Abstract

Introduction/Objective:

Chronic migraine (CM) is associated with impaired health-related quality of life and substantial socioeconomic burden, but many people with CM are underdiagnosed and do not receive appropriate preventive treatment. OnabotulinumtoxinA and topiramate have demonstrated efficacy (treatment benefit under ideal conditions) for the prevention of headaches in people with CM in clinical trials, but real-world studies suggest markedly different clinical effectiveness (treatment benefit based on a blend of efficacy and tolerability). This study sought to evaluate patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of onabotulinumtoxinA versus topiramate immediate release for people with CM.

Methods:

FORWARD was a prospective, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, open-label, phase 4 study comparing onabotulinumtoxinA 155 U every 12 weeks with topiramate 50 to 100 mg/day for ≤36 weeks in people with CM. PROs measured included the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire Quick Depression Assessment (PHQ-9), Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Specific Health Problem (WPAI:SHP), and Functional Impact of Migraine Questionnaire (FIMQ).

Results:

A total of 282 patients were randomized and treated with onabotulinumtoxinA (n = 140) or topiramate (n = 142). From baseline to week 30, mean HIT-6 test scores improved significantly in patients taking onabotulinumtoxinA compared with topiramate (P < .001). Improvements in depression over time were observed via larger changes in PHQ-9 scores with onabotulinumtoxinA than topiramate (P < .001). Work productivity assessed via WPAI:SHP scores revealed significant improvements with onabotulinumtoxinA versus topiramate in Work Productivity Loss (P = .024) and Activity Impairment (P < .001) domains. Results from the FIMQ also revealed a larger reduction from baseline with onabotulinumtoxinA vs topiramate (P < .0001).

Conclusion:

OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment had more favorable real-world effectiveness than topiramate on depression, headache impact, functioning and daily living, activity, and work productivity. The overall study results suggest that the beneficial effects on a range of PROs are the result of improved effectiveness when onabotulinumtoxinA is used as preventive treatment for CM.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov:

NCT02191579; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02191579

Keywords: onabotulinumtoxinA, topiramate, patient-reported outcome measures, patient health questionnaire, depression, quality of life, migraine disorders, headache, anxiety, activities of daily living, treatment outcome

Introduction

Preventive treatment for migraine, which encompasses episodic migraine and chronic migraine (CM), is recommended to reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks and their associated disability; improve daily functioning; and improve responsiveness to and reduce overuse of acute treatments for migraine attacks.1-3 However, many people with CM are not currently receiving appropriate preventive treatment despite the frequency of their attacks.4,5 CM is a debilitating neurologic disease defined as headaches that occur on ≥15 days per month for >3 months and have migraine features on ≥8 days per month.6 It is associated with substantial individual disability as well as family and societal burden.7-9 Due to frequent migraine attacks, people with CM have reduced health-related quality of life, higher rates of depression and anxiety, greater degrees of lost productivity, increased levels of unemployment, lower socioeconomic status, and increased healthcare resource utilization.7-12

OnabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) was approved13 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2010 and subsequently worldwide for the prevention of headaches in those with CM, and topiramate immediate release (Topamax®) is an FDA-approved14 treatment for migraine that is often prescribed first-line. Both onabotulinumtoxinA and topiramate have demonstrated efficacy across controlled randomized clinical trials for the prevention of CM.15-19 However, data from real-world studies suggest that the clinical effectiveness of these treatments is markedly different as a result of different tolerability profiles, with adverse events (AEs) leading to more treatment discontinuations with topiramate.20 Nevertheless, topiramate is considered a first- or second-line preventive treatment option for migraine, ahead of onabotulinumtoxinA.21 Moreover, based on expert opinion, rather than data from controlled trials, the American Headache Society consensus statement recommends that patients fail other preventive agents before receiving treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA.2

The FORWARD study (NCT02191579) was a prospective, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, open-label study designed to compare the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA and topiramate in adults with CM. Primary endpoints and safety results from the study have been published.22 Given the substantial negative impacts of CM on patient life, this analysis looked beyond the primary outcome of headache day reduction and overall safety of treatments to data that evaluated the impacts of treatments on different aspects of patients’ lives and well-being (ie, patient-reported outcomes [PROs]). For the present prespecified analysis, we assessed headache impact, depression, functioning and daily living, activity, and work productivity to measure the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA compared with topiramate in people with CM.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

