This randomized clinical trial evaluates the effectiveness of a multilevel home- and school-based asthma educational program compared with a school-based asthma educational program alone in improving asthma outcomes in children enrolled in Head Start.

Key Points

Question

Is a multilevel home and preschool asthma educational program more effective in improving asthma control compared with a preschool-based program alone?

Findings

In a randomized clinical trial of 398 participants conducted at Head Start programs, preschool-aged children with asthma whose caregivers received a multilevel home- and school-based asthma educational program had improved asthma control, fewer hospitalizations, and fewer courses of oral corticosteroids at 12 months compared with children whose caregivers received a school-based educational program only.

Meaning

Multilevel interventions implemented in community settings that serve at-risk families may be key to reducing disparities in asthma outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Asthma is the most common chronic childhood disease, with Black children experiencing worse morbidity and mortality. It is important to evaluate the effectiveness of efficacious interventions in community settings that have the greatest likelihood of serving at-risk families.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of a multilevel home- and school (Head Start)–based asthma educational program compared with a Head Start–based asthma educational program alone in improving asthma outcomes in children.

Design, Setting, and Participant

This randomized clinical trial included 398 children with asthma enrolled in Head Start preschool programs in Baltimore, Maryland, and their primary caregivers. Participants were recruited from April 1, 2011, to November 31, 2016, with final data collection ending December 31, 2017. Data were analyzed from March 18 to August 30, 2018.

Interventions

Asthma Basic Care (ABC) family education combined with Head Start asthma education compared with Head Start asthma education alone.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Asthma control as measured by the Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK) score.

Results

Among the 398 children included in the analysis (247 boys [62.1%]; mean [SD] age, 4.2 [0.7] years), the ABC plus Head Start program improved asthma control (β = 6.26; 95% CI, 1.77 to 10.75; P < .001), reduced courses of oral corticosteroids (β = −0.61; 95% CI, −1.13 to −0.09; P = .02), and reduced hospitalizations (odds ratio, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.21-0.61; P < .001) during a 12-month period.

Conclusion and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, combined family and preschool asthma educational interventions improved asthma control and reduced courses of oral corticosteroids and hospitalizations. Multilevel interventions implemented in community settings that serve low-income minority families may be key to reducing disparities in asthma outcomes.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01519453

Introduction

Despite advances in asthma therapies and the widespread dissemination of asthma clinical guidelines, low-income, minority children have disproportionately high morbidity and mortality due to asthma.1,2 Among children with asthma, preschool-aged children have the highest risk for use of health care services. Research shows that health disparities begin early in children’s lives and that these early health risks can have long-range implications.3,4,5 Because the causes of asthma disparities are multifaceted,6 the strategies necessary to reduce asthma health disparities will require innovative, multimodal interventions that are tailored to the unique barriers faced by low-income minority families.6

Previous efficacy studies have suggested that asthma educational programs are effective in improving overall management of asthma for preschool children.4,7 Otsuki et al8 found that a cultural- and literacy-tailored family asthma educational intervention (Asthma Basic Care [ABC]) significantly increased symptom-free days and reduced oral corticosteroid (OCS) use for 18 months, relative to usual care, among children with asthma who presented to the emergency department (ED). However, the ABC educational intervention has not been broadly implemented for evaluation of effects on population health.9

For promising asthma interventions to have a sustainable public health influence for low-income, minority children, they must be integrated within community structures that serve these young, high-risk children.10 Head Start is a federally funded national program that provides preventive health services and screening to low-income preschool students by engaging and empowering parents, thus representing an ideal community setting for disseminating asthma education early in life.11,12 Maryland Head Start is one of the largest child care providers for low-income families in the state, making Head Start a community setting that can offer widespread implementation of asthma programs.

This project evaluated the effectiveness of a family asthma educational program with demonstrated efficacy8 within the context of a Head Start asthma educational program. We hypothesized that the group receiving ABC plus the Head Start educational program would have a significantly greater reduction in asthma morbidity compared with the group receiving the Head Start educational program alone. The primary study outcome measure was change in asthma control as measured by the Test of Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK) score.13 Secondary outcomes included use of health care services, courses of OCS, and asthma-related caretaker quality of life.

