Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the rate of and risk factors for recurrence ovarian endometrioma after conservative surgery in patients aged 40–49 years. This retrospective, single-center study included 408 women between January 2008 and November 2018. All patients underwent ovarian cyst enucleation, were pathologically diagnosed with ovarian endometrioma and were followed up for ≥ 6 months. Recurrence was defined as a cystic mass with diameter ≥ 2 cm detected by sonography. Recurrence rate after conservative surgery and risk factor of recurrence were analyzed. The median follow-up duration after surgery was 32.0 ± 25.9 months (range 6–125 months). Ovarian endometrioma recurred in 34 (8.3%) of included women and median time to recurrence was 22.4 ± 18.2 months. The cumulative recurrences rate at 12, 24, 36, and 60 months were 3.7%, 6.7%, 11.1%, and 16.7%, respectively. Recurrence was correlated with multilocular cysts (p = 0.038), previous surgical history of ovarian endometrioma (p = 0.006) and salpingectomy (p = 0.043), but not use or duration of post-operative medication. In multivariate analysis, large cyst size (> 5.5 cm) was only risk factor for recurrence in this age group. Post-operative medication did not reduce disease recurrence rate, and thus may be administered for endometriosis-associated pain rather than to prevent recurrence in patients aged 40–49 years.

Subject terms: Diseases, Risk factors

Introduction

Ovarian endometrioma is one of the most common benign gynecologic diseases with an estimated incidence of 10–20% in women of reproductive age1. Ovarian endometrioma is most prevalent in women between 40 and 44 years, and the incidence of this disease tends to decrease after menopause2.

Conservative surgery is the standard treatment for ovarian endometrioma. However, the recurrence rate after conservative laparoscopic surgery is high3, having been reported to be 21.5% at 2 years post-surgical and 40–50% at 5 years post-surgical among all age groups4. Moreover, after second-line conservative laparoscopic surgery, cumulative recurrence rates were reported to be 13.7% at 2 years post-surgical and 37.5% at 5 years post-surgical5. Therefore, additional medical treatments are recommended in addition to conservative surgery to prevent or delay the recurrence of ovarian endometrioma.

In 2014, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) recommended ovarian cystectomy rather than drainage and coagulation of endometriosis in cases of surgical treatment, since ovarian cystectomy can effectively reduce endometriosis-associated pain and has a lower disease recurrence rate6,7. Since the two primary symptoms of endometriosis are pain and infertility, ESHRE guidelines recommend the use of post-operative hormonal therapy for at least 18 to 24 months for secondary disease prevention in women not immediately seeking conception, as well as for the prevention of endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea8.

However, there are limitations to post-operative medication in older women (40–49 years). Various medical conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, thromboembolic disease, cardiovascular problems, and osteoporosis are more frequent in this group than in younger women. Moreover, no age-based drug administration guidelines exist, and few studies have investigated the recurrence rate of ovarian endometrioma in women aged 40–49 years or differences in recurrence rates according to post-operative medication9,10.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the recurrence rates of ovarian endometrioma and the factors affecting recurrence in women aged 40–49 years. We also aimed to determine whether post-operative hormonal medication reduces disease recurrence in this age group.

Methods

Patient population and data collection

All processes conducted in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. We retrospectively reviewed data from patients aged 40–49 years and treated with conservative surgery for ovarian endometrioma from January 2008 to November 2019. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board on the CHA Gangnam Medical Center (GCI-19–36). Institutional Review Board on the CHA Gangnam Medical Center waived the need for informed consent as part of their study approval. In this study, total 22 surgeons were included. All of them were experienced surgeons with more than 300 cases of experience of laparoscopic surgeries and more than 100 cases of laparotomies. The surgical procedure was as follows: first, exfoliated around the endometrioma to enable mobilization. A sharp cortical incision was made on the anti-mesenteric border, and a cleavage plane was identified by sharp- or hydro-dissection. After the entire cyst was removed, the ovarian bed and additional endometriosis of peritoneum and ovarian fossa was fulgurated by bipolar electrocautery.

Patients were included in the study based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) pathologically confirmed ovarian endometriosis; (2) followed up at least six months after surgery; and (3) ultrasonography performed in order to determine recurrence of ovarian endometrioma after surgery. All patients were offered clinical follow-up at intervals ranging from 3 to 12 months or when medical evaluation was needed. At every follow-up visit, a transvaginal/transrectal sonography (TVS/TRS) examination was performed, and symptoms, medical treatment, and clinical data were recorded.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who underwent oophorectomy; (2) patients who were diagnosed with associated gynecologic malignancy; (3) patients with revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification I or II; (4) patients with subsequent pregnancy after surgery; or 5) menopausal status at the time of surgery.

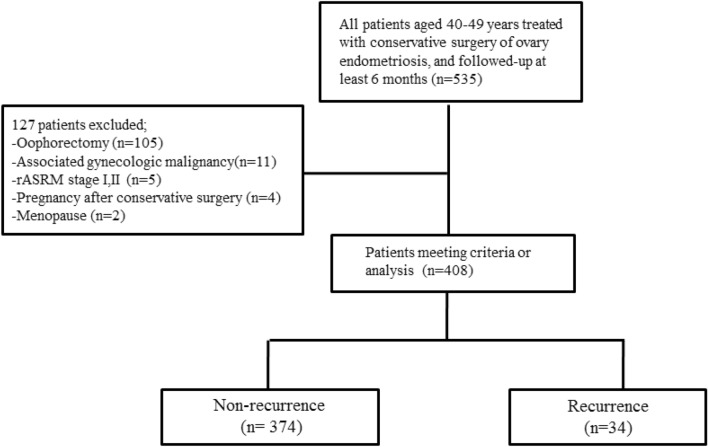

Initially, 535 patients were screened. Among them, 127 patients were excluded based on the above criteria, and a total of 408 patients were selected for this study (Fig. 1). The medical charts of all patients were reviewed to collect data on demographics, age at surgery, body mass index, gravidity, parity, serum cancer antigen 125 (CA125) levels, size of the endometrioma, rASRM stage, use of post-operative medications, and time to disease recurrence.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection process.

