Highlights

-

•

The first attempt to develop reliable and valid OI and ODI measures to assess the employees’ psychological attachment and separation in the foodservice industry using the mixed method.

-

•

The results from EFA and CFA showed that a single dimension is appropriate to capture the scope of both employee's OI and ODI in the foodservice industry and are consistent with major social identity studies.

Keywords: Organizational disidentification, Food service, Scale development, Organizational identification

Abstract

This study is to test whether social identity theory can be applied to employees in the foodservice industry. Modified measures of OI and ODI using a mixed-method developed and tested and presented empirical evidence for the reliability and validity of the scales.

To specify the domain of construct, the existing measures of social identification varied across studies were reviewed. A preliminary list of OI and ODI measurement scales were generated based on previous measures and data from personal interviews with foodservice workers. An expert group reviewed items and removed irrelevant and redundant ones. Also, two online surveys were conducted to validate the measurements and identify the underlying structures of the constructs. The findings of this study suggest that the final measures of OI and ODI using the categorical dimension approach are one-dimensional, reliable, and valid.

1. Introduction

According to the 2019 Restaurant Industry Factbook of the National Restaurant Association (Restaurant industry factbook, 2019), the restaurant industry sales for 2019 are expected to total $880 billion, which represents 4% of USA’s gross domestic product and projected to employ 15.3 million people in 2019, which is approximately 10% of working Americans.

The most important asset in the foodservice industry is people. Acquiring and retaining good employees is the key to success. Service quality highly relies on who the providers are, and it limits quality control. However, one of the serious issues that the foodservice industry faces is high turnover. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the voluntary quit ratio of accommodations and foodservice industries in 2017 was 52.1%, which is considerably higher than the industry average of 26.0% The employee turnover rate of quick-service restaurants was approximately 150% (MIT Technology Review, 2018). Having a high turnover rate directly hurts the sustainability of businesses and customer experiences.

Given the turnover’s effect on businesses, scholars and practitioners have strived to identify the reasons of voluntary employee turnovers, such as reward and compensation (e.g., Milkovich and Newman, 1999), age and generation (e.g., Brown et al., 2015), personality characteristics (e.g., Aziz et al., 2007), and job satisfaction (e.g., Nadiri and Tanova, 2010). The foodservice industry has unique characteristics that differentiate it from other industries, such as tips, minimum youth wages, and a high percentage of part-time workers. Foodservice organizations in 42 states in the USA can pay $2.13 per hour for tipped employees. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ report (2017), 11.6% of employees age 16 and older in food preparation and serving-related occupations earn below minimum wage that is considerably higher than the industry average of 1.6%. Many positions in the foodservice industry are entry-level, part-time, and temporary jobs (Long, 2018). Approximately 86% of employees in quick-service restaurants have part-time and non-managerial positions, and they are ranked among the lowest-paying jobs in the USA economy. Moreover, hospitality workers often face the problem of work-life conflict due to the nature of the industry. Many foodservice workers must work late nights, early mornings, weekends, or holidays. However, the problems facing foodservice organizations are not easily solved without changing the fundamental operating systems. For example, an organization may find difficulty raising employees’ wages without changing the menu prices, and changing the working hours without changing the operating hours may be challenging. Therefore, hospitality scholars have focused on psychological factors to mitigate the negative working characteristics of the service industry.

Social identity theory (SIT) has frequently been used in predicting work-related intention and attitudes (Riketta et al., 2006). Organizational identification (OI), a form of social identification, can be regarded as a psychological attachment to an organization and generates positive behavior toward the organization (Edwards, 2005). Individuals who perceive themselves as part of social groups internalize these groups as part of their self-concept, and these processes can promote group behaviors (Turner, 1982).

Scholars have found that OI is positively related to compliance, commitment (O’Reilly and Chatman, 1986), and perceived organizational citizenship behaviors (Chiaburu and Byrne, 2009). The findings of a meta-analysis by Lee et al. (2015) showed that OI is significantly related to employees’ organizational attitudes, such as job involvement, job satisfaction, affective organizational commitment, and in- and out-role organizational behaviors. Previous research has also shown that OI decreases employees’ turnover intentions (van Knippenberg, 2000; Van Dick et al., 2004).

However, OI alone cannot accurately explain how and why employees cognitively or emotionally separate from the organization. Therefore, organizational researchers have started to examine topics beyond basic OI (DiSanza and Bullis, 1999; Pratt, 2000; Mael and Ashforth, 2001). Organizational disidentification (ODI) refers to a sense of separateness with the organization (Elsbach and Bhattacharya, 2001). Employees tend to psychologically distance themselves with the organization, which is stigmatizing or violating personally relevant moral standards (Becker and Tausch, 2014) to maintain positive distinctiveness and avoid negative images attributed to the organization (Elsbach and Bhattacharya, 2001). Then, employees construct their authentic identities (“who I really am”). ODI is different from a low level of identification because it occurs when employees identify themselves in opposition to the organization (Pratt, 2000). Kreiner and Ashforth (2004) proposed that OI and ODI are individually distinct psychological states that have their respective salient antecedents (Kreiner and Ashforth, 2004).

Identification is an essential psychological phenomenon in organizational settings. Despite the empirical support that has accumulated for the conceptualization of the SIT variable and multiple scales used to measure its dimensions, the conceptualization and operationalization processes have been inconsistent. The literature review on this topic reveals a lack of a homogeneous conceptualization of social identity measures from the organizational behavior perspective. Furthermore, the appropriateness of SIT measures in the hospitality industry, particularly in the foodservice sector, has not been examined. Two modified OI and ODI scales were developed to assess foodservice workers’ social identity with the organization. Moreover, the paucity of research in ODI leaves theories underdeveloped (Becker and Tausch, 2014). Besides, scholars have argued whether OI and ODI are unique constructs. To control the working environment more effectively, it is important to identify the dimensionality of the factors.

The present study outlines how OI and ODI have been measured in previous studies. It also attempts to contribute further insights into the nature, dimensionality, and measurement of OI and ODI. This study aims to (1)modify and confirm existing social identity scales that measure employees’ identification and disidentification with the organization and which have desirable reliability and validity and (2) identify underlying dimensions of OI and ODI in the foodservice industry.

The present study provides several contributions. The foodservice industry is characterized differently from other industries, including other hospitality industries. Thus, social identity measures for the foodservice industry may include distinctive features. This study develops reliable and valid scales of OI and ODI not only by modifying or confirming existing measures but also adding new items using a mixed methodology. Furthermore, the measures can be utilized to identify the antecedents, consequences, and potential moderators of OI and ODI that should be clarified to fill in any gap in previous research.

This study aims to develop reliable and valid measures of OI and ODI that can be used for food service workers. The findings of this study suggest that the final measures of OI and ODI using the categorical dimension approach are one-dimensional, reliable, and valid.