The FORWARD trial design and patient inclusion/exclusion criteria have been described previously.22 Briefly, adult patients (aged 18-65 years) with a diagnosis of CM according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (ICHD-3 beta) criteria who had at least 15 headache days during the 28-day run-in period were randomized (1:1) to receive either onabotulinumtoxinA 155 U (31 sites; fixed-site, fixed-dose paradigm across 7 head/neck muscles) at day 1, week 12 ± 7 days, and week 24 ± 7 days or topiramate titrated to 50 to 100 mg/day, in 2 divided doses, over 4 weeks, starting with an initial dose of 25 mg/day for the first week. Both treatments were administered per their approved FDA labels. Patients discontinuing topiramate treatment for any reason on or before week 36 could cross over to receive onabotulinumtoxinA treatment at their next scheduled study visit (ie, week 12, 24, or 36). Patients were required to maintain a daily electronic headache diary (e-diary) during the entire study period.

This study was conducted in compliance with the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice Topic E6, institutional review board (IRB) regulations (US 21 Code of Federal Regulations Part 56.103), and requirements of public registration of clinical trials in the United States (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02191579); the trial was approved at each site by a properly constituted IRB. Prior to administration of the study medication, written informed consent was obtained from each randomized patient.

PRO Outcome Measures

PROs identified in the International Headache Society’s clinical trial treatment guidelines for CM23 and deemed important to people with CM were assessed in FORWARD. These include secondary or exploratory outcomes of headache impact, depression, functioning and daily living, activity, and work productivity. Data were collected via e-diary and electronic clinical outcomes assessments.

The Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) is a validated instrument for assessing the impact of headaches via 6 items: pain, role functioning, social functioning, cognitive functioning, vitality, and psychological distress.24 The total score is the sum of all items and can range from 36 (no impact) to 78 (severe impact). Scores of 36 to 49 are categorized as “little to no impact,” 50 to 55 as “some impact,” 56 to 59 as “substantial impact,” and 60 to 78 as “severe impact.” The HIT-6 was administered on day 1 and at weeks 6, 18, and 30; patients who switched to onabotulinumtoxinA also completed the instrument at week 42.

The Functional Impact of Migraine Questionnaire (FIMQ), previously known as Assessment of Chronic Migraine-Impact,25 is a reliable and valid measure to assess patients with episodic migraine and CM. Content validity and psychometric properties have been demonstrated based on qualitative data from patient interviews and quantitative assessment of measurement properties in patients with migraine. The FIMQ measures patient-relevant impacts of migraine in the past 7 days across 3 domains: activity impairment (14 items), emotional functioning (3 items), and cognitive functioning (3 items). These items are rated on a Likert-type scale of 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time) [1-6 on questionnaire] with 1 item rated on a scale of 0 (none of the time) to 6 (N/A, I do not work) [1-7 on questionnaire]. Individual items are then transformed to a 0 to 100 scale (item response divided by number of possible responses times 100), with higher scores indicating a greater level of migraine impact. The FIMQ total is scored as the mean of nonmissing items, if at least 50% are nonmissing item responses. If more than 50% of item responses are missing, the total score is set to missing. The FIMQ was administered on day 1 and at weeks 6, 18, and 30; patients who switched to onabotulinumtoxinA also completed the instrument at week 42.

The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire Quick Depression Assessment (PHQ-9) is a validated screening and diagnostic tool featuring the 9 diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders in the past 2 weeks from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition.26 Patients are asked to indicate the frequency with which they have been bothered by their symptoms over the previous 2 weeks using a 4-point scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), and 3 (nearly every day). The total score can range from 0 (best) to 27 (worst). A score of 15 to 19 is considered to indicate moderately severe depression and 20 to 27 as severe depression. The PHQ-9 was administered on day 1 and at weeks 12, 24, and 36; patients who switched to onabotulinumtoxinA also completed the instrument at week 48.

