Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a far-reaching negative impact on healthcare systems worldwide and has placed healthcare providers under immense physiological and psychological pressures.

Objective

The aim of current study was to undertake an in-depth exploration of the experiences of health-care staff working during the COVID-19 crisis.

Methods

Using a thematic analysis approach, a qualitative study was conducted using semi-structured interviews with 97 health care professionals. Participants were health care professionals including pre-hospital emergency services (EMS), physicians, nurses, pharmacists, laboratory personnel, radiology technicians, hospital managers and managers in the ministry of health who work directly or indirectly with COVID-19 cases.

Results

Data analysis highlighted four main themes, namely: ‘Working in the pandemic era’, ‘Changes in personal life and enhanced negative affect’, ‘Gaining experience, normalization and adaptation to the pandemic’ and ‘Mental Health Considerations’ which indicated that mental ill deteriorations unfolded through a stage-wise process as the pandemic unfolded.

Conclusions

Participants experienced a wide range of emotions and development during the unfolding of the pandemic. Providing mental health aid should thus be an essential part of services for healthcare providers during the pandemic. Based on our results the aid should be focused on the various stages and should be individual-centred. Such interventions are crucial to sustain workers in their ability to cope throughout the duration of the pandemic.

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Health personnel, Adaptation, Psychological, Mental health, Qualitative

INTRODUCTION

Covid-19 has been the first respiratory pandemic since the 1918 Influenza which has had a widespread global effect. It has had severe economic, social, political and cultural consequences on human life and these consequences will be experienced well into the future. The emergence of this pandemic has been a massive test for health-care systems in terms of their capabilities and weaknesses. A crucial effect of this pandemic has been its’ impact on staff mental health 1. The high mortality rate, high disease transmission capacity, and the shortcomings of health systems 2 have had a significant impact on the mental health of employees, and these effects are ongoing 3. In addition, there is a fear that there will be no cure or vaccine for the disease in the near future, which will exacerbate the negative effects on staff physical and mental health and performance. Every wave of the disease may have the same or even exacerbated effects as stressor effects compound over time. While mitigation thorough flattening the curve and raising the line is the main strategy in the control of the pandemic 4, decreases in healthcare capacity due to poor mental health and frustrations of health care providers can cause significant problems, especially if and when resurgences occurs.

The first cases of COVID-19 in Iran were reported on February 19 and the number of new cases and deaths has increased exponentially since then 5 , 6. During the first months of the outbreak, healthcare-providers were exposed to a variety of new and unprecedented events and experienced a range of feelings in response to such events. While the visible expression of their feelings and emotions were largely hidden behind masks, deleterious unprecedented events, high work pressure and little attention paid to psychological aspects have had devastating effects on staff mental health. Since health-care providers’ lived experiences during the COVID-19 crisis was the only way to understand what they went through 7 , 8 we conducted the current study utilizing a qualitative approach. The aim of the study was to undertake an in-depth exploration of the experiences and the mental health consequences of health-care staff working during the COVID-19 crisis.

METHODS

Research design

We conducted a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with health care professionals during the COVID-19 crisis. Interviews were conducted using telephone and video calls from March 10 to July 4. We used thematic analysis which is one of the most common forms of qualitative data analysis9. The emphasis of thematic analysis was on identifying, analysing and interpreting patterns of meaning within qualitative data. Such a method allowed for a rich in-depth exploration of participants experiences. We recruited the study participants through maximum variation sampling. The main variation variables were age, marital status, work experience, medical specialties and seniority.

Participants

The participants were recruited from three major cities in Iran that were the main hotspots at the time including Tehran, Qom and Rasht. The inclusion criteria were being a health care professional including pre-hospital emergency services (EMS), physicians, nurses, pharmacists, laboratory personnel, radiology technicians, hospital managers and managers in the ministry of health who work directly or indirectly with COVID-19 cases. Healthcare providers who met the inclusion criteria were approached based on the analysis. All people who were approached agreed to participate in the study. A maximum variation sampling strategy was chosen to allow the capture all groups’ experience. Participants were approached in the different units based on age, marital status, work experience, medical specialties and seniority. Data gathering and analysis was concurrent with each other to determine when saturation was achieved, that is, when no new data was emerged and all identified themes where sufficiently supported by the data collected.

