Abstract

Background:

The anterior approach to the hip joint is widely used in pediatric and adult orthopaedic surgery, including hip arthroplasty. Atrophy of the tensor fasciae latae muscle has been observed in some cases, despite the use of this internervous approach. We evaluated the nerve supply to the tensor fasciae latae and its potential risk for injury during the anterior approach to the hip joint.

Methods:

Cadaveric hemipelves (n = 19) from twelve human specimens were dissected. The course of the nerve branch to the tensor fasciae latae muscle, as it derives from the superior gluteal nerve, was studied in relation to the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery where it enters the tensor fasciae latae.

Results:

The nerve supply to the tensor fasciae latae occurs in its proximal half by divisions of the inferior branch of the superior gluteal nerve. The nerve branches were regularly coursing in the deep surface on the medial border of the tensor fasciae latae muscle. In seventeen of nineteen cases, one or two nerve branches entered the tensor fasciae latae within 10 mm proximal to the entry point of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery.

Conclusions:

Coagulation of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery and the placement of retractors during the anterior approach to the hip joint carry the potential risk for injury to the motor nerve branches supplying the tensor fasciae latae.

Clinical Relevance:

During the anterior approach, the ligation or coagulation of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery should not be performed too close to the point where it enters the tensor fasciae latae. The nerve branches to the tensor fasciae latae could also be compromised by the extensive use of retractors, broaching of the femur during hip arthroplasty, or the inappropriate proximal extension of the anterior approach.

The anterior approach to the hip joint takes advantage of the internervous plane between the sartorius (femoral nerve) and tensor fasciae latae (superior gluteal nerve). The initial technique described by Hueter involved subperiosteal removal of the tensor fasciae latae from the anterior iliac crest, sectioning of the reflected head of the rectus femoris, and release of the piriformis1. Most procedures at the hip can be performed through this approach. The anterior approach remains a standard approach to the hip joint in pediatric orthopaedic surgery for septic arthritis and developmental hip dysplasia. In adult orthopaedic surgery, it is used to expose the anterolateral aspect of the acetabulum and to access the femoral head and neck for femoral head fractures, for biopsies, for the excision of ectopic bone, or for the treatment of hip infections2-8. Because the initial description of the anterior approach has been modified to avoid release of muscles or tendons from the pelvis or the femur, it has gained popularity in total hip arthroplasty and the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement9-14.

Despite its widespread use, the relation between the anterior-approach incision and the superior gluteal nerve has not been well documented. The superior gluteal nerve is a motor nerve, which derives from the posterior branches of the ventral rami of the fourth and fifth lumbar and the first sacral spinal nerves supplying the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. It is the only nerve that exits superior to the piriformis muscle and then divides into superior and inferior branches15. Both the superior and inferior branches innervate the gluteus medius and minimus muscles. In addition, the terminal branches of the inferior branch run anteriorly and supply the tensor fasciae latae16.

Several cases of superior gluteal nerve damage have been reported for the lateral (transgluteal) approach described by Hardinge and the anterolateral approach described by Watson-Jones17-22. We recently observed atrophy of the tensor fasciae latae muscle after an unproblematic total hip replacement through a direct anterior approach.

The aim of this cadaveric study was to investigate the anatomy of the terminal inferior branch of the superior gluteal nerve in relation to the tensor fasciae latae and so reveal the potential risk zones during the direct anterior approach to the hip.

Materials and Methods

Cadaveric hemipelves (n = 19) from twelve specimens (mean donor age, seventy-eight years [range, sixty-two to ninety-one years]), including seven paired and five unpaired, six male and six female, were investigated. All limbs were embalmed in a formalin-based solution. None of the cadavers showed any evidence of previous trauma or surgery involving the femur or hip joint.

The following dissection protocol was applied. Each lower limb was first placed prone on a dissection table and the hip joint was approached posteriorly as described in the literature23. The superior gluteal nerve and the superior gluteal vessels were dissected at the greater sciatic notch above the piriformis muscle. The superior gluteal nerve was traced anteriorly and laterally between the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles. The terminal inferior branch that was running to the tensor fasciae latae was located and was marked with a small metallic tube for identification during dissection through the anterior approach. The limb was then turned supine and the hip joint was exposed via a standard anterior approach.

