Introduction

Residents' discrimination against tourists has long been a major problem. Previous studies have documented discrimination in products and pricing strategies against tourists (Sharifi-Tehrani et al., 2013). Tourists have also been harassed by locals when they are seen as loud and unreasonable (Tung et al., 2020). Discrimination against tourists through low levels of threats (e.g., anti-tourist messages) and extreme violence (e.g., physical attacks) have] been reported (Cheung & Li, 2019). Discrimination in Airbnb accommodation (Farmaki & Kladou, 2020), and against Mainland Chinese tourists in Hong Kong have also been examined (Ye et al., 2013).

With the COVID-19 pandemic, reports of discrimination have further exacerbated and discrimination against Chinese tourists have spread as quickly as the disease (Devakumar et al., 2020). In South Korea, some business owners have barred Chinese from private establishments (Fottrell, 2020). In Japan, residents may avoid contact with Chinese (Ipsos MORI, 2020). In England, abuses against Chinese in public have been reported (Preston-Ellis, 2020). These actions have sparked a deluge of concerns about host-guest relations and the broader challenges of managing discrimination between social groups.

The purpose of this research note is to connect the concept of perceived everyday discrimination with discriminatory responses against tourists. Everyday discrimination is a subset of general discrimination because it reflects thoughts and beliefs about experiencing discrimination that are chronic or episodic but generally minor (Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Everyday discrimination is not restricted to tourists, and even individuals living within the same community (i.e. residents) could experience discrimination. For instance, residents could be discriminated against when they interacted with others on a daily basis in various contexts based on their perceived social categorical membership (e.g., Asian Americans and African Americans). The existing of social categorization differentiates residents into ‘us’ and ‘them’, which could stimulate discriminatory actions. Tourists, due to more obvious social differences, could experience more discrimination compared to residents. Despite the popularity in using everyday discrimination to investigate social-psychological intergroup relations, to authors' best knowledge, it has not yet been examined in the tourism context. The resident-to-resident everyday discrimination (i.e., by Americans against their fellow residents) reflects residents' social dynamics and could serve as a reference on social group relations. It is possible that residents could project such discriminatory dynamics onto tourists for the sake of assimilation needs against an outside reference group. Such actions could affect host-guest relations that are important for a sustainable tourism development.

This research note uncovers the relationships between (1) everyday discrimination perceived by residents, (2) the types of harmful actions they may perform on tourists, and (3) their support for further discriminatory responses against tourists in the context of a major societal event (i.e., in this case, COVID-19). For instance, would residents who perceive everyday discrimination be more sympathetic, and less likely to, discriminate against others (i.e., tourists)? Conversely, having perceived everyday discrimination in their own lives, would they project their own discriminatory responses against those (i.e., tourists) that they see as a substantive outgroup?

This study provides initial evidence that residents who perceive everyday discrimination are more likely to adopt harmful and discriminatory responses against tourists. For instance, residents who reported everyday discrimination (e.g., been called names or insulted) were more likely to have performed harmful actions against tourists (e.g., be unfriendly or mock a tourist) and support further discriminatory responses amidst COVID-19 (e.g., exclude tourists from public and private spaces). Residents were not more sympathetic to discrimination after having perceived discrimination themselves; instead, there was a significant relationship from everyday discrimination to supporting harmful and discriminatory responses against tourists.

Methods

An online survey was conducted with American citizens in early February 2020, near the beginning of COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. A 50–50 gendered, non-student sampling approach was adopted. Nine items were used to measure perceived everyday discrimination (Williams et al., 1997) on a 4-point frequency scale. Twelve items were used to assess residents' facilitative or harmful actions against tourists on a 7-point agreement scale. Six discriminatory responses against Mainland Chinese tourists that have been reported since the COVID-19 outbreak were evaluated on a 7-point agreement scale.

Findings

203 surveys were collected (49.8% female; 59.6% between 25 and 44 years old). Composite reliabilities (CR) for the three measurements exceeded 0.70 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 show the means and standard deviations for all the actual items in the study.

Table 1.

