Abstract

Background

The utility of heated and humidified high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) for severe COVID-19-related hypoxaemic respiratory failure (HRF), particularly in settings with limited access to intensive care unit (ICU) resources, remains unclear, and predictors of outcome have been poorly studied.

Methods

We included consecutive patients with COVID-19-related HRF treated with HFNO at two tertiary hospitals in Cape Town, South Africa. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who were successfully weaned from HFNO, whilst failure comprised intubation or death on HFNO.

Findings

The median (IQR) arterial oxygen partial pressure to fraction inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2/FiO2) was 68 (54–92) in 293 enroled patients. Of these, 137/293 (47%) of patients [PaO2/FiO2 76 (63–93)] were successfully weaned from HFNO. The median duration of HFNO was 6 (3–9) in those successfully treated versus 2 (1–5) days in those who failed (p<0.001). A higher ratio of oxygen saturation/FiO2 to respiratory rate within 6 h (ROX-6 score) after HFNO commencement was associated with HFNO success (ROX-6; AHR 0.43, 0.31–0.60), as was use of steroids (AHR 0.35, 95%CI 0.19–0.64). A ROX-6 score of ≥3.7 was 80% predictive of successful weaning whilst ROX-6 ≤ 2.2 was 74% predictive of failure. In total, 139 patents (52%) survived to hospital discharge, whilst mortality amongst HFNO failures with outcomes was 129/140 (92%).

Interpretation

In a resource-constrained setting, HFNO for severe COVID-19 HRF is feasible and more almost half of those who receive it can be successfully weaned without the need for mechanical ventilation.

Keywords: COVID-19, Ventilation, High flow nasal oxygen, Pneumonia

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

The utility of high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) for severe Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related hypoxaemic respiratory failure (HRF), particularly in settings with limited access to intensive care unit (ICU) resources, remains unclear. We searched PubMed and Google Scholar for articles published in all languages up to 25 July 2020 using the search terms “HFNO”, “HFNC”, “COVID-19″, “respiratory failure”, “ARDS”, “ICU”, “mechanical ventilation”, and “outcomes”. We identified only 4 studies (2 in non-peer-reviewed preprint format) that evaluated HFNO in COVID-19-related HRF. The four studies together included a total of 312 patients, all were retrospective, and only one study enroled patients from a resource-limited setting (China). Significantly, none were from HIV-endemic or resource-poor (African) settings, and none evaluated the effect of steroids in modulating outcomes, which is now the standard of care.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge this is the largest prospective observational study to evaluate HFNO for severe COVID-19 pneumonia. We showed that HFNO in combination is feasible and can successfully be utilised to provide respiratory support to a significant proportion of patients with COVID-19-related HRF. Moreover, this approach avoided mechanical ventilation even in patients with profound hypoxaemia. A higher ROX index measured at 6 h after HFNO initiation (ROX-6), along with treatment with steroids, independently predicted success. The majority of our patients received HFNO in a ward-based non-critical care environment, demonstrating the feasibility of HFNO outside of the ICU using affordable pulse oximetry-based monitoring.

Implications of all the available evidence

In a resource-constrained setting, HFNO for severe COVID-19 HRF is feasible and more almost half of those who receive it can be successfully weaned without the need for mechanical ventilation.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a potentially fatal infection caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. The highly contagious nature and exponential spread of SARS-CoV-2, coupled with its potential for a rapid progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), has overwhelmed health care systems globally, contributing to the high mortality rates in early reports [1,2].

The initial approach for respiratory support for severe COVID-19 pneumonia centred around invasive mechanical ventilation and the standard lung protective strategy recommended for ARDS [3]. This may have been detrimental to a proportion of patients due to ventilator induced lung injury (VILI) and associated systemic inflammation [4]. Furthermore, other strategies to improve oxygenation may be more appropriate in patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure who do not require ventilatory support [4].

High-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) is delivered by an air/oxygen blender, an active humidifier, a single heated circuit, and a nasal interface. It delivers adequately heated and humidified medical gas at flow-rates of up to 60 L/min, and is considered to have a number of physiological benefits, including the reduction of anatomical dead space and work of breathing, the provision of a constant fraction of inspired oxygen with adequate humidification and a degree of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) [5,6]. Although HFNO was originally utilised in neonatology, its use has extended to adult critical care [6].

The Western Cape Province was the initial epicentre of the outbreak in South Africa, which by early September 2020 was the country with the seventh highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases worldwide [7]. The ratio of ICU to hospital beds in the public health sector in South Africa is only ~4% [8]. In April 2020, in anticipation of the rapid saturation of the existing critical care capacity resources, the two major tertiary centres in Cape Town adopted the use of HFNO, both inside the intensive care unit (ICU) and in non-critical care environments, in an effort to increase the capacity to manage patients with severe respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 [9].