To improve visualization, a long incision of 25 cm was made following the anterior half of the iliac crest to the anterior superior iliac spine. From there, the incision was curved downward, aiming toward the fibular head. The fascia lata was incised over the tensor fasciae latae muscle in line with the skin incision. By staying lateral to the sartorius and rectus femoris muscles, the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery was identified where it enters the tensor fasciae latae muscle and was marked. The entry point of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery, expressed as a percentage of the muscle’s length from its proximal attachment at the iliac crest to the most distal visible muscle fibers that insert into the iliotibial tract, was recorded.

Skin and superficial subcutaneous tissue were finally removed. Again, the interval between the gluteus medius and minimus (this time from an anterior direction) was prepared and the metallic tube that marked the superior gluteal nerve was localized. The terminal branch of the superior gluteal nerve was further traced anteriorly and each nerve entry point into the tensor fasciae latae muscle was recorded. The distances between the nerve entry points and the point at which the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery entered the tensor fasciae latae were measured. Nerve branches to the tensor fasciae latae were further traced intramuscularly.

Source of Funding

No external funding source was used for this study.

Results

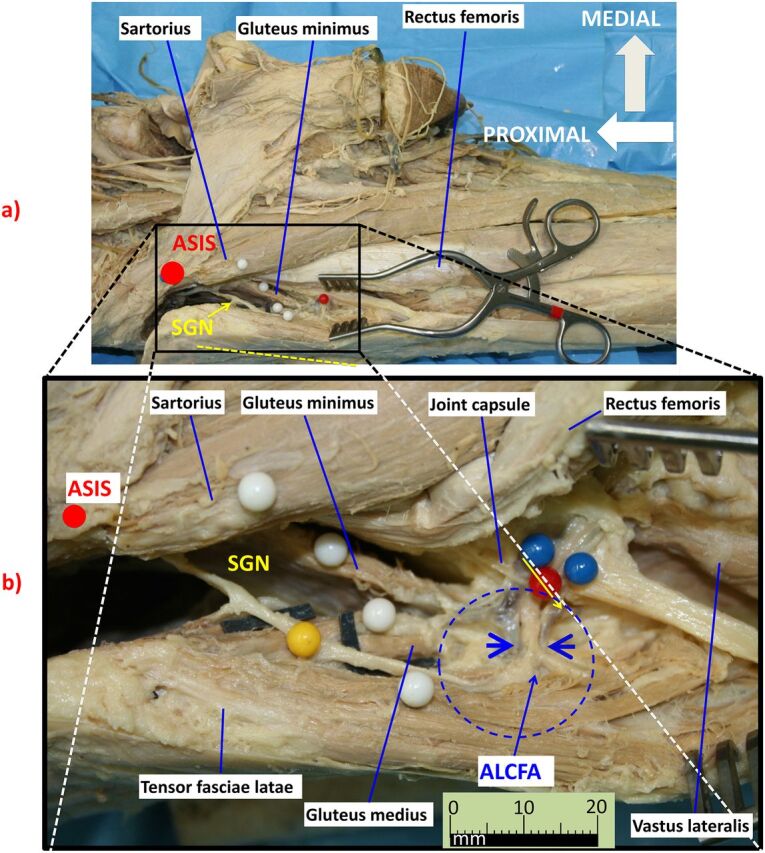

The terminal branch of the inferior division of the superior gluteal nerve entered the tensor fasciae latae in its proximal half in all cases (Fig. 1). The nerve branch approached the tensor fasciae latae on its proximal part on the posterior edge of the muscle, immediately after leaving the interval between the gluteus medius and minimus muscles (Figs. 2-A and 2-B). The nerve branch then divided into one to three muscular branches, coursing into the deep surfaces on the medial border of the tensor fasciae latae, and was covered by the thin fascia of the tensor fasciae latae. Of the nineteen cases, two nerve branches were found in fourteen cases, one nerve branch was found in four cases, and three nerve branches were found in one case.