Definition of recurrence

Recurrence of ovarian endometrioma was defined when TVS or TRS indicated the presence of a cystic mass with a minimum diameter of 20 mm, thick walls, irregular margins, homogenous low echogenic fluid content with scattered internal echoes, and the absence of papillary proliferations11. If a patient had two endometriomas that were < 20 mm, and the sum of their diameters was > 20 mm, the patient was considered to have recurrent ovarian endometrioma.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS Chicago, IL, USA). The Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for analysis of categorical variables. Quantitative variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate the cumulative probability of recurrence, and the comparison between the curves was performed using the log-rank test. Multivariate modeling using Cox’s proportional hazards models, including the significant variables in univariate analysis, were used to obtain a subset of independent risk factors of recurrent ovarian endometrioma, and among these variables, those with p value < 0.2 underwent multivariate regression analyses. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board on the CHA Gangnam Medical Center (GCI-19-36).

Informed consent

Informed consent was not sought as a retrospective study design was used. Data were anonymized and de-identified before analysis, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 408 patients were included in this study. The median follow-up duration after surgery was 32.0 months (range 6–125 months). The baseline clinical and surgical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. At the time of conservative surgery, the mean age of the patients was 42.7 years. Forty-seven (11.5%) patients had a history of previous surgery for ovarian endometrioma. Of the 408 patients, 339 (83.1%) received post-operative medication on the basis of individual characteristics, and 172 (42.2%) patients were treated with post-operative medication for more than 12 months. The median duration of medication was 15.4 ± 17.3 months (range 0–111 months).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with 40–49 years (n = 408).

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD (range), or n(%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.7 ± 2.3 (42, 40–49) |

| Gravidity | 1.6 ± 1.4 (2, 0–6) |

| Parity | 1.1 ± 0.9 (1, 0–3) |

| Nulliparity | 150 (36.8%) |

| Weight (kg) | 57.5 ± 8.5 (56, 40–92) |

| Height (cm) | 160.7 ± 5.1 (160, 146.8–175.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.3 ± 3.1 (21.5, 15.3–36.7) |

| Tumor size (cm) | 5.9 ± 3.0 (5.5, 0.9–15.4) |

| Cyst character | |

| Unilocular | 260 (63.7%) |

| Multilocular | 148 (36.3%) |

| CA125 (U/mL) (n = 349) | 71.4 ± 82.9 (48.1,7.26–1017) |

| AMH (ng/mL) (n = 183) | 0.96 ± 1.12 (0.56, 0.03–8.02) |

| rASRM Stage | |

| III | 175 (42.9%) |

| IV | 233 (57.1%) |

| Main symptom | |

| Pain | 230 (56.4%) |

| Compression symptom | 6 (1.5%) |

| Bleeding | 46 (11.3%) |

| Infertility | 5 (1.2%) |

| Growing ovarian cyst | 25 (6.1%) |

| Incidentally detected | 96 (23.5%) |

| Laterality | |

| Unilateral | 293 (71.8%) |

| Bilateral | 115 (28.2%) |

| Cul-de-sac obliteration | |

| None | 107 (26.2%) |

| Obliterated | 301 (73.8%) |

| Previous surgical history of ovarian endometrioma | |

| No | 361 (88.5%) |

| Yes | 47 (11.5%) |

| Extent of surgery: uterus | |

| Uterus preservation | 327 (80.1%) |

| Hysterectomy | 81 (19.9%) |

| Extent of surgery: tube | |

| No | 319 (78.2%) |

| One tube | 33 (8.1%) |

| Both tubes | 56 (13.7%) |

| Associated myoma or adenomyosis | |

| No | 79 (19.4%) |

| Yes | 329 (80.6%) |

| Surgical method | |

| Laparoscopy or robotic surgery | 377 (92.4%) |

| Explo-laparotomy | 31 (7.6%) |

| Postoperative medical treatment | |

| No | 69 (16.9%) |

| Yes | 339 (83.1%) |

| Duration of medical treatment | |

| No medication | 69 (16.9%) |

| > 0 ~ ≤ 6Mo | 74 (18.1%) |

| > 6 ~ ≤ 12Mo | 93 (22.8%) |

| > 12 ~ ≤ 24Mo | 106 (26.0%) |

| > 24 ~ ≤ 36Mo | 26 (6.4%) |

| > 36Mo | 40 (9.8%) |

| Median time of medical treatment (month) | 15.4 ± 17.3 (11, 0–111) |

| Recurrent ovarian endometrioma (≥ 2 cm) | |

| No | 374 (91.7%) |

| Yes | 34 (8.3%) |

| Follow-up duration (month) | 32.0 ± 25.9 (23, 6–125) |

| Median time to recurrence(month) (n = 34) | 22.4 ± 18.2 (19.5, 3–76) |

| Median time to reoperation in recurrent case (month) (n = 11) | 34.0 ± 14.0 (37, 12–55) |

BMI, body mass index; CA125, cancer antigen 125; AMH, anti-Mullerian hormone; rASRM, revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine; Mo, month.

