Abstract

Objective

To gain insight into the perceptions of urology held by medical students as they enter the field, we analyzed the linguistic characteristics and gender differences in personal statements written by urology residency program applicants.

Methods

Personal statements were abstracted from residency applications to a urology residency program. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, a validated text analysis software, characterized the linguistic content of the statements. Analyzed statements were compared according to gender of the applicant using multivariate analysis, examining the association of applicant gender and statement characteristics. Multivariate analysis was also performed to determine the association of personal statement characteristics with matching into urology residency.

Results

Of 342 analyzed personal statements, no significant difference was found in statement characteristics between matched and unmatched applicants. Male and female applicants wrote with the same degree of overall analytical thinking, authenticity, and emotional tone. Clout, a measure of portrayed confidence, was low for both genders. Female applicants used more social and affective process words. Male applicants used more words indicating a sense of community and acceptance. Female applicants had more references to women within their statements.

Conclusion

Significant linguistic differences exist among personal statements written by men and women applying to urology residency. Word usage differences follow societal gender norms. Statement content demonstrates a difference between genders in perceived sense of belonging, highlighting the importance of gender concordant mentorship within the field.

The personal statement is a required portion of the standardized application for all urology residency programs within the United States. This one-page essay is used by medical students to express their career goal of entering the urology workforce, and highlight and contextualize the accomplishments listed in their application. Despite relative subjectivity and lack of evidence that personal statements correlate with future success or clinical performance, they are used in the residency application process to better determine a medical student's “fit” for a program.1 , 2 The freeform nature of the personal statement allows students to advocate for themselves in their own voice, thereby allowing insight into the personality, interests, morals, and values of each individual applicant not otherwise captured in the rest of the residency application. As USMLE Step 1 scores move to pass/fail grading and the potential implications of COVID-19 for future residency application cycles materialize, the personal statement may become more prominent in the decision making process.

Due to the individualized nature of personal statements and the difficulty in analyzing such subjective content, previous studies examining personal statements have focused on the weight of the statement in the applicant ranking process across various medical residencies with limited and varying results.3, 4, 5 With the advent of automated text analysis, more recent studies have explored the nuanced differences of both letters of recommendation and personal statements of residency applicants to various medical fields. The majority of these studies have found differences between men and women's writing that play into gender stereotypes.6, 7, 8, 9 Previously, we found that letter of recommendations written for male urology residency applicants were written in a more authentic tone, and reference themes of drive, power and work more often than letters written for female applicants.6 However, gender-based differences in personal statements of applicants to urology residency programs have not been studied.

While current urology residency match rates are equal among male and female applicants, the overall proportion of female applicants is approximately one third that of males.10 Approximately 90% of practicing urologists are male, and male patients are seen 3 times more often in the ambulatory urology setting.11 , 12 The predominantly male patient and provider environment of urology may serve as barriers to female matriculation, and these distinct differences in gender ratios throughout the specialty may influence medical students’ perception of urology, their role as they enter the field, and how their personal statements are received by reviewers. Through comprehensive linguistic analysis of personal statements of urologic residency applicants, we sought to gain insight into gender-based differences through applicant's personal statements, identifying writing characteristics unique to urology applicants and highlighting similarities and differences between male and female authors. We hypothesize that there are linguistic differences between personal statements written by male and female residency applicants that follow gender stereotypes which in turn may highlight the continued gender disparities within the field of urology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Characteristics

After receiving institutional IRB approval, residency applications submitted to the Department of Urology residency program at the University of North Carolina during the 2016-2017 application cycle were extracted from the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS). Applications were included in the study if they attended medical school in the United States. Residents who matched at the University of North Carolina urology residency during the studied application year were excluded in an effort to reduce risk of identification of the author. Descriptive data of applicants were manually extracted from their residency applications, including age, race, gender, number of gap years between medical school and residency, USMLE Step 1 score, number of research projects reported, match outcome, and medical school rank. Medical school rank was determined by examining the US News & World Report Best Medical School Research rankings reported during the 2016-2017 year.