Methods

Participants

A complete copy of the trial protocol is found in Supplement 1. Participants were recruited for this randomized clinical trial from 14 Baltimore Head Start programs across 78 sites from April 1, 2011, to November 31, 2016, with final data collection ending December 31, 2017. Eligible children were aged 2 to 6 years with a physician diagnosis of asthma and had a parent or legal guardian (hereinafter referred to as a caregiver) with the ability to speak English. Physician diagnosis of asthma was verified by the child’s primary care practitioner. We originally included an inclusion criteria of active asthma symptoms but removed that during the first year. Exclusion criteria included plans to move in the next 6 months or a sibling enrolled in the study. The institutional review board of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine approved the study. The parent or legal guardian of each participating child provided written informed consent. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Procedures

An eligibility screening questionnaire was given to all enrolled students biannually by Head Start staff. The questionnaire included a checkbox to indicate declining to complete the form. When 80% of a class was screened, Head Start staff were compensated $50 for their effort; payment was provided regardless of study eligibility or enrollment. The form asked whether the Head Start student had a physician diagnosis of asthma, whether the family was interested in being contacted about the research study, and for contact information. Eligible families who gave permission were contacted by telephone to confirm eligibility and schedule the first home visit.

Assessment visits were completed at baseline and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months by a research assistant. Research assistants conducted home visits at baseline and 6 months and telephone visits at 3, 9, and 12 months. During the first home visit, the research assistant obtained written consent from the caregiver, completed a structured survey with the caregiver, reviewed medication availability, and completed an environmental home screening. Demographic data including race/ethnicity were collected from the caregiver. Families were randomized to either the ABC plus Head Start education group or the Head Start education alone group using a 1:1 block randomization scheme of groups of 10 to ensure equal group sizes. The randomization scheme was developed by a statistician using a random number generator. Randomization assignments were placed into sealed envelopes that were opened after families completed baseline surveys. Families were not blinded to their randomization, but the research assistants who completed assessments were blinded and were different from intervention staff. Caregivers were offered compensation for completing assessments ($50 for home visits and $30 for telephone visits) but not for completion of intervention activities to reflect a real-world implementation.

Measures

The primary outcome was the TRACK score to assess degree of asthma control, which has been validated for preschool children with asthma.13 TRACK contains 5 standardized questions, each of which is scored using a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 20 for a total score range of 0 to 100. Higher scores indicated better asthma control, and a TRACK score of less than 80 indicated that asthma was uncontrolled.13 Changes in TRACK scores of 10 or more points represent a clinically meaningful change in respiratory symptoms for young children.14 At the first meeting, the data safety and monitoring board recommended we change our original primary outcome of asthma symptom-free days to TRACK scores.

Caregiver reports of ED visits, hospitalizations, and courses of OCS in the previous 3 months were collected at each assessment visit. A total count of number of events for ED visits and courses of OCS were recorded at each assessment visit. Given the low frequency of hospitalizations, the total number of events was summed for an annual total 12 months before and after the date of randomization.

Caregiver health–related quality of life was measured using the Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaire. This 23-item measure assesses the problems with activity limitations, emotional functioning, and a total score experienced by parents of children with asthma,15 with higher scores indicating a better caregiver health–related quality of life.

Intervention Conditions

A key component of the trial was active engagement with Baltimore City Head Start, our community partner in this study. All Head Start programs were invited to participate in a variety of activities that ranged from staff training to parent workshops at local Head Start programs.

Yearly asthma training for all Head Start staff by the research team was offered to each Head Start program. These staff trainings provided education on asthma symptom management, medication types and administration, asthma triggers, and talking with families about asthma, including common myths. Educational sessions included didactic components, hands-on practice with inhalers, videos, and role-playing sessions. Continuing education credits were offered to all staff for their licensure through the Maryland State Department of Education.