To date, few retrospective studies with limited sample sizes, one of which is from a relatively resource-limited setting (China), have evaluated HFNO in COVID-19-related HRF [10], [11], [12], [13]. However, to what extent HFNO is feasible in a more resource-poor, HIV-endemic, and non-ICU setting, remains unclear. Moreover, the predictors of treatment failure and the modulating effect of steroids thereon remain unclarified. We hypothesised that a significant proportion of patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure could be supported with HFNO as initial support, thereby decreasing the burden on our healthcare system's intensive care platform during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the main aim of this study was to assess the impact of HFNO in avoiding mechanical ventilation in patients with severe respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19. As secondary objectives, we aimed to identify potential physiological parameters or biomarkers predict HFNO failure, and assessed overall survival to hospital discharge.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a prospective multi-centre observational study within the public health system in Cape Town, South Africa. The study was approved by the local ethics committees at each site (UCT HREC 295/2020 and SU HREC S20/05/001_COVID-19), and informed consent was waived in acknowledgement that the intervention was being assessed within the routine service. The study is reported in accordance with the STROBE statement for cohort studies [14] (Supplementary Appendix).

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted at two urban tertiary academic hospitals in Cape Town, South Africa [Groote Schuur Hospital (GSH) and Tygerberg Hospital (TBH)], servicing a population of ~4.5 million with high tuberculosis and HIV prevalence [15]. Patients were enroled from the 19th of April to the 30th of June 2020. During this period, each hospital admitted ~15–20 COVID-19 positive patients per day. At the end of the study period, GSH had admitted 1342 patients with COVID-19, and had increased ICU bed capacity three-fold to 55 beds, admitting ~25–30 ventilated patients to ICU per week during the peak (all HFNO being offered in repurposed medical wards) [16,17]; at TBH, 1016 patients with COVID-19 were admitted during the study period, ICU bed capacity had tripled to 45 beds, and ~25 patients were admitted to ICU (both ventilated and for HFNO) per week during the peak (personal communication, Directorate of Health Impact Assessment, Western Cape Government: Health).

2.3. Participants

Eligible participants were consecutive adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with severe respiratory failure, and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia [detection of SARS-CoV-2 by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on any respiratory sample] who were treated with HFNO during hospitalisation. Severe respiratory failure was defined as a respiratory rate ≥30 breaths per minute with oxygen saturations ≤92% despite oxygen at 15 L/min via reservoir bag, and/or arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ratio<150. The decision to initiate HFNO was at the discretion of the treating clinical team based on a protocol for the stepwise escalation of oxygen therapy, and was contraindicated in patients with exhaustion or confusion. Likewise, the decision of the timing of intubation and mechanical ventilation was not protocolised, but determined by the treating clinical team, and guided by a composite assessment of respiratory effort, patient exhaustion, rising arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) or altered mental state rather than a single measure of oxygenation alone such as saturation or PaO2. Awake prone positioning was encouraged at every clinical encounter and reinforced by nursing staff according to a shared clinical protocol.

Therapeutic interventions like anticoagulation strategy and the use of steroids (both physician directed) were also recorded. No other SARS-CoV-2 directed therapy was provided to any patient, either off-label or as part of a clinical trial, at either hospital during the study period. The start of the study predated the preliminary report of the efficacy of dexamethasone by RECOVERY [18], and prescription of corticosteroids prior to this date was by physician preference. After the 16th of June, all patients on HFNO received either dexamethasone 6 mg intravenously daily, or prednisone 40 mg daily, for 10 days.

3. HFNO

Heated and humidified HFNO was exclusively provided within the ICU at TBH, and within designated medical wards (non-ICU) at GSH where patients were cohorted. Patients wore surgical masks and all personnel were supplied with personal protective equipment, including N95 masks and visors. HFNO was delivered either by a Hamilton C1 ventilator (Hamilton Medical AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland), Airvo࣪ 2 (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Irvine, California, USA) or Inspire࣪ O2FLO (Vincent Medical, Hong Kong, China) machine. Flow was initiated at 50–60 L/min with FiO2 0.8–1.0, titrated to aim for an oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≥92%.

3.1. Procedures

Demographic and clinical variables, and if available, contemporaneous peripheral blood differential counts and inflammatory biomarkers (D-dimer and C-reactive protein) were recorded on commencement of HFNO. HFNO settings (FiO2 and flow rate) along with heart rate, respiratory rate and peripheral oxygen saturations were recorded at 6 h post-initiation of HFNO. Using these variables, we calculated the validated ROX score [19] (ratio of oxygen saturation/FiO2 to respiratory rate) at 6 h (ROX-6) and modified ROX score [20] (ROX score divided by heart rate) at 6 h (mROX-6) score. For patients who were intubated before 6 h, the variables at the time that the decision was made that HFNO was failing were recorded.

3.2. Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with a successful outcome (weaned off HFNO). Failure was defined as composite of the need for intubation or death whilst on HFNO. Of secondary interest were predictors of HFNO failure, and survival to hospital discharge (percentage of patients discharged home alive, or transferred to a rehabilitation facility, excluding patients still admitted and undergoing treatment).

3.3. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and were compared using Pearson's χ2tests or Fisher's exact tests. Continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations, or medians with inter-quartile ranges. Non-parametric data was compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. A CONSORT diagram reported the flow of patients in the study (Fig. 1). The crude cumulative proportion of HFNO success was calculated. Predictors of intubation were primarily analysed using a Cox proportional hazards model, incorporating clinically important variables selected a priori for the model. The index date was the date of initiation of HFNO, with censoring occurring upon intubation, death, or the end of the study (30th June 2020). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed using the software program GraphPad Prism (version 8, GraphPad Software, USA) and Youden's index was calculated to determine the cut-off that maximised sensitivity and specificity for ROX-6 and mROX-6. [21] Descriptive statistics, comparisons between parametric and non-parametric samples, and Cox proportional hazards regression were performed using Stata (V.12.1, Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA) [22].