2. Literature review

2.1. Organizational identification (OI)

SIT has long been recognized as an important theoretical framework to predict an individual’s behaviors (Van Dick et al., 2004). OI defined as “perceived oneness and belongingness to an organization” (Mael and Ashforth, 1992, p. 103). According to SIT’s assumptions, OI is formed, employees view themselves as members of the organization (Boroş, 2008). Employees with OI tend to feel proud to be a part of the organization and respect its values and accomplishments. Also, they are more likely to be motivated and to be linked with positive organizational attitudes or behaviors (Kelman, 1958) and tend to act in a way that complies with the norms and stereotypes of the organization. (Whetten and Godfrey, 1998, p. 185). Furthermore, the employees’ self-perception tends to be depersonalized and they perceive the success or failure of the organization as one’s success or failure. Then, they may strive to maintain or enhance their positive and distinctive self-concept (Hogg and Terry, 2000) through the success or prestige of the organization. Thus, highly identified employees are more likely to exert effort for organizational success to enhance their self-esteem (Dutton et al., 1994; van Dick et al., 2004).

Because of the benefits of OI may bring to organizations, numerous antecedents of OI have been explored in existing research. Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) noted that an organization's identity attractiveness was linked to self-consistency motives ("how similar it is to employee's own identity"), self-differentiation motives ("how distinctive it is with other social groups"), and the satisfaction of self-enhancement motives ("how prestige it is").

2.2. Organizational disidentification (ODI)

Compared with OI, organizational disidentification (ODI), as an extended form of social identification (Kreiner and Ashforth, 2004), has received relatively less attention. Elsbach and Bhattacharya (2001) defined ODI as “self-perception based on a cognitive separation between one's identity and the organization's identity and a negative relational categorization of oneself and the organization” (p. 393). When employees perceive that they define themselves as not having the same values or principles, ODI occurs. To maintain positive distinctiveness, they dissociate themselves from the incompatible values and undesirable stereotypes of the organization (Elsbach and Bhattacharya, 2001). Lai, Chan, and Lam (2013) found a positive relationship among ODI, perceived moral dirtiness and intention to leave in a sample of casino employees. When the employees perceive their work to be morally dirty, then their levels of occupational and organizational disidentification were higher which led to higher turnover intention.

Previous studies found that ODI was positively associated with intra-role conflict, negative affect, and cynicism (Kreiner, 2002), person-organization fit and abusive supervision (Chang et al., 2013) while negatively with organizational reputation, psychological contract fulfillment, negative affect, and individualism (Kreiner, 2002). Disidentification may take multiple forms, including cynicism, humor, skepticism, and irony (Costas and Fleming, 2009). Also, OIDs can result in negative consequences such as increased turnover intention (Lai et al., 2013) or reduced efforts on long-term tasks (Dutton et al., 1994). ODI also may lead to undesirable behaviors such as opposing the organization, criticizing the organization publicly (Elsbach and Bhattacharya, 2001). Furthermore, some employees may consider their organizations as “rivals” or even “enemies” (Lawrence and Kaufmann, 2011) and perform supportive behaviors for an opposing organization (Elsbach, and Bhattacharya, 2001). Also, they tend to view the organization in a negative or pessimistic way and embrace potential negative experiences and attitudes (Kanter and Mirvis, 1989; Kreiner and Ashforth, 2004). Then ODI can be used as a defensive mechanism by non-prototypical low identifiers who searching for a more desirable outgroup (Ellemers et al., 1999) which may lead to volunteer turnover.

2.3. Review of existing measures of identification

Much literature has focused on identification with the social group (e.g., Mael and Ashforth, 1992; Kreiner and Ashforth, 2004; Ikegami and Ishida, 2007). Many scholars believe that OI overlaps with organizational constructs such as involvement, satisfaction, and commitment (Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Mael and Tetrick, 1992; Pratt, 1998). However, after Mael and Ashforth (1992), organizational researchers empirically tested and supported that OI is a unique conceptual construct (e.g., Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Pratt, 1998; van Knippenberg and van Schie, 2000).

Researchers also have debated whether OI is unidimensional or multidimensional. Mael and Ashforth (1992) developed a unidimensional OI scale to measure alumni’s identification with their religious school. The measures were generated based on Ashforth and Mael’s (1989) definition of OI: “perception of oneness with or belongingness to some human aggregate” (p. 21). The scale consists of six items and is one of the most frequently used OI measures (Riketta, 2005). In addition to Mael and Ashforth’s (1992) scale, various unidimensional group identification measures with various social groups are developed. Examples include OI (Cheney, 1982), sports fan identification (Wann and Branscombe, 1993), national identification (Verkuyten, Yildiz, 2007), cultural identification (Zou, Morris & Benet-Martínez, 2008), and brand identification (Wolter, Brach, Cronin Jr, & Bonn, 2016). In Voelkl’s (1997) study, the overall goodness of fit for the two-factor model that consisted of separate measures of belonging and valuing is not significantly better than that of the unidimensional model. Also, Shamir and Kark (2004) presented a simple graphical scale for the measurement of identification with the organization. The circles in the graphical measure overlap differently. The degree to which the two circles overlapped indicates the extent to which an employee identified with the organization. However, the graphic scale was not superior to the verbal scales of OI and requires further empirical support of its reliability and validity.

In contrast, several researchers were interested in identifying and examining the components of group identification. Tajfel (1981) proposed that group identification consists of three dimensions. 1) The cognitive factor recognizes group membership that can help individuals to organize in the social group. 2) The evaluative factor provides meaning by comparing ingroups with outgroups. 3) The affective factor is emotionally involved with the particular social group (Van Dick et al., 2004). Miller et al. (2000) also identified three dimensions from Cheney’s (1982) 25-item OI questionnaire (OIQ). They found that only 12 items contribute to the OI scale, and they are composed of three factors: membership (3 items), loyalty (6 items), and similarity (3 items). Cameron (2004) also suggested a three-factor model of social identity that consists of 1) centrality, “the frequency with which the group comes to mind” and “the subjective importance of the group to self-definition” (p. 243); 2) ingroup affect, “specific emotions that arise from group membership” (p.243), and 3) ingroup ties, “the extent to which group members feel ‘stuck to,’ or part of, particular social groups” (Bollen and Hoyle, 1990, p. 482). In their study, the three-factor model has a superior fit to one- or two-factor models.

2.4. Review of existing measures of disidentification

Disidentification has been studied in different areas of research, such as national disidentification (e.g., Verkuyten, and Yildiz, 2007), customer disidentification (e.g., Josiassen, 2011; Wolter et al., 2016), ODI (e.g., Elsbach and Bhattacharya, 2001), and academic disidentification (e.g., Osborne, 1997). Although several researchers addressed disidentification, little empirical evidence exists regarding its structure, measurement, antecedents, and consequences.