Expert Facilitation of Asthma Activities

Asthma educators at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine served as expert facilitators for each Head Start program to provide guidance about asthma and increase awareness. Each program was encouraged to develop and implement program activities that would meet their families’ needs. These activities included parent workshops, annual health fairs, distribution of written materials, and attendance at quarterly Health Advisory Committee meetings. A complete description of the Head Start intervention and different components has been published previously.16

The ABC family intervention consisted of four 30- to 45-minute in-person, at-home asthma management educational sessions and 3 booster calls tailored to the needs of preschool children in urban home environments. Interventionists were Head Start staff or Johns Hopkins School of Medicine asthma educators who were trained to deliver asthma education to increase applicability to a real-world setting. In-person intervention content was delivered via iPads and included images and video content for low health literacy levels. Interventionists encouraged participants to write or circle information on the iPads. Educational information was tailored to the child’s asthma treatment regimen and specific triggers and caregiver concerns. The delivery of the information using technology that is tailored to the specific child’s treatment plan was a novel method to provide education on guideline-based asthma management. Content was based on National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guidelines and addressed core areas of asthma management, including symptom management, medication use, asthma action plans, acute care for exacerbations, environmental triggers, and working with health care professionals. Families participated in problem solving and goal setting with the interventionists at the end of each session to address barriers to asthma management. The intervention was designed such that most asthma education was provided within the initial visit. Intervention families also received 3 follow-up booster telephone calls after each assessment visit (3, 6, and 9 months) to check in on treatment goals and provide guidance if needed. Booster telephone calls included a review of current asthma symptoms and the current asthma treatment plan.

Sample Size Calculation

The study was powered a priori to detect an effect size of 0.79 on asthma symptoms based on the TRACK score, assuming a 2-sided α = .05, 80% power, dropout rate of 20%, intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.05, variance-covariance estimate of 0.02, and sample size of 406 participants. The effect size was selected based on a previous efficacy trial by Otsuki et al.8 Sample size calculations were conducted in SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from March 18 to August 30, 2018. Baseline characteristics were compared across the groups using unpaired, 2-tailed t tests and χ2 tests. Initial intention-to-treat analyses compared the ABC plus Head Start group with the Head Start alone group at each point for outcome measures. Generalized estimating equations were used to estimate the group population mean for each outcome over time to control for the correlation among longitudinal measures within an individual, while adjusting for baseline level of each outcome.17 For each outcome, time and intervention group were modeled as categorical fixed effects of outcomes. To determine an intervention effect at each point, the generalized estimating equation interaction of treatment by time was evaluated. For binary and continuous outcomes, negative binomial and normal distributions were specified, respectively. A logistic regression was conducted to test for group differences for cumulative hospitalization per participant between groups comparing 12 months before and after randomization. Logistic regression was used to analyze hospitalization data owing to the small overall number of hospitalizations. All models were conducted controlling for season of data collection, and asthma control as measured by the TRACK score was included as a covariate for secondary outcomes, including ED visits, courses of OCS, and hospitalizations. Three sensitivity analyses were performed for all outcomes: an as-treated analysis comparing ABC plus Head Start educational program with the Head Start educational program alone for participants who completed at least 1 home visit vs those who completed none, an as-treated analysis comparing ABC plus Head Start educational program with Head Start educational program alone for participants who completed 4 home visits vs those who did not, and a generalized estimating equation analysis that was run with all missing data censored. All analyses were conducted in Stata/SE, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC), and 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All reported regression coefficients were unstandardized.

