Abstract

A copper (II) complex [Cu(4-MeO-salox)2](1) based on saloxime ligand was synthesized and characterized using single crystal X-ray diffraction studies. The geometry was further emphasized by DFT optimization. The complex was found to be pseudo-macrocyclic mononuclear having square planer geometry. The complex 1 shows two types of supramolecular hydrogen bonding interactions and forms the multi-dimensional framework with the help of CH∙∙∙O, OH∙∙∙O and π∙∙∙π(chelate) interactions. The complex 1 performs as efficient catalyst in catecholase activiy having good turnover number (TON), kcat = 22.97 h−1 where TON is the number of catechol molecules converted into quinone by catalyst molecule i.e 1 in a unit time.

Keywords: Inorganic chemistry, Theoretical chemistry, Saloxime based Cu(II) complex, Synthesis and crystal structure determination, Supramolecular interaction, UV-Vis spectral studies, TD-DFT/B3LYP calculations, Catecholase activity study

Inorganic chemistry; Theoretical chemistry, Saloxime based Cu(II) complex; Synthesis and crystal structure determination; Supramolecular interaction; UV-Vis spectral studies; TD-DFT/B3LYP calculations; Catecholase activity study.

1. Introduction

Phenolic oximes are widely used in industrial copper extraction process from waste streams, and as corrosion protectors in protective coatings. They exhibit selective preference for copper (II) over the other metals, particularly over iron present in pregnant leach solutions. The large selectivity for copper (II) is due to the fact that it perfectly fits in the cavity created by two hydrogen bonded ligands, producing a stable pseudo-macrocyclic monomer (Scheme 1). Mononuclear complexes of Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) with these phenolic oximes are also known to be formed. One more important aspect of phenolic oximes is the capability to form polynuclear complexes since both the oximate and phenolate groups be able to bridge the metals [1]. Scheme 2 represents the different coordination modes [2] by which oxime and oximato groups can bind a metal ion. Polynuclear complexes of Cr, Mn, Fe, and Co with phenolic oximes are also reported. Iron complexes of these oximes have extensive applications as corrosion protector. The importance of such type of ligands binding to identical or different metals is due to different modes of magnetic exchange interactions among the metal ions small moleculer magnetic behaviour, and the stabilization of mixed-valent species [1, 2].

Scheme 1.

The pseudo-macrocyclic cavity created via Hydrogen-bonding between phenolic oximes in 2:1 metal complex. M (Cu and Co) is in the +2 oxidation state.

Scheme 2.

The crystallographically established coordination modes of oximes and oximato groups.

The nucleophilic addition of aldoximes or ketoximes towards electrophilically activated ligands having double and triple bonds are very limitedly reported [3, 4]. It was further explored that this interesting addition of oxime ligands to the organonitriles in PtIV and ReIV coordination complexes form stable monodentate iminoacylated moiety that simultaneously coordinates to the metal center [5, 6, 7, 8]. Formation of pseudo-macrocyclic monomer complex with Cu(II) is also one of the most attention grabbing features of phenolate oximes [9].

Moreover, enzymes containing Cu(II) [10] like tyrosinase, hemocyanin, and catechol oxidase control numerous biochemical reactions rate in alive systems. The active sites of thesetype-III copper proteins contain magnetically coupled binuclear Cu(II) centers. These metallo-enzymes take vital part in the selective oxidation of organic compounds promoting the activation of dioxygen [11]. Tyrosinase regulates the oxidization of phenols into catechols (catecholase activity), followed by catechols into o-quinones (catecholase activity). On the other hand, the enzyme catechol oxidase oxidizes catechols to o-quinones, highly reactive compounds that undergo auto-polymerization to generate a brown pigment melanin, that protects the tissues of higher plants from damage against insects and pathogens [12].

The oxidase (oxygenase) activity of model coordination complexes for metalloenzymes are of picky interest for the progression of bioactive catalysts for oxidation reactions [13]. In thisperspective, the type-3 dicopper enzyme catechol oxidase employs aerobic dioxygen to attain the specific oxidation of catechols to orthoquinones [14]. A range of dinuclear copper-contain functional models of this metalloenzyme have been progressed during the last decades [15, 16, 17].

In the present endeavor, we are projected to reveal synthesis and crystal stucure of the stable complexation of oxime with Cu(II) in MeOH in presence of triethylamine (TEA) as a base and supramolecular interactions like CH∙∙∙O, OH∙∙∙O and π∙∙∙π(chelate) interactions are capable of forming the multi-dimensional framework. For 1, the supramolecular assemblies i.e. π···π stacking interaction forms a 1D array which is further expanded through two different types of C–H···O and OH···O hydrogen bondings to ensure a 2D framework. This Cu(II) complex also shows efficient catalytic efficasy towards catecholase activiy.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and methods

The starting materials 4-methoxy-salicylaldehyde was procured from Lancaster. Hydroxylamine hydrochloride, sodium azide, anhydrous Na2SO4, and CuCl2.2H2O were purchased from Merck, India. Tetrabutyl-ammonium hydroxide was of SRL, India. Solvents like methanol, diethylether, and acetonitrile were of reagent grade and dried before use.