Data collection

The main method of data gathering was semi-structured, in-depth interviews. Ninety-seven interviews with eighty-six participants were conducted. …, …., …. and …. conducted the interviews. Interviewers (three male and one female) were faculty members (PhD) who were experts in the conduction of qualitative studies. Demographic information of study participants was obtained before the interview. Ten interviews were conducted one month after the original interviews to assess the changes in the experience of participants. The interviews consisted of three main parts based on a guideline introduced by Charmaz 201410namely: opening, intermediate and ending questions. Examples of opening questions included “What did you experience during COVID-19 pandemic” and “What changes did you experience in your work or private life?”. In the main part of the interview, the actions, feelings, and thoughts of health-care providers were examined. Questions such as “What did you feel when you taking care of patients with COVID-19?”, “How did the pandemic change your life?”, “How did your feeling change over time?”, “What was the hardest part of work during pandemic?”, “What changes in your mental status did you feel?”, and “What do you think about the consequences of working in this pandemic?” were used in the intermediate part of the interview. Follow-up questions were asked after each participant's responses in order to engage them in a dialogue. At the end of the interview, the participants were asked if they had anything to add. Interviews last between 34 to 61 minutes. The study design and reporting were according to Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ).

Data analysis

The method that was introduced by Braun 2006 was used9. The written transcripts of the interviews were prepared immediately following the interviews. Each and all interviews were reviewed by the entire group of interviewers for accuracy. All interviewers listened the voice recordings and checked it with the transcribed text. Transcribed interviews were sent to interviewees to check for accuracy. To become immersed in the texts and to fully understand them, the transcripts were read from start to the end, several times by the corresponding author and interviewers. When interviewers had read the text carefully and extracted important statements, they labelled each statement with a code. …., ….., ….. and …. analysed the data. …. translated codes and quotations into English and these were further reviewed by ….. in addition, the codes were discussed in virtual meetings by all authors. Similar codes and ones that created a pattern were summarized into themes. Continuous comparison of codes and categories and re-categorization were carried out during the study in virtual meetings with research team members. The results of the study were presented to six participants of the study who agreed with the main observed patterns. Thick description of the methods and representative equations were used to increase transferability. Microsoft® Excel was used in analysing the data.

Ethical review

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Omitted for review (…). An email link to a form with the study objectives and an informed consent were sent to each participant which was signed electronically. The voluntary and confidential nature of the study was explained to participants before each interview and consent was obtained for recording of interview and transcriptions.

RESULTS

The mean (SD) of age and work experience of study participants were 35.34 (6.90) and 10.04 (6.08) years, respectively. Forty-four participants (51.2%) were male. Sixty-one participants (70.9%) were married. The COVID status of participants was 23 (26.7%), 16 (18.6%) and 47 (54.7), respectively, positive, negative and unknown. Thirty-six (41.9%) nurses, seventeen (19.8%) managers, nineteen (22.1%) physicians, eight (9.3%) EMS personnel, two (2.3%) pharmacists, two radiologists and two lab technicians participated in the study.

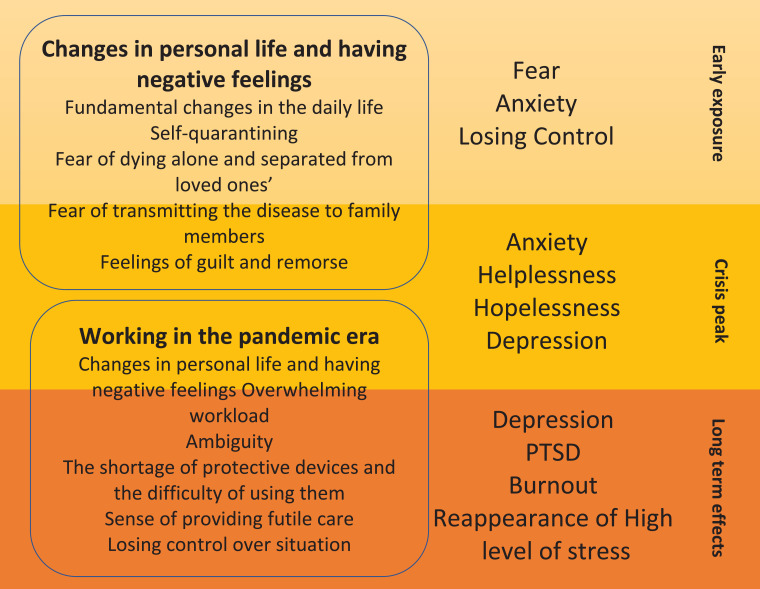

Three main themes emerged from data, namely: Working in the ‘pandemic era’, Changes in personal life and enhanced negative affect, Gaining experience, normalization and adaptation to the pandemic. A further category that emerged was Mental health considerations. The results of the study are presented in Figure 1 as a model. The model consisted of three level including Early exposure, crisis peak and long-term effects. The first two themes, that is: Working in the pandemic era and Changes in personal life and enhanced negative affect contributed to the mental ill health and needs of healthcare providers during COVID-19 crisis.