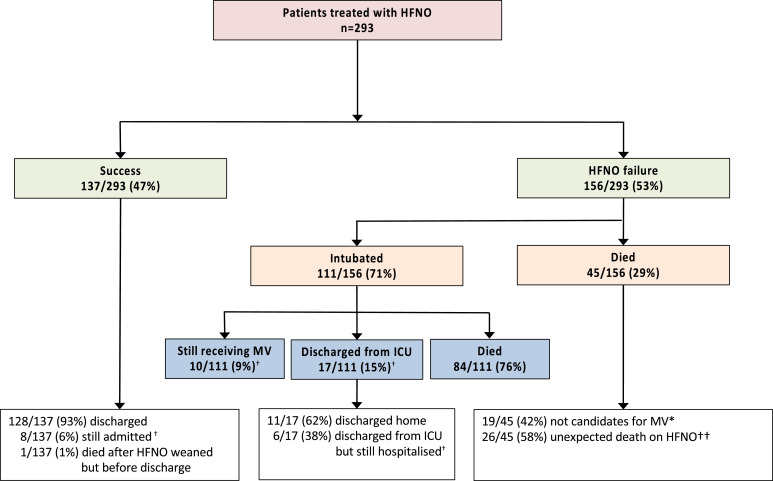

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram showing outcomes of HFNO and survival to discharge.

HFNO: high-flow nasal cannula oxygen; ICU: intensive care unit; MV: mechanical ventilation, DNR: do not resuscitate.

Success = weaned from HFNO; Failure= need for intubation or death.

* Triaged due local facility protocol, DNR order or pre-specified patient preference.

† Survival to hospital discharge = 139/269 (52%): denominator excludes those still in hospital or ventilated in ICU (n = 24).

†† Sudden death = abrupt unexpected death on HFNO (intubation was not being considered at the time).

3.4. Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The first and last authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

4. Results

4.1. Patient population

Two hundred and ninety-three patients were enroled between the 16th of April and 30th of June 2020: 105 (36%) were admitted to the ICU for HFNO, while 188 (64%) received HFNO in the designated COVID-19 ward (non-ICU). The median (IQR) age was 52 (44–58) years; 163/292 (56%) were males. Every patient was on via reservoir face mask at 15 L/min prior to initiation of HFNO; the median (IQR) ratio of PaO2/FiO2 pre-HFNO was 68 (54–92). The median (IQR) duration of symptoms prior to treatment with HFNO was 7 (4–9) days. Comorbidities were highly prevalent: 134/293 (46%) patients were diabetic (with 79/134 (59%) having an HbA1c>8%); 131/293 (45%) were hypertensive, 153/293 (52%) were obese (body mass index≥30), and 45/292 (15%) were HIV positive (Table 1). Therapeutic anticoagulation with enoxaparin at 1 mg/kg 12-hourly was almost universal (281/293, 96%), and 222/293 (76%) received steroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone / hydrocortisone dose-equivalent). Most patients (188/293, 64%) were treated with HFNO outside of the ICU. At any point during the study period, between 25 and 40 patients were being treated with HFNO at each of the participating hospitals.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Total (n = 293) | Failure (n = 156) | Success (n = 137) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 52 (44–58) | 53 (44–58) | 50 (44–57) | 0.187 |

| Sex | ||||

| Males, n (%) | 163 (56) | 84 (54) | 79 (58) | 0.512 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Any diabetes, n (%) | 158 (54) | 82 (53) | 76 (55) | 0.697 |

| Poorly controlled (HbA1c≥8%), n (%) | 79 (27) | 46 (29) | 33 (24) | 0.299 |

| HbA1c, median (IQR) | 9.3 (7.1–11.4) | 9.6 (7.9–11.5) | 8.75 (7–11.3) | 0.259 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| n (%) | 131 (45) | 72 (46) | 59 (43) | 0.562 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| ≤25, n (%) | 31 (11) | 13 (8) | 18 (13) | 0.182 |

| 25–30, n (%) | 109 (37) | 65 (42) | 44 (32) | 0.092 |

| 30–35, n (%) | 94 (32) | 55 (35) | 39 (28) | 0.214 |

| ≥35, n (%) | 59 (20) | 23 (15) | 36 (26) | 0.021 |

| HIV status | ||||

| Negative, n (%) | 211 (72) | 116 (74) | 95 (69) | 0.340 |

| Positive, n (%) | 45 (15) | 22 (14) | 23 (17) | 0.525 |

| Unknown, n (%) | 37 (13) | 18 (12) | 19 (4) | 0.549 |

| CD4 count (if HIV+ve) (cells/m3) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 309 (146–441) | 284 (145–388) | 335 (267–455) | 0.355 |

| ART use (vs. no ART if HIV+ve) | ||||

| n (%) | 36 (80) | 19 (86) | 17 (74) | 0.230 |

| Duration of symptoms prior to HFNO | ||||

| Days, median (IQR) | 7 (4–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (4–8) | 0.107 |

| Modified SOFA score †,† | ||||

| 3–5 | 276 (95) | 146 (94) | 131 (96) | 0.390 |

| >5 | 14 (5) | 9 (6) | 5 (4) | 0.390 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 80 (63–100) | 81 (64–103) | 77 (63–93) | 0.261 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio at HFNO initiation †† | ||||