Results

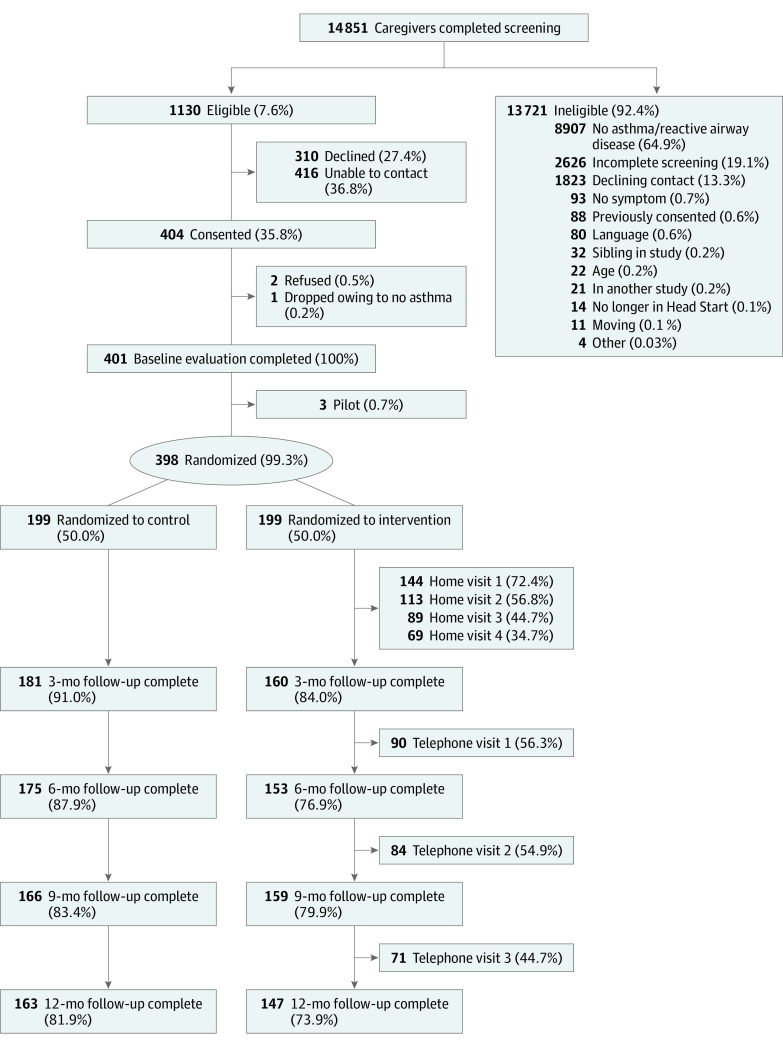

A total of 14 851 caregivers (for 90% of all children enrolled at Head Start) completed screening from April 1, 2011, to November 31, 2016. Twenty-four percent of caregivers reported that their child was diagnosed with asthma; 1130 (7.6%) were both eligible and provided permission to be contacted for the study. Overall, 404 caregivers consented, and 401 completed the baseline evaluation. Three of the 401 families were included as pilot intervention families to evaluate the intervention materials and assist with interventionist training and were not included in the final analysis. A total of 398 families were randomized to either the ABC plus Head Start educational program (n = 199) or Head Start educational program alone (n = 199) (Figure 1). Baseline demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1 (247 boys [62.1%] and 151 girls [37.9%]; mean [SD] age, 4.2 [0.7] years). Most participants were Black (379 [95.2%]) and had a family income of less than $40 000 a year (357 [89.7%]). There were no significant group differences on any demographic characteristic.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

The control group received the Head Start educational program only; the intervention group, the home-based Asthma Basic Care program plus the Head Start educational program.

Table 1. Baseline Demographic Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Study groupa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 398) | Head Start educational program alone (n = 199) | ABC plus Head Start educational program (n = 199) | |

| Child | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 4.2 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.6) |

| Black | 379 (95.2) | 190 (95.5) | 189 (95.0) |

| Female | 151 (37.9) | 75 (37.7) | 76 (38.2) |

| Caregiver | |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 34.7 (27.9-54.7) | 35.0 (28.2-54.8) | 34.1 (27.4-54.5) |

| Relationship to child | |||

| Mother | 344 (86.4) | 171 (85.9) | 173 (86.9) |

| Father | 25 (6.3) | 12 (6.0) | 13 (6.5) |

| Stepmother | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Stepfather | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| Grandmother | 11 (2.8) | 6 (3.0) | 5 (2.5) |

| Aunt | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| Legal guardian | 9 (2.3) | 4 (2.0) | 5 (2.5) |