Figure 1.

The three-level model of mental health considerations for healthcare providers

WORKING IN THE PANDEMIC ERA

A key aspect of this theme was the experience of inordinately high levels of workload and feelings of losing control over the situation. Subthemes along with related codes and quotations are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Subthemes, code and related Quotations of the Working in the pandemic era theme

| Sub-themes | Codes | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Overwhelming workload | Heavy workload Fast changes in the workplace Unprecedented workload |

In the early days, our workload was very high, we had to move the wards and hospitalized corona patients in the non-infectious wards (Nurse) Early in the pandemic, I was so tired and I thought I hadn't ever experienced such a lot of work (Physician) |

| Ambiguity | Changes in protocols Changes in guideline Advising of new drugs You do not know what works and what does not work Disapproval of new drugs Rapid changes in patients' status |

Every day a new drug is introduced, every day a new route of transmission is introduced (Physician) Health organizations first said that the only way to transmit the disease was through droplets. Then they said it could be transmitted through aerosols. They are now telling that it can be transmitted by oral-fecal method (Nurse) As a doctor, we usually feel that we can control the disease, but it gets worse very quickly and there is no cure for it (Physician) The patients were coming today, they were fine, they were dying the next day, young, old, we didn't know what to do at all (Physician) |

| Losing control over situation | Losing control Feeling helpless Ineffectiveness of routine treatments Depletion of existing human resources Inadequacy of previous work experiences |

This disease does not have a specific drug, nor can you predict with confidence who will survive and who will die. This made me feel (completely ineffectual and I felt) like I was losing control (Physician) Our patients (in the past) usually do not die, they are treated with antibiotics, but here (with this disease) it was different and we could not do anything (Physician) Some of the staff had panic symptoms, they were crying and scared. Some of them who had an underlying condition or were taking corticosteroids had to go home and pressure was added to the rest of the staff (Hospital Manager) |

| The shortage of protective devices and the difficulty of using them | Shortage in protective devices Difficulty of usage for long periods |

It's very difficult to wear N95 masks for twelve hours, I feel short of breath and I will definitely have problems later (Nurse) They give (you) a body suit in each shift. When we wear these clothes, sweat flows from all over our bodies, we can't eat anything with these clothes, we can't drink anything too, we have to wear them for 12 hours (Nurse) |

| Sense of providing futile care | Disease has no definite cure Patients die despite hard work Feelings of pointlessness |

There is no cure for this disease, usually patients who are transferred to an intensive care unit do not have much chance. As for this disease, I feel that our work does not have much effect on patients' recovery (Physician) When our patients die after all this hard work, with these protective clothes that are so difficult to wear, we say to ourselves, what is the point of our work? (Nurse) |

| A sense of conscientiousness and self-sacrifice |

Being loyal to the medical oath Self-sacrifice Preparing to give live for others Risking their health for others |

It is our duty to work in these situations, our work requires it (Physician) Every job has its difficulties and difficult situations. This is the difficult situation of our work (Nurse) We have to follow the medical oath we took, based on that oath, it is our duty to be at work now (physician) When we came into this profession, we prepared ourselves that we might even lose our lives. This is the sacrifice that a nurse makes (Nurse) It is our duty, and god will reward us with the best (Nurse) |

Overwhelming workload

Eighty-seven percent of the participants said that the workload experienced in the first days of the pandemic was overwhelming. This overwhelming workload manifested in a very high volume of patients, the difficulty of using protective equipment, an ever-increasing number of severe cases and high mortality rates.

Ambiguity

Among the participants, 73.80% believed that they had received contradictory information from scientific sources. Also, 80.85% expressed dissatisfaction with the frequent change of protocols, prevention and treatment methods and the attendant negative effects of this on their performance. Compounding this ambiguity was an inability to successfully treat patients, and the unpredictable and sudden course of the disease.