2.2. Physical measurements

A Nickolet Magna IR 750 FTIR spectrometer (series-II) was used to record the Infrared spectra (400–4000 cm−1) in liquid state. Bruker NMR spectrometer (300 MHz) was utilised for recording 1H-NMR spectra. The absorption spectra were carried out on a Jasco V660 spectrophotometer (Jasco, Hachioji, Japan) using quartz cuvettes of 10 mm path length.

2.3. Synthesis and characterization

2.3.1. Synthesis of the 4-OMe-H2salox (H2L)

The solution of 4-methoxy-salicylaldehyde (3.04 g, 20 mmol) (Scheme 3) in ethanol (60 mL) was stirring with NH2OH.HCl (2.76 g, 40 mmol) in 20 mL of water. After that 20 mL of aqueous solution of Na2CO3 (4.00 g, 40 mmol) was then added in the resulting mixture and was refluxed at 80 °C. The reaction progression was tailored by TLC (solvent: 1/1 hexanes/EtOAc). The solid product was precipitated out from reaction mixture which was then filtered with celite bed and was collected by washing with cold water. The needle like crystalline material (4-MeO-H2salox) was obtained after recrystallization from methanol. Yield: 2.17g (65 %). M.P.:133–134.5 °C. 1H NMR (d, ppm; 300 MHz, DMSO-d6): 3.73 (3H, m, aromatic protons),6.86–7.38 (3H, m, aromatic protons), 8.12 (1H, s, methyne), 9.68 (H, bs for Phenolic OH proton), 10.21 (1H, s, N–OH proton).

Scheme 3.

The schematic routes for the preparation of complex 1 with oxime ligand.

2.3.2. Synthesis of complex [Cu(4-MeO-salox)2](1)

The reaction between 4-MeO-H2salox and CuCl2 in presence of TEA in MeOH gives complex [Cu(4-MeO-salox)2](1) [18]. The pale yellow solution of 4-MeO-H2salox (0.167g, 1.0 mmol) in 30 mL of DMSO: DCM (2:1, v/v) was stirred and the solid [Cu(bpy)Cl2] (0.290 g, 1.0 mmol) (Scheme 3) was stirred after adding to it. The resulting solution was then stirred continued for 2h with the addition of TEA (triethylamine) (0.202 g, 2.0 mmol) and the colour of the resulting solution became green. After completion of the reaction, the filtrate without any precipitation was kept aside uninterrupted for slow evaporation. The green block-shaped crystals were formed after 5 days, and collected them by filtration. Yield 0.25g (65%) based on copper content. IR analysis: 3125 b cm−1 for ν(-OH), 1625 cm−1 for ν(N=C). Elemental analysis for molecular formula C16H16CuN2O6(M.W. 395.86) Calc.C 48.55%,H 4.07%, N 7.08% Found C 48.59 %,H 4.05%, N 7.10%.

2.3.3. Crystallographic analysis

A Bruker SMART APEX-II CCD diffractometer equipped with graphite monochromated Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Ǻ) was used to collected the single crystal X-ray data of the complexwas on using. Data collection, reduction, structure solution, and refinement were carried out by employing Bruker APEX-II suite (v2.0-2) program [19]. All resultant reflections correspond to 2θmax were collected and corrected for Lorentz and polarization factors with Bruker SAINT plus. After that corrections for absorption, inter frame scaling, and other systematic errors were corrected with SADABS [20]. The structures were resolved using direct methods and refinement was computed by means of full matrix least-square technique with SHELX-97 software package [21] based on F2. by HFIX command were performed to fix all the hydrogen atoms geometrically and positioned at the ideal positions. Calculations were computed with the WinGX system Ver-1.80 [22]. The other non-hydrogen atoms were refined with the thermal anisotropic parameters. Mercury 3.1 programme was employed to generate the drawing of resultant molecules. The crystallographic data are listed and summarised Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement of 1.