Kreiner and Ashforth (2004) developed measures of the four dimensions of the expanded model: identification, disidentification, ambivalent identification, and neutral identification; they tested the operationalization of the four dimensions. The four factors are correlated but support the discriminability of the disidentification construct.

Most organization scholars suggested and used unidimensional scales to measure disidentification. Elsbach and Bhattacharya (2001) conducted an exploratory study. They developed a three-item scale and tested a framework of ODI with focus groups consisting of university students, faculty, and staff. The measures were generated based on the following definitions: “cognitive separation between one’s identity and organization’s identity” and “one’s negative relational categorization of oneself and the organization” (p. 393). Several other researchers also developed unidimensional scales to measure disidentification (e.g., Silver, 2001; Ikegami, Ishida, 2007; Verkuyten, and Yildiz, 2007; Zou et al., 2008).

However, Becker and Tausch (2014) argued that disidentification has more than one dimension and introduced a multi-dimension model of group disidentification consisting of 1) detachment, “a negative motivational state that ranges from feelings of rather passive alienation and estrangement to an active separation from one’s ingroup;” 2) dissatisfaction, a feeling of “unhappy about belonging to the group and regret their group membership;” and 3) dissimilarity, “the degree to which individuals perceive themselves as different from the ingroup prototype” (p. 295–296). They found that the three-factor model fits the data better than the one-factor model with two samples with different cultural and linguistic situations. The study also found that identification and disidentification can be distinct factors. Group disidentification measures predict negative behavioral intentions better than identification measures, whereas the identification measures predict positive behavioral intentions better than the disidentification scales. Table 1 presents a summary of the identification and disidentification measures proposed in previous research.

Table 1.

Review of existing measures of identification or disidentification.

| Authors | Classification | Dimensions | No. of Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | |||

| Cheney (1982) | Organizational identification | Unidimensional | 25 |

| Hinkle, Taylor, Fox‐Cardamone, & Crook (1989) | Group identification | Unidimensional | 8 |

| Mael & Ashforth (1993) | Organizational identification | Unidimensional | 6 |

| Wann and Branscombe (1993) | Team Identification | Unidimensional | 7 |

| Miller, Allen, Casey, & Johnson, (2000) | Organizational identification | Multidimensional Membership (3) Loyalty (5) Similarity (4) |

12 |

| Kreiner, Ashforth (2004) | Organizational identification | Unidimensional | 6 |

| Cameron (2004) | Organizational identification | Multidimensional Ingroup ties (4) Centrality (4) Ingroup affect (5) |

13 |

| Kreiner and Ashforth (2004) | Organizational identification | Unidimensional | 6 |

| Verkuyten and Yildiz (2007) | National identification | Unidimensional | 6 |

| Ikegami and Ishida (2007) | Organizational identification | Unidimensional | 9 |

| Zou, Morris & Benet-Martínez (2008) | Cultural identification | Unidimensional | 7 |

| Wolter, Brach, Cronin Jr, & Bonn (2016) | Brand identification | Unidimensional | 4 |

| Lee et al. (2015) | Organizational identification | Unidimensional | 5 |

| Disidentification | |||

| Elsbach and Bhattacharya (2001) | Organizational disidentification | Unidimensional | 3 |

| Silver (2001) | Group disidentification | Unidimensional | 9 |

| Kreiner& Ashforth (2004) | Organizational disidentification | Unidimensional | 6 |

| Ikegami and Ishida (2007) | Organizational disidentification | Unidimensional | 11 |

| Becker, & Tausch. (2014) | Group disidentification | Multidimensional Detachment (3) Dissatisfaction (4) Dissimilarity (4) |

11 |

| Verkuyten and Yildiz (2007) | National identification | Unidimensional | 6 |

| Zou, Morris & Benet-Martínez (2008) | Cultural identification | Unidimensional | 7 |

| Matschke & Sassenberg (2010) | Organizational identification | Multidimensional Exit (3) Recategorization (3) Bad feeling (6) |

12 |

| Wolter, Brach, Cronin Jr & Bonn (2016) | Customer-brand disidentification | Unidimensional | 4 |

Although the identification studies have expanded in scope, whether existing measures are suitable to measure employees’ identification and disidentification in the foodservice industry has not been examined. The restaurant industry has a higher employee turnover rate than other industries do (The Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018), and average employee tenure is just one month and 26 days (7shifts.com, 2018), possibly leading to a different type of psychological attachment or detachment with the organization. Thus, the present study developed the measures of OI and ODI that can apply to restaurant employees.

3. Method

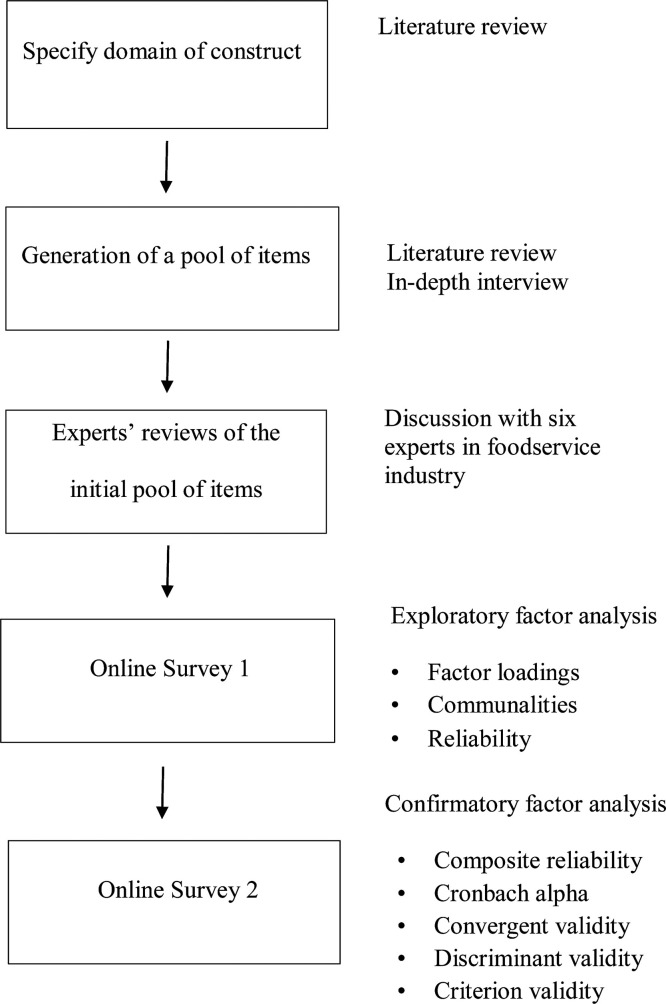

The scale development procedures were followed by guidelines of Churchill’s (1979), Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988), and Gerbing and Anderson (1988). Fig. 1 presents the scale development process.

Fig. 1.

Procedure to Develop OI and ODI scales.