Losing control over situation

A total of 70.23% of participants experienced feeling a loss of control and loss of confidence in relation to their current situation. This experience of loss of control was especially evident amongst physicians with all interviewed physicians emphasizing a sense of losing of control over the patient's situation and treatment in the early days of the pandemic. They noted that pre-COVID, except in very severe cases, infectious diseases alone did not cause the death of their patients. However, this disease had exacted a ravaging effect on patients, inducing a sense of helplessness within them. The large number of clients, the high rate of hospitalizations, the high mortality rate, and the fact that there was nothing that they could do to save these patients, escalated their sense of losing of control.

The shortage of protective devices and the difficulty of using them

The shortage of protective devices and the difficulty of using them were reported by all participants. The scarcity of N95 masks, protective clothing, gloves, shields and gowns was stated by all interviewees, with most of them noting the extreme discomfort of using the protective gear. This suggested that the health care system was not adequately resourced and the usual protective procedures and guidelines to meet the special conditions of a pandemic could not be adequately or comfortably adhered to.

Sense of providing futile care

Some participants believed that their inability to treat large numbers of patients gave them a sense of engaging in ‘futile’ care. This feeling was especially evident among nurses in the intensive care units. 73.80% of the participants believed that their care was almost pointless, especially in instances where patients died despite all their interventions.

A sense of conscientiousness and self-sacrifice

In spite of all the negative experiences endured, another sub-theme that emerged was that of conscientiousness and self-sacrifice. Over the last 10 years, there has been an ever-increasing shortage of healthcare workers, which has been exacerbated by the country's economic sanctions. In addition, at the time, a number of workers were unable to work given that they had comorbid conditions and they therefore withdrew from work during the pandemic. Thus, this staff absence contributed further to employee shortages. In this context, while the majority of staff tried to work longer hours and extra shifts to make up for the shortfall, the health care system was unable to afford to pay extra money and provide protective facilities and these staff were therefore not reimbursed for their extra effort. Yet they noted that in spite of all of this hardship, their professional duty to 'rasing the line', a commitment to their medical oath, the notion of self-sacrifice and religious considerations compelled them to carry on. Among the participants, 61.90% believed that their professional duty in the current situation was to come to work and do their job. Almost thirty-seven percent (36.90%) of the participants directly declared that their commitment to their medical oath was one of the main reasons for doing their duties in the pandemic situation. Further, among the participants, 17.85 percent said that they had come to work out of a sense of self-sacrifice and religious obligation, that is, for God's sake.

CHANGES IN PERSONAL LIFE AND ENHANCED NEGATIVE AFFECT

The COVID-19 pandemic induced fundamental changes in the life of study participants. It also led to them experiencing a wide range of negative emotions. Subthemes along with related codes and quotations of this theme are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Subthemes, code and related Quotations of the Changes in personal life and enhanced negative affect theme

| Sub-themes | Codes | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental changes in the daily life |

Changes in the way we live Impaired relationships with loved ones |

I did not kiss my children and my husband from the beginning of this disease, my husband's and I are sleeping in separate places (Nurse) I have a two-year-old boy who constantly wants to hug and kiss me, and I miss him very much (Nurse) |

| Self-quarantining |

Living separately Living alone Changing living place and space |

I separated my space in the house, I just went to a room, my food was also separate, I washed my hands regularly (Physician) After realizing that my test was positive, I prepared another house and lived completely separately (Manager) The hospital provide a hotel for us, I did not see my family for weeks (Nurse) |

| Fear of dying alone and separated from loved ones’ |

Being separted Fear of dying alone Fear of not having religious rites and ceremonies |

When I was hospitalized in the ICU, I had very severe shortness of breath. When the shortness of breath was present, I thought I was dying (Nurse) I was thinking, I will die alone, without seeing my family, they will not see my body. I will not have a proper funeral (Nurse) |

| Fear of transmitting the disease to family members |

Fear of transmitting the disease to family members Unreliable and inadequate tests |

My biggest fear is that I will be an asymptomatic carrier and pass the disease on to my family members. My own parents or the parents of my husband, my children, or anyone else who may have an underlying disease (Laboratory Technician) It is also possible to transmit the disease to family members without repeated testing. The test also has a lot of false negatives and it take a lot of time to receive the results (EMS Personnel) |

| Feelings of guilt and remorse |

Self-blaming Considering oneself as the cause of another's death Feeling guilty |

My husband got the disease from me and he died and I will never forgive myself. If my job was something else, my husband would not have died (Nurse) I had mild symptoms, yet my father got the disease from me and he died, and I couldn't do anything about it. I caused his death (Nurse) |

Fundamental changes in the daily life

All participants in the study believed that with the onset of the disease, their lives had changed fundamentally, and 95.23 percent believed that they would probably never return to normal. These changes included social interactions, family relationships, and work life. One of the results of these fundamental changes in daily life was a significant reduction in emotional relationships and the experience of sensory deprivation. In this regard participants felt that they were prisoners in isolation under enforced separation from their families.

