In The Lancet, the RECOVERY Collaborative Group1 report the clinical results from the RECOVERY trial—one of the largest and most productive platform trials to date among patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19—on the effectiveness of lopinavir–ritonavir treatment. Compared with the first randomised trial to investigate lopinavir–ritonavir in patients with COVID-19 by Cao and colleagues (including the authors of this Comment),2 the size of the lopinavir–ritonavir group in the RECOVERY trial was much larger and hence provides a more solid evidence base regarding possible lopinavir–ritonavir treatment effects. The trial randomly allocated 5040 patients from 176 UK hospitals (3077 men and 1963 women), and the mean age of study participants was 66·2 years (SD 15·9).1 No differences were observed between patients assigned to lopinavir–ritonavir versus usual care in the primary outcome of 28-day all-cause mortality (rate ratio 1·03, 95% CI 0·91–1·17; p=0·60) or key secondary clinical endpoints, including duration of hospital stay and the proportion of patients discharged alive from hospital. Subgroup analyses did not find evidence for a time-to-treatment effect or benefit in those with less severe illness. The findings of these two open-label studies support each other and conclude that lopinavir–ritonavir is not effective in improving outcomes for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19.

The authors should be commended for the large amount and high quality of work they have accomplished, but a limitation of the pragmatic design of the RECOVERY trial is the lack of virological and biomarker data. In this regard, the previous trial2 in Wuhan, China, did not find evidence that lopinavir–ritonavir reduced viral RNA loads in the upper respiratory tract of patients with COVID-19.2 Furthermore, neither trial collected data on lopinavir exposure levels in treated patients. In any case, the results of these two trials and the similar findings with respect to a lack of mortality reduction in the WHO SOLIDARITY trial,3 as well as the well documented adverse effects and drug interactions caused by lopinavir–ritonavir, have led to updating of clinical management guidelines for COVID-19 to discourage use of lopinavir–ritonavir in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 outside of clinical trials.

At the beginning of the pandemic, approved or investigational drugs with in vitro activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) replication were quickly embraced as treatment options for COVID-19, including antivirals such as lopinavir–ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, and remdesivir.4 Due to the high mortality of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19, severely and critically ill patients were the main target population in initial clinical trials. Unfortunately, none of these antiviral drugs have proved effective in significantly reducing mortality, although further results are awaited for remdesivir.4 Animal models can be helpful in down selection of candidate antivirals for study and notably have confirmed the in vivo antiviral activity of remdesivir, but not of lopinavir–ritonavir or hydroxychloroquine.5

Is there a role of early antiviral treatment for mild cases of COVID-19 or prophylaxis in high-risk populations after exposure? We think the answer is yes. Given the efficient replication of SARS-CoV-2 shortly after infection6 and the association between mortality and viral RNA loads at diagnosis,7 it is possible that early use of sufficiently potent antiviral drugs would be an important determining factor in clinical outcomes, although few early intervention trials have been completed. Although trials of prophylaxis and early treatment with hydroxychloroquine have yielded essentially negative findings,8, 9 recent reports indicate that treatment with injected or inhaled recombinant interferon beta,10, 11 or with a human neutralising monoclonal antibody directed to the S protein anti-receptor binding domain,12 can reduce viral replication and the risk of disease progression in patients with earlier stages of illness.