| mmHg, median (IQR) | 68 (54–92) | 63 (51–83) | 76 (58–102) | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulation with LWMH* | ||||

| None, n (%) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.000 |

| Prophylactic, n (%) | 10 (3) | 3 (2) | 7 (5) | 0.198 |

| Therapeutic, n (%) | 281 (96) | 152 (97) | 129 (94) | 0.237 |

| Steroid treatment† | ||||

| n (%) | 222 (76) | 103 (66) | 119 (88) | <0.001 |

| ICU setting (vs. medical ward) | ||||

| n (%) | 105 (36) | 44 (28) | 61 (45) | 0.004 |

| Lymphocyte count (x109/L)†† | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 1.18 (0.89–1.58) | 1.15 (0.92–1.57) | 1.23 (0.83–1.62) | 0.561 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L)†† | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 184 (11–310) | 235 (142–344) | 173 (105–274) | 0.002 |

| D-dimer (mg/L)†† | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 0.83 (0.41–2.54) | 1.03 (0.49–4.44) | 0.56 (0.36–1.78) | 0.002 |

Note: HFNO = high flow nasal cannula; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral treatment; BMI = body mass index; SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; PaO2/FiO2 = ration of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to inspired oxygen fraction; LMWH = low-molecular weight heparin; CRP = C-reactive protein.

Prophylactic = 0.5 mg/kg enoxaparin daily; therapeutic = 1 mg/kg enoxaparin twice daily (dose adjusted for renal impairment where necessary).

Dexamethasone 6 mg or prednisone 40 mg daily for 10 days.

n = 290,250, 249, 197 and 240 for mSOFA, PaO2/FiO2 ratio at HFNO initiation, lymphocyte count, C-reactive protein and D-dimer results respectively.

4.2. Primary outcome

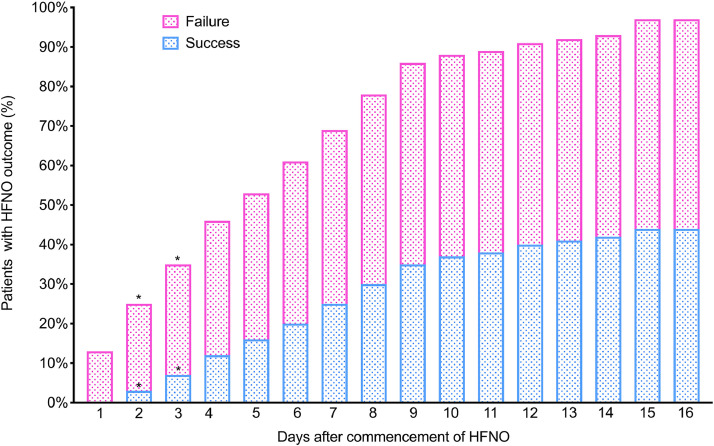

Successful treatment with HFNO was achieved in 137/293 (47%) of patients (Fig. 1); of these, the majority (128/137, 93%) were subsequently discharged from hospital. At the time of writing, 8 patients (6%) had been weaned off HFNO but were still in hospital. The median (IQR) duration of HFNO was 6 (3–9) days in those successfully treated versus 2 (1–5) days in those who failed (p<0.001 (Fig. 2). Of the latter, time to intubation was 2 (0.5–5) days, whilst time to death on HFNO was 4 (2–6) days (p = 0.02).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of patients on HFNO reaching outcome per day of therapy.

The median (IQR) duration of HFNO was 6 (3–9) days in those successfully treated versus 2 (1–5) days in those who failed (p<0.001).

*P<0.05 when compared to proportion of previous day for same outcome (Pearson's χ2 test).

4.3. Predictors of HFNO failure

Differences in demographics, clinical characteristics and inflammatory marker profiles between patients with a successful outcome on HFNO and those with HFNO failure are summarised in Table 1. Patients who had a successful outcome on HFNO had higher oxygen saturations, lower respiratory and heart rates, and lower oxygen requirements (FiO2) within 6 h of commencement of HFNO (Table 2). ROX-6 and mROX-6 were also significantly different amongst patients with HFNO failure vs. success: 2.41 (2.06–3.05) vs. 3.26 (2.72–4.10) for ROX-6 (p<0.001) and 2.33 (1.92–3.12) vs. 3.44 (2.67–4.20) for mROX-6 (p<0.001), respectively (Fig. S1, Supplementary Appendix). 17/293 (6%) patients failed HFNO before 6 h, and had ROX-6 and mROX-6 scores recorded at the time of intubation.

Table 2.

Oxygen requirement and respiratory parameters after 6 h on HFNO.

| Total (n = 293) | Failure (n = 156) | Success (n = 137) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpO2 (%) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 90 (86–94) | 89 (83–92) | 91 (89–94) | <0.001 |

| FiO2 (%) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 90 (85–95) | 90 (90–95) | 90 (80–93) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/mins) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 37 (30–43) | 40 (34–46) | 32 (28–40) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/mins) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 101 (90–108) | 104 (92–110) | 97 (88–105) | <0.001 |

| SpO2/FiO2 ratio | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 100 (93–107 | 98 (89–103) | 104 (98–115) | <0.001 |

| ROX index at 6 h (ROX-6) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.78 (2.25–3.62) | 2.41 (2.06–3.05) | 3.26 (2.72–4.10) | <0.001 |

| Modified ROX index at 6 h (mROX-6) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.90 (2.16–3.74) | 2.33 (1.92–3.12) | 3.44 (2.67–4.20) | <0.001 |