Self-quarantining

Due to the uncertainty about the nature of the disease, its’ high transmission rate, and the fear of being an asymptomatic carrier and thereby transmitting the disease to others; 96.42 percent of the participants had completely separated themselves from their family. In all cases, the level of relationship and engagement between the individual and the family was dramatically and suddenly reduced.

Fear of transmitting the disease to family members

The fear of being a carrier and transmitting the disease to the family members was the biggest concern of all participants and was conveyed by all participants.

Fear of dying alone and separated from loved ones

Among participants, 76.19 percent said they feared they would become ill, and die alone while separated from their families. In addition, the fear of being buried without traditional religious ceremonies was also experienced. These fears were intensified for healthcare providers who had tested positive, with their first fear being transmission of COVID-19 to their family followed by fears about their own death in isolation and burial without religious rites and ceremonies.

Feelings of guilt and remorse

80.95% of the interviewees stated that they would blame themselves if something happened to one of their family members. Eight members of the health care team who were interviewed and lost a family member because of COVID-19 blamed themselves and felt immense remorse and guilt. Although, a nurse whose husband died of the virus lost much of her sense of guilt after her PCR test turned out to be negative and she was able to attribute his infection to alternative exposure, many others still blamed themselves.

GAINING EXPERIENCE, NORMALIZATION AND ADAPTATION TO THE PANDEMIC

The third theme was gaining experience, normalization, and adaptation to the pandemic. This theme represented the growth and development of participants over time. Participants interviewed at the end of the study and those interviewed again after a one-month period stated that they had regained their confidence. This process was the result of overcoming the initial crisis, gaining experience with regard to patient management, reducing referrals and increasing recoveries. Under these circumstances, the pandemic situation had become “normal life” for healthcare providers. However, this adaptation to the pandemic was still accompanied by worries about the future and, for some, eventual ‘pandemic fatigue’ had begun to set in. Subthemes along with related codes and quotations for this theme are presented in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Subthemes, code and related Quotations of the Gaining experience, normalization and adaptation to the pandemic theme

| Sub-themes | Codes | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Gaining experience | Being able to distinguish between COVID and non-COVID patients Gaining treatment knowledge and skills |

We recognized the effects of drugs, we were able to differentiate infected patients from other infections, and we were able to identify more effective drugs (Physician) Gradually, we learned to manage patients and we obtained better results (Physician) Now, I know how to manage the ventilator and what technique of breathing is more effective (Nurse) |

| Regaining of self-confidence | Regaining control Restoration of self-confidence |

Now our work is on track, patients are dying less, we know the drugs, control is back (Physician) It was a constructive experience, both for myself and my assistants, our experience growth was equal to several years and now we (now feel able to) work with confidence (Physician) |

| The normalization of life | Learning to live with the disease and using protective measures as a new way of life |

This disease has become like any other diseases for us, we take more care of ourselves, but we are less afraid and we are working with it (Nurse) Living like this has now become a normal part of our lives, regular disinfection, social isolation or distancing, they are normal now. We have (learnt) to live this way (Physician) |

| Adaptation to the pandemic | Getting used to this kind of living Becoming new life style |

We are used to this situation. We always take the necessary precautions at work. We also use them at home and outside. The fear I had at first has diminished (Nurse) It seems we have to get used to this lifestyle. Wearing a mask all the time, washing our hands regularly, reducing social interactions are new lifestyles. We have completely forgotten about shaking hands (Physician) |

| Worries about the future | Being worried about financial issues, mental health issues and the duration of the pandemic |

Hospital revenues came from hospitalization of patients with other diseases. All hospitals are now dedicated to Corona. The hospitalization of patients with Corona, derives no income and its' costs are many times higher. We are worried about future payments to our personnel (Hospital Manager) If this disease last very long, we will have seriouse problems, especially in the mental health area, people including us need to have human relationships, we can not work like robots for a long time (Nurse) |

| Pandemic Fatigue | Becoming Tired Wanting to be rid of fear Let's get this over and done with |

I'm tired of going home every day with fear of transmitting the infection to my family. If we're going to get infected, it's better to be early (Physician) Using protective equipment has become very difficult, I don't think I will be able to continue in the long run, some day I will give up (Nurse) |

Gaining experience

Among participants, 92.85% believed that they had gained experience in managing patients over time. This rate was 100 percent among physicians, and all of 10 participants who were interviewed again after one-month believed they had gained enough experience to adequately manage patients.