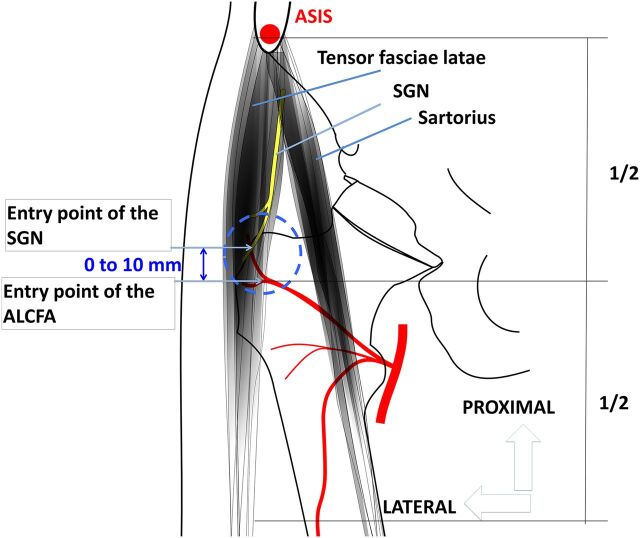

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of the right hip region. The superior gluteal nerve (SGN) entered the tensor fasciae latae muscle in its proximal half (denoted as 1/2) in all cases. No nerve supply to the tensor fasciae latae distal to the entry point of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex artery (ALCFA) could be observed. In 90% of cases, one or two terminal nerve branches entered the tensor fasciae latae just 0 to 10 mm proximal to the entry point of the ALCFA. The blue dotted line indicates the area of blood and nerve supply to the tensor fasciae latae (neurovascular hilum). The mean entry point of the ALCFA was 47% of the tensor fasciae latae muscle length from its proximal attachment to the iliac crest. ASIS = anterior superior iliac spine.

Fig. 2.

The right hemipelvis of a specimen from a male donor is shown in a standard view (Fig. 2-A) and an enlarged view (Fig. 2-B). The anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) is indicated by the red dot. In Figure 2-A, the yellow dotted line refers to the position of the skin incision of the anterior approach to the hip joint slightly lateral to the anatomical plane between the tensor fasciae latae and sartorius muscles. The terminal branch of the superior gluteal nerve (SGN) exits from the greater sciatic foramen superior to the piriformis muscle and runs anteriorly between the gluteus medius and minimus muscles (yellow arrow). The SGN courses in the deep surface on the medial border of the tensor fasciae latae and finally supplies the tensor fasciae latae close to the entry point of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (ALCFA). In Figure 2-B, the blue dotted circle indicates the neurovascular hilum. In its proximal half, the tensor fasciae latae is highly vulnerable. Extracapsular placement of retractors might endanger its nerve supply. In Figure 2-B, the blue arrowheads indicate the location where the ALCFA and its accompanying veins were ligated or were coagulated during surgery (see also Figure 3).

The intramuscular courses of these muscle branches were as follows. The most proximal nerve branch supplied the upper part of the tensor fasciae latae by extending proximally, and the distal branch supplied the lower part of the tensor fasciae latae by extending distally. In cases in which only one nerve branch entered the tensor fasciae latae, it divided intramuscularly into proximal and distal intramuscular branches. In seventeen cases, one or two terminal nerve branches entered the tensor fasciae latae between 0 and 10 mm proximal to the entry point of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (Fig. 1). The mean entry point of this artery branch was 47% (range, 41% to 54%) of the tensor fasciae latae muscle length from its proximal attachment to the iliac crest. No nerve branch entered distal to the entry point of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery.

Discussion

Recent reports on the superior gluteal nerve have focused on the lateral approach (transgluteal, according to Hardinge21), the transtrochanteric approach, or the anterolateral approach (according to Watson-Jones) to the hip and their potential dangers and safe zones18,24-26. With injury to the superior gluteal nerve, paralysis of the gluteus medius and minimus and the tensor fasciae latae muscles may occur, causing abductor weakness and a positive Trendelenburg sign18,20,22,24,27-29. The importance of preventing injury to this nerve has been emphasized18,20,22,24,27,28,30,31. The greater trochanter, posterior superior iliac spine, and anterior superior iliac spine have been described as landmarks to appropriately display the anatomy of the superior gluteal nerve. Reported distances from the apex of the greater trochanter to the inferior branch of the superior gluteal nerve ranged from 2 to 3 cm32 up to 6 to 8 cm20. Other studies defined a safe area of up to 5 cm adjacent to the greater trochanter16,24,27,33-37.

