Abstract

This study details a case of biotinidase deficiency mimicking neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders and reviews prior cases of biotinidase deficiency that met Wingerchuck 2015 criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

Biotinidase deficiency (BD) is a rare, autosomal recessive, metabolic disorder associated with mutations in the BTD gene. Clinical features are heterogenous, although optic neuropathy and myelitis have been reported in children.1,2,3,4,5,6 These clinical features can mimic neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD), which are rare in children. To our knowledge, no prior studies have analyzed shared clinical findings among this patient population. Here, we present what is, to our knowledge, only the second case of BD mimicking NMOSD without elevated lactate, and review prior cases of BD that met Wingerchuck 2015 criteria for NMOSD.

Report of a Case

A 13-year-old healthy girl presented with simultaneous paraparesis and bilateral vision loss. Visual acuity was 20/400 OU, and optic pallor was present bilaterally. Clinical and imaging history are presented in the Table and Figure. For a presumed diagnosis of NMOSD, the patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone but worsened with treatment and had immunotherapy ceased.

Table. Comparator Pediatric Cases of Optic Neuritis and Myelitis Meeting Criteria for NMOSD.

| Variable | Study case | All cases (n = 10), No./total No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at onset, y | 13 | Mean (range), 9.2 (4-15) |

| Sex, male/female | 0/1 | 6/4 |

| Prior DD? | No | 0/10 (0) |

| ON and spinal involvement | Yes | 10/10 (100) |

| LETM on neuroimaging | Yes | 9/9 (100) |

| Non-ON or C-spine WM lesions on neuroimaging | No | 2/6 (17)a |

| Seizure | No | 2/10 (20)b |

| CSF pleocytosis | No | 0/6 |

| OCB present and/or elevated IgG index | No | 2/3 (66) |

| Elevated lactate (serum or CSF) | No (serum + CSF) | 8/10 (80) |

| Autoantibody positivity (AQP4/MOG) | Negative (AQP4 and MOG) | 0/3 |

| Dermatologic disease | Yes (dermatitis) | 4/10 (40) With dermatitis; 2/10 (20) with alopecia and dermatitis |

| BEA level, nmol/min/mL | <0.10 | Mean (range), 0.16 (0-0.58) |

| BTD gene abnormalities | Homozygous c.1330G>C (p.A444H) ; heterozygous c.1207T>G (p.F403V) ; heterozygous c.814T>G (p.T272G) |

8/10 (80) Patients tested; Girard et al1: c.643C>T (pL215F) and c.1612C>T (p.R538C); Raha et al2: homozygous c.133C>T (p.H447Y); Wolf et al, Pt 14: homozygous c.1369G>A (p.V457M); Wolf et al, Pt 24: heterozygous c.643C>T (p.L215F) and heterozygous c.1186T>C (p.S366P); Wolf et al, Pt 34: homozygous c.1612C>T (p.R538C); Wolf et al, Pt 44: G98:d7i3 c.643C>T (p.L215F); Yilmaz et al5: c.98-104delinsTCC p.V457M |

| Improvement with immune therapy? | No | 2/5 (40)c |

| Worsening with immune therapy? | Yes; decline associated with corticosteroids | 2/5 (40); Decline with corticosteroids and/or plasmapheresis |

| Relapses not receiving biotin | No | 8/10 (80)d |

| Relapses receiving biotin | No | 0/10 |

| Clinical improvement receiving biotin | Yese | 10/10 (100)e |

Abbreviations: AQP4, aquaporin-4 antibody; BEA, biotin enzyme activity; CC, corpus callosum; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; C-spine, cervical spine; DD, developmental delay; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; LETM, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, defined as TM extending >3 vertebral bodies in length; MOG, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; NA, not applicable; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; OCB, oligoclonal bands; ON, optic nerve; SP, septum pellucidum; WM, white matter.

CC, fornix, medulla, medial thalamusy, and SP reported.

All prior to onset of ON/LETM.

Corticosteroids and/or IVIg.

Of the 8 patients with relapse, 7 had ON/LETM phenotype and 1 had LETM-only phenotype.

The patient in this study reported improved visual acuity with residual ON atrophy. All other cases experienced improved vision and paraparesis; residual ON atrophy reported in 2 of 10 (20).

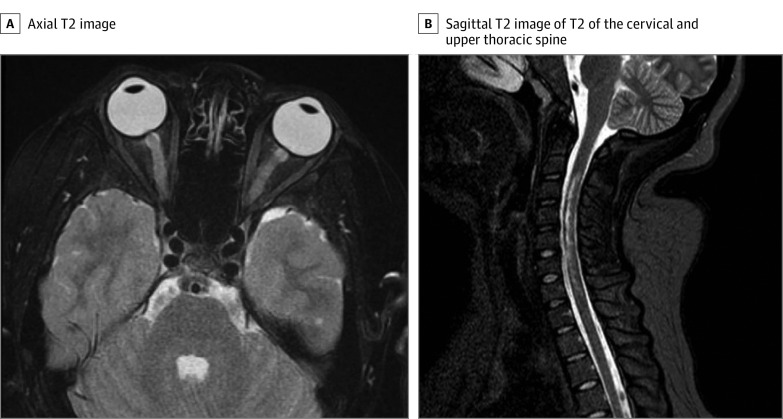

Figure. Neuroimaging Studies at Diagnosis.