Regaining of self-confidence

All physicians and 84.52 percent of nurses stated that, through experience with successful patient management, they had regained their self-confidence.

The normalization of life

Of the participants, 86.90% said that after the early stages, living and working in new conditions and adoption of new routines had become almost normal for them.

Adaptation to the pandemic

All participants who were re-interviewed and participants in the final stages stated that they had adapted to the pandemic situation. Adaptations included learning protective techniques, coping with isolation and social distancing and reducing their fear of illness. Due to the fact that there is no definite end for this pandemic, the healthcare providers had prepared themselves for long-term living under pandemic conditions by taking the necessary precautions. Among the participants, 89.28% stated that they had adapted to living under these conditions.

Worries about the future

However, 82.14% of participants still had a pervasive sense of worry for the future. This worry included concerns about themselves, their immediate family and relatives and their future economic status. There were also concerns about the neglect and loss of patients to other diseases.

Giving up protection measures

In the later interviews we found that some participants were very tired of using protective measures and they were not as vigilant with these measures. Some of our participants stated that they were exhausted by the continuous fear and over-vigilance and had started to relax their standards somewhat when it came to the donning of protective gear.

MENTAL HEALTH CONSIDERATIONS

The considerations related to the mental health of healthcare providers emerged as a category. Experiences of loss of control, heavy workload, severe stress, the experience of a sense of futile care, fear of infection and transmission, self-isolation and quarantine, decreased emotional relationships, fundamental changes in lifestyle, worrying about the future and the economic situation, all appeared to contribute towards the manifestation of mental health issues. Mental health problems varied depending on the stage of the pandemic crisis and the individual. Therefore, we extracted two main categories within mental health considerations, including a stage-wise approach and individual-centered considerations. Subcategories along with related codes and quotations are presented in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Subthemes, code and related Quotations of the Mental Health Considerations theme

| Sub-themes | Codes | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Stage-wise approach |

Early exposure High level of anxiety and fear and powerlessness Impaired communication with colleagues and family Losing control |

I was very anxious; I was afraid of getting infected and dying (Nurse) I thought there was nothing I could do; it didn't matter if I was there or not (Physician) We are not used to this kind of work and life. Our communication at work has decreased a lot, and not seeing relatives has a very negative effect (Nurse) |

|

Crisis peak Futility Helplessness Hopelessness High level of losing control Frustrataion Physically and emotionally exhausted |

The number of patients who die is much higher than what we are used to in the ward. Our patients usually do not die (Nurse) When I see my efforts making no difference, I feel more tired, it became exhausting (Physician) Some days I cry for an hour after the shift. It is really depressing to see patients die while you did a lot to help them (Nurse) |

|

|

Long term effects Persistent fear of getting infected Symptoms of Post-traumatic stress disorder Feeling sad Reactivation of earlier fears as patient numbers resurge |

Although we are used to working in this situation, we are still worried about getting the infection and transmitting it to our family members (Physician) Some nights I have nightmares, I see that my patients are dying and I have done nothing (Nurse) I'm still not feeling well and I feel very sad. Why did this happen and (why did) this disease killed so many people? (Nurse) Some nurses cried when the number of patients rose again, working with recurring level of stress is very hard (Manger) |

|

| Individual-centered considerations |

Personal differences People have abilities Some people are more sensitive Some people need a lot of counseling and support |

Personnel are different. Some are stronger and have more experience. We had a nurse who cried and said she was afraid to enter the ward. We also had a nurse who volunteered to work (taking on extra workload) instead of others (Hospital Manager) Novice and inexperienced employees were very scared. Employees who couldn't find a place for their children to stay away from for a while have (major worries and) stress for their children (Hospital manager) After this, I have to be on leave for a while so that I can return to this job. I have to be very far from the hospital, illness and death (Nurse) Some personnel suffered panic attacks. They couldn't come to work. Some were depressed by the death of their patients. Some still can't adapt (Physician) |

Stage-wise approach

We identified three stages in terms of the manifestation of mental health problems during the coronavirus pandemic crisis. The first stage manifested itself at the onset of the pandemic with fear, anxiety, and a sense of hopelessness and helplessness among healthcare providers. In the first month of the pandemic, extreme fear and anxiety were predominant emotions. At this stage, ambiguity, losing control over the situation and the decline in human interactions, especially in the workplace, increased healthcare providers’ anxiety.