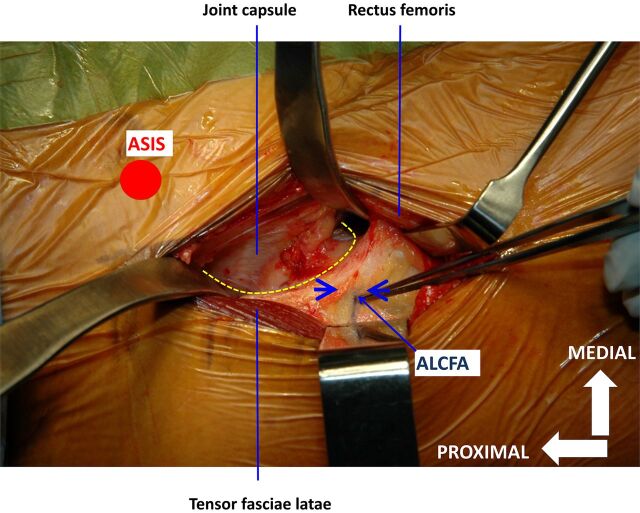

Although the anterior approach protects the nerve branches to the gluteus medius and minimus, it can affect the innervation of the tensor fasciae latae. The present study shows the result of nineteen dissections of the nerve supply to the tensor fasciae latae, with the entry point of the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery into the tensor fasciae latae as a landmark. This artery branch regularly crosses the operative field during the anterior approach to hip, in the distal portion of the wound (Fig. 3). The artery runs proximally and crosses the center of the neck of the femur on the intertrochanteric line38. To prevent bleeding complications, the ascending branch of this artery is identified and is ligated or coagulated. In 90% of cases in this study, one or two terminal nerve branches entered the tensor fasciae latae within 10 mm above the entry point of this artery branch and were always proximal to this entry point. Therefore, the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery may be a reliable landmark during surgery to protect the nerve branches to the tensor fasciae latae.

Fig. 3.

The intraoperative image of the direct anterior approach to a right hip as used for hip arthroplasty. For better exposure of the joint capsule, two extracapsular cobra retractors were placed medially and laterally to the neck of femur. A Langenbeck retractor held the rectus femoris medially and the tensor fasciae latae muscle laterally. The blue arrowheads indicate the location where the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (ALCFA) and its accompanying veins were ligated or were coagulated during surgery. The yellow dotted line indicates the authors’ preferred capsulotomy to access the hip joint. The anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) is indicated by the red dot.

In 1898, Frohse made a general statement regarding the blood and nerve supply to a muscle, indicating that the vessels have a common entrance with the nerves or enter within proximity of each other39. The results of the present study supported a neurovascular hilum or “area nervo vasculosa,” as described in the historic literature40. The neurovascular hilum of the tensor fasciae latae is located on the medial deep surface slightly proximal to the middle of the muscle (47% of the length of the tensor fasciae latae from proximal to distal). In 1955, Brash described the position of nerve entry for the tensor fasciae latae at the deep surface about in the middle of the muscle in 76% and at the deep surface near the posterior border of the muscle in 24%41. In 1920, Reid also found the nerve entry point for the tensor fasciae latae to be in the middle third of the deep surface of the muscle, and, in 1923, Bryce located the entry point in the proximal third of the deep surface of the tensor fasciae latae muscle42,43. In 1908, Frohse and Fränkel described the nerve supply to the tensor fasciae latae at the midpoint of the posterior border of the muscle44.

The proximal part of the tensor fasciae latae is a vulnerable area for potential lesions to its nerve supply; the anterior approach to the hip joint occurs exactly in this region. The ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery may serve as an important landmark. Clamping, coagulation, ligation, and transection of this artery branch close to the muscle belly may damage the terminal branch of the superior gluteal nerve. Another source of potential injury might be the insertion of retractors and instruments45. The intracapsular, rather than extracapsular, placement of retractors will certainly be advantageous to protect the surrounding soft tissue11.

Further care must be taken during the preparation and broaching of the femur in hip arthroplasty. Insufficient exposure of the femur during broaching might lead to direct damage to fibers of the tensor fasciae latae muscle, including its motor nerve branches45-47. When proximal extension of the anterior approach to the hip joint is necessary, care must also be taken where the nerve branch emerges from the interval between the gluteus medius and minimus muscles (Fig. 2-B). Our cadaver dissections suggest that manipulation at the posterior medial origin of the tensor fasciae latae endangers the nerve.