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Ques-tionnaire: Specific Health Problem (WPAI:SHP) is a validated instrument for measuring work productivity loss, absenteeism, presenteeism, and activity impairment over the past 7 days because of general health or a specified health problem (http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_SHP.html).27 The WPAI:SHP outcomes are expressed as impairment percentages, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity. The WPAI:SHP was administered on day 1 and at weeks 12, 24, and 36; patients who switched to onabotulinumtoxinA also completed the instrument at week 48.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were provided for continuous variables (mean, SD) and categorical variables (counts, percentages). Changes from baseline in total HIT-6 score and the FIMQ General Impacts domain at week 30, and score changes from baseline for the PHQ-9 and the WPAI:SHP Work Productivity Loss and Activity Impairment scales at week 36 were compared between treatment groups using a nonparametric rank analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with treatment as a factor and adjusting for the baseline value. For all statistical comparisons, P-values of .05 or less were considered statistically significant.

A baseline observation carried forward (BLOCF) method was prespecified to impute missing values for all primary, secondary, and PRO outcome measures. Missing values were replaced with the baseline value. If a patient had a missing value for any reason (eg, discontinuation due to AEs, lost to follow-up, lack of efficacy), baseline data were used (eg, if HIT-6 was missing, then baseline value was used) rather than other imputation methods. Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome were previously undertaken using other imputation approaches including pro-rated observed data and modified last observation carried forward (mLOCF). Neither indicated a significant group difference between treatment groups. Because the FORWARD study aimed to evaluate effectiveness rather than efficacy, the BLOCF approach was selected based on the premise that a treatment that cannot be tolerated is unlikely to be effective in clinical practice, so it was best suited for the primary research objective. This assumption is justified although it arguably conflates lack of efficacy with tolerability. The previously published sensitivity analyses used for primary analyses support the study hypothesis that the 2 treatments evaluated have similar efficacy, as has been demonstrated in other published clinical trials, but have a marked difference in effectiveness, which is largely a function of tolerability. These study analyses aim to further quantify the real-world patient-reported benefit between treatments.22

Results

Patient Disposition and Demographics

A total of 282 patients were randomized to treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA (n = 140) or topiramate (n = 142). Base-line demographics and clinical characteristics, including PRO measures, were similar between the 2 treatment groups (Table 1). Overall, 120 (85.7%) patients treated with onabotulinumtoxinA completed the study. Of patients randomized to topiramate, 28 (19.7%) completed their initial treatment and 80 (56.3%) discontinued topiramate and switched to onabotulinumtoxinA.22

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Patient-Reported Outcomes.

| OnabotulinumtoxinA (n = 140) | Topiramate (n = 142) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 40.2 (11.7) | 39.4 (12.6) |

| Female, n (%) | 117 (84) | 122 (86) |

| White race, n (%) | 111 (79) | 118 (83) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.9 (7.1) | 28.8 (6.5) |

| Use of headache preventive treatments, n (%) | 26 (18.6) | 25 (17.6) |

| HIT-6 scorea | 65.2 (5.3) | 64.4 (5.0) |

| PHQ-9 scoreb | 6.5 (5.0) | 7.6 (5.6) |

| FIMQa | 48.6 (19.8) | 48.6 (20.7) |

| Ability to perform work score | ||

| Absenteeismc | 4.6 (11.6) | 4.2 (8.4) |

| Presenteeism workc | 36.0 (19.2) | 35.0 (15.6) |

| Productivity lossc | 4.8 (2.6) | 5.1 (2.3) |

| Work activity impairmentd | 5.7 (2.3) | 6.3 (2.3) |

| Job/employment, n (%)c | 107 (76.4) | 101 (71.1) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FIMQ, Functional Impact of Migraine Questionnaire; HIT-6, 6-item Headache Impact Test; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire Quick Depression Assessment.

Data are mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

OnabotulinumtoxinA (n = 110); topiramate (n = 115).

OnabotulinumtoxinA (n = 137); topiramate (n = 140).

OnabotulinumtoxinA (n = 107); topiramate (n = 101).

OnabotulinumtoxinA (n = 137); topiramate (n = 139).