Perceived everyday discrimination among Americans.

| Itemsa | CR | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Everyday discrimination | 0.921 | ||

| Others act as if they are better than you | 2.094 | 0.993 | |

| Treated with less courtesy than others | 1.897 | 0.936 | |

| Treated with less respect than others | 1.862 | 0.960 | |

| Others act as if you are not smart | 1.803 | 0.939 | |

| Receive poorer services | 1.729 | 0.918 | |

| Others act as if they are afraid of you | 1.700 | 0.897 | |

| Been called names or insulted | 1.675 | 0.919 | |

| Others act as if you are dishonest | 1.675 | 0.935 | |

| Been threatened or harassed | 1.606 | 0.891 |

Measured on a 4-point scale from 1 = never to 4 = often.

Table 2.

Americans' facilitative or harmful actions against Mainland Chinese tourists.

| Itemsa | CR | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitation | 0.930 | ||

| Start a conversation with tourist | 3.823 | 1.813 | |

| Socialize with tourist | 3.980 | 1.816 | |

| Interact with tourist | 3.897 | 1.871 | |

| Tolerate a tourist | 4.143 | 1.863 | |

| Accept a tourist | 4.163 | 1.877 | |

| Endure a tourist | 3.951 | 1.858 | |

| Harm | 0.924 | ||

| Be unfriendly to tourist | 2.064 | 1.577 | |

| Mock a tourist | 1.926 | 1.554 | |

| Perform threatening actions to tourist | 1.970 | 1.616 | |

| Resist to help tourist in need | 2.369 | 1.754 | |

| Reluctant to help tourist in need | 2.379 | 1.709 | |

| Refrain from helping tourist in need | 2.360 | 1.759 |

Measured on a 7-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Table 3.

Discriminatory responses against Mainland Chinese tourists during COVID-19.

| Itemsa | CR | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discriminatory responses | 0.911 | ||

| Separate at the border | 4.064 | 1.995 | |

| Screen individually at the border | 4.631 | 1.979 | |

| Avoid contacts | 3.946 | 2.097 | |

| Exclude from public spaces | 3.517 | 2.062 | |

| Exclude from private spaces | 3.453 | 2.013 | |

| Prohibit to enter my country | 3.734 | 2.101 |

Measured on a 7-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

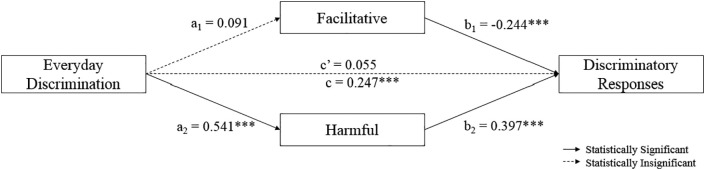

A significant positive relationship (c = 0.247, p < 0.001) between everyday discrimination (X) to discriminatory responses against tourists (Y) was identified. Parallel mediation analysis using SPSS Process v3.3 (Hayes, 2013) was adopted to evaluate the mediating effects of residents' facilitative or harmful actions. Everyday discrimination has a significant positive link with harmful actions (a2 = 0.541, p < 0.001). Harmful actions also induced further discriminatory responses against tourists (b2 = 0.397, p < 0.001). A 95% confidence level based on 10,000 bootstrap samples indicated a significant indirect effect through harmful actions (a2b2 = 0.215, 95%CI [0.118, 0.331]) (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Mediation analysis of proposed model.

The results indicate significant positive relationship among the three constructs, suggesting that residents who perceived everyday discrimination were more likely to endorse harmful and discriminatory responses against tourists. This is a worrisome phenomenon in society, especially with increasing intergroup conflicts given the outbreak of COVID-19 as being discriminated against could potentially elicit further discrimination against other individuals. A possible explanation could be residents who perceived everyday discrimination may readily discriminate against others who are more obvious outgroup members to address assimilation motives within their communities. This could allow them to share similarities as residents against a common outgroup. Another possible explanation is that residents may endorse a certain extent of discrimination to display the perceived social hierarchy of locals over tourists, indicating residents' superiority.

Discrimination may become particularly salient after COVID-19. Wealth disparities and inequalities among individuals may increase as income and discretionary spending tightens (United Nation, 2020). Consequently, those who can travel internationally could be seen as ‘haves’ versus a large segment of the resident population of ‘have nots’. Notions of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ could intensify, leading to negative sentiments, discrimination, and social intolerance.