ROX-6 and mROX-6 were very closely correlated (r2=0.870), and both had virtually identical hazard ratios for outcome in univariable analysis (Table 3), so ROX-6 was chosen for the multivariable analysis as it includes one less observation and is easier to calculate. In this model, only poorly-controlled diabetes (HbA1c>8%) (adjusted HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.06–2.28), treatment with steroids (adjusted HR 0.25, 95% CI 0.18–0.37,), ROX-6 score (adjusted HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.33–0.54) were significantly associated with the relative hazard of treatment failure. The association between treatment with steroids and ICU setting was significant (p = 0.004), suggesting that the influence of setting on outcome was largely explained by the increased use of steroids in ICU.

Table 3.

Predictors of HFNO failure.

| Variable | N | Estimated HR* (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR† (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per year increase) | 293 | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.795 | ||

| Male (vs. females) | 293 | 0.95 (0.70–1.29/) | 0.749 | ||

| HIV status (vs. negative) | |||||

| Positive | 45 | 0.75 (0.48–1.19) | 0.224 | ||

| Hypertension | 131 | 0.99 (0.73–1.34) | 0.930 | ||

| Diabetes* | |||||

| Well-controlled (vs. no diabetes) | 55 | 0.97 (0.63–1.50) | 0.883 | 1.27 (0.81–2.00) | 0.301 |

| Poorly controlled (vs. no diabetes) | 79 | 1.31 (0.93–1.88) | 0.143 | 1.56 (1.06–2.28) | 0.023 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2 vs. <30 kg/m2) | 153 | 0.80 (0.58–1.09) | 0.158 | ||

| mSOFA (per 1 point increase) | 290 | 1.18 (1.04–1.36) | 0.054 | ||

| Duration of symptoms (per 1 day increase) | 293 | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.313 | ||

| Treatment with steroids | 221 | 0.31 (0.22–0.44) | 0.001 | 0.25 (0.18–0.37) | <0.001 |

| ICU setting (vs. medical ward) | 105 | 0.68 (0.48–0.97) | 0.032 | ||

| ROX-6 score (per 1 point increase) | 279 | 0.46 (0.37–0.58) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.33–0.53) | <0.001 |

| mROX-6 score (per 1 point increase) | 277 | 0.51 (0.42–0.61) | <0.001 | ||

| Lymphocyte count (per 1 × 109 increase) | 249 | 1.19 (0.92–1.52) | 0.181 | ||

| CRP (vs. <100 mg/L) | 38 | ||||

| 100–199 | 66 | 0.71 (0.38–1.30) | 0.269 | ||

| 200–299 | 50 | 0.88 0.46–1.70) | 0.712 | ||

| 300–399 | 31 | 1.14 (0.59–2.20) | 0.701 | ||

| 400–499 | 15 | 1.54 (0.70–3.38) | 0.280 | ||

| ≥500 | 7 | 2.99 (1.23–7.25) | 0.015 | ||

| D-dimer (vs. <1.5 mg/L) | 150 | ||||

| 1.51–5.0 | 39 | 1.48 (0.93–2.36) | 0.097 | ||

| ≥5 | 42 | 1.99 (1.28–3.12) | 0.002 |

Note: HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; mSOFA = Modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, ICU = intensive care unit; CRP = C-reactive protein.

Well controlled = HbA1c≤8%; poorly-controlled = HbA1C>8%.

ROX-6 used in adjusted model rather than mROX because of similar HR and diagnostic performance (see Fig. S2, Supplementary Appendix) with fewer input variables than mROX-6.

‡Best model fit obtained with inclusion of steroid use, diabetes (poorly-controlled vs. no diabetes), and ROX-6.