3.1. Specify domain of construct

According to Churchill’s paradigm (1979), the first step of this study was specifying the domain of the construct and a literature review. Scholars are increasingly focusing on intangible resources and relationships in organizations (Lusch and Harvey, 1994), but assessing employees’ OI and ODI in the foodservice industry was rarely conducted. First, relevant items from reviewing the existing literature were identified. Identification and disidentification have been studied in different areas of research such as nationalism, customer marketing, academic area, and ranging in length from three items to 25 items and unidimensional to multidimensional (see Table 1). 11 OI and nine ODI scales identified in the literature measuring the constructs were analyzed to generate potential items for the new scale.

3.2. Generate samples of items

The next step is to create a large pool of items to capture the domain as specified. (Churchill, 1979). The measure of social identification varied across the studies (see Table 1). Existing measures included cognitive (e.g., centrality, membership), evaluative (e.g., similarity), and affective factors (e.g., ingroup bond, ingroup tie) (Tajfel, 1981; Miller et al., 2000; Cameron, 2004).

A preliminary list of OI and ODI measurement scales were generated based on previous measures. According to Shimp and Sharma’s (1987) key elimination criteria, redundant, ambiguous items were removed and a total of 44 OI items and 37 ODI items from literature reviews were remained.

3.2.1. Personal interview

The procedure for the personal interview was derived from various sources (i.e., Valenzuela and Shrivastava, 2002; Longhurst, 2003; Bourne and Jenkins, 2005). Sixteen participants were interviewed by a member of the research team using a semi-structured interview process within an individual interview setting. The purpose of this in-depth interview was to uncover specific characteristics of employees’ psychological attachment or detachment with their organizations. The interviewees were composed of current foodservice workers and asked to describe their perceptions in an open format. The sample questions and answers for the interviews are summarized in Table 2 . Follow up questions were asked depends on interviewees’ answers. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. The average length of the individual interviews was 30 min. To protect participants’ confidentiality, participants were coded with numbers (P1 to P16). The average industry tenure was 4.5 years (n = 16), and 9 interviewees (57%) were male. Most of the participants worked in more than one food service facility and experienced multiple positions. All participants have working experiences not only in restaurants but also in other industries. The information of the participants is presented in Table 3 . Quotes were coded and categorized. Redundant quotes were removed from the pool. A list of 11 OI items and 10 ODI items were generated by these interviews.

Table 2.

Sample Interview questions and answers.

| Organizational identification |

| Is there any brand or restaurant you especially attach to and still talk to others about? Why? P1: “My current work, a manager is his best friend, feel the casual family working environment. no hierarchical relationship” “shut down on a busy day and took employees to a festival.” P3: “Sports bar, more comfortable, easier to talk to, not demanding, more relaxed environment.” |

| Do you feel attached to current workplace? If yes, why? P2: “I like everything about that. I loved everything. Bosses, coworkers, food…. It was coordinated, systematic… This job means a lot to me” P15: “I was bonded with employees like family. We have so much in common. We used to do a lot of stuff together inside and outside of work. We enjoyed working together.” |

| How do you like the current work and the position? P15: “I have a passion for it. I love to cook.” |

| Is there anything you do for a company other than your work duties because you like it? P2: “Job refer, I referred 3 friends”. P1: “I go to the workplace on my day-offs and hang out, make sure everything is organized, cook food for other employees” |

| How do you know that you like the organization? P13: I love it. I never go to work hating my job. P16: “Good comment, we feel good. If they are bad, we need to figure out who was the one took care of the table” |

| How do you spot out the person who really likes the organization at your work? P4: “they are putting efforts and try hard.” P13: “They always think “What can I do, what can I do?” |

| Organizational disidentification |

| Do you feel attached to your current workplace? If no, why? P3: “hate it absolutely hate it. The management is terrible, the chef is terrible, I just all around terrible. I am only there, I about to graduate in December” P4: “All of us don’t want to be. Especially hospitality job, you have to have mentality we have to put you in their shoes.” |

| How do you know that you dislike the organization? P11: “I would not really think twice going somewhere else if I have a better opportunity.” |

| While you were working in this restaurant (brand), was there any moment you thought “I do not belong here”? Why? P2. “I was only American waiter, youngest. However, I never feel out of place anywhere. It is my personality.” P7: “I don’t really talk with coworkers because they speak Spanish. We have different cultures. I only meet them at work.” P4: “The first time I started to work in XXX, I didn’t know anything about XXX. I didn’t know what to do. Everyone else is so much better than me. I didn’t feel like I am belonging there. |

| What made you leave the (previous) organization? P13: “it was so hard because I felt lost.” |

| How do you spot out the person who dislike the organization at your work? P3. “Standing looking dead, just want to collect paychecks, they will leave, as soon as find another job.” P10: “people do for the credits, they are barely doing the minimum.” |

Table 3.

Industry tenure, position, gender of participants.

| Label | Organization | Industry Tenure (year) | Position | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | Pizza restaurant, bar, Premium casual restaurant | 6.5 | server, assistant manager, bartender | Male |

| P2 | fast food, cruise ship, casual dining | 8 | server, head server, host, expo | Male |

| P3 | Country club, sports bar, fine dining | 5 | server, bartender | Female |

| P4 | Casual dining | 0.5 | dishwasher, server | Male |

| P4 | fast food | 4 | kitchen supervisor | Male |

| P6 | Casual dining, hospital | 12 | host, busser, expo, bartender, server, prep cook | Male |

| P7 | Chinese casual dining, Hotel restaurant1.5 years | 1.5 | server, expo | Female |

| P8 | Bar | 1 | server | Female |

| P9 | Milk tea, banquet, fine dining | 3 .5 | sever, expo, runner, purchasing | Male |

| P10 | Casual dining | 0.6 | catering manager | Female |

| P11 | Fast food | 0.75 | crew | Male |

| P12 | Ice cream vendor, casual dining | 3.5 | vendor, server, cashier | Male |

| P13 | Japanese casual dining | 0.9 | server | Female |

| P14 | Casual dining | 2.5 | hostess, server | Female |

| P15 | Catering | 5 | independent cater, cook | Female |

| P16 | Vietnamese casual dining | 4.5 | server | Male |

4. Expert input

Six experts consisting of a faculty member, restaurant employees, and pH.D. students were selected and reviewed the items generated by the literature search and personal interviews. All reviewers had extensive experience in the foodservice industry. The review started with open-ended questions regarding their working experiences in the foodservice industry. Then Lawshe’s (1975) technique was used to review the items. Reviewers marked each item as either ‘keep’, ‘useful, but not essential’, or ‘remove. A total of 42 OI items and 38 ODI items from the literature review and 21 items from personal interviews were reviewed. Redundant items and ambiguous items were removed or modified. 14 OI and 15 ODI items, agreed by all six experts, were included in the questionnaire. The list of 29 items presents in Table 4 .

Table 4.