The type and duration of post-operative medication was chosen on the basis of individual characteristics The most commonly used post-operative medication was oral progestin in 223 patients (54.7%): oral progestin only in 124 patients and combined with other medications in 99 patients. GnRH agonist was used in 145 patients (35.5%): GnRH only in 38 (9.3%) and combined with other medication in 107 patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Types of post-operative medications (n = 408).

| Types of post-operative medications | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| GnRH agonist | 38 (9.3%) |

| GnRH agonist + oral progestin | 41 (10.0%) |

| GnRH agonist + oral progestin + OC | 8 (2.0%) |

| GnRH agonist + oral progestin + OC + progestin IUD | 1 (0.2%) |

| GnRH agonist + oral progestin + progestin IUD | 8 (2.0%) |

| GnRH agonist + OC | 22 (5.4%) |

| GnRH agonist + OC + progestin IUD | 2 (0.5%) |

| GnRH agonist + progestin IUD | 25 (6.1%) |

| Oral progestin | 124 (30.4%) |

| Oral progestin + OC | 23 (5.6%) |

| Oral progestin + progestin IUD | 18 (4.4%) |

| OC | 10 (2.5%) |

| OC + progestin IUD | 3 (0.7%) |

| Progestin IUD | 16 (3.9%) |

| No medication | 69 (16.9%) |

| GnRH (multiple choices) | 145 (35.5%) |

| Oral progestin (multiple choices) | 223 (54.7%) |

| OC (multiple choices) | 68 (16.7%) |

| Progestin IUD (multiple choices) | 72 (17.6%) |

| No medication | 69 (16.9%) |

GnRH agonist, gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonist; OC, oral contraceptives; IUD, intrauterine device.

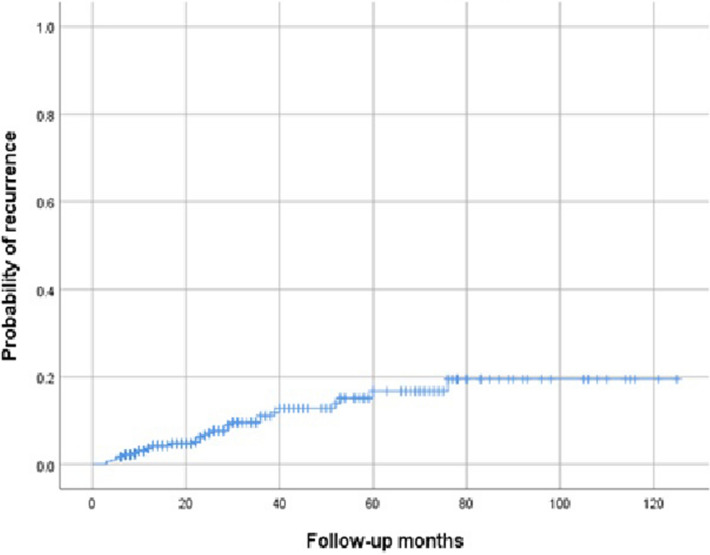

Recurrence rate and characteristics of recurrence cases

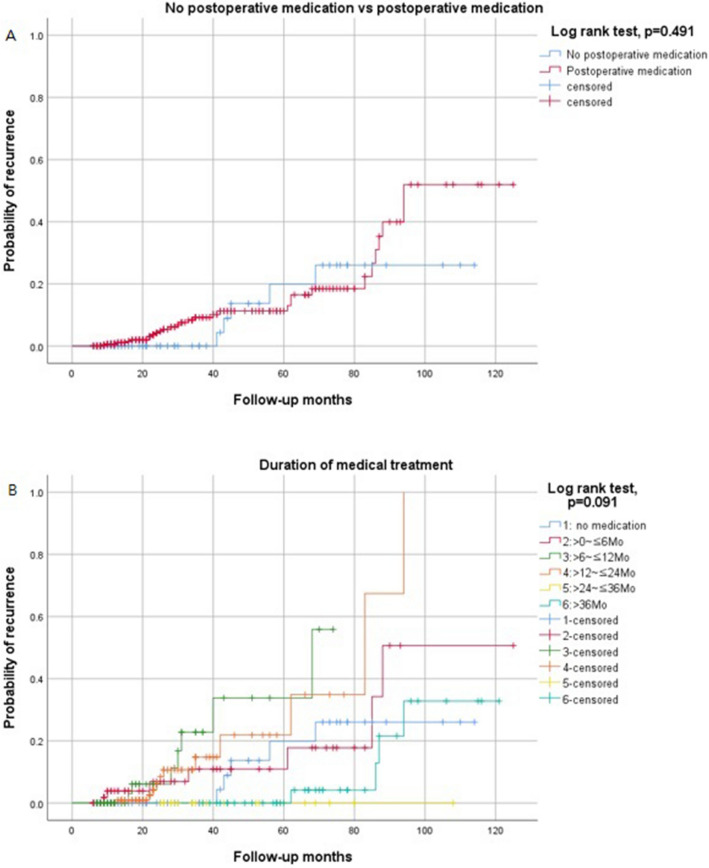

Following the given definition of recurrence, 34 (8.3%) patients experienced recurrent ovarian endometrioma. Excluding one of 34 patients who experienced recurrent endometrioma, follow-up was performed, and 11 (2.7%) patients underwent subsequent surgical intervention. The baseline patient characteristics of the recurrence cases are shown in Table 3. The median time to recurrence was 22.4 months (range 3–76 months). The cumulative recurrence rates at 12, 24, 36, and 60 months after conservative surgery were 3.7%, 6.7%, 11.1%, and 16.7%, respectively (Fig. 2). There were statistically significant differences between the recurrence group and the non-recurrence group in tumor size (7.3 ± 3.7 versus 5.8 ± 2.9 cm, p = 0.041), cyst characteristics (unilocular versus multilocular, p = 0.041), initial CA125 level (99.3 ± 79.4 versus 68.8 ± 82.9 U/mL, p = 0.037), and history of previous surgery for ovarian endometrioma (p = 0.009). However, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the use of post-operative medication or the duration of medical treatment (Table 3). The Kaplan–Meier curve also showed no statistically significant differences in the use of post-operative medication (Fig. 3A) and duration of medical treatment (Fig. 3B) by log-rank test.