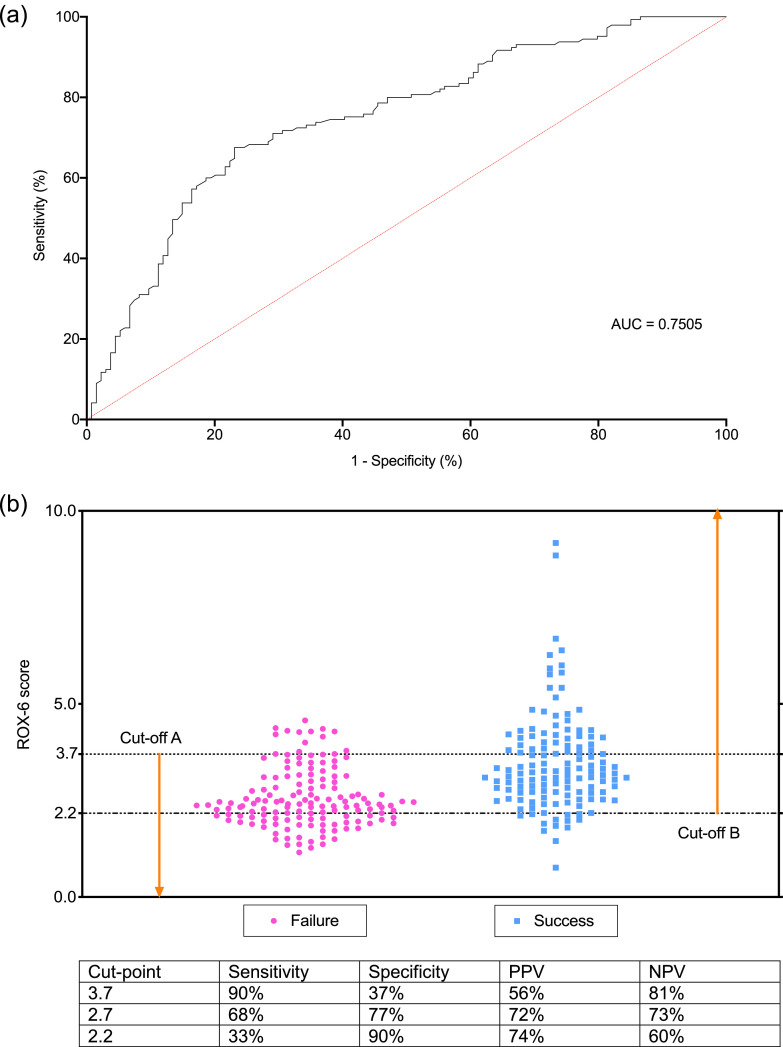

4.4. Diagnostic performance of ROX-6 for HFNO failure

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.75 (Fig. 3A). A ROX-6 below 3.7 (cut-off A, maximising sensitivity) was 90% sensitive (true positives) whilst ROX-6 above 2.2 (cut-off B, maximising specificity) was 90% specific (true negatives) (Fig. 3B). The corresponding positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (PPV) are shown in the table below Fig. 3. The single cut-off that maximised sensitivity and specificity (Youden's index) was 2.7; the PPV and NPV at Youden's index was 72% and 73%, respectively.

Fig. 3.

A. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for ROX-6 for predicting HFNO failure. ROC was performed for ROX-6 (134 patients successfully treated with HFNO and 145 patients who failed HFNO). Area under the curve (AUC) for ROX-6 is 0.75 with p<0.0001. B. Scatter plot of ROX score (ratio of oxygen saturation/FiO2 to respiratory rate) at 6 h (ROX-6) showing cut-offs maximising sensitivity and specificity.

PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value.

A ROX-6 below 3.7 (cut-off A, maximising sensitivity) was 90% sensitive (true positives) whilst ROX-6 above 2.2 (cut-off B, maximising specificity) was 90% specific (true negatives). The single cut-off that maximised sensitivity and specificity (Youden's index) was 2.7; the PPV and NPV at Youden's index was 72% and 73%, respectively.

4.5. Survival to hospital discharge

At the time of analysis, 10/293 (3%) patients were still in the ICU and ventilated, and 14/293 (5%) were still in hospital after either successful HFNO treatment or ICU discharge. Overall survival to hospital discharge for patients treated with HFNO (denominator excluding those still in hospital or ventilated in ICU) was 139/269 (52%), and mortality was 130/269 (48%). In patients successfully treated with HFNO, one patient (1/137, 1%) died after successfully being weaned off HFNO. Of the patients who failed HFNO, 111/156 (71%) were intubated after failing HFNO, and 45/156 (29%) died whilst receiving the therapy. Of the deaths prior to intubation, 26/45 (58%) died unexpectedly before intubation could be considered, and the remaining 19/45 (42%) were assessed as requiring intubation but were declined as non-ICU candidates due local facility protocols, or in a few cases, had pre-specified their preference not to be intubated. Survival to hospital discharge was 128/129 (99%) and 11/140 (7%) in the HFNO success and failure groups respectively (p<0.0001).

5. Discussion

This prospective observational study of HFNO for severe COVID-19 pneumonia is the largest reported to date. Our study showed that HFNO can successfully be utilised to provide respiratory support to patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and HRF, and avoided mechanical ventilation even in patients with profound hypoxaemia. However, HFNO failed in just over half of our cohort, and the mortality in this group of patients who received mechanical ventilation was very high. Although these poorer ventilation outcomes may be the consequence of a patient population suffering from socioeconomic deprivation, multiple comorbidities and high tuberculosis and HIV prevalence, it also raises the possibility that persistence with HFNO in certain patients may delay the inevitable requirement for intubation, which could jeopardise clinical outcomes [23]. This further highlights the need for early differentiation of patients who may benefit from HFNO from those who will require mechanical ventilation, although in our resource-limited setting access to the latter was not unrestricted. We showed that a higher ROX index measured at 6 h after HFNO initiation (ROX-6), along with treatment with steroids, independently predicted success. Moreover, poorly controlled diabetes was associated with HFNO failure. Importantly, treatment with HFNO outside of the ICU, and HIV positive status, did not portend worse outcome.

Most of our patients received HFNO in a non-critical care ward-based environment, demonstrating the feasibility of HFNO outside of the ICU. This potential to increase the capacity to manage severe COVID-19 pneumonia in resource-constrained settings has important implications. In settings where firstly, access to the infrastructure and/or expertise of ICU care is limited, or, secondly, transport of clinically unstable patients to a facility with a designated ICU is potentially hazardous and undesirable, HFNO may be considered as an appropriate mode of respiratory support. While adequate PPE is mandatory for all health care workers attending to patients on HFNO, evidence suggest that the risk of airborne transmission is no greater than the use of face mask oxygen [24]. The degree to which HFNO can be scaled up as a treatment for large numbers of patients with HRF would, however, be highly dependant on local oxygen capacity, the delivery infrastructure within individual hospitals, and the robustness of the supply chain.