A, Axial T2 demonstrating bilateral signal prolongation in the optic nerves. There was no associated postcontrast enhancement of the optic nerves. B, Sagittal T2 of the cervical and upper thoracic spine demonstrating signal patchy signal prolongation throughout the upper spine. On postcontrast imaging, cervical lesions were noted to have patchy and heterogenous signal throughout the cervical cord in the same distribution as T2 signal prolongation.

The patient regained her motor skills over 6 months but had stagnant visual deficits (20/400 OU). Repeated imaging at 1 year showed resolution of signal in the spinal cord and optic nerve atrophy. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid studies remained unremarkable; however, profound biotinidase enzyme activity (BEA) deficiency was identified, as were 3 mutations in the BTD gene (Table). The patient was treated with biotin supplementation (100 mg daily, >1000 × typical multivitamin content) and noted improvement in her visual acuity at 3 months (20/200 OS and 20/100 OD). She continues receiving biotin therapy and has had no further relapses.

Results

Summarized clinical data for children with clinical presentations consistent with NMOSD but found to have BD are presented in the Table. There was no response to immunomodulatory therapy in 3 of 5 cases (60%), and 2 patients had clinical declines associated with treatment. Initial attacks were more likely to demonstrate improvement with immune therapy as opposed to latter relapses. Despite late clinical presentations, all patients had profoundly low BEA (average, 0.16 nmol/min/mL). Genetic mutations of the BTD gene were heterogenous, although 2 patients were noted to have shared mutations (c.1612C>T [p.R538C]). All patients improved with administration of biotin (vision and paresis), and no patient had relapses once beginning supplementation.

Discussion

This case highlights an expanding clinical and genetic spectrum of BD, with increasing overlap of patients with neuroimmunologiclike phenomenon and relapses. Prior reports of isolated optic neuropathy and persons with myelitis with BD exist, although only a minority present with optic neuropathy and myelitis simultaneously.1,2,3,4,5,6

In this review, several clinical features stand out. First, all patients tested had low BEA, although none had developmental delay or epilepsy, as is reported in profound BD.4 It is unclear why neonatal screening for cases within the United States would have not detected these patients, invoking the possibility of an epigenetic phenomenon being present. All patients tested were autoantibody negative, without cerebrospinal pleocytosis, and had clinical courses marked by relapses, with 80% of patients having lactic acidosis, yielding a unique profile from NMOSD. Oligoclonal bands were intermittently present in 2 of 3 cases tested, although this is of unclear significance. Most patients did not respond to immunotherapy in the acute or maintenance periods.3,5 Finally, 2 patients in this review are noted to have similar genetic mutations (c.1612C>T [p.R538C]). It is possible this mutation may yield an NMOSD phenotype, although BEA was not reported in 1 case, making extrapolation difficult.

Correct diagnosis of BD can prevent ocular and spinal disability when identified early and treated aggressively.4 Features of elevated serum or cerebrospinal lactate, absence of cerebrospinal pleocytosis, and aquaporin-4/myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody negativity in a child with NMOSD clinical phenotype should prompt evaluation for BD. Further, use of immunomodulatory therapies may cause clinical worsening, although modest steroid responsiveness has been reported.2,3

References:

- 1.Girard B, Bonnemains C, Schmitt E, Raffo E, Bilbault C. Biotinidase deficiency mimicking neuromyelitis optica beginning at the age of 4: a treatable disease. Mult Scler. 2017;23(1):119-122. doi: 10.1177/1352458516646087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raha S, Udani V. Biotinidase deficiency presenting as recurrent myelopathy in a 7-year-old boy and a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45(4):261-264. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y, Li C, Qi Z, et al. Spinal cord demyelination associated with biotinidase deficiency in 3 Chinese patients. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(2):156-160. doi: 10.1177/0883073807300307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf B, Pomponio RJ, Norrgard KJ, et al. Delayed-onset profound biotinidase deficiency. J Pediatr. 1998;132(2):362-365. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70464-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yilmaz S, Serin M, Canda E, et al. A treatable cause of myelopathy and vision loss mimicking neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: late-onset biotinidase deficiency. Metab Brain Dis. 2017;32(3):675-678. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-9984-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman S, Standing S, Dalton RN, Pike MG. Late presentation of biotinidase deficiency with acute visual loss and gait disturbance. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39(12):830-831. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]