There is little information in the literature regarding injury to the tensor fasciae latae with respect to the anterior approach to the hip joint, as most studies have concentrated on the gluteus medius and minimus muscles20,46-49. In a cadaver study, van Oldenrijk et al. measured the proportional muscle damage of the tensor fasciae latae relative to the midsubstance cross-sectional area using computerized color detection. The median tensor fasciae latae midsubstance muscle damage was 35% of the cross-sectional area after the direct anterior approach to the hip joint50. Bremer et al. performed a retrospective, comparative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of the direct anterior and the transgluteal approach and found that fatty atrophy of the tensor fasciae latae muscle was similar in both groups46.

Lüdemann et al.51 assessed the muscle trauma in minimal invasive hip arthroplasty involving the direct anterior approach by MRI in twenty-five patients preoperatively and at six months after total hip replacement. Postoperatively, they detected a significant reduction in the cross-sectional area on the involved side postoperatively (29% compared with the noninvolved side and 23% compared with preoperatively; p < 0.001) and increased fatty degeneration of the tensor fasciae latae51. In a cadaver study, Meneghini et al. measured the muscle damage to the tensor fasciae latae with use of the minimally invasive anterior approach compared with the minimally invasive posterior approach45. Tensor fasciae latae muscle damage occurred in all specimens subjected to the anterior approach, with a mean of 31% (range, 18% to 58%).

The tensor fasciae latae surface was mostly damaged in the midsubstance of the muscle, which is exactly the area where the superior gluteal nerve enters the tensor fasciae latae. Damage to the muscle belly of the tensor fasciae latae does not automatically imply damage to the nerve branches, but it does endanger the nerve that is very superficial within the muscle belly (Figs. 2-A and 2-B). Also, tension and force applied to the tensor fasciae latae might be harmful to the nerves in its midsubstance. Terminal nerve branch lesions of the superior gluteal nerve are probably underdiagnosed because they are not always symptomatic. The patient whom we observed having atrophy of the tensor fasciae latae after a primary hip replacement (Fig. 4) with the direct anterior approach had an excellent clinical and functional result identical to the contralateral side, where a modified anterolateral approach had been used previously. The patient noticed merely a cosmetic difference. Markhede and Stener measured the abduction force in two patients who underwent an excision of the tensor fasciae latae for a soft-tissue tumor. Both isometric and isokinetic abduction strength on the affected side were reduced to 62% and 86%, respectively, of the nonaffected side for these patients52. This reduced abduction strength can probably be compensated for in some daily activities; however, electromyography and cadaveric studies have emphasized the tensor fasciae latae as an important thigh flexor during the swing phase and thigh abductor during the mid-stance phase of gait. The tensor fasciae latae balances the weight of the body and the non-weight-bearing lower limb during walking53.

Fig. 4.

A photograph showing the pelvis of a seventy-two-year-old female patient after hip arthroplasty on both sides. A direct anterior approach was performed on the right side in 2012 and a modified Watson-Jones approach was performed in 2007 on the left side. One year after the second surgery, during a routine walking check, atrophy of the tensor fasciae latae muscle was noted. Apart from the cosmetic changes on the right side (indicated by the red arrow), the patient did not report any discomfort on either side.

Although some authors believe that damage to the tensor fasciae latae may not be of functional importance, further clinical outcome studies, gait analyses, and electromyography measurements are necessary to determine the functional implications. We believe that knowing the exact anatomy of the tensor fasciae latae and its nerve supply is important to avoid surgical damage to the nerve.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Department of Anatomy, University of Zürich-Irchel, Zürich, Switzerland

Disclosure: None of the authors received payments or services, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via his or her institution), from a third party in support of any aspect of this work. One or more of the authors, or his or her institution, has had a financial relationship, in the thirty-six months prior to submission of this work, with an entity in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. No author has had any other relationships, or has engaged in any other activities, that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. The complete Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest submitted by authors are always provided with the online version of the article.