| Empirical formula | C16 H16 Cu N2 O6 (ccdc no. 900538) |

|---|---|

| Formula weight | 395.86 |

| Temperature | 296 K |

| Wave length | 0.71073Å |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/n (No. 14) |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 6.4125 (5)Å, b = 18.2936 (16) Å, c = 7.1201 (6) Å β = 103.669 (5)° |

| Volume | 811.59 (12) Å3 |

| Z | 2 |

| Density (calculated) g.cm−3 | 1.620 |

| Absorption coefficient(μ) | 1.382 |

| F (000) | 406 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.02 × 0.08 × 0.12 |

| Index ranges | -7: 7; -22: 22; -8: 8 |

| θ range for data collection | 2.2 to 25.7° |

| Total, Unique Data, R (int) | 11748, 1538, 0.031 |

| Observed data [I > 2.0 σ(I)] | 1328 |

| Completeness to θ = 27.6° | 100 % |

| Absorption correction | Empirical |

| Nref, Npar. | 1538, 117 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 0.99 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0275, wR2 = 0.1036 |

2.3.4. Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) was employed to optimize the ground state electronic structure of 1 in gas phase [23]. The method was coupled with the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) [24]. Becke's hybrid function [25] along the Lee-Yang-Parr (LYP) correlation function [26] was utilised all over the theoretical study. The absorbance spectral properties in DMSO medium was calculated by Time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) [27] linked with the CPCM model was used for calculation. Calculation for the transitions with lowest 40 doublet – doublet (as Cu(II) is d9 system, S = 1/2) was carried out for obtaining the theoretic UV-Vis spectral transitions and results of the TD calculations were qualitatively very similar with experimental.

For the DFT calculations 6–31 + g basis set was used for C, H, N, O, and Cu atoms and performed with the Gaussian 09W software package [28]. The molecular orbital contributions from groups or atoms were computed by the Gauss Sum 2.1 program [29].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural descriptions

The reaction between 4-MeO-saloH2 and CuCl2 in presence of TEA in MeOH gives complex [Cu(4-MeO-saloH)2(1)], in quantitative yield but if this reaction takes place in MeCN then one tridentate iminoacylated ligand may form by the nucleophilic attack of oxime-O atom (-C=NOH) on –C≡N centre of acetonitrile to form monodentate iminoacylated complex [5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

The structural analyses from single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies shows that complex 1 is a CuII mononuclear species that comprises of one CuII ions and two tridentate NO2 donor 4-MeO-saloH2 ligands. It is crystallized in a monoclinic system with space group P21/n. The structure consists of a discrete [CuII(4-MeO-saloH)2] as a neutral species in which the ligand is mono-deprotonated, presented in Figure 1a. The CuII atom is coordinated with two tridentate 4-MeO-saloH2 ligands specifically through N1 and O2 and their symmetry related counter atoms to form tetracoordinated complex which adopted square planer geometry. The bond lengths arround the Cu atom are Cu1–Ni (N1 and N1a)~1.932Å and Cu1-Oi (O2 and O2a)~1.898Å (i = inversion center). The selective bond angles and bond lengths are enlisted in Table 2. Here, free protonated oxime –OH groups are also in bonding distances though it is not capable of forming octahedral geometry as in planer way. In the asymmetric unit, the monomer is intramolecularly H-bonded (1.955Å) by the phenolate oxygen and oxime proton (-C=NOH) (Figure 1) to structure a stable pseudo-macrocyclic framework. The nearest Cu•••Cu internuclear distance is 6.414Å. The mean deviation between Cu1 and well defined planes around Cu1 (Cu1 N1 N1i O1 O1i) is 0.000Å and it shows that the complex is perfect square planar.

Figure 1.

(a) ORTEP view (50% ellepsoid probability) of the pseudo-macrocyclic mononuclear complex 1; (b) H-bonding interactions: the supramolecular dimer, molecular synthon R22(4); (c) One dimensional (1D) supramolecular tape, molecular synthon R22(8) of 1; (d) π∙∙∙π(chelate) interactions, CH∙∙∙O interaction and OH∙∙∙O interaction composed in 1. H-atoms (except some) are omitted for clarity.

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) of 2.

|

Bond Distances (Å) | |||

| Cu1 –O2 | 1.898 (15) | Cu1 –O2a | 1.898 (15) |

| Cu1 –O3 | 2.859 (2) | Cu1 –O3a | 2.859 (2) |

| Cu1 –N1 |

1.932 (2) |

Cu1 –N1a |

1.932 (2) |

|

Bond Angles (°) | |||

| O2 –Cu1–O3 | 117.59 (6) | O3–Cu1–N1a | 154.28 (8) |

| O2 –Cu1–N1 | 91.92 (7) | O2a -Cu1-N1 | 88.08 (7) |

| O2 –Cu–O2a | 180.00 | O3a -Cu1-N1 | 154.28 (8) |

| O2–Cu1–O3a | 62.41 (6) | N1–Cu1–N1a | 180.00 |

| O2–Cu1–N1a | 88.08 (7) | O2a -Cu1-O3a | 117.59 (6) |

| O3 –Cu1–N1 | 25.72 (8) | O2a -Cu1-N1a | 91.92 (7) |

| O2a -Cu1-O3 | 62.41 (6) | O3a -Cu1-N1a | 25.72 (8) |

| O3–Cu1 –O3a | 180.00 | ||

Symmetry operator a = 2-x,-y,1-z.