Table 3.

Analysis of possible risk factors for recurrent ovarian endometrioma (n = 408).

| Covariable | Nonrecurrent (n = 374) | Recurrent (n = 34) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 42.7 ± 2.4 (42, 40–49) | 42.3 ± 2.0 (42, 40–47) | 0.481 |

| Age groupb | 0.508 | ||

| 40–44 | 297 (79.4%) | 29 (85.3%) | |

| 45–49 | 77 (20.6%) | 5 (14.7%) | |

| Graviditya | 1.5 ± 1.4 (2, 0–6) | 1.6 ± 2.0 (2, 0–6) | 0.877 |

| Paritya | 1.1 ± 1.0 (1, 0–3) | 1.0 ± 0.9 (1, 0–3) | 0.504 |

| Nulliparityb | 138 (36.9%) | 12 (35.3%) | 1.000 |

| Weight (kg)a | 57.5 ± 8.4 (56.1, 40–87.6) | 58.1 ± 9.8 (55.6, 46–92) | 0.960 |

| Height(cm)a | 160.6 ± 5.1 (160, 146.8–175.5) | 162.1 ± 5.6 (160.2, 154–175) | 0.089 |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 22.3 ± 3.1 (21.6, 15.3–36.7) | 22.1 ± 3.4 (21.0, 18.6–32.1) | 0.349 |

| Tumor size (cm)a | 5.8 ± 2.9 (5.4, 0.9–15.3) | 7.3 ± 3.7 (6.3, 2.0–15.4) | 0.041 |

| Cyst characterb | 0.041 | ||

| Unilocular | 244 (65.2%) | 16 (47.1%) | |

| Multilocular | 130 (34.8%) | 18 (52.9%) | |

| CA125(U/mL) (n = 349)a | 68.8 ± 82.9 (46.4, 7.26–1017.0) (n = 321) | 99.3 ± 79.4 (72.5, 10.1–281.7) (n = 29) | 0.037 |

| AMH (ng/mL) (n = 183)a | 0.92 ± 1.12 (0.54, 0.03–8.02) (n = 164) | 1.24 ± 1.12 (0.85, 0.06–3.49) (n = 19) | 0.170 |

| rASRM stageb | 0.106 | ||

| III | 165 (44.1%) | 10 (29.4%) | |

| IV | 209 (55.9%) | 24 (70.6%) | |

| Main symptomsc | 0.500 | ||

| Pain | 209 (55.9%) | 21 (61.8%) | |

| Compression symptom | 6 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Bleeding | 42 (11.2%) | 4 (11.8%) | |

| Infertility | 5 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Growing ovarian cyst | 21 (5.6%) | 4 (11.8%) | |

| Incidentally detected | 91 (24.3%) | 5 (14.7%) | |

| Lateralityb | 0.327 | ||

| Unilateral | 271 (72.5%) | 22 (64.7%) | |

| Bilateral | 103 (27.5%) | 12 (35.3%) | |

| Cul-de-sac obliterationb | 0.222 | ||

| None | 102 (27.3%) | 5 (14.7%) | |

| Partial | 91 (24.3%) | 8 (23.5%) | |

| Complete | 181 (48.4%) | 21 (61.8%) | |

| Previous surgical history of ovarian endometriomab | 0.009 | ||

| No | 336 (89.8%) | 25 (73.5%) | |

| Yes | 38 (10.2%) | 9 (26.5%) | |

| Extent of surgery: Uterusb | 1.000 | ||

| Uterus preservation | 300 (80.2%) | 27 (79.4%) | |

| Hysterectomy | 74 (19.8%) | 7 (20.6%) | |

| Extent of surgery: Tubec | 0.286 | ||

| No | 293 (78.3%) | 26 (76.5%) | |

| One tube | 32 (8.6%) | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Both tube | 49 (13.1%) | 7 (20.6%) | |

| Associated myoma or adenomyosisb | 1.000 | ||

| No | 73 (19.5%) | 6 (17.6%) | |

| Yes | 301 (80.5%) | 28 (82.4%) | |

| Surgical methodb | 0.312 | ||

| Laparoscopy or Robotic | 347 (92.8%) | 30 (88.2%) | |

| Explo-laparotomy | 27 (7.2%) | 4 (11.8%) | |

| Postoperative medical treatmentb | 0.628 | ||

| No | 62 (16.6%) | 4 (11.8%) | |

| Yes | 312 (83.4%) | 30 (88.2%) | |

| Duration of medical treatmentc | 0.639 | ||

| No medication | 64 (17.1%) | 5 (14.7%) | |

| > 0 ~ ≤ 6Mo | 67 (17.9%) | 7 (20.6%) | |

| > 6 ~ ≤ 12Mo | 86 (23.0%) | 7 (20.6%) | |

| > 12 ~ ≤ 24Mo | 95 (25.4%) | 11 (32.3%) | |

| >24~ ≤ 36 Mo | 26 (7.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| > 36 Mo | 36 (9.6%) | 4 (11.8%) | |

| Median time of medical treatment (month)a | 15.4 ± 17.3 (11, 0–111) | 16.3 ± 17.9 (12, 0–66) | 0.815 |

BMI, body mass index;CA125, cancer antigen 125; AMH, anti-Mullerian hormone; rASRM, revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine; Mo, month.

aMann-Whitney U test.

bFisher’s exact test.

cChi-square test.