Personal statements from included applicants were transcribed and de-identified to remove all personal information, including any personal or educational program names within the body of the personal statement. In accordance with application guidelines, each personal statement was limited to 3500 characters.

Linguistic Outcomes

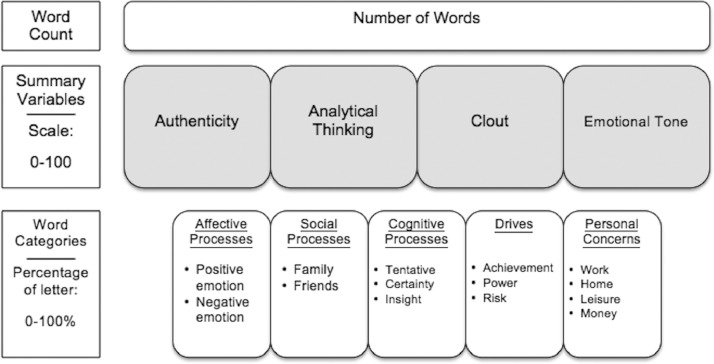

Personal statements were then analyzed using Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC), an internally and externally validated text analysis program (Pennebaker Conglomerates, Inc, Austin TX). The analysis of each statement by LIWC included an evaluation of word count, 4 summary language variables (analytical thinking, clout, authenticity and emotional tone), and the presence of 41 word categories (Fig. 1 ). Each summary language variable is a research-based composite score created using a proprietary algorithm. Their value, assigned on a 0-100 scale, quantifies text characteristics. The analytic thinking score describes how rational and formal text is. Clout refers to writing that is authoritative, confident and exhibits leadership. Authenticity refers to writing that is personal and honest. A higher emotional tone score describes positive emotions, while lower scores describe more negative writing. Word category scores determine what percentage of the analyzed text contains words referencing different psychological constructs (eg, affect, cognition, biological processes, drives, etc.) and personal concerns (eg, work, home, leisure, and activities). For example, if the word “eager” was encountered by the program in a piece of text, the score for positive emotion, affect and reward categories would increase. If the word “cried” were encountered, the score for sadness, negative emotion, and affect would increase.

Figure 1.

Linguistic inquiry and word count (LIWC) document analysis output.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report baseline applicant characteristics as well as general personal statement characteristics. Differences between male and female personal statements were analyzed using independent sample t tests. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to control for USMLE Step 1 score. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was also performed to compare personal statements of matched and unmatched applicants. Two-tailed test with P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.6.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) software.

RESULTS

Of 353 residency applications to the University of North Carolina Department of Urology residency, a total of 342 personal statements were evaluated, with 243 written by male applicants and 100 written by female applicants. Applicants of different gender were overall similar in age, race, Step 2 score, and the number of research projects submitted as part of their application, with women applicants having a slightly lower Step 1 score compared to their male counterparts (242 vs 245, P = .029, Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Characteristics of urology resident applicants by gender

| Variable | Total (N = 342) | Male (N = 242) | Female (N = 100) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 27 (2.9) | 27 (2.6) | 27 (3.6) | .868 |