An initial list of selected items.

| Label | Item | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| OI1 | XXX's successes are my successes. a | 3.60 | 1.23 |

| OI2 | Being a part of XXX is important to me. b | 3.67 | 1.18 |

| OI3 | I am interested in XXX's growth | 3.81 | 1.16 |

| OI4 | When I see positive (online) guest comments, I am proud of being part of XXX. | 3.91 | 1.09 |

| OI5 | I feel a strong attachment to XXX. < removed> c | 3.54 | 1.25 |

| OI6 | I feel a strong sense of belonging to XXX. c | 3.62 | 1.22 |

| OI7 | I find that my values and the values of XXX are very similar. d | 3.63 | 1.17 |

| OI8 | I have a lot in common with others in XXX. e | 3.72 | 1.12 |

| OI9 | I really want to contribute to the success of XXX. < removed> | 3.84 | 1.10 |

| OI10 | I see myself as an important part of XXX. f | 3.66 | 1.20 |

| OI11 | I would describe XXX as a large family in which most members feel a sense of belonging. e | 3.67 | 1.19 |

| OI12 | [Name of the restaurant (brand)] means a lot to me. | 3.67 | 1.18 |

| OI13 | When someone praises XXX, it feels like a personal compliment. < removed> g | 3.69 | 1.17 |

| OI14 | I feel embarrassed when someone criticizes XXX. a | 3.39 | 1.24 |

| ODI1 | I do not consider XXXX to be important. f | 2.29 | 1.28 |

| ODI2 | I'm completely different from other employees of XXX. h | 2.64 | 1.26 |

| ODI3 | I don't care about XXX's goals. <removed> | 2.19 | 1.26 |

| ODI4 | I am not aligned well with the organizational culture of XXX. | 2.20 | 1.21 |

| ODI5 | I feel like I do not fit at XXX. < removed> f | 2.19 | 1.23 |

| ODI6 | I feel uncomfortable being perceived as an employee of XXX. i | 2.20 | 1.30 |

| ODI7 | It is hard to find something common between myself and others in XXX. <removed> | 2.24 | 1.20 |

| ODI8 | I felt so lost sometimes in XXX. <removed> | 2.18 | 1.26 |

| ODI9 | I have the tendency to distance myself from XXX. c | 2.24 | 1.28 |

| ODI10 | I have tried to keep XXX I work for a secret from people I meet. < removed> j | 2.07 | 1.24 |

| ODI11 | It is good if people say something bad about XXX. k | 1.88 | 1.13 |

| ODI12 | The organization's success or failure is not my interest. | 2.29 | 1.30 |

| ODI13 | Overall, being an employee of XXX has very little to do with how I feel about myself. l | 2.69 | 1.36 |

| ODI14 | I regret that I belong to XXX. h | 2.03 | 1.18 |

| ODI15 | My personality does not match well with the organizational culture of XXX. <removed> | 2.27 | 1.28 |

* a - Mael and Ashforth, 1992, b - Lee et al., 2015, c - Verkuyten and Yildiz, 2007, d - Porter & Smith, 1970, e - Cheney, 1982, f - Hinkle et al., 1989, g - Ikegami and Ishida, 2007, h - Becker and Tausch, 2014, i - Zou et al., 2008, j - Kreiner and Ashforth, 2004, k - Josiassen, 2011, l - Cameron, 2004, Italic – new.

4.1. Data collection 1

To identify clusters of variables from the expert meeting, two online surveys were conducted. The first online survey was distributed to 600 restaurant employees in the USA through MTurk during May 2019. We conducted a pre-survey screen to ascertain that they reside within the US, at least 18 years of age, are fluent in English, and are current restaurant employees. To increase the validity, one attention question that asked to choose “strongly disagree” was included. 62 were screened out because they provided wrong answers. Also, the name and concept of the foodservice facility where the participant is currently working were asked. Thirteen cases that two answers were not matched were deleted. A total of 475 responses remained after deleting the responses that answered wrong on attention questions. Then 20 extreme outliers (Mahalanobis’ D (29) > 116.916, p < .001) were removed. Finally, a total of 455 remaining questionnaires were used for the data analysis. The responses range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). 39.1% of the participants worked in fast or fast-casual restaurants, 29.4% of participants worked in managerial positions, and the average of the organizational industry term was 2.8 and 5.9, respectively and 39.6% of participants were part-time.

EFA was conducted using the principal axis factoring method and Promax rotation approach that had the advantage of being fast and useful for large datasets (Abdi, 2003) to identify the underlying dimensions and items within each derived dimension for the final factor solution. An EFA with all OI and ODI (29 items) measures was conducted and produced two factors. From OI1 to OI14 loaded to one factor and from ODI1 to ODI14 loaded to another factor. Descriptive statistics, factor loadings correlation matrix of the EFA were examined and nine redundant items that correlated with 0.8 or higher were removed.

Another EFA was performed with the remaining 20 items. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy/ Bartlett's Test of Sphericity was used to test the suitability of the respondent data for factor analysis. Items and their respective factor loadings are present in Table 5 . The Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis of the items. KMO measure was 0.96 (‘marvelous’ according to Hutcheson and Sofroniou, 1999) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < .05). All KMO values for individual items were greater than 0.93, which is well above the acceptable limit of .5 (Field, 2013). The correlation coefficient between the two factors was -0.64. Two factors had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 explained 66.9% of the variance. The first factor (11 OI items) explained 53.3% of the variance and the second factor (9 ODI items) explained 10.6% of the variance. The Cronbach’s α of the OI factor was 0.95 and that of the ODI factor was 0.93 (Nunnally, 1978). Also Table 6 presents the intercorrelations of the items.

Table 5.

Exploratory Factor Analysis Results (n = 455).

| Communality | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OI1 | 0.66 | 0.86 | |

| OI2 | 0.74 | 0.84 | |

| OI3 | 0.73 | 0.81 | |

| OI4 | 0.59 | 0.62 | |

| OI6 | 0.78 | 0.90 | |

| OI7 | 0.69 | 0.83 | |

| OI8 | 0.54 | 0.69 | |

| OI10 | 0.70 | 0.80 | |

| OI11 | 0.72 | 0.85 | |

| OI12 | 0.81 | 0.94 | |

| OI14 | 0.32 | 0.63 | |

| ODI1 | 0.68 | 0.71 | |

| ODI2 | 0.29 | 0.55 | |

| ODI4 | 0.76 | 0.77 | |

| ODI6 | 0.67 | 0.87 | |

| ODI9 | 0.75 | 0.81 | |

| ODI11 | 0.57 | 0.89 | |

| ODI12 | 0.69 | 0.74 | |

| ODI13 | 0.42 | 0.60 | |

| ODI14 | 0.71 | 0.84 |

Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. Rotation Method: Promax with Kaiser Normalization.

Table 6.