References

- 1.Rachbauer F, Kain MSH, Leunig M. The history of the anterior approach to the hip. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009. July;40(3):311-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salter RB, Hansson G, Thompson GH. Innominate osteotomy in the management of residual congenital subluxation of the hip in young adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984. Jan-Feb;182:53-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pemberton PA. Pericapsular osteotomy of the ilium for treatment of congenital subluxation and dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965. January;47:65-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias: technique and preliminary results. 1988. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004. January;418:3-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin DB, Beaulé PE, Matta JM. Safety and efficacy of the extended iliofemoral approach in the treatment of complex fractures of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005. October;87(10):1391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clohisy JC, Zebala LP, Nepple JJ, Pashos G. Combined hip arthroscopy and limited open osteochondroplasty for anterior femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010. July 21;92(8):1697-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwata H, Torii S, Hasegawa Y, Itoh H, Mizuno M, Genda E, Kataoka Y. Indications and results of vascularized pedicle iliac bone graft in avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993. October;295:281-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matta JM, Siebenrock KA, Gautier E, Mehne D, Ganz R. Hip fusion through an anterior approach with the use of a ventral plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997. April;337:129-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brien DAL, Rorabeck CH. The mini-incision direct lateral approach in primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005. December;441:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siguier T, Siguier M, Brumpt B. Mini-incision anterior approach does not increase dislocation rate: a study of 1037 total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004. September;426:164-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matta JM, Shahrdar C, Ferguson T. Single-incision anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty on an orthopaedic table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005. December;441:115-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laude F, Sariali E. [Treatment of FAI via a minimally invasive ventral approach with arthroscopic assistance. Technique and midterm results]. Orthopade. 2009. May;38(5):419-28. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrey BF, Morrey MC. Master techniques in orthopaedic surgery. Relevant surgical exposures. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mast NH, Laude F. Revision total hip arthroplasty performed through the Hueter interval. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011. May;93(Suppl 2):143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore AE, Stringer MD. Iatrogenic femoral nerve injury: a systematic review. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011. October;33(8):649-58. Epub 2011 Feb 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eksioglu F, Uslu M, Gudemez E, Atik OS, Tekdemir I. Reliability of the safe area for the superior gluteal nerve. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003. July;412:111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abitbol JJ, Gendron D, Laurin CA, Beaulieu MA. Gluteal nerve damage following total hip arthroplasty. A prospective analysis. J Arthroplasty. 1990. December;5(4):319-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramesh M, O’Byrne JM, McCarthy N, Jarvis A, Mahalingham K, Cashman WF. Damage to the superior gluteal nerve after the Hardinge approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996. November;78(6):903-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svensson O, Sköld S, Blomgren G. Integrity of the gluteus medius after the transgluteal approach in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1990. March;5(1):57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker AS, Bitounis VC. Abductor function after total hip replacement. An electromyographic and clinical review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989. January;71(1):47-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64(1):17-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenny P, O’Brien CP, Synnott K, Walsh MG. Damage to the superior gluteal nerve after two different approaches to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999. November;81(6):979-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson A. Posterior exposure of the hip joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1950. May;32-B(2):183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs LG, Buxton RA. The course of the superior gluteal nerve in the lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989. September;71(8):1239-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unis DB, Hawkins EJ, Alapatt MF, Benitez CL. Postoperative changes in the tensor fascia lata muscle after using the modified anterolateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013. April;28(4):663-5. Epub 2012 Dec 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ince A, Kemper M, Waschke J, Hendrich C. Minimally invasive anterolateral approach to the hip: risk to the superior gluteal nerve. Acta Orthop. 2007. February;78(1):86-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bos JC, Stoeckart R, Klooswijk AI, van Linge B, Bahadoer R. The surgical anatomy of the superior gluteal nerve and anatomical radiologic bases of the direct lateral approach to the hip. Surg Radiol Anat. 1994;16(3):253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comstock C, Imrie S, Goodman SB. A clinical and radiographic study of the “safe area” using the direct lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1994. October;9(5):527-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siebenrock KA, Rösler KM, Gonzalez E, Ganz R. Intraoperative electromyography of the superior gluteal nerve during lateral approach to the hip for arthroplasty: a prospective study of 12 patients. J Arthroplasty. 