| Race (N, %) | ||||

| White | 181 (52.9) | 129 (53.3) | 52 (52) | .825 |

| Asian | 86 (25.1) | 65 (26.9) | 21 (21) | .254 |

| Hispanic | 20 (5.8) | 12 (4.9) | 8 (8) | .275 |

| Black | 16 (4.7) | 9 (3.7) | 7 (7) | .190 |

| Other | 33 (9.6) | 24 (9.9) | 9 (9) | .795 |

| Top 25 program (N, %) | 52 (15.2) | 37 (15.3) | 15 (15) | .946 |

| Gap years (mean, SD) | 0 (0.8) | 0 (0.9) | 0 (0.6) | .887 |

| Research projects (mean, SD) | 8 (10.2) | 7 (10.6) | 8 (9.2) | .797 |

| USMLE Step 1 (N, SD) | 244 (14.3) | 245 (14.5) | 242 (13.4) | .029 |

| Matched (N, %) | 288 (84.2) | 205 (84.7) | 83 | .699 |

When examining summary variables scores of analytic tone, authenticity, emotional tone, and clout, personal statements written by female and male applicants received similar scores within the summary categories of analytic tone, authenticity, emotional tone, and clout. (Table 2 ). Personal statements contained high analytic tone (mean 89.18, range 0-100, with higher scores indicating predominantly formal writing) and with positive emotional tone (mean 89.28, range 0-100, with higher scores indicating positive over negative words). Authenticity was above average (mean 64.89, range 0-100, with high scores indicating more expressive writing). Notably, the score for clout was significantly lower than other summary categories (mean 36.3, range 0-100, with lower scores indicating tentative over authoritative language).

Table 2.

Characteristics of personal statements by gender of applicant controlling for USMLE Step 1 score

| All Authors | Male Authors | Female Authors | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word count, Mean (SD) | 634.5 (119.4) | 634.5 (117.9) | 663.5 (118.5) | .005 |

| Tone Variable | LIWC Scaled Score (0-100), Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytic | 89.18 (7.6) | 89.43 (7.1) | 88.60 (8.55) | .157 |

| Clout | 36.3 (9.9) | 36.18 (9.6) | 36.78 (10.8) | .509 |

| Authenticity | 64.89 (16.9) | 64.88 (17.1) | 64.92 (16.5) | .656 |

| Emotional | 89.28 (13.2) | 89.34 (13.8) | 88.94 (11.6) | .516 |

| Word Category | Percentage of Text (%), Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective process | 5.54 (1.22) | 5.51 (1.26) | 5.75 (1.12) | .045 |

| Positive emotion | 4.62 (1.13) | 4.61 (1.79) | 4.70 (1.00) | .337 |

| Negative emotion | 0.78 (0.56) | 0.74 (0.58) | 0.82 (0.51) | .025 |

| Social | 5.23 (1.76) | 4.99 (1.70) | 5.74 (1.83) | .004 |

| Cognitive process | 8.88 (1.81) | 8.84 (1.72) | 9.09 (2.02) | .369 |

| We/Us/Our | 0.17 (0.35) | 0.18 (0.37) | 0.16 (0.29) | .025 |

| Comparisons | 2.63 (0.71) | 2.66 (0.73) | 2.59 (0.66) | .674 |

| Anxiety | 0.17 (0.25) | 0.16 (0.24) | 0.23 (0.25) | .012 |

| Anger | 0.00 (0.15) | 0.00 (0.15) | 0.11 (0.15) | .273 |

| Sadness | 0.14 (0.22) | 0.13 (0.23) | 0.16 (0.21) | .219 |

| Female ref. | 0.13 (0.54) | 0.00 (0.51) | 0.19 (0.60) | .001 |

| Male ref. | 0.47 (0.83) | 0.49 (0.82) | 0.39 (0.86) | .621 |

| Insight | 3.23 (0.88) | 3.21 (0.90) | 3.26 (0.85) | .596 |

| Tentative | 1.16 (0.59) | 1.12 (0.58) | 1.24 (0.62) | .544 |

| Certainty | 1.18 (0.54) | 1.16 (0.52) | 1.23 (0.59) | .269 |

| Perceptual | 1.56 (0.67) | 1.54 (0.70) | 1.62 (0.61) | .614 |

| Achievement | 3.83 (1.28) | 3.77 (1.29) | 3.90 (1.27) | .437 |

| Power | 2.49 (0.93) | 2.50 (0.92) | 2.35 (0.95) | .405 |

| Reward | 1.66 (0.63) | 1.65 (0.66) | 1.71 (0.59) | .556 |

| Risk | 0.33 (0.29) | 0.31 (0.31) | 0.40 (0.26) | .075 |

When examining differences between male and female personal statements among subcategories, several significant differences were found. Essays written by women had a higher word count compared to men (663.5 vs. 634.5, p=0.005). When compared to male applicants, female applicants used more social words such as “family,” “friend,” “talk,” and “community” (P = .004), and affective-process-based words such as “happy” and “cried” (P = .045) in their personal statements. After adjusting for statement length and frequency differences between male and female applicants, women used on average 6.5 more social words and 3.25 more affective-process words than men. Women also had increased frequency of word usage conveying negative emotions such as “hurt,” “ugly,” “nasty,” and “sad” (P = .025) and anxiety-based words “worried,” “fearful,” “scared,” and “concerned” (P = .012, Table 2).