| Other | 5 (1.3) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Educational level | |||

| Less than ninth grade | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Some high school | 75 (18.9) | 32 (16.2) | 43 (21.7) |

| High school | 137 (34.6) | 66 (33.3) | 71 (35.9) |

| Some college or trade school | 150 (37.9) | 80 (40.4) | 70 (35.4) |

| Four-year college | 32 (8.1) | 18 (9.1) | 14 (7.1) |

| Unemployed | 185 (46.7) | 93 (47.0) | 92 (46.5) |

| Annual household income | |||

| <$10 000 | 154 (39.8) | 72 (37.1) | 82 (42.5) |

| $10 000 to $20 000 | 89 (23.0) | 49 (25.3) | 40 (20.7) |

| >$20 000 to $30 000 | 73 (18.9) | 34 (17.5) | 39 (20.2) |

| >$30 000 to $40 000 | 30 (7.8) | 16 (8.2) | 14 (7.3) |

| >$40 000 | 41 (10.6) | 23 (11.9) | 18 (9.3) |

| Smoker | 75 (18.8) | 34 (17.1) | 41 (20.6) |

Abbreviations: ABC, Asthma Basic Care; IQR, interquartile range.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (percentage) of participants. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100. Two participants had missing educational level and unemployment data; 11 had missing annual household income data.

Of the 199 families randomized to the ABC plus Head Start educational intervention, 144 (72.4%) completed at least 1 home intervention session, with 69 (34.7%) completing all 4 home visits. Seventy-one families (35.8%) completed all the booster telephone calls after the 3-, 6-, and 9-month follow-up surveys. The Head Start asthma educational program was implemented at all participating Head Start programs. Asthma staff training sessions were conducted at all 14 Head Start programs during the course of the study. Investigators or research staff attended 49 health fairs and 79 health advisory committee meetings and completed 41 ABC parent workshops that provided students and caregivers with educational materials about asthma across 10 different Head Start programs.

Asthma Control

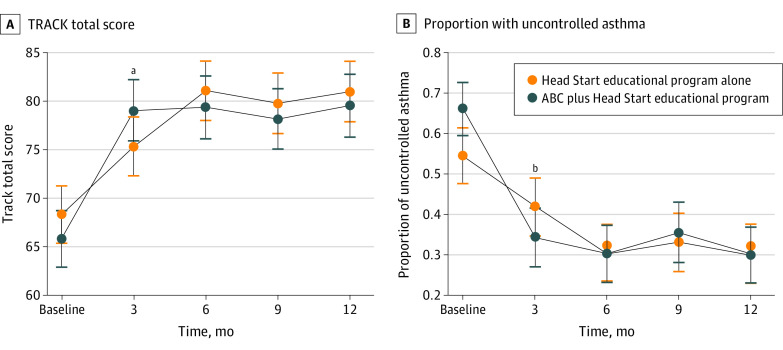

There was an overall improvement in asthma control as measured by the TRACK total score for both groups over time (β = 3.00; 95% CI, 2.47-3.54; P < .001). There also was a significant treatment by time interaction for the ABC plus Head Start group at 3 months compared with the Head Start alone group, with a score difference greater than the minimum clinically important difference (β = 6.26; 95% CI, 1.77-10.75; P < .001) (Table 2 and Figure 2A). In addition, a significantly lower proportion of children had uncontrolled asthma as measured by the TRACK total score in the ABC plus Head Start group at 3 months compared with the Head Start alone group (β = −0.81; 95% CI, −1.32 to −0.31; P = .002) (Figure 2B). There was no significant difference among groups at months 6, 9, and 12 months.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Outcome Variables.