In the primary analysis of the FORWARD study, a significantly higher proportion of patients randomized to onabotulinumtoxinA experienced ≥50% reduction in headache frequency at week 32 (primary endpoint) compared with those randomized to topiramate (40% [56/140] vs 12% [17/142], respectively; adjusted OR, 4.9 [95% CI, 2.7-9.1]; P < .001).22 OnabotulinumtoxinA was superior to topiramate in meeting secondary endpoints including frequency of headache days per 28-day period and proportion of patients with ≥70% decrease in headache days.22 AEs were reported by 48% (105/220) of onabotulinumtoxinA and 79% (112/142) of topiramate patients.22

Changes in PROs during the Study Period

Overall Impact of Headache (HIT-6 and FIMQ Total Score)

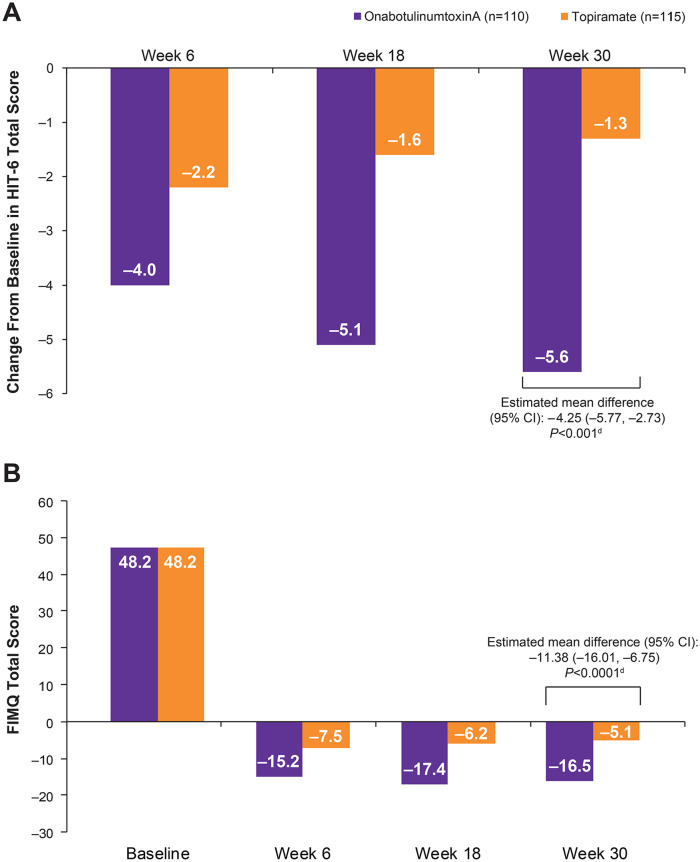

Results demonstrated that the decrease in mean HIT-6 score from baseline to week 30 was significantly greater with onabotulinumtoxinA than with topiramate (mean difference: –4.25 [95% CI: –5.77, –2.73]; P < .001; Figure 1A). These results are consistent with the mean score reduction from baseline at week 30 and significant between-group difference favoring onabotulinumtoxinA (estimated between-treatment difference: –4.2 [95% CI: –5.8, –2.7]; P < .001) published previously.22

Figure 1.

Overall impact of headache. (A) Change from baseline in HIT-6a total scores.b (B) Change from baseline in mean FIMQ total scores.b,c

Abbreviations: BLOCF, baseline observation carried forward; FIMQ, Functional Impact of Migraine Questionnaire; HIT-6, 6-item Headache Impact Test.

aHIT-6 total score categories: little to no impact (36-49), some impact (50-55), substantial impact (total score 56-59), and severe impact (60-78).

bOnly patients with values at both baseline and the specific postbaseline time point (actual or imputed using BLOCF) are included.

cEstimated mean difference, 95% CI, and P value for the final week-30 score are assessed using nonparametric rank analysis of covariance with treatment as a factor and adjusting for baseline.

dP value compares the change from baseline for onabotulinumtoxinA versus topiramate at week 30, assessed using analysis of covariance and adjusting for baseline headache days.

The estimated mean difference in reduction in FIMQ total score from baseline to week 30 was −11.38 (95% CI: –16.01, –6.75) for onabotulinumtoxinA compared with topiramate (P < .0001; Figure 1B). The estimated mean differences in FIMQ domain scores from baseline to week 30 (all P < .0001) were: activity impairment −10.75 (95% CI: –15.38, –6.13); emotional functioning −10.81 (95% CI: –15.76, –5.86); and cognitive functioning −14.49 (95% CI: –19.90, –9.07).