Figure 2.

Cumulative recurrence of endometrioma after conservative ovarian cyst enucleation in women with 40–49 years.

Figure 3.

Probability of recurrence by Kaplan- Meire curve (Log-rank test) (A). no medication vs. postoperative medication (B). Duration of medican treatment.

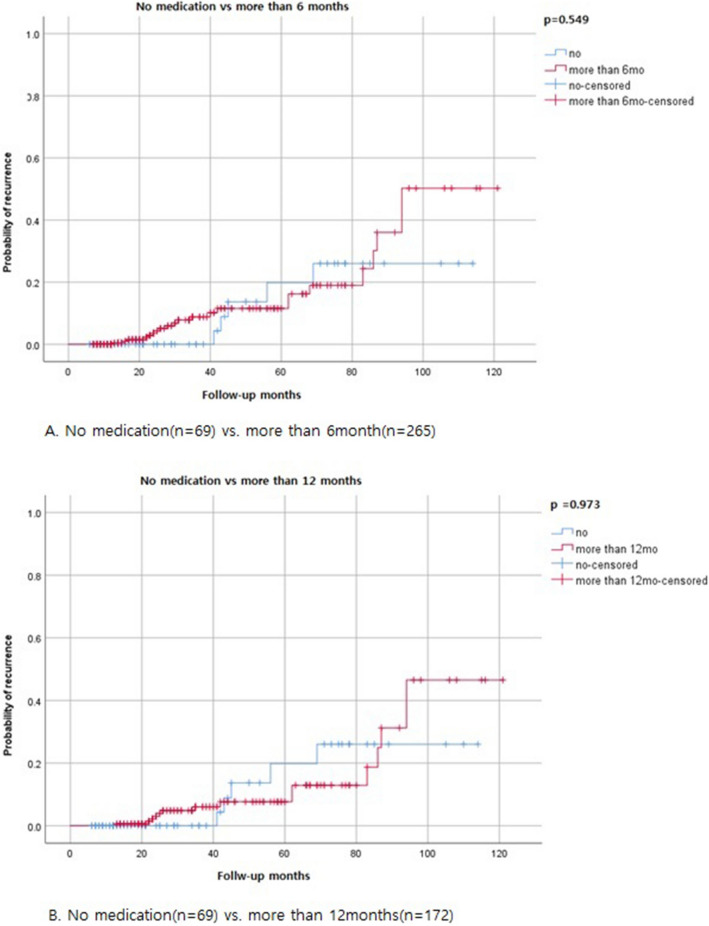

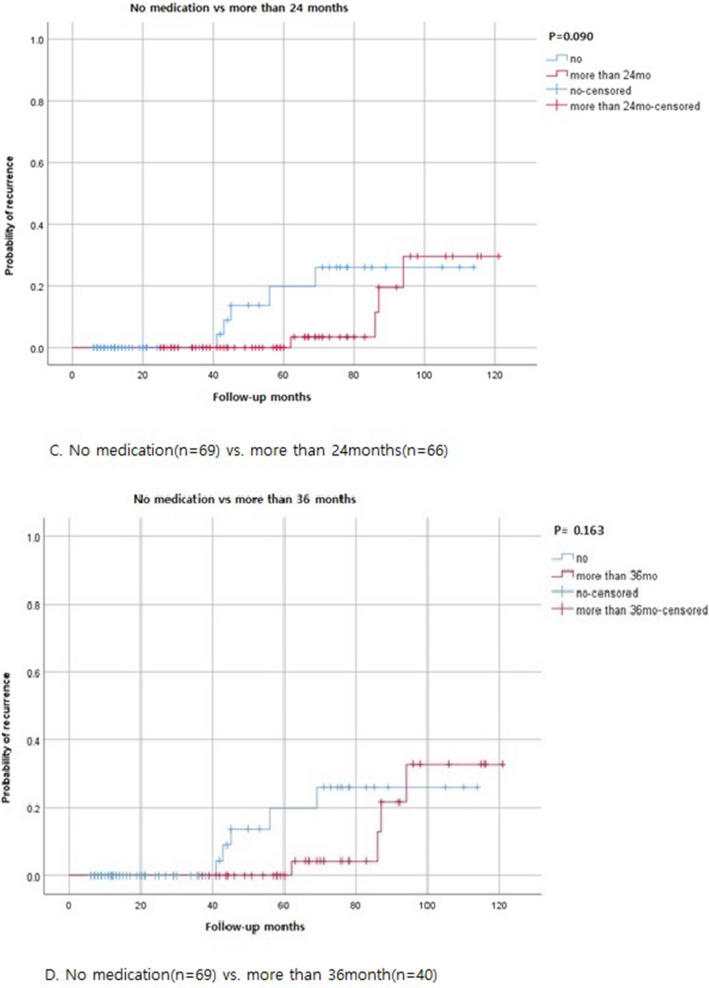

In this study, sub-analysis was performed according to the duration of hormonal therapy after conservative surgery (Fig. 4) In subgroup analysis, there are no significant differences of recurrence rate. (no medication group vs. more than 6mo (months) medication group; p = 0.549, no medication group vs. more than 12mo medication group; p = 0.973, no medication group vs. more than 24mo medication group; p = 0.090, no medication group vs. more than 36mo medication group; p = 0.163).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of recurrence rates in no medication vs duration of medications. (Log-rank test).