Evidence of efficacy of HFNO in reducing the requirement for intubation is consistent with previous studies, albeit in patients with HRF of other causes [25,26]. A meta-analysis of 9 randomised controlled trials of acute HRF in the pre-COVID-19 era found HFNO resulted in lower intubation rates without affecting survival [27]. Preliminary data, mainly case reports and small case series, have also described its potential utility in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia [9,10,[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]], and usually in combination with awake proning [33,34]. The finding that ROX and mROX can be used as a prediction tool is also consistent with studies of early predictors of HFNO outcome in other forms of respiratory failure [19,20]. We found that ROX performed equivalently to mROX, and thus favoured it, as it comprised fewer input variables. In a 2-year multicentre prospective observational cohort study of 191 patients with pneumonia (not related to COVID-19) treated with HFNO, Roco et al. found that 68 (35.6%) required intubation [15]. The prediction accuracy of the ROX index increased over time (area under the ROC curve 2 h, 0.679; 6 h, 0.703; 12 h, 0.759). ROX ≥4.88 measured at 2 (hazard ratio, 0.434; 95% CI, 0.264–0.715; P = 0.001), 6 (hazard ratio, 0.304; 95% CI, 0.182–0.509; P < 0.001), or 12 h (hazard ratio, 0.291; 95% CI, 0.161–0.524; P < 0.001) after HFNO initiation was associated with a lower risk for intubation. A ROX <2.85, <3.47, and <3.85 at 2, 6, and 12 h of HFNO initiation, respectively, were predictors of treatment failure. They found that amongst components of the index, oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry/FiO2 had a greater weight than respiratory rate.

A recently published letter from France (n = 62) [11], two pre-print reports from the same centre in the USA (n = 104 and n = 129) and a study from China (n = 17) [10] evaluated COVID-19 pneumonia treated with HFNO. They found intubation rates of between 31% and 66%, and that ROX (measured within the first 4 h) predicted success [11]. Compared to our study, there were several important differences in the published French study: the median ROX score that predicted survival was 1.5 times higher than ROX-6; time to intubation was much shorter (10 h), and ICU mortality was much lower i.e. 17%. The obvious distinction was the severity of HRF: the mean SPO2 was substantially lower (90 vs 96%) and respiratory rate higher (37 vs 25 per min) in our study population.

The main strengths of this study are the prospective, multi-centre design, the relatively large sample size with completed outcomes collected over a relatively short period of time, and the reporting predictors and outcomes within the context of corticosteroids, which is now the standard of care. The latter is an important point because it will likely impact thresholds for intubation and outcomes including death. In addition, we also clarified the relative importance of the different predictors including the components of the ROX score. It is also the only study from a population with high HIV prevalence, and the first report of the large-scale use of HFNO outside of a standard ICU. The compromise of providing non-invasive respiratory support outside of a conventional ICU setting has been made in other places (such as in Italy [35] – however, these patients were still cared for by intensivists in designated “level 2″ ICU beds).

Some limitations of this study deserve emphasis. We could not adequately control for differences in physician experience and judgement around the timing of intubation. However, well-outlined protocolised provincial guidelines for intubation and mechanical ventilation, including score-based risk stratification (based on SOFA score, pre-morbid status, comorbidities and age) were followed [36]. Studies utilising composite physiological scores to determine predictors for the need for intubation inherently suffer from confirmation bias [19,20,37,38], as even if the ROX index is not formally calculated, the individual components (SpO2, FiO2 and respiratory rate) are incorporated in a Bayesian-type reasoning by the clinician in making the intubation decision. Nevertheless, an objective measure that crystallises the current respiratory parameters, and can potentially reassure the clinician about the safety of continuing with HFNO, is still useful. Biomarker data was incomplete, thus reducing the power of the multivariable prediction model. However, this was a pragmatic ‘real-world’ study where blood sampling was clinically driven rather than protocolised outside the ICU. Our study was also not randomised (with a “usual care” as an alternative) but this would have been impractical given the scale of the pandemic and the limited intensive care resources. Lastly, intermittent proning was routinely performed, making it impossible to determine the impact of HFNO without prone positioning.

In conclusion, in a resource-constrained setting where access to ICU care and mechanical ventilation is limited, HFNO for severe COVID-19 HRF is feasible and deliverable even in a ward-based non-critical care environment, and more almost half of those who receive it can be successfully weaned without the need for mechanical ventilation. Conversely, mortality in patients who fail HFNO is high.

Declaration of Competing Interest

BA has received speakers fees from Novartis, and CK has served on an advisory board from AstraZeneca, both outside the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the South African MRC (RFA-EMU-02–2017).

Contributors

GC, UL, GA, MGM, KD and CK were involved in the conception and design. GC, UL, GA, DM and CK were involved in study implementation and data collection. GC, SM, and FL did the analysis. GC, UL, MGM, JP, KD and CK interpreted the data and provided important intellectual input. GC, UL, KD and CK wrote the first draft. All authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Data sharing

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the medical, nursing, management and support staff at Groote Schuur and Tygerberg Hospitals for their tireless efforts in caring for our patients, and towards combatting COVID-19 in Cape Town.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100570.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alhazzani W, Møller HM, Arabi Y, Loeb M. Surviving Sepsis Campaign:guidelines on the management of critically Ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gattinoni L., Chiumello D., Caironi P. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1099–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mauri T., Wang Y.M., Dalla Corte F., Corcione N., Spinelli E., Pesenti A. Nasal high flow: physiology, efficacy and safety in the acute care setting, a narrative review. Open Access Emerg Med. 2019;11:109–120. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S180197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishimura M. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in adults. J Intensive Care. 2015;3(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johns Hopkins University. Corona Virus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html(accessed September 7 2020,).