From the single crystal X-ray diffraction studies, it was shown that there were various types of supramolecular interactions present in the crystal exhibit a crystallographic arrangement. By inspection of molecular assemblies through supra-molecular interactions on 1 showed that 1 forms two types (A and B) of hydrogen bonding interaction. The Type A: the inter molecular H-bonding (Table 3) is between oxime-OH (O3) and oxime-OH(O3a) of neighbor's and vice-versa; O3–H3···O3a = 2.619Å (Figure 1b) with molecular synthon R22(4) in graph set motif and likewise, Type B: the inter molecular H-bonding is CH∙∙∙O interactions (Figure 1c) between azomethine proton (C7–H7) and oxime–OH (O3); C7–H7···O3 = 2.480Å with supramolecular synthon R22(8) in graph set motif and form 1D network crystallographic b axis. The conception of the supramolecular synthons is a very crucial step to understand the association of molecular crystals. It is nothing but a retrosynthetic route where fragmentation of the crystal structures can be done into supramolecular synthons [30].

Table 3.

Hydrogen bonds for 1 [Å and °].

| D-H...A | d (D-H) | d (H...A) | d (D...A) | <(DHA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7 – H7...O3 | 0.930 | 2.480 | 3.308 (3) | 148.00 |

| O3 –H3...O3a | 0.821 | 2.619 | 3.049 (2) | 65.73 |

Simultaneously, the CH···O, OH···O and π∙∙∙π(chelate) interactions are capable of forming the supramolecular tetramer in crystallographic ac plane in 1 (Figure 1d). In this tetramer, the non-covalent π···π(chelate) (3.740Å) (Figure 1d) between the centroid of benzene ring and the centroid of chelation with copper atom and NO donor of oxime. In the transition metal complexes, the non covalent π···π ineractions take part in an important role in the construction of a supramolecular architecture. This π···π interaction requires an appropriate geometrical conformation by which the π orbitals lobes of ligands to position either face to face or to somewhat parallel maintaining distance up to 3.8 Å [31]. In this particular case, the said distance is 3.740 Å.

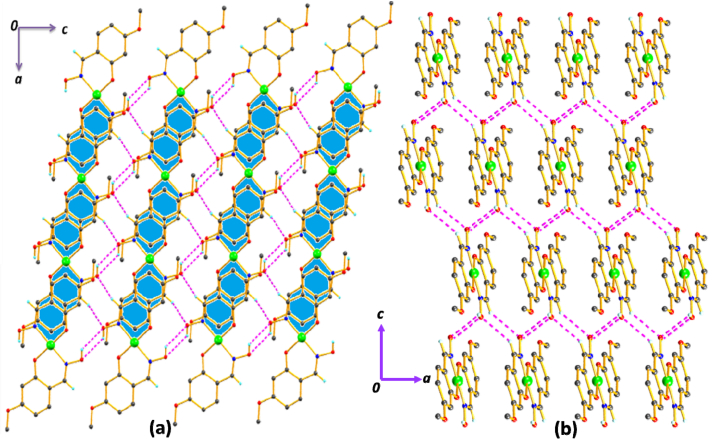

The combinatorial effect of hydrogen bonding: Type-A and Type-B are extended in an one dimensional (1D) network (Figure 2) along crystallographic c axis. This 1D supramolecular assembly is further expanded with the help of CH∙∙∙O, OH∙∙∙O and π∙∙∙π(chelate) interactions to 2D framework in crystallographic ac plane and with inversion of plane (Figure 3 a, b). Hydrogen bonding parameters are tabulated in Table 3.

Figure 2.

The H-bonding interactions with the combination of Type-A and Type-B form 1D supramolecular network along crystallographic c axis for 1. Some H-atoms are omitted for clarity.

Figure 3.

(a) and (b) 2D framework composed of π∙∙∙π(chelate) interactions, CH∙∙∙O and OH∙∙∙O interactions in crystallographic ac plane for 1. Some H-atoms are omitted for clarity.

Symmetry operator a = 2-x,-y,1-z.

3.2. Electronic spectra

UV-vis spectra can be a good detector of geometry for complexes of copper Schiff base [25, 26]. Electronic spectra of complex 1 shown in Figure 4 were recorded in MeOH (4 × 10−5 (M)) solution. The one band at 323 nm (ε = 2.4 × 104 M−1 cm−1) in the electronic spectrum is due to intra-ligand transition. The another lower intensity band at 397 nm (ε = 1.4 ×104 M−1 cm−1) is the indication of a tetra coordinated square planer Cu(II) center [32] and generally recognized as ligand to metal charge transfer transition (LMCT).