Univariate and multivariate analysis for recurrence

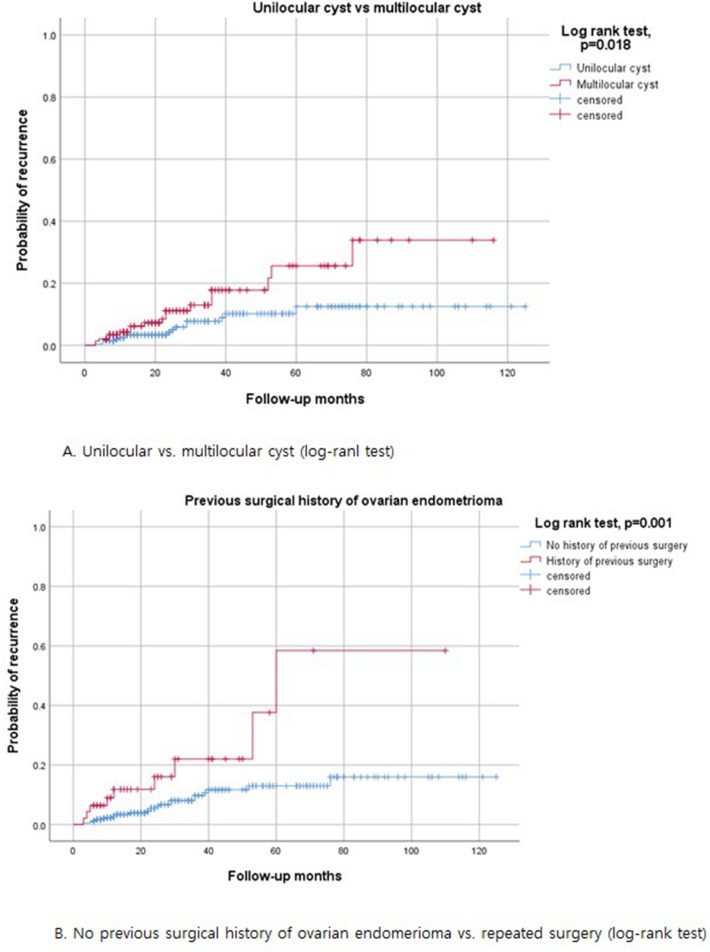

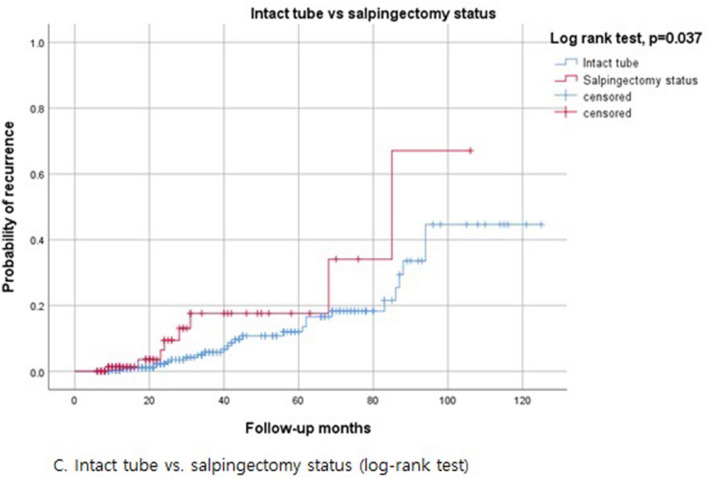

Cox regression analysis was performed on the univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factor for post-operative recurrence of ovarian endometriosis in patients 40–49 years of age (Table 4). According to the univariate analysis, recurrence was correlated with multilocular cysts (p = 0.030) and a previous surgical history of ovarian endometrioma (p = 0.001), and salpingectomy (p = 0.043). Log-rank tests also showed statistical significance with a higher recurrence rate in patients with multilocular cysts (p = 0.018) and a previous surgical history of ovarian endometrioma (p = 0.001), and salpingectomy (p = 0.037) (Fig. 5). The recurrence rate was not correlated with tumor size, initial CA125 level, post-operative medication, or duration of post-operative medication. Using multivariate analysis by Cox regression analysis, tumor size (> 5.5 cm) was only risk factor for disease recurrence in patients aged 40–49 years (p = 0.040).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for independent risk factors of recurrent ovarian endometrioma by Cox proportional hazards models (n = 408).

| Characteristics | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors of recurrence | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Age > 42 years | 1.204 (0.600–2.415) | 0.601 | ||

| Gravidity > 2 | 0.901 (0.392–2.073) | 0.806 | ||

| Parity > 1 | 0.501 (0.239–1.053) | 0.068 | 0.574 (0.248–1.325) | 0.193 |

| Weight > 56 kg | 0.925 (0.466–1.834) | 0.823 | ||

| Height > 160.7 cm | 1.030 (0.525–2.021) | 0.930 | ||

| BMI > 21.5 kg/m2 | 0.811 (0.409–1.609) | 0.549 | ||

| Tumor size > 5.5 cm | 1.958 (0.967–3.965) | 0.062 | 2.462 (1.040–5.830) | 0.040 |

| Multilocular (vs unilocular) | 2.110 (1.074–4.143) | 0.030 | 1.349 (0.602–3.026) | 0.468 |

| CA125 > 48.1U/mL (n = 349) | 2.019 (0.950–4.293) | 0.068 | 1.521 (0.640–3.612) | 0.342 |

| AMH > 0.56 ng/mL (n = 183) | 0.974 (0.368–2.576) | 0.957 | ||

| rASRM stage IV (vs III) | 1.742 (0.830–3.657) | 0.142 | 0.740 (0.247–2.219) | 0.591 |