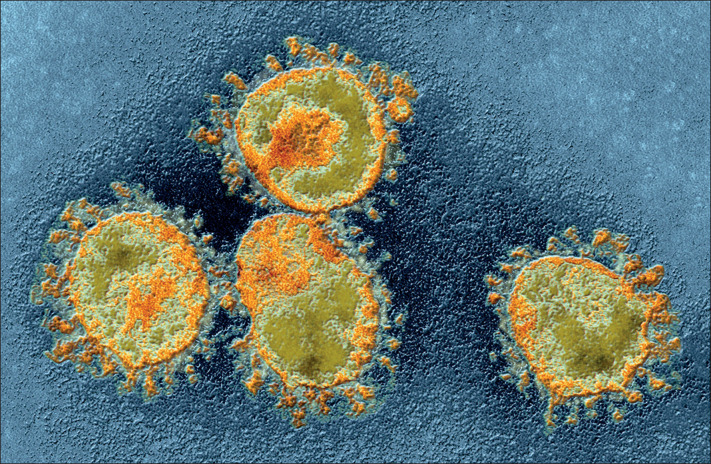

© 2020 Ami Images/Science Photo Library

The relative contributions of viral replication and dysregulated host immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection at different stages of COVID-19 are incompletely understood, and the extent and kinetics of viral replication in the lungs and other organs of patients with COVID-19 are not well characterised, although high sputum viral RNA levels are often found in patients admitted to hospital.13 The RECOVERY trial findings of reduced mortality with dexamethasone treatment without concurrent antiviral therapy in individuals with severe or critical COVID-19 establish the importance of immunopathological host responses in such patients.14 Perhaps viral sepsis would be a more accurate term to describe the clinical manifestations of severe or critically ill patients with COVID-19.15 As preliminarily reported for trials of remdesivir and the JAK inhibitor baricitinib,16 or the anti-interleukin-6 inhibitor tocilizumab,17 combination therapy with antivirals and immunomodulators is an obvious strategy to improve outcomes in more seriously ill patients with COVID-19.

In conclusion, early use of easily administered, more potent antivirals to treat outpatients and prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 needs further clinical study. However, antiviral monotherapy for moderately to severely ill patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 might not be enough. The evaluation of efficacy and safety of combination therapy with antivirals and immunomodulators for severe COVID-19 should be a priority for ongoing and future clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

BC has worked closely with Article author Peter Horby on influenza and COVID-19 therapeutic studies. FGH reports personal fees from University of Alabama Antiviral Drug Discovery and Development Consortium and Wellcome Trust, outside the area of work discussed here, and has been a non-compensated consultant to companies developing therapeutics or vaccines for COVID-19 or Middle East respiratory syndrome, including Arcturus, Cidara, Fujifilm, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Merck, Pardes Biosciences, Regeneron, resTORbio, Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, SAB Biotherapeutics, Takeda, and Vir. FGH is a member of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board for a clinical trial funded by Cytodyn, Inc, with fees paid to the University of Virginia School of Medicine. FGH has been a collaborator and co-author on publications with several authors of the Article discussed here.

References

- 1.RECOVERY Collaborative Group Lopinavir–ritonavir in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32013-4. published online Oct 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO WHO discontinues hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir treatment arms for COVID-19. July 4, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/04-07-2020-who-discontinues-hydroxychloroquine-and-lopinavir-ritonavir-treatment-arms-for-covid-19

- 4.Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, Ge L. Drug treatments for covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson BN, Feldmann F, Schwarz B. Clinical benefit of remdesivir in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;585:273–276. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pujadas E, Chaudhry F, McBride R. SARS-CoV-2 viral load predicts COVID-19 mortality. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e70. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30354-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulware DR, Pullen MF, Bangdiwala AS. A randomized trial of hydroxychloroquine as postexposure prophylaxis for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:517–525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2016638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skipper CP, Pastick KA, Engen NW. Hydroxychloroquine in nonhospitalized adults with early COVID-19: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-4207. published online July 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung IF-N, Lung K-C, Tso EY-K. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Synairgen Synairgen announces positive results from trial of SNG001 in hospitalised COVID-19 patients. July 20, 2020. https://www.synairgen.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/200720-Synairgen-announces-positive-results-from-trial-of-SNG001-in-hospitalised-COVID-19-patients.pdf

- 12.Eli Lilly and Company Lilly announces proof of concept data for neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in the COVID-19 outpatient setting. Sept 16, 2020. https://investor.lilly.com/node/43721/pdf

- 13.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The RECOVERY Collaborative Group Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. published online July 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Liu L, Zhang D. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet. 2020;395:1517–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eli Lilly and Company Baricitinib in combination with remdesivir reduces time to recovery in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in NIAID-sponsored ACTT-2 trial. Sept 14, 2020. https://investor.lilly.com/node/43706/pdf

- 17.Business Wire Genentech's phase 3 EMPACTA study showed actemra reduced the likelihood of needing mechanical ventilation in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia. Sept 18, 2020. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200917006062/en/Genentech's-Phase-III-EMPACTA-Study-Showed-Actemra-Reduced-the-Likelihood-of-Needing-Mechanical-Ventilation-in-Hospitalized-Patients-With-COVID-19-Associated-Pneumonia