- 8.Bhagwanjee S., Scribante J. National audit of critical care resources in South Africa - unit and bed distribution. S Afr Med J. 2007;97(12 Pt 3):1311–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalla U, Allwood BW, Louw EH, et al. The utility of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in the management of respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia; 2020. [PubMed]

- 10.Wang K., Zhao W., Li J., Shu W., Duan J. The experience of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in two hospitals of Chongqing, China. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00653-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zucman N., Mullaert J., Roux D., Roca O., Ricard J.D. Contributors. Prediction of outcome of nasal high flow use during COVID-19-related acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guy T., Créac'hcadec A., Ricordel C. High-flow nasal oxygen: a safe, efficient treatment for COVID-19 patients not in an ICU. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01154-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochwerg B.A.-.O., Solo K.A.-.O., Darzi A.A.-.O., Chen G.A.-.O., Khamis A.A.-.O. Update Alert: ventilation techniques and risk for transmission of coronavirus disease. Including COVID-19. 2020 doi: 10.7326/L20-0944. LID -[doi] LID - L20-0944 FAU - Rochwerg, Bram(1539-3704 (Electronic)) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Zyl Smit R.N., Pai M., Yew W.W. Global lung health: the colliding epidemics of tuberculosis, tobacco smoking, HIV and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(1):27–33. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00072909. 35/1/27 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendelson M, Boloko L, Boutall A, et al. Clinical management of COVID-19: experiences of the COVID-19 epidemic from Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa; 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mendelson M, Booyens L, Boutall A, et al. The mechanics of setting up a COVID-19 response: experiences of the COVID-19 epidemic from Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa; 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.RECOVERY. Low-cost dexamethasone reduces death by up to one third in hospitalised patients with severe respiratory complications of COVID-19. https://www.recoverytrial.net/news/low-cost-dexamethasone-reduces-death-by-up-to-one-third-in-hospitalised-patients-with-severe-respiratory-complications-of-covid-19(accessed 16 June 2020).

- 19.Roca O., Caralt B., Messika J. An index combining respiratory rate and oxygenation to predict outcome of nasal high-flow therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(11):1368–1376. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0589OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goh K.J., Chai H.Z., Ong T.H., Sewa D.W., Phua G.C., Tan Q.L. Early prediction of high flow nasal cannula therapy outcomes using a modified ROX index incorporating heart rate. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:41. doi: 10.1186/s40560-020-00458-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruopp M.D., Perkins N.J., Whitcomb B.W., Schisterman E.F. Youden Index and optimal cut-point estimated from observations affected by a lower limit of detection. Biom J. 2008;50(3):419–430. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.StataCorp . StataCorp LP.; TX: 2011. Stata statistical software: release 12.: college station. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang B.J., Koh Y., Lim C.M. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(4):623–632. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J., Fink J.B., Ehrmann S. High-flow nasal cannula for COVID-19 patients: low risk of bio-aerosol dispersion. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00892-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J., Jing G., Scott J.B. Year in review 2019: high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy for adult subjects. Respir Care. 2020;65(4):545–557. doi: 10.4187/respcare.07663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyons C., Callaghan M. The use of high-flow nasal oxygen in COVID-19. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(7):843–847. doi: 10.1111/anae.15073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rochwerg B., Granton D., Wang D.X., Einav S., Burns K.E.A. High-flow nasal cannula compared with conventional oxygen therapy for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: author's reply. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(8):1171. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05658-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.W-j Guan, Z-y Ni, Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geng S., Mei Q., Zhu C. High flow nasal cannula is a good treatment option for COVID-19. Heart Lung. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu X., Xu S. Therapeutic effect of high-flow nasal cannula on severe COVID-19 patients in a makeshift intensive-care unit: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(21):e20393. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Q., Wang T., Qin X., Jie Y., Zha L., Lu W. Early awake prone position combined with high-flow nasal oxygen therapy in severe COVID-19: a case series. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):250. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03001-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respirat Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karamouzos V., Fligou F., Gogos C. High flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in adults with COVID-19 respiratory failure. A case report. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020;90(2):256. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2020.1323. 10.1097/md.0000000000020393 10.4081 /monaldi.2020.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slessarev M., Cheng J., Ondrejicka M., Arntfield R. Patient self-proning with high-flow nasal cannula improves oxygenation in COVID-19 pneumonia. Can J Anaesth. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01661-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Western Cape Department of Health. Western Cape Critical Care Triage Tool Version 1.2. 2020, May 18. https://www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/departments/health/COVID-19/western_cape_critical_care_triage_tool_version_1.2_14th_may.pdf (accessed 2020, June 1.

- 37.Mauri T., Carlesso E., Spinelli E. Increasing support by nasal high flow acutely modifies the ROX index in hypoxemic patients: a physiologic study. J Crit Care. 2019;53:183–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spinelli E., Roca O., Mauri T. Dynamic assessment of the ROX index during nasal high flow for early identification of non-responders. J Crit Care. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.