The second stage was accompanied by the high hospitalization of patients, the high patient mortality rate, and the sense of helplessness and sense of providing futile care felt amongst providers in response to these events. In addition, with prolonged self-quarantine and decreased emotional relationships, healthcare providers had begun to show signs of depression. Further, the deaths of large numbers of patients caused healthcare providers to feel frustrated and physically and emotionally exhausted.

In the final mental health stage, that is, in the later stages of the pandemic, healthcare workers started to adapt to pandemic working conditions, but their fears and concerns still lingered. Being worried about patients with other diseases, their own personal future financial problems, having to continue to live in their sensory prisons, and stress due to a lot of patients still dying were acknowledged. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression were the main mental health concerns evidenced at this stage. Evidence of PTSD symptoms became apparent during follow up interviews that were conducted. In this regard, as patient numbers resurged, participants re-experienced earlier stages of panic, fear and helplessness, indicating that just as they thought ‘things were getting under control’ a resurgence occured and they were ‘back to the beginning again’. In this manner it may have been possible that healthcare workers relived the early stages of the cycle of mental ill-health, which may have compounded the stress they had experienced over time. This ‘reliving’ may also have, to some extent. undone the efficacy of some of the coping mechanisms that they had already adopted.

There was also evidence that over time participants, despite their scientific knowledge, were entering into a stage of burnout or ‘pandemic fatigue’ with many expressing that they simply wanted to get back to their ‘normal pre-COVID’ lives (See Table 3). It became evident from participant's comments here that while they may have adapted to this way of life there were lingering future fears, for example, not being paid due to losses in hospital revenues, and thereby, fearing for their economic future. In addition, a sense of loss that the new way of living implied with regard to their social and familial relationships in many instances left them feeling depressed. Further, they noted the experience of recurrent nightmares and replaying of patients dying, which were typical features of post-traumatic stress disorder.

In some instances, reactivation of early fears and panic with patient number resurgences and an overall weariness and pandemic fatigue expressed itself in a desire to abandon the new normal protocols and ‘pretend’ they could go back to their pre-COVID lifestyle.

Individual-centered considerations

In dealing with mental health problems, according to participants, especially those who were hospital and ward managers, future interventions should be individual-centered. That is, interventions should not be generic but should rather be tailor-made to an individual's unique situation and characteristics Depending on the individual's personality, the amount of stress that he/she can endure, the individual's sources of available support, their work motivation, their sense of control, and the experience that the individual has accrued from previous situations and crises; this can all produce variations in individuals’ abilities to currently cope and thereby the level of intervention that they would require. Management and planning for mental health issues should be thus be individual-centered. While all participants expressed variations in the degree of their mental health disturbances, they all acknowledged that they would need time to recover.

DISCUSSION

The results of our study showed high level of stress, fear and anxiety among healthcare providers in the early phases of the pandemic. The sense of helplessness, hopelessness and becoming powerless was prevalent among them. Many expressed fears that they had lost control over the situation and their previous knowledge and skills could not help them in this crisis. They were also worried about their health and their family's health, especially those who had relatives who were old or sick. However, despite these fears, participants continued to work, although they were forced to quarantine themselves and were unable to see their relatives for long periods of time. Although, over time, there was some improvement in work conditions and a degree of adaptation, with the onset of a new wave of disease, initial fears and anxieties resurfaced.

Our results were consistent with previous studies, namely, a review that showed that COVID-19 had significant adverse mental health consequences 11 and an additional study that showed high prevalence of mental health issues in Chinese medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic 12. Similarly, and aligned with our results, all surgery residents in a study conducted in the US expressed concerns about the health of their family, worries about transmitting COVID-19 to their family members and their patients 13.