Figure 4.

Electronic spectra of 1 in methanol.

3.3. Geometry optimization and electronic structure

The optimized geometry of complex 1 is similar with molecular structure obtained from SCXRD in Figure 5. The difference of energy between HOMO and LUMO is 4.18 eV (Figure 5a). The diagram of frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) with their corresponding positive and negative regions for the optimization of 1 has been depicted in Figure 5. The positive and negative lobes are shown by green and orange colour, respectively.

Figure 5.

(a) Frontier molecular orbital (left) and optimized geometry (right) of 1, (b) frontier molecular orbitals (with iso-surface value 0.02) involved in the UV-Vis absorption of the 1 in MeOH solution.

The experimental absorption bands have been explained by of TD-DFT calculations [33]. In the ground state optimized stucture of 1, the electron cloud remains mostly on HOMO-1, LUMO and LUMO+2 orbitals presents at the benzene ring with –OMe groups while the electron density on HOMO, HOMO–2, LUMO+1 and LUMO+3 orbital resides at π and π∗ orbitals involvement of benzene ring of ligand alongside with metal's d orbital contribution.

The UV-Vis spectra of the 1 were performed at room temperature in MeOH. The complex (1) showed two well determined absorption bands are situated at 320 and 399 nm, having ILCT and LMCT transitions feature respectively, which are in well corroborate with experimental results of 323 and 397 nm. These two absorption peaks can be predicted as the S0→S5 and S0→S3 electronic transitions (Figure 5b) with oscillator strengths f = 0.1426 and f = 0.0719 (Table 4) respectively.

Table 4.

The comparable calculated absorbance λmax with experimental values for the complex 1.

| Theoretical (nm) | Experimental (nm) | Composition | CI | Electronic Transition | Energy (eV) | f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 320 | 323 | HOMO→LUMO HOMO-1→LUMO |

0.0259 0.3149 |

S0→S5 | 4.1652 | 0.1426 |

| 399 | 397 | HOMO-1→LUMO+1 HOMO→LUMO+2 |

0.2017 0.8161 |

S0→S3 | 3.8063 | 0.0719 |

3.4. Catechol oxidase mimicing activity and kinetic studies

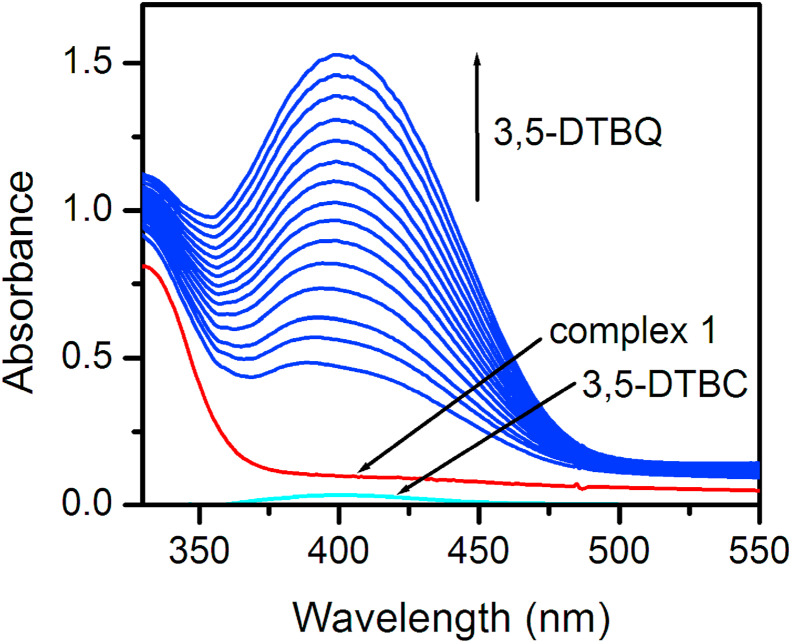

In order to investigate the biomimicking catecholase activity of 1, 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechol (3,5-DTBC) was taken as substrate. The low redox potential of 3,5-DTBC helps for easy oxidation and the bulky tert-butyl substituents protects from over-oxidation as well as ring-opening [34]. The oxidized product 3,5-di-tert-butylquinone (3,5-DTBQ) (Scheme 4) is very stable and exhibits an absorption maximum at 401 nm in methanol [35]. The capability of the Cu(II) complex to mediate the oxidation of 3,5-DTBC was investigated UV−Vis spectroscopy. A 10−4 M solutions of 1 (1 × 10−4 mol ⋅ dm−3) was treated with 100 equivalents of 10−3 M solutions of 3,5-DTBC (1 × 10−3 mol ⋅ dm−3), under aerobic conditions in methanol. On incremental addition of the substrate 3,5-DTBC, the absorption band around 400 nm showed 70% hyperchromicity, which indicates of the production of the corresponding quinone 3,5-DTBQ During the experiment, the quinone absorbance band was found to be increased with time (Figure 6).