2000. October;15(7):867-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frankel A, Booth RE, Jr, Balderston RA, Cohn J, Rothman RH. Complications of trochanteric osteotomy. Long-term implications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993. March;288:209-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavigne P, Loriot de Rouvray TH. [The superior gluteal nerve. Anatomical study of its extrapelvic portion and surgical resolution by trans-gluteal approach]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1994;80(3):188-95. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pérez MM, Llusá M, Ortiz JC, Lorente M, Lopez I, Lazaro A, Pérez A, Götzens V. Superior gluteal nerve: safe area in hip surgery. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004. June;26(3):225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akita K, Sakamoto H, Sato T. The cutaneous branches of the superior gluteal nerve with special reference to the nerve to tensor fascia lata. J Anat. 1992. February;180(Pt 1):105-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavigne M, Ganapathi M, Mottard S, Girard J, Vendittoli PA. Range of motion of large head total hip arthroplasty is greater than 28 mm total hip arthroplasty or hip resurfacing. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011. March;26(3):267-73. Epub 2010 Nov 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duparc F, Thomine JM, Dujardin F, Durand C, Lukaziewicz M, Muller JM, Freger P. Anatomic basis of the transgluteal approach to the hip-joint by anterior hemimyotomy of the gluteus medius. Surg Radiol Anat. 1997;19(2):61-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pascarel X, Dumont D, Nehme B, Dudreuilh JP, Honton JL. [Total hip arthroplasty using the Hardinge approach. Clinical results in 63 cases]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1989;75(2):98-103. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grob K, Monahan R, Gilbey H, Yap F, Filgueira L, Kuster M. Distal extension of the direct anterior approach to the hip poses risk to neurovascular structures: an anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015. January 21;97(2):126-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frohse F. Ueber die Verzweigung der Nerven zu und in den menschlichen Muskeln. Anat Anz. 1898;14:321-43. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisler P. Die Muskeln des stammes. [Muscles of the trunk.] In: von Bardeleben, editor. Handbuch der anatomie des menschen. [Handbook of human anatomy.] Vol. 2 Jena, Germany: Fischer; 1908-1912. German. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brash JC. Neurovascular hila of limb muscles. Edinburgh: E & S Livingstone; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reid RW. Motor points in relation to the surface of the body. J Anat. 1920. July;54(Pt 4):271-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryce TH. Myology. In: Sharpey Schafer E, Symington J, Bryce TH, editors. Quain’s elements of anatomy. 11th ed London: Longmans, Green; 1923. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frohse F, Fränkel M. Die muskeln des menschlichen beines. [The muscles of the human leg.] In: von Bardeleben, editor. Handbuch der anatomie des menschen. [Handbook of human anatomy.] Vol. 2 Jena, Germany: Fischer; 1908-1912. German. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meneghini RM, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Hozack WJ. Muscle damage during MIS total hip arthroplasty: Smith-Petersen versus posterior approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006. December;453:293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bremer AK, Kalberer F, Pfirrmann CWA, Dora C. Soft-tissue changes in hip abductor muscles and tendons after total hip replacement: comparison between the direct anterior and the transgluteal approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011. July;93(7):886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfirrmann CWA, Notzli HP, Dora C, Hodler J, Zanetti M. Abductor tendons and muscles assessed at MR imaging after total hip arthroplasty in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients. Radiology. 2005. June;235(3):969-76. Epub 2005 Apr 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lachiewicz PF. Abductor tendon tears of the hip: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011. July;19(7):385-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Müller M, Tohtz S, Winkler T, Dewey M, Springer I, Perka C. MRI findings of gluteus minimus muscle damage in primary total hip arthroplasty and the influence on clinical outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010. July;130(7):927-35. Epub 2010 Mar 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Oldenrijk J, Hoogland PVJM, Tuijthof GJM, Corveleijn R, Noordenbos TWH, Schafroth MU. Soft tissue damage after minimally invasive THA. Acta Orthop. 2010. December;81(6):696-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lüdemann M, Kreutner J, Haddad D, Kenn W, Rudert M, Nöth U. [MRI-based measurement of muscle damage after minimally invasive hip arthroplasty]. Orthopade. 2012. May;41(5):346-53. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Markhede G, Stener B. Function after removal of various hip and thigh muscles for extirpation of tumors. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981. August;52(4):373-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gottschalk F, Kourosh S, Leveau B. The functional anatomy of tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius and minimus. J Anat. 1989. October;166:179-89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]