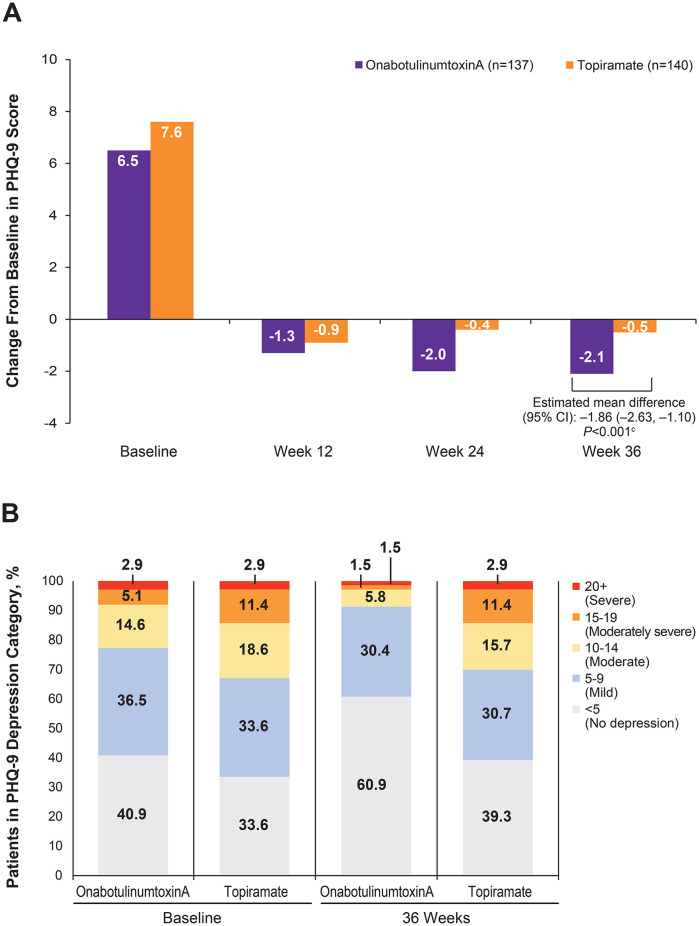

Depression (PHQ-9)

The reduction in mean total score from baseline to week 36 on the PHQ-9 was significantly greater with onabotulinumtoxinA than with topiramate (mean difference: –1.86 [95% CI: –2.63, –1.10]; P < .001; Figure 2A). In addition, 22.6% and 32.9% of patients randomized to receive onabotulinumtoxinA and topiramate, respectively, had depression that scored in the moderate to severe range (PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater) at baseline (Figure 2B). Over the course of the observation period, the percentage of patients with moderate to severe depression at baseline who were treated with onabotulinumtoxinA declined steadily to 8.8% at week 36, while patients treated with topiramate stayed at 30.0%.

Figure 2.

PHQ-9 scores.a,b (A) Change from baseline. (B) Percentage of patients in each depression category (scores ≥10).

Abbreviations: BLOCF, baseline observation carried forward; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire Quick Depression Assessment.

aOnly patients with values at both baseline and the specific postbaseline time point (actual or imputed using BLOCF) are included.

bPHQ-9 scoring: <5, no depression, 5-9, mild; 10-14, moderate; 15-19, moderately severe; 20-27, severe.

cEstimated mean difference, 95% CI, and P value for the week-36 score are assessed using nonparametric rank analysis of covariance with treatment as a factor and adjusting for baseline.

Work Productivity (WPAI:SHP)

Changes from baseline at week 36 favored onabotulinumtoxinA treatment compared with topiramate across domains on the WPAI:SHP. On the Work Productivity Loss domain, there was a significant difference in reduction in impairment score from baseline among patients treated with onabotulinumtoxinA compared with topiramate (difference of −0.67 [95% CI: –1.25, –0.09]; P = .024; Figure 3A). On the Activity Impairment domain, a significantly larger change from baseline was observed among patients treated with onabotulinumtoxinA compared with topiramate (difference of −1.53 [95% CI: –2.07, –1.0]; P < .001; Figure 3B). Both treatments were associated with a slight reduction in mean (standard deviation) absenteeism scores of −1.1 (9.64) and −0.8 (3.76) at week 36 compared with baseline for onabotulinumtoxinA and topiramate, respectively. Mean (standard deviation) presenteeism scores were slightly reduced for onabotulinumtoxinA and slightly increased for topiramate (–2.2 [18.93] vs 1.5 [5.73], respectively) at week 36 compared with baseline.