Scheme 4.

Reaction pathway of the oxidation catalyzed by 1.

Figure 6.

Time-resolved spectra of quinone at 400 nm after incremental addition of 3,5-DTBC (1 × 10−3 M) to the solution of 1 (1 × 10−4 M) in methanol.

The kinetics studies of 3,5-DTBC oxidation to form 3,5-DTBQ catalyzed by 1 was measured by the initial rate method, monitoring the increase in the absorbance band at 400 nm at 25 °C. The rate constant was calculated from the plot of log [Aα/(Aα-At)] versus time. The dependence of substrate concentration on the rate of oxidation was investigated keeping the Cu(II) complex concentration constant as 10−4 M and increasing the substrate from 1 × 10−3 to 1 × 10−2 mol. dm−3. At low concentrations of substrate, the first order dependence was observed. Whereas, saturation kinetics was observed at higher concentrations of substrate (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Plot of the initial rates versus substrate concentration for the oxidation of 3,5-DTBC catalyzed by 1. Inset: Lineweaver–Burk plot.

Michaelis–Menten theory for enzymatic kinetics was utilized and the Lineweaver–Burk (double reciprocal) plot [11] was constructed to analyze the results obtained from the plot of rate constants vs. substrate concentration. From the Lineweaver– Burk graph: 1/V vs. 1/[S] (Figure 7), using equation 1/V = {KM/Vmax}×{1/[S]} + 1/Vmax, the Michaelis−Menten constant (KM), maximum initial rate (Vmax), and rate constant (kcat) are extracted for 1 The turnover number (kcat) was calculated by dividing the Vmax values by the concentration of the complex. The turnover number (kcat,TON) is the number of catechol molecules converted into quinone by catalyst molecule (here 1) in a unit time. The kinetic parameters are presented in Table 5. The obtain data from the Lineweaver–Burk plot are reasonable for catalytic activity measurements though the actual mechanism of this reaction may be quite complicated. The calculated kcat (22.97 h−1) value for complex 1 is almost similar to the reported value by Krebs et al. [36] (4 h−1 to 214 h−1).

Table 5.

Kinetic parameters for the oxidation of 3,5-DTBC to 3,5-DTBQ catalysed by 1 in methanol.

| Vmax (M ⋅ min−1) | KM (M) | kcat (h−1) | kcat/KM (h−1 ⋅ M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.297 × 10−3 | 1.81 × 10−2 | 22.97 | 12.69 ×102 |

Therefore in literatures, a lot of copper (II) complexes showed excellent catecholase activities [37, 38, 39] but Cu(II) complexes [40] obtained through the use of the dioxime ligand and as co-ligand 1,10-phenantroline exhibited the catecholase activity in very mild rate. Here in this report, the Cu(II) complex of oxime ligand shows excellent efficasy of catecholase acitivity so far.

4. Conclusions

The synthesis, structural as well as catecholase activity of a mononuclear square planer Cu(II) complex was demonstrated. The copper (II) complex exhibits numerous interesting characters in the single crystal X-ray structure analysis process. The stable complexation of oxime with Cu(II), in MeOH form pseudo-macrocyclic mononuclear complex and also capable of forming the multi-dimensional framework by the help of CH∙∙∙O, OH∙∙∙O and π∙∙∙π(chelate) interactions. The Cu(II) complex performed as efficient catalyst and display good efficasy towards catecholase activiy having TON, kcat = 22.97 h−1.

Declarations

Author contribution

Statement Malay Dolai: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Urmila Saha: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

MD gratefully acknowledges to Prabhat Kumar College, Contai, West Bengal, India for giving instrumental supports for this research. We gratefully acknowledge Science & Engineering Research Board (SERB), Govt. of India for the award of National Post-Doctoral Fellowships to US (ref. No.PDF/2016/000080) and MD (ref No.PDF/2016/000334).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