In line with our results, the results of another study, conducted in….. showed several factors including access to and trust in personal protective equipment, and a desire to deliver good patient care influenced ability and willingness of healthcare workers to follow infection prevention and control guidelines when managing respiratory infectious diseases 14.

Results of a study on nurses in Pakistan showed that while there were negative emotions during working during pandemic some growth was evident in terms of affection and gratefulness, development of professional responsibility, and self-reflection 15. The presence of both negative and positive feelings were also found in another study 16. The findings of both these studies aligned to the findings in our study.

The changes in psychological characteristics of over time were also shown in previous study on nurses in China17. The results of a study on healthcare providers in China showed that intensive work drained health-care providers physically and emotionally but they these providers demonstrated resilience and a spirit of professional dedication to overcome difficulties 18.

Our results showed that there were excessive work demands accompanied by lack of work resources and losing control over work situation. It was also noted that failure to successfully treat patients and the sense of providing futile care in this context could increase the moral distress amongst personnel which has been shown in previous research to be related to burnout and intention to leave (Omitted for Review).

The conditions under which staff were working and the resultant outcomes were framed within the context of the widely used theoretical models of the Job Demands-Resources Model and the Job Demands-Control Model 19 , 20. Both models essentially propose that individuals’ working in environments with excessive demands, lack of resources, and lack of control over their work processes may experience extremes distress which manifests in mental health issues such as exhaustion, burnout and depression. These frameworks were clearly represented the state of healthcare workers’ working environment in the current study, as they toiled under excessive workload, a lack of protective resources and a lack of supportive interactions between colleagues, an inability to control the situation with regard to infection rates, hospital admissions and patient care as it unfolded during the pandemic, and the resultant deleterious impact on staff mental wellbeing.

Limitations

Although our study provided some interesting insights it was not without limitations. The main limitation of our study was that we could not interview healthcare providers in rural areas. Because most of the hospitals in rural area do not have a sufficient number of ventilators, most patients were referred to the big hospitals in the city. However, the risk of transmission and lack of resources remains a common problem in healthcare facilities all around the country and future research needs to examine the experiences of healthcare workers within rural hospitals as well.

CONCLUSIONS

The COVID-19 pandemic has not been the first global pandemic disease in current times While earlier generations experienced the Spanish influenza in 1918 followed by two world wars; t for many generations, particularly those born post -1960 and 1970, who are the current workers of today, this has been the first global disaster that has occurred that has significantly impacted across the globe. Although defined as a health pandemic it may well be regarded as a war, one without end as we await a vaccine and one in which frontline workers, that is healthcare providers, are the soldiers battling an invisible enemy on a daily basis while they may take the enemy home as they return to their family after days spent at work. The aftermath of this war being waged has widespread manifestations that pertain to the mental health of frontline workers, those that lose loved ones, and overall on the future economic stability of countries worldwide. There is thus an urgent need to provide interventions that address the mental health of frontline workers to ensure that as this disease continues to rage, that these workers have some form of mental health support to ensure that they are able to continue in their work of raising and maintaining the line.

Acknowledgements

The researchers thanked study participants who contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statements: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding: The funder of the study had no role in the design of this study and its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.001.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e480. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30068-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chokshi DA, Katz MH. Emerging Lessons From COVID-19 Response in New York City. JAMA. 2020;323:1996–1997. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mounesan L, Eybpoosh S, Haghdoost A, Moradi G, Mostafavi E. Is reporting many cases of COVID-19 in Iran due to strength or weakness of Iran's health system. Iran J Microbiol. 2020;12:73–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Committee on Covid-19 Epidemiology MoH, Medical Education IRI. Daily Situation Report on Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Iran; March 25, 2020. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8:e38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong Y, Peng L. Focusing on health-care providers' experiences in the COVID-19 crisis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e740–e741. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30214-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2014.

- 11.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He K, Stolarski A, Whang E, Kristo G. Addressing General Surgery Residents' Concerns in the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77:735–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houghton C, Meskell P, Delaney H, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers' adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munawar K, Choudhry FR. Exploring Stress Coping Strategies of Frontline Emergency Health Workers dealing Covid-19 in Pakistan: A Qualitative Inquiry. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun N, Wei L, Shi S, et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Wei L, Li H, et al. The Psychological Change Process of Frontline Nurses Caring for Patients with COVID-19 during Its Outbreak. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2020;41:525–530. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2020.1752865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e790–e798. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J Manag Psychol. 2007;22:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24:285–308. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.