| Variable | Study group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All | Head Start educational program alone | ABC plus Head Start educational program | |

| TRACK total score, median (IQR) | |||

| Baseline | 70 (50-85) | 75 (55-85) | 70 (50-80) |

| 3 mo | 85 (65-95) | 80 (60-90) | 85 (70-95) |

| 6 mo | 85 (75-95) | 85 (70-95) | 85 (75-95) |

| 9 mo | 85 (70-95) | 85 (75-95) | 85 (65-95) |

| 12 mo | 85 (75-95) | 85 (75-95) | 85 (70-95) |

| Uncontrolled asthma, No./total No. (%)a | |||

| Baseline | 236/398 (59.3) | 106/199 (53.3) | 130/199 (65.3) |

| 3 mo | 128/341 (37.5) | 75/181 (41.4) | 53/160 (33.1) |

| 6 mo | 99/328 (30.2) | 51/175 (29.1) | 48/153 (31.4) |

| 9 mo | 109/325 (33.5) | 53/166 (31.9) | 56/159 (35.2) |

| 12 mo | 92/310 (29.7) | 47/163 (28.8) | 45/147 (30.6) |

| PACQLQ score, median (IQR) | |||

| Baseline | 4.38 (3.77-4.85) | 4.38 (3.85-4.85) | 4.38 (3.69-4.85) |

| 3 mo | 4.54 (3.96-4.92) | 4.46 (3.92-4.85) | 4.54 (4.08-5.00) |

| 6 mo | 4.62 (4.00-5.00) | 4.54 (4.00-5.00) | 4.62 (4.00-5.00) |

| 9 mo | 4.62 (4.00-5.00) | 4.62 (4.08-5.00) | 4.62 (3.92-5.00) |

| 12 mo | 4.69 (4.23-5.00) | 4.69 (4.23-5.00) | 4.69 (4.15-5.00) |

| ED visit in last 3 mo, No./total No. (%) | |||

| Baseline | 115/398 (28.9) | 50/199 (25.1) | 65/199 (32.7) |

| 3 mo | 76/341 (22.3) | 42/181 (23.2) | 34/160 (21.3) |

| 6 mo | 60/328 (18.3) | 32/175 (18.3) | 28/153 (18.3) |

| 9 mo | 75/325 (23.1) | 38/166 (22.9) | 37/159 (23.3) |

| 12 mo | 66/310 (21.3) | 35/163 (21.5) | 31/147 (21.1) |

| Courses of OCS in the last 3 mo, No./total No. (%) | |||

| Baseline | 101/398 (25.4) | 50/199 (25.1) | 51/199 (25.6) |

| 3 mo | 79/341 (23.2) | 45/181 (24.9) | 34/160 (21.3) |

| 6 mo | 62/328 (18.9) | 34/175 (19.4) | 28/153 (18.3) |

| 9 mo | 64/325 (19.7) | 34/166 (20.5) | 30/159 (18.9) |

| 12 mo | 56/310 (18.1) | 28/163 (17.2) | 28/147 (19.0) |

Abbreviations: ABC, Asthma Basic Care; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range; OCS, oral corticosteroids; PACQLQ, Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaire; TRACK, Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids.

Uncontrolled asthma was calculated using a TRACK score of 80 or greater.

Figure 2. Asthma Control by Group Over Time.

Data were calculated using a generalized estimating equation model adjusted for season. B, Uncontrolled asthma was calculated using a Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK) score of at least 80. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. ABC indicates Asthma Basic Care.

aP < .001.

bP = .002.