| Pain symptom (vs no pain symptom) | 0.605 (0.302–1.215) | 0.509 | ||

| Bilateral (vs unilateral) | 1.491 (0.736–3.018) | 0.267 | ||

| CDS obliteration (vs no) | 1.929 (0.743–5.004) | 0.177 | 2.014 (0.492–8.248) | 0.330 |

| Incomplete surgery (vs complete) | 0.586 (0.264–1.299) | 0.188 | 0.559 (0.230–1.356) | 0.198 |

| Previous surgical history of ovarian endometrioma (vs no) | 3.890 (1.805–8.385) | 0.001 | 2.378 (0.896–6.313) | 0.082 |

| Hysterectomy (vs uterus preservation) | 1.581 (0.686–3.644) | 0.282 | ||

| Salpingectomy (vs no) | 2.294 (1.027–5.125) | 0.043 | 2.008 (0.686–5.873) | 0.203 |

| Associated myoma/adenomyosis (vs no) | 1.423 (0.583–3.472) | 0.439 | ||

| Explo-laparotomy (vs laparoscopic or robotic) | 0.819 (0.281–2.388) | 0.715 | ||

| Postoperative medication (vs no) | 1.393 (0.538–3.603) | 0.495 | ||

| Duration of medication > 11Mo (vs ≤ 11Mo) | 0.782 (0.398–1.536) | 0.475 | ||

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; CA125, cancer antigen 125; AMH, anti-Mullerian hormone; rASRM, revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine; CDS, cul-de-sac; d/t, due to; endo, endometriosis; Mo, month.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meire curve of 3 possible risk factors for recurrent endometrioma on univariate analysis.(Log-rank test).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the recurrence of ovarian endometrioma in patients aged 40–49 years and to analyze the risk factors for recurrence, especially the use of post-operative medication, in this age group. The cumulative recurrence rates of ovarian endometrioma reported herein were relatively low compared to the meta-analysis by Guo, which showed recurrence rates of 21.5% and 40–50% at 24 and 60 months after conservative surgery, respectively4. In our study, the only risk factor for recurrence of ovarian endometrioma in this age group was large cyst size (cyst size > 5.5 cm). Two previous studies reported the recurrence rates of ovarian endometrioma in women aged 40–49 years. He et al. reported that the cumulative recurrence rate was 10.0% at 1 year and 27% at 5 years after surgery in patients aged 45 years higher, and that the risk of recurrence was reduced with post-operative treatment and increased by ovarian preservation9. However, this study included oophorectomized patients and used a different definition of recurrence, as not only sonographic findings but also recurrent pain symptoms and elevated serum CA125 level were considered as signs of disease recurrence9. Therefore, it is difficult to compare these results with the current study.

Seo et al. reported that the cumulative recurrence rate of ovarian endometrioma was 10.2% at 60 months in patients 40–45 years of age. This study also reported no differences in recurrence with or without post-operative medication10, which is consistent with our findings. However, Seo et al. only compared 61 patients, divided into a no medication group (n = 40) and a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist + oral contraceptives (OC) group (n = 21)10. Thus, this study may also not be directly comparable to the current report.

In addition to the above mentioned studies, other reports including randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that post-operative medical treatment markedly reduces the recurrence rate of endometrioma12–17. Therefore, long-term medical treatment to prevent recurrence is routinely recommended8. Post-operative medical treatments including OC, GnRH agonists, and progesterone, commonly used to suppress possible residual lesions due to the estrogen-reducing effects3,18. However, each of these treatments has reported adverse effects. The GnRH agonist affects bone mineral density (BMD); in previous studies, adults lost 5–8% of spine BMD after only 3–6 months of GnRH agonist treatment19–21, and decreased BMD may not return to baseline after cessation of treatment22,23. Therefore, the GnRH agonist is typically combined with add-back therapy and only used as a short-term treatment. Progestin has also been shown to decrease BMD with long-term use. Momoeda et al. reported a 1.6 ± 2.4% and 1.7 ± 2.2% decrease in lumbar BMD at 24 and 52 weeks of dienogest use24. Seo et al. compared OC after 6 months of GnRH agonist with add-back therapy versus dienogest for 24 months and showed that lumbar BMD significantly decreased after the first 6 months in GnRH agonist + OC (3.5%) and dienogest (2.3%), and that there were no differences between the two treatments25. In the GnRH agonist + OC group, BMD increased with time after starting OC, and in the dienogest group, BMD did not decrease further after the first 6 months; therefore, there was no further decease in BMD until 24 months in both groups25. In cases of OC, even in healthy women, the U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use categorized OC as category 2, indicating that the theoretical or proven risks of OC must be considered26. Oral contraceptive is usually contraindicated in women with conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, deep vein thrombosis, diabetes mellitus accompanied by organ failure, gallbladder disease, and other malignant diseases such as breast cancer26, and these diseases are typically increased in older women. Coronary heart disease prevalence in women aged 20–39 years is less than 1%, but after age 40, the percentage increases to greater than 5%27. In clinical practice, patients between ages of 40 and 49 years of age are limited by cardiovascular disease and other conditions when choosing hormonal therapy.

However, the efficacy or necessity of post-operative medication was not extensively investigated in women aged 40 years or higher. Considering the limited previous reports on ovarian endometrioma in women aged 40–49 years, our study provides interesting and novel data for the post-operative management of this patient group.