Figure 3.

WPAI:SHP scores. (A) Work productivity loss domain. (B) Activity impairment domain.a

Abbreviations: BLOCF, baseline observation carried forward; WPAI:SHP, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Specific Health Problem.

aOnly patients with values at both baseline and the specific postbaseline time point (actual or imputed using BLOCF) are included.

bEstimated mean difference, 95% CI, and P value for the final week-36 score are assessed using nonparametric rank analysis of covariance with treatment as a factor and adjusting for baseline.

Discussion

In this study, onabotulinumtoxinA treatment resulted in significantly greater reductions in headache-related impact, activity and work productivity loss, and functional impact as measured by the HIT-6, WPAI:SHP, and FIMQ respectively, compared with the reductions seen with topiramate treatment. OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment was also more effective than topiramate in reducing depression, as measured by the PHQ-9. These findings, combined with the overall results of FORWARD, suggest that the beneficial effects on a range of PROs are likely the result of better effectiveness, a blending of efficacy and tolerability under real-world conditions, compared to topiramate when onabotulinumtoxinA is used as preventive treatment for CM.

Understanding the effect of treatment from a patient’s perspective is critical to ensuring that endpoints in randomized clinical trials correspond to benefits that are important and perceptible to the patient.28 Guidelines for controlled clinical trials in CM29,30 acknowledge the importance of PRO measures, to ensure that treatment options address the significant impact that migraine has on health-related quality of life, disability, mental health, performing daily activities, and work productivity/employment. In addition, the National Institutes of Health and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Initiative support and promote pragmatic clinical trial methodology to obtain information directly relevant for the needs of healthcare providers.31 The patient’s perspective and perception of effectiveness likely contribute to adherence, which is critical to improving outcomes and reducing healthcare resource utilization.32 The FORWARD study used a pragmatic study design to assess the patient’s perspective on the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA compared with topiramate. In current practice, topiramate is often considered first-line treatment prior to onabotulinumtoxinA.21 However, in real-world practice, most patients discontinue topiramate treatment due to tolerability and adherence issues.20,32 Results from our study are consistent with these observations and highlight the patient view that favors the comparative effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA.

The results reported here, which demonstrate the positive impacts of onabotulinumtoxinA treatment on PROs, are consistent with other published findings. The pivotal, randomized, controlled PREEMPT trials demonstrated that onabotulinumtoxinA treatment results in significant and clinically meaningful short- and long-term reductions in headache impact and improvements in health-related quality of life.33,34 In the open-label, 108-week (9 treatment cycles) COMPEL study, treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA was associated with clinically meaningful reductions in comorbid anxiety and depression, similar to the results of the present study.35 Similarly, results from the open-label REPOSE study revealed improvements over a 2-year period in migraine-specific quality of life, assessed using the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire, and the Euro-Qol 5-Dimension questionnaire, which assessed health-related quality of life.36

The primary analysis of FORWARD provided comparative data on the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA and topiramate for treating CM, demonstrating statistically significant differences in favor of onabotulinumtoxinA.22 Results also suggested a superior tolerability profile for onabotulinumtoxinA compared with topiramate based on treatment-related AEs and overall discontinuations,22 which was consistent with a previous clinical study comparing the treatments.20

Some may argue that initial treatment with topiramate may represent a more cost-effective approach to treatment of CM. Given the large proportion of patients who cannot tolerate topiramate, any short-term cost reduction obtained from the delay in initiating treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA may be offset by the cost of delaying the clinically meaningful improvement required to produce a decrease in healthcare resource utilization. A claims-based analysis showed that patients receiving onabotulinumtoxinA had statistically significant reductions compared with oral migraine prophylactic medications (including topiramate) in headache-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and costs.37 Similarly, an analysis from a single university-based subspecialty headache clinic showed that these decreases in healthcare utilization with onabotulinumtoxinA offset a substantial portion of the cost of treatment.38 Additionally, patients were relieved of the physical and emotional burdens associated with trips to the emergency department and/or hospital. Therefore, onabotulinumtoxinA is an effective, well-tolerated, and cost-effective treatment for migraine preventive treatment for CM compared with topiramate.