Inter-Item Correlation Matrix.

| OI1 | OI2 | OI3 | OI4 | OI6 | OI7 | OI8 | OI10 | OI11 | OI12 | OI14 | ODI1 | ODI2 | ODI4 | ODI6 | ODI9 | ODI11 | ODI12 | ODI13 | ODI14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OI1 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| OI2 | 0.73 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| OI3 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| OI4 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| OI6 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| OI7 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| OI8 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.62 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| OI10 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.58 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| OI11 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| OI12 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| OI14 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| ODI1 | −0.51 | −0.61 | −0.56 | −0.51 | −0.54 | −0.54 | −0.43 | −0.52 | −0.50 | −0.53 | −0.28 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ODI2 | −0.30 | −0.28 | −0.27 | −0.28 | −0.30 | −0.28 | −0.44 | −0.28 | −0.30 | −0.27 | −0.02 | 0.47 | 1.00 | |||||||

| ODI4 | −0.49 | −0.56 | −0.55 | −0.55 | −0.55 | −0.55 | −0.49 | −0.55 | −0.54 | −0.55 | −0.28 | 0.73 | 0.52 | 1.00 | ||||||

| ODI6 | −0.33 | −0.42 | −0.45 | −0.40 | −0.41 | −0.41 | −0.42 | −0.41 | −0.44 | −0.40 | −0.19 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 0.69 | 1.00 | |||||

| ODI9 | −0.43 | −0.48 | −0.51 | −0.54 | −0.48 | −0.44 | −0.47 | −0.51 | −0.55 | −0.48 | −0.31 | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 1.00 | ||||

| ODI11 | −0.21 | −0.28 | −0.36 | −0.44 | −0.25 | −0.24 | −0.21 | −0.33 | −0.24 | −0.24 | −0.15 | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 1.00 | |||

| ODI12 | −0.45 | −0.54 | −0.55 | −0.51 | −0.50 | −0.48 | −0.44 | −0.56 | −0.48 | −0.55 | −0.37 | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 1.00 | ||

| ODI13 | −0.36 | −0.38 | −0.42 | −0.39 | −0.41 | −0.40 | −0.34 | −0.43 | −0.37 | −0.39 | −0.29 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 1.00 | |

| ODI14 | −0.38 | −0.46 | −0.48 | −0.56 | −0.46 | −0.43 | −0.40 | −0.45 | −0.46 | −0.46 | −0.24 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 1.00 |

4.2. Data collection 2

Another online survey using MTurk was conducted to assess validity and reliability (Churchill, 1979). The survey was distributed electronically to 250 restaurant employees in the USA during June 2019. Ten responses that a restaurant name and the restaurant concept did not match were removed from the sample. Also, 12 responses with an incorrect response for the attention check question were removed from the sample. Tests for multivariate outliers found 10 significant cases (Mahalanobis’ D (29) > 116.89, p < .001), and they were removed from further analyses. A total of 218 responses remained. 39.1% of the participants worked in fast or fast-casual restaurants, 38.3 percent of participants were part-time, and the average of the organizational tenure and industry tenure was 2.8 and 5.7, respectively.

4.3. Assess reliability and validity

Confirmatory factor analysis was used to verify empirically whether the number of dimensions was conceptualized correctly (Churchill, 1979) and to directly tests the unidimensionality of constructs (Gerbing and Anderson, 1988). When dimensionality was confirmed, the reliability of each construct was assessed. The average variance extracted was calculated to verify the convergent and discriminant validity (Hair et al., 1998).

A CFA was performed using the maximum likelihood method to establish unidimensionality and composite reliability and construct validity (Gerbing and Anderson, 1988; Anderson and Gerbing, 1988) via Mplus 7.4. First, 11 OI items loaded to one latent variable and 9 ODI items loaded to another latent variable in the hypothesized model (M0). The first factor represented general aspects of organizational identification, while a second factor represented general aspects of organizational disidentification. The values of goodness-of-fit indices were acceptable. (df = 188, χ2 = 393.38, CFI = 0.95 TLI = 0.95 RMSEA = 0.07 SRMR = 0.05). The hypothesized measurement factor loadings were all statistically significant (p < 0.05), and the lowest factor loading of OI items was 0.58 (OI14), and the lowest factor loading of ODI was 0.58 (ODI2). Items and their respective factor loadings are present in Table 7 . In the present case, the hypothesized two-factor CFA model (M0) was compared to the fit of a one-factor model that assumes that all 20 items measuring OI and ODI all loaded to one latent factor (M1). To compare these models, the likelihood ratio test was used. CFA demonstrates that M0 (df = 188, χ2 = 393.38, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94 RMSEA = 0.07 SRMR = 0.05) was a significantly better fit than M1 (df = 189, χ2 = 1516.50, CFI = 0.77, TLI = 0.74, RMSEA = 0.15, SRMR = 0.10). Consistent with the results of the first survey, the unidimensionality of both OI and ODI constructs was found in the second data.

Table 7.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses Results (n = 218).

| Item | Factor loading | AVE | CR | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Identification | 0.68 | 0.96 | 0.97 | |

| OI1 | 0.81 | |||

| OI2 | 0.86 | |||

| OI3 | 0.87 | |||

| OI4 | 0.79 | |||

| OI6 | 0.89 | |||

| OI7 | 0.83 | |||

| OI8 | 0.79 | |||

| OI10 | 0.85 | |||

| OI11 | 0.85 | |||

| OI12 | 0.90 | |||

| OI14 | 0.58 | |||

| Organizational Disidentification | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.94 | |

| ODI1 | 0.81 | |||

| ODI2 | 0.58 | |||

| ODI4 | 0.87 | |||

| ODI6 | 0.80 | |||

| ODI9 | 0.89 | |||

| ODI11 | 0.86 | |||

| ODI12 | 0.75 | |||

| ODI13 | 0.83 | |||

| ODI14 | 0.68 | |||

*AVE – average variance extracted, CR – composite reliability, α – Cronbach alpha.

The criteria for convergent validity and discriminant validity were sufficient (Campbell and Fiske, 1959). The composite reliabilities were large (CROI = 0.96, CRODI = 0.94). Significant factor loadings of both measures ranged from 0.58 to .90. and composite reliability scores exceeded 0.7 (Helms et al.,2006). The split-half reliability coefficient of OI measure was 0.93 s by and that of ODI was 0.91 by the Spearman-Brown formula. Internal consistency and split-half reliability analysis showed strong consistency of the items of the scales and gave satisfactory results. Also, AVE of each of the latent constructs exceeded the minimum criterion of .50 (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). Discriminant validity is also established. Factor correlation between OI and ODI was -0.68 and it did not exceed 0.85 (Kline, 2005). The square root of the AVE of each latent variable is greater than the correlation coefficients between that latent variable and other latent variables (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The Cronbach’s alphas for both measures were all well above the minimum value of 0.7 (Field, 2013).