Conversely, male applicants used community-based words such as “we,” “us,” and “our” at a significantly higher frequency than their female counterparts (P = .025). There was no difference in frequency of first-person singular pronouns such as “I” and “me” between male and female applicants. Applicants of both genders referred to men in their personal statements at a similar rate, however female applicants made significantly more female references (female: 0.19, male: 0.00, P = .004).

Utilizing a logistic regression to control for USMLE Step 1 score, there was no statistically significant difference between LIWC characteristics between personal statements of applicants who matched and did not match into a residency program. Additional applicant variables were not included in logistic regression as they were not significantly associated with matching.

COMMENT

Gender disparity is pervasive in medicine and persistent in the field of urology. Despite a near tripling of female applicants to urology over the last few decades and recent data showing that female surgeons occupy a disproportionate volume of academic and subspecialty urology positions, there still exists a large minority of female urologists and substantial income inequality within the field.13, 14, 15 In competitive professional settings, self-promotion and gender norms may serve as a major source of gender disparity. While men are often rewarded for self-promotion, women are often penalized.16 With respect to gender norms, women are expected to use more social and relationship-oriented language that is less assertive, while men are expected to use more self-oriented and self-assured language.17 , 18 Failure to adhere to gender norms often damages career advancement, and alteration of language and behavior to maintain these expectations is common.16

Previous research comparing linguistic differences between genders in personal statements from the male-dominated fields of internal medicine and general surgery showed that while women tended to stay within the confines of social norms by writing more often about communal and social themes, both men and women wrote in equally self-promoting terms.7 , 8 This was echoed in our study demonstrating that urology applicants were found to express the same level of achievement, power and reward words, which are all associated with self-promotion. This suggests that values of male-dominated specialties encourage applicants, regardless of gender, to express more agency overall. Conversely, residents entering pediatrics, a female-dominated specialty, showed equal amounts of communal language used by male and female applicants, again suggesting that personal statement language is partially dictated by the applicant's perception of specialty-specific values of behavior and speech.9

It must also be noted that due to the gender disparity found within urology and other male-dominated medical fields, a large majority of faculty reviewers and program directors are male, which may impact how personal statements are read and received. While not previously studied, there could be also nuanced differences in perceptions that male readers form when compared to female readers as they navigate a personal statement.

Interestingly, women applying to internal medicine and general surgery self-promoted by describing examples of team work and emphasizing the emotional and relational aspects of doctoring, while men tended to itemize their accomplishments and express an individual narrative, illustrating the subtle pervasiveness of gender expectations.7, 8, 9 Similarly, our analysis shows that female medical students applying to urology used more social and affective-process words in their personal statements. By engaging in self-promotion through focusing on their relation to a team, women can appear competent while avoiding appearing immodest and contrary to expected gender norms.

Our findings also suggest that male applicants may perceive an increased sense of belonging within the field of urology. Males and females used first-person singular pronouns at the same rate. However, when compared to women, men used words such as “we,” “us,” and “our” more often in their personal statements. These words are associated with a strong sense of identity with the cohort that is being addressed. Linguistic analysis of interview transcripts and diaries found that increased use of these community-based words suggest a social connectedness and increased sense of inclusion.19 Additionally, linguistic analysis of various texts ranging from military letters to educational institution emails found a correlation between use of first person pronouns and social hierarchy, self-reported power and status. Lower ranked individuals use more first-person singular pronouns such as “I” and “me” whereas higher ranked individuals use more first-person plural pronouns such as “we” and “us.”20 This may indicate that male medical students applying into urology perceive themselves to be of a higher social rank within the medicosocial hierarchy found in healthcare and urology than female students. This may also be reflected in the increased usage of anxiety-related words by female urology applicants as compared to men. Literature on the role of gender in medical school education suggests that implicit gender bias influences the acculturation and sense of self differently between male and female students that in turn reflects on their sense of acceptance in their chosen professional community.21 , 22