A major strength of our study is the inclusion of a large cohort of patients. However, this study has several limitations. Due to the retrospective study design, some potential selection biases for post-operative medical treatment may have occurred. The decision of post-operative medical treatment was selected according to the surgeon recommendation and each patient’s preferences. Yet, additional biases were minimized by excluding pregnancy, menopause, and oophorectomy cases, which are known to reduce disease recurrence. Second, all included patients were from a single institution. However, we analyzed a larger number of patients compared to previous studies. Third, disease recurrence was defined on the basis of ultrasound findings and did not reflect pain levels. It is difficult to discriminate the pain caused by other gynecologic diseases, such as myoma or adenomyoma, which were present in 329 (80.6%) of included patients in this study. Therefore, in some cases, we considered the time interval from the start of post-operative medical treatment to when the patients complained of pain after surgery, for cases where less than 2 cm of ovarian endometrioma was indicated by ultrasound. These cases were not included as true recurrence. Fourth, we did not compare types of post-operative medical treatment: GnRH agonist, progestin, OC, or levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Since each patient was treated on a case-by-case basis, the medical treatments were not consistent among cases; therefore, this comparison was difficult in our study group. To overcome these limitations, future large-scale, prospective, observational or comparative studies are required.

In conclusion, the relatively low cumulative recurrence rate of ovarian endometrioma seemed to be in women aged 40–49 years, regardless of post-operative medication use after surgery, and the only risk factor for recurrent ovarian endometrioma was large cyst size (cyst size > 5.5 cm). In this study, we did not confirm the risk reducing effect of recurrence in post-operative medication use, but more research is needed to determine whether post-operative medication use really does not further decrease risk in this age group.

Due to the possible risks and benefits of hormonal treatment, it is possible to omit post-operative medical treatment for the prevention of disease recurrence in this age group with informed consent. However, more research is needed to determine whether post-operative medication use decreases risk of recurrent in this age group.

Author contributions

N.L., S.M., S.W. were involved in the data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing. M.K.K. was involved in the data collection or management, manuscript editing. Y.J.C., M.K. were involved in the statistical analysis. Y.W.J., B.S.Y. were involved in the protocol/project development and manuscript editing. S.J.S. and M.L.K. designed study protocol/project development, supervised manuscript writing and editing. All authors contributed to the interpretation, commented on multiple versions, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No specific funding obtained.

Data availability

Data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. However, the data cannot be made public to maintain women’s privacy and legal reasons as it contains private health information along with identifiers.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Eskenazi B, Warner ML. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 1997;24:235–258. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parazzini F, Esposito G, Tozzi L, Noli S, Bianchi S. Epidemiology of endometriosis and its comorbidities. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017;209:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vercellini P, et al. Postoperative oral contraceptive exposure and risk of endometrioma recurrence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;198(504):e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo SW. Recurrence of endometriosis and its control. Hum Reprod. 2009;15:441–461. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim ML, et al. Recurrence of ovarian endometrioma after second-line, conservative, laparoscopic cyst enucleation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;210(216):e1–6. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004992.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmona F, Martinez-Zamora MA, Rabanal A, Martinez-Roman S, Balasch J. Ovarian cystectomy versus laser vaporization in the treatment of ovarian endometriomas: a randomized clinical trial with a five-year follow-up. Fertil. Steril. 2011;96:251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunselman GA, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014;29:400–412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He ZX, et al. Risk factors for recurrence of ovarian endometriosis in Chinese pateitns aged 45 and over. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2018;131:1308–1313. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.232790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo JW, Lee DY, Yoon BK, Choi D. The age-related recurrence of endometrioma after conservative surgery. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017;208:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mais V, et al. The efficiency of transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of endometrioma. Fertil. Steril. 1993;60:776–780. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seracchioli R, et al. Long-term oral contraceptive pills and postoperative pain management after laparoscopic excision of ovarian endometrioma: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2010;94(2):464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown J, Crawford TJ, Datta S, Prentice A. Oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001019.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vercellini P, et al. Oral contraceptives and risk of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2011;17:159–170. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-term use of dienogest in women with ovarian endometrioma. Reprod. Sci. 2018;25(3):341–346. doi: 10.1177/1933719117725820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rafique S, Decherney AH. Medical management of endometriosis. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;60:485–496. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00519-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song SY, et al. Efficacy of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system as a postoperative maintenance therapy of endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod Biol. 2018;231:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sesti F, et al. Hormonal suppression treatment or dietary therapy versus placebo in the control of painful symptoms after conservative surgery for endometriosis stage III-IV A randomized comparative trial. Fertil. Steril. 2007;88:1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998;91:16–24. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Surrey ES, Judd HL. Reduction of vasomotor symptoms and bone mineral density loss with combined norethindrone and long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy of symptomatic endometriosis: a prospective randomized trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992;75:558–563. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.2.1386374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuo H. Prediction of the change in bone mineral density induced by gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment for endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2004;81:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Revilla R, et al. Evidence that the loss of bone mass induced by GnRH agonists is not totally recovered. Maturitas. 1995;22:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00929-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Surrey ES, Hornstein MD. Prolonged GnRH agonist and add-back therapy for symptomatic endometriosis: long-term follow-up. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;99:709–719. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)01945-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Momoeda M, et al. Long-term use of dienogest for the treatment of endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2009;35:1069–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seo JW, Lee DY, Kim SE, Yoon BK, Choi D. Comparison of long-term use of combined oral contraceptive after gonadotropin-releaseing hormone agonist plus add-back therapy versus dienogest to prevent recurrence of ovarian endometrioma after surgery. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019;236:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tepper NK, Krashin JW, Curtis KM, Cox S, Whiteman MK. Update to CDC’s U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use, 2016: Revised recommendations for the use of hormonal contraception among women at high risk for HIV infection. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017;66:990–994. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6637a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mozaffarian D, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. However, the data cannot be made public to maintain women’s privacy and legal reasons as it contains private health information along with identifiers.