A criterion validity test of the measure was tested to assess if the developed measures can predict a certain construct that it should theoretically be able to predict. Previously scholars found perceived organizational support (POS) was significantly related to OI (e.g., Cheung and Law, 2008; Sluss et al., 2008; Edwards and Peccei, 2010) and ODI was significantly related to turnover intention (e.g., Lai et al., 2013; Bentein et al., 2017). POS was measured by taking five items developed by Eisenberger et al. (1986) and turnover intention was measured with three items developed by Lang et al. (2007). The results of the SEM using Mplus 7.2 showed that the relationships between two constructs and an additional constructs, POS was positively linked to OI (γ = .83), the turnover intention was positively linked to ODI (γ = .73), indicating that the finalized measures predict as expected in relation to the additional construct (Churchill, 1979).

5. Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this study was to develop reliable and valid measures of OI and ODI that can be used for food service workers. Foodservice has unique characteristics that are even different from other hospitality industries. To do this, existing measures were reviewed and modified. The results from personal interviews confirmed the statements of previous measures. Also, five new items were generated through the interviews. The findings of this study suggest that the final measures of OI and ODI using the categorical dimension approach are one-dimensional, reliable, and valid.

5.1. Theoretical implications

This study affects scholars and practitioners in the foodservice industry. In developing the OI and ODI measures, the present study contributes to the theoretical understanding and measurement of OI and ODI in foodservice settings. This study represents the first attempt to develop reliable and valid OI and ODI measures for assessing employees’ psychological attachment and separation in the foodservice industry. These measurements can be used to predict employees’ attitudes, behaviors in the organization (e.g., organizational citizenship behavior), behavioral intention, and commitment. Among 20 items, 5 additional items consisting of 3 OI and 2 ODI items are generated through personal interviews with restaurant employees. These new measures using the mixed method help capture employees’ attachment or detachment with the organization in the restaurant industry precisely. For example, a new measure (“When I see positive (online) guest comments, I am proud of being part of XXX.”), compared with an existing measure (“When someone praises XXX, it feels like a personal compliment”) provides a concrete example, such that respondents can easily judge whether to agree or disagree.

The results of this study confirm the unidimensionality of OI and ODI measures. Results from EFA and CFA show that a single dimension can appropriately capture the scope of employees’ OI and ODI in foodservice. Therefore, restaurant researchers are recommended to use a unidimensional measure when studying social identity. Results also show that OI and ODI can be unique constructs. The two factors are correlated but support discriminability. Thus, they may have unique drivers or outcomes; thus, each construct should be managed separately. Further analysis with related variables is required to confirm if OI and ODI are unique constructs with separate drivers and outcomes. Besides, to date, the role of ODI in organizational settings remains unclear. Most studies have focused on the negative side of ODI. However, ODI may have positive functions in organizational settings. These measures may help shed light on the role of ODI in the organization.

5.2. Practical implications

Practically, inducing OI and decreasing ODI may help achieve a competitive advantage in the hospitality industry. Employees who strongly identify with their organization may perform work duties beyond formal role requirements discretionarily (Smith et al., 1983) which may increase service quality significantly. Foodservice organizations can use these scales to assess, plan, and track employees’ psychological attachment and detachment with the organization. Based on the assessment, organizations can develop strategies for allocating their resources to critical aspects efficiently to manage employees’ organizational attitudes or behaviors. Therefore, restaurant operators can develop sophisticated staff training and operating systems that can lead to improved attitudes or behaviors for employees. Checking OI and ODI regularly can be beneficial to the organization manage employees’ attitudes and behaviors.

5.3. Limitations and future research opportunities

This study has several limitations. First, web-based surveys using MTurk are conducted to collect data only on current restaurant employees in the USA. Employees’ emotional experiences and perceptions of the organization can differ based on the type of concept or location. The current study collects data from the employees who are working at various F&B concepts. Some items on the developed scales may be essential in one segment of the foodservice industry, but they may not be essential in another segment. Moreover, large chain restaurant brands and single-unit restaurants may have different items to measure their social identity factors because they may have different levels of supports and benefits. Therefore, interpreting and generalizing the results of research in other industries should be performed carefully. Future studies should include a moderating analysis of restaurant segments, employment type, or brand size. Also, possibly, there are differences in the level of OI or ODI between tipped and non-tipped employees since most tipped employees' income comes directly from consumers. Furthermore, a comparison of employees’ OI and ODI from countries with and without tip culture within a global brand can show interesting results. Besides, currently, food service workers are experiencing extreme employment insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This phenomenon can change employee attachment to the organization. Also, the OI and ODI of employees between furloughed and laid off can be different. A qualitative study can be conducted to explore the foodservice workers' psychological status during this pandemic.

An important next step for researchers is to identify the drivers and outcomes of OI and ODI. Restaurant operators may have difficulty in directly managing the level of OI and ODI. Thus, identifying the factors that can increase employees’ psychological attachment or detachment is crucial for them to set their operation strategies. Moreover, knowing the outcomes of OI and ODI can help restaurant operators allocate their limited resources to appropriate places.

References

- Abdi Hervé. Partial least square regression (PLS regression) Encyclopedia for research methods for the social sciences. 2003;6(4):792–795. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.C., Gerbing D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988;103(3):411. [Google Scholar]

- Despite more tech, you will have to wait even longer for a Big Mac. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.com/f/610518/mcdonalds-tech-pushes-are-putting-more-on-its-employees-plates-and-its-pushing/.

- 2019 Restaurant industry factbook. (2019). Retrieved from https://restaurant.org/Downloads/PDFs/Research/SOI/restaurant_industry_fact_sheet_2019.pdf.

- Economic News Release. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.t18.htm.

- 7 Restaurant Scheduling Stats of 2017 [Infographic]. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.7shifts.com/blog/restaurant-scheduling-stats-of-2017/.

- Ashforth B.E., Mael F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989;14(1):20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz A., Goldman H.M., Olsen N. Facets of type a personality and pay increase among the employees of fast food restaurants. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 2007;26(3):754–758. [Google Scholar]

- Becker J.C., Tausch N. When group memberships are negative: the concept, measurement, and behavioral implications of psychological disidentification. Self Identity. 2014;13(3):294–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bentein K., Guerrero S., Jourdain G., Chênevert D. Investigating occupational disidentification: a resource loss perspective. J. Managerial Psychol. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya C.B., Sen S. Consumer-company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003;67(2):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K.A., Hoyle R.H. Perceived cohesion: a conceptual and empirical examination. Soc. Forces. 1990;69(2):479–504. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne H., Jenkins M. Eliciting managers’ personal values: an adaptation of the laddering interview method. Organ. Res. Methods. 2005;8(4):410–428. [Google Scholar]

- Brown E.A., Thomas N.J., Bosselman R.H. Are they leaving or staying: a qualitative analysis of turnover issues for generation Y hospitality employees with a hospitality education. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 2015;46:130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J.E. A three-factor model of social identity. Self Identity. 2004;3(3):239–262. [Google Scholar]