Our study found that applicants to urology residency wrote their personal statements in a highly analytical and authentic style with positive emotional tone. Notably, there was a diminished clout score for all personal statements written by medical students applying into urology, implying a decreased sense of confidence and expertise. The average clout score was 36 (range 0-100), a significantly lower score than that of other summary categories of authenticity, emotional tone, and analytical processes which were higher than average scores when compared to various types of writing.19 This finding seems understandable in that a tentative tone would seem natural when a relatively inexperienced medical student is appealing to a group of more experienced physicians. Additionally, reviewers may perceive this tone as reflecting increased humility, which could be favorable to applicants. However, this finding is not consistent across medical specialties.7, 8, 9 Comparatively, clout scores were above average and approximately 15% higher among pediatric residency applicants.9

The reasons for decreased clout in the writing of urology applicants is unclear. With the exception of expressive writing (categorized as emotional writing) which has a similarly low clout score (37, range 0-100), various texts such as novels, natural speech, and newspapers show high levels of clout.19 Perhaps the perception that the urology residency match is highly competitive leads applicants to write more tentatively and emotionally. Lower clout scores could also reflect insecurity due to decreased field-specific exposure that some urology applicants may have during medical school as compared to other specialty applicants.23

Despite being the first manuscript to explore linguistic differences in personal statements among urology applicants, our manuscript must be viewed in the context of several limitations. While LIWC software has been validated for context reliability, there still remains a possibility that the tone and authorial intent could be misinterpreted if full context was considered. For example, there are words that have a different meaning in medicine as compared to lay language, which may not be accurately captured using LIWC. Secondly, while the study of linguistic analysis is growing, there remains a lack of studies evaluating personal statements for many medical specialties. Thus, we are unable with full certainty to compare and contrast the personal statements from urology residency applicants to those of other specialties. Additionally, the personal statements used were collected from the applicants to a single urology residency training program. In the 2017 application cycle, 422 applicants submitted preference lists and of the senior medical students in the United States applying, 82% percent were matched.24 While this is similar to our cohort of 342 applicants with a match rate of 84%, findings may not be generalizable to all urology residency applicants across the country.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study has important implications, with specific considerations to reduce gender disparities. As one example, increased female mentorship would provide reassurance to female urology applicants in the face of elevated male-to-female ratios throughout urology. Our findings emphasize the importance and value that female applicants place on female gender-concordant experiences, as female applicants showed a significant increase in the number of female references in their personal statements as compared to males. While there is an increasing number of female urologists in academic and fellowship trained subspecialties, women hold a disproportionately small number of department chair, vice chair, and educational directorship positions.25 , 26 There is a vital need for women to ascend to leadership positions in order to improve female mentorship within the field. Programs should strive to implement gender equality in the faculty responsible for selecting residents to limit effects of possible varied reception of personal statements written by male and female applicants. The implementation of female focused mentorship programs in medicine has shown relative increases in the number of senior faculty and leadership positions held by women.27

CONCLUSION

The subtle differences in language used by men and women in their personal statements add to growing literature supporting that societal gender-based expectations plays a pervasive role in the medical education, specialty selection, and perceived sense of belonging within a medical field. Women may experience and perceive cultural disadvantages when considering and applying to a male-dominated specialty. Maintaining awareness of the implications of gender stereotypes within medicine and urology, striving for gender equity among faculty, and implementing programs for earlier targeted mentorship of female applicants may lessen obstructions to entering the field and decrease gender disparities within urology.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure:The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Conflicts of Interest: No relevant conflicts. AS is funded by BCAN and PCORI. AS is a also on the study advisor committee and is a consultant for Photocure, Merck, Fergene, and Urogen.