CCDC 900538 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for 1. These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html, or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: (+44) 1223-336-033; or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Jeon I.R., Clérac R. Controlled association of single-molecule magnets (SMMs) into coordination networks: towards a new generation of magnetic materials. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:9569–9586. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30906h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kim J., Lim J.M., Do Y. A novel one-dimensional chain complex composed of oxo-centered trinuclear manganese clusters. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003:2563–2566. [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu H.-B., Wang B.-W., Pan F., Wang Z.-M., Gao S. Stringing oxo-centered trinuclear [MnIII3O] units into single-chain magnets with formate or azide linkers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:7388–7392. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kukushkin V.Y., Tudela D., Pombeiro A.J.L. Metal-ion assisted reactions of oximes and reactivity of oxime-containing metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1996;156:333–362. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kukushkin V.Y., Pombeiro A.J.L. Oxime and oximate metal complexes: unconventional synthesis and reactivity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999;181:147–175. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kukushkin V.Y., Pakhomova T.B., Kukushkin Y.N., Herrmann R., Wagner G., Pombeiro A.J.L. Iminoacylation. 1. Addition of Ketoximes or Aldoximes to Platinum(IV)-Bound Organonitriles. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:6511–6517. doi: 10.1021/ic9807745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner G., Pombeiro A.J.L., Kukushkin Y.N., Pakhomova T.B., Ryabov A.D., Kukushkin V.Y. Iminoacylation: 2. Addition of alkylated hydroxylamines via oxygen to platinum(IV)-bound nitriles. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1999;292:272–275. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner G., Pombeiro A.J.L., Bokach N.A., Kukushkin V.Y. Facile rhenium(IV)-mediated coupling of acetonitrile and oximes. Dalton Trans. 1999:4083–4086. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Kukushkin V.Y., Pakhomova T.B., Bokach N.A., Wagner G., Kuznetsov M.L., Galanski M., Pombeiro A.J.L. Formation of platinum(IV)-based metallaligands due to facile one-end addition of vic-dioximes to coordinated organonitriles1-3. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:216–225. doi: 10.1021/ic990552m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pavlishchuk V.V., Kolotilov S.V., Addison A.W., Prushan M.J., Butcher R.J., Thompson L.K. Mono- and trinuclear nickel(II) complexes with sulfur-containing oxime ligands: Uncommon templated coupling of oxime with nitrile. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1759–1766. doi: 10.1021/ic981277r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith A.G., Tasker P.A., White D.J. The structures of phenolic oximes and their complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003;241:61–85. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontecave M., Pierre J.L. Oxidations by copper metalloenzymes and some biomimetic approaches. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1998;170:125–140. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Nam W. Dioxygen activation by metalloenzymes and models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:465. [Google Scholar]; (b) Korendovych I.V., Kryatov S.V., Rybak-Akimova E.V. Dioxygen activation at non-heme iron: insights from rapid kinetic studies. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:510–521. doi: 10.1021/ar600041x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rolff M., Schottenheim J., Decker H., Tuczek F. Copper–O2 reactivity of tyrosinase models towards external monophenolic substrates: molecular mechanism and comparison with the enzyme. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4077–4098. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00202j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierpoint W.S. o-Quinones formed in plant extracts. Their reactions with amino acids and peptides. Biochem. J. 1969;112:609–616. doi: 10.1042/bj1120609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Que L., Tolman W.B. Biologically inspired oxidation catalysis. Nature. 2008;455:333–340. doi: 10.1038/nature07371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koval I.A., Belle C., Selmeczi K., Philouze C., Saint-Aman E., Schuitema A.M., Gamez P., Pierre J.L., Reedijk J. Catecholase activity of a μ-hydroxodicopper(II) macrocyclic complex: structures, intermediates and reaction mechanism. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2005;10:739–750. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koval I.A., Gamez P., Belle C., Selmeczi K., Reedijk J. Synthetic models of the active site of catechol oxidase: mechanistic studies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;35:814–840. doi: 10.1039/b516250p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Sreenivasulu B., Vetrichelvan M., Zhao F., Gao S., Vittal J.J. Copper(II) complexes of Schiff-Base and reduced Schiff-Base ligands: Influence of weakly coordinating sulfonate groups on the structure and oxidation of 3,5-DTBC. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005:4635–4645. [Google Scholar]; (b) Neves A., Rossi L.M., Bortoluzzi A.J., Szpoganicz B., Wiezbicki C., Schwingel E., Haase W., Ostrovsky S. Catecholase activity of a series of dicopper(II) complexes with variable Cu−OH(phenol) moieties. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:1788–1794. doi: 10.1021/ic010708u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rey N.A., Neves A., Bortoluzzi A.J., Pich C.T., Terenzi H. Catalytic promiscuity in biomimetic systems: Catecholase-like activity, phosphatase-like activity, and hydrolytic DNA cleavage promoted by a new dicopper(II) hydroxo-bridged complex. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:348–350. doi: 10.1021/ic0613107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhardwaj V.K., Aliaga-Alcalde N., Corbella M., Hundal G. Synthesis, crystal structure, spectral and magnetic studies and catecholase activity of copper (II) complexes with di-and tri-podal ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2010;363:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawson D.M., Ke Z., Mack F.M., Doyle R.A., Bignami G.P.M., Smellie I.A., Bühl M., Ashbrook S.E. Calculation and experimental measurement of paramagnetic NMR parameters of phenolic oximate Cu(ii) complexes. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:10512–10515. doi: 10.1039/c7cc05098d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SMART (V 5.628), SAINT (V 6.45a) XPREP, SHELXTL, Bruker AXS Inc.; Madison, WI: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheldrick G.M. University of Gottingen; Germany: 2002. SADABS (Version 2.03) [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Sheldrick G.M., SHELXS-97 A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;A64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Spek A.L. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. 2009;D65:148–155. doi: 10.1107/S090744490804362X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez-Diéguez A., Salinas-Castillo A., Galli S., Masciocchi N., Gutiérrez- Zorrilla J.M., Vitoria P., Colacio E. Synthesis, X-ray structures and luminescence properties of three multidimensional metal–organic frameworks incorporating the versatile 5-(pyrimidyl)tetrazolato bridging ligand. Dalton Trans. 2007:1821–1828. doi: 10.1039/b618981d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parr R.G., Yang W. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1989. Density Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cossi M., Rega N., Scalmani G., Barone V. Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comput. Chem. 2003;24:669–681. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becke A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee W., Yang W., Parr R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1998;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauernschmitt R., Ahlrichs R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996;256:454–464. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H.P., Izmaylov A.F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J.L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery J.A., Jr., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J.J., Brothers E., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J.C., Iyengar S.S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J.M., Klene M., Knox J.E., Cross J.B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R.E., Yazyev O., Austin A.J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V.G., Voth G.A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J.J., Dapprich S., Daniels A.D., Farkas Ö., Foresman J.B., V Ortiz J., Cioslowski J., Fox D.J. Gaussian Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2009. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Boyle N.M., Tenderholt A.L., Langner K.M. cclib: a library for package-independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:839–845. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee A. Building upon supramolecular synthons: Some aspects of crystal engineering. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015;15:3076–3085. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janiak C. A critical account on π–π stacking in metal complexes with aromatic nitrogen-containing ligands. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2000;21:3885–3896. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lever A.B.P. second ed. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1984. Inorganic Electronic Spectroscopy; p. 863. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konar S., Saha U., Dolai M., Chatterjee S. Synthesis of 2D polymeric dicyanamide bridged hexa-coordinated Cu(II) complex: Structural characterization, spectral studies and TDDFT calculation. J. Mol. Struct. 2014;1075:286–291. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukherjee J., Mukherjee R. Catecholase activity of dinuclear copper(II) complexes with variable endogenous and exogenous bridge. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2002;337:429–438. [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Solomon E.I., Sundaram U.M., Machonkin T.E. Multicopper oxidases and oxygenases. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2563–2606. doi: 10.1021/cr950046o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Winkler M., Lerch K., Solomon E.I. Competitive inhibitor binding to the binuclear copper active site in tyrosinase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:7001–7003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Zippel F., Ahlers F., Werner R., Haase W., Nolting H.-F., Krebs B. Structural and functional models for the dinuclear copper active site in catechol oxidases: Syntheses, X-ray crystal structures, magnetic and spectral properties, and X-ray absorption spectroscopic studies in solid state and in solution. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:3409–3419. doi: 10.1021/ic9513604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reim J., Krebs B. Synthesis, structure and catecholase activity study of dinuclear copper(II) complexes. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1997:3793–3804. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayad M.I. Synthesis, characterization and catechol oxidase biomimetic catalytic activity of cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes containing N2O2 donor sets of imine ligands. Arabian J. Chem. 2012;9:S1297–S1306. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang C.-T., Vetrichelvan M., Yang X., Moubaraki B., Murray K.S., Vittal J.J. Syntheses, structural properties and catecholase activity of copper(ii) complexes with reduced Schiff baseN-(2-hydroxybenzyl)-amino acids. Dalton Trans. 2004:113–121. doi: 10.1039/b310262a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramadan A.E.-M.M., Ibrahim M.M., Mehasseb I.M.E. New mononuclear copper(I) and copper(II) complexes containing N4 donors; crystal structure and catechol oxidase biomimetic catalytic activity. J. Coordination Chem. 2012;65:2256–2279. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karipcin F., Dede B., Ozmen I., Celik M., Ozkan E. Mono-, trinuclear nickel(II) and copper(II) dioxime complexes: Synthesis, characterization, catecholase and catalase-like activities, DNA cleavage studies. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2014;59:2539–2544. [Google Scholar]