddeus J, Berdov BA, Wagner SA, Pshevlotsky EM, Tjulandin SA. A phase 1b study of gemcitabine plus PEGPH20 (pegylated recombinant human hyaluronidase) in patients with stage IV previously untreated pancreatic cancer; Proceeding of the European Cancer Congress 2013; 2013 Sep 27-Oct 1; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Brussels (Belgium): ECCO. abstract. 2013. Abstract nr 2598. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhim AD, Thege FI, Santana SM, Lannin TB, Saha TN, Tsai S, et al. Detection of circulating pancreas epithelial cells in patients with pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:647–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]