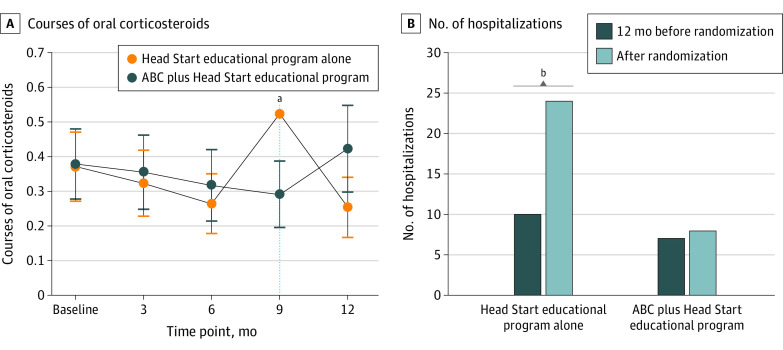

Secondary Outcomes: Use of Health Care Resources

There was no overall change in ED visits or courses of OCS over time for either group. There was a significant treatment by time interaction for the ABC plus Head Start group at 9 months compared with the Head Start alone group on number of OCS courses (β = −0.61; 95% CI, −1.13 to −0.09; P = .02), but there was no treatment by time difference in ED visits. Participants in the ABC plus Head Start group were significantly less likely to have a hospitalization during the 12-month follow-up period (odds ratio, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.21- 0.61; P < .001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Asthma Exacerbations by Group Over Time.

A, Data were calculated using a generalized estimating equation model adjusted for season. B, Data were calculated using logistic regression model adjusted for season and Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids score. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. ABC indicates Asthma Basic Care.

aP = .002.

bP < .001.

Asthma-Related Quality of Life

There was a significant improvement in asthma-related quality of life at 12 months for both groups (β = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.19-0.38; P < .001), which means that both groups experienced improvements in their quality of life at the 12-month follow-up. However, there were no significant treatment by time interactions, indicating no intervention effect on this outcome.

Each of our 3 sensitivity analyses showed no difference in outcomes from the primary results presented. Therefore, we only provided the results from the intention-to-treat analyses.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a multilevel asthma intervention implemented in both the home and Head Start settings for low-income minority children. The ABC plus Head Start educational program had a modest effect in improving asthma control, reducing courses of OCS, and reducing hospitalizations compared with a Head Start educational program alone. Although both groups’ asthma control improved significantly in the 12 months after randomization, the ABC plus Head Start group had a greater reduction in proportion of children with uncontrolled asthma over time. Notably, within this intervention, most of the asthma educational information was delivered within the first home visit, based on results of our earlier research.8

The ABC plus Head Start asthma educational program and its delivery approach using a community partner was an effective strategy for targeting a population disproportionately affected by health disparities. Low-income minority children are at greater risk for poor asthma outcomes and significant health disparities. For interventions to reduce disparities and improve outcomes, they must be implemented and evaluated in settings that serve at-risk populations. Partnering with community organizations such as Head Start, whose mission aligns to improve respiratory health, can be critical for implementing and evaluating interventions designed to reduce health disparities. Furthermore, Head Start already has an existing infrastructure of regular home visits that would provide opportunity for implementing and sustaining an effective home-based asthma educational program.

The family educational program (ABC) that was included in this study was previously shown to be efficacious in reducing asthma symptoms and ED visits for children with asthma aged 2 to 12 years recruited from the ED.8 The ABC plus Head Start intervention evaluated in this study was conducted in line with prior research6,18 that has shown that successful interventions to reduce health disparities benefit from multilevel approaches, culture- and literacy-appropriate materials, and tailoring of material to meet the needs of the community. This intervention was novel in its use of technology (iPads) to deliver guideline-based educational material within home visits.19

This study included 2 active interventions, one provided only in the school setting and another provided at both home and school. A multilevel school and home intervention can reinforce and support good asthma management, because preschool children split their day between school and home settings and may require asthma care at either location. Providing an intervention in the home setting allows for an environmental home screening to be performed along with provision of education regarding environmental triggers. At-home interventions also allow for an assessment of asthma medication availability within the home, which is frequently inadequate.20 Furthermore, the synergy of providing an intervention in 2 settings may increase overall awareness of asthma for families, allow reinforcement of education, and provide multiple opportunities to provide education and support. Previous research7 has found that interventions provided across multiple levels of the social ecological framework, such as school and home, are more likely to have an impact on health.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. The primary outcome was changed from symptom-free days to asthma control at the recommendation of the data safety and monitoring board. Use of health care resources for asthma outcomes was collected via caregiver report and not verified using medical records, possibly leading to bias. Previous research21 has shown that caregivers are able to accurately recall use of urgent health care. Our study sample were all low income and predominately African American. Although these demographics may limit our generalizability, they can be seen as a strength of the study because we identified an effective intervention for a vulnerable population. However, selection bias for more engaged caregivers who chose to participate in this study and for caregivers who had the resources to complete home and telephone visits may have occurred. In addition, we relied exclusively on physician-confirmed diagnosis of asthma, because young children are not able to complete spirometry.22