The FORWARD study had limitations, which have been discussed previously22; the primary concern was the potential bias introduced among patients randomized to topiramate who were able to cross over to onabotulinumtoxinA, which could potentially inflate discontinuation rates with topiramate. However, as discussed previously,22 we believe patients were motivated to give topiramate an adequate trial, which was demonstrated by the mean highest dose achieved of 90.8 mg/day. Although the discontinuation rates with topiramate reported in randomized clinical trials were lower than rates in this study,15,16 discontinuations were consistent with real-world rates for anti-epilepsy medications.39 In addition, the discontinuation rate for onabotulinumtoxinA was also higher in this study than in previous randomized clinical trials.19 Other limitations previously discussed22 include lack of a placebo arm, lack of blinding (patient and investigator), potential bias introduced among patients randomized to topiramate with potential crossover, awareness of potential AEs, and unidirectional crossover design. These limitations also apply to the current analysis using PRO measures. Although alternative study designs were considered to avoid these limitations, the use of a placebo was discounted because of the availability of 2 evidence-based, FDA-approved, effective treatments, and blinding of onabotulinumtoxinA treatments vs oral treatments would be very difficult. Furthermore, when patients discontinued treatment, baseline observations were carried forward, which assumes that a treatment that cannot be tolerated is unlikely to be effective but could conflate a lack of efficacy with tolerability. To control for this, a sensitivity analysis was performed and presented in the primary report,22 which confirmed that the differences between treatments were due to effectiveness, likely resulting from the high discontinuation rates for topiramate observed and consistent in real-world patterns.

Conclusion

Together with the primary efficacy and safety findings reported previously in the FORWARD study, the results reported here demonstrate that onabotulinumtoxinA treatment provides a range of beneficial effects, including reduction in monthly headache days as well as improvements in a number of important PROs, such as impact, functioning and daily living activities, depression, and work productivity and activity. Given the more favorable tolerability profile of onabotulinumtoxinA compared with topiramate, it is suggested that onabotulinumtoxinA treatment improves adherence and persistence in real-world settings, ultimately providing improved effectiveness relative to currently available oral preventive agents such as topiramate. Given the efficacy provided by onabotulinumtoxinA demonstrated in the FORWARD study along with its safety profile and reductions in healthcare utilization, clinicians and/or payers may wish to reconsider delaying treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA until other agents have failed. Clinical research is needed to provide additional data and insights into unfavorable costs of delaying onabotulinumtoxinA treatment for people with CM and its associated burdens.

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Lisa Feder, PhD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, Parsippany, NJ, and was funded by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie). The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors. The authors received no honorarium/fee or other form of financial support related to the development of this article.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Prior presentations: American Headache Society (AHS) 60th Annual Scientific Meeting, June 30, 2018, San Francisco, CA; Diamond Headache Clinic Research & Educational Foundation (DHCREF) Headache Update 2018, July 12–15, 2018, Lake Buena Vista, FL; 17th Migraine Trust International Symposium, September 6-9, 2018, London, UK; 12th European Headache Federation Congress, September 28-30, 2018, Florence, Italy

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Andrew M. Blumenfeld, MD, has served on advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, Alder, Teva, Supernus, Promius, Eaglet, and Lilly; and has received funding for speaking from AbbVie, Amgen, Pernix, Supernus, Depomed, Avanir, Promius, Teva, and Eli Lilly and Company. Atul T. Patel, MD, MHSA, has received research grant support from AbbVie, Merz, and Ipsen; and has served on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie and Merz. Ira M. Turner, MD, has served as a consultant, advisor, and/or speaker’s bureau for AbbVie, Amgen/Novartis, Biohaven, Lilly, MAP, Nautilus, Supernus, Teva, Theranica, and Zogenix; and has received research support from AbbVie, Amgen/Novartis, Biohaven, Lilly, Supernus, Teva, and Theranica. Kathleen B. Mullin, MD, has no competing interests to declare. Aubrey Manack Adams, PhD, is an employee of AbbVie and owns stock in the company. John F. Rothrock, MD, serves as a senior editorial advisor for Headache and as an associate editor for Headache Currents. He has served on advisory boards and/or has consulted for AbbVie, Lilly, Amgen, and Supernus. He also has received funding for travel and speaking from Supernus and has received honoraria from AbbVie for participating as a speaker and preceptor at AbbVie-sponsored educational programs. His parent institution has received funding from AbbVie, Amgen, and Dr. Reddy’s for clinical research he has conducted.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie).