References

- 1.Lee AG, Golnik KC, Oetting TA. Re-engineering the resident applicant selection process in ophthalmology: a literature review and recommendations for improvement. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White BAA, Sadoski M, Thomas S, Shabahang M. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69:340–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, Beckerly R, Segal S. Have personal statements become impersonal? An evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor CA, Weinstein L, Mayhew HE. The process of resident selection: a view from the residency director's desk. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:299–303. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00388-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naples R, French JC, Lipman JM, Prabhu AS, Aiello A, Park SK. Personal statements in general surgery: an unrecognized role in the ranking process. J Surg Educ. April. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Filippou P, Mahajan S, Deal A. The presence of gender bias in letters of recommendations written for urology residency applicants. Urology. 2019;134:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2019.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osman NY, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Walling JL, Katz JT, Alexander EK. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49:93–102. doi: 10.1111/medu.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostapenko L, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Sublette JW, Smink DS, Osman NY. Textual analysis of general surgery residency personal statements: topics and gender differences. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babal JC, Gower AD, Frohna JG, Moreno MA. Linguistic analysis of pediatric residency personal statements: gender differences. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:392. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1838-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Americal Urological Association . AUA; 2020. 2020 Urology Residency Match Statistics.https://www.auanet.org/education/auauniversity/for-residents/urology-and-specialty-matches/urology-match-results [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Urological Association . AUA; 2019. The State of the Urology Workforce and Practice in the United States. https://www.auanet.org/research/research-resources/aua-census/census-results. Accessed April 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey . CDC; 2010. Urology Factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/NAMCS Accessed April 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimsby GM, Wolter CE. The journey of women in urology: the perspective of a female urology resident. Urology. 2013;81:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nettey OS, Fuchs JS, Kielb SJ, Schaeffer EM. Gender representation in urologic subspecialties. Urology. 2018;114:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer ES, Deal AM, Pruthi NR. Gender differences in compensation, job satisfaction and other practice patterns in urology. J Urol. 2016;195:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heilman ME, Okimoto TG. Why are women penalized for success at male tasks?: the implied communality deficit. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92:81–92. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2002;288:756–764. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carnes M, Bartels CM, Kaatz A, Kolehmainen C. Why is john more likely to become department chair than jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:197–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tausczik YR, Pennebaker JW. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J Lang Soc Psychol. 2010;29:24–54. doi: 10.1177/0261927X09351676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kacewicz E, Pennebaker JW, Davis M, Jeon M, Graesser AC. Pronoun use reflects standings in social hierarchies. J Lang Soc Psychol. 2014;33:125–143. doi: 10.1177/0261927X13502654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Risberg G, Johansson EE, Hamberg K. A theoretical model for analysing gender bias in medicine. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Risberg G, Hamberg K, Johansson EE. Gender awareness among physicians–the effect of specialty and gender. A study of teachers at a Swedish medical school. BMC Med Educ. 2003;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong D, Ganesan V, Kuprasertkul I, Khouri RK, Lemack GE. Reversing the decline in urology residency applications: an analysis of medical school factors critical to maintaining student interest. Urology. 2020;136:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2019.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Urological Association . AUA; 2017. 2017 Urology Match Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu JS, Dickmeyer LJ, Nettey O, Hofer MD, Flury SC, Kielb SJ. Disparities in female urologic case distribution with new subspecialty certification and surgeon gender. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:399–403. doi: 10.1002/nau.22942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han J, Stillings S, Hamann H, Terry R, Moy L. Gender and Subspecialty of Urology Faculty in Department-based Leadership Roles. Urology. 2017;110:36–39. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farkas AH, Bonifacino E, Turner R, Tilstra SA, Corbelli JA. Mentorship of women in academic medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1322–1329. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04955-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]