Conclusions

There are known disparities in pediatric asthma, with low-income and minority children at greatest risk for uncontrolled asthma, increased rates of asthma exacerbations, and higher rates of use of urgent health care services. Identifying effective interventions that can be implemented in settings that serve these populations and have a broad influence on population health is critical. This study demonstrated that a home-based family educational program, ABC, combined with a Head Start educational program was effective in improving asthma control and reducing OCS course and hospitalizations. Research is needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of this intervention as well as engagement with community organizations to develop policies and procedures for broad implementation.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Zahran HS, Bailey CM, Damon SA, Garbe PL, Breysse PN. Vital signs: asthma in children—United States, 2001-2016. Published February 9. 2018. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6705e1.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Simon AE, Schoendorf KC. Trends in racial disparities for asthma outcomes among children 0 to 17 years, 2001-2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(3):547-553.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson K, Theberge S; National Center for Children in Poverty. Reducing disparities beginning in early childhood: Short Take No. 4. Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health. Published July 2007. Accessed March 27, 2020. http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_744.html [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd M, Lasserson TJ, McKean MC, Gibson PG, Ducharme FM, Haby M. Interventions for educating children who are at risk of asthma-related emergency department attendance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD001290. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001290.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJ, Bailey CM, et al. National surveillance of asthma: United States, 2001-2010. Vital Health Stat 3. 2012;(35):1-58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canino G, McQuaid EL, Rand CS. Addressing asthma health disparities: a multilevel challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6):1209-1217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark NM, Mitchell HE, Rand CS. Effectiveness of educational and behavioral asthma interventions. Pediatrics. 2009;123(suppl 3):S185-S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otsuki M, Eakin MN, Rand CS, et al. Adherence feedback to improve asthma outcomes among inner-city children: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1513-1521. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Environmental Protection Agency. Coordinated Federal Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Asthma Disparities. President's Task Force on Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks to Children; 2012:1-19. Updated July 3, 2018. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://www.epa.gov/asthma/coordinated-federal-action-plan-reduce-racial-and-ethnic-asthma-disparities [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark NM. Community-based approaches to controlling childhood asthma. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:193-208. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Administration for Children and Families ; US Department of Health and Human Services; Office of Head Start. The Head Start parent, family, and community engagement framework: promoting family engagement and school readiness, from prenatal to age 8. Updated April 27, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/school-readiness/article/head-start-parent-family-community-engagement-framework

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services; Administration for Children and Families; Office of Head Start . Head Start early learning outcomes framework. 2015:1-75. Updated July 27, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/school-readiness/article/head-start-early-learning-outcomes-framework [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy KR, Zeiger RS, Kosinski M, et al. Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK): a caregiver-completed questionnaire for preschool-aged children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(4):833-839.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeiger RS, Mellon M, Chipps B, et al. Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK): clinically meaningful changes in score. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(5):983-988. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(1):27-34. doi: 10.1007/BF00435966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruvalcaba E, Chung SE, Rand C, Riekert KA, Eakin M. Evaluating the implementation of a multicomponent asthma education program for Head Start staff. J Asthma. 2019;56(2):218-226. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2018.1443467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121-130. doi: 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(6):477-486. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welsh EJ, Hasan M, Li P. Home-based educational interventions for children with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD008469. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008469.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callaghan-Koru JA, Riekert KA, Ruvalcaba E, Rand CS, Eakin MN. Home medication readiness for preschool children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20180829. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tisnado DM, Adams JL, Liu H, et al. What is the concordance between the medical record and patient self-report as data sources for ambulatory care? Med Care. 2006;44(2):132-140. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196952.15921.bf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cave AJ, Atkinson LL. Asthma in preschool children: a review of the diagnostic challenges. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(4):538-548. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.04.130276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement