With interest we follow the publications that show the presence of putative severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by electron microscopy (EM) in patient tissues and the debate about these results, which should have sufficiently raised attention to their correct interpretation.1, 2

Nevertheless, ultrastructural details in autopsy tissues have been misinterpreted as coronavirus particles in recent papers. Bradley and colleagues3 described “coronavirus-like particles” in autopsy specimens of the “respiratory system, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract”, and in a case report Dolhnikoff and colleagues4 described “viral particles” in “different cell types of cardiac tissue” of a deceased child. However, the images in these publications show putative virus particles that lack sufficient ultrastructure for an unambiguous identification as virus. Some of these particles definitely represent other cellular structures, such as rough endoplasmic reticulum (eg, Dolhnikoff and colleagues,4 figure 3B), multivesicular bodies (Bradley and colleagues,3 figure 5C) and coated vesicles (Bradley and colleagues,3 figure 5B, G). Moreover, it is remarkable that Dolhnikoff and colleagues4 referred to findings, described by Tavazzi and colleagues,5 of “viral particles” in interstitial cells, which are clearly non-viral structures, such as coated vesicles.4, 5 Furthermore, Bradley and colleagues3 quoted publications as a reference for their virus particle identification, which, in our opinion, both identified non-coronavirus structures as coronavirus particles, as already discussed by Goldsmith and colleagues1 and by Miller and Brealey.2

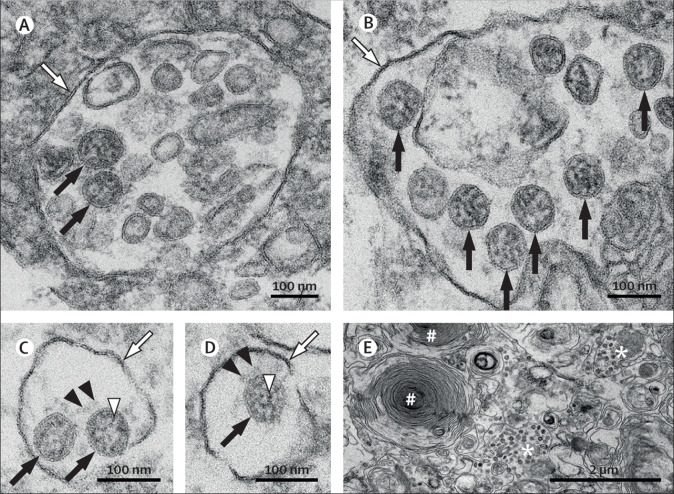

EM is complementary to other techniques used for studying diseases, and it continues to be a valuable tool in certain diagnostic fields. In studies of infectious diseases, EM is considered the gold standard to prove the presence of an infectious unit; in the case of COVID-19 diagnosis, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 particles (figure, A–D ) complements the molecular traces of SARS-CoV-2-specific proteins or nucleic acids. Furthermore, EM allows the exact localisation of viruses in tissues and within cells. This, in turn allows target cells of virus infection to be specified (figure E) and informs about the reproduction of the virus.

Figure.

SARS-CoV-2 ultrastructural morphology in an autopsy lung specimen

Characteristic substructure of SARS-CoV-2 particles at high magnification obtained by electron microscopy (black arrows point to well preserved coronavirus) in an endothelial cell (A) and a type II pneumocyte (B, E). Although characteristic coronavirus morphology might be negatively affected by autolysis of cells, generally complicating cell type assessment, we found these coronavirus particles in a patient with a post-mortem interval of 30 h. Intracellular coronavirus particles are typically located within membrane compartments (A-D; white arrows). A heterogeneous, electron-dense, partly granular interior with ribonucleoprotein can be differentiated (C–D; white arrowheads), envelope membranes of coronavirus are well resolved, and some particles show delicate surface projections (ie, spikes; C–D; black arrowheads). In a type II pneumocyte (E), lamellar bodies are indicated by the # symbol, and compartments with numerous coronavirus particles are indicated by the * symbol. RT-PCR of this lung specimen revealed a high SARS-CoV-2 RNA load. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

As diagnostic EM requires both specialised staff and expensive equipment, and has been replaced by other methods (eg, immunohistochemistry) in several fields of application, its use has been in decline in the past decades, resulting in irreversible loss of expertise that now becomes dramatically overt during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This dilemma of diagnostic EM should alarm us all, as misleading information on the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in tissue has already made its way into the scientific literature and seems to be perpetuated.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Goldsmith CS, Miller SE, Martines RB, Bullock HA, Zaki SR. Electron microscopy of SARS-CoV-2: a challenging task. Lancet. 2020;395:e99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller SE, Brealey JK. Visualization of putative coronavirus in kidney. Kidney Int. 2020;98:231–232. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley BT, Maioli H, Johnston R. Histopathology and ultrastructural findings of fatal COVID-19 infections in Washington State: a case series. Lancet. 2020;396:320–332. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31305-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolhnikoff M, Ferreira Ferranti J, Apericida de Almeida Monteiro R. SARS-CoV-2 in cardiac tissue of a child with COVID-19-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:790–794. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30257-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tavazzi G, Pellegrini C, Maurelli M. Myocardial localisation of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:911–915. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]