This study contributes by highlighting the complexity of host-tourist dynamics beyond the interactions between residents and tourists, extending to the dynamics among residents within the same community. The findings suggest that residents' perceived everyday discrimination could have a spillover effect on tourists, which offers a novel perspective in studies of host-guest relations. More importantly, the study draws attention for the potential to take into account the broader societal views of everyday discrimination in future tourism studies.

Additionally, the resident-tourist intergroup relation is critical for fostering positive host-guest relations and sustainable tourism development. While existing studies have mainly focused on resident-tourist conflicts (Chien & Ritchie, 2018), this study provides a different angle on the influence of resident-to-resident's everyday discrimination on subsequent resident-to-tourist relations. As this study suggests, there is an interesting connection between how residents perceived discrimination by their fellow citizens in everyday lives and how they subsequently treat tourists.

Practically, this study offers insights to tourism officials on the importance of promoting mutual understanding between social groups (i.e., resident-resident, and resident-tourist) (Maruyama & Woosnam, 2015). Policymakers are encouraged to take action against domestic discrimination as the development of host-guest relations from a tourism perspective could also be influenced by the social dynamics among residents.

A limitation of this study is that it measures residents' perceived everyday discrimination based on residents' subjective views of their daily interactions with other residents. Although perceived everyday discrimination has been widely employed in intergroup studies, future research could replicate this study by examining the actual everyday discrimination experienced by residents within their communities.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The work described in this article was fully supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. PolyU255017/16B).

Biographies

Serene Tse is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research focuses on host-tourist relations, tourist stereotypes, resident behaviours, and destination management.

Vincent Wing Sun Tung is an Associate Professor at the School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. His research focuses on host-tourist relations, social issues, stereotypes, and tourism experiences.

Associate editor: Yang Yang

References

- Cheung K.S., Li L.H. Understanding visitor–resident relations in overtourism: Developing resilience for sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2019;27(8):1197–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Chien P.M., Ritchie B.W. Understanding intergroup conflicts in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 2018;72(C):177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar D., Shannon G., Bhopal S.S., Abubakar I. Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10231):1194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki A., Kladou S. Why do Airbnb hosts discriminate? Examining the sources and manifestations of discrimination in host practice. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2020;42:181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Fottrell Q. ‘No Chinese allowed’: Racism and fear are now spreading along with the coronavirus. 2020. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/no-chinese-allowed-racism-and-fear-are-now-spreading-along-with-the-coronavirus-2020-01-29 Retrieved May 04, 2020, from MarketWatch Web site.

- Hayes A.F. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos MORI COVID-19 – One in seven people would avoid people of Chinese origin or appearance. 2020. https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/covid-19-one-seven-people-would-avoid-people-chinese-origin-or-appearance Retrieved May 05, 2020, from Ipsos MORI Web site.

- Maruyama N., Woosnam K.M. Residents’ ethnic attitudes and support for ethnic neighborhood tourism: The case of a Brazilian town in Japan. Tourism Management. 2015;50:225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Preston-Ellis R. Asian teens, punched, kicked and spat at in three separate racist coronavirus attacks in Exeter in just one day. 2020. https://www.devonlive.com/news/devon-news/asian-teens-punched-kicked-spat-3922546 Retrieved May 04, 2020, from DevonLIVE Web site.

- Sharifi-Tehrani M., Verbič M., Chung J.Y. An analysis of adopting dual pricing for museums: The case of the national museum of Iran. Annals of Tourism Research. 2013;43:58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tung V.W.S., King B.E.M., Tse S. The tourist stereotype model: Positive and negative dimensions. Journal of Travel Research. 2020;59(1):37–51. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation. (2020). COVID-19 likely to shrink global GDP by almost one per cent in 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020 from United Nation Web site: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2020/04/covid-19-likely-to-shrink-global-gdp-by-almost-one-per-cent-in-2020/.

- Williams D.R., Mohammed S.A. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Yu Y., Jackson J.S., Anderson N.B. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B.H., Zhang H.Q., Yuen P.P. Cultural conflicts or cultural cushion? Annals of Tourism Research. 2013;43:321–349. [Google Scholar]