ORCID iDs: Andrew M. Blumenfeld  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0851-4914

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0851-4914

Atul T. Patel  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2765-7953

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2765-7953

References

- 1. Schwedt TJ. Chronic migraine. BMJ. 2014;348:g1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59:1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, et al. Assessing barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache. 2016;56:821-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF. Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:22-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Head-ache Disorders, 3rd edition Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic mi-graineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31:301-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stewart WF, Wood GC, Manack A, Varon SF, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Employment and work impact of chronic migraine and episodic migraine. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:8-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manack Adams A, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al. The impact of chronic migraine: the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:563-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:86-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:428-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache. 2012;52:1456-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Botox [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Topamax [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharma-ceuticals, Inc.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate for the treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Head-ache. 2007;47:170-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diener HC, Bussone G, Van Oene JC, Lahaye M, Schwalen S, Goadsby PJ. Topiramate reduces headache days in chronic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:814-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Turkel CC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:793-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:804-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aurora SK, Winner P, Freeman MC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled analyses of the 56-week PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2011;51:1358-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mathew NT, Jaffri SF. A double-blind comparison of onabotulinumtoxina (BOTOX) and topiramate (TOPAMAX) for the prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine: a pilot study. Headache. 2009;49:1466-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weatherall MW. The diagnosis and treatment of chronic migraine. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6:115-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rothrock JF, Manack Adams A, Lipton RB, et al. FORWARD study: evaluating the comparative effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA and topiramate for headache prevention in adults with chronic migraine. Headache. 2019;59:1700-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tassorelli C, Diener HC, Dodick DW, et al. Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of preventive treatment of chronic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:815-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang M, Rendas-Baum R, Varon SF, Kosinski M. Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) across episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:357-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blumenfeld AM, Rosa K, Evans C, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the assessment of chronic migraine impacts (ACM-I) and assessment of chronic migraine symptoms (ACM-S) [abstract P15]. Headache. 2014;54(suppl 1):19. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haywood KL, Mars TS, Potter R, Patel S, Matharu M, Underwood M. Assessing the impact of headaches and the outcomes of treatment: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1374-1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tfelt-Hansen P, Pascual J, Ramadan N, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: third edition. A guide for investigators. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:6-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Silberstein S, Tfelt-Hansen P, Dodick DW, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:484-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Cycle 1 2018 funding cycle: PCORI funding announcement: pragmatic clinical studies to evaluate patient-centered outcomes 2018. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-PFA-2018-Cycle-1-Pragmatic-Studies.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- 32. Berger A, Bloudek LM, Varon SF, Oster G. Adherence with migraine prophylaxis in clinical practice. Pain Pract. 2012;12:541-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lipton RB, Varon SF, Grosberg B, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA improves quality of life and reduces impact of chronic migraine. Neurology. 2011;77:1465-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lipton RB, Rosen NL, Ailani J, DeGryse RE, Gillard PJ, Varon SF. OnabotulinumtoxinA improves quality of life and reduces impact of chronic migraine over one year of treatment: pooled results from the PREEMPT randomized clinical trial program. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:899-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blumenfeld AM, Tepper SJ, Robbins LD, et al. Effects of onabotulinumtoxinA treatment for chronic migraine on common comorbidities including depression and anxiety. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90:353-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ahmed F, Gaul C, Garcia-Monco JC, Sommer K, Martelletti P. An open-label prospective study of the real-life use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of chronic migraine: the REPOSE study. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hepp Z, Rosen NL, Gillard PG, Varon SF, Mathew N, Dodick DW. Comparative effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA versus oral migraine prophylactic medications on headache-related resource utilization in the management of chronic migraine: retrospective analysis of a US-based insurance claims database. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:862-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rothrock JF, Bloudek LM, Houle TT, Andress-Rothrock D, Varon SF. Real-world economic impact of onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with chronic migraine. Headache. 2014;54:1565-1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37:470-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]