- Chang K., Kuo C.C., Su M., Taylor J. Dis-identification in organizations and its role in the workplace. Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations. 2013;68(3):479–506. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney G. Department of Communication, Purdue University; 1982. Organizational Identification As Process And Product: A Field Study. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M.F., Law M.C. Relationships of organizational justice and organizational identification: the mediating effects of perceived organizational support in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Bus. Rev. 2008;14(2):213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaburu D.S., Byrne Z.S. Predicting OCB role definitions: exchanges with the organization and psychological attachment. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009;24(2):201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979;16(1):64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Costas J., Fleming P. Beyond dis-identification: a discursive approach to self-alienation in contemporary organizations. Hum. Relations. 2009;62(3):353–378. [Google Scholar]

- DiSanza J.R., Bullis C. “Everybody identitiefies with Smokey the bear” employee responses to newsletter identification inducements at the US forest service. Manag. Commun. Q. 1999;12(3):347–399. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J.E., Dukerich J.M., Harquail C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994:239–263. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M.R. Organizational identification: a conceptual and operational review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005;7(4):207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M.R., Peccei R. Perceived organizational support, organizational identification, and employee outcomes. J. Personnel Psychol. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R., Huntington R., Hutchison S., Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986;71(3):500. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N., Spears R., Doosje B. Oxford; 1999. Social Identity. p. 144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsbach K.D., Bhattacharya C.B. Defining who you are by what you’re not: organizational disidentification and the national rifle association. Organ. Sci. 2001;12(4):393–413. [Google Scholar]

- Field A. Sage; 2013. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbing D.W., Anderson J.C. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988;25(2):186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Anderson R.E., Tatham R.L., Black W.C. Prentice-Hall; New Jersey: 1998. Multivariate Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg M.A., Terry D.I. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000;25(1):121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson G.D., Sofroniou N. Sage; 1999. The Multivariate Social Scientist: Introductory Statistics Using Generalized Linear Models. [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami T., Ishida Y. Status hierarchy and the role of disidentification in the discriminatory perception of outgroups 1. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2007;49(2):136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Josiassen A. Consumer disidentification and its effects on domestic product purchases: an empirical investigation in the Netherlands. J. Mark. 2011;75(2):124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter D.L., Mirvis P.H. Jossey-Bass; 1989. The Cynical Americans: Living and Working in an Age of Discontent and Disillusion. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman H.C. Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. J. Conflict Resolution. 1958;2(1):51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R.B. 2005. Methodology in the Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner G.E. Operationalizing and testing the expanded model of identification. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2002;2002(1):H1–H6. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner G.E., Ashforth B.E. Evidence toward an expanded model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav.: Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2004;25(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lai J.Y., Chan K.W., Lam L.W. Defining who you are not: the roles of moral dirtiness and occupational and organizational disidentification in affecting casino employee turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 2013;66(9):1659–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence B., Kaufmann P.J. Identity in franchise systems: the role of franchisee associations. J. Retailing. 2011;87(3):285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Lawshe C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity 1. Pers. Psychol. 1975;28(4):563–575. [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.S., Park T.Y., Koo B. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015;141(5):1049. doi: 10.1037/bul0000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long E. 2018. Serving up Better Wages for Restaurant Workers. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst R. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Key methods in geography. 2003;3(2):143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lusch R.F., Harvey M.G. Opinion: the case for an off-balance-sheet controller. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1994;35(2):101. [Google Scholar]

- Mael F., Ashforth B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992;13(2):103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mael F.A., Ashforth B.E. Identification in work, war, sports, and religion: contrasting the benefits and risks. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2001;31(2):197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Mael F.A., Tetrick L.E. Identifying organizational identification. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1992;52(4):813–824. [Google Scholar]

- Milkovich G.T., Newman J.M. Irwin; 1999. Compensation. [Google Scholar]

- Miller V.D., Allen M., Casey M.K., Johnson J.R. Reconsidering the organizational identification questionnaire. Manag. Commun. Q. 2000;13(4):626–658. [Google Scholar]

- Nadiri H., Tanova C. An investigation of the role of justice in turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 2010;29(1):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J.C. 2d ed. McGraw-Hill; 1978. Psychometric Theory. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly C.A., Chatman J. Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: the effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986;71(3):492. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne J.W. Race and academic disidentification. J. Educ. Psychol. 1997;89(4):728. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt M.G. The good, the bad, and the ambivalent: managing identification among Amway distributors. Adm. Sci. Q. 2000;45(3):456–493. [Google Scholar]

- Riketta M., Van Dick R., Rousseau D.M. Employee attachment in the short and long run: antecedents and consequences of situated and deep-structure identification. Z. Personalpsychologie. 2006;5(3):85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir B., Kark R. A single-item graphic scale for the measurement of organizational identification. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004;77(1):115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Shimp T.A., Sharma S. Consumer ethnocentrism: construction and validation of the CETSCALE. J. Mark. Res. 1987;24(3):280–289. [Google Scholar]

- Silver M.D. The Ohio State University; 2001. The Multidimensional Nature of Ingroup Identification Correlational and Experimental Evidence (Doctoral Dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- Sluss D.M., Klimchak M., Holmes J.J. Perceived organizational support as a mediator between relational exchange and organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008;73(3):457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.A., Organ D.W., Near J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983;68(4):653. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Human groups and social categories: studies in social psychology. CUP Archive. 1981 [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.C. Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. 1982. Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela D., Shrivastava P. Southern Cross University and the Southern Cross Institute of Action Research (SCIAR); 2002. Interview as a Method for Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dick R., Christ O., Stellmacher J., Wagner U., Ahlswede O., Grubba C., Tissington P.A. Should I stay or should I go? Explaining turnover intentions with organizational identification and job satisfaction. Br. J. Manag. 2004;15(4):351–360. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg D. Work motivation and performance: a social identity perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2000;49(3):357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg D., Van Schie E.C. Foci and correlates of organizational identification. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000;73(2):137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M., Yildiz A.A. National (dis) identification and ethnic and religious identity: a study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007;33(10):1448–1462. doi: 10.1177/0146167207304276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkl K.E. Identification with the school. Am. J. Educ. 1997;105(3):294–318. [Google Scholar]

- Wann D.L., Branscombe N.R. Sports fans: measuring the degree of identification with their team. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Whetten D.A., Godfrey P.C., editors. Identity in Organizations: Building Theory Through Conversations. Sage; 1998. pp. 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Wolter J.S., Brach S., Cronin J.J., Jr., Bonn M. Symbolic drivers of consumer-brand identification and disidentification. J. Bus. Res. 2016;69(2):785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Zou X., Morris M.W., Benet-Martínez V. Identity motives and cultural priming: cultural (dis) identification in assimilative and contrastive responses. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008;44(4):1151–1159. [Google Scholar]